Birdoswald Roman Fort[1] was known as Banna ("peak, horn" in Celtic) in Roman times,[2] reflecting the geography of the site on a triangular spur of land bounded by cliffs to the south and east commanding a broad meander of the River Irthing in Cumbria below.

| Banna | |

|---|---|

| |

Location in Cumbria | |

| Known also as | Birdoswald Roman Fort |

| Founded | c. 112 AD |

| Abandoned | c. 500 AD |

| Place in the Roman world | |

| Province | Britannia |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 54°59′22″N 2°36′08″W / 54.9894°N 2.6023°W |

| County | Cumbria |

| Country | England |

| Website | Birdoswald Roman Fort |

It lies towards the western end of Hadrian's Wall and is one of the best preserved of the 16 forts along the wall. It is also attached to the longest surviving stretch of Hadrian's Wall.[3]

Cumbria County Council were responsible for the management of Birdoswald fort from 1984 until the end of 2004, when English Heritage assumed responsibility.

History

editThis western part of Hadrian's Wall was originally built using turf starting from 122 AD.[4] The stone fort was built some time after the wall, in the usual playing card shape, with gates to the east, west and south. It was 7.5 miles east from Camboglanna (Castlesteads) fort and 6.5 miles from Aesica (Great Chesters).

The fort was occupied by Cohors I Aelia Dacorum and by other Roman auxiliaries from approximately AD 126[5] to AD 400.

The two-mile sector of Hadrian's Wall either side of Birdoswald is also of major interest. It is currently the only known sector of Hadrian's Wall in which the original turf wall was replaced, probably in the 130s, by a stone wall approximately 50 metres further north, to line up with the fort's north wall, instead of at its east and west gates. The reasons for this change are unclear, although it has been plausibly suggested[6] that it was the result of changing signalling requirements, whilst Stewart Ainsworth of Time Team suggested it was a response to a cliff collapse into the river.[citation needed] At any rate, this remains the only area in which both walls can be directly compared.

As of 2005, it is the only site[citation needed] on Hadrian's Wall at which significant occupation in the post-Roman period has been proven. Excavations between 1987 and 1992 showed an unbroken sequence of occupation on the site of the fort granaries, running from the late Roman period until possibly 500AD.[citation needed] The granaries were replaced by two successive large timber halls, reminiscent of others found in many parts of Britain dating to the fifth and sixth centuries. Tony Wilmott (co-director of the excavations) has suggested that,[citation needed] after the end of Roman rule in Britain, the fort served as the power-base for a local warband descended from the late Roman garrison, possibly deriving legitimacy from their ancestors for several generations.

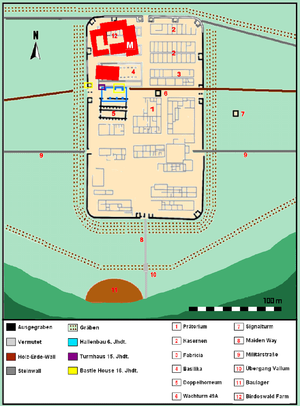

Layout

editInside were built the usual stone buildings, a central headquarters building (principia), granaries (horrea), and barracks. Unusually for an auxiliary fort, it also included an exercise building (basilica exercitatoria), perhaps reflecting the difficulties of training soldiers in the exposed site in the north of England.

Geophysical surveys detected vici (civilian settlements) of different characters on the eastern, western and northern sides of the fort.[7] A bathhouse was also located in the valley of the River Irthing.[8]

Other remains

editApproximately 600 metres east of Birdoswald, at the foot of an escarpment, lie the remains of Willowford bridge which carried Hadrian's Wall across the River Irthing. The westward movement of the river course over the centuries has left the east abutment of the bridge high and dry, while the west abutment has probably been destroyed by erosion. Nevertheless, the much-modified visible remains are highly impressive. Until 1996, these remains were not directly accessible from the fort, but they can now be reached by a metal footbridge over the Irthing.

