Odisha (English: /əˈdɪsə/;[19] Odia: [oɽiˈsa] ⓘ), formerly Orissa (the official name until 2011),[20] is a state located in Eastern India. It is the eighth-largest state by area, and the eleventh-largest by population, with over 41 million inhabitants. The state also has the third-largest population of Scheduled Tribes in India.[21] It neighbours the states of Jharkhand and West Bengal to the north, Chhattisgarh to the west, and Andhra Pradesh to the south. Odisha has a coastline of 485 kilometres (301 mi) along the Bay of Bengal in the Indian Ocean.[22] The region is also known as Utkaḷa and is mentioned by this name in India's national anthem, Jana Gana Mana.[23] The language of Odisha is Odia, which is one of the Classical languages of India.[24]

The ancient kingdom of Kalinga, which was invaded by the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka in 261 BCE resulting in the Kalinga War, coincides with the borders of modern-day Odisha.[25] The modern boundaries of Odisha were demarcated by the British Indian government, the Orissa Province was established on 1 April 1936, consisting of the Odia-speaking districts of Bihar and Orissa Province, Madras Presidency and Central Provinces.[25] Utkala Dibasa (lit. 'Odisha Day') is celebrated on 1 April.[26] Cuttack was made the capital of the region by Anantavarman Chodaganga in c. 1135,[27] after which the city was used as the capital by many rulers, through the British era until 1948. Thereafter, Bhubaneswar became the capital of Odisha.[28]

The economy of Odisha is the 15th-largest state economy in India with ₹5.86 trillion (US$69 billion) in gross domestic product and a per capita GDP of ₹127,383 (US$1,500).[8] Odisha ranks 32nd among Indian states in Human Development Index.[29]

Etymology

editThe terms Odisha and Orissa (Odia: ଓଡ଼ିଶା, Oṛissa) derive from the ancient Prakrit word "Odda Visaya" (also "Udra Bibhasha" or "Odra Bibhasha") as in the Tirumalai inscription of Rajendra Chola I, which is dated to 1025.[30] Sarala Das, who translated the Mahabharata into the Odia language in the 15th century, calls the region 'Odra Rashtra' as Odisha. The inscriptions of Kapilendra Deva of the Gajapati Kingdom (1435–67) on the walls of temples in Puri call the region Odisha or Odisha Rajya.[31]

In 2011, the English rendering of ଓଡ଼ିଶା was changed from "Orissa" to "Odisha", and the name of its language from "Oriya" to "Odia", by the passage of the Orissa (Alteration of Name) Bill, 2010 and the Constitution (113th Amendment) Bill, 2010 in the Parliament. The Hindi rendering उड़ीसा (uṛīsā) was also modified to ओड़िशा (or̥iśā). After a brief debate, the lower house, Lok Sabha, passed the bill and amendment on 9 November 2010.[32] On 24 March 2011, Rajya Sabha, the upper house of Parliament, also passed the bill and the amendment.[33] The changes in spelling were made with the intention of having the English and Hindi renditions conform to the Odia transliteration.[34] However, the underlying Odia texts were nevertheless transliterated incorrectly as per the Hunterian system, the official national transliteration standard, in which the transliterations would be Orisha and Oria instead.

History

editPrehistoric Acheulian tools dating to Lower Paleolithic era have been discovered in various places in the region, implying an early settlement by humans.[35] Kalinga has been mentioned in ancient texts like Mahabharata, Vayu Purana and Mahagovinda Suttanta.[36][37]

According to political scientist Sudama Misra, the Kalinga janapada originally comprised the area covered by the Puri and Ganjam districts.[38] The Sabar people of Odisha have also been mentioned in the Mahabharata.[39][40] Baudhayana mentions Kalinga as not yet being influenced by Vedic traditions, implying it followed mostly tribal traditions.[41]

Ashoka of the Mauryan dynasty conquered Kalinga in the bloody Kalinga War in 261 BCE,[42] which was the eighth year of his reign.[43] According to his own edicts, in that war about 100,000 people were killed, 150,000 were captured and more were affected.[42] The resulting bloodshed and suffering of the war is said to have deeply affected Ashoka. He turned into a pacifist and converted to Buddhism.[43][44]

By c. 150 BCE, Emperor Kharavela, who was possibly a contemporary of Demetrius I of Bactria,[45] conquered a major part of the Indian sub-continent. Kharavela was a Jain ruler. He also built the monastery atop the Udayagiri hill.[46] Subsequently, the region was ruled by monarchs, such as Samudragupta[47] and Shashanka.[48] It was also a part of Harsha's empire.[49]

The city of Brahmapur in Odisha is also known to have been the capital of the Pauravas during the closing years of 4th century CE. Nothing was heard from the Pauravas from about the 3rd century CE, because they were annexed by the Yaudheya Republic, who in turn submitted to the Mauryans. It was only at the end of 4th century CE, that they established royalty at Brahmapur, after about 700 years.

Later, the kings of the Somavamsi dynasty began to unite the region. By the reign of Yayati II, c. 1025 CE, they had integrated the region into a single kingdom. Yayati II is supposed to have built the Lingaraj temple at Bhubaneswar.[25] They were replaced by the Eastern Ganga dynasty. Notable rulers of the dynasty were Anantavarman Chodaganga, who began reconstruction on the present-day Shri Jagannath Temple in Puri (c. 1135), and Narasimhadeva I, who constructed the Konark temple (c. 1250).[50][51]

The Eastern Ganga Dynasty was followed by the Gajapati Kingdom. The region resisted integration into the Mughal empire until 1568, when it was conquered by Sultanate of Bengal.[52] Mukunda Deva, who is considered the last independent king of Kalinga, was defeated and was killed in battle by a rebel Ramachandra Bhanja. Ramachandra Bhanja himself was killed by Bayazid Khan Karrani.[53] In 1591, Man Singh I, then governor of Bihar, led an army to take Odisha from the Karranis of Bengal. They agreed to treaty because their leader Qutlu Khan Lohani had recently died. But they then broke the treaty by attacking the temple town of Puri. Man Singh returned in 1592 and pacified the region.[54]

In 1751, the Nawab of Bengal Alivardi Khan ceded the region to the Maratha Empire.[25]

The British had occupied the Northern Circars, comprising the southern coast of Odisha, as a result of the Second Carnatic War by 1760, and incorporated them into the Madras Presidency gradually.[55] In 1803, the British ousted the Marathas from the Puri-Cuttack region of Odisha during the Second Anglo-Maratha War. The northern and western districts of Odisha were incorporated into the Bengal Presidency.[56]

The Orissa famine of 1866 caused an estimated 1 million deaths.[57] Following this, large-scale irrigation projects were undertaken.[58] In 1903, the Utkal Sammilani organisation was founded to demand the unification of Odia-speaking regions into one state.[59] On 1 April 1912, the Bihar and Orissa Province was formed.[60] On 1 April 1936, Bihar and Orissa were split into separate provinces.[61] The new province of Orissa came into existence on a linguistic basis during the British rule in India, with Sir John Austen Hubback as the first governor.[61][62] Following India's independence, on 15 August 1947, 27 princely states signed the document to join Orissa.[63] Most of the Orissa Tributary States, a group of princely states, acceded to Orissa in 1948, after the collapse of the Eastern States Union.[64]

