Neuchâtel (UK: /ˌnɜːʃæˈtɛl/, US: /-ʃɑːˈ-, ˌnjuːʃəˈ-, ˌnʊʃɑːˈ-/;[3][4][5] French: [nøʃɑtɛl] ⓘ; German: Neuenburg [ˈnɔʏənbʊrɡ] ⓘ) is a town, a municipality, and the capital of the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel on Lake Neuchâtel. Since the fusion in 2021 of the municipalities of Neuchâtel, Corcelles-Cormondrèche, Peseux, and Valangin,[6] the city has approximately 33,000 inhabitants (80,000 in the metropolitan area).[7][8] The city is sometimes referred to historically by the German name Neuenburg; both the French and German names mean "New Castle".

Neuchâtel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 47°0′N 6°56′E / 47.000°N 6.933°E | |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Canton | Neuchâtel |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Conseil communal with 5 members |

| • Mayor | Le Président du Conseil communal (list) Fabio Bongiovanni FDP/PRD/PLR (as of January 2017) |

| • Parliament | Conseil général with 41 members |

| Area | |

• Total | 18.05 km2 (6.97 sq mi) |

| Elevation (railway station) | 479 m (1,572 ft) |

| Highest elevation (Grand Chaumont) | 1,177 m (3,862 ft) |

| Lowest elevation (Port) | 434 m (1,424 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2018)[2] | |

• Total | 33,475 |

| • Density | 1,900/km2 (4,800/sq mi) |

| Demonym | French: Neuchâtelois(e) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (Central European Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (Central European Summer Time) |

| Postal code(s) | 2000 |

| SFOS number | 6458 |

| ISO 3166 code | CH-NE |

| Localities | La Coudre, Serrières, Pierre-à-Bot, Gorges du Seyon, Chaumont, Petit Chaumont, Grand Chaumont, Peseux, Corcelles-Cormondrèche, Valangin |

| Surrounded by | Auvernier, Boudry, Chabrey (VD), Colombier, Cressier, Cudrefin (VD), Delley-Portalban (FR), Enges, Fenin-Vilars-Saules, Hauterive, Saint-Blaise, Savagnier |

| Twin towns | Aarau (Switzerland), Besançon (France), Sansepolcro (Italy) |

| Website | neuchatelville SFSO statistics |

The castle after which the city is named was built by Rudolph III of Burgundy and completed in 1011. Originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy, the city was absorbed into the Holy Roman Empire in 1033. The domain of the counts of Neuchatel was first referred to as a city in 1214. The city came under Prussian control from 1707 until 1848, with an interruption during the Napoleonic Wars from 1806 to 1814. In 1848, Neuchâtel became a republic and a canton of Switzerland.

Neuchâtel is a centre of the Swiss watch industry, the site of micro-technology and high-tech industries, and home to research centres and organizations such as the Swiss Center for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM), and Philip Morris International's Cube.

Names and etymology

editNeuchâtel is a medieval toponym derived from the Old French: neu "new" (Modern French neuf) and châtel "castle" (now château) in reference to the 10th century Neuchâtel Castle.[a] In French, most adjectives, when used attributively, appear after their nouns; however, the leading position of the adjective is a phenomenon widely attested in the north and east of France, as well as in Belgium and in French-speaking Switzerland (Romandy). As with the various other places named Neuchâtel, Neufchâtel, Neufchâteau of northern France and Belgium, this reflects the Germanic influence on Gallo-Romance languages retained in the toponymy today.[11][12] This contrasts with the Occitan Castelnaus (and the Frenchified Châteauneufs) in the south of France.

The German name for the town is Neuenburg, which also translates roughly as "new castle". The longer form Neuenburg am See ("Newcastle by the lake") is sometimes used to disambiguate it from the numerous other Neuenburgs, especially Neuenburg am Rhein. The Romansh language uses the French Neuchâtel, and occasionanally Neuschatel[13] and Neufchâtel; contemporary Italian largely uses the French name as well, but occasionally the historic Neocastello is seen.[14]

Regionally, the Romand (Arpitan) name for the town is Nôchâtél in the broad Orthographe de référence B[15] and is pronounced N'tchati [n̩.t͡ʃa.ˈti] locally,[16][17] N'tchatai [n̩.t͡ʃa.ˈtai] in La Sagne,[18] N'tchaté [n̩.t͡ʃa.ˈte] in Les Planchettes[18] and Nchaté [n̩.ʃa.ˈte] or Ntchaté in Les Éplatures.[18]

Historic names

editThe Neo-Latin name for Neuchâtel is the Greek-derived Neocomum,[19][9] and this gives the adjective neocomensis which appears on the seal of the University of Neuchâtel[9] (in Universitas Neocomensis Helvetiorum) and the English adjective Neocomian, a term for a former stratigraphic stage of the Early Cretaceous.[20] Other Latin names seen historically include Novum castellum in 1011[21] (upon the presentation of Neuchâtel Castle by Rudolph III of Burgundy to his wife Ermengarde[21]) and Novum Castrum in 1143.[21]

Historic French names included Nuefchastel (attested in 1251),[21] Neufchastel (1338),[21] and Neufchatel,[9] with modern Neuchâtel in use by 1750.[21] In the Franche-Comté, the city was also called Neuchâtel-outre-Joux ("Neuchâtel beyond Joux") to distinguish it from another Neuchâtel in that region, now called Neuchâtel-Urtière.

