Winslow Hall is a country house, now in the centre of the small town of Winslow, Buckinghamshire, England. Built in 1700, it was sited in the centre of the town, with a public front facing the highway and a garden front that still commanded 22 acres (89,000 m2) in 2007, due to William Lowndes' gradual purchase of a block of adjacent houses and gardens from 1693 onwards.[2][3] The architect of the mansion has been a matter of prolonged architectural debate; the present candidates are Sir Christopher Wren or a draughtsman, whether in the Board of Works, which Wren oversaw, or a talented provincial architect.

| Winslow Hall | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Queen Anne |

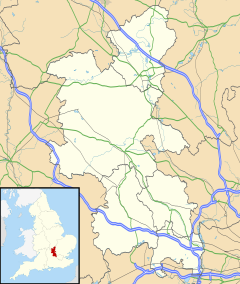

| Location | Winslow, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Coordinates | 51°56′29″N 0°52′48″W / 51.9415°N 0.8800°W |

| Completed | 1700 |

| Client | William Lowndes |

| Owner | The Hon. Christopher and Mardi Gilmour[1] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 2 |

Architect

edit"Winslow Hall was built in 1700 by Secretary Lowndes", claims Kip and Knyff's Britannia Illustrata (1708), with no mention of an architect. Winslow Hall was probably designed by Sir Christopher Wren, according to Howard Colvin,[4] who found the case not proved. George Lipscomb was less cautious: he notes the "commodious plain brick edifice with a flight of several steps to the door over which is the date of its erection 1700 and the name of William Lowndes" and adds confidently, "for whom it was designed by Inigo Jones".[5] Inigo Jones died in 1652, and so is unlikely to have designed Winslow. Pevsner too feels the house was in "all probability" designed by Wren.[6]

Sir Christopher Wren is thoroughly plausible – in a ledger book discovered in the early twentieth century detailing work on the house, scattered among the payments made to stonemasons and bricklayers, and for the carpentry to Matthew Banckes, are alterations in payments to craftsmen, authorised by 'St. Critophr Wren Surveior Gen' [sic] The account book is complete and detailed and yet records no payment to Sir Christopher Wren himself. William Lowndes (the owner) and Wren knew each other, they served on a committee together in 1704. All Souls College, Oxford owned a three-volume collection of architectural drawings by Wren, although most pertain to the plans for St Paul's cathedral there are also sketches and plans for his domestic buildings - there is nothing resembling Winslow Hall or anything there to suggest that Wren was the architect.[7]

The master carpenter documented at the house was Matthew Banckes, who had been Master Carpenter in the Office of Works since 1683, and was Master of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters at the time the house was built. Banckes often acted as surveyor at works by Wren, including six of the City churches and at Trinity College Library, Cambridge.

The fireplaces on the ground floor are no longer original, but one room on the first floor retains an original corner fireplace. Corner fireplaces are said to have been a feature of Wren's domestic work. However, they consequently became a fashion at the time. The four massive chimney stacks, dominating the mansion, are not repeated on any house designed by Wren. While in the ledger book is recorded the most menial labourer's name to the highest surveyor's, never once is the architect mentioned. A 1695 engraving of Sarsden House, Sarsden, Oxfordshire, shows a very similar house to Winslow.[8]

As happened the length and breadth of England it is likely that similar projects were copied by a local draughtsman, and in the case of Winslow Hall, Wren kept an eye on the work and the books as a favour to his friend. Whatever the truth, it is doubtful three hundred years later a definite answer to the architect's identity will be found. Thus without stronger evidence, while it is probable Wren was involved, Winslow Hall can only be attributed to Sir Christopher Wren. If the house is by Wren, it is the only surviving example of a substantially unaltered Wren House outside London.[9]

Design and grounds

editThe design concept is extreme symmetry, pushed to the utmost extent. The original plan of the house was very simple, a main rectangular block, three floors high, 7 bays long, 5 bays wide. The fenestration is of symmetrically placed sash windows. The three bayed central section is crowned on both principal facades by a pediment containing a round window. The central front door led to a narrow passage the width of the house ending with a door onto the garden at the rear. To the right at the front was the dining room, to the left the hall. Passing along the passage, towards the gardens, were on the right the library and on the left the withdrawing room. Symmetrically placed in the center of each end wall of the house were staircases.

Flanking the house were two wings, on the west a large kitchen and service range and on the east connected by a covered way a brew-house and laundry. These two wings have now been altered and in one case removed. The interiors of the house have too been altered over the centuries, however much original panelling remains.

It is recorded that the builders used in all 111 oak trees which cost a total of £221:19s:2d. The bill for cutting "Mr Lowndes name and the date of the year over the door" ('1700', and visible from the road today) was £5. The total cost of building the house was £6,585:10shillings and 2.25pence.[10]

The South (entrance front) faces the main A413 road from Aylesbury to Buckingham and is within a few metres and clearly visible from the road, something very rare in an English country house, one other instance where this happens is Aynhoe Park in Northamptonshire. William Lowndes bought his original house in 1685, and gradually acquired his neighbours' properties during the 1690s, e.g. "a brick house standing near the street pulled down to build my new house", and demolished houses on the other side of the road to improve the view.[11] Hence Winslow Hall is almost unique as both a town and a country house. Thus it is even more remarkable that it has survived largely unaltered, escaped conversion to institutional or office use, and remains today (2014) an inhabited house.

