Nez Perce, also spelled Nez Percé or called nimipuutímt (alternatively spelled nimiipuutímt, niimiipuutímt, or niimi'ipuutímt), is a Sahaptian language related to the several dialects of Sahaptin (note the spellings -ian vs. -in). Nez Perce comes from the French phrase nez percé, "pierced nose"; however, Nez Perce, who call themselves nimíipuu, meaning "the people", did not pierce their noses.[3] This misnomer may have occurred as a result of confusion on the part of the French, as it was surrounding tribes who did so.[3]

| Nez Perce | |

|---|---|

| niimiipuutímt | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Idaho |

| Ethnicity | 610 Nez Perce people (2000 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 20 (2007)[2] |

Penutian?

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | nez |

| Glottolog | nezp1238 |

| ELP | Nez Perce |

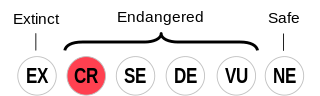

Nez Perce is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

The Sahaptian sub-family is one of the branches of the Plateau Penutian family (which, in turn, may be related to a larger Penutian grouping). It is spoken by the Nez Perce people of the Northwestern United States.

Nez Perce is a highly endangered language. While sources differ on the exact number of fluent speakers, it is almost definitely under 100. The Nez Perce tribe is endeavoring to reintroduce the language into native usage through a language revitalization program, but (as of 2015) the future of the Nez Perce language is far from assured.[4]

Phonology

editThe phonology of Nez Perce includes vowel harmony (which was mentioned in Noam Chomsky & Morris Halle's The Sound Pattern of English), as well as a complex stress system described by Crook (1999).[5]

Consonants

edit| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | sibilant | lateral | plain | lab. | plain | lab. | |||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

plain | p | t | ts | k | (kʷ) | q | (qʷ) | ʔ | ||

| ejective | pʼ | tʼ | tsʼ | tɬʼ | kʼ | (kʼʷ) | qʼ | (qʼʷ) | |||

| Fricative | s | ɬ | ( ʃ ) | x | χ | h | |||||

| Sonorant | plain | m | n | l | j | w | |||||

| glottalized | mʼ | nʼ | lʼ | jʼ | wʼ | ||||||

The sounds kʷ, kʼʷ, qʷ, qʼʷ and ʃ only occur in the Downriver dialect.[6]

Vowels

editNez Perce has an average-sized inventory of five vowels, each marked for length. Unusually for a five-vowel system, however, it lacks a mid front vowel /e/, with low front /æ/ in its place. Such an asymmetrical configuration is found in less than five percent of the languages that distinguish exactly five vowels, and among those that do display an asymmetry, the "missing" vowel is overwhelmingly more likely to be a back vowel /u/ or /o/ than front /e/. Indeed, Nez Perce's lack of a mid front vowel within a five-vowel system appears unique, and contrary to basic tendencies toward triangularity in the allocation of vowel space. A potential reason for this peculiarity is discussed in the section on vowel harmony below.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | o oː | ||

| Low | æ æː ⟨e ee⟩ | a aː |

Stress is marked with an acute accent ⟨á, é, í, ó, ú⟩.

Diphthongs

editNez Perce distinguishes seven diphthongs, all with phonemic length:

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (level) | iu̯ iːu̯ | ui̯ uːi̯ | |

| Mid (rising) | oi̯ oːi̯ | ||

| Low (rising) | æu̯ æːu̯ æi̯ æːi̯ | au̯ aːu̯ ai̯ aːi̯ |

Vowel harmony

editNez Perce displays an extensive system of vowel harmony. Vowel qualities are divided into two opposing sets, "dominant" /i a o/ and "recessive" /i æ u/. The presence of a dominant vowel causes all recessive vowels within the same phonological word to assimilate to their dominant counterpart; hence with the addition of the dominant-marked suffix /-ʔajn/:

With very few exceptions, therefore, phonological words may contain only vowels of the dominant or recessive set. Despite occurring in both sets, /i/ is not neutral; instead, it is either dominant or recessive depending on the morpheme in which it occurs.

