This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Wilmington (Lenape: Paxahakink / Pakehakink)[4] is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Delaware. The city was built on the site of Fort Christina, the first Swedish settlement in North America. It lies at the confluence of the Christina River and Brandywine Creek, near where the Christina flows into the Delaware River. It is the county seat of New Castle County and one of the major cities in the Delaware Valley metropolitan area (synonymous with the Philadelphia metropolitan area). Wilmington was named by Proprietor Thomas Penn after his friend Spencer Compton, Earl of Wilmington, who was prime minister during the reign of George II of Great Britain.

Wilmington, Delaware

Paxahakink / Pakehakink (Unami) | |

|---|---|

Downtown Wilmington and the Christina River | |

| Etymology: Named after Spencer Compton, Earl of Wilmington | |

| Nickname(s): Corporate Capital of the World, Chemical Capital of the World | |

| Motto: In the middle of it all[1] | |

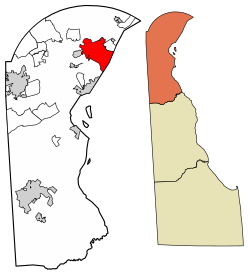

Location within New Castle County | |

| Coordinates: 39°44′45″N 75°32′48″W / 39.74583°N 75.54667°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Delaware |

| County | New Castle |

| Founded at The Rocks, Swedes' Landing, Fort Christina, Kristinehamn settlement | March 1638 |

| Incorporated as Willingtown | 1731 |

| Borough Charter as Wilmington | 1739 |

| City Charter | March 7, 1832 |

| Named for | Spencer Compton, 1st Earl of Wilmington |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-mayor |

| • Mayor | Mike Purzycki (D) |

| Area | |

• City | 17.19 sq mi (44.52 km2) |

| • Land | 10.89 sq mi (28.22 km2) |

| • Water | 6.29 sq mi (16.30 km2) |

| • Urban - Northern NCCo.DE | 213.35 sq mi (552.58 km2) |

| • Metro - Wilmington/Newark Statistical Division, DE-MD-NJ | 1,103.86 sq mi (2,859 km2) |

| Elevation | 92 ft (28 m) |

| Highest elevation - Mount Salem Hill, Rockford Park | 330 ft (100 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 70,898 (within city limits) |

| • Density | 6,510.38/sq mi (2,512.48/km2) |

| • Urban - Northern NCCo.DE | 484,926 (US: 87th) |

| • Urban density | 2,272.91/sq mi (877.57/km2) |

| • Metro | 723,993 (US: 82nd)(Wilmington Metropolitan Division DE-MD-NJ Delaware statistical areas |

| • Metro density | 655.87/sq mi (253.23/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 19801-19810, 19850, 19880, 19884-19886, 19890-19899 |

| Area code | 302 |

| FIPS code | 10-77580 |

| GNIS feature ID | 214862[3] |

| Airport | Wilmington Airport |

| Major highways | |

| Commuter rail | |

| Website | wilmingtonde.gov |

As of the 2020 census, the city's population was 70,898.[5] Wilmington is part of the Delaware Valley metropolitan statistical area (which also includes Philadelphia, Reading, Camden, and other urban areas), which had a 2020 core metropolitan statistical area population of 6,228,601, representing the seventh largest metropolitan region in the nation, and a combined statistical area population of 7.366 million.[6]

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

Wilmington is built on the site of Fort Christina and the settlement Kristinehamn,[7] the first Swedish settlement in North America. The modern city also encompasses other Swedish settlements, such as Timmerön / Timber Island (along Brandywine Creek), Sidoland (South Wellington), Strandviken (along the Delaware River near Simonds Garden) and Översidolandet (along the Christina River, near Woodcrest and Ashley Heights).

The area now known as Wilmington was settled by the Lenape (or Delaware Indian) band led by Sachem (Chief) Mattahorn just before Henry Hudson sailed up the Len-api Hanna ("People Like Me River", present Delaware River) in 1609. The area was called "Maax-waas Unk" or "Bear Place" after the Maax-waas Hanna (Bear River) that flowed by (present Christina River). It was called the Bear River because it flowed west to the "Bear People", who are now known as the People of Conestoga or the Susquehannocks.

The Dutch heard and spelled the river and the place as Minguannan. When settlers and traders from the Swedish South Company under Peter Minuit arrived in March 1638 on the Fogel Grip and Kalmar Nyckel, they purchased Maax-waas Unk from Chief Mattahorn and built Fort Christina at the mouth of the Maax-waas Hanna (which the Swedes renamed the Christina River after Queen Christina of Sweden). The area was also known as "The Rocks", and is located near the foot of present-day Seventh Street. Fort Christina served as the headquarters for the colony of New Sweden which consisted of, for the most part, the lower Delaware River region (parts of present-day Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey), but few colonists settled there.[8][9] Dr. Timothy Stidham (Swedish:Timen Lulofsson Stiddem) was a prominent citizen and doctor in Wilmington. He was born in 1610, probably in Hammel, Denmark, and raised in Gothenburg, Sweden. He arrived in New Sweden in 1654 and is recorded as the first physician in Delaware.[10][11]

The most important Swedish governor was Colonel Johan Printz, who ruled the colony under Swedish law from 1643 to 1653. He was succeeded by Johan Rising, who upon his arrival in 1654, seized the Dutch post Fort Casimir, located at the site of the present town of New Castle, which was built by the Dutch in 1651. Rising governed New Sweden until the autumn of 1655, when a Dutch fleet under the command of Peter Stuyvesant subjugated the Swedish forts and established the authority of the Colony of New Netherland throughout the area formerly controlled by the Swedes. This marked the end of Swedish rule in North America.

Beginning in 1664, British colonization began; after a series of wars between the Dutch and English, the area stabilized under British rule, with strong influences from the Quaker communities under the auspices of Proprietor William Penn. A borough charter was granted in 1739 by King George II, which changed the name of the settlement from Willington, after Thomas Willing (the first developer of the land, who organized the area in a grid pattern similar to that of its northern neighbor Philadelphia),[12][13][14] to Wilmington, presumably after the British Prime Minister Spencer Compton, Earl of Wilmington, who took his title from Wilmington, East Sussex, in southern England.

Although during the American Revolutionary War only one small battle was fought in Delaware, British troops occupied Wilmington shortly after the nearby Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. The British remained in the town until they vacated Philadelphia in 1778.

In 1800, Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, a French Huguenot, emigrated to the United States. Knowledgeable in the manufacture of gunpowder, by 1802 DuPont had begun making the explosive in a mill on the Brandywine River north of Brandywine Village and just outside the town of Wilmington.[15] The DuPont company became a major supplier to the U.S. military.[16] Located on the banks of the Brandywine River, the village was eventually annexed by Wilmington city.

The greatest growth in the city occurred during the Civil War. Delaware, though officially remaining a member of the Union, was a border state and divided in its support of both the Confederate and the Union causes. The war created enormous demand for goods and materials supplied by Wilmington including ships, railroad cars, gunpowder, shoes, and other war-related goods.

By 1868, Wilmington was producing more iron ships than the rest of the country combined[citation needed] and it rated first in the production of gunpowder and second in carriages and leather. Due to the prosperity Wilmington enjoyed during the war, city merchants and manufacturers expanded Wilmington's residential boundaries westward in the form of large homes along tree-lined streets. This movement was spurred by the first horsecar line, which was initiated in 1864 along Delaware Avenue.

The late 19th century saw the development of the city's first comprehensive park system. William Poole Bancroft, a successful Wilmington businessman influenced by the work of Frederick Law Olmsted, led the effort to establish open parkland in Wilmington. Rockford Park and Brandywine Park were created due to Bancroft's efforts.

Both World Wars stimulated the city's industries. Industries vital to the war effort – shipyards, steel foundries, machinery, and chemical producers – operated around the clock. Other industries produced such goods as automobiles, leather products, and clothing. In desperate need of workers more and more minorities moved to the north and settled in places like Wilmington. This led to tensions that occasionally boiled over like the Wilmington, Delaware race riot of 1919.