Geography

editOdisha lies between the latitudes 17.780N and 22.730N, and between longitudes 81.37E and 87.53E. The state has an area of 155,707 km2, which is 4.87% of total area of India, and a coastline of 450 km.[65] In the eastern part of the state lies the coastal plain. It extends from the Subarnarekha River in the north to the Rushikulya River in the south. The lake Chilika is part of the coastal plains. The plains are rich in fertile silt deposited by the six major rivers flowing into the Bay of Bengal: Subarnarekha, Budhabalanga, Baitarani, Brahmani, Mahanadi, and Rushikulya.[65] The Central Rice Research Institute (CRRI), a Food and Agriculture Organization-recognised rice gene bank and research institute, is situated on the banks of Mahanadi in Cuttack.[66] The stretch between Puri and Bhadrak in Odisha juts out a little into the sea, making it vulnerable to any cyclonic activity.[67]

Three-quarters of the state is covered in mountain ranges. Deep and broad valleys have been made in them by rivers. These valleys have fertile soil and are densely populated. Odisha also has plateaus and rolling uplands, which have lower elevation than the plateaus.[65] The highest point in the state is Deomali at 1,672 metres in Koraput district. Some other high peaks are: Sinkaram (1,620 m), Golikoda (1,617 m), and Yendrika (1,582 metres).[68]

Climate

editThe state experiences four meteorological seasons: winter (January to February), pre-monsoon season (March to May), south-west monsoon season (June to September) and north east monsoon season (October–December). However, locally the year is divided into six traditional seasons (or rutus): Grishma (summer), Barsha (rainy season), Sharata (autumn), Hemanta (dewy),Sheeta(winter season) and Basanta (spring).[65]

| Mean Temp and Precipitation of Selected Weather Stations[69] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhubaneswar (1952–2000) |

Balasore (1901–2000) |

Gopalpur (1901–2000) |

Sambalpur (1901–2000) | |||||||||

| Max (°C) | Min (°C) | Rainfall (mm) | Max (°C) | Min (°C) | Rainfall (mm) | Max (°C) | Min (°C) | Rainfall (mm) | Max (°C) | Min (°C) | Rainfall (mm) | |

| January | 28.5 | 15.5 | 13.1 | 27.0 | 13.9 | 17.0 | 27.2 | 16.9 | 11.0 | 27.6 | 12.6 | 14.2 |

| February | 31.6 | 18.6 | 25.5 | 29.5 | 16.7 | 36.3 | 28.9 | 19.5 | 23.6 | 30.1 | 15.1 | 28.0 |

| March | 35.1 | 22.3 | 25.2 | 33.7 | 21.0 | 39.4 | 30.7 | 22.6 | 18.1 | 35.0 | 19.0 | 20.9 |

| April | 37.2 | 25.1 | 30.8 | 36.0 | 24.4 | 54.8 | 31.2 | 25.0 | 20.3 | 39.3 | 23.5 | 14.2 |

| May | 37.5 | 26.5 | 68.2 | 36.1 | 26.0 | 108.6 | 32.4 | 26.7 | 53.8 | 41.4 | 27.0 | 22.7 |

| June | 35.2 | 26.1 | 204.9 | 34.2 | 26.2 | 233.4 | 32.3 | 26.8 | 138.1 | 36.9 | 26.7 | 218.9 |

| July | 32.0 | 25.2 | 326.2 | 31.8 | 25.8 | 297.9 | 31.0 | 26.1 | 174.6 | 31.1 | 24.9 | 459.0 |

| August | 31.6 | 25.1 | 366.8 | 31.4 | 25.8 | 318.3 | 31.2 | 25.9 | 195.9 | 30.7 | 24.8 | 487.5 |

| September | 31.9 | 24.8 | 256.3 | 31.7 | 25.5 | 275.8 | 31.7 | 25.7 | 192.0 | 31.7 | 24.6 | 243.5 |

| October | 31.7 | 23.0 | 190.7 | 31.3 | 23.0 | 184.0 | 31.4 | 23.8 | 237.8 | 31.7 | 21.8 | 56.6 |

| November | 30.2 | 18.8 | 41.7 | 29.2 | 17.8 | 41.6 | 29.5 | 19.7 | 95.3 | 29.4 | 16.2 | 17.6 |

| December | 28.3 | 15.2 | 4.9 | 26.9 | 13.7 | 6.5 | 27.4 | 16.4 | 11.4 | 27.2 | 12.1 | 4.8 |

Biodiversity

editAccording to a Forest Survey of India report released in 2012, Odisha has 48,903 km2 of wild forest, covering 31.41% of the state's total area. The forests are classified into areas of dense forest (7,060 km2), medium dense forest (21,366 km2), open forest (forest without closed canopy; 20,477 km2) and scrub forest or scrubland (4,734 km2). The state also has bamboo forests (10,518 km2) and tidal areas of mangrove swamp (221 km2). The state is gradually losing its wilderness areas to timber smuggling, deforestation, destructive mining, and general urban industrialisation, as well as livestock grazing. There have been attempts at conservation and reforestation.[70]

Due to the climate and good rainfall, Odisha's evergreen and moist forests are uniquely suitable habitats for wild orchids. Around 130 species have been reported from the state.[71] Around 97 of them are found in Mayurbhanj district alone. The Orchid House of the Nandankanan Zoological Park maintains some of these species.[72]

Simlipal National Park is a protected wildlife area and Bengal tiger reserve spread over 2,750 km2 of the northern part of Mayurbhanj district. The park has around 1,078 species of plants, including 94 of the aforementioned orchids. The sal is the primary tree species. For fauna, the park is home to around 55 species of mammal, including the Bengal tiger, chital, chousingha, common langur, gaur, Indian elephant, Indian giant squirrel, jungle cat, leopard, muntjac, sambar, small Indian civet and wild boar. There are over 300 species of birds in the park, such as the common hill myna, as well as grey, Indian pied and Malabar pied hornbills. There are also some 60 species of reptiles and amphibians, including the famed king cobra, plus banded krait and tricarinate hill turtle. There is also a mugger crocodile breeding programme in nearby Ramtirtha.[73]

The Chandaka Elephant Sanctuary is a 190 km2 protected area near the capital city, Bhubaneswar. However, urban expansion and over-grazing have reduced the forests, driving the herds of elephants to migrate away, as well as increasing human-elephant conflicts—which sometimes results in injury and death (on both sides). Some elephants have died in conflicts with villagers, while some have died during migration after being accidentally electrocuted by power lines or even hit by trains. Outside the protected area, they are killed by ivory poachers. In 2002, there were about 80 elephants, but by 2012, their numbers had been reduced to 20. Many of the animals have migrated toward the Barbara Reserve forest, Chilika, Nayagarh district, and Athagad.[74][75] Besides elephants, the sanctuary also has leopards, jungle cats and herds of chital.[76]

