Hinduism is the fourth-largest religion in Malaysia. About 1.97 million Malaysian residents (6.1% of the total population) are Hindus, according to 2020 Census of Malaysia.[2] This is up from 1.78 million (6.3% of the total population) in 2010.[3]

| |

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1.97 million (2020 est.) 1.79 million (2011 census) | |

| Religions | |

| Hinduism | |

| Languages | |

| Liturgical Old Tamil and Sanskrit Predominant Tamil Minority Telugu, Malayalam, Nepali, Bengali, Balinese, Chinese, Iban, Chitty Malay National language Bahasa Malaysia |

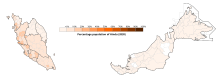

Most Malaysian Hindus are settled in western parts of Peninsular Malaysia. There are 3 states in Malaysia that qualify to be a Hindu enclave, where the Hindu percentage is greater than 10% of the population. The Malaysian state with highest percentage of Hindus, according to 2010 Census, is Negeri Sembilan (13.4%), followed by Selangor (11.6%), Perak (10.9%) and Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur (8.5%).[4] The first three mentioned technically count as being Hindu enclaves. The state with the least percentage of Hindu population is Sabah (0.1%).

Indians, along with other ethnic groups such as Chinese, began arriving in Malaysia in the ancient and medieval era. In 2010, Malaysian Census reported there were 1.91 million citizens of Indian ethnic origin.[5] About 1.64 million of Indian ethnic group Malaysians (86%) are Hindus. About 0.14 million non-Indian ethnic group Malaysian people also profess being Hindus.[6]

Malaysia gained its independence from the British colonial empire in 1957, thereafter declared its official state religion as Islam, and adopted a constitution that is mixed. On one hand, it protects freedom of religion (such as the practice of Hinduism), but on the other hand Malaysian constitution also restricts religious freedom.[7][8][9] In recent decades, there have been increasing reports of religious persecution of Hindus, along with other minority religions, by various state governments of Malaysia and its Sharia courts.[7][10] Hindu temples built on private property, and built long before Malaysian independence, have been demolished by Malaysian government officials in recent years.[11]

History

editPre Colonial era

editSimilar to the Indonesian Archipelago, the native Malays practised an indigenous animism and dynamism beliefs before the arrival of Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam. It is unclear when the first Indian voyages across the Bay of Bengal occurred. Conservative estimates place the earliest arrivals to Malay shores at least 1,700 years ago.[12] The growth of trade with India brought coastal people in much of the Malay world into contact with Hinduism. Thus, Hinduism, Indian cultural traditions and the Sanskrit language began to spread across the land. Temples were built in the Indian style and local kings began referring to themselves as Raja and more desirable aspects of Indian government were adopted.[13]

Subsequently, small Hindu Malay states started to appear in the coastal areas of the Malay Peninsula notably the Gangga Negara (2nd century), Langkasuka (2nd century), and Kedah (4th century).[14]

-

Candi Bukit Batu Pahat, an ancient Hindu temple built in 6th century A.D. found in Bujang Valley

-

Figure of a dancer carved in high relief found at Batu Lintang, south of Kedah

-

Head of Nandi found in the vicinity of site 4 near the Bujang Valley

-

One of the six stone boxes, which were found buried beneath Candi Bukit Batu Pahat

Colonial era

editMany Indian settlers came to Malaya from South India during the British colonial rule from early 19th through the mid 20th century.[15] Many came to escape poverty and famines in British India, and work as indentured labourers in initially tin mining operations and coffee, sugar plantations, and later rubber plantations; they worked with immigrant Chinese laborers on these sites.[16][17] Some English-educated Indians were appointed to more professional positions. Most were hired through British colonial labor offices in Nagapattinam or Madras (now Chennai).

