Tel Rehov (Hebrew: תל רחוב) or Tell es-Sarem (Arabic: تل الصارم), is an archaeological site in the Bet She'an Valley, a segment of the Jordan Valley, Israel, approximately 5 kilometres (3 mi) south of Beit She'an and 3 kilometres (2 mi) west of the Jordan River. It was occupied in the Bronze Age and Iron Age.

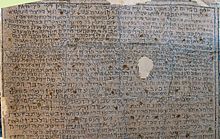

"Mosaic of Rehob" from the synagogue at Khirbet Farwana/Horvat Parva near Tel Rehov | |

| Coordinates | 32°27′26″N 35°29′54″E / 32.457125°N 35.498242°E |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Founded | circa 14th century BC |

| Abandoned | circa 7th century BC |

| Periods | Bronze Age, Iron Age |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1997 to 2012 |

| Archaeologists | Amihai Mazar |

The site is one of several suggested as Rehov (also Rehob), meaning "broad", "wide place".[1]

The oldest apiary discovered anywhere by archaeologists, including man-made beehives and remains of the bees themselves, dating between the mid-10th century BCE and the early 9th century BCE, came to light on the tell. In the nearby ruins of the mainly Byzantine-period successor of Iron Age Rehov, a Jewish town named Rohob or Roōb, within it a synagogue with the Mosaic of Rehob, considered one of the most important discoveries from the Roman - Byzantine period and the longest mosaic inscription found so far in the Land of Israel.[2][3]

Identification

editTel Rehov does not correspond to the Hebrew Bible places named as Rehov, of which two were in the more westerly allotment of the Tribe of Asher, and one more northerly.[4]

Identification of Tell es-Sarem/Tel Rehov with the ancient Canaanite and Israelite city of Rehov was based on the preservation of the name at the nearby Islamic holy tomb of esh-Sheikh er-Rihab (one kilometre; 1000 yards to the south of Tel Rehov), and the existence of the ruins of a Byzantine-period Jewish town that preserved the old name in the form of Rohob or Roōb/Roob (one kilometre; 1000 yards northwest of Tel Rehov).[5][6][7]

Rehov was one of the largest cities in the region during the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BCE) and Iron Age I–IIA (1200–900 BCE).[5] During the Late Bronze Age, while Egypt ruled over Canaan, Rehov was mentioned in at least three sources dated between the 15th–13th century BCE, and again in the list of conquests of Pharaoh Shoshenq I, whose campaign took place around 925 BCE.[5]

History

editBronze Age

editExcavations revealed an eight meter wide mud brick fortification wall (with glacis) around the upper mound which the excavators attributed to the Early Bronze III period though no city of that period was found. The site was clearly occupied during the Late Bronze I and Late Bronze II periods, from 15th century BC to 13th century BC. Actual occupation from this period was found only on a small area (Area D) of the lower mound with possible exposure in probes on the upper mound. Some Egyptian material, including a scarab with the inscription "Scribe of (the) house of (the) overseer of sealed items, Amenemhat" indicates the town may have been under Egyptian control like other towns in the region, after the time of Thutmose III.

Iron Age

editThe site was occupied in the Iron Age I and Iron Age II periods, from 12 century BC to 9th century BC. At that point it was destroyed and burnt which the excavators ascribe to the Assyrians in the mid-800s BC.

In the Levant there is a large Iron Age chronology controversy (similar the even more complicated Chronology of the ancient Near East with which there is some overlap). It is all very tangled with a High Chronology and a Low Chronology and some variants thereof. Given the careful stratigraphy and many radiocarbon dates Tel Rehov has been used to support and deny various chronologies.[8][9][10][11] It has also been identified as a Lowland power center in opposition to the Omrides.[12]

Greek pottery

editFrom the 10th century BC and 9th century BC (Strata VI to IV) Greek pottery was found in stratified context. This is a useful result in addressing the chronology problems of the Levant (High vs Low) and of Greek pottery.[13]

"Elisha" ostracon

editIn 2013, a potsherd was found holding a partially preserved inscription, which has been reconstructed as to be the rare name of Elisha, best known as the name of biblical Prophet Elisha. [14] The association with the prophet is tenuous, based on the date of the ostracon (the second half of the ninth century), the rarity of the name, and the geographic vicinity of Elisha's biblical hometown, Abel-meholah; but the name reconstruction is disputed, and the presence of incense altars in the house of the find and throughout Tel Rehov is considered contrary to the teachings of biblical prophets. [14]

Inscriptions

editIn and near Tel Rehov, inscriptions containing references to the family of Nimshi have been found.[14] King Jehu of the northern kingdom of Israel, anointed by a disciple of Elisha, is the son, grandson, or otherwise descendant of a certain Nimshi.[14]