The post-war prosperity again pushed residential development further out of the city. In the 1950s, more people began living in the suburbs of North Wilmington and commuting into the city to work. This was made possible by extensive upgrades to area roads and highways and through the construction of Interstate 95, which cut through several of Wilmington's neighborhoods and accelerated the city's population decline. Urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s cleared entire blocks of housing in the Center City and East Side areas.

The Wilmington riot of 1968, a few days after the April 4 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., became national news. On April 9, Governor Charles L. Terry, Jr. deployed the National Guard and the Delaware State Police to the city at the request of Mayor John Babiarz. Babiarz asked Terry to withdraw the National Guard the following week, but the governor kept them in the city until his term ended in January 1969. This is reportedly the longest occupation of an American city by state forces in the nation's history.[17]

In the 1980s, job growth and office construction were spurred by the arrival of national banks and financial institutions in the wake of the 1981 Financial Center Development Act, which liberalized the laws governing banks operating within the state, and similar laws in 1986. Today, many national and international banks, including Bank of America, Capital One, Chase, and Barclays, have operations in the city, typically credit card operations.

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 17.0 square miles (44 km2), of which 10.9 square miles (28 km2) is land and 6.2 square miles (16 km2) is water. The total area is 36.25% water.

The city sits at the confluence of the Christina and Delaware rivers, approximately 33 miles (53 km) southwest of Philadelphia. Wilmington Train Station, one of the southernmost stops on Philadelphia's SEPTA rail transportation system, is also served by Northeast Corridor Amtrak passenger trains. Wilmington is served by I-95 and I-495 within city limits. In addition, the twin-span Delaware Memorial Bridge, a few miles south of the city, provides direct highway access between Delaware and New Jersey, carrying the I-295 eastern bypass route around Wilmington and Philadelphia, as well as US 40, which continues eastward to Atlantic City, New Jersey.

These transportation links and geographic proximity give Wilmington some of the characteristics of a satellite city to Philadelphia, but Wilmington's long history as Delaware's principal city, its urban core, and its independent value as a business destination makes it more properly considered a small but independent city in the Philadelphia metropolitan area.

Wilmington lies along the Fall Line geological transition from the Mid-Atlantic Piedmont Plateau to the Atlantic Coastal Plain. East of Market Street, and along both sides of the Christina River, the Coastal Plain land is flat, low-lying, and in places marshy. The Delaware River here is an estuary at sea level (with twice-daily high and low tides), providing sea-level access for ocean-going ships.

On the western side of Market Street, the Piedmont topography is rocky and hilly, rising to a point that marks the watershed between the Brandywine River and the Christina River. This watershed line runs along Delaware Avenue westward from 10th Street and Market Street.

These contrasting topography and soil conditions affected the industrial and residential development patterns within the city. The hilly west side was more attractive for the original residential areas, offering springs and sites for mills, better air quality, and fewer mosquitoes.

Surrounding municipalities

editClimate

editWilmington has a warm temperate climate or humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with hot and humid summers, cool to cold winters, and precipitation evenly spread throughout the year. In July, the daily average is 76.8 °F (24.9 °C), with an average 21 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs annually. Summer thunderstorms are common in the hottest months. The January daily average is 32.4 °F (0.2 °C), although temperatures may occasionally reach 10 °F (−12 °C) or 55 °F (13 °C) as fronts move toward and past the area. Snowfall is light to moderate, and variable, with some winters bringing very little of it and others witnessing several major snowstorms; the average seasonal total is 20.2 inches (51 cm). Extremes in temperature have ranged from −15 °F (−26 °C) on February 9, 1934, up to 107 °F (42 °C) on August 7, 1918, though both 100 °F (38 °C)+ and 0 °F (−18 °C) readings are uncommon; the last occurrence of each was July 18, 2012 and February 5, 1996, respectively.

| Climate data for Wilmington, Delaware (New Castle County Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1894–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

97 (36) |

98 (37) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

107 (42) |

100 (38) |

98 (37) |

85 (29) |

75 (24) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 63.1 (17.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

73.8 (23.2) |

83.3 (28.5) |

89.1 (31.7) |

93.5 (34.2) |

95.8 (35.4) |

93.8 (34.3) |

89.7 (32.1) |

82.6 (28.1) |

72.3 (22.4) |

64.2 (17.9) |

96.9 (36.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 41.4 (5.2) |

44.1 (6.7) |

52.5 (11.4) |

64.2 (17.9) |

73.5 (23.1) |

82.2 (27.9) |

86.8 (30.4) |

84.9 (29.4) |

78.5 (25.8) |

67.0 (19.4) |

55.9 (13.3) |

46.0 (7.8) |

64.8 (18.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.5 (0.8) |

35.5 (1.9) |

43.2 (6.2) |

53.9 (12.2) |

63.5 (17.5) |

72.6 (22.6) |

77.6 (25.3) |

75.8 (24.3) |

68.9 (20.5) |

57.2 (14.0) |

46.6 (8.1) |

38.2 (3.4) |

55.5 (13.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25.6 (−3.6) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

33.9 (1.1) |

43.5 (6.4) |

53.4 (11.9) |

63.0 (17.2) |

68.3 (20.2) |

66.6 (19.2) |

59.3 (15.2) |

47.3 (8.5) |

37.4 (3.0) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

46.3 (7.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.7 (−12.4) |

12.0 (−11.1) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

39.2 (4.0) |

49.9 (9.9) |

58.3 (14.6) |

56.0 (13.3) |

45.1 (7.3) |

33.4 (0.8) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

16.4 (−8.7) |

7.4 (−13.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−15 (−26) |

2 (−17) |

11 (−12) |

30 (−1) |

40 (4) |

48 (9) |

43 (6) |

32 (0) |

23 (−5) |

11 (−12) |

−7 (−22) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.23 (82) |

2.83 (72) |

4.16 (106) |

3.51 (89) |

3.57 (91) |

4.67 (119) |

4.41 (112) |

3.98 (101) |

4.38 (111) |

3.68 (93) |

3.06 (78) |

3.85 (98) |

45.33 (1,151) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.1 (15) |

7.8 (20) |

3.1 (7.9) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

2.9 (7.4) |

20.2 (51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.8 | 10.0 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 11.7 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 10.6 | 121.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.5 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 10.7 |

| Source: NOAA[18][19] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 5,268 | — | |

| 1830 | 6,628 | 25.8% | |

| 1840 | 8,367 | 26.2% | |

| 1850 | 13,979 | 67.1% | |

| 1860 | 21,258 | 52.1% | |

| 1870 | 30,841 | 45.1% | |

| 1880 | 42,478 | 37.7% | |

| 1890 | 61,431 | 44.6% | |

| 1900 | 76,508 | 24.5% | |

| 1910 | 87,411 | 14.3% | |

| 1920 | 110,168 | 26.0% | |

| 1930 | 106,597 | −3.2% | |

| 1940 | 112,504 | 5.5% | |

| 1950 | 110,356 | −1.9% | |

| 1960 | 95,827 | −13.2% | |

| 1970 | 80,386 | −16.1% | |

| 1980 | 70,195 | −12.7% | |

| 1990 | 71,529 | 1.9% | |

| 2000 | 72,664 | 1.6% | |

| 2010 | 70,851 | −2.5% | |

| 2020 | 70,898 | 0.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 1980[21] | Pop 1990[22] | Pop 2000[23] | Pop 2010[24] | Pop 2020[25] | % 1980 | % 1990 | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 30,952 | 28,987 | 23,352 | 19,770 | 18,892 | 44.09% | 40.52% | 32.14% | 27.90% | 26.65% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 35,665 | 36,911 | 40,545 | 40,170 | 38,627 | 50.81% | 51.60% | 55.80% | 56.70% | 54.48% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 68 | 141 | 133 | 158 | 116 | 0.10% | 0.20% | 0.18% | 0.22% | 0.16% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 132 | 307 | 468 | 648 | 907 | 0.19% | 0.43% | 0.64% | 0.91% | 1.28% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | N/A | N/A | 14 | 4 | 21 | N/A | N/A | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.03% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 71 | 111 | 110 | 137 | 342 | 0.10% | 0.16% | 0.15% | 0.19% | 0.48% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | N/A | N/A | 894 | 1,176 | 2,570 | N/A | N/A | 1.23% | 1.66% | 3.62% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 3,307 | 5,072 | 7,148 | 8,788 | 9,423 | 4.71% | 7.09% | 9.84% | 12.40% | 13.29% |

| Total | 70,195 | 71,529 | 72,664 | 70,851 | 70,898 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 70,898 people, 31,754 households, and 13,572 families residing in the city.

