Dakar (/dɑːˈkɑːr, dæ-/ UK also: /ˈdækɑːr/;[4] French: [dakaʁ]; Wolof: Ndakaaru)[5] is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 million in 2023.

Dakar | |

|---|---|

City of Dakar, divided into 19 communes d'arrondissement | |

| Coordinates: 14°41′34″N 17°26′48″W / 14.69278°N 17.44667°W | |

| Country | |

| Région | Dakar |

| Département | Dakar |

| Settled | 15th century |

| Communes d'arrondissement | 19

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Barthélemy Dias (YAW/MTS) |

| Area | |

| 79.83 km2 (30.82 sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 535 km2 (207 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 22 m (72 ft) |

| Population (2023 Census)[3] | |

| 1,278,469 | |

| • Density | 16,000/km2 (41,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,004,427[1] |

| • Metro density | 7,485/km2 (19,390/sq mi) |

| Data here are for the administrative Dakar région, which matches almost exactly the limits of the metropolitan area | |

| Time zone | UTC+00:00 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | (Not Observed) |

| Website | villededakar.sn |

Dakar is situated on the Cap-Vert peninsula, the westernmost point of mainland Africa.[6] Cap-Vert was colonized by the Portuguese in the early 15th century. The Portuguese established a presence on the island of Gorée off the coast of Cap-Vert and used it as a base for the Atlantic slave trade. France took over the island in 1677. Following the abolition of the slave trade and French annexation of the mainland area in the 19th century, Dakar grew into a major regional port and a major city of the French colonial empire. In 1902, Dakar replaced Saint-Louis as the capital of French West Africa. From 1959 to 1960, Dakar was the capital of the short-lived Mali Federation. In 1960, it became the capital of the independent Republic of Senegal. Dakar will host the 2026 Summer Youth Olympics.

History

editThe Cap-Vert peninsula was settled no later than the 15th century, by the Lebu people, an aquacultural subgroup of the Wolof ethnic group. The original villages—Ouakam, Ngor, Yoff and Hann—still constitute distinctively Lebou neighborhoods of the city today. In 1444, the Portuguese reached the Bay of Dakar.[7][8][9] Peaceful contact was finally opened in 1456 by Diogo Gomes, and the bay was subsequently referred to as the "Angra de Bezeguiche" (after the name of the local ruler).[10] The bay of "Bezeguiche" would go on to serve as a critical stop for the Portuguese India Armadas of the early 16th century, where large fleets would routinely stop, both on their outward and return journeys from India, to repair, collect fresh water from the rivulets and wells along the Cap-Vert shore and trade for provisions with the local people for their remaining voyage.[10] (It was famously during one of these stops, in 1501, where the Florentine navigator Amerigo Vespucci began to construct his "New World" hypothesis about America.[11])

The Portuguese eventually founded a settlement on the island of Gorée (then known as the island of Bezeguiche or Palma), which by 1536 they began to use as a base for slave exportation. The mainland of Cap-Vert, however, was under control of the Jolof Empire, as part of the western province of Cayor which seceded from Jolof in its own right in 1549. A new Lebou village, called Ndakaaru, was established directly across from Gorée in the 17th century to service the European trading factory with food and drinking water. Gorée was captured by the United Netherlands in 1588, which gave it its present name (spelled Goeree, after Goeree-Overflakkee in the Netherlands).[citation needed] The island was to switch hands between the Portuguese and Dutch several more times before falling to the English under Admiral Robert Holmes on January 23, 1664, and finally to the French in 1677. Though under continuous French administration since, métis families, descended from Dutch and French traders and African wives, dominated the slave trade. The infamous "House of Slaves" was built at Gorée in 1776.

