Guangzhou,[a] previously romanized as Canton[6] or Kwangchow,[7] is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China.[8] Located on the Pearl River about 120 km (75 mi) northwest of Hong Kong and 145 km (90 mi) north of Macau, Guangzhou has a history of over 2,200 years and was a major terminus of the Silk Road.[9]

Guangzhou

广州市 Canton; Kwangchow | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: City of Rams, City of Flowers, City of Rice Spike | |

| |

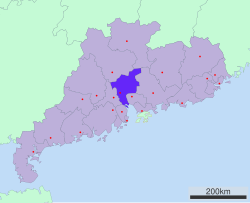

Location of Guangzhou City jurisdiction in Guangdong | |

| Coordinates (Guangdong People's Government): 23°07′48″N 113°15′36″E / 23.13000°N 113.26000°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Guangdong |

| Settled | 214 BC |

| Founded by | Qin dynasty |

| Municipal seat | Yuexiu District |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sub-provincial city |

| • Body | Municipal People's Congress |

| • CCP Secretary | Guo Yonghang |

| • Municipal People's Congress Chairman | Wang Yanshi |

| • Mayor | Sun Zhiyang |

| • CPPCC Chairman | Li Yiwei |

| Area | |

| 7,434.4 km2 (2,870.4 sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 2,256.4 km2 (871.2 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 20,144.1 km2 (7,777.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 21 m (69 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[2] | |

| 18,676,605 | |

| • Density | 2,500/km2 (6,500/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 26,940,000 |

| • Urban density | 12,000/km2 (31,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 32,623,413 |

| • Metro density | 1,600/km2 (4,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Cantonese |

| GDP[3] | |

| • Prefecture-level and sub-provincial city | |

| • Per capita |

|

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (China Standard Time) |

| Postal code | 510000 |

| Area code | (0)20 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-GD-01 |

| License plate prefixes | 粤A |

| City Flower | Bombax ceiba |

| City Bird | Chinese hwamei |

| Languages | Cantonese, Standard Chinese |

| Website | gz.gov.cn |

| Guangzhou | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

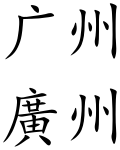

"Guangzhou" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 广州 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 廣州 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | ⓘ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cantonese Yale | ⓘ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Broad Prefecture" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| abbreviation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 穗 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Suì | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cantonese Yale | Seuih | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The port of Guangzhou serves as a transportation hub for Guangzhou, one of China's three largest cities.[10] Guangzhou was captured by the British during the First Opium War and no longer enjoyed a monopoly after the war; consequently it lost trade to other ports such as Hong Kong and Shanghai, but continued to serve as a major entrepôt. Following the Second Battle of Chuenpi in 1841, the Treaty of Nanking was signed between Sir Robert Peel on behalf of Queen Victoria and Lin Zexu on behalf of Emperor Xuanzong and has ceded Hong Kong to the United Kingdom on 26 January 1841 after the agreement of the Convention of Chuenpi.[11]

Guangzhou is at the center of the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macau Greater Bay Area, the most populous built-up metropolitan area in the world, which extends into the neighboring cities of Foshan, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen and part of Jiangmen, Huizhou, Zhuhai and Macau, forming the largest urban agglomeration on Earth with approximately 70 million residents[12] and part of the Pearl River Delta Economic Zone. Administratively, the city holds subprovincial status[13] and is one of China's nine National Central Cities.[14] In the late 1990s and early 2000s, nationals of sub-Saharan Africa who had initially settled in the Middle East and Southeast Asia moved in unprecedented numbers to Guangzhou in response to the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis.[15] The domestic migrant population from other provinces of China in Guangzhou was 40% of the city's total population in 2008. Guangzhou has one of the most expensive real estate markets in China.[16] As of the 2020 census, the registered population of the city's expansive administrative area was 18,676,605 individuals (up 47 percent from the previous census in 2010), of whom 16,492,590 lived in 9 urban districts (all but Conghua and Zengcheng).[2] Due to worldwide travel restrictions at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport, the major airport of Guangzhou, briefly became the world's busiest airport by passenger traffic in 2020.[17] Guangzhou is the fifth most populous city by urban resident population in China after Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen and Chongqing.[18]

In modern commerce, Guangzhou is best known for its annual Canton Fair, the oldest and largest trade fair in China.[19] For three consecutive years (2013–2015), Forbes ranked Guangzhou as the best commercial city in mainland China.[20] Guangzhou is highly ranked as an Alpha (global first-tier) city together with San Francisco and Stockholm.[21] It is a major Asia-Pacific finance hub, ranking 21st globally in the 2020 Global Financial Centres Index.[22] As an important international city, Guangzhou has hosted numerous international and national sporting events, the most notable being the 2010 Asian Games, the 2010 Asian Para Games, and the 2019 FIBA Basketball World Cup. The city hosts 65 foreign representatives, making it the major city hosting the third most foreign representatives in China, after Beijing and Shanghai.[23][24] As of 2020, Guangzhou ranked 10th in the world and 5th in China—after Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Shenzhen—for the number of billionaire residents by the Hurun Global Rich List.[25] Guangzhou is a research and development hub ranking 8th globally as well as 4th in the Asia-Pacific region,[26] and is home to numerous Double First-Class Universities, including Sun Yat-sen University.[27][28][29]

Toponymy

editGuǎngzhōu is the official romanization of the Chinese name 广州. The name of the city is taken from the ancient Guǎng Prefecture after it had become the prefecture's seat of government. The character 廣 or 广 means 'broad' or 'expansive'.

Before acquiring its current name, the town was known as Panyu (Punyü; 番禺), a name still borne by one of Guangzhou's districts not far from the main city. The origin of the name is still uncertain, with 11 various explanations being offered,[30] including that it may have referred to two local mountains.[31][32] The city has also sometimes been known as Guangzhou Fu or Guangfu after its status as the capital of a prefecture. From this latter name, Guangzhou was known to medieval Persians such as Al-Masudi and Ibn Khordadbeh[33] as Khanfu (خانفو).[34] Under the Southern Han, the city was renamed Xingwang Fu (興王府).[35][36]

The Chinese abbreviation for Guangzhou is 穗, pronounced Seoi6 in Cantonese and Suì in Mandarin—although the abbreviation on car license plates, as with the rest of the province, is 粤), after its nickname "City of Rice" (穗城. The city has long borne the nickname City of Rams (羊城) or City of the Five Rams (五羊城) from the five stones at the old Temple of the Five Immortals said to have been the sheep or goats ridden by the Taoist culture heroes credited with introducing rice cultivation to the area around the time of the city's foundation.[37] The former name "City of the Immortals" (仙城/五仙城) came from the same story. The more recent City of Flowers (花城) is usually taken as a simple reference to the area's fine greenery.

The English name "Canton" derived from Portuguese Cidade de Cantão,[38] a blend of dialectal pronunciations of "Guangdong"[39][40] (e.g., Cantonese Gwong2-dung1). Although it originally and chiefly applied to the walled city, it was occasionally conflated with Guangdong by some authors. It was adopted as the Postal Map Romanization of Guangzhou, and remained the official name until its name change to "Guangzhou". As an adjective, it is still used in describing the people, language, cuisine and culture of Guangzhou and the surrounding Liangguang region. The 19th-century name was "Kwang-chow foo".[41]

History

editPrehistory

editA settlement now known as Nanwucheng was present in the area by 1100 BC.[42][43] Some traditional Chinese histories placed Nanwucheng's founding during the reign of King Nan of Zhou,[44][45] emperor of Zhou from 314 to 256 BC. It was said to have consisted of little more than a stockade of bamboo and mud.[44][45]

Nanyue

editGuangzhou, then known as Panyu, was founded on the eastern bank of the Pearl River in 214 BC.[41] Ships commanded by tradespersons arrived on the South China coast in the late antiquity. Surviving records from the Tang dynasty confirm, that the residents of Panyu observed a range of trade missions. Records on foreign trade ships reach upon til the late 20th century.[46]

