The Lake Miwok language is an extinct language of Northern California, traditionally spoken in an area adjacent to the Clear Lake. It is one of the languages of the Clear Lake Linguistic Area, along with Patwin, East and Southeastern Pomo, and Wappo.[2]

| Lake Miwok | |

|---|---|

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Lake County, California |

| Ethnicity | Lake Miwok |

| Extinct | 1990s[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | lmw |

| Glottolog | lake1258 |

| ELP | Lake Miwok |

| |

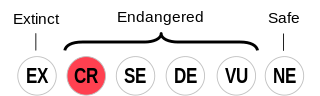

Lake Miwok is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Phonology

editVowels

edit| Short | Long | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | |

| High (close) | i | u | iː | uː |

| Mid | e | o | eː | oː |

| Low (open) | a | aː | ||

Consonants

edit| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | plain | p | ⟨t⟩ t̻ | ⟨ṭ⟩ t̠̺ | k | ʔ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ | ⟨tʰ⟩ t̻ʰ | ⟨ṭʰ⟩ t̠̺ʰ | kʰ | ||||

| ejective | pʼ | ⟨tʼ⟩ t̻ʼ | ⟨ṭʼ⟩ t̠̺ʼ | kʼ | ||||

| voiced | b | ⟨d⟩ d̺ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s | ⟨ṣ⟩ ʃ | ⟨ł⟩ ɬ | h | |||

| ejective | ⟨ƛʼ⟩ t͡ɬʼ | |||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | ⟨c⟩ t͡s | ⟨č⟩ t͡ʃ | |||||

| ejective | ⟨cʼ⟩ t͡sʼ | ⟨čʼ⟩ t͡ʃʼ | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||

| Approximant | w | l (r) | j | |||||

The consonant inventory of Lake Miwok differs substantially from the inventories found in the other Miwok languages. Where the other languages only have one series of plosives, Lake Miwok has four: plain, aspirated, ejective and voiced. Lake Miwok has also added the affricates č, c, čʼ, cʼ, ƛʼ and the liquids r and ł. These sounds appear to have been borrowed through loanwords from other, unrelated languages in the Clear Lake area, after which they spread to some native Lake Miwok words.[2][3]

Grammar

editThe word order of Lake Miwok is relatively free, but SOV (subject–object–verb) is the most common order.[4]

Verb morphology

editPronominal clitics

edit| Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | ka | ʔic | ma, ʔim | |

| 2nd person | ʔin | moc | mon | |

| 3rd person | non-reflexive | ʔi | koc | kon |

| reflexive | hana | hanakoc | hanakon | |

| indefinite | ʔan | |||

In her Lake Miwok grammar, Callaghan reports that one speaker distinguishes between 1st person dual inclusive ʔoc and exclusive ʔic. Another speaker also remembers that this distinction used to be made by older speakers.[5]

Noun morphology

editCase inflection

editNouns can be inflected for ten different cases:

- the Subjective case marks a noun which functions as the subject of a verb. If the subject noun is placed before the verb, the Subjective has the allomorph -n after vowel (or a vowel followed by /h/), and -Ø after consonants. If it is placed after the verb, the Subjective is -n after vowels and -nu after consonants.

kukú

flea

-n

-subjective

ʔin

2SG

tíkki

forehead

-t

-allative

mékuh

sit

"A flea is sitting on your forehead."

- the Possessive case is -n after vowels and -Ø after consonants

ʔóle

coyote

-n

-possessive

ṣúluk

skin

"coyote skin"

táj

man

-Ø

-possessive

ṣáapa

hair

"the man's hair"

- the Objective case marks a noun which functions as the object of a verb. It has the allomorph -u (after a consonant) or -Ø (after a vowel) when the noun is placed immediately before a verb which contains the 2nd person prefix ʔin- (which then has the allomorph -n attached to the noun preceding the verb; compare the example below) or does not contain any subject prefix at all.

káac

fish

-u

-objective

-n

-2SG

ʔúṭe?

see

"Did you see the fish?"

- It has the allomorph -Ø before a verb containing any other subject prefix:

kawáj

horse

-Ø

-objective

ka

1SG

ʔúṭe

see

"I saw the horse"

- If the object noun does not immediately precede the verb, or if the verb is in the imperative, the allomorph of the Objective is -uc:

káac

fish

-uc

-objective

jolúm

eat

-mi

-imperative

"Eat the fish"

- the allative case is -to or -t depending on the environment. It has a variety of meaning, but often expresses direction towards a goal.

- the locative case -m gives a less specific designation of locality than the Allative, and occurs more rarely.

- the ablative case is -mu or -m depending on the context, and marks direction out of, or away from, a place.

- the instrumental case -ṭu marks instruments, e.g. tumáj-ṭu "(I hit him) with a stick".

- the comitative case -ni usually translates as "along with", but can also be used to coordinate nouns, as in kaʔunúu-ni ka ʔáppi-ni "my mother and my father".

- the vocative case only occurs with a few kinship terms, e.g. ʔunúu "mother (voc)" from ʔúnu "mother".

- the Appositive case is the citation form of nouns.

Possessive clitics

editLake Miwok uses pronominal clitics to indicate the possessor of a noun. Except for the 3d person singular, they have the same shape as the nominative pronominal clitics, but show no allomorphy.

| Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | ka | ʔic | ma | |

| 2nd person | ʔin | moc | mon | |

| 3rd person | non-reflexive | ʔiṭi | koc | kon |

| reflexive | hana | hanakoc | hanakon | |

| indefinite | ʔan | |||

The reflexive hana forms have the same referent as the subject of the same clause, whereas the non-reflexive forms have a different referent, e.g.:

- hana háju ʔúṭe – "He sees his own dog"

- ʔiṭi háju ʔúṭe – "He sees (somebody else's) dog"

Notes

edit- ^ Lake Miwok at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ a b Campbell 1997, p. 336.

- ^ Callaghan 1964, p. 47.

- ^ Callaghan 1965, p. 5.

- ^ Callaghan 1963, p. 75.

References

edit- Callaghan, Catherine A. (1963). A Grammar of the Lake Miwok Language. University of California, Berkeley.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Callaghan, Catherine A. (1964). "Phonemic Borrowing in Lake Miwok". In William Bright (ed.). Studies in Californian Linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 46–53.

- Callaghan, Catherine A. (1965). Lake Miwok Dictionary. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages. The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Callaghan, Catherine A. "Note of Lake Miwok Numerals." International Journal of American Linguistics, vol. 24, no. 3 (1958): 247.

- Keeling, Richard. "Ethnographic Field Recordings at Lowie Museum of Anthropology," 1985. Robert H. Lowie Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley. v. 2. North-Central California: Pomo, Wintun, Nomlaki, Patwin, Coast Miwok, and Lake Miwok Indians

- Lake Miwok Indians. "Rodriguez-Nieto Guide" Sound Recordings (California Indian Library Collections), LA009. Berkeley: California Indian Library Collections, 1993. "Sound recordings reproduced from the Language Archive sound recordings at the Language Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley." In 2 containers.

External links

edit- Lake Miwok language overview at the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages

- Lake Miwok audio recordings at the California Language Archive (login required)

- "Lake Miwok sound recordings". Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2012-07-20.

- OLAC resources in and about the Lake Miwok language

- Lake Miwok basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database