In 1795, the Lebou of Cape Verde revolted against Cayor rule. A new theocratic state, subsequently called the "Lebou Republic" by the French, was established under the leadership of the Diop, a Muslim clerical family originally from Koki in Cayor. The capital of the republic was established at Ndakaaru. In 1857, the French established a military post at Ndakaaru (which they called "Dakar") and annexed the Lebou Republic, though its institutions continued to function nominally. The Serigne (also spelled Sëriñ, "Lord") of Ndakaaru is still recognized as the traditional political authority of the Lebou by the Senegalese State today.[citation needed]

The slave trade was abolished by France in February 1794. However, Napoleon Bonaparte reinstated the slave trade in May 1802. The slave trade continued at Gorée until 1848, when it was finally abolished throughout all French territories. To replace trade in slaves, the French promoted peanut cultivation on the mainland. As the peanut trade boomed, tiny Gorée Island, whose population had grown to 6,000 residents, proved ineffectual as a port. Traders from Gorée decided to move to the mainland and a "factory" with warehouses was established in Rufisque in 1840.[citation needed]

Large public expenditure for infrastructure was allocated by the colonial authorities to Dakar's development. The port facilities were improved with jetties, a telegraph line was established along the coast to Saint-Louis and the Dakar-Saint-Louis railway was completed in 1885, at which point the city became an important base for the conquest of the Western Sudan.

Gorée, including Dakar, was recognised as a French commune in 1872. Dakar itself was split off from Gorée as a separate commune in 1887. The citizens of the city elected their own mayor and municipal council, and helped send an elected representative to the National Assembly in Paris. Dakar replaced Saint-Louis as the capital of French West Africa in 1902.[12] A second major railroad, the Dakar-Niger built from 1906 to 1923, linked Dakar to Bamako and consolidated the city's position at the head of France's West African empire.[citation needed] In 1929, the commune of Gorée Island, now with only a few hundred inhabitants, was merged into Dakar.

Urbanization during the colonial period was marked by forms of racial and social segregation—often expressed in terms of health and hygiene—which continue to structure the city today. Following a plague epidemic in 1914, the authorities forced most of the African population out of old neighborhoods, or "Plateau", and into a new quarter, called Médina, separated from it by a "sanitary cordon". As first occupants of the land, the Lebou inhabitants of the city successfully resisted this expropriation. They were supported by Blaise Diagne, the first African to be elected Deputy to the National Assembly. Nonetheless, the Plateau thereafter became an administrative, commercial, and residential district increasingly reserved for Europeans and served as model for similar exclusionary administrative enclaves in French Africa's other colonial capitals (Bamako, Conakry, Abidjan, Brazzaville). Meanwhile, the Layene Sufi order, established by Seydina Mouhammadou Limamou Laye, was thriving among the Lebou in Yoff and in a new village called Cambérène. Since independence, urbanization has sprawled eastward past Pikine, a commuter suburb whose population (2001 est. 1,200,000) is greater than that of Dakar proper, to Rufisque, creating a conurbation of almost 3 million (over a quarter of the national population).[citation needed]

In its colonial heyday Dakar was one of the major cities of the French Empire, comparable to Hanoi or Beirut.[citation needed] French trading firms established branch offices there and industrial investments (mills, breweries, refineries, canneries) were attracted by its port and rail facilities. It was also strategically important to France, which maintained an important naval base and coaling station in its harbor, and which integrated it into its earliest air force and airmail circuits, most notably with the legendary Mermoz airfield (no longer extant).

In 1940, Dakar became involved in the Second World War when General de Gaulle, leader of the Free French Forces, sought to make the city the base of his resistance operations. The object was to raise the Free French flag in West Africa, to occupy Dakar and thus start to consolidate the French resistance of its colonies in Africa. The plan had British naval support when fighting alone against the Axis powers. However, due to delays and the plan becoming known, Dakar had already come under the influence of the German controlled will of the Vichy government. With the arrival of French naval forces under Vichy control and faced by stubborn defences onshore, de Gaulle's proposals were resisted, and the Battle of Dakar ensued off the coast lasting three days 23-25 September 1940, between the Vichy defences and the attack of the Free French and British navy. The enterprise was abandoned after appreciable naval losses. Although the initiative on Dakar failed, General de Gaulle was able to establish himself at Douala in the Cameroons which became the rallying point for the resistance of the Free French cause.[13][14][15]

In November 1944, West African conscripts in the French army mutinied against poor conditions at the Thiaroye camp, on the outskirts of the city. The mutiny was seen as an indictment of the colonial system and constituted a watershed for the nationalist movement. On 1 December 1944, French soldiers guarding the camp opened fire on the West African soldiers. Accounts of the death toll range from around 35 (the official French account) to over 300 (army veterans active at the time).