German names of the town included Nienburg,[9] Nuvenburch (attested in 1033)[21] Nüwenburg,[9] Welschen Nüwenburg,[13][b] Newenburg am See[13] ("Newcastle by the lake") and Welschneuburg,[13] with modern Neuenburg established by 1725.[21]

Italian names included Neocastello[22] (which is occasionally seen in contemporary contexts[14]) and Nuovo Castello.[23]

History

editPrehistory

editThe oldest traces of humans in the municipal area are the remains of a Magdalenian hunting camp, which was dated to 13,000 BC. It was discovered in 1990 during construction of the A5 motorway at Monruz (La Coudre). The site was about 5 m (16 ft) below the main road. Around the fire pits carved flints and bones were found. In addition to the flint and bone artifacts three tiny earrings from lignite were found. The earrings may have served as symbols of fertility and represent the oldest known art in Switzerland. This first camp was used by Cro-Magnons to hunt horse and reindeer in the area. Azilian hunters had a camp at the same site at about 11,000 BC. Since the climate had changed, their prey was now deer and wild boar.

During the 19th century, traces of some stilt houses were found in Le Cret near the red church. However, their location was not well documented and the site was lost. In 1999, during construction of the lower station of the funicular railway, which connects the railway station and university, the settlement was rediscovered. It was later determined to be a Cortaillod culture (middle Neolithic) village. According to dendrochronological studies, some of the piles were from 3571 BC.[24]

A Hallstatt grave (early Iron Age) was found in the forest of Les Cadolles.

Antiquity

editAt Les Favarger a Gallo-Roman and at André Fontaine a small coin depot were discovered. In 1908, an excavation at the mouth of the Serrière discovered Gallo-Roman baths from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD.

Middle Ages

editOne of the most important Merovingian cemeteries in the canton was discovered at Les Battieux in Serrières. In 1982, 38 graves dating from the 7th century were excavated many of which contained silver-inlaid or silver-plated belt buckles. Also in Serrières at the church of Saint-Jean, the remains of a 7th-century shrine were excavated.[24]

In 1011, Rudolph III of Burgundy presented a Novum castellum or new castle on the lake shore to his wife, Ermengarde. It was long assumed that this new castle replaced an older one, but nothing about its location or design is known. At the time of this gift Neuchâtel was probably the center of a newly created royal court, which was recently developed to complement the other royal estates which managed western estates of the kings of Burgundy.[24]

The first counts of Neuchâtel were named shortly afterwards, and in 1214 their domain was officially dubbed a city.

Early modern era

editFor three centuries, the County of Neuchâtel flourished, and in 1530, the people of Neuchâtel accepted the Reformation, and their city and territory were proclaimed to be indivisible from then on. Future rulers were required to seek investiture from the citizens.

With increasing power and prestige, Neuchâtel was raised to the level of a principality at the beginning of the 17th century. On the death in 1707 of Marie d'Orleans-Longueville, duchess de Nemours and Princess of Neuchâtel, the people had to choose her successor from among fifteen claimants. They wanted their new prince first and foremost to be a Protestant, and also to be strong enough to protect their territory but based far enough away to leave them to their own devices. Louis XIV actively promoted the many French pretenders to the title, but the Neuchâtelois people passed them over in favour of King Frederick I of Prussia, who claimed his entitlement in a rather complicated fashion through the Houses of Orange and Nassau. With the requisite stability assured, Neuchâtel entered its golden age, with commerce and industry (including watchmaking and lace) and banking undergoing steady expansion.

Modern Neuchâtel

editAt the beginning of the 19th century, Prussia sought to obtain Hanover whilst still maintaining neutrality and abstaining from the wars waged by Napoleon. Frederick William III had hoped that Prussia could receive the Electorate of Hanover from France only after the event of a British defeat and a resulting treaty, lest Prussia be forced to enter war alongside France against Britain over the territory, with which Britain had been in personal union since 1714. To achieve these aims of receiving Hanover with a simultaneous preservation of neutrality, Prussia offered to give up certain exclaves to the French, however, Napoleon exploited Prussia's politically isolated position and forced Prussia to give up more than had been hoped, partake in the Continental Blockade, and to officially annex Hanover in the Treaty of Paris on 15 February 1806, resulting in the cession of the principality of Neuchâtel to Napoleon. Napoleon's field marshal, Berthier, became Prince of Neuchâtel, building roads and restoring infrastructure, but never actually setting foot in his domain. After the fall of Napoleon, Frederick William III of Prussia reasserted his rights by proposing that Neuchâtel be linked with the other Swiss cantons (to exert better influence over all of them). On 12 September 1814, Neuchâtel became the capital of the 21st canton, but also remained a Prussian principality. It took a bloodless revolution in the decades following for Neuchâtel to shake off its princely past and declare itself, on 1 March 1848, a republic within the Swiss Confederation. Prussia yielded its claim to the canton following the 1856–1857 Neuchâtel Crisis.

On 1 January 2021 the former municipalities of Corcelles-Cormondrèche, Peseux and Valangin merged into the municipality of Neuchâtel.[6] Corcelles-Cormondrèche was first mentioned in the historical record in 1092 as Curcellis. Around 1220 it was mentioned as Cormundreschi.[25] Peseux was first mentioned in 1195 as apud Pusoz though this comes from a 15th-century copy of an earlier document. In 1278 it was mentioned as de Posoys.[26] Valangin was first mentioned in 1241 as de Valengiz.[27]

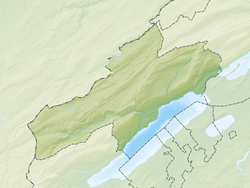

Geography

editBefore the 2021 merger of municipalities, Neuchâtel had an area, as of 2009[update], of 18.1 square kilometers (7.0 sq mi). Of this area, 1.84 km2 (0.71 sq mi) or 10.2% was used for agricultural purposes, while 9.74 km2 (3.76 sq mi) or 53.8% was forested. Of the rest of the land, 6.42 km2 (2.48 sq mi) or 35.5% was settled (buildings or roads), 0.03 km2 (7.4 acres) or 0.2% was either rivers or lakes and 0.02 km2 (4.9 acres) or 0.1% was unproductive land.[28]