Panyu was the seat of Qin Empire's Nanhai Commandery, and served as a base for the first invasion of the Baiyue lands in southern China. Legendary accounts claimed that the soldiers at Panyu were so vigilant that they did not remove their armor for three years.[47] Upon the fall of the Qin, General Zhao Tuo established the kingdom of Nanyue and made Panyu its capital in 204 BC. It remained independent throughout the Chu-Han Contention, although Zhao negotiated recognition of his independence in exchange for his nominal submission to the Han in 196 BC.[48] Archeological evidence shows that Panyu was an expansive commercial center: in addition to items from central China, archeologists have found remains originating from Southeast Asia, India, and even Africa.[49] Zhao Tuo was succeeded by Zhao Mo and then Zhao Yingqi. Upon Zhao Yingqi's death in 115 BC, his younger son Zhao Xing was named as his successor in violation of Chinese primogeniture. By 113 BC, his Chinese mother, the Empress Dowager Jiu (樛) had prevailed upon him to submit Nanyue as a formal part of the Han Empire. The native prime minister Lü Jia (呂嘉) launched a coup, killing Han ambassadors along with the king, his mother, and their supporters.[50] A successful ambush then annihilated a Han force which had been sent to arrest him. Emperor Wu of Han took offense and launched a massive riverine and seaborne war: six armies under Lu Bode and Yang Pu[51] took Panyu and annexed Nanyue by the end of 111 BC.[50]

Imperial China

editIncorporated into the Han dynasty, Panyu became a provincial capital. In AD 226, it became the seat of Guang Prefecture, which gave it its modern name. The Old Book of Tang described Guangzhou as an important port in southern China.[52] Direct routes connected the Middle East and China, as shown in the records of a Chinese prisoner returning home from Iraq twelve years after his capture at Talas.[53] Relations were often strained: while China was undergoing the An Lushan Rebellion, Arab and Persian pirates[54] sacked the city on 30 October 758[55][56][57][58] and in revenge thousands of Arabs and Persians were killed by Chinese rebels in the Yangzhou massacre (760). In the Guangzhou massacre about 200,000 Arab, Persian and other foreigners were killed by Chinese rebel Huang Chao in 878, along with the city's Jews, Christians,[59][60][61] and Parsis.[62][63] The port was closed for fifty years after its destruction.[54]

Amid the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms that followed the collapse of the Tang dynasty, the Later Liang governor Liu Yan used his base at Panyu to establish a "Great Yue" or "Southern Han" empire, which lasted from 917 to 971. The region enjoyed considerable cultural and economic success in this period. From the 10th to 12th century, there are records that the large foreign communities were not exclusively men, but included "Persian females".[64][65] According to Odoric of Pordenone, Guangzhou was as large as three Venices in terms of area, and rivaled all of Italy in the amount of crafts produced. He also noted the large amount of ginger available as well as large geese and snakes.[66] Guangzhou was visited by the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta during his journey around the world in the 14th century.[67] He detailed the process by which the Chinese constructed their large ships in the port's shipyards.[68]

Shortly after the Hongwu Emperor's declaration of the Ming dynasty, he reversed his earlier support of foreign trade and imposed the first of a series of sea bans (海禁).[69] These banned private foreign trade upon penalty of death for the merchant and exile for his family and neighbors.[70] Previous maritime intendancies of Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and Ningbo were closed in 1384[71] and legal trade became limited to the tribute delegations sent to or by official representatives of foreign governments.[72]

Following the Portuguese conquest of the Melaka Sultanate, Rafael Perestrello traveled to Guangzhou as a passenger on a native junk in 1516.[73] His report induced Fernão Pires de Andrade to sail to the city with eight ships the next year,[73] but De Andrade's exploration[74] was understood as spying[75] and his brother Simão and others began attempting to monopolize trade,[76] enslaving Chinese women[77] and children, engaging in piracy,[78] and fortifying the island of Tamão.[79][80] Rumors even circulated that Portuguese were eating the children.[81][82] The Guangzhou administration was charged with driving them off:[78] they bested the Portuguese at the Battle of Tunmen[83] and in Xicao Bay; held a diplomatic mission hostage in a failed attempt to pressure the restoration of the sultan of Malacca,[84] who had been accounted a Ming vassal;[85] and, after placing them in cangues and keeping them for most of a year, ultimately executed 23 by lingchi.[86] With the help of local pirates,[81] the "Folangji" then carried out smuggling at Macao, Lampacau, and St John's Island (now Shangchuan),[77] until Leonel de Sousa legalized their trade with bribes to Admiral Wang Bo (汪柏) and the 1554 Luso-Chinese Accord. The Portuguese undertook not to raise fortifications and to pay customs dues;[87] three years later, after providing the Chinese with assistance suppressing their former pirate allies,[88] the Portuguese were permitted to warehouse their goods at Macau instead of Guangzhou itself.[89]

In October 1646, the Longwu Emperor's brother, Zhu Yuyue fled by sea to Guangzhou, the last stronghold of the Ming empire. On December 11, he declared himself the Shaowu Emperor, borrowing his imperial regalia from local theater troupes.[91] He led a successful offense against his cousin Zhu Youlang but was deposed and executed on January 20, 1647, when the Ming turncoat Li Chengdong (李成棟) sacked the city on behalf of the Qing.[92]

The Qing became somewhat more receptive to foreign trade after gaining control of Taiwan in 1683.[93] The Portuguese from Macau and Spaniards from Manila returned, as did private Muslim, Armenian, and English traders.[94] From 1699 to 1714, the French and British East India Companies sent a ship or two each year;[94] the Austrian Ostend General India Co. arrived in 1717,[95] the Dutch East India Co. in 1729,[96] the Danish Asiatic Co. in 1731, and the Swedish East India Co. the next year.[94] These were joined by the occasional Prussian or Trieste Company vessel. The first independent American ship arrived in 1784, and the first colonial Australian one in 1788.[citation needed] By that time, Guangzhou was one of the world's greatest ports, organized under the Canton System.[97] The main exports were tea and porcelain.[94] As a meeting place of merchants from all over the world, Guangzhou became a major contributor to the rise of the modern global economy.[98] Guangzhou is the site of the Thirteen Factories, which were the only legal place to conduct foreign trade with China from 1757 to 1842.[99]: xviii

In the 19th century, most of the city's buildings were still only one or two stories. However, there were notable exceptions such as the Flower Pagoda of the Temple of the Six Banyan Trees, and the guard tower known as the Five-Story Pagoda. The subsequently urbanized northern hills were bare and covered with traditional graves. The brick city walls were about 6 mi (10 km) in circumference, 25 ft (8 m) high, and 20 ft (6 m) wide. Its eight main gates and two water gates all held guards during the day and were closed at night. The wall rose to incorporate a hill on its northern side and was surrounded on the other three by a moat which, along with the canals, functioned as the city's sewer, emptied daily by the river's tides. A partition wall with four gates divided the northern "old town" from the southern "new town" closer to the river; the suburb of Xiguan (Saikwan; "West Gate") stretched beyond and the boats of fishers, traders, and Tanka ("boat people") almost entirely concealed the riverbank for about 4 mi (6 km). It was common for homes to have a storefront facing the street and to treat their courtyards as a kind of warehouse.[41] The city was part of a network of signal towers so effective that messages could be relayed to Beijing—about 1,200 mi (1,931 km) away—in less than 24 hours.[100]

The Canton System was maintained until the outbreak of the First Opium War in 1839. Following a series of battles in the Pearl River Delta, the British captured Canton on March 18, 1841.[101] The Second Battle of Canton was fought two months later.[102] Following the Qing's 1842 treaty with Great Britain, Guangzhou lost its privileged trade status as more and more treaty ports were opened to more and more countries, usually including extraterritorial enclaves. Amid the decline of Qing prestige and the chaos of the Red Turban Rebellion (1854–1856), the Punti and Hakka waged a series of clan wars from 1855 to 1867 in which one million people died. The foreign trade facilities were destroyed by local Chinese in the Arrow War (1856–1858). The international community relocated to the outskirts and most international trade moved through Shanghai.[103][104]

The concession for the Guangdong–Hankou Railway was awarded to the American China Development Co. in 1898. It completed its branch line west to Foshan and Sanshui before being engulfed in a diplomatic crisis after a Belgian consortium bought a controlling interest and the Qing subsequently canceled its concession. J.P. Morgan was awarded millions in damages[105] and the line to Wuchang was not completed until 1936[106] and the completion of a unified Beijing–Guangzhou Railway waited until the completion of Wuhan's Yangtze River Bridge in 1957.

Modern China

editRevolutions

editDuring the late Qing dynasty, Guangzhou was the site of revolutionary attempts such as the Uprisings of 1895 and 1911 that were the predecessors of the successful Xinhai Revolution, which overthrew the Qing dynasty. The 72 revolutionaries whose bodies were found after the latter uprising are honored as the city's 72 Martyrs at the Huanghuagang ("Yellow Flower Mound") Mausoleum.