Dakar was the capital of the short-lived Mali Federation from 1959 to 1960, after which it became the capital of Senegal. The poet, philosopher and first President of Senegal Léopold Sédar Senghor tried to transform Dakar into the "Sub-Saharan African Athens" (l'Athènes de l'Afrique subsaharienne),[16] as his vision was for it.

Dakar is a major financial centre, home to a dozen national and regional banks (including the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) which manages the unified West African CFA franc currency), and to numerous international organizations, NGOs and international research centers. Dakar has a large Lebanese community (concentrated in the import-export sector) that dates to the 1920s, a community of Moroccan businesspeople, as well as Mauritanian, Cape Verdean, and Guinean communities. The city is home to as many as 20,000 French expatriates.[citation needed] France still maintains an air force base at Yoff and the French fleet is serviced in Dakar's port.

Beginning 1978 and until 2007, Dakar was frequently the ending point of the Dakar Rally.

Geography

editDakar is located on the Cap-Vert peninsula on the Atlantic coast and is the westernmost city on the African mainland.

Climate

editDakar has an ocean-influenced hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSh), with a short rainy season and a lengthy dry season. Dakar's rainy season lasts from July to October, while the dry season covers the remaining eight months. The city sees approximately 411 mm (16.2 in) of rainfall per year.

Dakar between December and May is usually very warm with daily temperatures around 25–28 °C (77.0–82.4 °F). Nights during this time of the year are warm, some 18–20 °C (64.4–68.0 °F). However, between May and November the city becomes decidedly hotter with daily highs reaching 29–31 °C (84.2–87.8 °F) and night lows a little bit above 23–25 °C (73.4–77.0 °F). Notwithstanding this hotter season, Dakar's weather is far from being so hot as experienced in inland Sahelian cities like Niamey and N'Djamena, where temperatures hover above 36 °C (96.8 °F) for much of the year. Dakar is cooled year-round by sea breezes.

| Climate data for Dakar (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.5 (97.7) |

39.8 (103.6) |

40.4 (104.7) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

39.4 (102.9) |

33.5 (92.3) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

40.3 (104.5) |

39.4 (102.9) |

40.4 (104.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 25.9 (78.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25 (77) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

18 (64) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

21 (70) |

22.0 (71.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.8 (58.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.2 (0.05) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

7 (0.3) |

52.8 (2.08) |

165.6 (6.52) |

138.4 (5.45) |

26.3 (1.04) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.4 (0.02) |

392.5 (15.49) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 26.8 |

| Source: NOAA NCEI[17] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Dakar International Airport, Senegal (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.5 (97.7) |

39.8 (103.6) |

40.4 (104.7) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

39.4 (102.9) |

33.5 (92.3) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

40.3 (104.5) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.4 (104.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.1 (79.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.5 (88.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 2.0 (0.08) |

1.0 (0.04) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

10.0 (0.39) |

61.0 (2.40) |

165.0 (6.50) |

134.0 (5.28) |

37.0 (1.46) |

1.0 (0.04) |

1.0 (0.04) |

411 (16.2) |

| Average rainy days | 1.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 7.0 | 12.8 | 9.4 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 41.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 75 | 76 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 77 | 79 | 81 | 79 | 74 | 66 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 244.9 | 245.8 | 285.2 | 288.0 | 291.4 | 252.0 | 232.5 | 223.2 | 219.0 | 257.3 | 249.0 | 238.7 | 3,031.6 |

| Source: DWD[18] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 °C (72 °F) | 20 °C (68 °F) | 20 °C (68 °F) | 21 °C (70 °F) | 23 °C (73 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) |

