Daniel Coit Gilman (/ˈɡɪlmən/; July 6, 1831 – October 13, 1908) was an American educator and academic.[1] Gilman was instrumental in founding the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College,[2] and subsequently served as the second president of the University of California, Berkeley, as the first president of Johns Hopkins University, and as founding president of the Carnegie Institution.

Daniel Coit Gilman | |

|---|---|

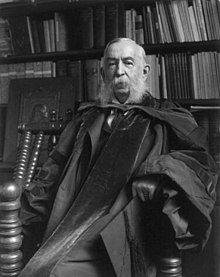

Gilman in c. 1890 | |

| President of Johns Hopkins University | |

| In office 1875–1901 | |

| Succeeded by | Ira Remsen |

| President of the University of California, Berkeley | |

| In office 1872–1875 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Durant |

| Succeeded by | W.T. Reid |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 6, 1831 Norwich, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | October 13, 1908 (aged 77) Norwich, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Van Winker Ketcham; Elizabeth Dwight Woolsey |

| Children | Alice; Elisabeth |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Profession | Academic administrator, educator, librarian, author |

| Institutions | Yale College University of California Johns Hopkins University Sheffield Scientific School Carnegie Institution |

| Signature | |

Eponymous halls at both Berkeley and Hopkins pay tribute to his service. He was also co-founder of the Russell Trust Association, which administers the business affairs of Yale's Skull and Bones society. Gilman served for twenty five years as president of Johns Hopkins; his inauguration in 1876 has been said to mark "the starting point of postgraduate education in the U.S."[3]

Biography

editEarly life and education

editHe was born in Norwich, Connecticut,[4] the son of Eliza (Coit) and mill owner William Charles Gilman, a descendant of Edward Gilman, one of the first settlers of Exeter, New Hampshire; of Thomas Dudley, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and one of the founders of Harvard College; and of Thomas Adgate, one of the founders of Norwich in 1659.[5] Daniel Coit Gilman graduated from Yale College in 1852 with a degree in geography.[6]

At Yale, he was a classmate of Andrew Dickson White, who would later serve as first president of Cornell University. The two were members of the Skull and Bones secret society, and traveled to Europe together after graduation and remained lifelong friends. Gilman was also a member of the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity. Gilman would later co-found the Russell Trust Association, the foundation behind Skull and Bones. After serving as attaché of the United States legation at St. Petersburg, Russia from 1853 to 1855, he returned to Yale and was active in planning and raising funds for the founding of Sheffield Scientific School. Gilman contemplated going into the ministry, and even obtained a license to preach, but later settled on a career in education.[7]

Career

editFrom 1856 to 1865, Gilman served as librarian of Yale College, and was also concerned with improving the New Haven public school system. When the Civil War broke out, Gilman became the recruiting sergeant for the Norton Cadets, a group of Yale graduates and faculty who drilled on the New Haven Green under the oversight of Yale professor William Augustus Norton.

In 1863, he was appointed professor of geography at the Sheffield Scientific School, and became secretary and librarian as well in 1866. Having been passed over for the presidency of Yale, for which post Gilman was said to have been the favorite of the younger faculty, he resigned these posts in 1872 to become the third president of the newly organized University of California, Berkeley.[7] His work there was hampered by the state legislature, and in 1875 Gilman accepted the offer to establish and become first president of Johns Hopkins University.

Before being formally installed as president in 1876, he spent a year studying university organization and selecting an outstanding staff of teachers and scholars. His formal inauguration, on 22 February 1876, has become Hopkins' Commemoration Day, the day on which many university presidents have chosen to be installed in office. Among the legendary educators he assembled to teach at Johns Hopkins were classicist Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, mathematician James Joseph Sylvester, historian Herbert Baxter Adams and chemist Ira Remsen.