Republic of China

editAfter the assassination of Song Jiaoren and Yuan Shikai's attempts to remove the Nationalist Party of China from power, the leader of Guangdong Hu Hanmin joined the 1913 Second Revolution against him[107] but was forced to flee to Japan with Sun Yat-sen after its failure. The city came under national spotlight again in 1917, when Prime Minister Duan Qirui's abrogation of the constitution triggered the Constitutional Protection Movement. Sun Yat-sen came to head the Guangzhou Military Government supported by the members of the dissolved parliament and the Southwestern warlords. The Guangzhou government fell apart as the warlords withdrew their support. Sun fled to Shanghai in November 1918 until the Guangdong warlord Chen Jiongming restored him in October 1920 during the Yuegui Wars.[108] On June 16, 1922, Sun was ousted in a coup and fled on the warship Yongfeng after Chen sided with the Zhili Clique's Beijing government. In the following months Sun mounted a counterattack into Guangdong by rallying supporters from Yunnan and Guangxi, and in January established a government in the city for the third time.

From 1923 to 1926, Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang (KMT) used the city as a base to prosecute a renewed revolution in China by conquering the warlords in the north. Although Sun was previously dependent on opportunistic warlords who hosted him in the city, with the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek, the KMT developed its own military power to serve its ambition. The Canton years saw the evolution of the KMT into a revolutionary movement with a strong military focus and ideological commitment, setting the tone of the KMT rule of China beyond 1927.

In 1924, the KMT made the momentous decision to ally with the Communist Party and the USSR. With Soviet help, KMT reorganized itself along the Leninist line and adopted a pro-labor and pro-peasant stance. The Kuomintang-CCP cooperation was confirmed in the First Congress of the KMT and the communists were instructed to join the KMT. The allied government set up the Peasant Movement Training Institute in the city, of which Mao Zedong was a director for one term. Sun and his military commander Chiang used Soviet funds and weapons to build an armed force staffed by communist commissars, training its cadres in the Whampoa Military Academy.[108] In August, the fledgling army suppressed the Canton Merchants' Corps Uprising. The next year the anti-imperialist May Thirtieth Movement swept the country, and the KMT government called for strikes in Canton and Hong Kong. The tensions of the massive strikes and protests led to the Shakee Massacre.

After the death of Sun Yat-sen in 1925 the mood was changing in the party toward the communists. In August the left-wing KMT leader Liao Zhongkai was assassinated and the right-wing leader Hu Hanmin, the suspected mastermind, was exiled to the Soviet Union, leaving the pro-communist Wang Jingwei in charge. Opposing communist encroachment, the right-wing Western Hills Group vowed to expel the communists from the KMT. The "Canton Coup" on March 20, 1926, saw Chiang solidify his control over the Nationalists and their army against Wang Jingwei, the party's left wing, its Communist allies, and its Soviet advisors.[109][110] By May, he had ended civilian control of the military[110] and begun his Northern Expedition against the warlords of the north. Its success led to the split of the KMT between Wuhan and Nanking and the purge of the communists in the April 12 Incident. Immediately afterwards Canton joined the purge under the auspice of Li Jishen, resulting in the arrest of communists and the suspension of left wing KMT apparatuses and labor groups. Later in 1927 when Zhang Fakui, a general supportive of the Wuhan faction, seized Canton and installed Wang Jingwei's faction in the city, the communists saw an opening and launched the Guangzhou Uprising. Prominent communist military leaders Ye Ting and Ye Jianying led the failed defense of the city. Soon, control of the city reverted to Li Jishen.

Li Jishen was deposed during a war between Chiang and the New Guangxi Clique. By 1929, Chen Jitang had established himself as the powerholder of Guangdong. In 1931 he threw his weight behind the anti-Chiang schism by hosting a separate Nationalist government in Guangzhou.[111] The opposition to Chiang included KMT leaders like Wang Jingwei, Sun Fo and others from diverse factions. The peace negotiations amid the armed standoff led to the 4th National Congress of Kuomintang being held separately by three factions in Nanjing, Shanghai, and Canton. Resigning all his posts, Chiang pulled off a political compromise that reunited all factions. While the intraparty division was resolved, Chen kept his power until he was defeated by Chiang in 1936. During the WW2, the "Canton Operation" subjected the city to Japanese occupation by the end of December 1938.

People's Republic of China

editAmid the closing months before total Communist victory, Guangzhou briefly served as the capital of the Republican government. Guangzhou was captured on October 14, 1949. Amid a massive exodus to Hong Kong and Macau, defeated Nationalist forces blew up the Haizhu Bridge across the Pearl River in retreat. The Cultural Revolution had a large effect on the city, with many of its temples, churches and other monuments destroyed during this chaotic period.

The People's Republic of China initiated building projects including new housing on the banks of the Pearl River to adjust the city's boat people to life on land. Since the 1980s, the city's close proximity to Hong Kong and Shenzhen and its ties to overseas Chinese made it one of the first beneficiaries of China's opening up under Deng Xiaoping. Beneficial tax reforms in the 1990s also helped the city's industrialization and economic development.

The municipality was expanded in the year 2000, with Huadu and Panyu joining the city as urban districts and Conghua and Zengcheng as more rural counties. The former districts of Dongshan and Fangcun were abolished in 2005, merged into Yuexiu and Liwan respectively. The city acquired Nansha and Luogang. The former was carved out of Panyu, the latter from parts of Baiyun, Tianhe, Zengcheng, and an exclave within Huangpu. The National People's Congress approved a development plan for the Pearl River Delta in January 2009; on March 19 of the same year, the Guangzhou and Foshan municipal governments agreed to establish a framework to merge the two cities.[112] In 2014, Luogang merged into Huangpu and both Conghua and Zengcheng counties were upgraded to districts.

On 16 June 2022 an EF2 tornado struck the city, causing major power outages and knocking out power to the city's subway lines.[113][114][115]

-

The Thirteen Factories c. 1805, displaying the flags of Denmark, Spain, the United States, Sweden, Britain, and the Netherlands

-

An 1855 painting of the gallery of Tingqua, one of the most successful suppliers of "export paintings" for Guangzhou's foreign traders.

-

The Flowery Pagoda at the Temple of the Six Banyan Trees in 1863

-

The Guangzhou Bund in 1930, with rows of Tanka boats

-

A short film of Guangzhou in 1937

-

The People's Liberation Army entering Guangzhou on 14 October 1949

Geography

editThe old town of Guangzhou was near Baiyun Mountain on the east bank of the Pearl River (Zhujiang) about 80 mi (129 km) from its junction with the South China Sea and about 300 mi (483 km) below its head of navigation.[41] It commanded the rich alluvial plain of the Pearl River Delta, with its connection to the sea protected at the Humen Strait.[41] The present city spans 7,434.4 km2 (2,870.4 sq mi) on both sides of the river from 112° 57′ to 114° 03′ E longitude and 22° 26′ to 23° 56′ N latitude in south-central Guangdong. The Pearl is the 4th-largest river of China.[117] Intertidal ecosystems exist on the tidal flat lining the river estuary, however, many of the tidal flats have been reclaimed for agriculture.[118] Baiyun Mountain is now locally referred to as the city's "lung" (市肺).[10][119][why?]

The elevation of the prefecture generally increases from southwest to northeast, with mountains forming the backbone of the city and the ocean comprising the front. Tiantang Peak is the highest point of elevation at 1,210 m (3,970 ft) above sea level.

