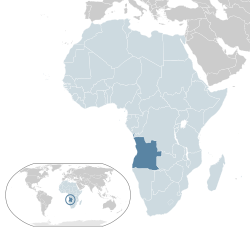

Angola,[a] officially the Republic of Angola,[b] is a country on the west-central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) country in both total area and population and is the seventh-largest country in Africa. It is bordered by Namibia to the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Zambia to the east, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. Angola has an exclave province, the province of Cabinda, that borders the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The capital and most populous city is Luanda.

Republic of Angola República de Angola (Portuguese) | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

| Anthem: "Angola Avante" (English: "Onwards Angola") | |

Major cities of Angola | |

| Capital and largest city | Luanda 8°50′S 13°20′E / 8.833°S 13.333°E |

| Official language | Portuguese |

| National languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2021)[1] | |

| Religion (2020)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Angolan |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| João Lourenço | |

| Esperança da Costa[3] | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Formation | |

| 11 November 1975 | |

| 22 November 1976 | |

| 21 January 2010 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,246,700 km2 (481,400 sq mi) (22nd) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | |

• Density | 24.97/km2 (64.7/sq mi) (157th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | 51.3[6] high inequality |

| HDI (2022) | medium (150th) |

| Currency | Angolan kwanza (AOA) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +244 |

| ISO 3166 code | AO |

| Internet TLD | .ao |

Angola has been inhabited since the Paleolithic Age. After the Bantu expansion reached the region, states were formed by the 13th century and organised into confederations. The Kingdom of Kongo ascended to achieve hegemony among the other kingdoms from the 14th century. Portuguese explorers established relations with Kongo in 1483. To the south were the kingdoms of Ndongo and Matamba, with the Ovimbundu kingdoms further south, and the Mbunda Kingdom in the east.[8][9]

The Portuguese began colonising the coast in the 16th century. Kongo fought three wars against the Portuguese, ending in the Portuguese conquest of Ndongo. The banning of the slave trade in the 19th century severely disrupted Kongo's undiversified economic system and European settlers gradually began to establish their presence in the interior of the region. The Portuguese colony that became Angola did not achieve its present borders until the early 20th century and experienced the strong resistance from the native groups such as the Cuamato, the Kwanyama, and the Mbunda. After a protracted anti-colonial struggle (1961–1974), Angola achieved independence in 1975 as a one-party Republic, but the country descended into a devastating civil war the same year, between the ruling People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), backed by the Soviet Union and Cuba; the insurgent National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, an originally Maoist and later anti-communist group supported by the United States and South Africa; the militant organization National Liberation Front of Angola, backed by Zaire; and the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda seeking the independence of the Cabinda exclave, also backed by Zaire.

Since the end of the civil war in 2002, Angola has emerged as a relatively stable constitutional republic, and its economy is among the fastest-growing in the world, with China, the European Union, and the United States being the country's largest investment and trade partners.[10][11][12] However, the economic growth is highly uneven, with most of the nation's wealth concentrated in a disproportionately small part of the population as most Angolans have a low standard of living; life expectancy is among the lowest in the world, while infant mortality is among the highest.[13]

Angola is a member of the United Nations, African Union, the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, and the Southern African Development Community. As of 2023[update], the Angolan population is estimated at 37.2 million.[14] Angolan culture reflects centuries of Portuguese influence, namely the predominance of the Portuguese language and of the Catholic Church, intermingled with a variety of indigenous customs and traditions.

Etymology

editThe name Angola comes from the Portuguese colonial name Reino de Angola ('Kingdom of Angola'), which appeared as early as Paulo Dias de Novais's 1571 charter.[15] The toponym was derived by the Portuguese from the title ngola, held by the kings of Ndongo and Matamba. Ndongo in the highlands, between the Kwanza and Lucala rivers, was nominally a possession of the Kingdom of Kongo. But in the 16th century it was seeking greater independence.[16]

History

editEarly migrations and political units

editModern Angola was populated predominantly by nomadic Khoi and San peoples prior to the first Bantu migrations. The Khoi and San peoples were hunter-gatherers, rather than practicing pastoralism or cultivation of crops.[17]

In the first millennium BC, they were displaced by Bantu peoples arriving from the north, most of whom likely originated in what is today northwestern Nigeria and southern Niger.[18] Bantu speakers introduced the cultivation of bananas and taro, as well as maintenance of large cattle herds, to Angola's central highlands and the Luanda plain. Due to a number of inhibiting geographic factors throughout the territory of Angola, namely harshly traversable land, hot/humid climate, and a plethora of deadly diseases, intermingling of pre-colonial tribes in Angola had been rare.[citation needed]

After settlement of the migrants, a number of political entities developed. The best-known of these was the Kingdom of Kongo, based in Angola. It extended northward to what are now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon. It established trade routes with other city-states and civilisations up and down the coast of southwestern and western Africa. Its traders even reached Great Zimbabwe and the Mutapa Empire, although the kingdom engaged in little or no trans-oceanic trade.[19] To its south lay the Kingdom of Ndongo, from which the area of the later Portuguese colony was sometimes known as Dongo. Next to that was the Kingdom of Matamba.[20] The lesser Kingdom of Kakongo to the north was later a vassal of the Kingdom of Kongo. The people in all of these states spoke Kikongo as a common language.

Portuguese colonization

editPortuguese explorer Diogo Cão reached the area in 1484.[20] The previous year, the Portuguese had established relations with the Kingdom of Kongo, which stretched at the time from modern Gabon in the north to the Kwanza River in the south. The Portuguese established their primary early trading post at Soyo, which is now the northernmost city in Angola apart from the Cabinda exclave.

Paulo Dias de Novais founded São Paulo de Loanda (Luanda) in 1575 with a hundred families of settlers and four hundred soldiers. Benguela was fortified in 1587 and became a township in 1617. An authoritarian state, the Kingdom of Kongo was highly centralised around its monarch and controlled neighbouring states as vassals. It had a strong economy, based on the industries of copper, ivory, salt, hides, and, to a lesser extent, slaves.[21] The transition from a feudal system of slavery to a capitalist one with Portugal would prove crucial to the history of the Kingdom of Kongo.[22]

As relations between Kongo and Portugal grew in the early 16th century, trade between the kingdoms also increased. Most of the trade was in palm cloth, copper, and ivory, but also increasing numbers of slaves.[22] Kongo exported few slaves, and its slave market had remained internal. But, following the development of a successful sugar-growing colony after Portuguese settlement of São Tomé, Kongo became a major source of slaves for the island's traders and plantations. Correspondence by King Afonso documents the purchase and sale of slaves within the country. His accounts also detail which slaves captured in war were given or sold to Portuguese merchants.[23]

Afonso continued to expand the kingdom of Kongo into the 1540s, expanding its borders to the south and east. The expansion of Kongo's population, coupled with Afonso's earlier religious reforms, allowed the ruler to centralize power in his capital and increase the power of the monarchy. He also established a royal monopoly on some trade.[23][22] To govern the growing slave trade, Afonso and several Portuguese kings claimed a joint monopoly on the external slave trade.[23][22]

The slave trade increasingly became Kongo's primary, and arguably sole, economic sector. A major obstacle for the Kingdom of Kongo was that slaves were the only commodity for which the European powers were willing to trade. Kongo lacked an effective international currency. Kongolese nobles could buy slaves with the national currency of nzimbu shells, which could be traded for slaves. These could be sold to gain international currency.

