Live A Live[a] is a 1994 role-playing video game developed and published by Square for the Super Famicom. A remake was published by Square Enix in Japan and Nintendo worldwide, releasing first for Nintendo Switch in 2022, and the following year for PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, and Windows. The game follows seven distinct scenarios scattered across different time periods, with two more unlockable scenarios linking the narratives together through the recurring antagonist Odio. Gameplay is split between exploration with story-specific twists, and turn-based combat played out on a grid.

| Live A Live | |

|---|---|

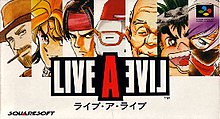

Super Famicom cover art of the seven lead characters | |

| Developer(s) | Original Square Remake Historia Square Enix |

| Publisher(s) |

|

| Director(s) | Takashi Tokita |

| Designer(s) | Nobuyuki Inoue |

| Programmer(s) | Fumiaki Fukaya |

| Artist(s) | Kiyofumi Katō Yoshihide Fujiwara Yoshinori Kobayashi Osamu Ishiwata Yumi Tamura Ryōji Minagawa Gosho Aoyama Kazuhiko Shimamoto |

| Writer(s) | Takashi Tokita Nobuyuki Inoue |

| Composer(s) | Yoko Shimomura |

| Engine | Unreal Engine 4 (Remake) |

| Platform(s) | Super Famicom Nintendo Switch PlayStation 4 PlayStation 5 Windows |

| Release | Super Famicom

|

| Genre(s) | Role-playing, turn-based tactics |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Production began in late 1993, and was the directorial debut of Takashi Tokita. Tokita wanted to tell multiple stories within a single game, with each section drawing inspiration from different sources. Character designs for the seven main scenarios were handled by different manga artists. The music was composed by Yoko Shimomura as her first large-scale project after joining Square.

Reception of the game has been positive, with praise going to its unique gameplay and narrative mechanics, though its short length was faulted. The remake was praised by Western reviewers, particularly its overall design and redone graphics and music, though several noted gameplay elements that had aged poorly. Selling 270,000 units, the original release was considered a failure, while the remake sold 500,000 copies worldwide. Tokita's work on Live A Live influenced his later projects.

Gameplay

editLive A Live is a role-playing video game in which the player takes on the role of eight different protagonists through nine scenarios.[1][2] While each narrative has the same basic mechanics, individual stories have unique gimmicks; these include the use of stealth, a lack of standard battles, or using telepathy to learn new facts to progress the narrative.[3] With the exception of one scenario, the player character navigates themed environments, ranging from the overworld area to dungeon environments.[2] Battles are triggered differently for each scenario; some are random encounters, some have enemy sprites which can be avoided, while others are entirely scripted.[2]

The turn-based battle system is used across all scenarios, and features the player character and sometimes a party fighting enemies on a 7x7 grid, with characters able to move and perform actions such as attacking or using particular skills. Skills can be used without limit, though some take multiple turns to charge.[2][4] Some abilities imbue tiles with extra properties, such as healing a character or dealing elemental damage.[2] There are also different skill systems in place; there is gaining levels with experience points, which unlocks new abilities, though in others character progression is locked behind story events. In one scenario techniques are learned through seeing an opponent use them.[2][5] Each character can also equip and use items, such as accessories to boost attack or items to recover health. If the player character, or party, is defeated, the game ends.[2]

The 2022 remake carries over the basic gameplay from the original, though redesigned and updated for the new graphical style, and with some features intended for ease of play compared to the original.[6] Bars are added representing a character's health and "charge" time before their move is executed.[7][8] Other additions include a sparkling effect over items and materials that can be gathered, a display showing a move's area of effect, and an optional radar system which shows the position of objectives on the map.[8]

Synopsis

editLive A Live is split into seven chapters, covering prehistoric, ancient Chinese, feudal Japanese, Wild West, present day, near future, and distant future eras. In each scenario, the protagonist confronts a powerful enemy whose name is or incorporates the word "Odio".[1][9] After completing these scenarios, an eighth chapter set in the Middle Ages is unlocked, which in turn unlocks a final chapter tying the narratives together.[1]

- Prehistory: The First:[10] The caveman Pogo is exiled by his tribe after rescuing and hiding Beru, a woman intended for sacrifice by a rival tribe to their dinosaur god, Odo. Pogo and Beru, having fallen in love and allied with friendly members of both tribes, successfully kill Odo and unite their tribes.