In the early years, the retention rates of Hindus in Malaysia were low and with time, fewer Hindus volunteered to live in Malaysia. The colonial rule adopted a Kangani system of recruitment, where the trusted Hindu worker was encouraged and rewarded for recruiting friends and family from India to work in British operations in Malaysia.[18] The family and friends peer pressure reduced labor turnover and increased permanent migration into Malaysia. The Kangani system led to vast majority of Hindus coming from certain parts of South Indian Hindu community.[16] So concentrated was the immigration from South India, that the British colonial Malayan Administration named laws to highlight the focussed group, and enacted the Tamil Immigration Fund Ordinance in 1907.[19] A minority of Indian immigrants to Malaysia during this period came from Northern India and Sri Lanka.

The Malaysian Hindu workers during the British era were among the most marginalised. They were forced to live in closed plantation societies in frontier zones and the plantation symbolised the boundary of their existence. Racial segregation was enforced, and British anti-vagrancy laws made it illegal for Indian Hindus (and Chinese Buddhists) to enter the more developed European zoned regions. The Hindus spoke neither English nor Malay languages and remained confined to interacting within their own community.[17]

After Malaysia gained independence in 1957, local governments favored autochthonous Bumiputera and refused automatic citizenship to Indians and Chinese ethnic groups who had been living in Malaysia for decades during British colonial era.[17][20] They were declared illegal aliens and they could not apply for government jobs or own land. Sectarian riots followed, targeting Indians and Chinese, such as the 1957 Chingay riot in Penang, 1964 Malaysian racial riots, the 1967 Hartal riots, and 13 May 1969 riots.[21] Singapore, which in the early 1960s was part of Malaysia, seceded from the union and became an independent city-state. The Malaysian government passed a 1970 constitutional amendment and then the 1971 Sedition law that made it illegal to publicly discuss Malaysian citizenship methodology, national language policy, the definition of ethnic Malays as automatically Muslims, and the legitimacy of Sultans in each Malaysian state.[22]

Post Independence

editTo safeguard the interest of the Hindu organisations and Hindu temples, the Malaysia Hindu Sangam (MHS) was formed on 23 January 1965.[23] Among the great contribution of MHS towards the upliftment of Hindus in Malaysia was the Gurukal training programme in the 1980s to train local young men as temple priests.[24]

Samadhis of Siddhas

editSiddhas have traveled to then Malaya and performed austerities and eventually went into Jeeva Samadhi. Jeganatha Swamigal, a disciple of Ramalinga Adigal, was the foremost among a handful of saints who ventured to the then Malaya. Jeganatha Swamigal's Samadhi is located at Tapah, Perak.[25] Presently, the Jeganatha Swamigal's Samadhi and the land adjacent to its temple is managed by Malaysia Hindu Sangam. A new temple enshrining the image of Sri Jeganathar Swami is being erected.[26]

Other popular Samadhi is of Sannasi Andavar in Cheng, Malacca and Mauna Swamigal in the vicinity of Lord Saturn's temple at Batu Caves.[27]

Culture

editWorship and deities

editMalaysian Hinduism is diverse, with large urban temples dedicated to specific deities, and smaller temples located on estates. The estate temples generally follow the tradition of the Indian region from which the temples' worshippers originate. Many people follow the Shaivite, or Saivite, tradition (worship of Shiva), of Southern India.[28] However, there are also some Vaishnava Hindus in Malaysia as well, many of them of North Indian extraction, and these Hindus worship in temples such as the Geeta Ashram in Seksyen 52, Petaling Jaya, or the Lakshmi-Narayana Temple in Kampung Kasipillay, Kuala Lumpur. Services in these temples are usually conducted in Tamil and English.