Natural resources

editThere are 47 different types of minerals and also 820 ore fields in Guangzhou, including 18 large and medium-sized oil deposits. The major minerals are granite, cement limestone, ceramic clay, potassium, albite, salt mine, mirabilite, nepheline, syenite, fluorite, marble, mineral water, and geothermal mineral water. Since Guangzhou is located in the water-rich area of southern China, it has a wide water area with many rivers and water systems, accounting for 10% of the total land area. The rivers and streams improve the landscape and keep the ecological environment of the city stable.[120]

Water resources

editThe main characteristics of Guangzhou's water resources are that there are relatively few local water resources and relatively abundant transit water resources. The city's water area is 74,400 hectares, accounting for 10.05% of the city's land area. The main rivers include Beijiang, Dongjiang North Mainstream, Zengjiang, Liuxi River, Baini River, Pearl River Guangzhou Reach, Shiqiao Waterway, and Shawan Waterway. Beijiang, The Dongjiang River flows through Guangzhou City and merges with the Pearl River to flow into the sea. The local average total water resources is 7.979 billion cubic meters, including 7.881 billion cubic meters of surface water and 1.487 billion cubic meters of groundwater. Calculated based on the amount of local water resources and the permanent population counted in the sixth census in 2010, there are 1.0601 million cubic meters of water resources per square kilometer, with an average of 628 cubic meters per capita, which is one-half of the country's per capita water resources. The amount of water resources for transit passengers is 186.024 billion cubic meters, which is 23 times the total local water resources. The passenger water resources are mainly concentrated in the southern Wanghe District and Zengcheng District. The passenger water resources diverted from the Xijiang and Beijiang Rivers into Guangzhou City are 159.15 billion cubic meters, and the passenger water resources diverted from the Dongjiang River into the north mainstream of the Dongjiang River are 14.203 billion cubic meters. meters and the water inflow from the upper reaches of the Zengjiang River is 2.828 billion cubic meters. The southern river network area is in the tidal influence area, with large runoff and a strong tidal effect. The three major entrances of the Pearl River, Humen, Jiaomen, and Hongqili, enter the Lingding Ocean and exit the South China Sea in the south of Guangzhou City. The annual high tide volume is 271 billion cubic meters and the annual ebb tide volume is 408.8 billion cubic meters. The annual runoff of the three major entrances is 137.7 billion cubic meters. Compared with meters, the annual tide can bring a large amount of water, part of which is freshwater resources that can be utilized.[121]

Biological Resources

editCultivated crops in Guangzhou have the distinctive characteristics of the transition from the tropics to the subtropics, and it is one of the richest regions in China in terms of fruit tree resources, including three major categories of tropical, subtropical, and temperate zones, 41 families, 82 genera and 174 species, totaling more than 500 varieties (among which there are 55 major varieties of lychee). It is the center of origin and variety of lychee, longan, yellow skin, black (white) olive, and so on. Vegetables are known for their high quality and variety, with 15 major categories, 127 species, and more than 370 varieties. Flowers include fresh cut flowers (fresh cut flowers, fresh cut leaves, fresh cut branches), potted plants (potted flowers, bonsai, flower bed plants), ornamental seedlings, edible and medicinal flowers, industrial and other uses of flowers, lawns, seedlings, etc. More than 3,000 traditional varieties and in recent years the introduction of new varieties, development, and utilization. Grain, cash crops, livestock, poultry, aquatic products, wild animals, and a wide variety of famous and excellent varieties, including Zengcheng Simiao rice is the first protected variety in Guangzhou City to obtain geographical indications.[122]

Mineral Resources

editThe geological structure of Guangzhou City is quite complex, with good conditions for mineralization. Forty-seven kinds of minerals (including subspecies) have been discovered, with 820 mineral sites and 25 large and medium-sized mining areas. The main minerals are granite for construction, limestone for cement, ceramic clay, potassium, sodium feldspar, salt mines, manganese, nepheline orthoclase, fluorite, marble, mineral water, and thermal mineral water. Energy minerals and non-ferrous minerals in the area are in short supply, sporadically distributed, small in scale, and unstable in grade.[122] ,

Climate

editDespite being located just south of the Tropic of Cancer, Guangzhou has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa) influenced by the East Asian monsoon. Summers are wet with high temperatures, high humidity, and a high heat index. Winters are mild and comparatively dry. Guangzhou has a lengthy monsoon season, spanning from April through September. Monthly averages range from 13.8 °C (56.8 °F) in January to 28.9 °C (84.0 °F) in July, while the annual mean is 22.4 °C (72.3 °F).[10] Autumn, from October to December, is very moderate, cool and windy, and is the best travel time.[123] The relative humidity is approximately 76 percent, whereas annual rainfall in the metropolitan area is over 1,950 mm (77 in).[10] With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 17 percent in March to 51 percent in October, the city receives 1,559 hours of bright sunshine annually, considerably less than nearby Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Extreme temperatures since 1951 have ranged from 0 °C (32 °F) on 11 February 1957 and 23 December 1999[124] to 39.1 °C (102.4 °F) on 1 July 2004,[125] though an unofficial record low of −5.0 °C (23.0 °F), in which modern meteorologists believe it to be −3.0 °C (26.6 °F) was recorded on 18 January 1893 and for the station that begun records in 1912 located in Huangpu District, an unofficial record low of −0.3 °C (31.5 °F) was recorded on 8 December 1934.[126][127][128] The last recorded snowfall in the city was on January 24, 2016, 87 years after the second last recorded snowfall.[129]

| Climate data for Guangzhou (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1934–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.4 (83.1) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

33.5 (92.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

38.9 (102.0) |

39.1 (102.4) |

38.3 (100.9) |

37.6 (99.7) |

36.2 (97.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

39.1 (102.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.7 (65.7) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

26.9 (80.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.8 (56.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.4 (81.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.2 (68.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.2 (75.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.7 (45.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51.1 (2.01) |

56.1 (2.21) |

101.0 (3.98) |

193.8 (7.63) |

329.0 (12.95) |

364.9 (14.37) |

242.6 (9.55) |

270.3 (10.64) |

203.2 (8.00) |

67.3 (2.65) |

37.4 (1.47) |

33.4 (1.31) |

1,950.1 (76.77) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 7.2 | 9.4 | 13.8 | 15.3 | 17.4 | 19.4 | 17.0 | 16.8 | 12.0 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 145.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 76 | 80 | 82 | 81 | 82 | 79 | 80 | 77 | 70 | 69 | 67 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 112.9 | 77.5 | 61.6 | 69.1 | 103.4 | 127.5 | 179.0 | 166.4 | 167.0 | 182.2 | 159.7 | 152.7 | 1,559 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 33 | 24 | 17 | 18 | 25 | 32 | 43 | 42 | 46 | 51 | 49 | 46 | 36 |

| Source: China Meteorological Data Service Center [130][131][132] all-time extreme temperature[126]Hong Kong Observatory[133] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

editGuangzhou is a sub-provincial city. It has direct jurisdiction over eleven districts:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economy

editGuangzhou is the main manufacturing hub of the Pearl River Delta, one of mainland China's leading commercial and manufacturing regions. In 2021, its GDP reached ¥2,823 billion (US$444.37 billion in nominal), making it the 2nd largest economy in the South-Central China region after Shenzhen.[138] Guangzhou's GDP (nominal) was $444.37 billion in 2021, exceeding that [139] Guangzhou's per capita was ¥151,162 ($23,794 in nominal).[138] Guangzhou is considered one of the most prosperous cities in China. Guangzhou ranks 10th in the world and 5th in China (after Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Shenzhen) in terms of the number of billionaires according to the Hurun Global Rich List 2020.[25] Guangzhou is projected to be among the world top 10 largest cities in terms of nominal GDP in 2035 (together with Shanghai, Beijing and Shenzhen in China) according to a study by Oxford Economics,[140] and its nominal GDP per capita will reach above $42,000 in 2030.[141] Guangzhou also ranks 21st globally (between Washington, D.C., and Amsterdam) and 8th in the whole Asia & Oceania region (behind Shanghai, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Singapore, Beijing, Shenzhen and Dubai) in the 2020 Global Financial Centers Index (GFCI).[22] Owing to rapid industrialization, it was once also considered a rather polluted city. After green urban planning was implemented, it is now one of the most livable cities in China.

Zhujiang New Town

editZhujiang New Town is the central business district of Guangzhou in the 21st century. It covers 6.44 km2 in Tianhe District. Multiple financial institutions are headquartered in this area.

-

Zhujiang New Town

-

Skyscrapers in Zhujiang New Town

-

Skyscrapers in Zhujiang New Town

-

Haixin Bridge and Canton Tower near Zhujiang New Town

-

Zhujiang New Town at night

Canton Fair

editThe Canton Fair, formally the "China Import and Export Fair", is held every year in April and October by the Ministry of Trade. Inaugurated in the spring of 1957, the fair is a major event for the city. It is the trade fair with the longest history, highest level, and largest scale in China.[142] From the 104th session onwards, the fair moved to the new Guangzhou International Convention and Exhibition Center (广州国际会展中心) in Pazhou, from the older complex in Liuhua. The GICEC is served by two stations on Line 8 and three stations on Tram Line THZ1. Since the 104th session, the Canton Fair has been arranged in three phases instead of two phases.