Climate change

editA 2019 paper published in PLOS One estimated that under Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5, a "moderate" scenario of climate change where global warming reaches ~2.5–3 °C (4.5–5.4 °F) by 2100, the climate of Dakar in the year 2050 would most closely resemble the current climate of Praia in Cape Verde. The annual temperature would increase by 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), and the temperature of the warmest and the coldest month by 1.4 °C (2.5 °F) and 1.6 °C (2.9 °F), respectively.[20][21] According to Climate Action Tracker, the current warming trajectory appears consistent with 2.7 °C (4.9 °F), which closely matches RCP 4.5.[22]

Moreover, according to the 2022 IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Dakar is one of 12 major African cities (Abidjan, Alexandria, Algiers, Cape Town, Casablanca, Dakar, Dar es Salaam, Durban, Lagos, Lomé, Luanda and Maputo) which would be the most severely affected by future sea level rise. It estimates that they would collectively sustain cumulative damages of US$65 billion under RCP 4.5 and US$86.5 billion for the high-emission scenario RCP 8.5 by the year 2050. Additionally, RCP 8.5 combined with the hypothetical impact from marine ice sheet instability at high levels of warming would involve up to US$137.5 billion in damages, while the additional accounting for the "low-probability, high-damage events" may increase aggregate risks to US$187 billion for the "moderate" RCP4.5, US$206 billion for RCP8.5 and US$397 billion under the high-end ice sheet instability scenario.[23] Since sea level rise would continue for about 10,000 years under every scenario of climate change, future costs of sea level rise would only increase, especially without adaptation measures.[24]

Administration

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

The city of Dakar is a commune (also sometimes known as commune de ville), one of the 125 communes of Senegal. The commune of Dakar was created by the French colonial administration on 17 June 1887, by detaching it from the commune of Gorée. The commune of Gorée, created in 1872, was itself one of the oldest Western-style municipalities in Africa (along with the municipalities of Algeria and South Africa).

The commune of Dakar has been in continuous existence since 1887, being preserved by the new state of Senegal after independence in 1960, although its limits have varied considerably over time. The limits of the commune of Dakar have been unchanged since 1983. The commune of Dakar is ruled by a democratically elected municipal council (conseil municipal) serving five years, and a mayor elected by the municipal council. There have been 20 mayors in Dakar since 1887. The first black mayor was Blaise Diagne, mayor of Dakar from 1924 to 1934. The longest-serving mayor was Mamadou Diop, mayor for 18 years between 1984 and 2002.

The commune of Dakar is also a department, one of the 45 departments of Senegal. This situation is quite similar to Paris, which is both a commune and a department. However, contrary to French departments, departments in Senegal have no political power (no departmental assembly), and are merely local administrative structures of the central state, in charge of carrying out some administrative services as well as controlling the activities of the communes within the department.

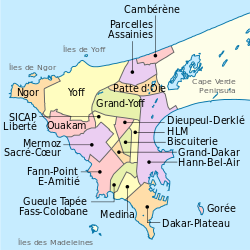

The department of Dakar is divided into four arrondissements: Almadies, Grand Dakar, Parcelles Assainies (which literally means "drained lots"; this is the most populous arrondissement of Dakar), and Plateau/Gorée (downtown Dakar).[25] These arrondissements are quite different from the arrondissements of Paris, being merely local administrative structures of the central state, like the Senegalese departments, and are thus more comparable to French departmental arrondissements.

In 1996, a massive reform of the administrative and political divisions of Senegal was voted by the Parliament of Senegal. The commune of Dakar, whose population approached 1 million inhabitants, was deemed too large and too populated to be properly managed by a central municipality, and thus on August 30, 1996, Dakar was divided into 19 communes d'arrondissement. These communes d'arrondissement were given extensive powers and are very much like regular communes. They have more powers than the arrondissements of Paris and are more akin to the London boroughs. The commune of Dakar was maintained above these 19 communes d'arrondissement, and it coordinates the activities of the communes d'arrondissement, much as Greater London coordinates the activities of the London boroughs. The 19 communes d'arrondissement belong to either of the four arrondissements of Dakar, and the sous-préfet of each arrondissement is in charge of controlling the activities of the communes d'arrondissement in his arrondissement.