2010 census

editAs of the census of 2010, there were 70,851 people, 28,615 households, and 15,398 families residing in the city. The population density was 6,497.6 inhabitants per square mile (2,508.7/km2). There were 32,820 housing units at an average density of 3,009.9 per square mile (1,162.1/km2) and with an occupancy rate of 87.2%. The racial makeup of the city was 58.0% African American, 32.6% White, 0.4% Native American, 1.0% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander, 5.4% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. 12.4% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. Non-Hispanic Whites were 27.9% of the population in 2010,[26] compared to 40.5% in 1990.[27] As of the census of 2000, the largest ethnicities included: Irish (8.7%), Italian (5.7%), German (5.2%), English (4.4%), and Polish (3.6%).[28]

There were 28,615 households, out of which 25.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 23.5% were married couples living together, 24.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 46.2% were non-families. 38.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.36 and the average family size was 3.18.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 24.4% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 24.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.4 males.

According to ACS one-year estimates for 2010, the median income for a household in the city was $32,884, and the median income for a family was $37,352. Males working full-time had a median income of $41,878 versus $36,587 for females working full-time. The per capita income for the city was $24,861. 27.6% of the population and 24.9% of families were below the poverty line. 45.7% of those under the age of 18 and 16.5% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[29]

Government

editThe Wilmington City Council consists of thirteen members. The council consists of eight members who are elected from geographic districts, four elected at-large and the City Council President. The Council President is elected by the entire city. The Mayor of Wilmington is also elected by the entire city.

The current mayor of Wilmington is Mike Purzycki (D).[30] The current city council members are listed in the table below.[31]

| District | Councilperson | Party | - |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Ernest “Trippi” Congo II | Democratic | 2017 |

| Treasurer | DaWayne Sims | Democratic | 2020 |

| 1 | Linda Gray | Democratic | 2020 |

| 2 | Shané Darby | Democratic | 2020 |

| 3 | Zanthia Oliver | Democratic | 2017 |

| 4 | Michelle Harlee | Democratic | 2017 |

| 5 | Bregetta Fields | Democratic | 2020 |

| 6 | Yolanda McCoy | Democratic | 2017 |

| 7 | Chris Johnson | Democratic | 2020 |

| 8 | Nathan Field | Democratic | 2020 |

| At-Large | Maria Cabrera | Democratic | 2020 |

| Rysheema Dixon | Democratic | 2020 | |

| James Spadola | Republican | 2020 | |

| Loretta Walsh | Democratic | 2017 |

The Delaware Department of Correction Howard R. Young Correctional Institution, renamed from Multi-Purpose Criminal Justice Facility in 2004 and housing both pretrial and posttrial male prisoners, is located in Wilmington. The prison is often referred to as the "Gander Hill Prison" after the neighborhood it is located in. The prison opened in 1982.[32]

Many Wilmington City workers belong to one of several Locals of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees union.[33]

Neighborhoods

editThe city of Wilmington is made up of the following neighborhoods:[34]

North of the Brandywine River

edit- Baynard Village

- Brandywine Hills – This neighborhood of approximately 225 homes in northern Wilmington was started in the 1930s. The streets in the neighborhood are named after famous American and English authors, including Byron, Emerson, Hawthorne and Milton. It is bounded by Lea Boulevard, Rockwood Road, Miller Road, and Market Street[35]

- Brandywine Village[36]

- Eastlawn

- Eastlake

- Gander Hill - site of Howard R. Young Correctional Institution

- Harlan

- Ninth Ward – Originally a post-Civil War political creation, the city's Ninth Ward has long been an area with owner-occupied residences. The Ninth Ward was integrated as a result of population shifts in the 1960s and remains a stable, working-class neighborhood.

- Prices Run - west of Northern Boulevard

- Riverside–11th Street Bridge – in the northeastern part of the city between the Northeast Corridor and Northern Boulevard.

- Triangle – a group of homes built in the 1920s whose corresponding streets along I-95 and Baynard Boulevard and 18th Street and Concord Avenue loosely form a triangle.[37] It is bounded by W 18th St, Baynard Boulevard, Concord Ave, and Broom St.

East of I-95

edit- Center City (Downtown)

- East Side

- Justison Landing

- LOMA

- Midtown Brandywine – Located on the banks of the Brandywine River, Midtown Brandywine is bordered by North Washington Street, East 11th Street, North French Street and South Park Drive. Homes in the neighborhood were first established in the late 1800s as the Brandywine River became home to several mills and trading posts. Midtown Brandywine's boundaries include the Brandywine Park, Fletcher Brown Park, the Hercules building, a neighborhood adopted pocket park, and several notable restaurants and eateries. The neighborhood is also home to "The Little Church", previously known as The Old Presbyterian Church. Originally built on Market Street between 9th and 10th streets, the gambrel-roofed church was relocated to its current site on South Park Drive in 1917 and has since become synonymous with Midtown Brandywine.[38]

- Quaker Hill[39] – From a country hilltop in the 19th century to rows of city homes today, Quaker Hill (which surrounds the historical Quaker Friends Meeting House) has watched its neighborhood become much more modernized over the last three centuries. This city district was founded by Quakers William Shipley and Thomas West in the early 18th century. The nearby Meeting House keeps Quaker Hill closely tied to its rich history. The cemetery of the Wilmington Friends House is the burial site of the abolitionist Thomas Garrett and John Dickinson, signer of the U.S. Constitution.[40]

- Riverfront[41] – Formerly a hub for manufacturing and the city's shipbuilding industry, which began to see a rapid series of state-sponsored urban renewal and gentrification projects beginning in the late 1990s. The neighborhood is currently home to landmarks such as the Wilmington Blue Rocks' Baseball Stadium and the Shipyard Shops.

- Southbridge

- Trinity Vicinity – This neighborhood is located in the center of Wilmington, next to the Trinity Church and Interstate 95. A collection of row homes and detached houses, many of which were originally built in the late 19th century. The revitalization of the neighborhood was aided by the Urban Homesteading Act in the 1970s. The neighborhood was designated as a historic district in the 1990s.[42]

- Upper East Side (East Brandywine)

- West Center City

- 11th St. Bridge[43]

West of I-95

edit- Bayard Square

- Browntown – areas in the city that were originally populated by Polish immigrants. Today, the Polish community maintains a strong presence, while other ethnicities have moved in the neighborhood's borders.[44]

- Canby Park – About 1930 the Wilmington City Council renamed Southwest Park as Canby Park in honor of Henry and William Marriott Canby.[45] Canby Park Estates is on one side of the park.

- Cool Spring & Tilton Park – bounded loosely by Pennsylvania Avenue on the north, West 7th Street on the south, North Jackson Street on the east and North Rodney Street on the west. The neighborhood is home to two Catholic schools, Ursuline Academy[46] and Padua Academy.[47] The neighborhood is also the location of the private University & Whist Club and the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church, which hosts an annual Greek cultural festival.[48]

- Delaware Avenue

- The Flats – The Flats was founded by businessman William Bancroft who developed the neighborhood in 1901 under the Woodlawn Company, now known as the Woodlawn Trustees, with the intention of creating affordable homes for working class residents of Wilmington. The predominantly minority community is currently in the process of gaining authorization for a $100 million revitalization to be performed in seven phases over 12 years.[49]

- Forty Acres – This historically Irish neighborhood, rural until the mid-19th century, developed from the farmland of Joshua T. Heald. One of the city's first suburbs, the neighborhood is centered on the St. Ann's Roman Catholic Church. The name Forty Acres is taken from the fertility of the farmland. One acre of the land was said to be worth 40 acres (160,000 m2) one might find someplace else. The neighborhood exists northeast of Delaware Avenue, southwest of Riddle Avenue, east of Union Street and west of DuPont Street, with Lovering Avenue as its eastern boundary.[50]

- Greenhill

- Happy Valley – a small collection of late 19th-century row houses on the southeastern slope to Brandywine Park, between Adams Street, Van Buren Street (I-95), Wawaset Street and Gilpin Avenue. This neighborhood also includes a significant number of more modern townhouses (1970's) designed by architect Richard Chalfant.