This system presents a challenge to common concepts of vowel harmony, since it does not appear to be based on obvious considerations of backness, height, or tongue root position. To account for this, Katherine Nelson (2013)[8] proposes that the two sets be considered as distinct "triangles" of vowel space, each by themselves maximally dispersed, where the recessive set is somewhat retracted (further back) in comparison to the dominant:

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i (→ i) | u → o | |

| Low | æ → a | ||

This dual system would simultaneously explain two apparent phonological aberrances: the absence of a mid front vowel /e/, and the fact that phonemic /i/ can be marked either as dominant or recessive. Since the three vowels of a given set are placed with regard to the other vowels of the same set, the low height of the front vowel /æ/ appears natural (that is, maximally dispersed) against its high counterparts /i u/, as in a three-vowel system such as those of Arabic and Quechua. The high front vowel /i/ meanwhile, is retracted much less in the transition from recessive to dominant - little enough that the distinction does not surface phonemically - and therefore can be placed near to the crux around which the triangle of vowel space is "tilted" by retraction.[8]

Syllable structure

editThe Nez Perce syllable canon is CV(ː)(C)(C)(C)(C); that is, a mandatory consonant-vowel sequence with optional vowel length, followed by up to four coda consonants. The arrangement of permitted coda clusters is summarized in the following table, where segments in each column can follow those to their right (C' represents any glottalized consonant), except when the same consonant would occur twice:

| C1 | V(ː) | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Any consonant) | (Any vowel) | NOT (k, q, h, C') | téhes "ice" | |||

| NOT (ɬ, C') | NOT (k, q, h, C') | só·ts "deep water" | ||||

| NOT (p, t, k, q, C') | p, t, c, q, x, y | t, c, s, x | lílps "mushroom sp." | |||

| p, ʔ, h, x | t, c, n, y, w, s | p, k, s, x, q | t, c, s | t̓úxsks "I smashed with hand" | ||

Writing system

edit| a | a· | c | c’ | e | é· | h | i | í· | k | k’ | l | l’ | ł | ƛ | m | m’ | n | n’ | o |

| ó· | p | p’ | q | q’ | s | t | t’ | u | ú· | w | w’ | x | x̂ | y | y’ | ʔ |

Grammar

editAs in many other indigenous languages of the Americas, a Nez Perce verb can have the meaning of an entire sentence in English. This manner of providing a great deal of information in one word is called polysynthesis. Verbal affixes provide information about the person and number of the subject and object, as well as tense and aspect (e.g. whether or not an action has been completed).

ʔew

1/2-3.OBJ

ʔilíw

fire

wee

fly

ʔinipí

grab

qaw

straight.through

tée

go.away

ce

IMPERF.PRES.SG

'I go to scoop him up in the fire'[10]

Documentation History

editAsa Bowen Smith developed the Nez Perce grammar by adapting the missionary alphabet used in Hawaiian missions, and adding the consonants s and t.[12] In 1840, Asa Bowen Smith wrote the manuscript for the book Grammar of the Language of the Nez Perces Indians Formerly of Oregon, U.S..[13] The grammar of Nez Perce has been described in a grammar (Aoki 1973) and a dictionary (Aoki 1994) with two dissertations.[14][5]

Case

editNez Perce nouns are marked for grammatical case. Nez Perce employs a three-way case-marking strategy: a transitive subject, a transitive object, and an intransitive subject are each marked differently. It is thus an example of the very rare type of tripartite languages (see morphosyntactic alignment).