The commune d'arrondissement of Dakar-Plateau (34,626 inhabitants), in the arrondissement of Plateau/Gorée, is the historical heart of the city, and most ministries and public administrations are located there. The densest and most populous commune d'arrondissement is Médina (136,697 inhabitants), in the arrondissement of Plateau/Gorée. The commune d'arrondissement of Yoff (55,995 inhabitants), in the arrondissement of Almadies, is the largest one, while the smallest one is the commune d'arrondissement of Île de Gorée (1,034 inhabitants), in the arrondissement of Plateau/Gorée.

Dakar is one of the 14 régions of Senegal. The Dakar région encompasses the city of Dakar and all its suburbs along the Cape Verde Peninsula. Its territory is thus roughly the same as the territory of the metropolitan area of Dakar. Since the administrative reforms of 1996, the régions of Senegal, which until then were merely local administrative structures of the central state, have been turned into full-fledged political units, with democratically elected regional councils, and regional presidents. They were given extensive powers, and manage economic development, transportation, or environmental protection issues at the regional level, thus coordinating the actions of the communes below them.

Notable sites

editThe city of Dakar is a member of the Organization of World Heritage Cities and contains several landmarks. One of the most notable is Deux Mamelles, twin hills located in Ouakam commune. The hills are the only high ground in the city, providing views of the entire area and sweeping views of the city. The first hill is topped with Mamelles Lighthouse built in 1864. The second hill has the newly completed African Renaissance Monument built on top, which is considered the tallest statue in Africa.[26]

Other landmarks of the city include the medina quarter located in Médina commune. Médina is originally built as a township for local populace during the French colonial-era. Today it is a traditional commercial center packed with tailors' shops. The most notable street market is Soumbédioune, which is also a major tourist attraction. The quarter also houses Dakar Grand Mosque at the heart of the commune, which is built in 1964 and one of the prominent landmarks of the city.[27][28]

Dakar is flanked by four small islands, île de Yoff, Île de N'Gor, Îles de la Madeleine and Île de Gorée. Île de N'Gor is on the northern shore of N'Gor commune, with beaches providing attractions such as surfing. N'Gor commune also has other popular beach resorts such as Plage de N'Gor.[29] Île de Gorée, formerly a slave island, is today a UNESCO World Heritage Site which preserves the colonial era architectures and facilities. Some notable places on the island include the Gorée Memorial which is a memorial for the slaves, and the House of Slaves which is a museum dedicated to the Atlantic slave trade. Today, the island is also hosting the art scene of the hundreds of local artists who line up their works at the outdoor exhibitions.[30][31]

Some other notable places include Layen Mausoleum which entombs the founder of the Layene Sufi tariqa, Palais Présidentiel which is the seat of the government constructed in 1907,[32] Place de l'Indépendance which is the central square of Dakar, Dakar Cathedral, and Cheikh Anta Diop University also known as the University of Dakar, which was established in 1957.

Places of worship

editThe most common places of worship in Dakar are Muslim mosques.[33] There are also Christian churches: Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Dakar (Catholic Church), Assemblies of God, Universal Church of the Kingdom of God.

Dakar was selected as the Capital of Islamic Culture for African Region for the year 2007 by the Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (ISESCO), honoring its Islamic heritage.[34] ISESCO and its parent organization Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) have held several regional and international conferences in the city,[35] best known for adoption of Dakar Declaration in 1991 which aimed at fostering the cooperation between the member states.[36] Dakar is also known as the birthplace of the Layene Brotherhood, a Sufi tariqa founded by Seydina Mouhammadou Limamou Laye in 1883 at the commune of Yoff. Seydina is buried in the Layen Mausoleum which is among the major landmarks of Dakar.[37] Today, Layene Brotherhood is consisted mostly of the Lebou people and based in the Cap-Vert area. It is also the third-biggest Sufi order in Senegal.