Iron Age beehives

editThe oldest known archaeological finds relating to beekeeping were discovered at Rehov.[15][16]

In September 2007 it was reported that 30 intact beehives and the remains of 100–200 more dated to the mid-10th century BCE to the early 9th century BCE were found (Strata V, Area C) by archaeologists in the ruins of Rehov.[17] The hives had been destroyed by fire. The beehives were evidence of an advanced honey-producing beekeeping (apiculture) industry 3000 years ago in the city, then thought to have a population of about 2000 residents at that time, both Israelite and Canaanite. The beehives, made of straw and unbaked clay, were found in orderly rows of 100 hives.[18] Each individual beehive was shaped as a hollow cylinder measuring ca. 80 cm in length and 40 cm in diameter, with ca. 4 cm. thick wall.[16] One end of the cylinder was sealed, with only a small hole in its center that allowed the bees to enter and exit the hive.[16] Previously, references to honey in ancient texts of the region (such as the phrase "land of milk and honey" in the Hebrew Bible) were thought to refer only to honey derived from dates and figs; the discoveries show evidence of commercial production of bee honey and beeswax.

In addition to beehives, the remains of bees and bee larvae and pupae were also found. In 2010, using DNA from the remains of bees found at the site, researchers identified the bees as a subspecies, similar to the Anatolian bee, found now only in Turkey. It is possible that the bees' range has changed, but more likely that the inhabitants of Tel Rehov imported bees because they were less aggressive than the local bees and provided a better honey yield (three to eight times higher than Israel's native bees).[19]

Supporting archaeological knowledge include evidence of other imports in Rehov from eastern Mediterranean lands; later Egyptian documentation of transferring bees in large pottery vases or portable beehives; and an Assyrian stele from the 8th century BCE that evidences that bees had been brought from the Taurus Mountains of southern Turkey to the land of Suhu—about the same distance as between the Taurus and Rehov (400 kilometres (250 mi)).[19][20]

The beehives were dated by carbon-14 radiocarbon dating at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, using organic material (wheat found next to the beehives).

Ezra Marcus of the University of Haifa, said the finding was a glimpse of ancient beekeeping seen in Near Eastern texts and ancient art. Religious practice was evidenced by an altar decorated with fertility figurines found alongside the hives.[21][22][23]

Archaeology

editThe site of Tel Rehov consists of an upper and lower mound with a total area, including mound slopes, of 11 hectares (27 acres). The total area of the mound tops is 7 hectares (17 acres).

The site was inspected by W.F. Albright in the 1920s, identifying the main occupation period as being the 13th to 10th century BC.[24] In the 1940s Avraham Bergman and Ruth Brandstater inspected Tel Rehov. While there they found a Proto-Canaanite inscription in the topsoil.[25] In the following decades some local residents collected items from the site, including a cylinder seal from the Old Babylonian period.[26]

After full surface surveys and a geophysical study of the lower mound in 1995–1996 modern archaeological excavations were conducted for 11 seasons between 1997 and 2012 under the directorship of Amihai Mazar, Professor at the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and with the primary sponsorship of writer John Camp. Seven occupation strata were established with the uppermost (Strata I) representing scattered Islamic finds and the rest (Strata II to VII) being Iron Age. The lower mound was abandoned after Strata IV. No strata were established for the Bronze Age as results in this period were scanty and primarily on a small part of the lower mound.[27][28][29][30][31] Among the finds, recovered in the 2003 season, was a 10th century BC jar with 2 identical three letter Proto-Canaanite inscriptions.[32]

In 2002 a small rescue excavation occurred after ditching damaged several Bronze Age shaft tombs on the fringes of the site. Besides human remains, pottery fragments, ostrich egg-shell fragments, and two complete bronze daggers were found.[33]

Nearby sites

editAncient synagogue

editRemains of a mainly Byzantine-period synagogue built in three successive phases between the fourth and the seventh century CE were found at the site of Tulul Farwana ("mounds of Farwana"),[34] now part of the agricultural lands of Kibbutz Ein HaNetziv.[35] Among the remains of the synagogue archaeologists found a relatively well-preserved mosaic pavement, the narthex part of which includes a very long sixth-century inscription in Aramaic; the so-called Mosaic of Rehob, Tel Rehov inscription or Baraita of the Boundaries with details of Jewish religious laws concerning "the Borders of the Land of Israel" (Baraitha di-Tehumin), tithes and the Sabbatical Year.[36][34][37][38] During an archaeological survey of the abandoned structures standing at Farwana, there was found a marble-parapet with a relief of a seven-branched menorah, believed to have once enclosed the raised rostrum of the synagogue.[35] Today, the marble-parapet with its menorah relief is on display at the synagogue in Kibbutz Ein HaNetziv. Later, children from the kibbutz discovered nearby one of the abandoned structures a cache of gold coins, which discovery prompted a more thorough investigation of the site, under the tutelage of archaeologist Fanny Vitto.[35] An excavation of the site by her team led to the discovery of the aforementioned mosaic.[35]