-

The former Canton Fair site at Yuexiu's Liuhua Complex

-

The new Canton Fair Complex

-

Interior of the Canton Fair Complex

Local products

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

- Cantonese cuisine is one of China's most famous and popular regional cuisines, with a saying stating simply to "Eat in Guangzhou" (食在廣州).

- Cantonese sculpture includes work in jade, wood, and (controversially) ivory.

- Canton porcelain developed over the past three centuries as one of the major forms of exportware. It is now known within China for its highly colorful style.

- Cantonese embroidery is one of china's four main styles of the embroidery.

- Zhujiang Beer, a pale lager, is one of China's most successful brands.

Industry

edit- GAC Group

- Guangzhou Economic and Technological Development Zone

- Guangzhou Nansha Export Processing Zone

- The Export Processing Zone was founded in 2005. Its total planned area is 1.36 km2 (0.53 sq mi).[143] It is located in Nansha District and it belongs to the provincial capital, Guangzhou. The major industries encouraged in the zone include automobile assembly, biotechnology and heavy industry. It is situated 54 km (34 mi) (a 70 minutes drive) south of Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport and close to Nansha Port. It also has the advantage of Guangzhou Metro line 4 which is being extended to Nansha Ferry Terminal.

- Guangzhou Free Trade Zone

- The zone was founded in 1992. It is located in the east of Huangpu District and near to Guangzhou Economic and Technological Development Zone. It is also very close to Guangzhou Baiyun Airport.[144] The major industries encouraged in the zone include international trade, logistics, processing and computer software. Recently the Area has been rebranded and is now being marketed under the name Huangpu District. Next to the industries above, new sectors are being introduced to the business environment, including new energy, AI, new mobility, new materials, information and communication technology and new transport. It is also home to the Guangzhou IP Court.[145]

- Guangzhou Science City

Business Environment

editGuangzhou is a hub for international businesses. According to an article by China Briefing, over 30,000 foreign-invested companies had settled in Guangzhou by 2018, including 297 Fortune Global 500 companies with projects and 120 Fortune Global 500 companies with headquarters or regional headquarters in the city.[146]

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950[147] | 2,567,645 | — |

| 1960[147] | 3,683,104 | +43.4% |

| 1970[147] | 4,185,363 | +13.6% |

| 1980[147] | 5,018,638 | +19.9% |

| 1990[147] | 5,942,534 | +18.4% |

| 2000[147] | 9,943,000 | +67.3% |

| 2002[148] | 10,106,229 | +1.6% |

| 2005[149] | 9,496,800 | −6.0% |

| 2006[149] | 9,966,600 | +4.9% |

| 2007[149] | 10,530,100 | +5.7% |

| 2008[149] | 11,153,400 | +5.9% |

| 2009[149] | 11,869,700 | +6.4% |

| 2010[147] | 12,701,948 | +7.0% |

| 2011[150] | 12,751,400 | +0.4% |

| 2012[150] | 12,832,900 | +0.6% |

| 2013[150] | 12,926,800 | +0.7% |

| 2014[150] | 13,080,500 | +1.2% |

| 2018 | 14,904,400 | +13.9% |

| Population size may be affected by changes to administrative divisions. | ||

The 2010 census found Guangzhou's population to be 12.78 million. As of 2014[update], it was estimated at 13,080,500,[151][150] with 11,264,800 urban residents.[152] Its population density is thus around 1,800 people per km2. The built-up area of the Guangzhou proper connects directly to several other cities. The built-up area of the Pearl River Delta Economic Zone covers around 17,573 km2 (6,785 sq mi) and has been estimated to house 22 million people, including Guangzhou's nine urban districts, Shenzhen (5.36m), Dongguan (3.22m), Zhongshan (3.12m), most of Foshan (2.2m), Jiangmen (1.82m), Zhuhai (890k), and Huizhou's Huiyang District (760k).[citation needed] The total population of this agglomeration is over 28 million after including the population of the adjacent Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.[citation needed] The area's fast-growing economy and high demand for labor has produced a huge "floating population" of migrant workers; thus, up to 10 million migrants reside in the area least six months each year.[citation needed] In 2008, about five million of Guangzhou's permanent residents were hukouless migrants.[153]

Ethnicity and language

editMost of Guangzhou's population is Han Chinese. Almost all Cantonese people speak Cantonese as their first language,[155] while most migrants speak forms of Mandarin.[153] In 2010, each language was the native tongue of roughly half of the city's population,[156] although minor but substantial numbers speak other varieties as well.[citation needed] In 2018, He Huifeng of the South China Morning Post stated that younger residents have increasingly favored using Mandarin instead of Cantonese in their daily lives, causing their Cantonese-speaking grandparents and parents to use Mandarin to communicate with them. He Huifeng stated that factors included local authorities discouraging the use of Cantonese in schools and the rise in prestige of Mandarin-speaking Shenzhen.[157] Jinan University released a survey result of the Guangzhou youths born in the year 2000 or after that were part of this educational study showed that 69% could still speak and understand Cantonese, 20% can understand Cantonese, but unable to speak it, and 11% completely had no knowledge of Cantonese. Jinan University's study of these Guangzhou youths also indicated when it came to the daily recreational use of Cantonese, roughly 40%-50% of them participated in these recreational functions with the usage of Cantonese with 51.4% of them in mobile games, 47% in Social Platforms, 44.1% in TV shows, and 39.8% in Books and Newspapers. Despite some decline in the use of Cantonese, it is faring better in survival, popularity, and prestige than other Chinese languages due to the historical pride in the language and culture, as well as the wide popularity and availability of mainstream Cantonese entertainment, which encourages locals to retain the Cantonese language.[158][159] As of the 2020s, additional renewed efforts were introduced to preserve the local Cantonese language and culture with some limited Cantonese language classes now being taught in some schools as well as hosting Cantonese appreciation cultural events along with hosting activities that cater to the local Cantonese culture and language as well as many local Cantonese speaking families are now placing much stronger emphasis on their children to speak Cantonese to preserve the culture and language. In a 2018 report study by Shan Yunming and Li Sheng, the report showed that 90% of people living in Guangzhou are bilingual in both Cantonese and Mandarin, though fluency will vary depending on if they are locally born to the city and the surrounding Guangdong province or migrants from other provinces, which shows how much importance the Cantonese language still has in the city despite the strict policy rules from the government to be using Mandarin as the country's official language.[160][161] Guangzhou has an even more unbalanced gender ratio than the rest of the country. While most areas of China have 112–120 boys per 100 girls, the Guangdong province that houses Guangzhou has more than 130 boys for every 100 girls.[162][163][164]

Guangzhou also possesses a large resident population who are Hakka people. There are seven administrative districts in Guangzhou with a considerable Hakka population: Zengcheng District, Huadu District, Conghua District, Baiyun District, Tianhe District, Yuexiu District and Panyu District. It is estimated that in Zengcheng district and Huadu district of Guangzhou, Hakka speakers account for about 40 percent and a third of the district's population.[165][166]

Recent years have seen a huge influx of migrants, with up to 30 million additional migrants living in the Guangzhou area for at least six months out of every year with the majority being female migrants and many becoming local Guangzhou people. This huge influx of people from other areas, called the floating population, is due to the city's fast-growing economy and high labor demands. Guangzhou Mayor Wan Qingliang told an urban planning seminar that Guangzhou is facing a very serious population problem stating that, while the city had 10.33 million registered residents at the time with targets and scales of land use based on this number, the city actually had a population with migrants of nearly 15 million. According to the Guangzhou Academy of Social Sciences researcher Peng Peng, the city is almost at its maximum capacity of just 15 million, which means the city is facing a great strain, mostly due to a high population of unregistered people.[162]

According to the 2000 National Census, marriage is one of the top two reasons for permanent migration and is particularly important for women as 29.3% of the permanent female migrants migrate for marriage [Liang et al.,2004]. Many of the female economic migrants marry men from Guangzhou in hopes of a better life.[167] but like elsewhere in the People's Republic of China, the household registration system (hukou) limits migrants' access to residences, educational institutions and other public benefits. It has been noted that many women end up in prostitution.[168] In May 2014, legally employed migrants in Guangzhou were permitted to receive a hukou card allowing them to marry and obtain permission for their pregnancies in the city, rather than having to return to their official hometowns as previously.[169]

Historically, the Cantonese people have made up a sizable part of the 19th- and 20th-century Chinese diaspora; in fact, many overseas Chinese have ties to Guangzhou. This is particularly true in the United States,[170] Canada,[171] and Australia.