Nouns in Nez Perce are marked based on how they relate to the transitivity of the verb. Subjects in a sentence with a transitive verb take the ergative suffix -nim, objects in a sentence with a transitive verb take the accusative suffix -ne, and subjects in sentences with an intransitive verb don’t take a suffix.

| Ergative | Accusative | Intransitive subject |

|---|---|---|

| suffix -nim | suffix -ne (here subject to vowel harmony, resulting in surface form -na) |

|

ᶍáᶍaas-nim grizzly-ERG hitwekǘxce he.is.chasing ‘Grizzly is chasing me’ |

ʔóykalo-m all-ERG titóoqan-m people-ERG páaqaʔancix they.respect.him ᶍáᶍaas-na grizzly-ACC ‘All people respect Grizzly’ |

Verbal morphology

editThe Nez perce verb encodes number (and to a lesser extent person) for one or two arguments, and also has a very rich system suffixal system encoding tense, aspect, polarity and associated motion. In addition, it has a series of hundreds of preverbs encoding intrument, posture and various unusual categories.

In particular, it has one of the richest system of periodic tense among the world's languages, including matutinal, diurnal, vesperal, nocturnal and hivernal,[16] as illustrated in the following examples (examples from Aoki 1994: 751–752, interlinear glosses from Jacques 2023:2-3).

méy-tip-se

MAT-eat.meal-PRS:SG

‘I am having breakfast.’

halx̣pa-típ-sa

DIU-eat.meal-PRS:SG

‘I am eating lunch.’

kulewí·-tip-se

VESP-eat.meal-PRS:SG

‘I am eating supper.’

te·w-c͗íq-ce

NOCT-talk-PRS:SG

‘I am talking at night.

ʔelíw-tin̉k-ce

HIB-die-PRS:SG

‘I am starving in winter.’

The Nez perce verb has three different ways of expressing simulative 'pretend': a suffix -tay, the combination of the reflexive indexation prefix with the 'by mouth' instrumental preverb, and the simulative -né·wi suffix.[17]

hip-táy-ca

eat-SIMUL-PRS:SG

‘I am pretending to eat.’

ʔin-ú·-tin’k-se

REFL:1SG-by.mouth-die-PRS:SG

‘I pretend to be dead.’

ʔipn-u·-wepcux-né·wi-se

REFL:3SG-by.mouth-smart-SIMUL-PRS:SG

‘He pretends to be smart.’ (Aoki 1994:479–480)

Word order

editThe word order in Nez Perce is quite flexible and serves to introduce information on the topic and focus of a sentence.

Verb–subject–object word order

kii

this

pée-ten’we-m-e

3→3-talk-CSL-PAST

qíiw-ne

old.man-OBJ

’iceyéeye-nm

coyote-ERG

‘Now the coyote talked to the old man’

Subject–verb–object word order

Kaa

and

háatya-nm

wind-ERG

páa-’nahna-m-a

3→3-carry-CSL-PAST

’iceyéeye-ne

coyote-OBJ

‘And the wind carried coyote here’

Subject–object–verb word order

Kawó’

then

kii

this

háama-pim

husband-ERG

’áayato-na

woman-OBJ

pée-’nehnen-e

3→3-take.away-PAST

‘Now then the husband took the woman away’[18]

References

edit- ^ Nez Perce language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- ^ a b "Facts for Kids: Nez Perce Indians (Nez Perces)". www.bigorrin.org. Retrieved 2017-02-09.

- ^ "Nimi'ipuu Language Teaching and Family Learning". NILI Projects. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

- ^ a b Crook 1999.

- ^ a b c Aoki 1994.

- ^ Aoki 1966.

- ^ a b Nelson 2013.

- ^ "Phonetic Alphabet". Colville Tribes Language Program.

- ^ Cash Cash 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Aoki 1979.

- ^ "Nez Perce National Historical Park". National Park Service. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- ^ Smith & Tingley 1840.

- ^ Rude 1985.

- ^ Mithun 1999.

- ^ Jacques, Guillaume (2023). "Periodic tense markers in the world's languages and their sources". Folia Linguistica. 57 (3): 539–562. doi:10.1515/flin-2023-2013.