Folk Hinduism is the most prevalent variety, including spiritualism and worship of village deities.[29]

Temples and religious bodies

editThe International Society for Krishna Consciousness also has a number of followers in Malaysia, and maintains temples in Kuala Lumpur and also all over Malaysia.[30] The Ratha-Yatra festival is held once a year in every temple throughout Malaysia approximately 10 to 12 Ratha Yatra which will be held usually end of the Year, when the Deities of Lord Jagannatha, Baladeva and Subhadra are placed on a chariot which is pulled through the streets by devotees, accompanied by a party chanting the Hare Krishna Mahamantra.[31] There also another group of Hare Krishna such as (followers of Ritvik, followers of Hansa Duta). There is also Gaudiya math and Saraswath Math.[32]

There are also few devotees of Sri Vaishnavism of Ramanujacharya and the Madhvacharya Sampradaya.[33]

Malaysia also has large followers of several Vedantic traditions and groups such as Ramakrishna Mission. Ramakrishna Mission in Petaling Jaya has been in existence since the 1940s and was officially affiliated to the Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission, India in 2001. In 2015, the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi visited the Ramakrishna Mission and unveiled a statue of Swami Vivekananda. Another important centre, closely connected with the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda movement is the Ramakrishna Ashramam, Penang which came into existence in 1938. The Vivekananda Ashrama, Kuala Lumpur is an institution started by the Jaffna (Sri Lankan) Tamil immigrants in 1904 in honour of Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902). The building, constructed in 1908, is dedicated to his work in providing education and spiritual development for the youth and community.[34] The Vivekananda Ashram with a bronze statue of Swami Vivekananda has been declared as a heritage site in 2016.[35]

Other popular Vedanta-based organisations in Malaysia are Divine Life Society (also called Shivananda Ashram) with its headquarters at Batu Caves and Arsha Vijnana Gurukulam.[36]

Since the Second World War a revival of Hinduism has occurred among Indian Malaysians, with the foundation of organisations and councils to bring unity or to promote reform.[37][38]

-

Nagarathar Sivan Temple, George Town.

Hindu religious festivals

editSome of the major Hindu festivals celebrated every year include Deepavali (festival of lights), Thaipusam (Lord Murugan festival), Pongal (harvest festival) and Navaratri (Durga festival).[39]

Deepavali is the primary Hindu festival in Malaysia. The Malaysian Hindus traditionally hold open houses over Deepavali, where people of different ethnic groups and religions are welcomed in Hindu homes to share the festival of light as well as taste Indian food and sweets.[40]

Deepavali and Thaipusam are Public holidays in all states on Malaysia, except Sarawak.[41]

The Malayalees celebrate Vishu, the Malayalee New Year which usually falls in the month of April or the month of Medam in the Malayalam calendar. Onam is the most popular festival celebrated by the Malayalee community and is usually observed in the month of August or September. They usually prepare Sadhya, a lunch feast consisting 16 to 24 vegetarian dishes (without onions and garlics).

Distribution of Hindus

editDistribution of Hindu Malaysians by ethnic group (2010 census)

According to the 2010 Census, there were 1,777,694 people self-identifying as Hindus (6.27% of the population). Of the Hindus, 1,644,072 were Indian, 111,329 were non-citizens, 14,878 were Chinese, 4,474 Others, and 2,941 Tribals (Including 554 Iban in Sarawak).[42] 92.48% of all the Indian Malaysians were Hindu. Information collected in the census based on the respondent's answer and did not refer to any official document.

There is a small historic Chitty community in Malacca, who are also known as the Indian Peranakans. They have adopted Chinese and Malay cultural practices whilst also retaining their Hindu heritage.[43]

The Total fertility rate per religion is not published by the Malaysian government, only fertility rate by ethnicity is published. The fertility rate of Indians was 1.7 in 2010 which has fallen to 1.3 in 2016.[44]

By gender and ethnic group

edit| Gender | Total Hindus Population (2010 Census) |

Hindu Malaysian Citizens | Hindu non-Malaysians | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bumiputera Hindus | Non-Bumiputera Hindus | ||||||

| Malay Hindus | Other Bumiputera Hindus | Chinese Hindus | Indian Hindus | Others Hindus | |||

| Nationwide | 1,777,694 | 0 | 2,941 | 14,878 | 1,644,072 | 4,474 | 111,329 |

| Male Hindus | 921,154 | 0 | 1,524 | 7,638 | 821,995 | 2,402 | 87,595 |

| Female Hindus | 856,540 | 0 | 1,417 | 7,240 | 822,077 | 2,072 | 23,724 |

There are 6300 Balinese people in Malaysia, 90% of whom are Hindus.[45] The 'Other Hindus' in the above Table might be representing them.