Prominent worshiping sites for Muslims in Dakar include the Grand Mosque of Dakar, built in 1964, which is situated at Allée Pape Gueye Fall of Medina, the Mosque of Divinity, constructed in 1973, situated in Ouakam, with the characteristic triangular windows, and Omarienne Mosque with minarets topped by green orbs.[31][38]

Culture

editIn Senegal, the traditional culture is very centred around the idea of family. This even includes the way that they eat. When it is time to eat a typical meal, someone will say "kay lekk" which means 'come eat'. Everyone will come together and sit around the plate and eat with their hands.[39] Some famous dishes include Cebbu Jën (Tiéboudienne) and Yassa. The etiquette of people in Dakar is very simple but very vital. To not greet someone upon sight is to portray rudeness and oftentimes ignorance. Due to French colonialism, the children of Dakar have a unique school system. The school will get a break at about midday and return home to get some rest. Since the population is majority Muslim, there are numerous daily Islamic activities ongoing, such as participating in noon prayer at the nearest mosque and attending the local mosque on Fridays. Music has a big influence on the youth with famous artists like Daara J Family who use their voice to represent the problems in their communities.[40]

Dakar is home to multiple national and international festivals, like World Festival of Black Arts, Festival international du film de quartier de Dakar, Dakar Biennale. It was also the location of Taf Taf, an international artist residency program.[41]

Museums

edit- IFAN Museum of African Arts or Musee Theodore Monod

- Henriette-Bathily Women's Museum

- House of Slaves

- Village des Arts

- Parc Forestier et Zoologique de Hann, aka the Senegal Zoo

- Museum of Black Civilisations[42]

- Dynamic Museum

Sports

editSports club AS Douanes are based in Sicap-Liberté; they play in the Senegal Premier League and previously won the 2014–15 Ligue 1 (Senegal) season.

Dakar used to be the finishing point of the Dakar Rally until 2007, before the event was moved to South America for the security concerns in Mauritania.[43]

Dakar was set to host the 2022 edition of the Youth Summer Olympics, however, the games have been postponed to 2026, it will be the first Olympic event to ever be held in Africa.[44]

Transport

editThe town is home to the Autonomous Port of Dakar and the terminus of the non-functioning Dakar-Niger railroad line.

Three trans-African automobile routes start from Dakar:

The Train Express Regional Dakar-AIBD (TER) will connect Dakar with Blaise Diagne International Airport (AIBD). An initial 36 km will link Dakar to Diamniadio and a second phase of 19 km would connect Dakar to the Blaise Diagne airport. A total of 14 train stations will be served and the fastest end-to-end journey will take 45 minutes. The railway is expected to carry 115 000 passengers per day. The TER's first test run launched on 14 January 2019 and the first passenger train ran in December 2021.[45][46][47]

Blaise Diagne International Airport is the city's international airport; it handles flights by several airlines, including Air France, Delta, Emirates and Emirates Sky Cargo, Iberia, TAP Air Portugal and Turkish, and is the hub of Senegal's flag carrier, Air Senegal.

Notable people

edit- Abdoulaye Faye, footballer

- Akon, R&B singer

- Baaba Maal, singer and guitarist

- Babacar Khane, yoga practitioner

- Boris Diaw, basketball player

- Bouna Coundoul, footballer

- Cheikh Anta Diop, Historian, anthropologist, physicist, politician Cheikh Anta Diop University

- Cheikh Samb, basketball player

- DeSagana Diop, former basketball player, head coach of the Westchester Knicks

- Didier Raoult, microbiologist and virologist, was born in Dakar in 1952

- Fatou Samba, member of South Korean girl group Blackswan

- Hamady N'Diaye, basketball player

- Ibou Badji, basketball player

- Ibrahim Ba, former footballer

- Ismaël Lô, singer-songwriter

- Idrissa Gueye, footballer

- Issa, R&B singer

- Macoumba Kandji, footballer

- Mamadou N'Diaye, former basketball player for Auburn University and the Toronto Raptors

- Mame Biram Diouf, footballer

- Marc Lièvremont, former rugby player and former head coach of the France national rugby union team

- Marcel Lefebvre, Founder of the SSPX, Apostolic delegate to Pope Pius XII, and Archbishop of Dakar.