- Imperial China: The Successor:[10] The aging Shifu of the endangered Earthen Heart martial art chooses three disciples to inherit his skills. A rival school led by the ruthless Ou Di Wan Lee kills the two less experienced students. The Shifu and his surviving student defeat Ou Di Wan Lee and his students, with the Shifu sacrificing his life force to empower his surviving student. The Shifu dies after this battle, and his student begins passing down his teachings.

- Twilight of Edo Japan: The Infiltrator:[10] Trainee ninja Oboromaru is sent by his master on a mission to rescue a politically important person and kill his captor Ode Iou, a demon disguised as a daimyo intent on conquering Japan. Oboromaru defeats Ode Iou and rescues the man, who turns out to be Sakamoto Ryōma, who is helping to open Japan to the West.

- The Wild West: The Wanderer:[10] A wandering gunslinger called the Sundown Kid meets with the bounty hunter Mad Dog in an isolated town for a gun duel. The pair end up working together to liberate the town from the Crazy Bunch bandit gang, led by O. Dio. After defeating O. Dio, revealed to be a horse possessed by the dead of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the Sundown Kid leaves the town having rediscovered the value of protecting others, with his final encounters with Mad Dog varying depending on player choice.

- Present Day: The Strongest:[10] Masaru Takahara wants to become the strongest person in the world, believing that defeating opponents in each fighting style would accomplish this goal. While Masaru succeeds, he is confronted by another fighter Odie O'Bright, who has been killing his opponents because he deemed them weak. Odie O'Bright challenges Masaru, who kills him using his combined learned abilities, becoming the strongest fighter.

- The Near Future: The Outsider:[10] Psychic orphan Akira Tadokoro goes in pursuit of a biker gang called the Crusaders, seeking retribution for his father's death. Together with his friend Matsu, Akira pursues the Crusaders, learning that they are being used by the government to obtain sacrifices for an idol dubbed Odeo, which seeks to bring an enforced peace by assimilating all of humanity. Matsu−confessing that he killed Akira's father as the Crusaders' original leader−sacrifices himself trying to move the mech Steel Titan. With his powers, Akira uses the Steel Titan to destroy Odeo, ending the conspiracy.

- The Distant Future: The Mechanical Heart:[10] The cargo ship Cogito Ergo Sum is carrying a monster to Earth. Maintenance robot Cube ends up investigating the incident when the monster escapes and begins killing the crew, which, combined with fatal accidents, causes the survivors to turn on one another. The ultimate culprit is the ship's computer, OD-10, who wants to curtail the crew's recurring antisocial behavior by wiping them out. Cube hacks and deactivates OD-10, allowing the survivors and Cube to arrive to Earth after killing the monster.

- The Middle Ages: The Lord of Dark:[10] After the knight Oersted defeats his friend Streibough in a contest for the hand of Princess Alethea of Lucrece, Alethea is kidnapped by subordinates of the Lord of Dark, having apparently returned. Oersted leads a party that includes Streibough to rescue Alethea. They defeat the Lord of Dark, revealed to be a lesser monster in disguise, but Streibough is apparently killed and Alethea remains missing. Back at the castle, Oersted is tricked by a magical illusion into killing Lucrece's king, causing its people to denounce him as a demon. Escaping and with his party dead, Oersted discovers that a jealous Streibough faked his death. Oersted kills Streibough and finds Alethea, but she blames Oersted for Streibough's actions before killing herself. A despairing Oersted becomes the new Lord of Dark, taking on the name Odio.

