Amesbury is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States, located on the left bank of the Merrimack River near its mouth, upstream from Salisbury and across the river from Newburyport and West Newbury. The population was 17,366 at the 2020 United States Census.[3] A former farming and mill town, Amesbury is today largely residential. It is one of the two northernmost towns in Massachusetts (the other being neighboring Salisbury).

Amesbury, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

| City of Amesbury | |

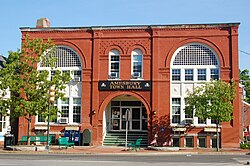

Amesbury City Hall | |

|

| |

| Nickname: Carriagetown | |

| Motto: "Make history here!"[1] | |

Location in Essex County and Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 42°51′30″N 70°55′50″W / 42.85833°N 70.93056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Essex |

| Settled | 1642 |

| Incorporated (town) | 1668 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1996 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council city |

| • Mayor | Kassandra Gove |

| Area | |

• Total | 13.73 sq mi (35.57 km2) |

| • Land | 12.29 sq mi (31.84 km2) |

| • Water | 1.44 sq mi (3.73 km2) |

| Elevation | 50 ft (15 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 17,366 |

| • Density | 1,412.79/sq mi (545.48/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 01913 |

| Area code | 351 / 978 |

| FIPS code | 25-01260, 25-01185 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0618292 |

| Website | City of Amesbury Official Web Site |

History

editPre-Colonial Period

editAt the time of European contact and colonization, the area north of the Merrimack River was inhabited by the Pentucket Tribe of the Pennacook confederation.[4] Several places in Amesbury retain or have been returned to indigenous names including the Powwow River and Hill, and Lake Attitash.[5][6]

Colonial Period

editPlantation at Merrimac

editIn 1637, the first English settler in the Salisbury-Amesbury region, John Bayly, crossed the Merrimack River from the new settlement at Newbury, built a log cabin, and began to clear the land for cultivation. He intended to send for his wife and children in England, but they never joined him.[7] He and his hired man, William Schooler, were arrested for a murder Schooler had committed.[7] Schooler was hanged for the murder but Bayly was acquitted.[7] Given the fishing rights on the river by the subsequent settlement, provided he would sell only to it, he abandoned agriculture for fishing.[8]

On September 6, 1638, the General Court of Massachusetts created a plantation on behalf of several petitioners from Newbury, on the left bank of the Merrimack, as far north as Hampton, to be called Merrimac.[9][10][11] They were given permission to associate together as a township.[11] The area remained in possession of the tribes along the Merrimack, who hunted and fished there.[11]

The settlers of the plantation, who entered Massachusetts Bay Colony, were rebels in a cause that was settled by the English Civil War (1642–1651).[12] Although nominally subjects of the crown, they did not obey it.[13] The settlers maintained close ties with the Parliamentary cause in Britain.[12] The supreme government of the colony was the General Court, which functioned autonomously, passing its own laws, establishing courts, incorporating townships and providing for the overall defense of the colony.[13] They established a Puritan church rather than the Church of England.[12]

In the early spring of 1639, approximately 60 planters took up residence on land cleared by the natives. In May, an elected planning committee laid out the green, the initial streets, the burial ground, and the first division into lots, apportioning the size of a lot to the wealth of the settler.[14] In November, the General Court appointed a government of six, which required that every lot owner take up residence on his lot.[15] They began to assign lots west of the Pow-wow river. The town was originally named Colchester, but was renamed Salisbury in October 1640, potentially at the suggestion of Christopher Batt, from Salisbury, England.[8] Batt trained the militia in the town.[8] The incorporation of the town granted it legal recognition by the colony to a township of that name, with its own government, empowered by citizens populating a territory of legally defined boundaries.[8] The original Salisbury was many times larger than the present. From it several townships were later separated.[16]