Byzantine era town

editDuring the Byzantine era, a Jewish town that preserved the old name in the form of Rohob or Roob, stood one kilometre (1000 yards) northwest of Tel Rehov, at Khirbet Farwana/Horbat Parva and was mentioned by Eusebius as being on the fourth mile from Scythopolis, modern-day Beit She'an/Bisan.[5][7]

Archaeological work at Farwana has also exposed pottery and other finds from the Iron Age, the Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Early Islamic, Crusader, Mamluk and Ottoman periods.[34]

See also

edit- Ancient synagogues in the Palestine region - covers entire Palestine region/Land of Israel

- Ancient synagogues in Israel - covers the modern State of Israel

- Archaeology of Israel

- Cities of the ancient Near East

References

edit- ^ Avraham Negev; Shimon Gibson (July 2005). Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-8264-8571-7. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Sussmann, Jackob (1975). "כתובת מבית הכנסת של רחוב". Qadmoniot. 32 (4): 123–128.

- ^ Vitto, Fanny (1975). "בית הכנסת של רחוב". Qadmoniot. 32 (4): 119–123.

- ^ Rehob at Bible Study Tools

- ^ a b c d Mazar, Amihai (1999). "The 1997-1998 Excavations at Tel Rehov: Preliminary Report". Israel Exploration Journal. 49: 1–42. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Section R. The Pentateuch". Roōb (entry No. 766) (PDF). Translated by Wolf, C. Umhau. 1971. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b R. P. Henricus Marcellius, ed. (1837). "Liber de situ et nominibus locorum hebraicorum, [Letter R:] De pentateucho". Roob. Paris: Bibl. Ecclésiastique. p. 469. Retrieved 15 July 2019 – via "Sainte Bible expliquée et commentée, contenant le texte de la Vulgate", Appendice (1837, digitised 2010).

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ [1] Mazar, Amihai, and Israel Carmi. "Radiocarbon dates from Iron Age strata at Tel Beth Shean and Tel Rehov." Radiocarbon 43.3 (2001): 1333-1342

- ^ Bruins, Hendrik J., Johannes Van der Plicht, and Amihai Mazar. "14C dates from Tel Rehov: Iron-Age chronology, pharaohs, and Hebrew kings." Science 300.5617 (2003): 315-318.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel, and Eli Piasetzky. "Wrong and right; high and low 14C dates from Tel Rehov and Iron Age chronology." Tel Aviv 30.2 (2003): 283-295

- ^ Bruins, Hendrik J., Amihai Mazar, and Johannes van der Pflicht. The end of the 2nd millennium BCE and the transition from Iron I to Iron IIA: radiocarbon dates of Tel Rehov, Israel. Vol. 37. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2007

- ^ [2] Sergi. "Rewriting History Through Destruction: The Case of Tel Rehov and the Hebrew Bible." Writing and Re-Writing History by Destruction (2022): 18

- ^ Coldstream, Nicolas, and Amihai Mazar., "Greek Pottery from Tel Reḥov and Iron Age Chronology.", Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 53, no. 1, 2003, pp. 29–48

- ^ a b c d Noah Wiener, Tel Rehov House Associated with the Biblical Prophet Elisha, Bible and archaeology news, July 23, 2013, Biblical Archaeology Society, accessed 13 July 2019

- ^ "Oldest known archaeological example of beekeeping discovered in Israel". Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ^ a b c Ziffer, Irit, ed. (2016). It is the Land of Honey: Discoveries from Tel Rehov, the Early Days of the Israelite Monarchy (in Hebrew and English). Tel-Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum. pp. 25e–26e. OCLC 937875358.

- ^ Friedman, Matti (September 4, 2007), "Israeli archaeologists find 3,000-year-old beehives", USA Today, Retrieved 2010-01-04

- ^ Mazar, Amihai and Panitz-Cohen, Nava, (December 2007) "It Is the Land of Honey: Beekeeping at Tel Rehov" Archived 2010-07-02 at the Wayback Machine Near Eastern Archaeology, Volume 70, Number 4, ISSN 1094-2076

- ^ a b Bloch, G.; Francoy, T. M.; Wachtel, I.; Panitz-Cohen, N.; Fuchs, S.; Mazar, A. (7 June 2010). "Industrial apiculture in the Jordan valley during Biblical times with Anatolian honeybees". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (25): 11240–11244. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10711240B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003265107. PMC 2895135. PMID 20534519.