By state or federal territory

edit| State | Total Hindus population (2010 Census) |

% of State Population |

|---|---|---|

| Johor | 221,128 | 6.6% |

| Kedah | 130,958 | 6.7% |

| Kelantan | 3,670 | 0.2% |

| Kuala Lumpur | 142,130 | 8.5% |

| Labuan | 357 | 0.4% |

| Malacca | 46,717 | 5.7% |

| Negeri Sembilan | 136,859 | 13.4% |

| Pahang | 60,428 | 4.0% |

| Penang | 135,887 | 8.7% |

| Perak | 255,337 | 10.9% |

| Perlis | 1,940 | 0.8% |

| Putrajaya | 708 | 1.0% |

| Sabah | 3,037 | 0.1% |

| Sarawak | 4,049 | 0.2% |

| Selangor | 1,231,980 | 18.6% |

| Terengganu | 2,509 | 0.2% |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1961 | 749,831 | — |

| 1971 | 843,982 | +12.6% |

| 1981 | 920,400 | +9.1% |

| 1991 | 1,112,300 | +20.8% |

| 2001 | 1,380,400 | +24.1% |

| 2011 | 1,777,694 | +28.8% |

| 2021 | 1,979,290 | +11.3% |

Historical population

editThe percentage of the Hindus in Malaysia has decreased very much in the past 6 decades, mainly after the Independence of Malaya due to the Islamic fundamentalism policies by Government and other reasons.[46] There has many rules favouring the Muslims and the rights of Hindus and other minority are neglected by the Sharia courts. There has been also reports of high numbers of Malaysian Hindus of converting to Christianity and Islam. Many Hindu groups reported that nearly 160,000 Hindus have converted to Christianity and Islam, out of which 130,000 converted to Christianity and 30,000 to Islam (till 1991) and most of them were Singaporean and Malaysian Tamils.[47]

| Hindus %age over the time[48] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Years | Hindu population | Total population | Hindus (%) |

| 1961 | 749,831 | 8,378,500 | 8.94% |

| 1971 | 843,982 | 11,159,700 | 7.56% |

| 1981 | 920,400 | 14,256,900 | 6.45% |

| 1991 | 1,112,300 | 18,547,200 | 5.99% |

| 2001 | 1,380,400 | 24,030,500 | 5.74% |

| 2011 | 1,777,694 | 28,588,600 | 6.3% |

| 2021 | 1,979,290 | 32,447,400 | 6.1% |

Persecution of Hindus

editDerogatory terms

editPeople of Indian descent are derogatory called "Keling" in Malaysia.[49]

Islamic preferentionalism

editIslam is the official religion of Malaysia. The Constitution of Malaysia declares that Islam is the only religion of true Malay people and that natives are required to be Muslims.[50] Conversion from Islam to Hinduism (or another religion) is against the law, but the conversion of Hindus, Buddhists, and Christians to Islam is welcomed. The government actively promotes the spread of Islam in the country.[8] The law requires that any Hindu (or Buddhist or Christian) who marries a Muslim must first convert to Islam, otherwise the marriage is illegal and void.[8] If one of the Hindu parents adopts Islam, the children automatically become Muslim without the consent of the second parent.[7][51]

There are numerous cases in Malaysian courts relating to official persecution of Hindus. For example, in August 2010, a Malaysian woman named Siti Hasnah Banggarma was denied the right to convert to Hinduism by a Malaysian court; Banggarma, who was born a Hindu, but was forcibly converted to Islam at age 7, desired to reconvert back to Hinduism and appealed to the courts to recognise her reconversion. The appeal was denied.[52]

Destruction of Hindu temples

editAfter a violent conflict in Penang between Hindus and Muslims in March 1998, the government announced a nationwide review of unlicensed Hindu temples and shrines. However, implementation was not vigorous and the program was not a subject of public debate.[53]