The Bhitarkanika National Park in Kendrapara district covers 650 km2, of which 150 km2 are mangroves. Gahirmatha Beach, in Bhitarkanika, is the world's largest nesting site for olive ridley sea turtles.[77] In 2013, the Indian Coast Guard initiated Operation Oliver to protect the endangered sea turtle population of the region.[78] Other major nesting grounds for the turtle in the state are Rushikulya, in Ganjam district,[79] and the mouth of the Devi river.[80] The Bhitarkanika sanctuary is also noted for its large population of saltwater crocodiles and Asian water monitors,[81] the second-largest lizard species on earth,[82] in addition to axis deer and rhesus macaques.[81] The coastal mangrove environments are home to several types of mudskippers, including the barred, Boddart's blue-spotted and great blue-spotted mudskippers.[81]

In winter, Bhitarkanika is also visited by migratory birds. Among the many species, both resident and migratory, are kingfishers (including black-capped, collared and common kingfishers), herons (such as black-crowned night, grey, purple and striated herons), Indian cormorants, openbill storks, Oriental white ibis, pheasant-tailed jacana, sarus cranes, spotted owlets and white-bellied sea-eagles.[83][81] The possibly endangered horseshoe crab is also found in this region.[84]

Chilika Lake is a brackish water lagoon on the east coast of Odisha with an area of 1,105 km2. It is connected to the Bay of Bengal by a 35-km-long narrow channel and is a part of the Mahanadi delta. In the dry season, the tides bring in salt water. In the rainy season, the rivers falling into the lagoon decrease its salinity.[85] Birds from places as far as the Caspian Sea, Lake Baikal (and other parts of Russia), Central Asia, Southeast Asia, Ladakh and the Himalayas migrate to the lagoon in winter.[86] Among the waterfowl and wading birds spotted there are Eurasian wigeon, pintail, bar-headed goose, greylag goose, greater flamingo, common mallard and Goliath heron.[87][88] The lagoon also has a small population of the endangered Irrawaddy dolphins.[89] The state's coastal region has also had sightings of the rare finless porpoise, as well as the more common bottlenose dolphin, humpback dolphin and spinner dolphins in its waters.[90]

Satapada is situated close to the northeast cape of Chilika Lake and Bay of Bengal. It is famous for dolphin watching in their natural habitat. There is a tiny island en route for watching dolphins, where tourists often take a short stop. Apart from that, this island is also home for tiny red crabs.[91]

According to a census conducted in 2016, there are around 2000 elephants in the state. [92]

-

White tiger in the Nandankanan Zoo

-

Irrawaddy dolphins can be found in Chilika

-

Vanda tessellata, one of the orchids found in Odisha[93]

-

Migratory birds at Chilika Lake

-

Crocodile in Bhitarkanika National Park

Government and politics

editAll states in India are governed by a parliamentary system of government based on universal adult franchise.[94][95]

The main parties active in the politics of Odisha are the Biju Janata Dal, the Indian National Congress and Bharatiya Janata Party. Following the Odisha State Assembly Election in 2019, the Naveen Patnaik-led Biju Janata Dal stayed in power for the sixth consecutive term until 2024.[96] Currently, BJP , who won for the first time, formed the government after winning the majority in 2024 Odisha Legislative Assembly election. He is the 17th Chief Minister of Odisha.[97]

Legislative assembly

editThe Odisha state has a unicameral legislature.[98] The Odisha Legislative Assembly consists of 147 elected members,[96] and special office bearers such as the Speaker and Deputy Speaker, who are elected by the members. Assembly meetings are presided over by the Speaker, or by the Deputy Speaker in the Speaker's absence.[99] Executive authority is vested in the Council of Ministers headed by the Chief Minister, although the titular head of government is the Governor of Odisha. The governor is appointed by the President of India. The leader of the party or coalition with a majority in the Legislative Assembly is appointed as the Chief Minister by the governor, and the Council of Ministers are appointed by the governor on the advice of the Chief Minister. The Council of Ministers reports to the Legislative Assembly.[100] The 147 elected representatives are called Members of the Legislative Assembly, or MLAs. One MLA may be nominated from the Anglo-Indian community by the governor.[101] The term of the office is for five years, unless the Assembly is dissolved prior to the completion of the term.[99]

The judiciary is composed of the Odisha High Court, located at Cuttack, and a system of lower courts.

Subdivisions

editOdisha has been divided into 30 districts. These 30 districts have been placed under three different revenue divisions to streamline their governance. The divisions are North, Central and South, with their headquarters at Sambalpur, Cuttack and Berhampur respectively. Each division consists of ten districts and has as its administrative head a Revenue Divisional Commissioner (RDC).[102] The position of the RDC in the administrative hierarchy is that between that of the district administration and the state secretariat.[103] The RDCs report to the Board of Revenue, which is headed by a senior officer of the Indian Administrative Service.[102]

| Northern Division (HQ – Sambalpur) | Central Division (HQ – Cuttack) | Southern Division (HQ – Berhampur) |

|---|---|---|

Each district is governed by a collector and district magistrate, who is appointed from the Indian Administrative Service or a very senior officer from Odisha Administrative Service.[105][106] The collector and district magistrate is responsible for collecting the revenue and maintaining law and order in the district. Each district is separated into sub-divisions, each governed by a sub-collector and sub-divisional magistrate. The sub-divisions are further divided into tahasils. The tahasils are headed by tahasildar. Odisha has 58 sub-divisions, 317 tahasils and 314 blocks.[104] Blocks consists of Panchayats (village councils) and town municipalities.

The capital of the state is Bhubaneswar and the largest city is Cuttack, which also functions as the deputy capital of the state . The other major cities are, Rourkela, Berhampur and Sambalpur. Municipal Corporations in Odisha include Bhubaneswar, Cuttack, Berhampur, Sambalpur and Rourkela.

Other municipalities of Odisha include Angul, Asika, Balangir, Balasore, Barbil, Bargarh, Baripada, Basudevpur, Belpahar, Bhadrak, Bhanjanagar, Bhawanipatna, Biramitrapur, Boudh, Brajarajnagar, Byasanagar, Chhatrapur, Deogarh, Dhamra,Dhenkanal, Gopalpur, Gunupur, Hinjilicut, Jagatsinghpur, Jajpur, Jeypore, Jharsuguda, Joda, Kendrapara, Kendujhar, Khordha, Konark, Koraput, Malkangiri, Nabarangpur, Nayagarh, Nuapada, Paradeep, Paralakhemundi, Phulbani, Puri, Rajgangpur, Rayagada, Sonepur, Sundargarh, Talcher, Titilagarh, Karanjia, Chatrapur, Asika, Kantabanji, Nimapada, Baudhgarh, and Umerkote.