The Vicus (civil settlement) was immediately south-west of the fort and a cemetery was south-east of the fort near the edge of the Irthing escarpment.

The fort at Birdoswald was linked by a Roman road to the outpost fort of Bewcastle, seven miles to the north. Signals could be relayed between the two forts by means of two signalling towers.[citation needed]

History of excavations

editThe fort has been extensively excavated for over a century, with twentieth century excavations starting in 1911 by F.G. Simpson and continuing with Ian Richmond from 1927 to 1933 .[9] The gateways and walls were then re-excavated under the supervision of Brenda Swinbank and J P Gillam from 1949 to 1950.[10]

Extensive geophysical surveys, both magnetometry and earth resistance survey, were conducted by TimeScape Surveys (Alan Biggins & David Taylor, 1999 & 2004) between 1997 -2001. These surveys established that the sub-surface remains in the fort were well preserved.

An area between the fort and the escarpment was excavated by Channel 4's archaeological television programme Time Team in January 2000. The excavation detected signs of an extramural settlement (vicus), but the area is liable to erosion and the majority of the vicus could have fallen over the cliffs.

In 2021 Newcastle University, Historic England, and English Heritage launched a major new archaeological excavation at the site.[11]

Birdoswald Roman Fort today

editToday the fort's site is operated by English Heritage as Birdoswald Roman Fort. The visitor centre features displays and reconstructions of the fort, exhibits about life in Roman Britain, the site's history through the ages, and archaeological discoveries in the 19th and 20th centuries. Visitors can walk outside along the excavated remains of the fort.

References

edit- ^ "Research History". Birdoswald Project. 3 June 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Rivet, A. L. F.; Smith, Colin (1979). The Place-Names of Roman Britain. London: B. T. Batsford. pp. 261–262. ISBN 0713420774. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ "Birdoswald Roman Trail Hadrian's Wall". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Hogan, C.Michael (2007) Hadrian's Wall, ed. A. Burnham, The Megalithic Portal

- ^ Spaul, John COHORS 2 (2000)

- ^ Woolliscroft D.J., "Hadrian's Wall from the air", Tempus, ISBN 0-7524-1946-3

- ^ "BBC Two - Digging for Britain, Series 9, Episode 6". BBC. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Last chance to see Birdoswald Hadrian's Wall Roman bathhouse". BBC News. 16 June 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Research on Birdoswald Roman Fort | English Heritage". English Heritage. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Gillam, J. P. (1950). "Recent excavations at Birdoswald" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society: 63, 64. doi:10.5284/1062766.

- ^ "Partnership aims to transform research on Hadrian's Wall". Press Office. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- Biggins, J. A. and Taylor, D. J. A., 1999, A Survey of the Roman Fort and Settlement at Birdoswald, Cumbria. Britannia. 30. 91–110.

- Biggins, J. A, and Taylor, D. J. A., 2004, Geophysical Survey of the Vicus at Birdoswald Roman Fort, Cumbria, Britannia 35, 159–178.

- Gillam, J. P. (1950). "Recent excavations at Birdoswald" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society: 63, 64. doi:10.5284/1062766.

- Hogan, C.Michael (2007) Hadrian's Wall, ed. A. Burnham, The Megalithic Portal

- Wilmott, Tony (2001), Birdoswald Roman Fort, Tempus, ISBN 978-0-7524-1913-8

- Wilmott, Tony; English Heritage (2005), Birdoswald Roman fort, English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-956-1

- Woolliscroft D.J.(2001), "Hadrian's Wall from the air", Tempus,ISBN 0-7524-1946-3

External links

edit- Visitor information : English Heritage

- Time Team 2000 excavation

- Interactive tour

- Visit Cumbria information on Birdoswald, including aerial photograph

- Review of English Heritage booklet

- iRomans Website showing Birdoswald objects at Tullie House Museum and the forts position on the wall

- Birdoswald at www.Roman-Britain.co.uk