On 21 April 2006, the Malaimel Sri Selva Kaliamman Temple in Kuala Lumpur was reduced to rubble after the city hall sent in bulldozers.[54]

The growing Islamization in Malaysia is a cause for concern to many Malaysians who follow minority religions such as Hinduism.[55]

On 11 May 2006, armed city hall officers from Kuala Lumpur forcefully demolished part of a 90-year-old suburban temple that serves more than 3,000 Hindus. The Hindu Rights Action Force (HINDRAF), a coalition of several NGOs, have protested these demolitions by lodging complaints with the Malaysian Prime Minister.[56]

HINDRAF chairman, Waytha Moorthy Ponnusamy, said:

...These state atrocities are committed against the most underprivileged and powerless sector of the Hindu society in Malaysia. We appeal that this Hindu temple and all other Hindu temples in Malaysia are not indiscriminately and unlawfully demolished.[56]

Many Hindu advocacy groups have protested what they allege is a systematic plan of temple cleansing in Malaysia. The official reason given by the Government of Malaysia has been that the temples were built "illegally". However, several of the temples are centuries old.[56]

According to a lawyer for HINDRAF, a Hindu temple is demolished in Malaysia once every three weeks.[57]

In 2007, Malaysian Hindu organisations protested the destruction of Hindu temples by the Malaysian regime. On 30 October 2007, the 100-year-old Maha Mariamman Temple in Padang Jawa was demolished by Malaysian authorities. Following that demolition, Works Minister and head of the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC) Samy Vellu, who is of Indian origin, said that Hindu temples built on government land were still being demolished despite his appeals to the various state chief ministers.

Such temple destructions in Malaysia have been reported by the Hindu American Foundation (HAF).[58]

HAF notes that the Malaysian government had restricted the right for 'Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Association' contrary to Article 20 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and Article 10 of the Malaysian Federal Constitution, and that the application filed by Malaysian Hindus to hold gatherings have been arbitrarily denied by the police. The Government has also tried to suppress a campaign launched by the HINDRAF to obtain 100,000 signatures in support of a civil suit against the Government of United Kingdom.[58] HINDRAF has accused the Malaysian government of intimidating and instilling fear in the Indian community.[59]

The 2007 HINDRAF rally prompted the Malaysian government to open dialogue with various Indian and Hindu organizations like the Malaysia Hindu Council, Malaysia Hindudharma Mamandram, and Malaysian Indian Youth Council (MIYC) to address the misgivings of the Indian community.[60] HINDRAF itself has been excluded from these talks and no significant changes have resulted from the discussions.[61]

Cow head debacle

editThe Cow head protests was a protest that was held in front of the Selangor state government headquarters at the Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah Building, Shah Alam, Malaysia on 28 August 2009. The protest was called so because the act of a few participants who brought along a cow head, which they later "stomped on the head and spat on it before leaving the site".[62] The cow is considered a sacred animal to Hindus.

The protest was held due to Selangor state government's intention to relocate a Hindu temple from Section 19 residential area of Shah Alam to Section 23. The protesters were mainly Muslim extremists who opposed the relocation due to the fact that Section 23 was a Muslim majority area.

The protest leaders were also recorded saying there would be blood if a temple was constructed in Shah Alam.[63] The protest was caught on video by the popular Malaysian online news portal Malaysiakini.[64]

Revathi Massosai religion conversion case

editRevathi Massosai, who was born to Muslim parents but raised as a Hindu, married a Hindu man in 2004. But her marriage is not recognised by the Malaysian government because a Hindu man can't marry a Muslim girl as per the Sharia law. She was incarcerated for six months in an Islamic re-education camp because of her attempts to renounce Islam in favour of the Hindu religion, where she was forced to eat beef (which some Hindus refuse on religious grounds), forced to pray as a Muslim and to wear a headscarf. Islamic officials took the couple's 18-month-old daughter away from Suresh (her Hindu father) and gave her to Revathi's mother (her Muslim grandmother). Officials have ordered Revathi to live with her mother and continue with her Islamic 'counseling'.[65][66]