- ^ Jacques, Guillaume (2023). "Simulative derivations in cross-linguistic perspective and their diachronic sources". Studies in Language. 47 (4): 957–988. doi:10.1075/sl.22054.jac.

- ^ Rude 1992.

Bibliography

edit- Aoki, Haruo (1994). Nez Perce Dictionary. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-09763-6.

- Aoki, Haruo (1973). Nez Perce Grammar. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02524-0.

- Aoki, Haruo (1979). Nez Perce Texts. University of California publications in linguistics. Vol. 90. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09593-6. 2, 3

- Aoki, Haruo; & Whitman, Carmen. (1989). Titwáatit: (Nez Perce Stories). Anchorage: National Bilingual Materials Development Center, University of Alaska. ISBN 0-520-09593-6. (Material originally published in Aoki 1979).

- Aoki, Haruo; & Walker, Deward E., Jr. (1989). Nez Perce oral narratives. University of California publications in linguistics (Vol. 104). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09593-6.

- Cash Cash, Phillip (2004). "Nez Perce verb morphology" (PDF). Unpublished manuscript. Tucson: University of Arizona. Archived from the original (PDF) on Nov 3, 2020.

- Crook, Harold D. (1999). The phonology and morphology of Nez Perce stress (Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Los Angeles.

- Mithun, Marianne (1999). The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7.

- Rude, Noel E. (1985). Studies in Nez Perce grammar and discourse (Doctoral dissertation). University of Oregon.

- Rude, Noel E. (1992). "Word Order and Topicality in Nez Perce". Pragmatics of Word Order Flexibility. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 193–208. doi:10.1075/tsl.22.08rud.

- Nelson, Katherine (June 2013). "The Nez Perce vowel system: A phonetic analysis". Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics. 19. doi:10.1121/1.4800241.

- Smith, Asa Bowen; Tingley, Sylvanus (1840). Grammar of the Language of the Nez Perces Indians Formerly of Oregon, U.S.: From the manuscript of Rev. A.B. Smith dated Sept. 28, 1840. Now in archives of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Boston, Mass. Volume 138. OCLC 39088111. Retrieved 2021-11-04 – via WorldCat.

Vowel harmony

edit- Aoki, Haruo (December 1966). "Nez Perce Vowel Harmony and Proto-Sahaptian Vowels". Language. 42 (4): 759–767. doi:10.2307/411831. JSTOR 411831.

- Aoki, Haruo (1968). "Toward a typology of vowel harmony". International Journal of American Linguistics. 34 (2): 142–145. doi:10.1086/465006. S2CID 143700904.

- Chomsky, Noam; & Halle, Morris. (1968). Sound pattern of English (pp. 377–378). Studies in language. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hall, Beatrice L.; & Hall, R. M. R. (1980). Nez Perce vowel harmony: An Africanist explanation and some theoretical consequences. In R. M. Vago (Ed.), Issues in vowel harmony (pp. 201–236). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Jacobsen, William (1968). "On the prehistory of Nez Perce vowel harmony". Language. 44 (4): 819–829. doi:10.2307/411901. JSTOR 411901.

- Kim, Chin (1978). 'Diagonal' vowel harmony?: Some implications for historical phonology. In J. Fisiak (Ed.), Recent developments in historical phonology (pp. 221–236). The Hague: Mouton.

- Lightner, Theodore (1965). "On the description of vowel and consonant harmony". Word. 21 (2): 244–250. doi:10.1080/00437956.1965.11435427.

- Rigsby, Bruce (1965). "Continuity and change in Sahaptian vowel systems". International Journal of American Linguistics. 31 (4): 306–311. doi:10.1086/464860. S2CID 144876511.

- Rigsby, Bruce; Silverstein, Michael (1969). "Nez Perce vowels and proto-Sahaptian vowel harmony". Language. 45 (1): 45–59. doi:10.2307/411752. JSTOR 411752.