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuttack Bhubaneswar |

1 | Cuttack | Cuttack | 921,321 | Rourkela Brahmapur | ||||

| 2 | Bhubaneswar | Khordha | 881,988 | ||||||

| 3 | Rourkela | Sundargarh | 552,970 | ||||||

| 4 | Brahmapur | Ganjam | 355,823 | ||||||

| 5 | Sambalpur | Sambalpur | 270,331 | ||||||

| 6 | Puri | Puri | 201,026 | ||||||

| 7 | Balasore | Balasore | 144,373 | ||||||

| 8 | Bhadrak | Bhadrak | 121,338 | ||||||

| 9 | Baripada | Mayurbhanj | 116,874 | ||||||

| 10 | Balangir | Balangir | 98,238 | ||||||

Auxiliary authorities known as panchayats, for which local body elections are regularly held, govern local affairs in rural areas.

Economy

editMacro-economic trend

editOdisha is experiencing a rapid economic growth post-Covid. The impressive growth in gross domestic product of the state has been reported by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Odisha's growth rate is above the national average.[107] The central Government's Urban Development Ministry has recently announced the names of 20 cities selected to be developed as smart cities. The state capital Bhubaneswar is the first city in the list of smart Cities released in January 2016, a pet project of the Indian Government. The announcement also marked with sanction of Rs 508.02 billion over the five years for development.[108]

Industrial development

editOdisha has abundant natural resources and a large coastline. Odisha has emerged as the most preferred destination for overseas investors with investment proposals.[109] It contains a fifth of India's coal, a quarter of its iron ore, a third of its bauxite reserves and most of the chromite.

Rourkela Steel Plant[110] was the first integrated steel plant in the public sector in India, built with collaboration of Germany.

Arcelor-Mittal has also announced plans to invest in another mega steel project amounting to $10 billion. Russian major Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Company (MMK) plans to set up a 10 MT steel plant in Odisha, too. Nippon Steel Corporation has recently announced to set up their own plants, one of which will be the world's largest and most advanced steel plant in Odisha, with a production capacity of 30 MT annually.[111] Bandhabahal is a major area of open cast coal mines in Odisha. The state is attracting an unprecedented amount of investment in aluminium, coal-based power plants, petrochemicals, and information technology as well. In power generation, Reliance Power (Anil Ambani Group) is putting up the world's largest power plant with an investment of US$13 billion at Hirma in Jharsuguda district.[112]

In 2009 Odisha was the second top domestic investment destination with Gujarat first and Andhra Pradesh in third place according to an analysis of ASSOCHAM Investment Meter (AIM) study on corporate investments. Odisha's share was 12.6 per cent in total investment in the country. It received an investment proposal worth ₹2.01 trillion (equivalent to ₹4.5 trillion or US$53 billion in 2023) in 2010. Steel and power were among the sectors which attracted maximum investments in the state.[113]

The recently concluded Make in Odisha Conclave 2022 saw the state generate investment proposals worth ₹10.5 trillion with an employment potential for 10,37,701 people. Out of the total investment proposals received, the metals, ancillary and downstream sectors fetched ₹5.50 lakhs crore (trillion), power, green energy, and renewable energy sector fetched ₹2.38 trillion, and chemicals-petrochemicals and logistics-infrastructure sector attracted ₹76,000 crores and ₹1.20 trillion, respectively. Odisha has the potential to become a trillion-dollar economy by 2030.

Transportation

editOdisha has a network of roads, railways, airports and seaports. Bhubaneswar is well connected by air, rail and road with the rest of India. Some highways are getting expanded to four lanes.[114][115] Odisha Government Plans Mega Metro Rail Project to Connect Puri and Bhubaneswar [116] The metro rail proposal was given to connect trains between Puri- Bhubaneswar – Cuttack.[117] The Odisha government has planned a new Expressway that will connect Biju Patnaik International Airport airport at Bhubaneswar with the proposed Shri Jagannath International Airport at Puri.[118]

Air

editOdisha has a total of three operational airports, 16 airstrips and 16 helipads.[119][120][121] The airport at Jharsuguda was upgraded to a full-fledged domestic airport in May 2018. Rourkela Airport became operational in December 2022.The Dhamra Port Company Limited plans to build Dhamra Airport 20 km from Dhamra Port.[122]

- Bhubaneswar – Biju Patnaik International Airport

- Jeypore – Jeypore Airport

- Jharsuguda – Veer Surendra Sai Airport

- Rourkela – Rourkela Airport

- Berhampur – Rangeilunda Airport

- Bhawanipatna - Utkela Airport

Seaports

editOdisha has a coastline of 485 kilometres (301 mi). It has one major port at Paradip and few minor ports. some of them are:[123][124]

Railways

editMajor cities of Odisha are well connected to all the major cities of India by direct daily trains and weekly trains. Most of the railway network in Odisha lies under the jurisdiction of the East Coast Railway (ECoR) with headquarters at Bhubaneswar and some parts under South Eastern Railway and South East Central Railway.

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 10,302,917 | — |

| 1911 | 11,378,875 | +10.4% |

| 1921 | 11,158,586 | −1.9% |

| 1931 | 12,491,056 | +11.9% |

| 1941 | 13,767,988 | +10.2% |

| 1951 | 14,645,946 | +6.4% |

| 1961 | 17,548,846 | +19.8% |

| 1971 | 21,944,615 | +25.0% |

| 1981 | 26,370,271 | +20.2% |

| 1991 | 31,659,736 | +20.1% |

| 2001 | 36,804,660 | +16.3% |

| 2011 | 41,974,218 | +14.0% |

| Source: Census of India[125] | ||

Population

editAccording to the 2011 Census of India, Odisha accounted for approximately 3% of India's total population. The state had a population of 41,974,218, with 21,212,136 males (50.54%) and 20,762,082 females (49.46%), resulting in a sex ratio of 978 females per 1,000 males. This marked a growth rate of 13.97% during the 2001-2011 period, a decline from 16.25% in the previous decade (1991-2001). The population density stood at 269 people per square kilometer, with Ganjam district having the highest population among all districts in Odisha. In contrast, Debagarh district has the lowest population. The population in the age group of 0–6 years comprised 12% of the total population, with a child sex ratio of 934 females for every 1,000 males in this age group. Additionally, Scheduled Castes (SC) constituted a population of 7.2 million, making up 16.5% of the total population, while Scheduled Tribes (ST) accounted for 9.6 million, representing 22.1% of the population.[5]

Literacy and Socioeconomic Indicators

editAccording to the 2011 Census, Odisha's overall literacy rate is 72.87%. Male literacy stands at 81.59%, while female literacy is recorded at 64.01%. Odisha's literacy rate is slightly below the national average of 74.04%. Literacy rates vary within the state, with Khordha district having the highest literacy rate at 86.88%, while Nabarangpur has the lowest at 46.43%. In rural areas, the average literacy rate is 70.22%, compared to 85.57% in urban areas. Among the Scheduled Tribe population, the literacy rate is 52.24%.