As the slave trade was the only commodity in which Europeans were interested in the region during the 16th and 17th centuries, the Kongo economy was unable to diversify or later industrialise outside of sectors in which slavery was involved, such as the arms industry.[24][25] The increased production and sale of guns within the kingdom was due to the salient issue of the slave trade, which had become an increasingly violent struggle. There was a constant need for slaves for the kings and queens to sell in exchange for foreign commodities, the absence of which would prevent them from having any influence with European powers such as Portugal and eventually the Dutch Republic.

Kongolese kings needed this influence to garner support from European powers for quelling internal rebellions. The situation became increasingly complicated during the rule of Garcia II, who needed the assistance of the Dutch military to drive out the Portuguese from Luanda, in spite of the fact that Portugal was Kongo's primary slave trading partner.[24]

By the early 17th century, the supply of foreign slaves captured by the Kongolese externally was waning. The government began to approve the enslavement of freeborn Kongolese citizens for relatively minor infractions, nearly any disobeying of the authoritarian system and the aristocracy. If several villagers were deemed guilty of a crime, it became relatively common for the whole village to be enslaved. The resulting chaos and internal conflict from Garcia II's reign would lead into that of his son and successor, António I. He was killed in 1665 by Portuguese at the Battle of Mbwila 1665, together with a substantial proportion of the aristocracy. The colonists were expanding their power.[26]

War broke out more widely in the Kingdom of Kongo after the death of António I.[25] Much of the stability and access to iron ore and charcoal necessary for gunsmiths to maintain the arms industry was disrupted. From then on, in this period almost every Kongolese citizen was in danger of being enslaved.[27][24] Many Kongolese subjects were adroit in making guns, and they were enslaved to have their skills available to colonists in the New World, where they worked as blacksmiths, ironworkers, and charcoal makers.[25]

The Portuguese established several other settlements, forts and trading posts along the Angolan coast, principally trading in Angolan slaves for plantations. Local slave dealers provided a large number of slaves for the Portuguese Empire,[28] usually in exchange for manufactured goods from Europe.[29][30] This part of the Atlantic slave trade continued until after Brazil's independence in the 1820s.[31]

Despite Portugal's territorial claims in Angola, its control over much of the country's vast interior was minimal.[20] In the 16th century Portugal gained control of the coast through a series of treaties and wars. Life for European colonists was difficult and progress was slow. John Iliffe notes that "Portuguese records of Angola from the 16th century show that a great famine occurred on average every seventy years; accompanied by epidemic disease, it might kill one-third or one-half of the population, destroying the demographic growth of a generation and forcing colonists back into the river valleys".[32]

During the Portuguese Restoration War, the Dutch West India Company occupied the principal settlement of Luanda in 1641, using alliances with local peoples to carry out attacks against Portuguese holdings elsewhere.[31] A fleet under Salvador de Sá retook Luanda in 1648; reconquest of the rest of the territory was completed by 1650. New treaties with the Kongo were signed in 1649; others with Njinga's Kingdom of Matamba and Ndongo followed in 1656. The conquest of Pungo Andongo in 1671 was the last major Portuguese expansion from Luanda, as attempts to invade Kongo in 1670 and Matamba in 1681 failed. Colonial outposts also expanded inward from Benguela, but until the late 19th century the inroads from Luanda and Benguela were very limited.[20] Hamstrung by a series of political upheavals in the early 1800s, Portugal was slow to mount a large scale annexation of Angolan territory.[31]

The slave trade was abolished in Angola in 1836, and in 1854 the colonial government freed all its existing slaves.[31] Four years later, a more progressive administration appointed by Portugal abolished slavery altogether. However, these decrees remained largely unenforceable, and the Portuguese depended on assistance from the British Royal Navy and what became known as the Blockade of Africa to enforce their ban on the slave trade.[31] This coincided with a series of renewed military expeditions into the bush.

By the mid-nineteenth century Portugal had established its dominion as far north as the Congo River and as far south as Mossâmedes.[31] Until the late 1880s, Portugal entertained proposals to link Angola with its colony in Mozambique but was blocked by British and Belgian opposition.[33] In this period, the Portuguese came up against different forms of armed resistance from various peoples in Angola.[34]

The Berlin Conference in 1884–1885 set the colony's borders, delineating the boundaries of Portuguese claims in Angola,[33] although many details were unresolved until the 1920s.[35] Trade between Portugal and its African territories rapidly increased as a result of protective tariffs, leading to increased development, and a wave of new Portuguese immigrants.[33]

Between 1939 and 1943, Portuguese army operations against the Mucubal, who they accused of rebellion and cattle-thieving, resulted in hundreds of Mucubal killed. During the campaign, 3,529 were taken prisoner, 20% of whom were women and children, and imprisoned in concentration camps. Many died in captivity from undernourishment, violence and forced labor. Around 600 were sent to Sao Tome and Principe. Hundreds were also sent to a camp in Damba, where 26% died.[36]

Angolan War of Independence

editUnder colonial law, black Angolans were forbidden from forming political parties or labour unions.[37] The first nationalist movements did not take root until after World War II, spearheaded by a largely Westernised and Portuguese-speaking urban class, which included many mestiços.[38] During the early 1960s they were joined by other associations stemming from ad hoc labour activism in the rural workforce.[37] Portugal's refusal to address increasing Angolan demands for self-determination provoked an armed conflict, which erupted in 1961 with the Baixa de Cassanje revolt and gradually evolved into a protracted war of independence that persisted for the next twelve years.[39] Throughout the conflict, three militant nationalist movements with their own partisan guerrilla wings emerged from the fighting between the Portuguese government and local forces, supported to varying degrees by the Portuguese Communist Party.[38][40]