On January 12, 1641, a town meeting ordered the first roads north and west of the Pow-wow River to be built.[17] On April 21, another meeting granted William Osgood 50 acres of "upland" and 10 of "meadow" along the Pow-wow River, provided he build a sawmill for the town to use. It utilized a water wheel driven by the Pow-wow River.[17] The mill produced lumber for local use and pipe-staves for export.[17] A gristmill was added to the Pow-wow river location in 1642.[18] The Powwow River provided water power for a subsequent mill complex.[18] In 1642, the town wanted families to take up residence west of the Pow-wow and form a "New Town." No volunteers responded.[18]

In 1643, the General Court divided Massachusetts Bay Colony into four counties: Essex, Norfolk, Middlesex and Suffolk.[19] Norfolk contained Salisbury, Hampton, Haverhill, Exeter, Dover, and Strawberry Bank (Portsmouth).[19] This division was a legal convenience based on the distribution of courts.[19] Since the first establishment of four courts on March 3, 1635, the General Court had found it necessary to multiply and distribute courts, so that the magistrates would not spend time in travel that they needed for settling case loads. The main requirement for membership in a shire was incorporation.[20]

Separation from Salisbury

editPrivate occupation of the west bank of the Pow-wow River went on as East Salisbury citizens sold their property and moved to New Town.[21] However, New Town remained a paper construct without enforcement.[21] On January 14, 1654, articles of agreement adopted at town meeting divided Salisbury into Old Town and New Town, each to conduct its own affairs.[21] The border was the Pow-wow.[21] The agreement went into effect on January 19, 1655. In New Town, a new government was voted in, which claimed authority over "all matters of publicke concernment."[22] They still paid taxes to Old Town and expected services from it. The board of Old Town contained some members from New Town for fair representation.[23] This agreement also was known as a "settlement".

On May 26, 1658, New Town petitioned the General Court for independent town status, but the Old Town denied the petition.[24] The Old Town required all inhabitants, including those in the New Town, to attend church in Old Town and fined settlers for each missed meeting[24] The church and preacher were maintained from taxes.[24] Minister Joseph Peasley of New Town and his congregation attempting to defy the General Court were summoned into District Court at Ipswich "to answer for their disobedience", were fined there and Peasly was enjoined from preaching.[24] Another petition for separation was denied in 1660.[25]

The burden of attending church several miles away became so great that New Town built a new meeting house and requested the General Court to find a preacher.[26] The court yielded to the petition of 1666, granting the "liberty of a township" to New Town.[26] The town was unofficially incorporated, meaning a government was constituted and officers elected, on June 15.[26] It was named New Salisbury, but in 1667 the name was changed to Amesbury on the analogy of Amesbury, England, which was next to Salisbury, England.[27] Amesbury was officially granted incorporation under that name on April 29, 1668.[27]

After King Phillips War (1675–1678), an effort by the natives to rid themselves of the colonists, the Royal Province of New Hampshire was created and took away several towns in northern Norfolk shire.[20][28] Massachusetts was reduced in size from most of New England to roughly its current borders. The Court dissolved Norfolk Shire, transferring Salisbury and Amesbury to Essex County.[20]

Industrial Era

editBeginning as a modest farming community, Amesbury developed a maritime and industrial economy. Shipbuilding, shipping and fishing were also important.[29][30] The ferry across the Merrimack River to Newburyport was a business until the construction of bridges to cross the river.[31] Newton, New Hampshire, was set off from Amesbury in 1741, when the border between the two colonies was adjusted.[32][33]

In the 19th century, textile mills were built at the falls,[30] as was a nail-making factory.[34] Beginning around 1800, Amesbury began building carriages,[35] a trade which evolved into the manufacture of automobile bodies.[36] Prominent manufacturers included Walker Body Company, Briggs Carriage Company, and Biddle and Smart.[37][38] The industry ended with the Great Depression.[36] The Merrimac Hat Company was founded in 1856 and became one of the top hat producers in the nation.[39] Amesbury also produced Hoyt's Buffalo Brand Peanut Butter Kisses.[40]

In 1876, Merrimac was created out of West Amesbury.[41][42] In 1886, West Salisbury was annexed to Amesbury, unifying the mill areas on both banks of the Pow-wow River.[43]