In the final chapter, "Dominion of Hate", Odio draws the seven protagonists—Pogo, the Shifu's student, Oboromaru, the Sundown Kid, Masaru, Akira and Cube—to Lucrece to confront their heroism; the player then chooses who to play as. Choosing Oersted begins a scenario where he fights each hero using their respective Odio incarnations, either wiping out humanity and living in a world devoid of life, or obliterating the universe in a final devastating attack if he loses. Choosing any other protagonist has that character assemble and lead the party to a final battle with Odio's true form. The party can either kill Oersted, trapping them in Lucrece forever; or spare him, leading to final battles with each form of Odio, which Oersted describes as the physical incarnation of hatred. In the remake (provided the player recruited all playable characters at least once), Oersted's hate manifests into a demon called Sin of Odio that initially overwhelms the party, but Oersted breaks free with their help and destroys it. A repentant and dying Oersted sends each protagonist back to their time periods, warning them that enough hate can create another Lord of Dark.

Development

editLive A Live was developed by Development Division 5 of Square, noted as creators of the Final Fantasy series.[11] The game was the directorial debut of Takashi Tokita, who had previously worked in a designer role for Hanjuku Hero and Final Fantasy IV.[12] The original concept was born from the desire to make an RPG where players could experience multiple standalone stories at once, contrasting against Final Fantasy where smaller stories served a grand narrative arc.[12][13] The production was made possible by the expanding storage capacity of the Super Famicom ROM, with the aim being for players to be able to complete each section within a day.[14] Several staff members, including designer Nobuyuki Inoue and lead programmer Fumiaki Fukaya, had worked on either Hanjuku Hero or the Final Fantasy series.[11][15] Active production began in December 1993, though the entire development including early planning lasted one and a half years.[15] It was produced for the Super Famicom's 16-megabit cartridge.[16]

Tokita had difficulty adjusting to his role as director, particularly as he could not be as hands-on with the graphical elements as he had been for Final Fantasy IV.[17] Except for menus and battles, Fukaya was responsible for all the game's programming.[11] Tokita put an equal amount of effort into each world design.[18] Many of the world suggestions came from other members of staff, with Tokita choosing what he thought were the best.[17] The first world created was the Middle Ages edition, which informed both the wider narrative and the gameplay design.[14] The scenarios originally had a graduating difficulty scale, but Tokita abandoned this so players could tackle the scenarios in any order they wished.[17] Inoue was responsible for the battle system design, wanting to make a strategic experience which Tokita described as "real-time shogi".[11][17] Another goal was to evolve the standard gameplay of RPGs at the time.[14] One idea of Tokita's that was rejected involved not displaying hit points, but having the character physically act like they had been injured or look weakened as they took damage instead.[19] Once production finished, the team split up to work on other projects within Square.[11]

Scenario and art design

editA notable feature of Live A Live were the artists brought in to design the lead cast of the seven main sections. The artists were Yoshihide Fujiwara ("Imperial China"), Yoshinori Kobayashi ("Prehistory"), Osamu Ishiwata ("The Wild West"), Yumi Tamura ("Distant Future"), Ryōji Minagawa ("Present Day"), Gosho Aoyama ("Twilight of Edo Japan") and Kazuhiko Shimamoto ("The Near Future").[1][20] This was possible due to Square's publishing ties with Shogakukan, who was associated with those artists.[21] Additional character artwork, including designs for the "Lord of Dark" narrative, was done by Kiyofumi Katō of Square.[20][22] Further in-game graphics were designed by Yukiko Sasaki, who worked as a map designer on Final Fantasy IV.[15] Sasaki encountered difficulties with the graphics, struggling to design the Edo Japan scenario and needed to cut elements such as telegraph poles from Present Day scenario.[11] Having multiple character designers was not in the original plan, but emerged to complement the "omnibus" storytelling.[11] This style of having one artist in charge for each world was unusual for Square, who previously had a single graphic designer in charge of all art direction.[15]

Fujiwara was known for his work on the martial arts manga Kenji. For the Imperial China protagonist's female student, Fujiwara deliberately went against stereotypes of martial arts heroines with large breasts, drawing her with a "tighter" figure.[13] Shimamoto was originally going for an anime-styled design for his characters, but changed it to one based on traditional manga when he saw the other designers' work. Akira's partner Matsu was physically based on actor Yūsaku Matsuda. Ishiwata based the protagonist of the Wild West on the cowboy figures portrayed by Clint Eastwood.[23] Aoyama designed Oboromaru very quickly, and at Tokita's request based Ode Iou's design on the Japanese warlord Oda Nobunaga.[24] Tamura was in the middle of her work on Basara when she was approached about the project, and it was her only work in video game character design.[25] Katō designed the sprites of the Middle Ages cast based on templates from the Final Fantasy series, with Oersted being directly based on the Warrior of Light.[14]