Of the built up area, industrial buildings made up 2.2% of the total area while housing and buildings made up 18.0% and transportation infrastructure made up 10.1%. while parks, green belts and sports fields made up 4.3%. Out of the forested land, 51.8% of the total land area was heavily forested and 2.0% is covered with orchards or small clusters of trees. Of the agricultural land, 1.4% was used for growing crops and 8.0% was pastures. All the water in the municipality is in lakes.[28]

The city is located on the northwestern shore of Lake Neuchâtel, a few kilometers east of Peseux and west of Saint-Blaise. Above Neuchâtel, roads and train tracks rise steeply into the folds and ridges of the Jura range—known within the canton as the Montagnes neuchâteloises. Like the continuation of the mountains on either side, this is wild and hilly country, not exactly mountainous compared with the high Alps further south but still characterized by remote, windswept settlements and deep, rugged valleys. It is also the heartland of the celebrated Swiss watchmaking industry, centered on the once-famous towns of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle, which both rely heavily on their horological past to draw in visitors. The river Doubs marks for a part the border with France, set down in a gorge and forming along its path a waterfall, the Saut du Doubs, and lake, the Lac des Brenets.

The municipality was the capital of Neuchâtel District, until the district level of administration was eliminated on 1 January 2018.[29]

Climate

edit| Climate data for Neuchâtel, elevation 485 m (1,591 ft), (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

19.8 (67.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

5.8 (42.4) |

2.6 (36.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.7 (53.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69.4 (2.73) |

57.8 (2.28) |

62.6 (2.46) |

67.4 (2.65) |

86.9 (3.42) |

86.7 (3.41) |

91.6 (3.61) |

99.4 (3.91) |

77.4 (3.05) |

87.6 (3.45) |

76.3 (3.00) |

92.5 (3.64) |

955.6 (37.62) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 9.8 (3.9) |

7.9 (3.1) |

3.9 (1.5) |

0.4 (0.2) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.5 (1.0) |

8.7 (3.4) |

33.2 (13.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.9 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 8.5 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 118.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 3.4 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 11.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 76 | 68 | 65 | 67 | 67 | 64 | 68 | 73 | 80 | 82 | 83 | 73 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 52.5 | 92.4 | 157.0 | 187.8 | 207.7 | 231.7 | 254.0 | 233.9 | 178.6 | 107.7 | 56.2 | 40.1 | 1,799.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 20 | 34 | 45 | 49 | 48 | 54 | 58 | 57 | 50 | 34 | 22 | 16 | 43 |

| Source 1: NOAA[30] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: MeteoSwiss[31] | |||||||||||||

Politics

editCoat of arms

editThe blazon of the municipal coat of arms is Or, an Eagle displayed Sable beaked, langued and membered Gules, escutcheon Or, on a pale Gules three Chevrons Argent.[32]

Administrative divisions

editGovernment

editThe Municipal Council (Conseil communal, CC) constitutes the executive government of the City of Neuchâtel and operates as a collegiate authority. It is composed of five councillors (French: Conseiller communal/ Conseillère communale), each presiding over administrational sections and services comprising the related commissions. The president of the executive department acts as mayor (président(e)) and is nominated annually in a tournus by the collegiate itself. In the mandate period January 2021 – June 2022 (l'année administrative) the Municipal Council is presided by Madame la présidente Violaine Blétry-de Montmollin. Departmental tasks, coordination measures and implementation of laws decreed by the General Council (parliament) are carried by the Municipal Council. The regular election of the Municipal Council by any inhabitant valid to vote is held every four years. Any resident of Neuchâtel allowed to vote can be elected as a member of the Municipal Council. Due to the constitution by canton of Neuchâtel not only Swiss citizens have the right to vote and elect and being elected on communal and cantonal level, but also foreigners with a residence in the canton of Neuchâtel and being resident in the canton of Neuchâtel for at least one year for communal elections and votes, and at least five years of residence in the canton for cantonal elections and votes.[33] The current mandate period is from 2021 to 2024. The delegates are selected by means of a system of proportional representation.[34]

As of 2017[update], Neuchâtel's Municipal Council is made up of two representatives of the PS/SP (Social Democratic Party), two representatives of the PLR/FDP (Les Libéraux-Radicaux), and one member of the PES/GPS (Green Party). The last regular election was held on 25 October 2020.[35]

| Municipal Councilor (Conseiller communal/ Conseillère communale) |

Party | Head of section (Directeur/Directrice de, since) of | Elected since |

|---|---|---|---|

| Violaine Blétry-de Montmollin[CC 1] | PLR | Territorial Development, Economy, Tourism, and Built Heritage (Dicastère du développement territorial, de l'économie, du tourisme et du patrimoine bâti, 2021) | 2016 |

| Thomas Facchinetti[CC 2] | PS | Culture, Integration, and Social Cohesion (Dicastère de la culture, de l'intégration et de la cohésion sociale, 2021) | 2012 |

| Didier Boillat | PLR | Technological Development, Agglomeration, Security, and Finances (Dicastère du développement technologique, de l'agglomération, de la sécurité et des finances, 2021) | 2020 |

| Nicole Baur | Les Verts | Family, Education, Health, and Sport (Dicastère de la famille, de la formation, de la santé et des sports, 2021) | 2020 |

| Mauro Moruzzi | pvl | Sustainable Development, Mobility, Infrastructure, and Energy (Dicastère du développement durable, de la mobilité, des infrastructures et de l'énergie, 2021) | 2020 |

Daniel Veuve is Town Chancellor (chancelier) since 2021 for the City Council.