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA) recruited from Bakongo refugees in Zaire.[41] Benefiting from particularly favourable political circumstances in Léopoldville, and especially from a common border with Zaire, Angolan political exiles were able to build up a power base among a large expatriate community from related families, clans, and traditions.[42] People on both sides of the border spoke mutually intelligible dialects and enjoyed shared ties to the historical Kingdom of Kongo.[42] Though as foreigners skilled Angolans could not take advantage of Mobutu Sese Seko's state employment programme, some found work as middlemen for the absentee owners of various lucrative private ventures. The migrants eventually formed the FNLA with the intention of making a bid for political power upon their envisaged return to Angola.[42]

A largely Ovimbundu guerrilla initiative against the Portuguese in central Angola from 1966 was spearheaded by Jonas Savimbi and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).[41] It remained handicapped by its geographic remoteness from friendly borders, the ethnic fragmentation of the Ovimbundu, and the isolation of peasants on European plantations where they had little opportunity to mobilise.[42]

During the late 1950s, the rise of the Marxist–Leninist Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in the east and Dembos hills north of Luanda came to hold special significance. Formed as a coalition resistance movement by the Angolan Communist Party,[39] the organisation's leadership remained predominantly Ambundu and courted public sector workers in Luanda.[41] Although both the MPLA and its rivals accepted material assistance from the Soviet Union or the People's Republic of China, the former harboured strong anti-imperialist views and was openly critical of the United States and its support for Portugal.[40] This allowed it to win important ground on the diplomatic front, soliciting support from nonaligned governments in Morocco, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, and the United Arab Republic.[39]

The MPLA attempted to move its headquarters from Conakry to Léopoldville in October 1961, renewing efforts to create a common front with the FNLA, then known as the Union of Angolan Peoples (UPA) and its leader Holden Roberto. Roberto turned down the offer.[39] When the MPLA first attempted to insert its own insurgents into Angola, the cadres were ambushed and annihilated by UPA partisans on Roberto's orders—setting a precedent for the bitter factional strife which would later ignite the Angolan Civil War.[39]

Angolan Civil War

editThroughout the war of independence, the three rival nationalist movements were severely hampered by political and military factionalism, as well as their inability to unite guerrilla efforts against the Portuguese.[43] Between 1961 and 1975 the MPLA, UNITA, and the FNLA competed for influence in the Angolan population and the international community.[43] The Soviet Union and Cuba became especially sympathetic towards the MPLA and supplied that party with arms, ammunition, funding, and training.[43] They also backed UNITA militants until it became clear that the latter was at irreconcilable odds with the MPLA.[44]

The collapse of Portugal's Estado Novo government following the 1974 Carnation Revolution suspended all Portuguese military activity in Africa and the brokering of a ceasefire pending negotiations for Angolan independence.[43] Encouraged by the Organisation of African Unity, Holden Roberto, Jonas Savimbi, and MPLA chairman Agostinho Neto met in Mombasa in early January 1975 and agreed to form a coalition government.[45] This was ratified by the Alvor Agreement later that month, which called for general elections and set the country's independence date for 11 November 1975.[45] All three factions, however, followed up on the ceasefire by taking advantage of the gradual Portuguese withdrawal to seize various strategic positions, acquire more arms, and enlarge their militant forces.[45] The rapid influx of weapons from numerous external sources, especially the Soviet Union and the United States, as well as the escalation of tensions between the nationalist parties, fueled a new outbreak of hostilities.[45] With tacit American and Zairean support the FNLA began massing large numbers of troops in northern Angola in an attempt to gain military superiority.[43] Meanwhile, the MPLA began securing control of Luanda, a traditional Ambundu stronghold.[43] Sporadic violence broke out in Luanda over the next few months after the FNLA attacked the MPLA's political headquarters in March 1975.[45][46] The fighting intensified with street clashes in April and May, and UNITA became involved after over two hundred of its members were massacred by an MPLA contingent that June.[45] An upswing in Soviet arms shipments to the MPLA influenced a decision by the Central Intelligence Agency to likewise provide substantial covert aid to the FNLA and UNITA.[47]

In August 1975, the MPLA requested direct assistance from the Soviet Union in the form of ground troops.[47] The Soviets declined, offering to send advisers but no troops; however, Cuba was more forthcoming and in late September dispatched nearly five hundred combat personnel to Angola, along with sophisticated weaponry and supplies.[44] By independence, there were over a thousand Cuban soldiers in the country.[47] They were kept supplied by a massive airbridge carried out with Soviet aircraft.[47] The persistent buildup of Cuban and Soviet military aid allowed the MPLA to drive its opponents from Luanda and blunt an abortive intervention by Zairean and South African troops, which had deployed in a belated attempt to assist the FNLA and UNITA.[45] The FNLA was largely annihilated after the decisive Battle of Quifangondo, although UNITA managed to withdraw its civil officials and militia from Luanda and seek sanctuary in the southern provinces.[43] From there, Savimbi continued to mount a determined insurgent campaign against the MPLA.[47]

Between 1975 and 1991, the MPLA implemented an economic and political system based on the principles of scientific socialism, incorporating central planning and a Marxist–Leninist one-party state.[48] It embarked on an ambitious programme of nationalisation, and the domestic private sector was essentially abolished.[48] Privately owned enterprises were nationalised and incorporated into a single umbrella of state-owned enterprises known as Unidades Economicas Estatais (UEE).[48] Under the MPLA, Angola experienced a significant degree of modern industrialisation.[48] However, corruption and graft also increased and public resources were either allocated inefficiently or simply embezzled by officials for personal enrichment.[49] The ruling party survived an attempted coup d'état by the Maoist-oriented Communist Organisation of Angola (OCA) in 1977, which was suppressed after a series of bloody political purges left thousands of OCA supporters dead.[50]

The MPLA abandoned its former Marxist ideology at its third party congress in 1990, and declared social democracy to be its new platform.[50] Angola subsequently became a member of the International Monetary Fund; restrictions on the market economy were also reduced in an attempt to draw foreign investment.[51] By May 1991 it reached a peace agreement with UNITA, the Bicesse Accords, which scheduled new general elections for September 1992.[51] When the MPLA secured a major electoral victory, UNITA objected to the results of both the presidential and legislative vote count and returned to war.[51] Following the election, the Halloween massacre occurred from 30 October to 1 November, where MPLA forces killed thousands of UNITA supporters.[52]

21st century

editOn 22 February 2002, government troops killed Savimbi in a skirmish in the Moxico province.[53] UNITA and the MPLA consented to the Luena Memorandum of Understanding in April; UNITA agreed to give up its armed wing.[54] With the elections in 2008 and 2012, an MPLA-ruled dominant-party system emerged, with UNITA and the FNLA as opposition parties.[55]