The scenario was co-written by Tokita and Inoue.[9][11][26] As with his other work, Tokita drew inspiration from the tone and dramatic moments of the manga Devilman.[12] He also based its structure on Dragon Quest IV, with the script emulating the style of anime and manga.[27] The Prehistory story drew inspiration from the manga series First Human Giatrus, while the Wild West narrative was based on climactic scenes from classic Westerns including Shane. The Near Future story made several references to classic mecha manga and anime. Along with its references to classic martial arts films, the name of the protagonist in the Present Day narrative was made up of kanji symbols taken from the names of four famous wrestlers. The Distant Future narrative was inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey and Alien.[9] Cube's name, created by a member of the development staff, was a reference to Stanley Kubrick.[25] The Middle Ages story paid homage to Final Fantasy, with the relationship between Orstead and Streibough mirroring that between Cecil Harvey and Kain Highwind.[9] Tokita was concerned about creating the Middle Ages story due to its similarity to the ongoing Final Fantasy, SaGa and Mana series.[14] The final chapter and its selectable lead protagonists emulated the freedom of choice present in Romancing SaGa.[9] Inoue created the recurring gag character of Watanabe, a normal man who suffers misfortune in each era, to represent the normal people who die during each scenario.[21]

Music

editThe music was composed and arranged by Yoko Shimomura.[20] After writing music for Capcom on multiple projects including Street Fighter II, Shimomura moved to Square in 1993, fuelled by the wish to compose for RPGs.[28] Live A Live was Shimomura's first major RPG composition, and her first job after arriving at Square.[20] Her only previous work on RPGs was minor work on Breath of Fire prior to leaving Capcom.[28] As with the rest of the game, Shimomura's music reflected the different eras in which the narrative was set.[11] The main theme appeared multiple times through the score in arranged versions, an idea shared by both Shimomura and Tokita.[29] Shimomura wrote the score on a PC-9800 series, then ported it into the Super Famicom sound environment.[30]

The boss theme "Megalomania" was written to be frenetic and exciting. For the motif of Odio, Shimomura used a simulated pipe organ, incorporating it into "Megalomania" to reference its recurring threat.[29] The music for the Middle Ages period was the most difficult for Shimomura to write, though it was among the first asked for by Tokita. Upon hearing of her struggles, Final Fantasy composer Nobuo Uematsu offered to help. Writing the score for the Middle Ages became easier once the theme "Overlord Overture" and battle theme "Dignified Battle" were completed.[14] The music for the Captain Square minigame in the Distant Future scenario was deliberately written to evoke the chiptune style of NES and early arcade titles.[28]

A soundtrack album for the game was released in August 1994 by NTT Publishing.[31][32] The album was reissued on iTunes in July 2008 as one of the first releases from "Square Enix Presents Legendary Tracks", a series of rare album re-releases.[33] A physical re-release was published by Square Enix's music label in May 2012.[34]

In 2008, the tracks "Birds in the Sky, Fish in the River" and "Forgotten Wings" were included on Drammatica: The Very Best of Yoko Shimomura, a compilation of the composer's work at Square Enix.[35] Remixed and karaoke versions of "Kiss of Jealousy" and "Megalomania" were released on the 2014 compilation album Memoria, which also featured tracks from Shimomura's work with Square.[36] "Birds in the Sky, Fish in the River" and "Megalomania" were later released in 2015 as downloadable content for Theatrhythm Final Fantasy: Curtain Call.[37][38] Also that year, a tribute concert was held in Kichijoji at Club Seata, featuring performances by multiple musicians including Shimomura, and guest appearances from the game's staff including Tokita.[39]