Parliament

editThe Conseil général (CG) of Neuchâtel for the mandate period of 2020–24

The General Council (Conseil général, CG), the city parliament, holds legislative power. It is made up of 41 members, with elections held every four years. The General Council decrees regulations and by-laws that are executed by the Municipal Council and the administration. The delegates are selected by means of a system of proportional representation.

The sessions of the General Council are public. Unlike members of the Municipal Council, members of the General Council are not politicians by profession, and they are paid a fee based on their attendance. Any resident of Neuchâtel allowed to vote can be elected as a member of the General Council. Due to the constitution of the canton of Neuchâtel not only Swiss citizen have the right to vote and elect and be elected on the communal level, but also foreigners in the canton of Neuchâtel having been resident in the canton of Neuchâtel for at least one year for communal elections and votes, and at least five years of residence in the canton for cantonal elections and votes.[33] The CG holds its meetings in the Town Hall (L'Hôtel de Ville), in the old city on Rue de l'Hôtel de Ville.[37]

The last regular election of the General Council was held on 25 October 2020 for the mandate period (la législature) from 2020 to 2024. Currently the General Council consist of 12 members of The Liberals (PLR/FDP), 11 Les Verts, Ecologie et Liberté members (an alliance of the Green Party (PES/GPS) and others), 10 Social Democratic Party (PS/SP), 5 members of the Green Liberals (pvl/glp), 2 members of the left party solidaritéS, and one of the Swiss Party of Labour (PST-POP/PdA) (Parti Suisse du Travail – Parti Ouvrier et Populaire).[35]

Elections

editNational Council

editIn the 2015 federal election the most popular party was the PS which received 29.3% of the vote. The next four most popular parties were the PLR (22.8%), the UDC (13.6%), the Green Party (12.1%), and the Swiss Party of Labour (10.1%). In the federal election, a total of 8,136 voters were cast, and the voter turnout was 41.4%.[38]

International relations

edit- Neuchâtel is a pilot city of the Council of Europe and the European Commission Intercultural cities programme.[39]

Twin towns – Sister cities

editNeuchâtel is twinned with:[40]

- Aarau, Switzerland, 1997

- Besançon, France, 1975

- Sansepolcro, Italy, 1997

Namesakes

editNeuchâtel was part of the 1998 summit of worldwide cities named "New Castle" with:[41]

|

|

Demographics

editPopulation

editNeuchâtel has a population (as of December 2020[update]) of 33,455.[42] As of 2008[update], 32.1% of the population are resident foreign nationals.[43] Over the last 10 years (2000–2010) the population has changed at a rate of 3.9%. It has changed at a rate of 2.4% due to migration and at a rate of 1% due to births and deaths.[44]

As of 2008[update], the population was 47.7% male and 52.3% female. The population was made up of 10,371 Swiss men (31.5% of the population) and 5,344 (16.2%) non-Swiss men. There were 12,366 Swiss women (37.5%) and 4,892 (14.8%) non-Swiss women.[45] Of the population in the municipality, 8,558 or about 26.0% were born in Neuchâtel and lived there in 2000. There were 5,134 or 15.6% who were born in the same canton, while 7,744 or 23.5% were born somewhere else in Switzerland, and 10,349 or 31.4% were born outside of Switzerland.[46]

As of 2000[update], children and teenagers (0–19 years old) make up 19.3% of the population, while adults (20–64 years old) make up 63.1% and seniors (over 64 years old) make up 17.6%.[44]

As of 2000[update], there were 14,143 people who were single and never married in the municipality. There were 14,137 married individuals, 2,186 widows or widowers and 2,448 individuals who are divorced.[46]

As of 2000[update], there were 15,937 private households in the municipality, and an average of 2. persons per household.[44] There were 7,348 households that consist of only one person and 547 households with five or more people. In 2000[update], a total of 15,447 apartments (89.9% of the total) were permanently occupied, while 1,429 apartments (8.3%) were seasonally occupied and 311 apartments (1.8%) were empty.[47] As of 2009[update], the construction rate of new housing units was 2.5 new units per 1000 residents.[44]

As of 2003[update] the average price to rent an average apartment in Neuchâtel was 921.35 Swiss francs (CHF) per month (US$740, £410, €590 approx. exchange rate from 2003). The average rate for a one-room apartment was 451.40 CHF (US$360, £200, €290), a two-room apartment was about 675.66 CHF (US$540, £300, €430), a three-room apartment was about 825.15 CHF (US$660, £370, €530) and a six or more room apartment cost an average of 1647.88 CHF (US$1320, £740, €1050). The average apartment price in Neuchâtel was 82.6% of the national average of 1116 CHF.[48] The vacancy rate for the municipality, in 2010[update], was 0.53%.[44]