In terms of poverty, Odisha had a poverty rate of 57.15% in 2004–2005, nearly double the national average of 26.10% at the time. However, since 2005, the state has made significant progress, reducing the poverty rate by 24.6 percentage points, with the current estimate at 32.6%.[126][127]

Health and Vital Statistics

editData from 1996–2001 indicated that the state’s life expectancy was 61.64 years, slightly above the national average. Odisha also records a birth rate of 23.2 per 1,000 people annually, a death rate of 9.1 per 1,000, an infant mortality rate of 65 per 1,000 live births.[128] In 2011-2013, Odisha recorded a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 222 per 100,000 live births, according to a report by NITI Aayog. As of 2018, Odisha’s Human Development Index (HDI) stands at 0.606.[128] The Total Fertility Rate (TFR) in Odisha declined from 2.1 in 2015-16 to 1.8 in 2020-21, paralleling the national trend, which saw a decrease from 2.2 to 2.0 during the same period.[129]

Religion

editBased on the 2011 Census, Odisha has a predominantly Hindu population, with 93.63% adhering to Hinduism. Christianity is the second-largest religion at 2.77%, followed by Islam at 2.17%. Smaller communities include Sikhs (0.05%), Jains (0.02%), and Buddhists (0.03%). Additionally, 1.14% of the population practices other religions, with Sarna being one of the prominent indigenous faiths,[131] particularly among tribal communities. A small segment, 0.18%, did not state their religious affiliation.[130]

Odisha is home to several Hindu figures. Sant Bhima Bhoi was a leader of the Mahima sect. Sarala Das, a Hindu Khandayat, was the translator of the epic Mahabharata into Odia. Chaitanya Das was a Buddhistic-Vaishnava and writer of the Nirguna Mahatmya. Jayadeva was the author of the Gita Govinda.

The Odisha Temple Authorisation Act of 1948 empowered the government of Odisha to open temples for all Hindus, including Dalits.[132]

Perhaps the oldest scripture of Odisha is the Madala Panji from the Puri Temple believed from 1042 AD. Famous Hindu Odia scripture includes the 16th-century Bhagabata of Jagannatha Dasa.[133] In the modern times Madhusudan Rao was a major Odia writer, who was a Brahmo Samajist and shaped modern Odia literature at the start of the 20th century.[134]

Decadal variations among religious communities

edit| Religion | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | |

| Hinduism | 14,368,411 | 98.11 | 17,123,194 | 97.57 | 21,121,056 | 96.25 | 25,161,725 | 95.42 | 29,971,257 | 94.67 | 34,726,129 | 94.35 | 39,300,341 | 93.63 |

| Islam | 176,338 | 1.20 | 215,319 | 1.23 | 326,507 | 1.49 | 422,266 | 1.60 | 577,775 | 1.82 | 761,985 | 2.07 | 911,670 | 2.17 |

| Christianity | 141,934 | 0.97 | 201,017 | 1.15 | 378,888 | 1.73 | 480,426 | 1.82 | 666,220 | 2.10 | 897,861 | 2.44 | 1,161,708 | 2.77 |

| Sikhism | 4,163 | 0.03 | 9,316 | 0.05 | 10,204 | 0.04 | 14,270 | 0.05 | 17,296 | 0.05 | 17,492 | 0.05 | 21,991 | 0.05 |

| Jainism | 1,248 | 0.01 | 6,521 | 0.03 | 6,642 | 0.03 | 6,302 | 0.02 | 9,154 | 0.02 | 9,420 | 0.02 | ||

| Buddhism | 969 | 0.01 | 8,462 | 0.04 | 8,028 | 0.03 | 9,153 | 0.03 | 9,863 | 0.03 | 13,852 | 0.03 | ||

| Other Religions and Persuasions | 2,883 | 0.02 | 91,859 | 0.42 | 273,596 | 1.04 | 397,798 | 1.26 | 361,981 | 0.98 | 478,317 | 1.14 | ||

| Not Stated | NA | NA | 1,118 | 0.01 | 3,318 | 0.01 | 13,935 | 0.04 | 20,195 | 0.05 | 76,919 | 0.18 | ||

| Total | 14,645,946 | 100 | 17,548,846 | 100 | 21,944,615 | 100 | 26,370,271 | 100 | 31,659,736 | 100 | 36,804,660 | 100 | 41,974,218 | 100 |

Languages

editOdia is the official language of Odisha[142] and is spoken by 82.70% of the population according to the 2011 census of India.[141] It is also one of the classical languages of India. English is the official language of correspondence between state and the union of India. Spoken Odia is not homogeneous as one can find different dialects spoken across the state. Some of the major dialects found inside the state are Sambalpuri, Cuttacki, Puri, Baleswari, Ganjami, Desiya, Kalahandia and Phulbani. The standard language is based on the Cuttacki dialect. In addition to Odia, significant populations of people speaking other major Indian languages like Hindi, Telugu, Urdu and Bengali are also found in the state, mainly in cities.[143]

The different tribal (Adivasi) communities who mostly reside in western and southern Odisha have their own languages belonging to Munda and Dravidian family of languages. Some of these major tribal languages are Santali, Kui, Mundari and Ho. Due to increasing contact with outsiders, migration and socioeconomic reasons many of these indigenous languages are slowly getting extinct or are on the verge of getting extinct.[144]

The Odisha Sahitya Academy Award was established in 1957 to actively develop Odia language and literature. The Odisha government launched a portal in 2018 to promote Odia language and literature.[145]

Education

editEntry to various institutes of higher education especially into engineering degrees is through a centralised Odisha Joint Entrance Examination, conducted by the Biju Patnaik University of Technology (BPUT), Rourkela, since 2003, where seats are provided according to order of merit.[146] Few of the engineering institutes enroll students by through Joint Entrance Examination. For medical courses, there is a corresponding National Eligibility Cum Entrance Test.

Culture

editCuisine

editOdisha has a culinary tradition spanning centuries. The kitchen of the Shri Jagannath Temple, Puri is reputed to be the largest in the world, with 1,000 chefs, working around 752 wood-burning clay hearths called chulas, to feed over 10,000 people each day.[147][148]

The syrupy dessert Pahala rasagola made in Odisha is known throughout the world.[149] Chhenapoda is another major Odisha sweet cuisine, which originated in Nayagarh.[150] Dalma (a mix of dal and selected vegetables) is widely known cuisine, better served with ghee.[citation needed]

The "Odisha Rasagola" was awarded a GI tag 29 July 2019 after a long battle about the origin of the famous sweet with West Bengal.[151]

Dance

editOdissi dance and music are classical art forms. Odissi is the oldest surviving dance form in India on the basis of archaeological evidence.[152] Odissi has a long, unbroken tradition of 2,000 years, and finds mention in the Natyashastra of Bharatamuni, possibly written c. 200 BC. However, the dance form nearly became extinct during the British period, only to be revived after India's independence by a few gurus.

The variety of dances includes Ghumura dance, Chhau dance, Jhumair, Mahari dance, Dalkhai, Dhemsa and Gotipua.