Occupational history

editThe house was occupied by William Lowndes and his family until his death in 1724, and continued to be occupied by his descendants until 1848, when it became Dr Lovell's School (previously located in Germany).[12] Unusually, for the era, the boarding school was co-educational, housing 32 boarders. The school moved to Aspley Guise in 1862. From 1865 to 1868 Dr Theodore Boisragon used the house as a private asylum for lunatics.[13] It was then let until it was sold to Brigadier Norman McCorquodale in 1898. In 1942, the mansion was purchased by the Northampton Glass Bottle company, but requisitioned for war use, it became the offices of RAF Bomber Command for the duration of the Second World War, following which it was left in poor condition.

The house was Grade 1 listed in 1946, but was bought by contractors for £8,000 in 1947 and, like many country houses, came under threat of demolition. Reprieved, it was bought by Geoffrey Houghton-Brown, and became an antiques showroom.[9] The house again changed hands in 1959 and was bought by diplomat Sir Edward Tomkins. Tomkins and his wife restored the house and improved the 5 acres (20,000 m2) of garden to the rear (south) by planting specimen trees and shrubs.

Sir Edward offered Winslow Hall for sale in May 2007, just four months before his death. The architectural commentator Marcus Binney reporting the sale of the "ultimate trophy house" and surroundings 22 acres (89,000 m2), in The Times, attributed the design of the house to Wren without any reference to the doubt concerning the architect.[14]

Binney also commented on the unchanged interior which included the possibility that the largest room in the house the second floor gallery would be suitable for conversion to a private cinema, and a caveat on the mansion insisting that the chapel and priest's house attached to the house were let to the Roman Catholic Church. However, Binney, while commenting on the unchanged interior, remarked on the cabinets converted to bathrooms, and ignores the rooms which have been combined to create larger reception rooms. However, these changes were described in 1926 as a "small amount of alteration".[15]

In all the house was offered for sale consisting of six bedroom suites, two self contained flats and surrounded by 22 acres (89,000 m2) of land. Much of this land is agricultural pasture land across the road from the house, thus the house's setting, surrounded by other houses in close proximity is urban rather than rural.[16]

In October 2007 there was speculation in the British press that the house was to be purchased by the former prime minister Tony Blair.[17] However, the exposed and highly visible location of the mansion (both neighbouring houses and a very busy main road are within 20 metres of the property) suggest that the security implications render the house unsuitable for a high profile public figure.

The contents of the property were sold by auction in April 2009 with an open day being held on 12 April 2009 when smaller items were offered for sale. Entry was free but donations were made to Willen Hospice for car parking.

Winslow Hall was sold on 30 June 2010 to the new owners, The Hon Christopher and Mardi Gilmour, son and daughter-in-law of the late Baron Gilmour,[18] but only moved in at the start of 2012 after much repair work.[19]

References

edit- ^ Winslow Hall: At home with the Gilmours

- ^ "Winslow Hall and the Lowndes family". Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "View of frankpledge and court baron, 17 April 1695". Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Colvin 1995, s.v. Matthew Banckes, Sir Christopher Wren, based on material presented in The Wren Society, xvii, 54-75.

- ^ George Lipscomb (1847). The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham. J. & W. Robins.

- ^ Pevsner, p 297

- ^ Records of Buckinghamshire, p 407

- ^ Sarsden House, the seat of Sir John Walter, 3rd Bt. (c 1674—1722), Tory M.P, who succeeded his father in 1694 (David Hayton, Eveline Cruickshanks, Stuart Handley, eds. The House of Commons, 1690-1715, Vol.1, s.v. "Walter, Sir John, 3rd Bt.") appears in a 1695 engraving by Michael Burgers, illustrated in Colin Platt, The Great Rebuildings of Tudor and Stuart England: revolutions in architectural taste 1994, p. 161 fig. 68; it is in four ranges round a central court, with wing extensions; its entrance front of seven bays has a slightly projecting three-bay central block under a pediment flanked by attic dormers, with a similar dentilled cornice and similar small-scaled quoins at all corners.

- ^ a b Penny Churchill (10 May 2007). "For Sale: Winslow Hall". Country Life.

- ^ All figures and statistics in this section are from Records of Buckinghamshire

- ^ "Lowndes Roll 1". Winslow History. 10 December 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Dr Lovell's school at Winslow Hall". Winslow History. 28 April 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Winslow Hall Asylum (1865-8)". Winslow History. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "The ultimate trophy house". The Times. 11 May 2007. Bricks and Mortar Supplement, p 15

- ^ Records of Buckinghamshire, p 409 & p 429.

- ^ Pevsner, p 298 describes the house as both "urban" and "metropolitan".

- ^ Gordon Rayner; Anna Tyzack (11 October 2007). "Inside the Blairs' 'new home' at Winslow Hall". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Town's big day out fields sunny smiles". Buckingham and Winslow Advertiser. 2 September 2010.

- ^ Nick Curtis (24 July 2012). "Let's put on an opera right here!". London Evening Standard.

Notes

edit- Records of Buckinghamshire, Vol. XIm No. 7; published by The Society, Aylesbury, 1926

- Colvin, Howard, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600-1840 3rd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press) 1995: s.v."Matthew Banckes", "Sir Christopher Wren"

- Nikolaus Pevsner (1960). Buckinghamshire. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071019-1.