Release

editLive A Live was released on September 2, 1994.[1] Originally meant to be released in Japan before Final Fantasy VI, delays occurred in Live A Live's production and the release order was reversed.[19] Prior to release, Tamura created a prequel manga to the Distant Future scenario, later noting that she drew the manga without Square's permission.[9] The game was re-released through Nintendo's Virtual Console for Wii U on June 17, 2015.[40] A Virtual Console port to Nintendo 3DS was released on November 28, 2016.[41] The release was prompted by fan demand for the title, and then-publisher Square Enix had to get permission from the guest illustrators before the re-release could happen.[40] Characters from Live A Live were featured in 20th anniversary crossovers with the mobile games Holy Dungeon and Final Fantasy Legends: The Space-Time Crystal.[22]

Until 2022, Live A Live remained exclusive to Japan.[21][42][43] A rumor reported by GamePro was that the title was originally planned for an English release.[43] In an interview with the magazine Super Play, Square localization staff member Ted Woolsey said that its overseas release was unlikely due to its low graphical quality compared to other popular titles at the time.[44] A fan translation was created by noted online translation group Aeon Genesis.[42] Speaking in later interviews, Tokita felt that his experience with Live A Live helped solidify his directing and storytelling.[12][45]

Remake

editOn the subject of a remake, Tokita said it would depend entirely on fan demand.[46] He later revealed that multiple attempts at a sequel or remake had fallen through over the years. After joining the Square Enix team developing Octopath Traveler, known for its "HD-2D" graphical style which blended sprite art with 3D graphics, Tokita was inspired to remake Live A Live using the graphical style of Octopath Traveler. The remake was made possible because Square Enix had been in talks over licencing from Shogakukan since the original's Virtual Console release.[21] Square Enix president Yosuke Matsuda had himself voiced a wish to remake older titles using the HD-2D design, and Live A Live was at the top of a list of proposed titles.[47]

Work on the remake began in 2019, with development proving challenging due to the COVID-19 pandemic and preserving the variety of playstyles. The remake was co-developed by Square Enix's Team Asano, and Japanese developer Historia.[21] Tokita acted as producer, while Shun Sasaki of Historia worked as director, with much of the staff being young and unrelated to the development of the original version. Sasaki expressed disbelief when approached about the remake, but accepted as many staff members were fans of Live A Live.[30] It was built using Unreal Engine.[48] The UI and sound effects were updated, and the gameplay was rebalanced.[21] It also saw gameplay additions of in-game radars and maps.[6] The character designs were redrawn by Naoki Ikushima.[21]

Shimomura returned to orchestrate and arrange the soundtrack.[21] The original MIDI sound files had been lost, so the score had to be "copied" from the original, with her feeling pressure due to the soundtrack's popularity among fans.[30] The Near Future chapter also included a vocal version of the theme "Go! Go! Buriki Daioh!", performed by Hironobu Kageyama.[6] Known for performing Dragon Ball Z opening theme "Cha-La Head-Cha-La", Kageyama also recorded an English version for the Western release.[49] The lyrics were taken from a 1994 Famitsu competition where readers sent in lyrics for the song.[6] Voice acting for main and important characters was included with the cast being chosen by Tokita based on his initial concepts for what the characters would sound like.[21] Voice actor Tomokazu Sugita, a fan of the original game, appeared in roles across all the time periods.[6]

The remake was released on July 22, 2022; Square Enix published the game in Japan, while Nintendo published it in the West. In Japan, it comes in both a physical and digital version, and a Collector's Edition from Square Enix's website. The Collector's Edition includes a model of the Buriki Daioh mech designed by Shinamoto, a themed board game, a soundtrack collection with booklet, and a shoulder bag.[50][6] A demo covering the opening chapters of the Imperial China, Edo and Far Future storylines, with progress being transferrable into the main game, was released in Japan on June 28.[51] A soundtrack album, containing the same tracks as featured in the Collector's Edition, was released in Japan on July 27.[6] Square Enix released ports for PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5 and Windows on April 27, 2023. A demo similar to the Switch version was published alongside the ports' announcement.[52]