Sports

editThe state of Odisha has hosted several international sporting events, including the 2018 Men's Hockey World Cup, 2022 FIFA U-17 Women's World Cup and 2023 Men's Hockey World Cup.

Sports stadiums in Odisha include:

- Kalinga Stadium

- Barabati Stadium

- Jawaharlal Nehru Indoor Stadium

- East Coast Railway Stadium

- Biju Patnaik Hockey Stadium

- KIIT Stadium

- Veer Surendra Sai Stadium

- Birsa Munda International Hockey Stadium[153]

There are some High Performance Centres in the state as well which have been set up at Kalinga Stadium for the development of respective sports in Odisha. Some of the HPCs are as follows:

- Abhinav Bindra Targeting Performance (ABTP)

- Dalmia Bharat Gopichand Badminton Academy

- JSW Swimming HPC

- Khelo India State Centre of Excellence (KISCE) for Athletics, Hockey, and Weightlifting

- KJS Ahluwalia and Tenvic Sports HPC for Weightlifting

- Odisha Naval Tata Hockey High Performance Centre (ONTHHPC) [154]

- Odisha Aditya Birla and Gagan Narang Shooting HPC

- Reliance Foundation Odisha Athletics HPC

- SAI Regional Badminton Academy[155]

- Udaan Badminton Academy[156]

- AIFF High Performance Centre[157]

Tourism

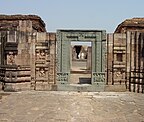

editThe Lingaraja Temple at Bhubaneswar has a 150-foot (46 m) high deula while the Jagannath Temple, Puri is about 200 feet (61 m) high and dominates the skyline. Only a portion of the Konark Sun Temple at Konark in Puri district, the largest of the temples of the "Holy Golden Triangle" exists today, and it is still staggering in size. It stands out as a masterpiece in Odisha architecture. Sarala Temple, regarded as one of the most spiritually elevated expressions of Shaktism is in Jagatsinghpur district. It is also one of the holiest places in Odisha and a major tourist attraction. Maa Tarini Temple situated in Kendujhar district is also a famous pilgrimage destination. Every day thousands of coconuts are given to Maa Tarini by devotees for fulfilling their wishes.[158]

Odisha's varying topography – from the wooded Eastern Ghats to the fertile river basin – has proven ideal for evolution of compact and unique ecosystems. This creates treasure troves of flora and fauna that are inviting to many migratory species of birds and reptiles. Bhitarkanika National Park in Kendrapada district is famous for its second largest mangrove ecosystem. The bird sanctuary in Chilika Lake (Asia's largest brackish water lake). The tiger reserve and waterfalls in Simlipal National Park, Mayurbhanj district are integral parts of eco-tourism in Odisha, arranged by Odisha Tourism.[159]

Daringbadi is a hill station in the Kandhamal district. It is known as "Kashmir of Odisha", for its climatic similarity. Chandipur, in Baleswar district is a calm and serene site, is mostly unexplored by tourists. The unique speciality of this beach is the ebb tides that recede up to 4 km and tend to disappear rhythmically.

In the western part of Odisha, Hirakud Dam in Sambalpur district is the longest earthen dam in the World. It also forms the biggest artificial lake in Asia. The Debrigarh Wildlife Sanctuary is situated near Hirakud Dam. Samaleswari Temple is a Hindu temple in Sambalpur city, dedicated to the goddess known as 'Samaleswari', the presiding deity of Sambalpur, is a strong religious force in western part of Odisha and Chhattisgarh state. The Leaning Temple of Huma is located near Sambalpur. The temple is dedicated to the Hindu god Lord Bimaleshwar. Sri Sri Harishankar Devasthana, is a temple on the slopes of Gandhamardhan hills, Balangir district. It is popular for its scenes of nature and connection to two Hindu lords, Vishnu and Shiva. On the opposite side of the Gandhamardhan hills is the temple of Sri Nrusinghanath, is situated at the foothills of Gandhamardhan Hill near Paikmal, Bargarh district.

In the southern part of Odisha, The Taratarini Temple on the Kumari hills at the bank of the Rushikulya River near Berhampur city in Ganjam district. Here worshiped as the Breast Shrine (Sthana Peetha) and manifestations of Adi Shakti. The Tara Tarini Shakti Peetha is one of the oldest pilgrimage centers of the Mother Goddess and is one of four major ancient Tantra Peetha and Shakti Peethas in India. Deomali is a mountain peak of the Eastern Ghats. It is located in Koraput district. This peak with an elevation of about 1,672 m, is the highest peak in Odisha.

The share of foreign tourists' arrival in the state is below one per cent of total foreign tourist arrivals at all India level.[160]

-

The Rath Yatra in Jagannath Temple, Puri

-

Gundichaghagi waterfall Keonjhar during monsoons

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Orissa Annual Reference 2005". Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "Odisha Review 2016" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Socio-economic Profile of Rural India (series II).: Eastern India (Orissa, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh). Centre for Rural Studies, L.B.S. National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie. 2011. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-8069-723-4. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Deomali Peak in Koraput India". www.india9.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Population, Size and Decadal Change" (PDF). Primary Census Abstract Data Highlights, Census of India. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 47th report (July 2008 to June 2010)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. pp. 122–126. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ "ODISHA Economic Survey Page 13" (PDF). ODISHA Economic Survey.

- ^ a b "Odisha Budget analysis". PRS India. 18 February 2020. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Standard: ISO 3166 — Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions". Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ "Vehicle registration number: OD to replace OR from today". Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Subnational HDI – Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "State of Literacy" (PDF). Census of India. p. 110. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Sex ratio of State and Union Territories of India as per National Health survey (2019–2021)". Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Blue Jay (PDF), Orissa Review, 2005, p. 87, archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2019, retrieved 7 October 2019

- ^ "Palapitta: How a mindless dasara ritual is killing our state bird palapitta – Hyderabad News". The Times of India. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Blue Jay (PDF), Orissa Review, 2005, archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2019, retrieved 7 October 2019

- ^ "State Fishes of India" (PDF). National Fisheries Development Board, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Pipal(Ficus religiosa) – The State Tree of Odisha (PDF), RPRC, 2014, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2020, retrieved 29 November 2020

- ^ "Odisha". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021.

- ^ "Odisha Name Alteration Act, 2011". eGazette of India. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "ST & SC Development, Minorities & Backward Classes Welfare Department:: Government of Odisha". stscodisha.gov.in. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "Coastal security". Odisha Police. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "The National Anthem of India" (PDF). Columbia University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Cabinet approved Odia as Classical Language". 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Detail History of Orissa". Government of Odisha. Archived from the original on 12 November 2006.

