Aesica (modern name Great Chesters) was a Roman fort, one and a half miles north of the small town of Haltwhistle in Northumberland, (not be confused with Chesters fort [Cilurnum]). It was the ninth fort on Hadrian's Wall, between Vercovicium (Housesteads) 6.0 miles to the east and Banna (Birdoswald) 6.5 miles to the west.

| Aesica | |

|---|---|

| Northumberland, England, UK | |

Remains of Aesica Roman Fort (West Gate) | |

Location in Northumberland | |

| Coordinates | 54°59′42″N 2°27′50″W / 54.995°N 2.464°W |

| Grid reference | NY703667 |

Its main purpose was to guard the Caw Gap where the Haltwhistle Burn crosses the Wall.[1]

Name

editDuring the Roman period the fort was known as Æsica[2] or Esica.[3][4]

The name Æsica may be derived from the Celtic god Æsus.[c] If so then the name might be interpreted as:

- " being of the kind of " Æsus

- " association with " Æsus

- " abounding in " Æsus

Æsus is known to have been associated with water and river systems; the name might have been related to a remarkable aqueduct system that drew water from the Haltwhistle Burn – Caw Burn directly into the fort.

Description

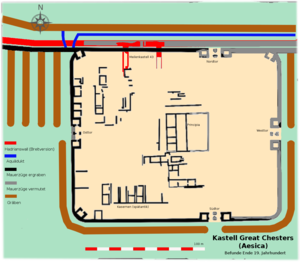

editIt is believed that the fort was completed in the year 128 AD, later than most of the wall forts as it was an afterthought to the original plan in which Milecastle 43 was built where the later north-west corner of the fort was constructed, and had to be demolished.[8] The fort was rectangular in plan with towers at each corner and measuring 355 feet (108 m) north to south by 419 feet (128 m) east to west, occupying a comparatively small area of 3 acres (12,000 m2). The fort had three main gates; south, east and west, with double portals with towers. At some time the west gate was completely blocked up.

Remarkably there are "broad wall" foundations of Hadrian's Wall a few metres north of the later proper "narrow gauge" wall which, unlike elsewhere, did not use the earlier foundations. This indicates the fort was started after the initial wall construction after which the later wall was used as the north wall of the fort.[9]

In addition, notably there are four ditches outside the western wall of the fort, but only a single ditch on the southern and eastern sides which indicates that the flat approach from the west was a defensive concern, while on the southern side the ditch alone interfered with the Vallum structure which clearly existed before the fort was built.[9]

The Roman Military Way entered by the east gate and left by the west gate. A branch road from the Roman Stanegate entered by the south gate which crossed the Vallum south of the fort.

A vicus lay to the south and east of the fort and several tombstones have been found there.

Roman aqueduct

editThe fort was supplied with water by a remarkable aqueduct system that drew water from the Haltwhistle Burn – Caw Burn directly into the fort. The aqueduct wound 6.0 miles (9.7 km) from the head of Caw Burn, north of the Wall, although the direct distance was only about 2.0 miles (3.2 km).[1][d] [f]

Garrison

editThe 2nd-century garrisons were the Sixth Cohort of Nervians, followed by the Sixth Cohort of Raetians. The 3rd-century garrison was the Second Cohort of Asturians with a detachment of Raeti Gaeseti.

Excavations

editExcavations were carried out in 1894, during which the ramparts were cleared. A barrack block was found and headquarters building (principia), together with its vaulted underground strong room. The west tower of the south gate was found to contain a hoard of jewellery, which included an enamelled brooch shaped as a hare, a gilded bronze brooch described as a masterpiece of Celtic art, a silver collar with a pendant, a gold ring and a bronze ring with a Gnostic gem.

In 1897 a bathhouse was discovered, 100 yards (91 m) to the south, east of the road to the Stanegate. It includes a dressing room, latrine, cold room with cold bath, dry-heat room, warm steam room and hot steam room.

References

edit- ^ a b *"Hadrian's Wall - Fort - Great Chesters (Aesica)". Roman-Britain. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ Notitia Dignitatum

- ^ Ravenna Cosmography

- ^ Rudge Cup inscription: MAIS ABALLAVA VXELODVNVM CAMBOG...S BANNA ESICA

- ^ James 2019, p. 223.

- ^ James 2019, p. 159.

- ^ James 2019, p. 132.

- ^ "Hadrian's Wall - Milecastle 43 - Great Chesters". Roman Britain. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Hadrian's Wall - Fort - Great Chesters (Aesica)". Roman Britain. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b Graham 1984, pp. 179.

Notes

edit- ^ Brittonic Language ( Alan James ) < -ǭg > . . .Adjectival and nominal suffix, indicating ‘being of the kind of’, ‘association with’, ‘abounding in’, the stem-word. It occurs very widely in river-names, hill-names and other topographic names, see CPNS 447-50. . . .[5]

- ^ Brittonic Language ( Alan James ) < -īg, -eg > . . .Early Celtic adjectival suffix *-ico-/ā- > -īg (masculine), -eg (feminine). The sense is similar to that of –ǭg,[a] . . .[6]

- ^ Brittonic Language ( Alan James ) < *Ẹ:s > . . .Early Celtic *ēs- or *ais- > Br *ẹ:s-; Latinised as Esus, Æsus, Hesus. . . .the fort-name Æsica or Esica PNRB p. 242, on Hadrian’s Wall at Great Chesters Ntb, is pretty certainly formed from the Latinised name + the Celtic adjectival suffix –icā- (see –īg) [b] . . .[7]

- ^ Hadrians Wall in the days of the Romans ( Frank Graham ) . . . Dr John Lingard (1771 – 1851) writing in 1807 was the first to notice the remarkable Roman aqueduct to be found here. He mentioned that the "water for the station was brought by a winding aqueduct still visible from the head of Haltwhistle Burn – Caw Burn. It winds down five miles".The aqueduct is actually six miles long but because it was necessary to wind to keep the water flow the direct line is just a little over two miles. Only one bridge was necessary and although it has gone its site is called Banks Bridge today.The aqueduct is marked on the OS map. . . .[10]

- ^ Hadrians Wall in the days of the Romans ( Frank Graham )

. . . Roman aqueduct's are recorded in inscriptions from:

- Chesters (Cilurnum)

- South Shields

- Chester-le-Street (Concangis)

- ^ Aesica is the only Roman fort on Hadrian's Wall known to have had such a system, although there is evidence to suggest that other forts might have used aqueduct's on a smaller scale. [e]

Sources

edit- Graham, Frank (1984). Hadrians Wall in the days of the Romans. FRANK GRAHAM. ISBN 0-85983-177-9.

- James, Alan G. (2019). "The Brittonic Language in the Old North, A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence, Volume 2" (PDF). Scottish Place-Name Society. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- J. Collingwood Bruce, Roman Wall (1863), Harold Hill & Son, ISBN 0-900463-32-5

- Frank Graham, The Roman Wall, Comprehensive History and Guide (1979), Frank Graham, ISBN 0-85983-140-X

External links

edit- AESICA at www.Roman-Britain.co.uk

- AESICA FORT Hadrian's Wall as it exists today