Angola has a serious humanitarian crisis; the result of the prolonged war, of the abundance of minefields, and the continued political agitation in favour of the independence of the exclave of Cabinda (carried out in the context of the protracted Cabinda conflict by the FLEC). While most of the internally displaced have now squatted around the capital, in musseques (shanty towns) the general situation for Angolans remains desperate.[56][57]

A drought in 2016 caused the worst food crisis in Southern Africa in 25 years, affecting 1.4 million people across seven of Angola's eighteen provinces. Food prices rose and acute malnutrition rates doubled, impacting over 95,000 children.[58]

José Eduardo dos Santos stepped down as President of Angola after 38 years in 2017, being peacefully succeeded by João Lourenço, Santos' chosen successor.[59] Some members of the dos Santos family were later linked to high levels of corruption. In July 2022, ex-president José Eduardo dos Santos died in Spain.[60]

In August 2022, the ruling party, MPLA, won another majority and President Lourenço won a second five-year term in the election. However, the election was the tightest in Angola's history.[61]

Geography

editAt 1,246,700 km2 (481,400 sq mi),[62] Angola is the world's twenty-second largest country – comparable in size to Mali, or twice the size of France or of Texas. It lies mostly between latitudes 4° and 18°S, and longitudes 12° and 24°E.

Angola borders Namibia to the south, Zambia to the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north-east and the South Atlantic Ocean to the west.

The coastal exclave of Cabinda in the north has borders with the Republic of the Congo to the north and with the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south.[63] Angola has a favorable coastline for maritime trade, with four natural harbors: Luanda, Lobito, Moçâmedes, and Porto Alexandre. These natural indentations contrast with Africa's typical coastline of rocky cliffs and deep bays.[64] Angola's capital, Luanda, lies on the Atlantic coast in the northwest of the country.[65]

Angola had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.35/10, ranking it 23rd globally out of 172 countries.[66] In Angola forest cover is around 53% of the total land area, equivalent to 66,607,380 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, down from 79,262,780 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 65,800,190 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 807,200 hectares (ha). Of the naturally regenerating forest 40% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity) and around 3% of the forest area was found within protected areas. For the year 2015, 100% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership. [67] [68]

Climate

editLike the rest of tropical Africa, Angola experiences distinct, alternating rainy and dry seasons.[69] In the north, the rainy season may last for as long as seven months—usually from September to April, with perhaps a brief slackening in January or February.[69] In the south, the rainy season begins later, in November, and lasts until about February.[69] The dry season (cacimbo) is often characterized by a heavy morning mist.[69] In general, precipitation is higher in the north, but at any latitude it is greater in the interior than along the coast and increases with altitude.[69] Temperatures fall with distance from the equator and with altitude and tend to rise closer to the Atlantic Ocean.[69] Thus, at Soyo, at the mouth of the Congo River, the average annual temperature is about 26 °C, but it is under 16 °C at Huambo on the temperate central plateau.[69] The coolest months are July and August (in the middle of the dry season), when frost may sometimes form at higher altitudes.[69]

Due to climate change, Angola's annual average temperature has increased by 1.4.°C since 1951, and is expected to keep rising[70] while rainfall is becoming more variable.[71] Angola is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts.[72] Natural hazards such as floods, erosion, droughts, and epidemics (e.g.: malaria, cholera and typhoid fever) are expected to worsen with climate change. Rising sea levels also pose a significant risk to Angola's coastal areas, where around 50% of the population lives.[73]

In 2023 Angola emitted 174.71 million tonnes of greenhouse gases, around 0.32% of the world's total emissions, making it the 46th highest emitting country.[74] In its Nationally Determined Contribution, Angola has pledged a 14% reduction in its greenhouse gas emissions by 2025 and an additional 10% reduction conditional on international support.[75] According to the World Bank, achieving climate resilience in Angola requires diversifying the country's economy away from its dependence on oil.[70]

Wildlife

editGovernment and politics

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

The Angolan government is composed of three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial. The executive branch of the government is composed of the President, the vice-presidents and the Council of Ministers.

The legislative branch comprises a 220-seat unicameral legislature, the National Assembly of Angola, elected from multi-member province-wide and nationwide constituencies using party-list proportional representation. For decades, political power has been concentrated in the presidency.[76]

After 38 years of rule, in 2017 President dos Santos stepped down from MPLA leadership.[77] The leader of the winning party at the parliamentary elections in August 2017 would become the next president of Angola. The MPLA selected the former Defense Minister João Lourenço as Santos' chosen successor.[78]

In what has been described as a political purge[79] to cement his power and reduce the influence of the Dos Santos family, Lourenço subsequently sacked the chief of the national police, Ambrósio de Lemos, and the head of the intelligence service, Apolinário José Pereira. Both are considered allies of former president Dos Santos.[80] He also removed Isabel dos Santos, daughter of the former president, as head of the country's state oil company Sonangol.[81] In August 2020, José Filomeno dos Santos, son of Angola's former president, was sentenced for five years in jail for fraud and corruption.[82]

Constitution

editThe Constitution of 2010 establishes the broad outlines of government structure and delineates the rights and duties of citizens. The legal system is based on Portuguese law and customary law but is weak and fragmented, and courts operate in only 12 of more than 140 municipalities.[83] A Supreme Court serves as the appellate tribunal; a Constitutional Court does not hold the powers of judicial review.[4] Governors of the 18 provinces are appointed by the president. After the end of the civil war, the regime came under pressure from within as well as from the international community to become more democratic and less authoritarian. Its reaction was to implement a number of changes without substantially changing its character.[84]

The new constitution, adopted in 2010, did away with presidential elections, introducing a system in which the president and the vice-president of the political party that wins the parliamentary elections automatically become president and vice-president. Directly or indirectly, the president controls all other organs of the state, so there is de facto no separation of powers.[85] In the classifications used in constitutional law, this government falls under the category of authoritarian regime.[86]

Justice

editA Supreme Court serves as a court of appeal. The Constitutional Court is the supreme body of the constitutional jurisdiction, established with the approval of Law no. 2/08, of 17 June – Organic Law of the Constitutional Court and Law n. 3/08, of 17 June – Organic Law of the Constitutional Process. The legal system is based on Portuguese and customary law. There are 12 courts in more than 140 counties in the country. Its first task was the validation of the candidacies of the political parties to the legislative elections of 5 September 2008. Thus, on 25 June 2008, the Constitutional Court was institutionalized and its Judicial Counselors assumed the position before the President of the Republic. Currently, seven advisory judges are present, four men and three women.[citation needed]

In 2014, a new penal code took effect in Angola. The classification of money-laundering as a crime is one of the novelties in the new legislation.[87]