- ^ "Utkala Dibasa hails colours, flavours of Odisha". The Times of India. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Rabindra Nath Chakraborty (1985). National Integration in Historical Perspective: A Cultural Regeneration in Eastern India. Mittal Publications. pp. 17–. GGKEY:CNFHULBK119. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Ravi Kalia (1994). Bhubaneswar: From a Temple Town to a Capital City. SIU Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8093-1876-6. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database". Global Data Lab. Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Patel, C.B (April 2010). Origin and Evolution of the Name ODISA (PDF). Bhubaneswar: I&PR Department, Government of Odisha. pp. 28, 29, 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Pritish Acharya (11 March 2008). National Movement and Politics in Orissa, 1920–1929. SAGE Publications. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-321-0001-0. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ "Amid clash, House passes Bills to rename Orissa, its language". The Hindu. 9 November 2010. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Parliament passes bill to change Orissa's name". NDTV. 24 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Orissa wants to change its name to Odisha". Rediff.com. 10 June 2008. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Amalananda Ghosh (1990). An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. BRILL. p. 24. ISBN 9004092641. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ Subodh Kapoor, ed. (2004). An Introduction to Epic Philosophy: Epic Period, History, Literature, Pantheon, Philosophy, Traditions, and Mythology, Volume 3. Genesis Publishing. p. 784. ISBN 9788177558814. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

Finally Srutayudha, a valiant hero, was son Varuna and of the river Parnasa.

- ^ Devendrakumar Rajaram Patil (1946). Cultural History from the Vāyu Purāna. Motilal Banarsidass Pub. p. 46. ISBN 9788120820852. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Sudama Misra (1973). Janapada state in ancient India. Bhāratīya Vidyā Prakāśana. p. 78.

- ^ "Dance bow (1965.3.5)". Pitt Rivers Museum. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Rabindra Nath Pati (1 January 2008). Family Planning. APH Publishing. p. 97. ISBN 978-81-313-0352-8. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Suhas Chatterjee (1 January 1998). Indian Civilization And Culture. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 68. ISBN 978-81-7533-083-2. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ a b Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 9780415329194. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ a b Mookerji Radhakumud (1995). Asoka. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 214. ISBN 978-81-208-0582-8. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen (1 January 1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 153. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ Austin Patrick Olivelle Alma Cowden Madden Centennial Professor in Liberal Arts University of Texas (19 June 2006). Between the Empires : Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Reddy (1 December 2006). Indian Hist (Opt). Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. A254. ISBN 978-0-07-063577-7. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Indian History. Allied Publishers. 1988. p. 74. ISBN 978-81-8424-568-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Ronald M. Davidson (13 August 2013). Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement. Columbia University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-231-50102-6. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ R. C. Majumdar (1996). Outline of the History of Kalinga. Asian Educational Services. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-206-1194-8. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Roshen Dalal (18 April 2014). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books Limited. p. 559. ISBN 978-81-8475-396-7. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. 1960. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-07-132923-1. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

- ^ Orissa General Knowledge. Bright Publications. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-7199-574-5. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ L.S.S. O'Malley (1 January 2007). Bengal District Gazetteer : Puri. Concept Publishing Company. p. 33. ISBN 978-81-7268-138-8. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan India. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-230-32885-3. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Devi, Bandita (January 1992). Some Aspects of British Administration in Orissa, 1912–1936. Academic Foundation. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7188-072-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ William A. Dando (13 February 2012). Food and Famine in the 21st Century [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-59884-731-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ J. K. Samal; Pradip Kumar Nayak (1 January 1996). Makers of Modern Orissa: Contributions of Some Leading Personalities of Orissa in the 2nd Half of the 19th Century. Abhinav Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-81-7017-322-9. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ K.S. Padhy (30 July 2011). Indian Political Thought. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 287. ISBN 978-81-203-4305-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Usha Jha (1 January 2003). Land, Labour, and Power: Agrarian Crisis and the State in Bihar (1937–52). Aakar Books. p. 246. ISBN 978-81-87879-07-7. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ a b Bandita Devi (1 January 1992). Some Aspects of British Administration in Orissa, 1912–1936. Academic Foundation. p. 214. ISBN 978-81-7188-072-0. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ "Hubback's memoirs: First Governor Of State Reserved Tone Of Mild Contempt For Indians". The Telegraph. 29 November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ B. Krishna (2007). India's Bismarck, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Indus Source. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-81-88569-14-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ "Merger of the Princely States of Odisha – History of Odisha". 5 April 2018. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Geography of Odisha". Know India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ "Cuttack". Government of Odisha. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ Dasgupta, Alakananda; Priyadarshini, Subhra (29 May 2019). "Why Odisha is a sitting duck for extreme cyclones". Nature India. doi:10.1038/nindia.2019.69 (inactive 1 November 2024). Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Socio-economic Profile of Rural India (series II).: Eastern India (Orissa, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh). Concept Publishing Company. 2011. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-8069-723-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Monthly mean maximum & minimum temperature and total rainfall based upon 1901–2000 data" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ "Study shows Odisha forest cover shrinking". The Times of India. 16 February 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ Underutilized and Underexploited Horticultural Crops. New India Publishing. 1 January 2007. p. 116. ISBN 978-81-89422-60-8. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Orchid House a haven for nature lovers". The Telegraph. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Similipal Tiger Reserve". World Wide Fund for Nature, India. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Banished from their homes". The Pioneer. 29 August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Away from home, Chandaka elephants face a wipeout". The New Indian Express. 23 August 2013. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ Sharad Singh Negi (1 January 1993). Biodiversity and Its Conservation in India. Indus Publishing. p. 242. ISBN 978-81-85182-88-9. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ Venkatesh Salagrama (2006). Trends in Poverty and Livelihoods in Coastal Fishing Communities of Orissa State, India. Food & Agriculture Org. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-92-5-105566-3. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Coast Guard launches 'Operation Oliver'". The Hindu. 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Olive Ridley turtles begin mass nesting". The Hindu. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Mass nesting of Olive Ridleys begins at Rushikulya beach". The Hindu. 15 March 2004. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Observations (iNaturalist) Bhitarkanika". www.iNaturalist.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Bhitarkanika Park to be Closed for Crocodile Census". The New Indian Express. 3 December 2013. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Bird Count Rises in Bhitarkanika". The New Indian Express. 14 September 2014. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Concern over dwindling horseshoe crab population". The Hindu. 8 December 2013. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ Pushpendra K. Agarwal; Vijay P. Singh (16 May 2007). Hydrology and Water Resources of India. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 984. ISBN 978-1-4020-5180-7. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Number of birds visiting Chilika falls but new species found". The Hindu. 9 January 2013. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Chilika registers sharp drop in winged visitors". The Hindu. 13 January 2014. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Two new species of migratory birds sighted in Chilika Lake". The Hindu. 8 January 2013. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Dolphin population on rise in Chilika Lake". The Hindu. 18 February 2010. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Maiden Dolphin Census in State's Multiple Places on Cards". The New Indian Express. 20 January 2015. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ Rongmei, Precious. "Empty beaches, dolphins and more at Odisha's Rajhans Island". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Wildlife Census – Odisha Wildlife Organisation". Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ P.K. Dash; Santilata Sahoo; Subhasisa Bal (2008). "Ethnobotanical Studies on Orchids of Niyamgiri Hill Ranges, Orissa, India". Ethnobotanical Leaflets (12): 70–78. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ Chandan Sengupta; Stuart Corbridge (28 October 2013). Democracy, Development and Decentralisation in India: Continuing Debates. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-136-19848-9. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Our Parliament" (PDF). Lok Sabha. Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ a b "BJD's landslide victory in Odisha, wins 20 of 21 Lok Sabha seats". CNN-IBN. 17 May 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ https://www.livemint.com/politics/odisha-gets-a-news-cm-after-24-years-who-is-mohan-charan-majhi-5-points-11718111115393.html [bare URL]