- Hedgeville

- The Highlands – located between Pennsylvania Avenue and Delaware Avenue, the Highlands neighborhood, centered on 18th Street southeast of Rockford Park, was developed by Joshua Heald in the 19th century for affluent, middle-class residents. It contains detached and semi-detached houses of exuberant architectural detailing, representing numerous popular styles of the time.

- Hilltop – This area located along 4th Street and roughly bordered by Lancaster Avenue, Jackson Street, Clayton Street has remained one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the city since the late 19th century. Today, this area is home to one of the city's fastest growing segments – the Hispanic community.[51] Historically, Westside/Hilltop was one of the two of city's most crime and drug plagued neighborhoods based on the number of service calls for police. In the Westside/Hilltop area, drug related calls was 285 in 1989 and 808 in 1990. "This increase in reported drug activity coincides with similar increases in other cities which were related to the growth of the crack cocaine trade."[52]

- Little Italy – this neighborhood consists of the area around Union Street and Lincoln streets, between Pennsylvania Avenue and Lancaster Avenue. Anchored by the immigration waves of the late 19th century and early 20th century, Little Italy has retained its roots, even as neighborhood remodeling projects update the scenery. A central feature of the neighborhood is the St. Anthony of Padua Roman Catholic Church. The neighborhood hosts an annual Italian Festival in the summertime.[53]

- St. Elizabeth Area – The St. Elizabeth area is anchored by the St. Elizabeth Parish at 809 S. Broom St., considered the heart of the Catholic community. This historic church, built on the grounds of the Banning Estate, dates back to 1908.

- Trolley Square – settled in the 1860s after the city's trolley line had extended into farmland once owned by the Shallcross and Lovering families. The city's former trolley depot and bus barn was located on the spot where the Trolley Square shopping complex now sits. The neighborhood lies between Harrison Street, Pennsylvania Avenue, Lovering Avenue and the CSX Transportation railroad track.[55] The depot and other buildings were demolished in 1974 and the mall opened in 1978.[56]

- Wawaset

- Wawaset Heights

- Wawaset Park – The neighborhood was constructed by the Dupont Company in 1918 to provide a residential community for their employees. Baltimore architect Edward L. Palmer, Jr. was chosen to design the community, which was to have a mix of single family homes and smaller attached Prior to the development of houses. The neighborhood was constructed on a 50-acre (200,000 m2) plot. Prior to its construction, the tract of land had been used as a horse racing track and a fairground. Wawaset Park was placed on the Register of Historic Places in 1986. The neighborhood is bounded by Pennsylvania Avenue, West 7th Street, Woodlawn Avenue and Greenhill Avenue.[57]

- West Hill

- Westmoreland – detached housing developed in the 1950s, as part of the suburban movement that followed the end of World War II. Its location is adjacent to the original Wilmington Country Club, bounded by Ogle Avenue, Dupont Road, the Wilmington High School property and the Ed "Porky" Oliver Golf Course.

- Union Park Gardens[58]

Historic districts and Conservation District

editThe City of Wilmington designates nine areas as historic districts and one area as a conservation district. The historic districts are the Baynard Boulevard, Kentmere Parkway, Rockford Park, Cool Spring/Tilton Park, the tri-part sections of the Eastside, St. Marys and Old Swedes Church, Quaker Hill, Delaware Avenue, Trinity Vicinity, and Upper/Lower Market Street.[59] The conservation district is Forty Acres.

Gallery

edit-

The Brandywine Academy building

-

Friends Meeting House in Quaker Hill

-

Cathedral of Saint Peter in Quaker Hill

-

Old Swedes Church depicted on the 1937 Delaware Tercentenary half dollar coin

Public safety

editCrime

edit| Wilmington | |

|---|---|

| Crime rates* (2019) | |

| Violent crimes | |

| Homicide | 24 |

| Rape | 19 |

| Robbery | 326 |

| Aggravated assault | 689 |

| Total violent crime | 1,058 |

| Property crimes | |

| Burglary | 569 |

| Larceny-theft | 2,121 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 460 |

| Arson | 2 |

| Total property crime | 3,150 |

Notes *Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. 2019 population: 70,624 Source: 2020 FBI UCR Data | |

Wilmington has recently overcome its safety woes and is "safer now than it's ever been" with crime at its lowest rate in recent history.[60] Prior to 2018, Wilmington was consistently ranked among the most dangerous cities in the United States, along with several other cities in the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area, such as Camden, Trenton, and Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Chester, Pennsylvania. In the 2000s, while most cities had seen a decrease in crime and murder, Wilmington had broken its record for homicides in a single year multiple times. In 2017, Wilmington saw an even steeper increase in crime. By August 2017, Wilmington had already eclipsed the homicide total of 2016 despite only being 2/3 through the year.[61] In 2014, Wilmington recorded 28 homicides, making for a rate of 39.5 per 100,000 residents, which is ten times the national average.[62] Wilmington frequently appears on NeighborhoodScout's "Top 100 Most Dangerous Cities in the United States" list. In 2017, Wilmington was ranked as the 5th most dangerous city in the US.[63] Nearby cities such as Camden, New Jersey, and Chester, Pennsylvania, also ranked in the top 15. In early 2017, the mayor's office as well as many public advocates called for comprehensive action to reduce astronomical crime rates in Wilmington, as the city saw a shooting almost every other day throughout the spring, and by May, the city had already seen 15 homicides. According to the WPD's 2018 Compstat report, shooting incidents have decreased to a level not seen in Wilmington in more than 15 years. When compared to the average number of shooting incidents from 2003 through 2017, which is 108, the 72 shooting incidents in 2018 represent a 33% decrease over the 15-year period average.[64]

Police

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

The Wilmington Police Department (WPD), is authorized to deploy up to 289 officers in motor vehicles, on foot, and on bicycle. Its operations are accredited by the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies. As of 2023, its chief of police is Wilfredo Campos.[65]

In 2002, the Wilmington Police Department started a program known to some in the neighborhoods as jump-outs in which unmarked police vans would patrol crime-prone neighborhoods late at night, suddenly converge at street corners where people were loitering and detain them temporarily. Using loitering as probable cause, the police would then photograph, search, and fingerprint everyone present. Along with apprehending anyone with drugs or weapons, it was thought that this program would improve the police's database of fingerprints and eye-witnesses for use in future crime investigations. Some citizens protested that such a practice was a violation of civil rights.[66]

Also in 2002, the entire downtown business district was placed under video monitoring. Wilmington was the first city in the United States to monitor the entire business district using video monitoring. The city claims this has helped prevent and reduce crime.[67]

Fire department and EMS

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

The Wilmington Fire Department (WFD) is led by Chief John Looney[68] and maintains five engine companies, two ladder companies, a rescue squad company, and a marine company (fireboat) fire fighting fleet.

Emergency medical services are provided through contract with the city's St. Francis Hospital, whose EMS division operates a minimum five BLS transport units at all times of the day. Advanced Life Support services in the City of Wilmington are provided by New Castle County's EMS Division with two city-based medic units. All Wilmington firefighters since 2002 are trained to the EMT-B level and serve as first responders for life-threatening emergencies.