Demographically, the only significant immigration into China has been by overseas Chinese, but Guangzhou sees many foreign tourists, workers, and residents from the usual locations such as the United States. Notably, it is also home to thousands of African immigrants, including people from Nigeria, Somalia, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo.[172]

Metropolitan area

editThe encompassing metropolitan area was estimated by the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) to have, as of 2010[update], a population of 25 million.[173][174]

Development of Guangzhou

editGong et al. 2018 report on the development of Guangzhou from 1990 until 2020, showing how in 1990, the developed residential districts were almost exclusively concentrated in a small part of western Guangzhou whereas other parts of Guangzhou had a smaller limited amount of developed residential communities being overwhelmingly surrounded by agricultural and forest lands. However, from 2005 until 2020, other parts of the city eventually began to develop more so residential communities and in the 2020 map report, it showed fully developed residential communities going from west to east of the city whereas the very southern part and large portions of northern Guangzhou still remain mainly agricultural and forest lands with very limited developed residential communities.[175][176]

Transportation

editUrban mass transit

editWhen the first line of the Guangzhou Metro opened in 1997, Guangzhou was the fourth city in Mainland China to have an underground railway system, behind Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai. Currently the metro network is made up of sixteen lines, covering a total length of 652.81 km (405.64 mi).[177] A long-term plan is to make the city's metro system expand to over 500 km (310 mi) by 2020 with 15 lines in operation. In addition to the metro system there is also the Haizhu Tram line which opened on December 31, 2014.[178]

The Guangzhou Bus Rapid Transit (GBRT) system which was introduced in 2010 along Zhongshan Road. It has several connections to the metro and is the world's 2nd-largest bus rapid transit system with 1,000,000 passenger trips daily.[179] It handles 26,900 pphpd during the peak hour a capacity second only to the TransMilenio BRT system in Bogota.[180] The system averages one bus every 10 seconds or 350 per hour in a single direction and contains the world's longest BRT stations—around 260 m (850 ft) including bridges.

Motor transport

editIn the 19th century, the city already had over 600 long, straight streets; these were mostly paved but still very narrow.[41] In June 1919, work began on demolishing the city wall to make way for wider streets and the development of tramways. The demolition took three years in total.[181]

In 2009, it was reported that all 9,424 buses and 17,695 taxis in Guangzhou would be operating on LPG-fuel by 2010 to promote clean energy for transport and improve the environment ahead of the 2010 Asian Games which were held in the city.[182] At present[when?], Guangzhou is the city that uses the most LPG-fueled vehicles in the world, and at the end of 2006, 6,500 buses and 16,000 taxis were using LPG, taking up 85 percent of all buses and taxis[183]

Effective January 1, 2007, the municipal government banned motorcycles in Guangdong's urban areas. Motorcycles found violating the ban are confiscated.[184] The Guangzhou traffic bureau claimed to have reported reduced traffic problems and accidents in the downtown area since the ban.[185]

Airports

editGuangzhou's main airport is the Baiyun International Airport in Baiyun District; it opened on August 5, 2004.[186] This airport is the second busiest airport in terms of traffic movements in China. It replaced the old Baiyun International Airport, which was very close to the city center but failed to meet the city's rapidly growing air traffic demand. The old Baiyun International Airport was in operation for 72 years. Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport now has three runways, with two more planned.[187] Terminal 2 opened on April 26, 2018.[188] Another airport located in Zengcheng District is under planning.[189]

Guangzhou is also served by Hong Kong International Airport; ticketed passengers can take ferries from the Lianhuashan Ferry Terminal and Nansha Ferry Port in Nansha District to the HKIA Skypier.[190] There are also coach bus services connecting Guangzhou with HKIA.[191]

Rail

editGuangzhou is the terminus of the Beijing–Guangzhou, Guangzhou–Shenzhen, Guangzhou–Maoming and Guangzhou–Meizhou–Shantou conventional speed railways. In late 2009, the Wuhan–Guangzhou high-speed railway started service, with multiple unit trains covering 980 km (608.94 mi) at a top speed of 320 km/h (199 mph). In December 2014, the Guiyang–Guangzhou high-speed railway and Nanning-Guangzhou railway began service with trains running at top speeds of 250 km/h (155 mph) and 200 km/h (124 mph), respectively.[192] The Guangdong Through Train departs from the Guangzhou East railway station and arrives at the Hung Hom station in Kowloon, Hong Kong. The route is approximately 182 km (113 mi) in length and the ride takes less than two hours. Frequent coach services are also provided with coaches departing every day from different locations (mostly major hotels) around the city. A number of regional railways radiating from Guangzhou started operating such as the Guangzhou–Zhuhai intercity railway and the Guangzhou-Foshan-Zhaoqing intercity railway.

Water transport

editThere are daily high-speed catamaran services between Nansha Ferry Terminal and Lianhua Shan Ferry Terminal in Guangzhou and the Hong Kong China Ferry Terminal, as well as between Nansha Ferry Terminal and Macau Ferry Pier in Hong Kong.

- Transport in Guangzhou

-

Trains used by the Guangzhou Metro

-

GBRT station

Culture

editGuangzhou's culture is mainly Cantonese culture, which is a subset of the larger "Southern" or the "Lingnan" culture, followed by Hakka culture.[193] Notable aspects of Cantonese cultural heritage include:

- Cantonese language, the local and prestige variant of Yue Chinese.

- Cantonese cuisine, one of China's eight major culinary traditions.[194][note 1]

- Cantonese opera, usually divided into martial and literary performances.

- Xiguan (Saikwan), the area west of the former walled city.

The Guangzhou Opera House & Symphony Orchestra also perform classical Western music and Chinese compositions in their style. Cantonese music is a traditional style of Chinese instrumental music, while Cantopop is the local form of pop music and rock-and-roll which developed from neighboring Hong Kong.

It is worth noting that Cantonese language, Cantonese cuisine and Cantonese opera are the shared culture of the whole Guangdong region, not just the important cultural components of Guangzhou city. With a population of diverse background, the culture of Guangzhou also includes other categories, such as Hakka culture and language.

In the Hakka people inhabited areas of Guangzhou, Hakka culture has been well developed and preserved, and in the long history, the integration of Canton culture and Hakka culture has derived new cultural characteristics. Zengcheng, Guangzhou is a district with a history of more than 1800 years, with the harmonious coexistence of Canton culture and Hakka culture, the derived food culture has not only the non-heritage food such as Zhengguo Wonton, Lanxi Rice Noodle, and Goose Soup, but also the special food such as Yuecun Dace Fish Skin, Paitan Roasted Chicken, and Shitan Whole Cattle Banquet.[196]

Religions

editBefore the postmodern era, Guangzhou had about 124 religious pavilions, halls, and temples.[41] Today, in addition to the Buddhist Association, Guangzhou also has a Taoist Association, a Jewish community,[197][198] as well as a history with Christianity, reintroduced to China by colonial powers.[clarification needed]

Taoism

editTaoism and Chinese folk religion are still represented at a few of the city's temples. Among the most important is the Temple of the Five Immortals, dedicated to the Five Immortals credited with introducing rice cultivation at the foundation of the city. The five rams they rode were supposed to have turned into stones upon their departure and gave the city several of its nicknames.[199] However, the temple has not been restored as a Taoist temple status yet. Other famous temples include the City God Temple of Guangzhou and Sanyuan Palace. During the Cultural Revolution, all Taoist temples and shrines were practically destroyed or damaged by the red guards. Only a handful of them like Sanyuan Palace were restored during the 1980s. Guangzhou, like most of southern China, is also notably observant and continues the practice of Chinese ancestral worship during major festive occasions like the Qing Ming Festival and Zhong Yuan Festival.

Buddhism

editBuddhism is the most prominent religion in Guangzhou.[200] The Zhizhi Temple was founded in AD 233 from the estate of a Wu official; it is said to comprise the residence of Zhao Jiande, the last of the Nanyue kings, and has been known as the Guangxiao Temple ("Temple of Bright Filial Piety") since the Ming dynasty. The Buddhist missionary monk, Bodhidharma is traditionally said to have visited Panyu during the Liu Song or Liang dynasty (5th or 6th century). Around AD 520, Emperor Wu of the Liang ordered the construction of the Baozhuangyan Temple and the Xilai Monastery to store the relics of Cambodian Buddhist saints which had been brought to the city and to house the monks beginning to assemble there. The Baozhuangyan is now known as the Temple of the Six Banyan Trees, after a famous poem composed by Su Shi after a visit during the Northern Song.[citation needed] The Xilai Monastery was renamed as the Hualin Temple ("Flowery Forest Temple") after its reconstruction during the Qing dynasty.