Newspapers in the 19th century included the Amesbury Daily News, Merrimac Journal, Morning Courier, Evening Courier, New England Chronicle, Transcript, and the Villager.[44][45] Newspapers in the 20th century included the Amesbury Advocate, Amesbury News, Amesbury Times, and Leader.[45]

Twentieth century and beyond

editIn 1996, the town changed its status to a city, and adopted the mayor and municipal council form of government, although it retained the title "Town of Amesbury", as voters "thought Amesbury was too small and quaint to be a city".[46] Voters approved a charter amendment in November 2011 changing the city's official name to the "City of Amesbury" and removing references to the old "Town of Amesbury" name.[47] The name change took effect in March 2012.[48] The city's seal still bears the name "Town of Amesbury", although the City put forth a bill in 2013 to correct the seal with the new name.[46]

The community has several buildings that feature early architecture, particularly in the Federal and Victorian styles.[49] The "Doughboy", a memorial sculpture by Leonard Craske, stands on the front lawn of the Amesbury Middle School.[50] It was dedicated November 11, 1929.[50] Craske is best known as sculptor for the "Fishermens' Memorial" in Gloucester.[51] There is also a monument erected to Josiah Bartlett, the first signer of the Declaration of Independence, who was born in Amesbury.[52]

-

Thomas Macy House c. 1905

-

Mills in 1914

-

Whittier's home in 1909

Geography

editAmesbury is located at 42°51′29″N 70°55′50″W / 42.85806°N 70.93056°W.[53] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.7 square miles (35.5 km2), of which 12.3 square miles (31.8 km2) is land and 1.5 square miles (3.8 km2), or 10.65%, is water.[54] Amesbury is drained by the Powwow River. Powwow Hill, elevation 331 feet (101 m), is the highest point in town. Once the site of Indian gatherings, or "powwows", it has views to Maine and Cape Ann. Amesbury is the second northernmost town in Massachusetts, its northernmost point coming just south of the northernmost point of the state, in Salisbury. Amesbury lies along the northern banks of the Merrimack River and is bordered by Salisbury to the east, Newburyport to the southeast, West Newbury to the southwest, Merrimac to the west, and South Hampton, New Hampshire, to the north.

The Powwow River bisects the town, joined by the Back River near the town center. The river flows through Lake Gardner and Tuxbury Pond, which are two of several inland bodies of water in town, including Lake Attitash (which is partially in Merrimac), Meadowbrook Pond, and Pattens Pond. Several brooks also flow through the town. Amesbury has a town forest, which is connected to Woodsom Farm, as well as Powwow Conservation Area, Victoria Batchelder Park and Amesbury Golf & Country Club.

Transportation

editAmesbury is served by two interstate highways. Interstate 495 runs from west to east through town, ending at Interstate 95 just over the Salisbury town line. It has two exits in town, Exit 54 at Massachusetts Route 150 (which lies entirely within Amesbury, and leads to New Hampshire Route 150) and Exit 55 at Massachusetts Route 110, which also provides the town's only direct access to Interstate 95 at Exit 58. I-95 crosses the southeast corner of town, entering along the John Greenleaf Whittier Memorial Bridge, a steel through-truss bridge crossing the Merrimack River. The Whittier Memorial Bridge lies just west of the town's only other bridges across the Merrimack, the Derek S. Hines Memorial Bridge, which connects Amesbury to Deer Island (which is still part of Amesbury), and the Chain Bridge, the only suspension bridge in Massachusetts, which spans from Deer Island to Newburyport. The current version was built in 1909, but was predated by the 1810 suspension bridge, one of the oldest suspension bridges in the country. The Chain Bridge and its counterparts over the years have been the main entryways into town across the Merrimack, and until the building of the Newburyport Turnpike Bridge, it was the easternmost bridge on the Merrimack River.