Administrative divisions

editAs of September 2024[update], Angola is divided into twenty-one provinces (províncias) and 162 municipalities. The municipalities are further divided into 559 communes (townships).[88] The provinces are:

| Number | Province | Capital | Area (km2)[89] | Population (2014 Census)[90] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bengo | Caxito | 31,371 | 356,641 |

| 2 | Benguela | Benguela | 39,826 | 2,231,385 |

| 3 | Bié | Cuíto | 70,314 | 1,455,255 |

| 4 | Cabinda | Cabinda | 7,270 | 716,076 |

| 5 | Cuando | Mavinga | ? | ? |

| 6 | Cuanza Norte | N'dalatando | 24,110 | 443,386 |

| 7 | Cuanza Sul | Sumbe | 55,600 | 1,881,873 |

| 8 | Cubango | Menongue | ? | ? |

| 9 | Cunene | Ondjiva | 87,342 | 990,087 |

| 10 | Huambo | Huambo | 34,270 | 2,019,555 |

| 11 | Huíla | Lubango | 79,023 | 2,497,422 |

| 12 | Icolo e Bengo | Catete | ? | ? |

| 13 | Luanda | Luanda | 2,417 | 6,945,386 |

| 14 | Lunda Norte | Dundo | 103,760 | 862,566 |

| 15 | Lunda Sul | Saurimo | 77,637 | 537,587 |

| 16 | Malanje | Malanje | 97,602 | 986,363 |

| 17 | Moxico Leste | Cazombo | ? | ? |

| 18 | Moxico | Luena | 223,023 | 758,568 |

| 19 | Namibe | Moçâmedes | 57,091 | 495,326 |

| 20 | Uíge | Uíge | 58,698 | 1,483,118 |

| 21 | Zaire | M'banza-Kongo | 40,130 | 594,428 |

Exclave of Cabinda

editWith an area of approximately 7,283 square kilometres (2,812 sq mi), the Northern Angolan province of Cabinda is unusual in being separated from the rest of the country by a strip, some 60 kilometres (37 mi) wide, of the Democratic Republic of Congo along the lower Congo River. Cabinda borders the Congo Republic to the north and north-northeast and the DRC to the east and south. The town of Cabinda is the chief population centre.

According to a 1995 census, Cabinda had an estimated population of 600,000, approximately 400,000 of whom are citizens of neighboring countries. Population estimates are, however, highly unreliable. Consisting largely of tropical forest, Cabinda produces hardwoods, coffee, cocoa, crude rubber, and palm oil.

The product for which it is best known, however, is its oil, which has given it the nickname the Kuwait of Africa. Cabinda's petroleum production from its considerable offshore reserves now accounts for more than half of Angola's output.[91] Most of the oil along its coast was discovered under Portuguese rule by the Cabinda Gulf Oil Company (CABGOC) from 1968 onwards.

Ever since Portugal handed over sovereignty of its former overseas province of Angola to the local independence groups (MPLA, UNITA and FNLA), the territory of Cabinda has been a focus of separatist guerrilla actions opposing the Government of Angola (which has employed its armed forces, the FAA—Forças Armadas Angolanas) and Cabindan separatists.

Foreign relations

editAngola is a founding member state of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth, an international organization and political association of Lusophone nations across four continents, where Portuguese is an official language.

On 16 October 2014, Angola was elected for the second time a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, with 190 favorable votes out of a total of 193. The term of office began on 1 January 2015 and expired on 31 December 2016.[92]

Since January 2014, the Republic of Angola has been chairing the International Conference for the Great Lakes Region (CIRGL). [80] In 2015, CIRGL Executive Secretary Ntumba Luaba said that Angola is the example to be followed by the members of the organization, due to the significant progress made during the 12 years of peace, namely in terms of socio-economic stability and political-military.[93]

Military

editThe Angolan Armed Forces (Forças Armadas Angolanas, FAA) are headed by a Chief of Staff who reports to the Minister of Defence. There are three divisions—the Army (Exército), Navy (Marinha de Guerra, MGA) and National Air Force (Força Aérea Nacional, FAN). Total manpower is 107,000; plus paramilitary forces of 10,000 (2015 est.).[94]

Its equipment includes Russian-manufactured fighters, bombers and transport planes. There are also Brazilian-made EMB-312 Tucanos for training, Czech-made L-39 Albatroses for training and bombing, and a variety of western-made aircraft such as the C-212\Aviocar, Sud Aviation Alouette III, etc. A small number of FAA personnel are stationed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) and 500 more were deployed in March 2023 due to the resurgence of the M23.[95][96] The FAA has also participated in the Southern African Development Community (SADC)'s mission for peace in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique.[97]

Police

editThe National Police departments are Public Order, Criminal Investigation, Traffic and Transport, Investigation and Inspection of Economic Activities, Taxation and Frontier Supervision, Riot Police and the Rapid Intervention Police. The National Police are in the process of standing up an air wing,[when?] to provide helicopter support for operations. The National Police are developing their criminal investigation and forensic capabilities. The force consists of an estimated 6,000 patrol officers, 2,500 taxation and frontier supervision officers, 182 criminal investigators, 100 financial crimes detectives, and approximately 90 economic activity inspectors.[citation needed]

The National Police have implemented a modernisation and development plan to increase the capabilities and efficiency of the total force. In addition to administrative reorganisation, modernisation projects include procurement of new vehicles, aircraft and equipment, construction of new police stations and forensic laboratories, restructured training programmes and the replacement of AKM rifles with 9 mm Uzis for officers in urban areas.

Human rights

editAngola was classified as 'not free' by Freedom House in the Freedom in the World 2014 report[98] and the 2024 report,[99] however the report has noted increases in freedoms under João Lourenço. The 2014 report noted that the August 2012 parliamentary elections, in which the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola won more than 70% of the vote, suffered from serious flaws, including outdated and inaccurate voter rolls.[98] Voter turnout dropped from 80% in 2008 to 60%.[98]

A 2012 report by the U.S. Department of State said, "The three most important human rights abuses [in 2012] were official corruption and impunity; limits on the freedoms of assembly, association, speech, and press; and cruel and excessive punishment, including reported cases of torture and beatings as well as unlawful killings by police and other security personnel."[100]

Angola ranked forty-two of forty-eight sub-Saharan African states on the 2007 Index of African Governance list and scored poorly on the 2013 Ibrahim Index of African Governance.[101]: 8 It was ranked 39 out of 52 sub-Saharan African countries, scoring particularly badly in the areas of participation and human rights, sustainable economic opportunity and human development. The Ibrahim Index uses a number of variables to compile its list which reflects the state of governance in Africa.[102]

In 2019, homosexual acts were decriminalized in Angola, and the government also prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation. The vote was overwhelming: 155 for, 1 against, 7 abstaining.[103]

Economy

editAngola has diamonds, oil, gold, copper and rich wildlife (which was dramatically depleted during the civil war), forest and fossil fuels. Since independence, oil and diamonds have been the most important economic resource. Smallholder and plantation agriculture dramatically dropped in the Angolan Civil War, but began to recover after 2002.

