Ruyijun zhuan (如意君傳),[a] translated into English as The Lord of Perfect Satisfaction,[2][3][4] is a Chinese erotic novella written in the Ming dynasty by an unknown author. Set in the Tang dynasty, it follows the political career and love life of Empress Wu Zetian. One of the earliest erotic novels published in China, it was repeatedly banned after its publication.

| Original title | 如意君傳 |

|---|---|

| Translator | Charles Stone |

| Language | Chinese |

Publication date | Early 16th-century |

| Publication place | China (Ming dynasty) |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 45 |

| Ruyijun zhuan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 如意君傳 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 如意君传 | ||||||

| |||||||

Plot

editAt age fourteen, Wu Zetian becomes one of Emperor Tang Taizong's minor concubines. Some twelve years later, the emperor falls gravely ill; while tending to her husband at his deathbed, Wu makes love with the crown prince Tang Gaozong.[5] Upon Taizong's death, however, Wu is forced to become a Buddhist nun along with the other royal spouses.[5] She is rescued by Gaozong a year later and becomes his wife. Following his death seven years later, she rises through the ranks and becomes the first and only female emperor of China after demoting the crown prince, Tang Zhongzong.[6][7]

Dissatisfied with her present sexual partners, Wu, who at this point is a septuagenarian, summons an aide to bring her a Luoyang virgin named Xue Aocao (薛敖曹),[b] who is rumoured to be extremely well-endowed.[9] After personally examining his penis, Wu has sex with Xue;[10] she names him the "Lord of Perfect Satisfaction"[11] and renames the calendar year the "First Year of Perfect Satisfaction".[12] Xue becomes her favourite lover and she dismisses her other consorts.[13] After threatening to castrate himself, Xue successfully convinces her to return the throne to Zhongzong.[14] As Wu's health declines,[15] her romantic relationship with Xue comes to an end, and they bid each other farewell in a complex ritual involving the burning of genitals with ambergris[16] and the reenactment of various sexual positions ten times each.[7] Xue disappears and is reportedly sighted in Chengdu as an immortal many years later.[17]

Composition

editRuyijun zhuan chronicles Wu Zetian's rise to power while detailing her numerous sexual encounters,[5] especially with the male protagonist Xue Aocao.[4][18] The title refers to Xue,[19] a thirty-year-old virgin[19] who is conferred the title of "Ruyijun" or "Lord of Perfect Satisfaction" by Empress Wu Zetian.[19][20] Apart from Xue Aocao, all of the empress' lovers depicted in Ruyijun zhuan are historical figures.[4] Ruyijun zhuan "barely amounts to forty-five pages"[21] and was predominantly written in Classical Chinese,[22] interspersed with some vernacular Chinese dialogue.[4] It extensively quotes from and alludes to notable works like the Records of the Grand Historian, the Mencius, the Analects, the Classic of Poetry, and the I Ching.[23] Ruyijun zhuan also contains extensive descriptions of genitalia which do "not appear to be conducive to the stimulation of lewd desires"; for instance, Xue Aocao's penis is compared with snails and earthworms,[20] while Wu Zetian's cervix is written to be "like a flower pistil enveloped by a calyx beginning to frondesce".[20]

Publication history

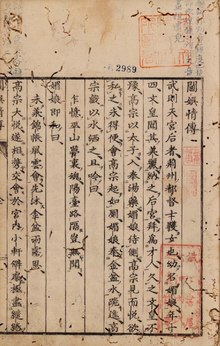

editAccording to Liu Hui, the preface and postscript of the novella are dated 1514 and 1520 respectively, suggesting that the story itself was written sometime in between.[24] However, Charles Stone, who published an English translation and critical study of Ruyijun zhuan, dates the novella to between 1524 and 1529, and argues that its preface and postscript were likely written in 1634 and 1760 respectively. Stone argues that the Ryuijun zhuan was written by the scholar and civil servant Huang Xun (黃訓; 1490–c.1540),[24][25] who made what is believed to be the earliest known reference to Ruyijun zhuan in a three-page-long essay published between 1525 and 1540.[24][26] Ruyijun zhuan was repeatedly banned after its publication.[19] An abridged version of the story, titled Wu Zhao zhuan (武曌傳) or The Story of Empress Wu Zhao, was published around 1587;[27] it omits all the poetry and allusions found in the original text, while presenting a much shorter cast of characters.[28] Having previously been circulated as a manuscript, the earliest printed edition of Ruyijun zhuan was published in 1763[29] by Tokyo-based publisher Ogawa Hikokurô.[30]