MVRTA provides bus service in Amesbury. Route 51 connects to the Haverhill train station. Route 54 connects to Newburyport train station.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 2,471 | — |

| 1850 | 3,143 | +27.2% |

| 1860 | 3,877 | +23.4% |

| 1870 | 5,581 | +44.0% |

| 1880 | 3,355 | −39.9% |

| 1890 | 9,798 | +192.0% |

| 1900 | 9,473 | −3.3% |

| 1910 | 9,894 | +4.4% |

| 1920 | 10,036 | +1.4% |

| 1930 | 11,899 | +18.6% |

| 1940 | 10,862 | −8.7% |

| 1950 | 10,851 | −0.1% |

| 1960 | 10,787 | −0.6% |

| 1970 | 11,388 | +5.6% |

| 1980 | 13,971 | +22.7% |

| 1990 | 14,997 | +7.3% |

| 2000 | 16,450 | +9.7% |

| 2010 | 16,283 | −1.0% |

| 2020 | 17,366 | +6.7% |

| 2022* | 17,179 | −1.1% |

| * population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[66] | ||

Government

editAmesbury is part of the Massachusetts Senate's 1st Essex district.[67]

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third parties | Total Votes | Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 65.28% 6,786 | 32.00% 3,326 | 2.72% 283 | 10,395 | 33.29% |

| 2016 | 56.88% 5,174 | 35.52% 3,231 | 7.60% 691 | 9,096 | 21.36% |

| 2012 | 57.58% 4,863 | 40.58% 3,427 | 1.85% 156 | 8,446 | 17.00% |

| 2008 | 59.85% 5,111 | 37.73% 3,222 | 2.42% 207 | 8,540 | 22.12% |

| 2004 | 57.99% 4,589 | 40.79% 3,228 | 1.21% 96 | 7,913 | 17.20% |

| 2000 | 55.82% 3,866 | 36.15% 2,504 | 8.03% 556 | 6,926 | 19.67% |

| 1996 | 58.75% 3,774 | 27.62% 1,774 | 13.64% 876 | 6,424 | 31.13% |

| 1992 | 41.18% 2,857 | 28.51% 1,978 | 30.31% 2,103 | 6,938 | 10.87% |

| 1988 | 54.69% 3,352 | 43.50% 2,666 | 1.81% 111 | 6,129 | 11.19% |

| 1984 | 41.41% 2,395 | 58.04% 3,357 | 0.55% 32 | 5,784 | 16.63% |

| 1980 | 37.70% 2,076 | 43.24% 2,381 | 19.05% 1,049 | 5,506 | 5.54% |

| 1976 | 56.05% 3,001 | 40.89% 2,189 | 3.06% 164 | 5,354 | 15.17% |

| 1972 | 47.24% 2,432 | 52.25% 2,690 | 0.51% 26 | 5,148 | 5.01% |

| 1968 | 57.13% 2,820 | 38.78% 1,914 | 4.09% 202 | 4,936 | 18.35% |

| 1964 | 71.39% 3,520 | 28.21% 1,391 | 0.41% 20 | 4,931 | 43.18% |

| 1960 | 56.68% 3,198 | 43.12% 2,433 | 0.19% 11 | 5,642 | 13.56% |

| 1956 | 36.35% 1,978 | 63.47% 3,454 | 0.18% 10 | 5,442 | 27.12% |

| 1952 | 42.50% 2,430 | 57.28% 3,275 | 0.23% 13 | 5,718 | 14.78% |

| 1948 | 54.57% 2,789 | 44.06% 2,252 | 1.37% 70 | 5,111 | 10.51% |

| 1944 | 54.09% 2,689 | 45.64% 2,269 | 0.26% 13 | 4,971 | 8.45% |

| 1940 | 55.01% 2,934 | 44.24% 2,360 | 0.75% 40 | 5,334 | 10.76% |

Demographics

editAs of the census of 2000, there were 16,450 people, 6,380 households, and 4,229 families residing in the city.[69] The population density was 1,326.3 inhabitants per square mile (512.1/km2). There were 6,623 housing units at an average density of 206.2 persons/km2 (534.0 persons/sq mi). The racial makeup of the city was 97.2% White, 0.6% African American, 0.22% Native American, 0.9% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 6,380 households, out of which 34.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.2% were married couples living together, 11.3% have a woman whose husband does not live with her, and 33.7% were non-families. 26.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.52 and the average family size was 3.09.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 26.1% under the age of 18, 6.1% from 18 to 24, 33.8% from 25 to 44, 22.0% from 45 to 64, and 12.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $34,906, and the median income for a family was $62,875. Males had a median income of $25,489 versus $31,968 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,103. 5.9% of the population and 3.9% of families were below the poverty line.