Reception

edit| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | NS: 81/100[53] PC: 85/100[54] PS5: 84/100[55] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Eurogamer | Recommended[56] |

| Famitsu | 29/40 (SFC)[57] 33/40 (NS)[58] |

| Game Informer | 8/10[59] |

| GameSpot | 8/10[7] |

| IGN | 9/10[60] |

| Nintendo Life | 8/10[61] |

| Nintendo World Report | 7/10[62] |

| RPG Site | 8/10[8] |

The original release of Live A live sold 270,000 copies in Japan, which at the time was considered a failure compared to the company's Final Fantasy releases.[19] Tokita attributed the low sales to its release as a new project competing against entries in established series.[21] Between July and September 2022, the remake sold 500,000 copies worldwide, with over 140,000 units being sold in Japan.[63]

The four Famitsu reviewers enjoyed the game's variety, but found the graphics lacking compared to other Super Famicom titles of the time.[57] In its review, Micro Magazine's publication Game Criticism lauded the attempt at its omnibus storytelling style and use of popular manga artists, but ultimately felt it lacked substance and heavily criticized the final chapters and "imbalance" between the mature narrative and low-difficulty gameplay.[64] Retro Gamer lauded both the omnibus narrative and battle system, but felt that the title was too short; the magazine concluded that the game was a "one-of-a-kind experience"[4] Jenni Lada, writing for website GamerTell, included the title in a list of the best Super Famicom titles exclusive to Japan, praising its variety compared to other titles for the platform.[3] In 2011, GamePro included it on the list of the 14 best JRPGs that were not released in English, adding that "rumor has it the game was originally slated for a US release, making its absence here sting all the more."[43]

The remake met with a "generally favorable" reception according to review aggregator website Metacritic, earning a score of 81 points out of 100 based on 86 reviews.[53] Critics focused praise on the graphics and audio design together with the redone musical score, praising its faithful reproduction for first-time Western players and variety of settings and narratives, with complaints mainly stemming from by-then archaic mechanics carried over from the original and lack of character development in its chapters.[b]

The Famitsu reviewers were again positive, praising the remake's faithfulness to the original alongside the HD-2D conversion, with the main complaints being a lack of noticeable changes or maps for navigating levels.[58] Eurogamer's Edwin Evans-Thirlwell described the remake as "essentially Sidequest: The Game", enjoying it for the most part and noting its variety as a positive, though noting a lack of empowered female characters.[56] Andrew Reiner, writing for Game Informer, was very positive about the remake and recommended it to genre fans, with his one complaint being pacing issues with some chapters,[59] Heidi Kemps of GameSpot praised the game's subversion of genre and gaming tropes, citing it as a game that had aged well and benefited from the remake.[7]

IGN's Rebekah Valentine described the remake positively as a time capsule showing the experimental style of RPGs of the time, noting the variety within the story and battle system and extra content tied to the overarching narrative.[60] Alana Hagues, writing for Nintendo Life, enjoyed her time with the remake despite some vague directions in the latter half of the game, additionally praising the localization for convincingly mimicking accents from each time period and location.[61] Paige Chamberlain of RPG Site called the remake the best way to experience the game due to its translation and added features alongside the graphical upgrade, noting that the overall narrative was simple yet engaging and fun.[8] Nintendo World Report's Jordan Rudek was less positive than many reviewers, lauding its release in the West after so long exclusive to Japan, but finding its design archaic enough to impact his enjoyment.[62]

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e ライブ・ア・ライブ. Square Enix (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 23 March 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g ライブ・ア・ライブ 取扱説明書 [Live A Live Instruction Booklet]. Square. 2 September 1994.