Literary significance and influence

editRuyijun zhuan is one of the earliest erotic books published in China,[31][32] and is seen by some scholars as the first pornographic novel written in Chinese.[33] Charles Stone writes that "most Chinese erotic fiction written during the next hundred years was ultimately inspired by the Ruyijun zhuan or borrowed from its vocabulary."[34] Alongside Chipozi zhuan (癡婆子傳; The Story of the Foolish Woman) and Xiuta yeshi (繡榻野史; The Embroidered Couch), Ruyijun zhuan is one of the three erotic works referenced in The Carnal Prayer Mat believed to have been written by Qing dynasty writer Li Yu.[2] About three hundred years after the original Ruyijun zhuan was published, Chen Tianchi (陳天池) wrote an erotic novel with the same title; the Qing dynasty Ruyijun zhuan follows a well-endowed male protagonist who curries favour with three emperors of the Ming dynasty and later becomes an immortal.[19]

The Sui Tang liangchao shizhuan (隋唐兩朝志傳; 1619)[35] or Historical Record of the Sui and Tang Dynasties copies a number of pages from Ruyijun zhuan word-for-word.[36] Similarly, the Nongqing kuaishi (濃情快史; 1712)[37] or Heart-throbbing History of Powerful Passions plagiarises much of the original Ruyijun zhuan,[34] but omits "inappropriate references that detract from the portrayal of sex".[27]

Notes

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ Stevenson & Wu 2017, p. 14.

- ^ a b Hanan 1988, p. 123.

- ^ Huang 2004, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d e Lo 2005, p. 331.

- ^ a b c Stone 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 2.

- ^ a b McMahon 2013, p. 201.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 141.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 144.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 147.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 151.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 55.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 157.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 158.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 160.

- ^ Epstein 2005, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d e Huang 2004, p. 196.

- ^ a b c Stone 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 120.

- ^ McMahon 1987, p. 224.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Huang 2004, p. 203.

- ^ Stone 2003, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 57.

- ^ a b Lo 2005, p. 332.

- ^ Stone 2003, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 107.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 216.

- ^ McMahon 1987, p. 222.

- ^ Huang 2020, p. 114.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 13.

- ^ a b Stone 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 119.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 116.

- ^ Stone 2003, p. 117.

Bibliography

edit- Epstein, Maram (February 2005). "Reviewed Work: The Fountainhead of Chinese Erotica: The Lord of Perfect Satisfaction (Ruyijun zhuan) by Charles R. Stone". The Journal of Asian Studies. 64 (1). Association for Asian Studies: 179–181. doi:10.1017/S0021911805000252. JSTOR 25075696. S2CID 163654561.

- Hanan, Patrick (1988). The Invention of Li Yu. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674464254.

- Huang, Martin W. (2004). Snakes' Legs: Sequels, Continuations, Rewritings, and Chinese Fiction. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824864330.

- Huang, Martin W. (2020). Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Brill. doi:10.1163/9781684173570. ISBN 9781684173570.

- Lo, Andrew (2005). "Reviewed Work: The Fountainhead of Chinese Erotica: "The Lord of Perfect Satisfaction (Ruyijun zhuan)", with a Translation and Critical Edition by Charles R. Stone". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 68 (2). Cambridge University Press: 331–333. doi:10.1017/S0041977X05310159. JSTOR 20181933. S2CID 162443681.

- McMahon, Keith (1987). "Eroticism in Late Ming, Early Qing Fiction: The Beauteous Realm and the Sexual Battlefield". T'oung Pao. 73 (4/5). Brill: 217–264. doi:10.1163/156853287X00032. JSTOR 4528390. PMID 11618220.

- McMahon, Keith (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442222908.

- Stevenson, Mark; Wu, Cuncun (2017). Wanton Women in Late-Imperial Chinese Literature: Models, Genres, Subversions and Traditions. Brill. ISBN 9789004340626.

- Stone, Charles R. (2003). The Fountainhead of Chinese Erotica: The Lord of Perfect Satisfaction (Ruyijun zhuan), with a Translation and Critical Edition. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824862589.