Economy

editMuch of Wilmington's economy is based on its status as the most populous and readily accessible[weasel words] city in Delaware, a state that made itself attractive to corporations with business-friendly financial laws and a longstanding reputation for a fair and effective[weasel words] judicial system.[citation needed] Contributing to the economic health of the downtown and Wilmington Riverfront regions has been the presence of Wilmington Station, through which 665,000 people passed in 2009.[69]

Wilmington has become a national financial center for the credit card industry, largely due to regulations enacted by former Governor Pierre S. du Pont IV in 1981. The Financial Center Development Act of 1981, among other things, eliminated the usury laws enacted by most states, thereby removing the cap on interest rates that banks may legally charge customers. Major credit card issuers such as Barclays Bank of Delaware (formerly Juniper Bank), are headquartered in Wilmington. The Dutch banking giant ING Groep N.V. headquartered its U.S. internet banking unit, ING Direct (now Capital One 360), in Wilmington. Wilmington Trust is headquartered in Wilmington at Rodney Square. Barclays and Capital One 360 have very large and prominent locations along the waterfront of the Christina River. In 1988, the Delaware legislature enacted a law which required a would-be acquirer to capture 85 percent of a Delaware chartered corporation's stock in a single transaction or wait three years before proceeding. This law strengthened Delaware's position as a safe haven for corporate charters during an especially turbulent time filled with hostile takeovers.[weasel words]

Wilmington's other notable industries include insurance (American Life Insurance Company [ALICO], Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Delaware), retail banking (including the Delaware headquarters of: Wilmington Trust (now a branch of M&T Bank, after Wilmington Trust merged with M&T in 2011), PNC Bank, Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase, HSBC, Citizens Bank, Wilmington Savings Fund Society, and Artisans' Bank), and legal services. A General Motors plant was closed in 2009.[70] Wilmington is home to one Fortune 500 company, E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company.[71] Science and Technology are also thriving as companies such as Incyte, Chemours, Corteva, Solenis and ZipCode call Wilmington home.[72] In addition, the city is the corporate domicile of more than 50% of the publicly traded companies in the United States, and over 60% of the Fortune 500.[citation needed]

Delaware chartered corporations rely on the state's Court of Chancery to decide legal disputes, which places legal decisions with a judge instead of a jury. The Court of Chancery, known both nationally and internationally for its speed, competence, and knowledgeable judiciary as a court of equity,[73] is empowered to grant broad relief in the form of injunctions and restraining orders, which is of particular importance when shareholders seek to block or enjoin corporate actions such as mergers or acquisitions. The Court of Chancery, as a statewide court, may hear cases in any of the state's three counties. A dedicated-use Chancery courthouse was constructed in 2003 in Georgetown, Sussex County.[74] It has hosted high-profile complex corporate trials such as the Disney shareholder litigation.

Because Delaware is the official state of incorporation for so many American companies, the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware, located in Wilmington, is one of the busiest of the 94 federal bankruptcy courts located around the United States.

Delaware has among the strictest rules in the U.S. regarding out-of-state legal practice, allowing no reciprocity to lawyers who passed the bar in other states.[75]

Top employers

editAccording to Wilmington's 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[76] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | State of Delaware | 14,199 |

| 2 | ChristianaCare | 11,308 |

| 3 | University of Delaware | 4,493 |

| 4 | Amazon (DE Fulfillment Centers) | 4,300 |

| 5 | Nemours (Nemours Children's Hospital, Delaware) | 3,795 |

| 6 | DuPont Company | 3,500 |

| 7 | AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP | 2,500 |

| 8 | YMCA of Delaware | 2,469 |

| 9 | Christina School District | 2,390 |

| 10 | Red Clay School District | 2,200 |

| 11 | Delaware Technical Community College | 2,100 |

| 12 | New Castle County Government | 2,000 |

| 13 | M&T Bank (Wilmington Trust Corp.) | 1,900 |

| 14 | Brandywine School District | 1,472 |

| 15 | Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics | 1,410 |

| 16 | Connections Community Support | 1,200 |

| 17 | St. Francis Healthcare | 1,200 |

| 18 | Delaware State University | 1,009 |

| 19 | The Chemours Company | 1,000 |

| 20 | Wilmington VA Medical Center | 980 |

| 21 | Delmarva Power | 898 |

| 22 | AAA | 890 |

| 23 | Blackrock Capital Management, Inc. | 834 |

| 24 | WSFS Bank | 801 |

In terms of growth, as of 2018[update] the city was seeing nearly $450M worth of private investments,[how often?] multi-million dollars of city infrastructure improvements, and significant improvements to their transportation infrastructure.[77]

Arts and culture

editWilmington has many museums, galleries, and gardens (see Points of Interest below), as well as many ethnic festivals and other events throughout the year. Notable among its museums is the Delaware Art Museum whose collection focuses on American art and illustration from the 19th to the 21st century, and on the English Pre-Raphaelite movement of the mid-19th century.

Ethnic festivals

editWilmington has an active and diverse ethnic population, which contributes to several ethnic festivals held every spring and summer in Wilmington, the most popular of which is the Italian Festival. This event, run by St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church, closes down six blocks in the west side of the city the second week of June for traditional Italian music, food, and activities, along with carnival rides and games. Another, somewhat smaller festival that draws large crowds is the Greek Festival, which is organized by Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church. The event features traditional Greek (Hellenic) crafts, food, drink, and music. Another notable annual festival is the Polish festival organized by St. Hedwig's Catholic Church, which features Polish cuisine with carnival rides and entertainment. Haneef's African Festival celebrates the heritage of the African American majority in the city.[78] Wilmington is also home to the annual Big August Quarterly, which since 1814 has celebrated African American religious freedom. IndiaFest, another cultural festival, is hosted by the Indo American Association of Delaware.[79] Wilmington also celebrates Hispanic Week, which coincides with National Hispanic Month festivities, September 15 – October 15. The festival culminates with a pageant and desfile (parade) along 4th Street. Concerts featuring Latin music acts, Latin cuisine and a carnival are held on the Riverfront on the last weekend. Activities are also held at St. Paul's Catholic Church.

Music festivals

editThe Clifford Brown Jazz Festival is a week-long outdoor music festival held each summer in Wilmington's Rodney Square.

The Peoples' Festival is an annual tribute to Bob Marley, who once lived in Wilmington trying to earn money enough to establish his Tuff Gong music studio in Kingston, Jamaica. His son Stephen Marley was born in Wilmington 1972. Started in 1994, the Peoples' Festival features reggae and world beat musicians playing original music and Bob Marley and the Wailers songs. The festival is held on the Wilmington riverfront each summer.

The Riverfront Blues Festival, a three-day music festival held each August in the Tubman-Garrett Riverfront Park, features prominent blues acts as well as artists from the local area.

Holiday events

edit- Annual tree-lighting ceremony related to the Christmas holiday at Rockwood Museum and Park[80]

- The Nutcracker performed by the Wilmington Ballet at the Playhouse at the Hotel DuPont

- Wilmington's memorial day parade is the oldest continuous parade in the country[81]

Wilmington Riverfront

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

In the 1990s, the city launched a campaign to revitalize the former shipyard area known as the Wilmington Riverfront. Delaware Theatre Company was at the forefront of this movement, opening its current space on Water Street in 1985.[82] The efforts were bolstered early by The Big Kahuna also known as Kahunaville (a restaurant, bar and arcade which has also since closed and been rebuilt in 2010 as the Delaware Children's Museum) and Daniel S. Frawley Stadium, the Wilmington Blue Rocks minor league baseball stadium. The Chase Center on the Riverfront opened as the First USA Riverfront Arts Center in 1998 to hold traveling exhibitions, but was repurposed into the city's convention center in 2005. The Wilmington Rowing Center boathouse is located along the Christina River on the Riverfront. Development continues as the Wilmington Riverfront tries to establish its cultural, economical, and residential importance. Recent high-rise luxury apartment buildings along the Christina River have been cited as evidence of the Riverfront's continued revival. On June 7, 2006, the groundbreaking of Justison Landing signaled the beginning of Wilmington's largest residential project since Bancroft Park was built after World War II. Outlets shops, restaurants and a Riverfront Market have also opened along the 1.2-mile (1.9 km) Riverwalk.