The temples were badly damaged by both the Republican campaign to "Promote Education with Temple Property" (廟產興學) and the PRC's Cultural Revolution but have been renovated since the opening up that began in the 1980s. The Ocean Banner Temple on Henan Island, once famous in the west as the only tourist spot in Guangzhou accessible to foreigners, has been reopened as the Hoi Tong Monastery.

Christianity

editNestorian Christians first arrived in China via the overland Silk Road, but suffered during Emperor Wuzong's 845 persecution and were essentially extinct by the year 1000.[201][specify] The Qing-era ban on foreigners limited missionaries until it was abolished following the First Opium War, although the Protestant Robert Morrison was able to perform some work through his service with the British factory. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Guangzhou is housed at Guangzhou's Sacred Heart Cathedral, known locally as the "Stone House". A Gothic Revival edifice which was built by hand from 1861 to 1888 under French direction, its original Latin and French stained-glass windows were destroyed during the wars and amid the Cultural Revolution; they have since been replaced by English ones. The Canton Christian College (1888) and Hackett Medical College for Women (1902) were both founded by missionaries, they were known in Chinese as Lingnan University and later incorporated into Sun Yat-sen University. Since the opening up of China in the 1980s, there has been renewed interest in Christianity, but Guangzhou maintains pressure on underground churches which avoid registration with government officials.[202] The Catholic archbishop Dominic Tang was imprisoned without trial for 22 years; however, his present successor is recognized by both the Vatican and China's Patriotic Church.

Islam

editGuangzhou has had ties with the Islamic world since the Tang dynasty.[203] Relations were often strained: Arab and Persian pirates sacked the city on October 30, 758; the port was subsequently closed for fifty years.[54][55][56][57][58] Their presence came to an end under the revenge of Chinese rebel Huang Chao in 878, along with that of the Jews, Christians,[59][60][61] and Parsis.[62][63] Nowadays, the city is home to halal restaurants.[204]

- Religious sites in Guangzhou

-

The Hall of the 500 Arhats at the Flowery Forest Temple (Hualin) in the 1870s

-

Guangzhou's City God Temple

-

The sacred pigs of the Ocean Banner Temple (Hoi Tong) in the 1830s

-

The Flower Pagoda at the Temple of the Six Banyan Trees (Liurong)

-

The Thousand Buddha Tower at the present-day Hoi Tong Monastery

-

Tianhe Church, built in 2017

Sports

editThe 11,468 seat Guangzhou Gymnasium was a 2019 FIBA Basketball World Cup venue.[205]

From November 12 to 27, 2010, Guangzhou hosted the 16th Asian Games. The same year, it hosted the first Asian Para Games from December 12 to 19. Combined, these were the major sporting events the city ever hosted.[206]

Guangzhou also hosted the following major sporting events:

- 1987 The 6th National Games of China

- 1991 The 1st FIFA Women's World Cup

- 2001 The 2001 National Games of China

- 2007 The 8th National Traditional Games of Ethnic Minorities of the People's Republic of China

- 2008 The 49th World Table Tennis Championships

- 2009 The 11th Sudirman Cup: the world badminton mixed team championships

Current professional sports clubs based in Guangzhou include:

In the 2010s, Guangzhou became a Chinese soccer powerhouse, having won eight national titles between 2011 and 2019. The team has also won the AFC Champions League in 2013 and 2015. The club has competed at the 2013 and 2015 FIFA Club World Cup, where it lost 3–0 in the semifinal stage to the 2012–13 UEFA Champions League winners FC Bayern Munich and the 2014–15 UEFA Champions League winners FC Barcelona, respectively.[207]

Restaurants

editIn the 1990s the local press prolifically published reviews of restaurants in Guangzhou. The local newspapers introduced lifestyle pages and relied on infotainment to encourage the purchase of a daily newspaper.[208][page needed]

Destinations

editEight Views

editThe Eight Views of Ram City are Guangzhou's eight most famous tourist attractions. They have varied over time since the Song dynasty, with some being named or demoted by emperors. The following modern list was chosen through public appraisal in 2011:[citation needed]

- "Towers Shining through the New Town"

- "The Pearl River Flowing and Shining": The Pearl River from Bai'etan to Pazhou

- "Cloudy Mountain Green and Tidy": Baiyun Mountain Scenic Area

- "Yuexiu's Grandeur": Yuexiu Hill and Park

- "The Ancient Academy's Lingering Fame": The Chen Clan Ancestral Hall and its folk art museum

- "Liwan's Wonderful Scenery": Liwan Lake

- "Science City, Splendid as Brocade"

- "Wetlands Singing at Night": Nansha Wetlands Park

Parks and gardens

edit- Baiyun Mountain

- Nansha Wetland Park

- People's Park

- South China Botanical Garden

- Yuexiu Park

- Guangdong Tree Park

- Dongshanhu Park (东山湖公园; 東山湖公園)

- Liuhuahu Park (流花湖公园; 流花湖公園)

- Liwanhu Park (荔湾湖公园; 荔灣湖公園)

- Luhu Park (麓湖公园; 麓湖公園)

- Martyrs' Park (广州起义烈士陵园; 廣州起義烈士陵園)

- Pearl River Park (珠江公园; 珠江公園)

- Yuntai Garden (云台花园; 雲臺花園)

- Shimen National Forest Park(石门国家森林公园; 石門國家森林公園)

- Haizhu Lake Park(海珠湖公园; 海珠湖公園)

Tourist attractions

editGuangzhou attracts more than 223 million visitors each year, and the total revenue of the tourism exceeded 400 billion in 2018.[210] There are many tourist attractions, including:

- Canton Tower

- Chen Clan Ancestral Hall, housing Guangzhou's folk art museum

- Chime-Long Paradise

- Chime-Long Waterpark (simplified Chinese: 长隆水上乐园; traditional Chinese: 長隆水上樂園)

- Guangdong Provincial Museum

- Guangzhou Zoo

- Mulberry Park, public center which demonstrates mulberry growing and silk making

- Museum of the Mausoleum of the Nanyue King

- Peasant Movement Training Institute, an important Maoist site

- Sacred Heart Cathedral (Stone House)

- Temple of Bright Filial Piety (Guangxiao)

- Temple of the Six Banyan Trees (Liurong), site of the Flowery Pagoda

- Sanyuan Palace

- Shamian or Shameen Island, the old trading compound

- Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, site of Guangzhou's former presidential palace

- Xiguan (Saikwan), the western suburbs of the old city

Pedestrian streets

editIn every district there are many shopping areas where people can walk on the sidewalks; however most of them are not set as pedestrian streets.

The popular pedestrian streets are:

- Beijing Road pedestrian street

- Shangxiajiu Pedestrian Street

- Huacheng Square (Flower City Square)

Malls and shopping centers

editThere are many malls and shopping centers in Guangzhou. The majority of the new malls are located in the Tianhe district.

- 101 Dynamics

- China Plaza

- Liwan Plaza

- Teem Plaza

- Victory Plaza

- Wanguo Plaza

- Grandview Mall (Grandview Mall Aquarium)

- Wanda square

- Happy Valley

- TaiKoo Hui

- Parc Central

- OneLinkWalk

- Rock Square

- Aeon Mall

- GT Land Plaza

- IFC Plaza

- IGC Mall

- Mall of the World

- K11

- Fashion Tianhe

Major buildings

edit-

Canton Custom House (est. 1916), one of the oldest surviving in China

-

Aiqun Hotel, Guangzhou's tallest building from 1937 to 1967

-

Our Lady of Lourdes Chapel on Shamian

-

The Canton Cement Factory (est. 1907), which housed Sun Yat-sen from 1923 to 1925

-

The old provincial capitol, now the Museum of Revolutionary History

Media

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

Guangzhou has two local radio stations: the provincial Radio Guangdong and the municipal Radio Guangzhou. Together they broadcast in more than a dozen channels. The primary language of both stations is Cantonese. Traditionally only one channel of Radio Guangdong is dedicated to Mandarin Chinese. However, in recent years there has been an increase in Mandarin programs on most Cantonese channels. Radio stations from cities around Guangzhou mainly broadcast in Cantonese and can be received in different parts of the city, depending on the radio stations' locations and transmission power. The Beijing-based China National Radio also broadcasts Mandarin programs in the city. Radio Guangdong has a 30-minute weekly English programs, Guangdong Today, which is broadcast globally through the World Radio Network. Daily English news programs are also broadcast by Radio Guangdong.