- Mbaye Diagne, United Nations military observer and hero during the Rwandan genocide

- Mouhamed Gueye, basketball player

- Ofeibea Quist-Arcton, foreign correspondent for NPR News

- Orchestra Baobab

- Ousmane Barro, basketball player

- Papa Amadou Kante, basketball player

- Papa Bouba Diop, former footballer

- Pape Paté Diouf, football player

- Papiss Cisse, footballer

- Patrice Evra, former footballer,

- Patrick Vieira, former footballer

- Pélagie Gbaguidi, contemporary artist

- Sadio Mane, footballer

- N'Goné Fall, cultural consultant

- Sheck Wes, rapper, songwriter, model

- Ségolène Royal, French politician born in Dakar

- Souleyman Sané, former footballer

- Tacko Fall, basketball player

- Thione Seck, singer and songwriter

- Wasis Diop, musician

- Youssou N'Dour, singer and percussionist

International relations

editReferences

edit- ^ Senegal: Administrative Division

- ^ "climatemps.com".

- ^ Senegal: Administrative Division

- ^ "Dakar". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 17 December 2022. ("Definition of Dakar from the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus © Cambridge University Press")

- ^ "Dakar – definition of Dakar". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 29 October 2013. /dəˈkɑːr, dɑːˈkɑːr, ˈdækər/ "Define Dakar". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Roger J., Banton O., Barusseau J.-P., Castaigne P., Comte J.-C., Duvail C., Nehlig P., Noël B. J., Serrano O., Travi Y., Notice explicative de la cartographie multi-couches à 1/50 000 et 1/20 000 de la zone d’activité du Cap-Vert, Ministère des Mines, de l’Industrie et des PME, Direction des Mines et de la Géologie, Dakar, 245 p., 2009d.

- ^ Dinis Dias doubled Cap-Vert in 1444, but it is unclear if he sailed into the bay itself. Álvaro Fernandes anchored at the uninhabited island of Goree and lured and captured two natives off a Lebou fishing canoe before being driven off. The large slaving fleet of Lançarote de Freitas anchored in the bay, but their attempts to reach the mainland shore were fended off by missile fire and took no captives. The subsequent fleets of Estêvão Afonso (1446) and Valarte (1447) stopped briefly at Goree, but were also fended off the shores and took no captives. In the aftermath, Prince Henry the Navigator suspended all Portuguese expeditions beyond Cap-Vert for nearly a decade. There are no more recorded attempts until contact was made in 1456. (As reported in the 1453 chronicle of Gomes Eanes de Zurara)

- ^ B.W. Diffie and G.D. Winius (1977) Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415–1580 Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp.83-85

- ^ A. Teixeira da Mota (1946) "A descoberta da Guiné", Boletim cultural da Guiné Portuguesa, Vol. 1. No. 2 (Apr), p. 273-326.

- ^ a b A. Teixeira da Mota (1968) "Ilha de Santiago e Angra de Bezeguiche, escalas da carreira da India", Do tempo e da historia, Lisbon, v.3, pp.141-49.

- ^ Vespucci's letter from Bezeguiche is reproduced in F.A. de Varnhagen (1865) Amerigo Vespucci, pp.78-82.

- ^ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, US, 2013, p. 93

- ^ Winston Churchill, The Second World War, Vol 2 Book II Chapter xxiv 'Dakar'.

- ^ John Williams, The Guns of Dakar: September, 1940 (Heinemann Educational Books, 1976).

- ^ Martin Thomas, "The Anglo‐French divorce over West Africa and the limitations of strategic planning, June‐December 1940." Diplomacy and Statecraft 6.1 (1995): 252-278.

- ^ "Discours de réception de M. Jean-Claude JUNCKER comme membre associé étranger à l'Académie des Sciences morales et politiques" (PDF) (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-24.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020: Senegal-Dakar" (CSV). NOAA. Retrieved 2024-01-07.