Angola's economy has in recent years moved on from the disarray caused by a quarter-century of Angolan civil war to become the fastest-growing economy in Africa and one of the fastest-growing in the world, with an average GDP growth of 20% between 2005 and 2007.[104] In the period 2001–10, Angola had the world's highest annual average GDP growth, at 11.1%.

In 2004, the Exim Bank of China approved a $2 billion line of credit to Angola, to be used for rebuilding Angola's infrastructure, and to limit the influence of the International Monetary Fund there.[105]

China is Angola's biggest trade partner and export destination as well as a significant source of imports. Bilateral trade reached $27.67 billion in 2011, up 11.5% year-on-year. China's imports, mainly crude oil and diamonds, increased 9.1% to $24.89 billion while China's exports to Angola, including mechanical and electrical products, machinery parts and construction materials, surged 38.8%.[106] The oil glut led to a local price for unleaded gasoline of £0.37 a gallon.[107]

As of 2021, the biggest import partners were the European Union, followed by China, Togo, the United States, and Brazil.[11] More than half of Angola's exports go to China, followed by a significantly smaller amount to India, the European Union, and the United Arab Emirates.[12]

The Angolan economy grew 18% in 2005, 26% in 2006 and 17.6% in 2007. Due to the global recession, the economy contracted an estimated −0.3% in 2009.[4] The security brought about by the 2002 peace settlement has allowed the resettlement of 4 million displaced persons and a resulting large-scale increase in agriculture production. Angola's economy is expected to grow by 3.9 per cent in 2014 said the International Monetary Fund (IMF), robust growth in the non-oil economy, mainly driven by a very good performance in the agricultural sector, is expected to offset a temporary drop in oil production.[108]

Angola's financial system is maintained by the National Bank of Angola and managed by the governor Jose de Lima Massano. According to a study on the banking sector, carried out by Deloitte, the monetary policy led by Banco Nacional de Angola (BNA), the Angolan national bank, allowed a decrease in the inflation rate put at 7.96% in December 2013, which contributed to the sector's growth trend.[109] Estimates released by Angola's central bank, said the country's economy should grow at an annual average rate of 5 per cent over the next four years, boosted by the increasing participation of the private sector.[110] Angola was ranked 133rd in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[111]

Although the country's economy has grown significantly since Angola achieved political stability in 2002, mainly due to fast-rising earnings in the oil sector, Angola faces huge social and economic problems. These are in part a result of almost continual armed conflict from 1961 on, although the highest level of destruction and socio-economic damage took place after the 1975 independence, during the long years of civil war. However, high poverty rates and blatant social inequality chiefly stems from persistent authoritarianism, "neo-patrimonial" practices at all levels of the political, administrative, military and economic structures, and of a pervasive corruption.[112][113] The main beneficiaries are political, administrative, economic and military power holders, who have accumulated (and continue to accumulate) enormous wealth.[114]

"Secondary beneficiaries" are the middle strata that are about to become social classes. However, almost half the population has to be considered poor, with dramatic differences between the countryside and the cities, where slightly more than 50% of the people reside.[citation needed]

A study carried out in 2008 by the Angolan Instituto Nacional de Estatística found that in rural areas roughly 58% must be classified as "poor" according to UN norms but in the urban areas only 19%, and an overall rate of 37%.[115] In cities, a majority of families, well beyond those officially classified as poor, must adopt a variety of survival strategies.[116][clarification needed] In urban areas social inequality is most evident and it is extreme in Luanda.[117] In the Human Development Index Angola constantly ranks in the bottom group.[118]

In January 2020, a leak of government documents known as the Luanda Leaks showed that U.S. consulting companies such as Boston Consulting Group, McKinsey & Company, and PricewaterhouseCoopers had helped members of the family of former President José Eduardo dos Santos (especially his daughter Isabel dos Santos) corruptly run Sonangol for their own personal profit, helping them use the company's revenues to fund vanity projects in France and Switzerland.[119] After further revelations in the Pandora Papers, former generals Dias and do Nascimento and former presidential advisers were also accused of misappropriating significant public funds for personal benefit.[120]

The enormous differences between the regions pose a serious structural problem for the Angolan economy, illustrated by the fact that about one third of economic activities are concentrated in Luanda and neighbouring Bengo province, while several areas of the interior suffer economic stagnation and even regression.[121]

One of the economic consequences of social and regional disparities is a sharp increase in Angolan private investments abroad. The small fringe of Angolan society where most of the asset accumulation takes place seeks to spread its assets, for reasons of security and profit. For the time being, the biggest share of these investments is concentrated in Portugal where the Angolan presence (including the family of the state president) in banks as well as in the domains of energy, telecommunications, and mass media has become notable, as has the acquisition of vineyards and orchards as well as of tourism enterprises.[122]

Angola has upgraded critical infrastructure, an investment made possible by funds from the country's development of oil resources.[123] According to a report, just slightly more than ten years after the end of the civil war Angola's standard of living has overall greatly improved. Life expectancy, which was just 46 years in 2002, reached 51 in 2011. Mortality rates for children fell from 25 per cent in 2001 to 19 per cent in 2010 and the number of students enrolled in primary school has tripled since 2001.[124] However, at the same time the social and economic inequality that has characterised the country for so long has not diminished, but has deepened in all respects.

With a stock of assets corresponding to 70 billion Kz (US$6.8 billion), Angola is now the third-largest financial market in sub-Saharan Africa, surpassed only by Nigeria and South Africa. According to the Angolan Minister of Economy, Abraão Gourgel, the financial market of the country grew modestly since 2002 and now occupies third place in sub-Saharan Africa.[125]

On 19 December 2014, the Capital Market in Angola was launched. BODIVA (Angola Stock Exchange and Derivatives, in English) was allocated the secondary public debt market, and was expected to launch the corporate debt market by 2015, though the stock market itself was only expected to commence trading in 2016.[126]

Natural resources

editThe Economist reported in 2008 that diamonds and oil make up 60% of Angola's economy, almost all of the country's revenue and all of its dominant exports.[127] Growth is almost entirely driven by rising oil production which surpassed 1.4 million barrels per day (220,000 m3/d) in late 2005 and was expected to grow to 2 million barrels per day (320,000 m3/d) by 2007. Control of the oil industry is consolidated in Sonangol Group, a conglomerate owned by the Angolan government. In December 2006, Angola was admitted as a member of OPEC.[128] In 2022, the country produced an average of 1.165 million barrels of oil per day, according to Agência Nacional de Petróleo, Gás e Biocombustíveis (ANPG), the national oil, gas and biofuels agency.[129]