Media

editRadio and television

editThe Wilmington area is home to five FM radio stations and four AM radio stations. A sixth FM radio station is located in Southern New Jersey and is included in the Wilmington radio market surveys:

- 91.3-FM WVUD—Non-commercial radio (University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware)

- 91.7-FM WMPH—Non-commercial high school radio

- 93.7-FM WSTW—Pop contemporary hits

- 96.9-FM W245CJ—Hispanic format

- 99.5-FM WVCW—Christian

- 101.7-FM WDEL-FM—News Talk Information (Canton, New Jersey)

- 103.7-FM WXCY-FM—Country

- 1150-AM WDEL—News Talk Information

- 1290-AM WWTX—Sports talk

- 1380-AM WTMC—Travel Information

- 1450-AM WILM—News Talk Information

Additionally, many radio stations from Philadelphia reach Wilmington. Wilmington is part of the Philadelphia television market. Three of the market's stations are licensed to Wilmington: WPPX, WDPN-TV, and WHYY-TV.

Newspaper

edit- The News Journal, founded as the Delaware Gazette in 1785. Daily circulation as of 2004 and 2007 exceeded 100,000, placing the newspaper among the top 100 in the United States, based on circulation.[83][84]

- Wilmington Sunday Star (1881–1954)[85]

- WilmToday, founded in 2016 to cover the latest news, posts, and all of the great things about the city of Wilmington.

Portrayal of Wilmington in popular culture

edit- Wilmington's skyline and other aerial shots of the city stood in for the fictional town of Arcadia in the television program Joan of Arcadia.[86]

- The 1999 film Fight Club (adapted from Chuck Palahniuk's novel of the same title) is set in Wilmington. City officials rejected the filmmakers' request to film in Delaware, so the movie's exterior shots were filmed in Los Angeles.[citation needed]

- Saturday Night Live (SNL) skits portraying Joe Biden often mention his residency in Wilmington. For example, in the cold opening of the May 12, 2012, episode, Biden pouts in his Washington, D.C., bedroom, which features an aerial picture of the downtown Wilmington skyline with "DELAWARE" printed along the bottom.[87]

- In November 2015, ABC announced a pilot for a legal drama starring Jada Pinkett Smith set in the Wilmington. The show would have been called Murder Town. Mayor Dennis Williams reacted strongly, calling the actors in the show "has beens". The pilot was passed over by ABC in August 2016.[88][89]

Transportation

editHighways

editInterstate 95, which splits Wilmington roughly into eastern and western halves, provides access to major markets in the Northeast and nationwide. Interstate 495 is a bypass passing through the east side of the city, and Interstate 295 is south of the city, crossing the Delaware River into New Jersey on the Delaware Memorial Bridge. U.S. Route 13 passes north–south through the eastern part of Wilmington, entering the city from the south along Dupont Highway before following Heald Street, the one-way pair of Church Street northbound and Spruce Street southbound, and Governor Printz Boulevard. U.S. Route 13 Business passes north–south through the center of Wilmington, entering the city from the south on Market Street before splitting into Walnut Street northbound and Market Street southbound, following Walnut Street northbound and King Street southbound in the downtown area, and following Market Street northeast out of the city to Philadelphia Pike. U.S. Route 202 follows I-95 through Wilmington before heading north onto Concord Pike through a business area to the north of the city. State routes serving Wilmington include Delaware Route 2, which follows the one-way pair of Lincoln Street eastbound and Union Street westbound in the western part of the city before heading west out of the city along Kirkwood Highway; Delaware Route 4, which heads southwest from the downtown area along Maryland Avenue; Delaware Route 9, which enters the city from the south along New Castle Avenue before crossing the Christina River and heading west through the center of the city along 4th Street; Delaware Route 9A, which provides access to the Port of Wilmington; Delaware Route 48, which heads west from the downtown area along Lancaster Avenue; Delaware Route 52, which follows Delaware Avenue and Pennsylvania Avenue northwest out of the city to Kennett Pike; and Delaware Route 202, which follows Concord Avenue through the northern part of the city to connect to US 202 at Concord Pike.[90]

In Wilmington, streets are laid out in a grid, with north–south streets named and east–west streets north of Lancaster Avenue/Front Street numbered from 2nd Street and increasing to the north, while east–west streets south of Lancaster Avenue/Front Street are named. Lancaster Avenue/Front Street serves as the divider between north and south while Market Street serves as the divider between east and west.[90] There are 34 red light cameras in the city of Wilmington situated at 31 intersections.[91] Parking in downtown Wilmington is regulated by on-street parking meters along with commercial parking lots and parking garages operated by the Wilmington Parking Authority, Colonial Parking, and SP Plus Corporation.[92]

Railroads

editWilmington is served by the Joseph R. Biden Jr. Wilmington Rail Station, with frequent service between Boston, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C., via Amtrak's Northeast Corridor. SEPTA Regional Rail provides frequent additional local commuter rail service to Philadelphia along the Wilmington/Newark Line. Amtrak has a major maintenance shop and yard in northeast Wilmington that maintains and rebuilds the agency's Northeast Corridor electric locomotive fleet. The Amtrak Training Facility is also located in Wilmington, as well as Amtrak's Consolidated National Operations Center (CNOC).[93]

Two freight railroads, CSX and Norfolk Southern, also serve Wilmington. Norfolk Southern serves Wilmington along trackage rights on Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, the Shellpot Secondary line heading through the eastern part of Wilmington as a bypass of the Northeast Corridor, and the New Castle Secondary line heading south to New Castle and Porter. CSX serves Wilmington along its Philadelphia Subdivision line running between Philadelphia and Baltimore. Both CSX and Norfolk Southern have a major freight-yard in the area; CSX operates the Wilsmere Yard to the west of the city in Elsmere and Norfolk Southern operates the Edgemoor Yard to the northeast of the city in Edgemoor.[93]

Buses

editDART First State operates public bus service with approximately 30 bus lines serving the city and the surrounding suburbs as well as inter-county service to Dover, the state capital, and seasonal service to Lewes. Many DART First State bus routes operating in Wilmington serve Wilmington Transit Center and/or Rodney Square, the main bus transit hubs in the city.[94] Greyhound Lines operates interstate bus service out of the Wilmington Bus Station at the rail station.[95]

Airports

editWilmington Airport (ILG) is located a few miles south of downtown, and offers scheduled passenger service operated by Avelo Airlines. Wilmington Airport also serves as a base for both the Delaware Army National Guard and Delaware Air National Guard. The closest major international airport is Philadelphia International Airport (PHL).

Seaport

editWilmington is also served by the Port of Wilmington, a modern full-service deepwater port and marine terminal handling over 400 vessels per year with an annual import/export cargo tonnage of 5 million tons. The Port of Wilmington handles mostly international imports of fruits and vegetables, automobiles, steel, and bulk products.

Infrastructure

editUtilities

editDelmarva Power, a subsidiary of Exelon, provides electricity and natural gas to Wilmington.[96][97] The city's Department of Public Works provides water and sewer service to Wilmington and some surrounding unincorporated areas.[98][99] The city's water supply comes from the Hoopes Reservoir to the northwest of the city and from a dam along the Brandywine Creek in the city, with water mains pumping the water from these sources to facilities in the city, where the water is treated and stored or distributed to customers.[100] The city's Department of Public Works also provides trash collection and recycling to Wilmington.[101]

Health care

editChristiana Care Health System, a health network headquartered in Wilmington, runs Wilmington Hospital on the edge of downtown Wilmington and Christiana Hospital in suburban Christiana, as well as various satellite health centers throughout the area. St. Francis Hospital, a member of Trinity Health, is located in the west end of Wilmington. The Nemours Foundation runs Nemours Children's Hospital, Delaware in North Wilmington, just outside the city proper.