- ^ "Climate Averages for Dakar International Airport" (PDF) (in German). DWD. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ "Climate Averages for Dakar International Airport, Senegal" (PDF). DWD. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ Bastin, Jean-Francois; Clark, Emily; Elliott, Thomas; Hart, Simon; van den Hoogen, Johan; Hordijk, Iris; Ma, Haozhi; Majumder, Sabiha; Manoli, Gabriele; Maschler, Julia; Mo, Lidong; Routh, Devin; Yu, Kailiang; Zohner, Constantin M.; Thomas W., Crowther (10 July 2019). "Understanding climate change from a global analysis of city analogues". PLOS ONE. 14 (7). S2 Table. Summary statistics of the global analysis of city analogues. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1417592B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217592. PMC 6619606. PMID 31291249.

- ^ "Cities of the future: visualizing climate change to inspire action". Current vs. future cities. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "The CAT Thermometer". Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Trisos, C.H., I.O. Adelekan, E. Totin, A. Ayanlade, J. Efitre, A. Gemeda, K. Kalaba, C. Lennard, C. Masao, Y. Mgaya, G. Ngaruiya, D. Olago, N.P. Simpson, and S. Zakieldeen 2022: Chapter 9: Africa. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 2043–2121

- ^ Technical Summary. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). IPCC. August 2021. p. TS14. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie, Government of Senegal (2005). Situation économique et sociale du Sénégal Edition 2005 (PDF) (Report) (in French). p. 163. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- ^ Les Mamelles – Dakar's Breasts. Lonely Planets. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ "Médina | Senegal | Sights". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ "Grande Mosquée | Senegal | Sights". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ Planet, Lonely. "Attractions in Senegal". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ^ "Trourist – Powered by Travelers. For Travelers". Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ a b "The culture capital of West Africa". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ "Palais Présidentiel | Senegal | Sights". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, ABC-CLIO, US, 2010, p. 2573-2575

- ^ Dakar: Capital of Islamic Culture for African Region for the year 2007. ISESCO. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ ISESCO and OIC to hold regional workshop in Dakar to examine implementation mechanisms of OIC Media Strategy in Countering Islamophobia and publicize Islam's middle stance among African countries Archived 2018-06-28 at the Wayback Machine. ISESCO. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ "Dakar Declaration" (PDF). IFRC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-03-26. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "Layen Mausoleum | Senegal | Sights". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ "Religious Beliefs In Senegal". WorldAtlas. 2017-04-25. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ "Senegal – Language, Culture, Customs and Etiquette". www.commisceo-global.com. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ^ "Hip-hop in Senegal". 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ^ "Taf taf – yhteisötaiteen residenssi Senegalissa". Turun taiteilijaseura. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Senegal unveils Museum of Black Civilisations", BBC News, December 6, 2018, retrieved August 10, 2019

- ^ "Motorcycle competitors race away as Dakar Rally leaves Buenos Aires". Clutch & Chrome. 2009-01-03. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ^ "Senegal officially awarded 2022 Summer Youth Olympic Games at IOC Session". www.insidethegames.biz. Oct 8, 2018. Retrieved Jul 26, 2020.

- ^ "Alstom train makes first run in Dakar". Railway Gazette International. Retrieved Jul 26, 2020.

- ^ "President Sall takes delivery of TER, Dakar's new train service - Journal du Cameroun". Archived from the original on 2019-01-16. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Ba, Diadie (December 27, 2021). "Senegal's new commuter train makes first journey from capital Dakar". www.reuters.com. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ L. Bigon (2009) A History of Urban Planning in Two West African Colonial Capitals: Residential Segregation in British Lagos and French Dakar, 1850–1930 Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

- ^ "Twin-cities of Azerbaijan". Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ "Monument in Dakar, on which "City Baku" was written in Russian and "City Dakar" in French". 2014.

- ^ "Città Gemellate" (in Italian). Comune di Milano. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "Town Twinning Agreements". Municipalidad de Rosario – Buenos Aires 711. Archived from the original on 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2014-10-14.

- ^ "DC Sister City Agreement" (PDF). The District of Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

Bibliography

editExternal links

edit- Dakar official website (in French) (archived)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.