According to the Heritage Foundation, a conservative American think tank, oil production from Angola has increased so significantly that Angola now is China's biggest supplier of oil.[130] "China has extended three multi-billion dollar lines of credit to the Angolan government; two loans of $2 billion from China Exim Bank, one in 2004, the second in 2007, as well as one loan in 2005 of $2.9 billion from China International Fund Ltd."[131]

Growing oil revenues also created opportunities for corruption: according to a recent Human Rights Watch report, US$32 billion disappeared from government accounts in 2007–2010.[132] Furthermore, Sonangol, the state-run oil company, controls 51% of Cabinda's oil. Due to this market control, the company ends up determining the profit received by the government and the taxes it pays. The council of foreign affairs states that the World Bank mentioned that Sonangol is a taxpayer, it carries out quasi-fiscal activities, it invests public funds, and, as concessionaire, it is a sector regulator. This multifarious work program creates conflicts of interest and characterises a complex relationship between Sonangol and the government that weakens the formal budgetary process and creates uncertainty as regards the actual fiscal stance of the state."[133]

In 2002, Angola demanded compensation for oil spills allegedly caused by Chevron Corporation, the first time it had fined a multinational corporation operating in its waters.[134]

Operations in its diamond mines include partnerships between state-run Endiama and mining companies such as ALROSA which operate in Angola.[135]

Access to biocapacity in Angola is higher than world average. In 2016, Angola had 1.9 global hectares[136] of biocapacity per person within its territory, slightly more than world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[137] In 2016, Angola used 1.01 global hectares of biocapacity per person – their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use about half as much biocapacity as Angola contains. As a result, Angola is running a biocapacity reserve.[136]

Agriculture

editAgriculture and forestry is an area of potential opportunity for the country. The African Economic Outlook organization states that "Angola requires 4.5 million tonnes a year of grain but grows only about 55% of the maize it needs, 20% of the rice and just 5% of its required wheat".[138]

In addition, the World Bank estimates that "less than 3 per cent of Angola's abundant fertile land is cultivated and the economic potential of the forestry sector remains largely unexploited".[139]

Before independence in 1975, Angola was a bread-basket of southern Africa and a major exporter of bananas, coffee and sisal, but three decades of civil war destroyed fertile countryside, left it littered with landmines and drove millions into the cities. The country now depends on expensive food imports, mainly from South Africa and Portugal, while more than 90% of farming is done at the family and subsistence level. Thousands of Angolan small-scale farmers are trapped in poverty.[140]

Transport

editTransport in Angola consists of:

- Three separate railway systems totalling 2,761 km (1,716 mi)

- 76,626 km (47,613 mi) of highway of which 19,156 km (11,903 mi) is paved

- 1,295 navigable inland waterways

- five major sea ports

- 243 airports, of which 32 are paved.

Angola centers its port trade in five main ports: Namibe, Lobito, Soyo, Cabinda and Luanda. The port of Luanda is the largest of the five, as well as being one of the busiest on the African continent.[141]

Two trans-African automobile routes pass through Angola: the Tripoli-Cape Town Highway and the Beira-Lobito Highway. Travel on highways outside of towns and cities in Angola (and in some cases within) is[when?] often not best advised for those without four-by-four vehicles. While reasonable road infrastructure has existed within Angola, time and war have taken their toll on the road surfaces, leaving many severely potholed, littered with broken asphalt. In many areas drivers have established alternative tracks to avoid the worst parts of the surface, although careful attention must be paid to the presence or absence of landmine warning markers by the side of the road. The Angolan government has contracted the restoration of many of the country's roads. The road between Lubango and Namibe, for example, was completed recently with funding from the European Union,[142] and is comparable to many European main routes. Completing the road infrastructure is likely to take some decades, but substantial efforts are already being made.[citation needed]

The old airport in Luanda, Quatro de Fevereiro Airport, will be replaced by the new Dr. Antonio Agostinho Neto International Airport.

Telecommunications

editThe telecommunications industry is considered one of the main strategic sectors in Angola.[143]

In October 2014, the building of an optic fiber underwater cable was announced.[144] This project aims to turn Angola into a continental hub, thus improving Internet connections both nationally and internationally.[145]

On 11 March 2015, the First Angolan Forum of Telecommunications and Information Technology was held in Luanda under the motto "The challenges of telecommunications in the current context of Angola",[146] to promote debate on topical issues on telecommunications in Angola and worldwide.[147] A study of this sector, presented at the forum, said Angola had the first telecommunications operator in Africa to test LTE – with speeds up to 400 Mbit/s – and mobile penetration of about 75%; there are about 3.5 million smartphones in the Angolan market; There are about 25,000 kilometres (16,000 miles) of optical fibre installed in the country.[148][149]

The first Angolan satellite, AngoSat-1, was launched into orbit on 26 December 2017.[150] It was launched from the Baikonur space center in Kazakhstan on board a Zenit 3F rocket. The satellite was built by Russia's RSC Energia, a subsidiary of the state-run space industry player Roscosmos. The satellite payload was supplied by Airbus Defence & Space.[151] Due to an on-board power failure during solar panel deployment, on 27 December, RSC Energia revealed that they lost communications contact with the satellite. Although, subsequent attempts to restore communications with the satellite were successful, the satellite eventually stopped sending data and RSC Energia confirmed that AngoSat-1 was inoperable. The launch of AngoSat-1 was aimed at ensuring telecommunications throughout the country.[152] According to Aristides Safeca, Secretary of State for Telecommunications, the satellite was aimed at providing telecommunications services, TV, internet and e-government and was expected to remain in operation "at best" for 18 years.[153]

A replacement satellite named AngoSat-2 was pursued and was expected to be in service by 2020.[154] As of February 2021, Ango-Sat-2 was about 60% ready. The officials reported the launch was expected in about 17 months, by July 2022.[155] The launch of AngoSat-2 occurred on 12 October 2022.[156]

Technology

editThe management of the top-level domain '.ao' passed from Portugal to Angola in 2015, following new legislation.[157] A joint decree of Minister of Telecommunications and Information Technologies José Carvalho da Rocha and the minister of Science and Technology, Maria Cândida Pereira Teixeira, states that "under the massification" of that Angolan domain, "conditions are created for the transfer of the domain root '.ao' of Portugal to Angola".[158]

Demographics

editAngola has a population of 24,383,301 inhabitants according to the preliminary results of its 2014 census, the first one conducted or carried out since 15 December 1970.[159] It is composed of Ovimbundu (language Umbundu) 37%, Ambundu (language Kimbundu) 23%, Bakongo 13%, and 32% other ethnic groups (including the Chokwe, the Ovambo, the Ganguela and the Xindonga) as well as about 2% mulattos (mixed European and African), 1.6% Chinese and 1% European.[4] The Ambundu and Ovimbundu ethnic groups combined form a majority of the population, at 62%.[160][161] However, on 23 March 2016, official data revealed by Angola's National Statistic Institute – Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), states that Angola has a population of 25,789,024 inhabitants.