Historical population

editThe historical population is given in the following chart:[24]

| Historical Population Data[24] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total Population | French Speaking | German Speaking | Protestant | Catholic | Other | Jewish | Islamic | No religion given | Swiss | Non-Swiss |

| 1850 | 7,901 | 7,098 | 789 | 7,068 | 833 | ||||||

| 1870 | 12,934 | 11,012 | 2,327 | 11,306 | 2,284 | ||||||

| 1888 | 16,565 | 11,511 | 4,651 | 13,973 | 2,387 | 143 | 94 | 14,447 | 2,118 | ||

| 1900 | 21,195 | 15,566 | 4,596 | 17,548 | 3,500 | 232 | 80 | 18,108 | 3,087 | ||

| 1910 | 24,171 | 17,543 | 5,161 | 19,750 | 3,944 | 476 | 111 | 20,625 | 3,546 | ||

| 1930 | 22,668 | 17,027 | 4,612 | 18,615 | 3,638 | 306 | 63 | 20,640 | 2,028 | ||

| 1950 | 27,998 | 21,897 | 4,784 | 21,439 | 5,891 | 308 | 58 | 26,307 | 1,691 | ||

| 1970 | 38,784 | 26,200 | 5,117 | 21,882 | 15,262 | 2,352 | 59 | 76 | 791 | 30,012 | 8,772 |

| 1990 | 33,579 | 24,579 | 2,467 | 13,198 | 13,305 | 4,462 | 55 | 481 | 5,634 | 24,250 | 9,329 |

| 2000 | 32,914 | 25,881 | 1,845 | 10,296 | 10,809 | 3,767 | 58 | 1,723 | 7,549 | 22,801 | 10,113 |

Language

editMost of the population (as of 2000[update]) speaks French (25,881 or 78.6%) as their first language, German is the second most common (1,845 or 5.6%) and Italian is the third (1,421 or 4.3%). There are about six people who speak Romansh.[46]

Religion

editNeuchâtel was historically Protestant, but Catholics have since formed a plurality due to immigration. From the 2000 census[update], 10,809 or 32.8% were Roman Catholic, while 9,443 or 28.7% belonged to the Swiss Reformed Church. Of the rest of the population, there were 374 members of an Orthodox church (or about 1.14% of the population), there were 80 individuals (or about 0.24% of the population) who belonged to the Christian Catholic Church, and there were 1,756 individuals (or about 5.34% of the population) who belonged to another Christian church. There were 58 individuals (or about 0.18% of the population) who were Jewish, and 1,723 (or about 5.23% of the population) who were Muslim. There were 99 individuals who were Buddhist, 100 individuals who were Hindu and 59 individuals who belonged to another church. 7,549 (or about 22.94% of the population) belonged to no church, are agnostic or atheist, and 1,717 individuals (or about 5.22% of the population) did not answer the question.[46]

Crime

editIn 2014 the crime rate, of crimes listed in the Swiss Criminal Code, in Neuchâtel was 140.4 per thousand residents. During the same period, the rate of drug crimes was 16.3 per thousand residents. The rate of violations of immigration, visa and work permit laws was 5.7 per thousand residents.[49]

Economy

editNeuchâtel is a centre of the watch industry, and is also the site of micro-technology and high-tech industries. It is home to research centres and organizations such as the Swiss Center for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM),[50] Microcity innovation pole,[51] University of applied Sciences HE-Arc in Engineering[52] and also Philip Morris International's Cube.[53] The apparel company heidi.com also established its headquarters in the city.

As of 2010[update], Neuchâtel had an unemployment rate of 7.5%. As of 2008[update], there were 46 people employed in the primary economic sector and about 14 businesses involved in this sector. 5,658 people were employed in the secondary sector and there were 261 businesses in this sector. 20,472 people were employed in the tertiary sector, with 1,955 businesses in this sector.[44] There were 16,353 residents of the municipality who were employed in some capacity, of which women made up 45.4% of the workforce.

In 2008[update] the total number of full-time equivalent jobs was 21,624. The number of jobs in the primary sector was 38, of which 20 were in agriculture and 18 were in forestry or lumber production. The number of jobs in the secondary sector was 5,433 of which 4,234 or (77.9%) were in manufacturing, 9 or (0.2%) were in mining and 1,022 (18.8%) were in construction. The number of jobs in the tertiary sector was 16,153. In the tertiary sector; 2,397 or 14.8% were in wholesale or retail sales or the repair of motor vehicles, 796 or 4.9% were in the movement and storage of goods, 919 or 5.7% were in a hotel or restaurant, 766 or 4.7% were in the information industry, 1,077 or 6.7% were the insurance or financial industry, 1,897 or 11.7% were technical professionals or scientists, 1,981 or 12.3% were in education and 2,633 or 16.3% were in health care.[54]

In 2000[update], there were 15,535 workers who commuted into the municipality and 6,056 workers who commuted away. The municipality is a net importer of workers, with about 2.6 workers entering the municipality for every one leaving.[55] Of the working population, 33.7% used public transportation to get to work, and 43.4% used a private car.[44]

Education

editNeuchâtel is home to the French-speaking University of Neuchâtel. The university has five faculties and more than a dozen institutes, including arts and human sciences, natural sciences, law, economics and theology. For the 2005–2006 academic year, 3,595 students (1,987 women and 1,608 men) were enrolled. The Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences is the largest school of those that comprise the university of Neuchâtel with 1,500 students. Some courses at the university are taught in English.[citation needed]

Neuchâtel is home to the Éditions Alphil, which is a university press founded in 1996.

Neuchâtel is home to eight libraries: the Bibliothèque de la Faculté des Lettres, the Bibliothèque de l'Institut d'ethnologie et du Musée d'ethnographie, the Bibliothèque de la Faculté des Sciences, the Bibliothèque de droit, the Bibliothèque des sciences économiques, the Bibliothèque de la Faculté de théologie, the Service de coordination des bibliothèques and the Haute école Arc – Santé. There was a combined total (as of 2008[update]) of 736,773 books or other media in the libraries, and in the same year a total of 58,427 items were loaned out.[56]

In Neuchâtel about 11,076 or (33.7%) of the population have completed non-mandatory upper secondary education, and 5,948 or (18.1%) have completed additional higher education (either university or a Fachhochschule). Of the 5,948 who completed tertiary schooling, 43.6% were Swiss men, 28.4% were Swiss women, 16.4% were non-Swiss men and 11.6% were non-Swiss women.[46]

In the canton of Neuchâtel most municipalities provide two years of non-mandatory kindergarten, followed by five years of mandatory primary education. The next four years of mandatory secondary education is provided at thirteen larger secondary schools, which many students travel out of their home municipality to attend.[57] During the 2010–11 school year, there were 27 kindergarten classes with a total of 527 students in Neuchâtel. In the same year, there were 78 primary classes with a total of 1,424 students.[58] Secondary schools include the Lycée Jean-Piaget.