Fatwa against Yoga

editIn 2008, The National Fatwa Council of Malaysia issued a fatwa against Yoga. Abdul Shukor Husim, the council's chairman, said: "We are of the view that yoga, which originates in Hinduism, combines a physical exercise, religious elements, chanting and worshipping for the purpose of achieving inner peace and ultimately to be at one with God. For us, yoga destroys a Muslim's faith".[67][68][69]

Indira Gandhi conversion case

editIn 2009, Indira Gandhi's husband Pathmanathan converted to Islam and took up the name Muhammad Riduan Abdullah. Then he unilaterally converted his three children (one of whom was 11 months old) to Islam without the consent of his wife. The Sharia Court also granted custody of children to Riduan.[70]

The Federal Court on 2016 had ordered the Inspector-General of Police to execute a warrant of arrest for Riduan. Karan and Tevi have declared themselves Hindus. However, Riduan escaped taking Prasana along with him, both of them are still not found.[71][72][73][74]

Activism and politics

editHindu Rights Action Force, better known by its acronym HINDRAF is a Hindu-activism non-governmental organisation (NGO). This organisation began as a coalition of 30 Hindu NGOs committed to the preservation of Hindu community rights and heritage in a multiracial Malaysia.[75][76]

HINDRAF has had a major impact on the political landscape of Malaysia by staging the infamous 2007 HINDRAF rally. Following an enormous rally organised by HINDRAF in November 2007, several prominent members of the organisation were arrested, some on charges of sedition. The charges were dismissed by the courts. Five people were arrested and detained without trial under the Internal Security Act (ISA).[77] Toward the end of the 2000s, the group developed a broader political program to preserve and to push for equal rights and opportunities for the minority Indians. It has been successful in continuing to focus attention on the racist aspects of Malaysian Government policies.[78]

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ "Malaysia Demographics Profile". 27 November 2020.

- ^ 2010 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia (Census 2010) Archived 14 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine Department of Statistics Malaysia, Official Portal (2012)

- ^ Saw, Swee-Hock (2007). The Population of Malaysia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812304438.

- ^ Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristics 2010 Archived 11 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Department of Statistics, Government of Malaysia (2011), Page 13

- ^ "Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristics 2010" (PDF). Department of Statistics. Government of Malaysia. 2011. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012.

- ^ Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristics 2010 Archived 11 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Department of Statistics, Government of Malaysia (2011), Page 82

- ^ a b c Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom – Malaysia". Refworld. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Gill, Savinder Kaur; Gopal, Nirmala Devi (1 October 2010). "Understanding Indian Religious Practice in Malaysia". Journal of Social Sciences. 25 (1–3): 135–146. doi:10.1080/09718923.2010.11892872. ISSN 0971-8923. S2CID 30276441.

- ^ Raymond Lee, Patterns of Religious Tension in Malaysia, Asian Survey, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Apr., 1988), pp. 400-418

- ^ Religious Freedom Report 2013 – Malaysia U.S. State Department (2014)

- ^ Religious Freedom Report 2012 – Malaysia U.S. State Department (2013)

- ^ Barbara Watson Andaya, Leonard Y. Andaya (1984). A History of Malaysia. Lonndon: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 14. ISBN 0-333-27672-8.

- ^ Zaki Ragman (2003). Gateway to Malay culture. Singapore: Asiapac Books Pte Ltd. pp. 1–6. ISBN 981-229-326-4.

- ^ "Early Malay kingdoms". Sabrizain.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ Sandhu (2010), Indians in Malaya: Some Aspects of Their Immigration and Settlement (1786–1957), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521148139

- ^ a b Amarjit Kaur, Indian migrant workers in Malaysia – part 1 Australian National University

- ^ a b c "Indian migrant workers in Malaysia – part 2". New Mandala. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Sandhu (2010), Indians in Malaya: Some Aspects of Their Immigration and Settlement (1786–1957), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521148139, pp. 89–102

- ^ Sandhu (2010), Indians in Malaya: Some Aspects of Their Immigration and Settlement (1786–1957), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521148139, pp. 60–68

- ^ "Malaysian Indian Hindu community: Victims of Bhumipatera policy" (PDF). ORF Online. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Evans, Carolyn (2004). "Human Rights Commissions and Religious Conflict in the Asia-Pacific Region". The International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 53 (3): 713–729. doi:10.1093/iclq/53.3.713. ISSN 0020-5893. JSTOR 3663296.