Education

editThe major educational institutions are:

- Amesbury Public Schools

- SGT. Jordan Shay Memorial Lower Elementary School (K-2)

- Charles C. Cashman Elementary School (3–5)

- Amesbury Middle School (6–8)

- Amesbury High School (9–12)

- Amesbury Innovation High School (School of Choice)

- Sparhawk School (School of Choice)

In 2023, the Amesbury Elementary School closed following the construction of the Shay Memorial School, built on the same property as the Cashman Elementary School. Prior to this, both Amesbury Elementary School and Cashman Elementary School housed K-4 students, with students attending whichever school they lived closer to. Beginning in the 2024-2025 school year, all K-5 students were housed on the same property and divided by age between the Shay Memorial Lower Elementary School and the preexisting Cashman Elementary School.

Amesbury's high school football rival is Newburyport; the two teams play against each other every Thanksgiving Day. The Amesbury mascot is "Red Hawks," formerly the "Indians."[70][71]

Public library

editAs of 2012, the Amesbury Public Library pays for access to information resources produced by Brainfuse, Cengage Learning, EBSCO Industries, LearningExpress, Library Ideas, Mango Languages, NewsBank, Online Computer Library Center (OCLC), ProQuest, TumbleBook Library, World Book of Berkshire Hathaway, and World Trade Press.[72]

The Public Library houses an extensive Local History and genealogy collection which is open and available for research. [73]

Points of interest

edit- Alliance Park, site of the construction of the USS Alliance in 1777

- Amesbury Carriage Museum

- Amesbury Friends Meeting House (1850)

- Amesbury Hat Museum, which displays hats of the old Merrimack Hat Factory

- Amesbury Public Library

- Chain Bridge

- Bartlett Museum, Inc. (1870)

- Fortune Bar

- John Greenleaf Whittier House

- Lowell's Boat Shop (1793)

- Macy-Colby House (c. 1654)

- Mary Baker Eddy Historic House

- Old Powder House (1810)

- Rocky Hill Meeting House (c. 1785)

- Salisbury Point Railroad Historical Society

- Acorn Mountain Park

- Maples Crossing (2021)

Notable people

edit- Jimmy Bannon (1871–1948), outfielder in Major League Baseball[74]

- Josiah Bartlett (1729–1795), signer of the Declaration of Independence, fourth Governor of New Hampshire[75]

- Daniel Blaisdell (1762–1833), congressman from New Hampshire[76]

- Nathaniel Currier (1813–1888), American lithographer, Currier and Ives[77]

- Jeffrey Donovan (born 1968), actor; star of television show Burn Notice[78]

- Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910), founder of Christian Science[79]

- Robert Frost (1874–1963), poet[80]

- Susannah (North) Martin, victim of Salem witch trials in 1692[81]

- William A. Paine (1844–1929), businessman, co-founded the brokerage firm Paine Webber[82]

- Harriet Prescott Spofford (1835–1921), author[83]

- Paine Wingate (1739–1838), preacher, served in the Continental Congress; US senator and congressman[84]

- Al Capp, cartoonist, author of long running satirical strip Li'l Abner lived in Amesbury for most of his life and is buried in the town.

- John Greenleaf Whittier (1807–1892), poet[85]

International relations

editTwin towns – Sister cities

editAmesbury is twinned with:

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "City of Amesbury Brand Guidelines". amesburyma.gov. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ ""Census - Geography Profile: Amesbury Town city, Massachusetts"". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Perley, Sidney (1912). The Indian land titles of Essex County, Massachusetts. The Library of Congress. Salem, Mass. : Essex Book and Print Club. pp. Frontispiece map, pages 4-6.

- ^ Douglas-Lithgow, Robert Alexander (1909). Dictionary of American-Indian place and proper names in New England; with many interpretations, etc. Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. Salem, Mass., Salem Press. pp. Pages 100 and 148.