Apart from one International Montessori school for kids up to age 11 offering an English and a French class there is no international school in Neuchâtel. Neuchâtel Junior College was founded in 1956 as a non-profit foundation of the Ville de Neuchâtel to provide a unique international education. Neuchâtel Junior College is a one-year school annually welcoming over 100 students in their final pre-university year to study the Ontario Grade 12 curriculum as well as Advanced Placement.

As of 2000[update], there were 3,859 students in Neuchâtel who came from another municipality, while 346 residents attended schools outside the municipality.[55]

Transport

editNeuchâtel has local public transport provided by Transports publics neuchâtelois (transN), the result of the 2012 merge between Transports publics du littoral neuchâtelois (TN) and Transports régionaux neuchâtelois (TRN). transN operates the Neuchâtel trolleybus system, a funicular, an interurban light rail line to Boudry and other lines in the Canton of Neuchâtel. It serves 25'650'170 people in 2022.[59]

Neuchâtel railway station forms part of one of Switzerland's most important railway lines, the Jura foot railway (Olten–Genève-Aéroport), which is operated by the Swiss Federal Railways. The station is also a junction for several other lines, including a cross-border line served by the TGV (High Speed Train), with direct trains linking Neuchâtel to Paris in four hours.

Neuchâtel's airport is about 6 km (3.7 mi) away from the center of the city and it takes 9 minutes to get into town with the direct tramway. It is a small airport that does not offer commercial flights. Neuchâtel is also linked to four international airports: Bern, Geneva, Basel and Zürich which are respectively 58 km (36 mi), 122 km (76 mi), 131 km (81 mi) and 153 km (95 mi) away by car. Geneva and Zürich airports both have direct trains to Neuchâtel, connecting the cities respectively in 1h 17min and 1h 49min.[60] Three funiculars serve the city:

- The Funambule, linking the lower part of the town, near the university, to the railway station

- The Funiculaire Ecluse–Plan[61]

- The Funiculaire La Coudre–Chaumont[62]

The Société de Navigation sur les Lacs de Neuchâtel et Morat SA is the boat company which serves 17 towns on Lake Neuchâtel, 6 towns on Lake Murten and 7 towns on Lake Bienne from 6:30am to 9pm. Some boats offer free wireless internet connections.[63]

Sights

editHeritage sites of national significance

editThere are 34 sites in Neuchâtel that are listed as Swiss heritage site of national significance. The entire old city of Neuchâtel, the urban village of Corcelles the small city of Valangin, the Bussy/Le Sorgereux region and the La Borcarderie region are part of the Inventory of Swiss Heritage Sites.[64]

Architecture

editNeuchâtel's Old Town has about 140 street fountains, a handful of which date from the 16th century. The Place des Halles is overlooked by Louis XIV architecture – shuttered façades and the turreted orioles of the 16th-century Maison des Halles. To the east, on Rue de l’Hôpital, is the grand 1790 Hôtel de Ville (Town Hall), designed by Louis XVI's chief architect Pierre-Adrien Paris.

The center of the Old Town is located at the top of the hill, accessed by the steeply winding Rue du Château. The Collégiale church, begun in 1185 and consecrated in 1276, is an example of early Gothic. The east end of the church has three Norman apses. The main entrance, to the west, is crowned by a giant rose window of stained glass. Within the vaulted interior, the transept is lit by a lantern tower. The Cenotaph of the Counts of Neuchâtel is located on the north wall of the choir. Begun in 1372, and the only artwork of its kind to survive north of the Alps, the monument comprises fifteen near-life-size painted statues of various knights and ladies from Neuchâtel's past, framed by 15th-century arches and gables.[citation needed] Beside the church is the Castle, begun in the 12th century and still in use as the offices of the cantonal government. The nearby turreted Prison Tower, which is the remains of a medieval bastion, has panoramic views over the town, along with models of Neuchâtel in different eras.[citation needed]

Museums

editNeuchâtel has several museums, including the Laténium, an archeology museum focusing on the prehistorical times in the region of Neuchâtel and Hauterive, particularly the La Tène culture, with the eponym site being a few kilometers away; the Musée d'ethnographie de Neuchâtel (MEN), an ethnography museum; and the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, which houses the Automates Jaquet-Droz (Jaquet-Droz Mechanical Figurines).

Culture

editDuring the summer of 2002, Neuchâtel was one of five sites which held Expo.02, the sixth Swiss national exhibition, which was subject to financial controversy.[clarification needed] The Neuchâtel International Fantastic Film Festival is held every year to celebrate fantastic cinema from around the world. The festival of the Fête des Vendanges, representing the wine harvest, is held traditionally in late September.[65]

Sport

editNeuchâtel Xamax is the most important football club based in Neuchâtel. It was created in 1970 through a merger between FC Cantonal (1906) and FC Xamax (1916). The club plays in Swiss Super League, the highest Swiss football league. The club plays its home matches at the Stade de la Maladière.

HC Uni Neuchâtel plays in the MySports League, the third tier of the Swiss hockey league system. Their home games are held in the 7,000-seat Littoral.

Union Neuchâtel Basket is the city's top basketball team, which plays in the Championnat LNA, Switzerland's only professional basketball league.