- ^ Peletz, Michael (2020l). Islamic Modern: Religious Courts and Cultural Politics in Malaysia. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09508-0. JSTOR 40005950.

- ^ "Malaysia Hindu Sangam – மலேசிய இந்து சங்கம் (Company No.5859-M)". Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Ramanathan 2008.

- ^ Lee & Rajoo 1987, p. 34.

- ^ Collins 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Collins 1997, p. 7.

- ^ "Malaysian Culture – Religion". Cultural Atlas. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Lee & Rajoo 1987, p. 17.

- ^ "Malaysia – ISKCON Centres". Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "ISKCON Malaysia – International Society for Krishna Consciousness in Kuala Lumpur". MALAYSIA CENTRAL (ID). 6 June 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Collins 1997, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Staff 2015.

- ^ "Our History | The Vivekananda Ashrama Kuala Lumpur". Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ M, BAVANI. "112-year-old Vivekananda Ashram is now a heritage site". The Star. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Anwar, Asif (19 December 2018). "9 Stunning Hindu Temples In Malaysia You Must Visit Soon". Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ LEE, RAYMOND L.M. (1986). "The Ethnic Implications of Contemporary Religious Movements and Organizations in Malaysia". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 8 (1): 70–87. doi:10.1355/CS8-1E. ISSN 0129-797X. JSTOR 25797883.

- ^ "Malaysia: Majority Supremacy and Ethnic Tensions | IPCS". www.ipcs.org. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Tan 2018, pp. 167–178; Collins 1997, pp. 46–50.

- ^ "Hinduism in Malaysia". Hindu Dharma Mamandram. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Malaysia Public Holidays 2018". PublicHolidays.com.my. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Taburan Penduduk dan Ciri-ciri Asas Demografi" [2010 Malaysian Population and Demography Census] (PDF). Statistics.gov (in Malay). Government of Malaysia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Meet the Chetti Melaka, or Peranakan Indians, striving to save their vanishing culture". CNA. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ DOSM

- ^ Project, Joshua. "Balinese in Malaysia". joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Protect Hindus in Malaysia: BJP". Hindustan Times. 6 December 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "160,000 Convert Out of Hinduism in Malaysia". Hinduism Today. 1 February 1992. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Department of Statistics Malaysia". www.dosm.gov.my. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ M. Veera Pandiyan (10 August 2016). "'Keling' and proud of it". The Star online.

- ^ Sophie Lemiere, apostasy & Islamic Civil society in Malaysia, ISIM Review, Vol. 20, Autumn 2007, pp. 46–47

- ^ Press, Oxford University (1 May 2010). "20". Islamic Criminal Law: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide. Oxford University Press, United States. pp. 357–379. ISBN 978-0-19-980386-6.

- ^ "US-based HAF calls Banggarma verdict 'religiously discriminatory'". Archived from the original on 6 August 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ Annual Report on International Religious Freedom. USCIRF. 2001. p. 178.

- ^ "Malaysia demolishes century-old Hindu temple". Daily News and Analysis. 21 April 2006. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ "Pressure on multi-faith Malaysia". 16 May 2006. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "Business News: Business News India, Business News Today, Latest Finance News, Business News Live". The Financial Express. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Malaysia ethnic Indians in uphill fight on religion Archived 23 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine Reuters India – 8 November 2007

- ^ a b "HAF condemns Malaysia temple demolision". HAF. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ HINDRAF home

- ^ NGOs discuss Indian issues with PM in heart-to-heart chat Archived 5 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Star – 15 December 2007