The city has one of the highest per capita rates of HIV infection in the United States, with disproportionate rates of infection among African-American males.[102][103] Efforts by local advocates to create needle exchange programs to reduce the spread of infection were obstructed for several years by downstate and suburban state legislators but a program was finally approved in June 2006.[104]

Sports and recreation

editSports

edit| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Founded | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delaware Blue Coats | Basketball | NBA G League | Chase Fieldhouse | 2013 | (1) 2023 |

| Wilmington Blue Rocks | Baseball | MiLB (High-A East) | Frawley Stadium | 1993 | (5) 1994, 1996, 1998, 1999, 2019 |

| Delaware Black Foxes | Rugby league | USARL | Eden Park Stadium | 2015 | None |

| Bearfight FC of Wilmington | Soccer | United States Adult Soccer Association | Traveling Team | 2013 | None |

| Wilmington Rugby Football Union | Rugby Union | USA Rugby | Alapocas Run | 1974[105] | None |

The Wilmington Blue Rocks, a Minor League Baseball team affiliated with the Washington Nationals, plays at Daniel S. Frawley Stadium.

The stadium is also the home of the Delaware Sports Museum and Hall of Fame.

Since their founding in 2015, the USA Rugby League expansion club Delaware Black Foxes have been based in the city at Eden Park Stadium.

In 2013, Bearfight FC of Wilmington was founded as the only United States Adult Soccer Association hailing from Delaware, qualifying them as the sole representative of The First State in the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup.

Outdoor recreation

editThe Wilmington State Parks are a group of four parks in Wilmington operated by the Delaware State Park system. The four parks are Brandywine Park, including the Brandywine Zoo and Baynard Stadium, Alapocas Woods Natural Area, H. Fletcher Brown Park and Rockford Park. Admission to the parks is free, but a fee is charged for admittance to the zoo. The parks, within minutes of each other, are open year-round from sunrise to sunset. The zoo is open daily from 10:00 am until 4:00 pm, May through November. Rockford Tower and Rockford Park is open from 10:00 am until 4:00 pm on Saturdays and Sundays, from May 1 until October 31. The parks are patrolled by Delaware State Park Rangers whose headquarters office is in Brandywine Park.[106]

The City of Wilmington also operates 55 parks and recreational facilities across the city.

Running events

editThe Delaware Distance Classic is a 15K road race held in October by the Pike Creek Valley Running Club (PCVRC). The course has rotated every few years based on sponsorship and is currently located in nearby Delaware City. The event began in 1983 as a fundraiser for the PCVRC, and the Mike Clark Legacy Foundation has been the beneficiary for the last few years.

The Caesar Rodney Half Marathon is a 21.0975-kilometre (13.1094 mi) road race held annually since 1964 on the second Sunday in March.[107] Billed by race organizers as the "granddaddy of Delaware road races", it generally draws more than 1,000 runners from 20 states and several countries. From the starting line at Wilmington's Rodney Square, runners flow past the scenic revitalized riverfront, through Rockford Park and back to Rodney Square at the Caesar Rodney statue. Proceeds benefit the American Lung Association of Delaware.[108]

The Run for the Buds 1/2 Marathon, 1/2 Marathon Relay, and 5K Run/Walk is held annually at Rockford Park in mid-October. Proceeds benefit people with intellectual disabilities through the Down Syndrome Association of Delaware.[109]

Cycling

editThe Wilmington Grand Prix is held annually and is considered one of the premier criterium-style bike races in the country. Now in its 11th year, it is part of USA Cycling's National Race Calendar, a collection of only the most elite races. Weekend festivities include a street festival, a time trial on Monkey Hill, criterium races in downtown Wilmington at both the amateur and pro level, a 50 km Media Fondo, a 100 km Gran Fondo, and a leisurely Governor's Ride.[110]

Additionally, the East Coast Greenway passes through Wilmington and its immediate suburbs for 10.4 miles as part of the scenic Northern Delaware Greenway, which includes steep hills, heavily forested sections and paved portions that lead through downtown.[111][112]

Golf

editThe Wilmington Country Club is a country club and golf course located just outside of the city in a suburb known as Greenville. .[113]

Ed "Porky" Oliver Golf Club is a public course located within the city limits.[114]

Rock Manor is a public course located just outside of the city limits.[115]

Tennis

editThe Delcastle Tennis Center is a tennis center located in the city.[116]

Education

editPrimary and secondary schools

editPublic schools

editWilmington is served by the Brandywine, Christina, Red Clay, and Colonial school districts for elementary, junior high, and high school public education.[117] Of those four, Colonial is the only one which has no schools located in the Wilmington city limits.[118] Cab Calloway School of the Arts of the Red Clay district is in the Wilmington city limits. The New Castle County Vocational-Technical School District operates Howard High School of Technology in the city of Wilmington.

As of 2020[update] there are no comprehensive traditional public high schools in the Wilmington city limits, and most high school-aged students in the city attend high schools in suburban areas away from the city. Cris Barrish and Mark Eichmann of WHYY wrote that these suburban comprehensive high schools "struggle academically".[119]

Wilmington also hosts several charter schools. As of November 2015[update] there were 11 charter schools in the city limits.[118] These include the Charter School of Wilmington, Great Oaks Charter School, Kuumba Academy Charter School, East Side Charter School, and a magnet school, Cab Calloway School of the Arts which focuses on the performing arts. The Charter School of Wilmington and Cab Calloway School of the Arts are housed in the building of the former Wilmington High School. Great Oaks Charter School and Kuumba Academy are housed in the Community Education Building (a/k/a "C.E.B"), formerly known as Bracebridge IV, acquired by Bank of America from MBNA Corp. in 1997 and donated to The Longwood Foundation in 2012.[120]

Historically Wilmington High School, in the west of the city, and P.S. du Pont High School, in the north of the city, were schools for white children while Howard High School, in the east of the city, was the segregated school for black children.[119] In 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court forced the then segregated schools of New Castle County to desegregate. However, the subsequent eleven school districts that were created in the county, including the Wilmington School District, soon became de facto segregated, as the Wilmington School District became predominately black, and the districts outside the city remained overwhelmingly white.[citation needed] A 1968 law from the Delaware General Assembly prevented a merger between the Wilmington district and other districts as the law prevented a merger involving a school district with over 12,000 pupils. In 1969 Wilmington, du Pont, and Howard were the three comprehensive high schools in Wilmington.[119]

In response to the segregation, the 1976 U.S. District Court decision Evans v. Buchanan implemented a plan by which students in Wilmington would be bused to attend school in the suburbs for certain grades, while suburban students would be bused into the City of Wilmington for other grades. By 1981,[citation needed] the four current districts in northern New Castle County, Brandywine, Christina, Colonial, and Red Clay, each composed of city and suburban areas, were established, all of which were majority white at the time. The idea was that no one district would be majority poor, black, and disadvantaged. Wilmington High remained in operation under the Red Clay district until 1999 and it now houses Calloway School of the Arts. Howard High became Howard High School of Technology, and P.S. du Pont became an elementary school of the Brandywine district. University of Delaware public policy professor Leland Ware wrote that Wilmington parents were divided, with many African-Americans preferring children be educated in the city while others liked the idea of their children attending integrated schools. According to Ware suburban parents generally disliked their children being bussed into Wilmington for desegregation as suburbanites perceived Wilmington as being unsafe.[119]

In 2015, Mark Murphy, Delaware's secretary for Education, expressed support for re-establishing a comprehensive high school in Wilmington.[121] In 2020, there were persons in Wilmington, including the mayor Mike Purzycki, advocating for this as well. Such a school would be majority African-American. Purzycki stated that fear of racial resegregation is the issue that causes community stakeholders to be reluctant to do so.[119]

Private schools

editThere are many private elementary and secondary schools in Wilmington:[122] Salesianum School, Serviam Girls Academy, Nativity Preparatory of Wilmington,[123] Ursuline Academy, Tower Hill School, St. Elizabeth High School, and Padua Academy. With 17.6% of the area students enrolled in private schools, the Wilmington area ranks as one of the top ten metropolitan areas in the country for the percentages of students in private school.[124]

The Tatnall School and Wilmington Friends School have Wilmington postal addresses but are located outside of the city limits

Universities and colleges

editThere are several colleges operating in the city of Wilmington:

- Delaware College of Art & Design

- Delaware State University – Wilmington Campus

- Delaware Technical & Community College – Wilmington Campus

- Goldey-Beacom College

- University of Delaware – Wilmington Campus and Downtown Building

- Wilmington University – Wilmington Campus

- Widener University Delaware Law School

Places of interest

edit- Brandywine Zoo[125]

- Delaware Art Museum

- Delaware Center for the Contemporary Arts[126]

- Delaware Center for Horticulture

- Delaware Children's Museum

- Delaware Children's Theatre

- Delaware Historical Society

- Delaware Sports Museum and Hall of Fame

- Delaware Theatre Company[127]

- DuPont Playhouse

- Frank Furness Railroad District, a collection of railroad buildings designed by Frank Furness

- Fort Christina State Park

- Grand Opera House

- Kalmar Nyckel Foundation & Tall Ship

- Holy Trinity (Old Swedes') Church

- Riverfront Market

- Rockford Tower

- Rodney Square

- Wilmington and Brandywine Cemetery

- Wilmington Blue Rocks, South Atlantic League baseball

- Wilmington Drama League[128]

- The Wilmington Library[129]

- Wilmington Riverfront

- Wilmington State Parks, which includes Brandywine Park[130]

Sister cities

editWilmington has six sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:[131]

- Fulda, Germany

- Kalmar, Sweden

- Olevano sul Tusciano, Salerno, Campania, Italy

- Osogbo, Nigeria

- Watford, Hertfordshire, England, United Kingdom

Partner city

edit- Nemours, Seine-et-Marne, Île-de-France, France

Notable people

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ Min, Shirley (December 7, 2012). "New signs welcome folks to Delaware's largest city". WHYY-FM News. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "Wilmington". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Lenape Talking Dictionary". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Delaware". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016". 2016 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2017. Archived from the original (CSV) on February 14, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ "Svenska präster genom tiderna". Geni.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ Munroe, John A. (1978), Colonial Delaware: A History, A History of the American colonies, Millwood, New York: KTO Press, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-527-18711-8, OCLC 3933326

- ^ McCormick, Richard P. (1964), New Jersey from Colony to State, 1609–1789, New Jersey Historical Series, vol. 1, Princeton, New Jersey: D. Van Nostrand Co., p. 12, OCLC 477450

- ^ Scharf, J. Thomas (1888), "XXIV. Medicine and medical men", History of Delaware, 1609–1888, vol. 1, Philadelphia: L. J. Richards, p. 471, hdl:2027/mdp.39015011346874, LCCN 01013423, OCLC 454559306, archived from the original on August 20, 2014, retrieved May 14, 2011

- ^ Stidham, Jack (2001), "The descendants of Dr. Timothy Stidham" (PDF), Swedish Colonial News, vol. 2, no. 5, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Swedish Colonial Society, p. 16, OCLC 37868632, archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2011, retrieved May 14, 2011

- ^ Munroe, John A. (2006), "The Lower Counties on the Delaware", History of Delaware (5th ed.), Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press, p. 57, ISBN 0-87413-947-3, OCLC 68472272,

Originally, the new community was called Willingtown, after Thomas Willing, an English merchant who settled there and began selling town lots in 1731 after marrying the daughter of a Swedish landowner, Andrew Justison

- ^ Justison, Willing's father-in-law, purchased the land from the family of Samuel Peterson.

- ^ Ferris, Benjamin (1846). "Part III. Chapter II. History of Wilmington" (eBook). A History of the Original Settlements on the Delaware from its Discovery by Hudson to the Colonization under William Penn. Wilmington, Delaware: Wilson & Heald (eBook: The Darlington Digital Library). p. 202. OCLC 124509564. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ "First Powder Mill: 1802". DuPont home, English-US version. Wilmington, Delaware: DuPont. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved January 9, 2010. Archive attempt via WebCitation.org failed May 14, 2011.

- ^ "The DuPont Company". Delaware History Online Encyclopedia. Wilmington, Delaware: Delaware Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Boyer, William W. (2000), "Chapter Three: The Governor as Leader", Governing Delaware: Policy Problems In The First State (eBook), Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press (eBook: Google), p. 57, ISBN 0-87413-721-7, OCLC 609154858, archived from the original on June 6, 2013, retrieved May 14, 2011

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Wilmington New Castle CO AP, DE". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Wilmington city, Delaware". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "1980 census" (PDF). Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ "Delaware: 1990" (PDF). Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Wilmington city, Delaware". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Wilmington city, Delaware". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Wilmington city, Delaware". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Wilmington (city), Delaware". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ "Delaware – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ "2010 SF1 Data for Wilmington, Delaware". City-Data. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 21, 2019. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ "2010 SF1 Data for Wilmington, Delaware". City-Data. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ "Wilmington mayor, City Council inauguration Tuesday". Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Council Members – Wilmington City Council". Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Howard R. Young Correctional Institution". Delaware Department of Correction. State of Delaware. August 18, 2010. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Chalmers, Mike (May 14, 2011). "Unions' pact with Wilmington saves 235 jobs". The News Journal. New Castle, Delaware: Gannett. DelawareOnline. Archived from the original on May 25, 2024. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "Wilmington Neighborhoods" (PDF). City of Wilmington, Delaware. February 14, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 30, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ "Brandywine Hills". Neighborhood Link. September 22, 2010. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Greater Brandywine Village". Greater Brandywine Village. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "The Triangle Neighborhood Association". Wilmington, Delaware. 2009. Archived from the original on March 9, 2009.

- ^ "Midtown Brandywine Neighbors Association". Neighborhood Link. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Quaker Hill Historic Preservation Foundation". Quaker Hill Historic Preservation Foundation. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Wilmington Monthly Meeting of Friends". Wilmington Friends Meeting. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Riverfront Wilmington". Riverfront Development Corporation. June 26, 2010. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Trinity Vicinity.org Website". Trinity Vicinity Neighborhood Association. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "11th Street Bridge Civic Association". Neighborhood Link. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "Hedgeville Community Association". Neighborhood Link. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Canby, William Marriott (1831–1904)". JSTOR, Global Plants. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "Co-ed and Single Sex". Ursuline Academy. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Padua Academy: About Us". Padua Academy. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Neighborhoodlink.com". Neighborhood Link. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ Staub, Andrew (August 17, 2013). "After demolition, a neighborhood reborn". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ^ "Forty Acres Civic Association". Neighborhood Link. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "Hilltop Neighborhood Working Group". Community Services: Neighborhoods. City of Wilmington. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ Harris, Richard J; O'Connell, John P; Mande, Mary J; Kane, James (September 1999). "Evaluation of Operation Weed & Seed in Wilmington, Delaware" (PDF). State of Delaware Document Number 100703-990904. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ "Welcome to Little Italy". Little Italy Neighborhood Association. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Xerxes (March 17, 2023). "Hunter Biden is suing Trolley Square laptop repairman at center of data leak". The News Journal. New Castle, Delaware.

- ^ "Trolley Square Delaware Shopping, Activities, Events". Trolley Square Merchant Association. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ Ruminski, Clayton (September 22, 2016). "Trolley Square, Wilmington's Streetcar System, and the Delaware Coach Company". Hagley Museum and Library.

- ^ "Wawaset Park Maintenance Corp". Neighborhood Link. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Union Park Gardens". Neighborhood Link. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "City Historic Districts". Community Services. City of Wilmington. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Encouraged, Hopeful and Committed: Public Safety in Wilmington Improved Greatly in 2018". WilmToday. January 11, 2019. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ "Wilmington Shootings". data.delawareonline.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ "Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics". www.ucrdatatool.gov. Retrieved August 15, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Top 100 most dangerous places to live in the USA - NeighborhoodScout". NeighborhoodScout. January 1, 2017. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ "COMPSTAT REPORTS". City of Wilmington, DE. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ "Department of Police". City of Wilmington. Archived from the original on April 9, 2023. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (August 25, 2002). "Wilmington police photo policy under fire". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE: The News Journal Co. Archived from the original on September 1, 2002. Retrieved October 30, 2009.