- ^ Perley, Sidney (1912). The Indian land titles of Essex County, Massachusetts. The Library of Congress. Salem, Mass. : Essex Book and Print Club. pp. Page 5.

- ^ a b c Merrill 1880, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d Merrill 1880, p. 22

- ^ Ryder, Jill (March 1, 2003). The Carriage Journal: Vol 40 No 2 March 2002. Carriage Assoc. of America. p. 57.

- ^ The New England Historical and Genealogical Register,: Volume 46 1892. Heritage Books. June 1997. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7884-0651-5.

- ^ a b c Merrill 1880, pp. 8.

- ^ a b c Massachusetts., Colonial Society of (1980). Seafaring in colonial Massachusetts : a conference held by the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, November 21 and 22, 1975. The Society. p. 17. OCLC 7321509.

- ^ a b Barnes, Viola Florence (1923). The Dominion of New England. Yale University Press. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Merrill 1880, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Merrill 1880, pp. 10–14

- ^ Arrington 1922, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Merrill 1880, pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b c Merrill 1880, pp. 22–25.

- ^ a b c Merrill 1880, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b c Arrington 1922, pp. 41–43.

- ^ a b c d Merrill 1880, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Merrill 1880, p. 54.

- ^ Merrill 1880, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d Merrill 1880, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Merrill 1880, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b c Merrill 1880, pp. 84–86

- ^ a b Merrill 1880, pp. 90–92.

- ^ "On July 24, 1679, New Hampshire became..." Chicago Tribune. July 24, 1986.

- ^ Brown, Nell Porter (June 16, 2015). "Dedicated to Craft". Harvard Magazine. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Exploring Historic Amesbury, Massachusetts". New England Today. February 12, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Callahan, Joe (August 11, 2016). "George Carr, pioneer in local ferry industry". The Daily News of Newburyport. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Suneson, Grant; Harrington, John. "From Alabama to Wyoming, this is how each state got its shape". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Merrill 1880, p. 164

- ^ Rockdale: The Growth of an American Village in the Early Industrial Revolution. U of Nebraska Press. January 1, 2005. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-8032-9853-8.

- ^ Merrill 1880, pp. 315–316

- ^ a b "Travel: Amesbury". Northshore Magazine. January 24, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Berry, Melissa (March 28, 2015). "Booming carriage industry brought Amesbury prominence". The Daily News of Newburyport. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Jim (June 30, 2018). "Antiques to highlight Amesbury car show". The Daily News of Newburyport. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "Hats off to a bygone era". Boston.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Lockwood, J. C. "Little city, big history: Author looks at Amesbury's industrial past". Wicked Local. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Leonard-Solis, Liam (July 24, 2015). "Merrimac asks to add Town Hall to national historic register". The Daily News of Newburyport. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Ryder, Jill (March 1, 2003). The Carriage Journal: Vol 40 No 2 March 2002. Carriage Assoc. of America. p. 59.

- ^ Court, Massachusetts General (1887). A Manual for the Use of the General Court. p. 112.

- ^ Rowell's American Newspaper Directory. NY: Printers' Ink Pub. Co. 1909. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ^ a b Boston Public Library, Microtext Department. "Massachusetts Newspapers" (PDF). Newspapers on Microfilm. Archived from the original on June 25, 2003. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ^ a b Cerullo, Mac (January 8, 2013). "Putting the seal on 'City of Amesbury'". Newburyport News.

- ^ Laidler, John (November 13, 2011). "Incumbent mayors all keep seats". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016.

- ^ "Town becomes a city on March 20". February 28, 2012. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023.

- ^ Editorial Staff (January 1, 2008). Massachusetts Historic Places Dictionary: Barnstable County-middlesex County/ Nantucket County-worcester County. State History Publications. ISBN 978-1-878592-67-5.