- ^ "Protect Hindus in Malaysia: BJP". Hindustan Times. 6 December 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Malaysian Muslims protest against proposed construction of Hindu temple". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. 29 August 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Malaysia Muslims protest proposed Hindu temple Associated Press – 28 August 2009

- ^ Temple demo: Residents march with cow's head YouTube. 28 August 2009

- ^ "Malaysia 'convert' claims cruelty". 6 July 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Muslim-Born Woman in Malaysia Wants to Live as a Hindu: Denied". www.digitaljournal.com. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Malaysia bans Muslims from practicing yoga". The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Islamic ruling bans Malaysia's Muslims from practising yoga". the Guardian. 24 November 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Reuters Staff (26 November 2008). "Malaysia backs down from yoga ban amid backlash". Reuters. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Hamdan, Nurbaiti Hanim Binti. "Indira Gandhi files RM100mil lawsuit". The Star. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Indira Gandhi: Grateful for decision, but where is my daughter? | The Star". www.thestar.com.my. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Lim, Ida (February 2018). "Simplified: The Federal Court's groundbreaking Indira Gandhi judgment | Malay Mail". www.malaymail.com. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Bunyan, John (31 January 2018). "Indira Gandhi refuses to forgive ex-husband after nine-year court battle | Malay Mail". www.malaymail.com. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "No more excuses, find my daughter, Indira Gandhi tells police | The Malaysian Insight". www.themalaysianinsight.com. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Hindu group protests "temple cleansing" in Malaysia Archived 4 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Southeast Asia news and business from Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 15 January 2006. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Five Hindraf leaders detained under ISA (final update)". The Star Online. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ "Malaysia's Anwar condemns use of security law". Reuters. 14 December 2007.

Bibliography

edit- Belle, Carl Vadivella (13 May 2016). Tragic Orphans. Flipside Digital Content Company Inc. ISBN 978-981-4620-95-6.

- Lee, Raymond L. M.; Rajoo, R. (1987). "Sanskritization and Indian Ethnicity in Malaysia". Modern Asian Studies. 21 (2): 389–415. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0001386X. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 312653. S2CID 145117285.

- Belle, Carl Vadivella (13 February 2017). Thaipusam in Malaysia: A Hindu Festival in the Tamil Diaspora. ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. ISBN 978-981-4695-75-6.

- Aljunied, Khairudin (2019). Islam in Malaysia: An Entwined History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-092519-2.

- Tan, Chee-Beng (12 February 2018). Chinese Religion in Malaysia: Temples and Communities. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-35787-7.

- Collins, Elizabeth Fuller (1997). Pierced by Murugan's Lance: Ritual, Power, and Moral Redemption Among Malaysian Hindus. Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-87580-223-7.

- Ramanathan, K. (2 January 2008). "Hinduism in a Muslim state: The case of Malaysia". Asian Journal of Political Science. 4 (2): 42–62. doi:10.1080/02185379608434083.

Further reading

edit- Staff, IndiaFacts (8 September 2015). "The Stateless Hindus of Malaysia: A Whitepaper". IndiaFacts.

- "Malaysia's clash of cultures". BBC News.

- Ktemoc (20 March 2006). "KTemoc Konsiders ........: DBKL smashed statues of Hindu gods!". KTemoc Konsiders ........ Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- "100 years old temple razed in Malaysia". News18.

- "Video of demolision of Hindu temple in Malaysia". Malaysia Kini TV. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006.

- "New religious dispute sparks fears of rising Islamization in Malaysia". Archived from the original on 16 December 2007.

- "Malaysia 'convert' claims cruelty". BBC News. 6 July 2007.

- "Malaysia Hindu activists arrested". BBC News. 23 November 2007.

- "Malaysia Hindu activists released". BBC News. 26 November 2007.

- "Detentions over Malaysian Hindu rally". CNN.

- "Malaysia burial row fuels tension". BBC News. 26 June 2008.

- "Protesters threaten bloodshed over Hindu temple". The Malaysian Insider. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009.

- "Crisis in Malaysia: On Mahathir Mohamad resignation". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X.