Notable people

editWilliam Ritter, Jean Piaget, Marcel Junod, Robert Miles and Yves Larock were all born in Neuchâtel. Friedrich Dürrenmatt lived in Neuchâtel the last 30 years of his life. Prens Sabahaddin, was an Ottoman sociologist and thinker of the Ottoman dynasty, lived in Neuchâtel the last 25 years of his life.

Hungarian writer Ágota Kristóf moved to Neuchâtel after fleeing repression following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. She lived in the city for the rest of her life, learning and writing books in French.

Canadian illustrator John Howe, who illustrated J. R. R. Tolkien's work and participated in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy as chief conceptual designer, lives in the city. It was also the site of a secret first meeting between French novelist Honoré de Balzac and the married woman who later became his wife, Eveline Hanska.[66] Roger Schutz, founder of the Taizé Community in France, was born on 12 May 1915 at the village of Provence near Neuchâtel. He was stabbed to death on 16 August 2005 by a mentally deranged woman during a prayer meeting in Taizé's Church of Reconciliation.[citation needed]

The de Pury family, a Prussian noble family, is from Neuchâtel. Swiss merchant and philanthropist David de Pury, a native of Neuchâtel, left a large fortune to the city for public works and charities. His relative, James-Ferdinand de Pury, also a merchant and philanthropist, bequest his villa to house the town's ethnography museum. Other members of the family who were born or resided in the town include explorer and colonist Jean-Pierre Pury, winemaker and diplomat Frédéric Guillaume de Pury, painter Edmond Jean de Pury, and biblical scholar Albert de Pury.

The de Castello family, a French noble family, including winemakers Hubert de Castella and Paul de Castella, is from Neuchâtel. The de Montmollin family, including the Protestant minister David-François de Montmollin, are also from the town. Frédéric Louis Godet (1812–1900) was another Swiss Protestant theologian who was born and died in Neuchâtel;[67] as was Jean-Frédéric Osterwald (1663–1747), a further Protestant pastor.[68]

French counter-revolutionary Louis Fauche-Borel was born and died in Neuchâtel, and François Bigot, the last Intendant of New France, relocated to there after being exiled from France.

Abraham Louis Breguet, the founder of the Breguet watch company and an esteemed inventor, often regarded as the father of modern horology, was born in Neuchâtel. The company still maintains its headquarters at L'Abbaye, about 40 km southwest of Neuchâtel.

The psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Silvio Fanti was born in Neuchâtel in 1919. He founded and developed Micropsychoanalysis, a new school of psychoanalysis. Another important psychiatrist, Gottlieb Burckhardt, practiced in Neuchâtel. Alexander Agassiz (1835–1910), was an American scientist and engineer from the town.[69]

Didier Burkhalter, 94th President of the Swiss Confederation was born in Neuchâtel, as was Logitech founder Daniel Borel.

Footballers Max Abegglen,[70] Jayson Leutwiler, and Yann Kasaï, as well as Swiss Olympic field hockey player Albert Piaget were all born in Neuchâtel. It is also the current residence of French tennis players Richard Gasquet, Gilles Simon and Florent Serra, as well as the Mexican Formula 1 driver Sergio Pérez, and the artist and designer Ini Archibong.[71][72][73] Anthropologist, artist, and filmmaker Véréna Paravel was also born in Neuchâtel.[74] It is the birthplace of explorer and lecturer Raphaël Domjan.[75]

See also

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ The city is one of the Newcastles of the World[9] and hosted the 2000 Newcastles of the World summit.[10]

- ^ German Welsch- refers to the inhabitants of Romandy (Welschschweiz or Welschland[13]) and is prefixed to several German-language placenames in Switzerland and beyond (e.g. Welschenrohr near the language border).

References

edit- ^ a b "Arealstatistik Standard - Gemeinden nach 4 Hauptbereichen". Federal Statistical Office. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Ständige Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeitskategorie Geschlecht und Gemeinde; Provisorische Jahresergebnisse; 2018". Federal Statistical Office. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "NEUCHÂTEL, LAKE English Definition and Meaning | Lexico.com". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Neuchâtel". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Neuchâtel". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Applikation der Schweizer Gemeinden". bfs.admin.ch. Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Bilanz der ständigen Wohnbevölkerung (Total) nach Bezirken und Gemeinden". Federal Statistical Office. 26 March 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "FUSION NEUCHÂTEL". Neuchâtel. 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Repères historiques: Le Nom". Site officiel de la Ville de Neuchâtel (in French). Centre électronique de gestion de la Ville de Neuchâtel. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Newcastles of the World: About. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Walter, Henriette. "Une germanique influence" in Le Français dans tous les sens. Robert Laffont: 1988. ISBN 2253140015

- ^ de Beaurepaire, François (1979). Les Noms des communes et anciennes paroisses de la Seine-Maritime (in French). Paris: A. and J. Picard. p. 8. ISBN 2-7084-0040-1. OCLC 6403150.

- ^ a b c d e "Neuchâtel". Historische Lexikon der Schweiz (in German, French, Italian, and Romansh). 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ a b "La settimana del gusto, Gastronomia per i giovani". Gout.ch (in Italian). 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Stich, Dominique (2003). Dictionnaire francoprovençal-français (in French and Arpitan). Thonon-les-Bains: Editions Le Carré.

- ^ Le patois neuchâtelois. Neuchâtel: Imprimerie Wolfrath et Cie. 1895.

- ^ Kristol, Andres (2005). Dictionnaire toponymique des communes suisses (in French, German, and Italian). Lausanne: Éditions Payot. ISBN 2-601-03336-3.