In 1876, Gilman was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[8]

Gilman's primary interest was in fostering advanced instruction and research, and as president he developed the first American graduate university in the German tradition. The aim of the modern research university, said Gilman, was to "extend, even by minute accretions, the realm of knowledge"[9] At his inaugural address at Hopkins, Gilman asked: "What are we aiming at?" The answer, he said, was "the encouragement of research and the advancement of individual scholars, who by their excellence will advance the sciences they pursue, and the society where they dwell."[citation needed]

In 1884, Gilman was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.[10]

Gilman was also active in founding Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1889 and Johns Hopkins Medical School in 1893. He founded and was for many years president of the Charity Organization of Baltimore, and in 1897 he served on the commission to draft a new charter for Baltimore.[11] From 1896 to 1897, he was a member of the commission to settle the boundary line between Venezuela and British Guiana.[11]

Gilman served as a trustee of the John F. Slater[12] and Peabody education funds and as a member of John D. Rockefeller's General Education Board. In this capacity, he became active in the promotion of education in the southern United States. He was president of the National Civil Service Reform League (1901–1907) and the American Oriental Society (1893–1906), vice president of the Archaeological Institute of America, and executive officer of the Maryland Geological Survey.[13] He retired from Johns Hopkins in 1901, but accepted the presidency (1902–1904) of the newly founded Carnegie Institution of Washington.[14]

His books include biographies of James Monroe (1883) and James Dwight Dana, a collection of addresses entitled University Problems (1898), and The Launching of a University (1906).[citation needed]

Personal life

editGilman married twice. His first wife was Mary Van Winker Ketcham, daughter of Tredwell Ketcham of New York City. They married on December 4, 1861, and had two daughters: Alice, who married Everett Wheeler; and Elisabeth Gilman, who became a social activist and was a candidate for mayor of Baltimore, and for governor and senator of Maryland, on the Socialist Party of America ticket. Mary Ketcham Gilman died in 1869, and Daniel Coit Gilman married his second wife, Elizabeth Dwight Woolsey, daughter of John M. Woolsey of Cleveland, and niece of Yale president Theodore Dwight Woolsey, in 1877. Daniel Gilman's brother Edward Whiting Gilman was married to Julia Silliman, daughter of Yale University professor and chemist Benjamin Silliman. Daniel Coit Gilman died in Norwich, Connecticut.[7]

Legacy

editThe original academic building on the Homewood campus of the Johns Hopkins University, Gilman Hall, is named in his honor. In 1897, he helped found a preparatory school called 'The Country School for Boys' on the Johns Hopkins campus. Upon relocation in 1910, it was renamed in his honor and today, the Gilman School continues to be regarded among the nation's elite private boys' schools.[citation needed]

On the University of California, Berkeley campus, Gilman Hall, also named in his honor, is the oldest building of the College of Chemistry and a National Historic Chemical Landmark. Named for Gilman as well is Gilman Street in Berkeley. Gilman Drive, which passes through the University of California, San Diego campus in La Jolla, CA is also named for Gilman. The Daniel Coit Gilman Summer House, in Maine, was declared a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1965.[15] Gilman High School in Northeast Harbor, Maine, was named for Daniel Coit Gilman, who was active in local educational affairs, but it was later rebuilt and christened Mount Desert High School.

He was awarded American Library Association Honorary Membership in 1895.[16]

Published works by Daniel Coit Gilman

edit- Scientific Schools in Europe, Hartford, 1856

- A Historical Discourse Delivered in Norwich, Connecticut, September 7, 1859, at the Bi-Centennial Celebration of the Settlement of the Town, Boston, 1859

- The Library of Yale College: Historical Sketch, New Haven, 1860

- Our National Schools of Science, Cambridge, 1867

- Statement of the Progress and Condition of the University of California, Berkeley, 1875

- James Monroe in His Relations to the Public Service During Half a Century, 1776–1826, Boston, 1883

- The Benefits Which Society Derives from Universities, Baltimore, 1885

- An Address Before the Phi Beta Kappa Society of Harvard University, July 1, 1886, Baltimore, 1886

- Development of the Public Library in America, Ithaca, 1891

- Our Relations to Our Other Neighbors, Baltimore, 1891

- The Johns Hopkins University from 1873 to 1893, Baltimore, 1893

- Recollections of the Life of John Glenn Who Died in Baltimore, March 30, 1896, Baltimore, 1896[17][18]

- University Problems in the United States, New York, 1898

- Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville, introduction by Daniel Coit Gilman, New York, 1898

- The Life of James Dwight Dana, Scientific Explorer, Mineralogist, Geologist, Zoologist, Professor in Yale University, New York, 1899

- Memorial of Samuel de Champlain: Who Discovered the Island of Mt. Desert, Maine, September 5, 1604, Baltimore, 1904