- ^ Ada W. Finifter. Political Science. FK Publications. p. 94. ISBN 978-81-89597-13-9. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b Rajesh Kumar (17 January 2024). Universal's Guide to the Constitution of India. Universal Law Publishing. pp. 107–110. ISBN 978-93-5035-011-9. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Ramesh Kumar Arora; Rajni Goyal (1995). Indian Public Administration: Institutions and Issues. New Age International. pp. 205–207. ISBN 978-81-7328-068-9. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Subhash Shukla (2008). Issues in Indian Polity. Anamika Pub. & distributors. p. 99. ISBN 978-81-7975-217-3. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ a b "About Department". Revenue & Disaster Management Department, Government of Odisha. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ Laxmikanth. Governance in India. McGraw-Hill Education (India) Pvt Limited. pp. 6–17. ISBN 978-0-07-107466-7. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Administrative Unit". Revenue & Disaster Management Department, Government of Odisha. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ Siuli Sarkar (9 November 2009). Public Administration in India. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 117. ISBN 978-81-203-3979-8. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Public Administration Dictionary. Tata McGraw Hill Education. 2012. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-259-00382-0. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ "GDP growth: Most states grew faster than national rate in 2012–13". The Financial Express. 12 December 2013. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Bhubaneswar leads Govt's Smart City list, Rs 50,802 crore to be invested over five years". The Indian Express. 29 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ "Indian states that attracted highest FDI". Rediff. 29 August 2012. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ "Rourkela Steel Plant". Sail.co.in. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Nippon Steel Corporation to set up 30 MTPA plant in Odisha". The New Indian Express. 5 April 2023. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Reliance to invest Rs 60,000-cr for Orissa power plant". dna. 21 July 2006. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Gujarat, Odisha and Andhra top 3 Domestic Investment Destinations of 2009". Assocham. 21 January 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ "NH 42". Odishalinks.com. 16 June 2004. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ "Odisha plans metro, signs contract for detailed project report preparation". The Times of India. 23 August 2014. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "Puri-Bhubaneswar Mega Metro Rail Project Soon?". 8 February 2023. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Odisha Approves Metro Train Project Between Cuttack, Bhubaneswar and Puri". Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ "Odisha plans new Expressway between Bhubaneswar & Puri – the New Indian Express". Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Ten-year roadmap for State's civil aviation". The Pioneer. India. 4 August 2012. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

at present there are 17 airstrips and 16 helipads in Odisha

- ^ "10-year roadmap set up to boost Odisha civil aviation". Odisha Now.in. 2012. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

Odisha has 17 airstrips and 16 helipads.

- ^ "Odisha initiate steps for intra and inter state aviation facilities". news.webindia123.com. 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

Odisha has 17 airstrips and 16 helipads

- ^ Sujit Kumar Bisoyi (13 November 2018). "Adani Group plans airport at Dhamra". Times of India. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Division, P. India 2019: A Reference Annual. Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. p. 701. ISBN 978-81-230-3026-5. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ India. Parliament. Rajya Sabha (2012). Parliamentary Debates: Official Report. Council of States Secretariat. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ "Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "India States Briefs – Odisha". World Bank. 31 May 2016. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ "NITI Aayog report: Odisha tops in poverty reduction rate among other states". Pragativadi: Leading Odia Dailly. 30 July 2017. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Sub-national HDI – Subnational HDI – Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "NFHS-5, Phase-2" (PDF). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Table C-01 Population by Religious Community: Odisha". Census of India, 2011. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ "C-01 Appendix: Details of religious community shown under 'Other religions and persuasions' in main table C01 - 2011" (XLS). Census of India. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ P. 63 Case studies on human rights and fundamental freedoms: a world survey, Volume 4 By Willem Adriaan Veenhoven

- ^ P. 77 Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 30 By Scholastic Library Publishing

- ^ Madhusudan Rao By Jatindra Mohan Mohanty, Sahitya Akademi

- ^ "C-01: Population by religious community (2011)". Census India. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "C-01: Population by religious community (2001)". Census India. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "C-9 Religion (1991)". Census India. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Portrait of Population - Census 1981" (PDF). Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ "Census Atlas, Vol-XII-Part IX-A, Orissa - Census 1961" (PDF). Census India. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "General Population, Social and Cultural and Land Tables, Part II-A, Tables, Volume-XI, Orissa - Census 1951" (PDF). Census India. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Table C-16 Population by Mother Tongue: Odisha". Census of India 2011. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ ":: Law Department (Government of Odisha) ::". lawodisha.gov.in. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Mahapatra, B. P. (2002). Linguistic Survey of India: Orissa (PDF). Kolkata, India: Language Division, Office of the Registrar General. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "Atlas of languages in danger | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ "Odia vartual academy". Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Biju Patnaik University of Technology". Bput.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ National Association on Indian Affairs; American Association on Indian Affairs (1949). Indian Affairs. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ S.P. Sharma; Seema Gupta (3 October 2006). Fairs & Festivals of India. Pustak Mahal. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-81-223-0951-5. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Mitra Bishwabijoy (6 July 2015). "Who invented the rasgulla?". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ "Chhenapoda". Simply TADKA. 15 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Odisha Rasagola receives geographical indication tag; here's what it means". www.businesstoday.in. 29 July 2019. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Odissi Kala Kendra". odissi.itgo.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ Suffian, Mohammad (16 February 2021). "Odisha CM Lays Foundation of India's Largest Hockey Stadium named after 'Birsa Munda' In Rourkela". India Today. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Naval Tata Hockey Academy Inaugurated In Odisha Capital". Kalinga TV. 13 August 2019. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Minati Singha (15 May 2017). "Odisha-SAI Regional Badminton Academy inaugurated in Bhubaneswar". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Udaan Badminton Academy-HOME". www.theudaan.net. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "High Performance Centre deal a big boost for Odisha and AIFF | Goal.com". www.goal.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Norenzayan, Ara (25 August 2013). Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict. Princeton University Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-4008-4832-4. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ "MTN 82:9–10 Olive ridley tagged in Odisha recovered in the coastal waters of eastern Sri Lanka". Seaturtle.org. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ "Odisha – Economic Survey 2014–15" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

External links

edit- Government

- General information

- Odisha web resources provided by GovPubs at the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- Odisha at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Wikimedia Atlas of Odisha

- Geographic data related to Odisha at OpenStreetMap