- ^ a b Rogers, Dave (May 19, 2014). "Amesbury gathers for rededication of Doughboy". The Daily News of Newburyport. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "Doughboy statue to be rededicated - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "A GREAT DAY FOR AMESBURY.; THE STATUE OF JOSIAH BARTLETT TO BE UNVEILED". The New York Times. July 4, 1888. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Amesbury Town city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020−2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Massachusetts General Court, "An Act Establishing Executive Councillor and Senatorial Districts", Session Laws: Acts (2011), retrieved April 15, 2020

- ^ "Election Results".

- ^ Census 2000 Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today

- ^ Kyle, Gaudet (December 6, 2022). "Amesbury picks 'Red Hawks' as new nickname". Newburyport Daily News. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "These Massachusetts schools still have Native American themed nicknames, mascots, or logos". February 16, 2017.

- ^ Amesbury Public Library. "Downloads & Databases". Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ^ Amesbury Public Library. "Local History". Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "James Henry Bannon". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Josiah Bartlett". Independence Hall Association. Archived from the original on February 13, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "BLAISDELL, Daniel, (1762 - 1833)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Currier & Ives - The History of the Firm". The Currier and Ives Foundation. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Jeffrey Donovan 'Burns' hot". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "AMESBURY, MASSACHUSETTS". Longyear Museum. Archived from the original on August 25, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Fagan, Deirdre J. (2007). Critical Companion to Robert Frost: A Literary Reference to His Life and Wor. Infobase Publishing. p. 412. ISBN 9781438108544.

- ^ "Susannah Martin: Accused Witch from Salisbury". History of Massachusetts. February 14, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Movers and Shakers: The 100 Most Influential Figures in Modern Business. Basic Books. 2003. p. 266. ISBN 9780738209142.

- ^ "Harriet Elizabeth Prescott Spofford Collection". Five College Archives & Manuscripts Collections. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "WINGATE, Paine, (1739 - 1838)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Tour the Home". Whittier Home Association. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Sister Cities | AMESBURY for AFRICA". amesburyforafrica.org. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

Publications

editBooks and articles

edit- Arrington, Benjamin F., ed. (1922). Municipal History of Essex County in Massachusetts. Vol. I (Tercentenary ed.). New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company.

- Merrill, Joseph (1880). History of Amesbury Including the First Seventeen Years of Salisbury to the Separation in 1654 and Merrimac from its Incorporation in 1876. Haverhill: Press of Franklin P. Stiles.

history of amesbury.

- Amesbury Vital Records to 1849.[permanent dead link] Published 1913. Transcribed and put online by John Slaughter and Jodi Salerno.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Merrill, Joseph, History of Amesbury, from the History of Essex County Volume 2 Chapter 125, pages 1495–1535, compiled by D. Hamilton Hurd, published by J.W. Lewis 1888.

Maps

edit- Sargeant, Christopher. 1794 Map of Amesbury.

- Clough, Aaron. 1795 Map of Salisbury.

- Nichols, W., J S Morse. 1830 Map of Amesbury.

- Anderson, Philander. 1830 Map of Salisbury.

- Beers, D.G. 1872 Atlas of Essex County, Massachusetts Amesbury. Plate 9. Amesbury and Salisbury Mills. Now Amesbury Center. Plate 12. Salisbury. Plate 15. West Amesbury now Merrimac. And East Salisbury. Plate 17. Salisbury Point. Plate 19. (Now The Point in Amesbury).

- Bigelow, E.H. Amesbury and Salisbury Mills. Bird's-eye view at the Boston Public Library website.

- Norris, George E. Amesbury. Panoramic View. Published 1890. Burleigh Lith. Est. At the Library of Congress website.

- Hughes & Bailey. Amesbury. Panoramic View. Published 1914.

- Walker, George H. 1884 Atlas of Essex County Massachusetts 1884 Map of Amesbury. Plate 169. Amesbury, Salisbury Point. Plate 74. Merrimac Center (was West Amesbury). Plate 151. Amesbury Village Mills. Plate 170-171. 1884 Map of Merrimac. Plate 172. 1884 Map of Salisbury. Plate 175. Salisbury Village Mills on the Powwow River. Plate. 176-177. East Salisbury. Plate 178. Danvers Catholic Church, Folger's Carriage Factory Amesbury. Plate 166.