- ^ a b Lada, Jenni (1 February 2008). "Important Importables: Best SNES role-playing games". Gamer Tell. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ a b Andrej, Lazarević (23 April 2010). "Live A Live". Retro Gamer. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ リメイクを望む名作『ライブ・ア・ライブ』20周年記念。本作を語れば、人はみんな1つになれる……なあ……そうだろ 松ッ!!【周年連載】. Dengeki Online (in Japanese). 1 September 2014. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g 『ライブアライブ』“リメイク発売記念生放送”本日20時より配信。時田P&下村陽子氏&ペンギンズノブオが実機プレイを披露!. Famitsu (in Japanese). 2022-05-20. Archived from the original on 2022-05-20. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- ^ a b c d Kemps, Heidi (21 July 2022). "Live A Live Review - Live, Laugh, Love Live A Live". GameSpot. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Chamberlain, Paige (21 July 2022). "Live A Live Review". RPG Site. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f ライブ・ア・ライブ〔完全攻略ガイドブック〕 [Live A Live Complete Guide] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing. October 1994. ISBN 4-8718-8331-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lada, Jenni (16 June 2022). "Live a Live Remake's Middle Ages Story Teased". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i ライブ・ア・ライブ. Game On! (in Japanese). No. 9, supplement. Shogakukan. October 1994. pp. 47–49.

- ^ a b c d Creator Talk - 時田 貴司. Gpara.com (in Japanese). 5 July 2004. Archived from the original on 10 July 2004. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b ライブ・ア・ライブ. Game On! (in Japanese). No. 4. Shogakukan. May 1994. pp. 13–15, 259.

- ^ a b c d e f 『ライブ・ア・ライブ』のリマスターはないの? ファンからの15の質問に開発陣が回答した26周年記念生放送をリポート. Famitsu (in Japanese). 4 October 2020. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d ライブ・ア・ライブ. LOGiN (in Japanese). No. 15. ASCII Corporation. August 1994.

- ^ ライブ・ア・ライブ. Game On! (in Japanese). No. 2. Shogakukan. March 1994. p. 22.

- ^ a b c d ライブ・ア・ライブ. Famitsu Tsushin (in Japanese). No. 292. ASCII Corporation. 22 July 1994. pp. 26–27.

- ^ ライブ・ア・ライブ. Famitsu Tsushin (in Japanese). No. 289. ASCII Corporation. 1 July 1994. p. 77.

- ^ a b c Szczepaniak, John (February 2018). The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers. Vol. 3. SMG Szczepaniak. pp. 198–199.

- ^ a b c d Square (25 August 1994). "Live A Live Original Sound Version booklet". (in Japanese) NTT Publishing. PSCN-5007. Retrieved on 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 『ライブアライブ』HD-2Dリメイクの新要素や変更点を時田貴司氏に訊く。何度も続編やリメイクにトライし断念、浅野チームに合流してついに実現. Famitsu (in Japanese). 10 February 2022. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b 発売20周年を迎えたオムニバスRPG「ライブ・ア・ライブ」が,Wii Uバーチャルコンソールで本日配信スタート. 4Gamer.net (in Japanese). 24 July 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ ライブ・ア・ライブ. Game On! (in Japanese). No. 3. Shogakukan. April 1994. pp. 22–24.

- ^ ライブ・ア・ライブ. Game On! (in Japanese). No. 1. Shogakukan. January 1994. pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b 祝25周年!「LIVE A LIVE A LIVE 2019 新宿編」…つづき. Yumi Tamura blog (in Japanese). 3 September 2019. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ 『ゲームプランとデザインの教科書 ~ぼくらのゲームの作り方~』出版記念 学生・若手クリエイターの為にゲームプランナーとして成功する方法教えます!!. Creative Village (in Japanese). 2018. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Square Enix (2022-08-22). 『#ライブアライブ』HD-2Dリメイクへ至る28年 プロデューサー時田貴司【#スクエニの創りかた】 (Web video). YouTube.