Guangzhou has some of the most notable Chinese-language newspapers and magazines in mainland China, most of which are published by three major newspaper groups in the city, the Guangzhou Daily Press Group, Nanfang Press Corporation, and the Yangcheng Evening News Group. The two leading newspapers of the city are Guangzhou Daily and Southern Metropolis Daily. The former, with a circulation of 1.8 million, has been China's most successful newspaper for 14 years in terms of advertising revenue, while Southern Metropolis Daily is considered one of the most liberal newspapers in mainland China. In addition to Guangzhou's Chinese-language publications, there are a few English magazines and newspapers. The most successful is That's Guangzhou, which started more than a decade ago and has since blossomed into That's PRD, producing expatriate magazines in Beijing and Shanghai as well. It also produces In the Red.

Education and research

editThe Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center, also known as Guangzhou University Town (广州大学城), is a large tertiary education complex located in the southeast suburbs of Guangzhou. It occupies the entirety of Xiaoguwei Island in Panyu District, covering an area of about 18 km2 (7 sq mi). The complex accommodates campuses from ten higher education institutions and can eventually accommodate up to 200,000 students, 20,000 teachers, and 50,000 staff.[211]

As of June 2023, Guangzhou hosts 84 institutions of higher education (excluding adult colleges), ranking 2nd nationwide after Beijing and 1st in South China region.[212] The city has many highly ranked educational institutions, with seven universities listed in 147 National Key Universities under the Double First-Class Construction, ranking fourth nationwide (after Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing). Guangzhou is also an important hub for international students and it was ranked 110th globally by the QS Best Student Cities Rankings in 2023.[213]

Guangzhou is a major Asia-Pacific R&D hub, ranking 8th globally, 4th in the Asia & Oceania regions after (Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing) and 1st in South Central China region.[214]

The Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center's higher education campuses are as follows:

- Guangdong Pharmaceutical University

- Guangdong University of Foreign Studies

- Guangdong University of Technology

- Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts

- Guangzhou University

- Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine

- South China Normal University

- South China University of Technology

- Sun Yat-sen University

- Xinghai Conservatory of Music

Guangzhou's other fully accredited and degree-granting universities and colleges include:

- Guangdong Institute of Science and Technology

- Guangdong Polytechnic Normal University

- Guangdong University of Finance & Economics

- Guangdong University of Finance

- Guangzhou College of South China University of Technology

- Guangzhou Medical University

- Guangzhou Sports University

- Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou)

- Jinan University

- South China Agricultural University

- Southern Medical University

- Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering

The two main comprehensive libraries are Guangzhou Library and Sun Yat-sen Library of Guangdong Province. Guangzhou Library is a public library in Guangzhou. The library has moved to a new building in Zhujiang New Town, which fully opened on June 23, 2013.[215] Sun Yat-sen Library of Guangdong Province has the largest collection of ancient books in Southern China.[216]

Notable people

edit- Choh Hao Li (1913–1987), American biochemist, expert on hormones

- Zhi Cong Li (born 1993), racing driver

- Xiao Ping Liang (born 1959), internationally exhibited calligrapher

- Kuang Sunmou (1863–?), railway engineer, businessman, and bureaucrat

- Bolo Yeung (born July 3, 1946), Hong Kong martial artist, competitive bodybuilder, and film actor

- Qi Yuwu (born November 28, 1976), actor based in Singapore

- Donnie Yen (born 27 July 1963), Hong Kong martial artist, action director and choreographer, and film director and actor

International relations

editTwin towns and sister cities

editConsulates General/consulates

editAs of April 2023, Guangzhou hosts 68 foreign consulates-general/consulates, excluding the Hong Kong and Macao trade office, making it one of the major cities to host more than 50 foreign representatives in China after Beijing and Shanghai.[23][24]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^

- UK: /ɡwæŋˈdʒoʊ/, gwang-JOH,[4] US: /ˈɡwɑːŋ-/, GWAHNG-[5]

- Chinese: 广州; pinyin: Guǎngzhōu

- Cantonese: [kʷɔ̌ːŋ.tsɐ̂u] or [kʷɔ̌ːŋ.tsɐ́u] ⓘ

References

edit- ^ 土地面积、人口密度(2008年). Statistics Bureau of Guangzhou. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ a b "China: Guăngdōng (Prefectures, Cities, Districts and Counties)". City Population. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "2021年广州Gdp达28231.97亿元 同比增8.1%-中新网". Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "Guangzhou". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Guangzhou". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Canton". Lexico UK English Dictionary UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Guangzhou". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "Illuminating China's Provinces, Municipalities and Autonomous Regions". PRC Central Government Official Website. Archived from the original on June 19, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ 海上丝绸之路的三大著名港口. People.cn. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Tourism Administration of Guangzhou Municipality". visitgz.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2010. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ Roberts, Toby; Williams, Ian; Preston, John (2020). "The Southampton system: A new universal standard approach for port-city classification". Maritime Policy & Management. 48 (4): 530–542. doi:10.1080/03088839.2020.1802785.

- ^ "Major Agglomerations of the World". City Population. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ 中央机构编制委员会印发《关于副省级市若干问题的意见》的通知. 中编发[1995]5号. docin.com. February 19, 1995. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ 全国乡镇规划确定五大中心城市. Southern Metropolitan Daily. February 9, 2010. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Mensah Obeng, Mark Kwaku (2018). "Journey to the East: a study of Ghanaian migrants in Guangzhou, China". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 53: 67–87. doi:10.1080/00083968.2018.1536557. S2CID 149595200.

- ^ Cheng, Andrew; Geng, Xiao (April 6, 2017). "Unlocking the potential of Chinese cities". China Daily. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Kawase, Kenji (January 25, 2021). "China's Guangzhou airport crowns itself the world's busiest for 2020". Nikkei Asia. Nikkei Inc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Top 10 Chinese cities by urban resident population". China Daily. November 18, 2022. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ Jin, Xin; Weber, Karin (September 16, 2008). "The China Import and Export (Canton) Fair: Past, Present, and Future". Journal of Convention & Event Tourism. 9 (3): 221–234. doi:10.1080/15470140802325863. hdl:10397/8520. S2CID 153995277.

- ^ "Guangzhou tops best mainland commercial cities rankings". chinadaily. December 16, 2014. Archived from the original on August 24, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- ^ "GaWC - The World According to GaWC 2020". www.lboro.ac.uk. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Global Financial Centres Index 28" (PDF). Long Finance. September 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "Consulates in Guangzhou, China". www.embassypages.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "CHINA EMBASSIES & CONSULATES". www.embassypages.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "Shimao Shenkong International Center·Hurun Global Rich List 2020". Hurun Report. February 26, 2020. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Leading 200 science cities Nature Index 2023 Science Cities Supplements". www.nature.com. Archived from the original on November 22, 2023. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ^ "Nature Index 2018 Science Cities". Nature Index. Archived from the original on October 2, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's Best Chinese Universities Ranking". ShanghaiRanking. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "US News Best Global Universities Rankings in Guangzhou". U.S. News & World Report. October 26, 2021. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ 番禺求证.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Xu, Jian (c. 720). 初學記 [Chuxueji, Records for Initial Studies] (in Traditional Chinese).

- ^ 中国古今地名大词典. Shanghai: Shanghai Cishu Press. 2005. p. 2901.

- ^ Yule, H. (1916). Cathay and the Way Thither. Vol. I. London: Hakluyt Society.

- ^ Versteegh, Kees; Mushira Eid (2005). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Vol. I. Brill. p. 378. ISBN 9789004144736.

- ^ Ng Wing Chung (2015). The Rise of Cantonese Opera. University of Illinois Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780252097096.

- ^ Chin, Angelina (2012). Bound to Emancipate: Working Women and Urban Citizenship in Early Twentieth-Century China and Hong Kong. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 202. ISBN 9781442215610.

- ^ The Chinese Repository. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Kraus. 1834.