- The Launching of a University and Other Papers, New York, 1906

Papers of Daniel Coit Gilman

editThe Papers of Daniel Coit Gilman were donated to Johns Hopkins University by Gilman's daughter Elisabeth, and are open on an unrestricted basis to the public at the Milton S. Eisenhower Library at Hopkins. Aside from many photographs of Gilman and his contemporaries, the papers include Gilman's correspondence with leading figures of the day, including Charles W. Eliot, Sidney Lanier, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry James, James Russell Lowell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William McKinley, Basil Gildersleeve, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, George Bancroft, Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Huxley, Andrew Carnegie, Horace Greeley, Helen Keller, Louis Pasteur, Henry Ward Beecher, William Osler, W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T Washington and others.[19]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Obituary: Dr. Daniel C. Gilman". Nature. 78 (2034): 641. 22 October 1908. doi:10.1038/078640a0.

- ^ "Daniel Coit Gilman". (1908/1909) Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University Deceased During the Academical Year Ending in June, 1909 (68): 1012–1017.

- ^ "Education: At Johns Hopkins". 1 March 1926. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2017 – via time.com.

- ^ William Charles Gilman, father of Daniel, and a graduate of Phillips Exeter Academy, relocated from Exeter, New Hampshire to Norwich, Connecticut in 1816, where he founded a highly successful factory to manufacture nails.The life of Daniel Coit Gilman

- ^ Exeter, New Hampshire Franklin, Fabian (1910). The Life of Daniel Coit Gilman. Harvard College Library: Dodd Mead. p. 1.

daniel coit gilman.

- ^ Fabian Franklin (1910). The Life of Daniel Coit Gilman. Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 1.

daniel coit gilman exeter new hampshire.

- ^ a b c "Daniel Coit Gilman, A Biography; Fabian Franklin Tells the Life Story of a Great Educational Organizer and Administrator" (PDF). The New York Times. May 21, 1910. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ Andrew Delbanco, "The Decline and Fall of Literature". The New York Review of Books, 4 November 1999

- ^ "MemberListG". Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ a b New Century Reference Library, 1907

- ^ "Henry Codman Potter". Proceedings of the Trustees of the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen (Report). Vol. 40. New York: John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen. 1908. pp. 12–14. hdl:2027/coo.31924093254153.

- ^ Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ Carnegie Institution of Washington. Year Book No. 47, July 1, 1947 – June 30, 1948 (PDF). Washington, DC. 1948. p. vi.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Polly M. Rettig and S. S. Bradford (March 8, 1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Daniel Coit Gilman Summer Home; "Over Edge"" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-06-22. and Accompanying photos, exterior, undated (137 KB)

- ^ Frost, John. "The Library Conference of '53." The Journal of Library History (1966–1972) 2, no. 2 (1967): 154–60.

- ^ John Mark Glenn papers, 1890–1958 (John Glenn was the first person to head the Russell Sage Foundation.)

- ^ "Glenn, Mary Wilcox - Social Welfare History Project". 11 February 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ "Daniel Coit Gilman Papers, The Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University". Retrieved 18 Oct 2022.

Further reading

edit- Francesco Cordasco (1973). The Shaping of American Graduate Education: Daniel Coit Gilman and the Protean Ph.D. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0874711614.

- Jarrett, William H. (2011). "Yale, Skull and Bones, and the Beginnings of Johns Hopkins". Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 24 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1080/08998280.2011.11928679. PMC 3012287. PMID 21307974.

- Benson, Michael T. (2022). Daniel Coit Gilman and the Birth of the American Research University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9781421444161.

External links

edit- Works by Daniel Coit Gilman at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Daniel Coit Gilman at the Internet Archive

- Daniel Coit Gilman papers – Finding aid for collection of Gilman papers at the Johns Hopkins University

- A Historical Discourse Delivered in Norwich, Connecticut, September 7, 1859, Bi-Centennial Celebration of the Settlement of the Town, Daniel Coit Gilman, Printed by George C. Rand & Avery, Boston, Mass., 1859

- Daniel Coit Gilman at Find a Grave

- Statue of Daniel Coit Gilman, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, monumentcity.org

- The Building of the University, An Inaugural Address, Delivered at Oakland, Nov. 7th, 1872, Daniel C. Gilman, President of the University of California

- The Graves-Gilman House, New Haven, Connecticut, Historic Buildings of Connecticut

- Daniel Coit Gilman HIstoric Marker, Bolton HIll Historic District, Baltimore, Maryland

- Inaugural Address of Daniel Coit Gilman as First President of Johns Hopkins University, February 22, 1876