- ^ a b c Rilliot, Joël. "Lexique français-patois" (PDF) (in French and Arpitan). p. 76. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Hofmann, Johann Jacob (1698). "Nomenclator". Lexicon Universale (in Latin). Lugduni Batavorum: Jacob Hackium et al.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Neocomian". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jelmini, Jean-Pierre (8 September 2021). "Neuchâtel (commune)". Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (in French, German, and Italian). Académie suisse des sciences humaines et sociales. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Umberto Tirelli (24 May 2010). "Neuchâtel, valle verde tra Dürrenmatt e cacao". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ De Jacobis, Nicola (1845). "Nuovo Castello". Dizionario universale portatile di lingua italiana, geografia, storia sacra, ecclesiastica e profana, mitologia, medicina, chirurgia, veterinaria, farmaceutica, fisica, chimica, zoologia, botanica, mineralogia, scienze, arti, mestieri, ecc., vol. 2, pag. 571, 1ª colonna in basso (in Italian). Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Neuchâtel in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Corcelles-Cormondrèche in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Peseux in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Valangin in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b Swiss Federal Statistical Office-Land Use Statistics 2009 data (in German) accessed 25 March 2010

- ^ Amtliches Gemeindeverzeichnis der Schweiz (in German) accessed 15 February 2018

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ "Climate Normals Neuchâtel (Reference period 1991–2020)" (PDF). Swiss Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology, MeteoSwiss. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Flags of the World.com accessed 25-October-2011

- ^ a b "Voter? Mode d'emploi" (official site) (in French). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Ville de Neuchâtel. 2016. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ "Réglementation" (official site) (in French). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Ville de Neuchâtel. 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Élections communales 2020" (official site) (in French). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Ville de Neuchâtel. 25 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "Conseil communal" (official site) (in French). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Ville de Neuchâtel. 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ "Conseil général" (official site) (in French). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Secrétariat du Conseil général. 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ "Nationalratswahlen 2015: Stärke der Parteien und Wahlbeteiligung nach Gemeinden" (XLS) (official statistics) (in German and French). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Statistical Office, FSO. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Intercultural city: Neuchâtel Canton, Switzerland". Council of Europe. 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ "VILLES JUMELÉES" (official site) (in French). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Ville de Neuchâtel. 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ "Website of the official convention of cities named "new castle"". newcastlesoftheworld.com. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit". bfs.admin.ch (in German). Swiss Federal Statistical Office - STAT-TAB. 31 December 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office – Superweb database – Gemeinde Statistics 1981–2008 (in German) accessed 19 June 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g Swiss Federal Statistical Office accessed 25-October-2011

- ^ Canton of Neuchâtel Statistics Archived 5 December 2012 at archive.today, République et canton de Neuchâtel – Recensement annuel de la population (in German) accessed 13 October 2011

- ^ a b c d e STAT-TAB Datenwürfel für Thema 40.3 – 2000 Archived 9 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine (in German) accessed 2 February 2011

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office STAT-TAB – Datenwürfel für Thema 09.2 – Gebäude und Wohnungen Archived 7 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine (in German) accessed 28 January 2011

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office-Rental prices 2003 data (in German) accessed 26 May 2010

- ^ Statistical Atlas of Switzerland accessed 5 April 2016

- ^ "Swiss Center for Electronics and Microtechnology". csem.ch.

- ^ "IMT homepage". epfl.ch.

- ^ "Engineering – Haute-Ecole Arc". he-arc.ch. 17 May 2023.

- ^ "Philip Morris International bets big on the future of smoking". Forbes. 28 May 2014.

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office STAT-TAB Betriebszählung: Arbeitsstätten nach Gemeinde und NOGA 2008 (Abschnitte), Sektoren 1–3 Archived 25 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine (in German) accessed 28 January 2011

- ^ a b Swiss Federal Statistical Office – Statweb Archived 4 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in German) accessed 24 June 2010

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office, list of libraries (in German) accessed 14 May 2010

- ^ EDK/CDIP/IDES (2010). Kantonale Schulstrukturen in der Schweiz und im Fürstentum Liechtenstein / Structures Scolaires Cantonales en Suisse et Dans la Principauté du Liechtenstein (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Statistical Department of the Canton of Neuchâtel Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Mémento de l'année scolaire 2010/2011 (in French) accessed 17 October 2011

- ^ "transN - RAPPORT DE GESTION 2022" (PDF). 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ "Bienvenue sur l'Aéroport de Neuchâtel (LSGN)". neuchatel-airport.ch.

- ^ "TN Ecluse – Plan". Funimag. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "La Coudre – Chaumont". Funimag. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "Bienvenue à bord" (in French). navig.ch. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ "Swiss inventory of cultural property of national and regional significance". A-Objects. Federal Office for Cultural Protection (BABS). 1 January 2017. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ Programme de la Fête des vendanges de Neuchâtel. Fete-des-vendanges.ch. Retrieved on 2013-09-07.

- ^ Maurois, André. Prometheus: The Life of Balzac. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1965. ISBN 0-88184-023-8. Page 228.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 171–172.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 358.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 366–367.

- ^ "Olympic Results – Max Abegglen". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Sergio Pérez a été séduit par Neuchâtel". Le Matin (in French). 20 June 2012. ISSN 1018-3736. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Ini Archibong, designer extraordinaire". House of Switzerland. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Evans, Christina Ohly (30 August 2024). "Ini Archibong's guide to the quiet cool of Neuchâtel". Financial Times. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor". documenta14.de. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Bio | Raphaël Domjan".

Further reading

edit- "Neuchâtel". Switzerland. Coblenz: Karl Baedeker. 1863.

External links

edit- Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). p. 424.

- City of Neuchâtel official website

- (in French) Transports Publics du Littoral Neuchâtelois

- Museums

- Neuchâtel Tourism Office