- ^ SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH, JUDY (2010-06-24). "Biblical buzz". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ^ Friedman, Matti. "Archaeologists Discover Ancient Beehives." Associated Press. 7 September 2007.

- ^ "Hebrew University excavations reveal first Biblical period beehives in 'Land of Milk and Honey'". Beth-Shean Valley Archaeological Project Tel Rehov Excavations. Hebrew University of Jerusalem Institute of Archaeology. September 2, 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-04-19.

- ^ "Tel Rehov Reveals the First Beehives in Ancient Near East." Anthropology.net. 4 September 2007. [3] Archived 2007-09-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Albright, W.F., "The Jordan Valley in the Bronze Age.", AASOR 6: 13–74, 1925–1926

- ^ Bergman (Biran), A. and Brandstater (Amiran), R., "Archaeological Trips in the Beth-Shean Valley.", Bulletin of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society 8: 85–90, 1941

- ^ Zori, N. 1962. An Archaeological Survey of the Beth Shean Valley. Pp. 135–198 in The Beth Shean Valley, The 17th Archaeological Convention. Jerusalem. (Hebrew)

- ^ Mazar, Amihai, and Nava Panitz-Cohen. "TEL REḤOV: A BRONZE AND IRON AGE CITY IN THE BETH-SHEAN VALLEY: VOLUME I: INTRODUCTIONS, SYNTHESIS AND EXCAVATIONS ON THE UPPER MOUND.", Qedem, vol. 59, 2020 ISBN 978-965-92825-2-4

- ^ Mazar, Amihai, and Nava Panitz-Cohen., "TEL REḤOV: A BRONZE AND IRON AGE CITY IN THE BETH-SHEAN VALLEY: VOLUME II: THE LOWER MOUND: AREA C AND THE APIARY.", Qedem, vol. 60, 2020 ISBN 978-965-92825-1-7

- ^ Mazar, Amihai, and Nava Panitz-Cohen., "TEL REḤOV: A BRONZE AND IRON AGE CITY IN THE BETH-SHEAN VALLEY: VOLUME III: THE LOWER MOUND: AREAS D, E, F AND G.", Qedem, vol. 61, 2020 ISBN 978-965-92825-2-4

- ^ Mazar, Amihai, and Nava Panitz-Cohen. “TEL REḤOV: A BRONZE AND IRON AGE CITY IN THE BETH-SHEAN VALLEY: VOLUME IV: POTTERY STUDIES, INSCRIPTIONS AND FIGURATIVE ART.", Qedem, vol. 62, 2020 ISBN 978-965-92825-3-1

- ^ Mazar, Amihai, and Nava Panitz-Cohen., "TEL REḤOV: A BRONZE AND IRON AGE CITY IN THE BETH-SHEAN VALLEY: VOLUME V: VARIOUS OBJECTS AND NATURAL-SCIENCE STUDIES.", Qedem, vol. 63, 2020 ISBN 978-965-92825-4-8

- ^ Mazar, Amihai. “Tel Reẖov.” Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel, vol. 119, 2007.

- ^ Golani, Amir, and Achia Kohn-Tavor., "Tel Reẖov.", Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel, vol. 117, 2005

- ^ a b c Yardenna Alexandre, 2017, Horbat Parva: Final Report, Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (HA-ESI), volume 129, year 2017, Israel Antiquities Authority, accessed 15 July 2019

- ^ a b c d Yitzhaki, Arieh [in Hebrew] (1980). "Ḥūrvat Parwah – Synagogue of 'Reḥob' (חורבת פרוה - בית-הכנסת של רחוב)". Israel Guide - Jerusalem (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 8. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. pp. 34–35. OCLC 745203905.

- ^ The permitted villages of Sebaste in the Rehov Mosaic

- ^ Jewish legal inscription from a synagogue, Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Accessed 15 July 2019.

- ^ Rachel Hachlili, "Ancient Synagogues - Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research", p. 254, BRILL, 2013. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1: The Near and Middle East, ISBN 9789004257726. Accessed 15 July 2019.

External links

edit- Tel Rehov Excavations - page includes volunteer information, preliminary reports and an image gallery.

- "The Beehives of Tel Rehov" (SourceFlix Productions) - A two-minute video clip concerning the discovery of a beehive industry at Tel Rehov, produced by an independent documentary film group, and includes a brief interview with Dr. Amihai Mazar, director of the Tel Rehov excavations.

- Yoav Vaknin, Ron Shaar, Oded Lipschits, and Erez Ben-Yosef (2022). "Reconstructing biblical military campaigns using geomagnetic field data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (44). e2209117119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11909117V. doi:10.1073/pnas.2209117119. PMC 9636932. PMID 36279453.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)