- ^ a b c d ゲームミュージック&アニメ専門店 ga-core - ジーエー・コア -. GA-Core (in Japanese). 2009-05-20. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2009-06-14. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b 表紙:ゲーム音楽と歩んだ25年 ~下村陽子ロングインタビュー~. 2083.jp (in Japanese). 2014. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2016-03-26. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b c 『ライブアライブ』時田P、佐々木D、楽曲監修下村陽子氏にインタビュー。「ぜひ最後のエンディングまでお楽しみください!」(時田). Famitsu (in Japanese). 22 July 2022. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Studio Midiplex - Works and Discography. Yoko Shimomura website (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ ライブ・ア・ライブ オリジナル・サウンド・ヴァージョン. NTT Publishing (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 9 March 2000. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ SFCの名作RPG『LIVE A LIVE』、サントラをiTunesでリリース. Inside Games (in Japanese). 11 July 2008. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ 【再発盤】ライブ・ア・ライブ オリジナル・サウンドトラック. Square Enix (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Drammatica: The Very Best of Yoko Shimomura". Square Enix. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ memoria! / 下村陽子25周年ベストアルバム. Square Enix (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Theatrhythm Thursday – 19/02/2015". Square Enix. 19 February 2015. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "The curtain comes down on the Theatrhythm Second Performance". Square Enix. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ あの世で、俺にわび続けろ!20周年を超え実現した『ライブ・ア・ライブ』のトーク&ライブイベント"LIVE・A・LIVE・A・LIVE 吉祥寺篇"をリポート. Famitsu (in Japanese). 2 October 2015. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b 『ライブ・ア・ライブ』がWii U用VCとして6月24日に配信決定. Dengeki Online (in Japanese). 2015-06-17. Archived from the original on 2015-06-19. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ 3DSのVCに「ライブ・ア・ライブ」など6タイトル追加 スクウェア3大悪女の一角が21世紀に降り立つ. ITMedia (in Japanese). 2016-11-28. Archived from the original on 2016-11-29. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b Lada, Jenny (5 March 2010). "Important Importables: Notable fan translation projects". Technology Tell. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ a b c "The 14 Best Unreleased JRPGs". GamePro. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011.

- ^ West, Neil (September 1994). "Fantasy Quest". Super Play. No. 23. Future Publishing. p. 17.

- ^ Hawkins, Matt (18 October 2013). "What's The Difference Between Making Final Fantasy Now And 20 Years Ago?". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Yip, Spencer (25 March 2011). "Anyone Want A Remake Of Live A Live? Well, Aside From The Game's Creator". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ スクエニ“HD-2D”リメイクをもっと活かそうと、スーパーファミコン時代のタイトルをリストアップ。その中で『ライブアライブ』が選ばれたことを明かす. Famitsu (in Japanese). 20 February 2022. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ 「ライブアライブ」28年前の作品をHD-2Dで蘇らせる挑戦 (in Japanese). Epic Games. Archived from the original on 2022-10-19. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ Torres, Josh (20 May 2022). "Live A Live introduces the eras of The Wild West, The Middle Ages, The Near Future, and Twilight of Edo Japan in new trailers". RPG Site. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Romano, Sal (9 February 2022). "Live A Live HD-2D remake announced for Switch". Gematsu. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ 『ライブアライブ』体験版配信開始!. Square Enix (in Japanese). 28 June 2022. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Vitale, Bryan (2023-03-30). "Live A Live launches for PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, and Steam on April 27". RPG Site. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ a b "Live A Live for Switch Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Live A Live for PC Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "Live A Live for PlayStation 5 Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Evans-Thirlwell, Edwin (21 July 2022). "Live A Live review - a game's worth of occasionally excellent, always intriguing JRPG side stories". Eurogamer. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b New Games Cross Review: ライブ・ア・ライブ. Famitsu Tsushin (in Japanese). No. 299. ASCII Corporation. 9 September 1994. p. 38.

- ^ a b c ライブアライブ(Switch)のレビュー・評価・感想情報. Famitsu (in Japanese). Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Reiner, Andrew (21 July 2022). "Live A Live Review - Sizzling Short Stories". Game Informer. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Valentine, Rebekah (21 July 2022). "Live A Live Review: Live Laugh Live". IGN. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Hagues, Alana (21 July 2022). "Live A Live Review (Switch)". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Rudek, Jordan (21 July 2022). "Live A Live (Switch) Review". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Romano, Sal (2 September 2022). "LIVE A LIVE remake shipments and digital sales top 500,000". Gematsu. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Saito, Keroline (1994). ゲームソフト批評Vol.2-1. Micro Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 August 2003. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

Further reading

edit- Lane, Gavin (16 July 2022). "Poll: So, How Do You Pronounce 'Live A Live'?". Nintendo Life.