- Zimmer, Karl (1967). "A note on vowel harmony". International Journal of American Linguistics. 33 (2): 166–171. doi:10.1086/464954. S2CID 144825775.

- Zwicky, Arnold (1971). "More on Nez Perce: On alternative analyses". International Journal of American Linguistics. 37 (2): 122–126. doi:10.1086/465146. hdl:1811/85957. S2CID 96455877.

Language learning materials

editDictionaries and vocabulary

edit- Aoki, Haruo. (1994). Nez Perce dictionary. University of California publications in linguistics (Vol. 112). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09763-7.

- "Nez Perce Literature and vocabulary". Indigenous Peoples' Literature. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- McBeth, Sue. "Nez Perce-English Dictionary samples". Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Nez Perce-English Vocabulary" (PDF). Nez Perce National Historical Park. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Morvillo, Anthony (1895). A Dictionary of the Numípu Or Nez Perce Language. St. Ignatius' Mission Print, Montana. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Nez Perce Language and the Nez Perce Indian Tribe (Nimipu, Nee-me-poo, Chopunnish, Sahaptin)". native-languages.org. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

Grammar

edit- Aoki, Haruo. (1965). Nez Perce grammar. University of California, Berkeley.

- Aoki, Haruo. (1970). Nez Perce grammar. University of California publications in linguistics (Vol. 62). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09259-7. (Reprinted 1973, California Library Reprint series).

- Missionary in the Society of Jesus in the Rocky Mountains (1891). A Numipu or Nez-Perce grammar. Desmet, Idaho: Indian Boys' Press. ISBN 9780665175299. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

Texts and courses

edit- "Nimipuutimt Calendar and Nez Perce Tribe Language Program". Archived from the original on 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Aoki, Haruo. (1979). Nez Perce texts. University of California publications in linguistics (Vol. 90). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09593-6., 2, 3

- Aoki, Haruo; & Whitman, Carmen. (1989). Titwáatit: (Nez Perce Stories). Anchorage: National Bilingual Materials Development Center, University of Alaska. ISBN 0-520-09593-6. (Material originally published in Aoki 1979).

- "Nez Perce Language Courses" (Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures and American Indian Studies Program, University of Idaho). Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Rockliff, J. A. (1915). "The Life of Jesus Christ from the Four Gospels in the Nez Perce Language". Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Nez Perce language - Audio Bible stories and lessons". Global Recordings Network. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Nez Perce Language Courses" (Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures and American Indian Studies Program, University of Idaho). Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Nez Perce Literature and vocabulary". Indigenous Peoples' Literature. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Watters, Mari. (1990). Nez Perce tapes and texts. [5 audio cassettes & 1 booklet]. Moscow, Idaho: Mari Watters Productions, Upward Bound, College of Education, University of Idaho.

External links

edit- "Haruo Aoki Papers on the Nez Perce Language". California Language Archive. Retrieved 2013-09-22.

- Nez Perce language videos, YouTube

- Phillip Cash Cash website (Nez Perce researcher)

- Nez Perce sounds

- Joseph Red Thunder: Speech of August 6, 1989 at the Big Hole National Battlefield Commemorating our Nez Perce Ancestors (has audio)

- Hinmatóowyalahtq'it: Speech of 1877 as retold by Jonah Hayes (ca. 1907)[permanent dead link] (.mov)

- Fox narrative animation (.swf)

- Nez Perce Verb Morphology (.pdf)

- wéeyekweʔnipse ‘to sing one’s spirit song’: Performance and metaphor in Nez Perce spirit-singing (.pdf)

- Tɨmnákni Tímat (Writing from the Heart): Sahaptin Discourse and Text in the Speaker Writing of X̣ílux̣in (.pdf)

- A map of American languages (TITUS project)

- Nez Percé at the Rosetta Project

- OLAC resources in and about the Nez Perce language