It is estimated that Angola was host to 12,100 refugees and 2,900 asylum seekers by the end of 2007. 11,400 of those refugees were originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who arrived in the 1970s.[162] As of 2008[update] there were an estimated 400,000 Democratic Republic of the Congo migrant workers,[163] at least 220,000 Portuguese,[164] and about 259,000 Chinese living in Angola.[165] 1 million Angolans are mixed race (black and white). Also, 40,000 Vietnamese live in the country.[10][13]

Since 2003, more than 400,000 Congolese migrants have been expelled from Angola.[166] Prior to independence in 1975, Angola had a community of approximately 350,000 Portuguese,[167][168] but the vast majority left after independence and the ensuing civil war. However, Angola has recovered its Portuguese minority in recent years; currently, there are about 200,000 registered with the consulates, and increasing due to the debt crisis in Portugal and the relative prosperity in Angola.[169] The Chinese population stands at 258,920, mostly composed of temporary migrants.[170] Also, there is a small Brazilian community of about 5,000 people.[171] The Roma were deported to Angola from Portugal.[172]

As of 2007[update], the total fertility rate of Angola is 5.54 children born per woman (2012 estimates), the 11th highest in the world.[4]

Urbanization

edit| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luanda Lubango |

1 | Luanda | Luanda | 6,759,313 | Huambo Benguela | ||||

| 2 | Lubango | Huíla | 600,751 | ||||||

| 3 | Huambo | Huambo | 595,304 | ||||||

| 4 | Benguela | Benguela | 555,124 | ||||||

| 5 | Cabinda | Cabinda | 550,000 | ||||||

| 6 | Malanje | Malanje | 455,000 | ||||||

| 7 | Saurimo | Lunda Sul | 393,000 | ||||||

| 8 | Lobito | Benguela | 357,950 | ||||||

| 9 | Cuíto | Bié | 355,423 | ||||||

| 10 | Uíge | Uíge | 322,531 | ||||||

Languages

editThe languages in Angola are those originally spoken by the different ethnic groups and Portuguese, introduced during the Portuguese colonial era. The most widely spoken indigenous languages are Umbundu, Kimbundu and Kikongo, in that order. Portuguese is the official language of the country.

Although the exact numbers of those fluent in Portuguese or who speak Portuguese as a first language are unknown, a 2012 study mentions that Portuguese is the first language of 39% of the population.[174] In 2014, a census carried out by the Instituto Nacional de Estatística in Angola mentions that 71.15% of the nearly 25.8 million inhabitants of Angola (meaning around 18.3 million people) use Portuguese as a first or second language.[175]

According to the 2014 census, Portuguese is spoken by 71.1% of Angolans, Umbundu by 23%, Kikongo by 8.2%, Kimbundu by 7.8%, Chokwe by 6.5%, Nyaneka by 3.4%, Ngangela by 3.1%, Fiote by 2.4%, Kwanyama by 2.3%, Muhumbi by 2.1%, Luvale by 1%, and other languages by 4.1%.[176]

Religion

editThere are about 1,000 religious communities, mostly Christian, in Angola.[177] While reliable statistics are nonexistent, estimates have it that more than half of the population are Catholics, while about a quarter adhere to the Protestant churches introduced during the colonial period: the Congregationalists mainly among the Ovimbundu of the Central Highlands and the coastal region to its west, the Methodists concentrating on the Kimbundu speaking strip from Luanda to Malanje, the Baptists almost exclusively among the Bakongo of the north-west (now present in Luanda as well) and dispersed Adventists, Reformed, and Lutherans.[178][179]

Religion in Angola (2015)[180]

In Luanda and region there subsists a nucleus of the "syncretic" Tocoists and in the north-west a sprinkling of Kimbanguism can be found, spreading from the Congo/Zaïre. Since independence, hundreds of Pentecostal and similar communities have sprung up in the cities, whereby now about 50% of the population is living; several of these communities/churches are of Brazilian origin.

As of 2008[update] the U.S. Department of State estimates the Muslim population at 80,000–90,000, less than 1% of the population,[181] while the Islamic Community of Angola puts the figure closer to 500,000.[182] Muslims consist largely of migrants from West Africa and the Middle East (especially Lebanon), although some are local converts.[183] The Angolan government does not legally recognize any Muslim organizations and often shuts down mosques or prevents their construction.[184]

In a study assessing nations' levels of religious regulation and persecution with scores ranging from 0 to 10 where 0 represented low levels of regulation or persecution, Angola was scored 0.8 on Government Regulation of Religion, 4.0 on Social Regulation of Religion, 0 on Government Favoritism of Religion and 0 on Religious Persecution.[185]

Foreign missionaries were very active prior to independence in 1975, although since the beginning of the anti-colonial fight in 1961 the Portuguese colonial authorities expelled a series of Protestant missionaries and closed mission stations based on the belief that the missionaries were inciting pro-independence sentiments. Missionaries have been able to return to the country since the early 1990s, although security conditions due to the civil war have prevented them until 2002 from restoring many of their former inland mission stations.[186]

The Catholic Church and some major Protestant denominations mostly keep to themselves in contrast to the "New Churches" which actively proselytize. Catholics, as well as some major Protestant denominations, provide help for the poor in the form of crop seeds, farm animals, medical care and education.[187][188]

Health

editEpidemics of cholera, malaria, rabies and African hemorrhagic fevers like Marburg hemorrhagic fever, are common diseases in several parts of the country. Many regions in this country have high incidence rates of tuberculosis and high HIV prevalence rates. Dengue, filariasis, leishmaniasis and onchocerciasis (river blindness) are other diseases carried by insects that also occur in the region. Angola has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the world and one of the world's lowest life expectancies. A 2007 survey concluded that low and deficient niacin status was common in Angola.[189] Demographic and Health Surveys is currently conducting several surveys in Angola on malaria, domestic violence and more.[190]

In September 2014, the Angolan Institute for Cancer Control (IACC) was created by presidential decree, and it will integrate the National Health Service in Angola.[191] The purpose of this new centre is to ensure health and medical care in oncology, policy implementation, programmes and plans for prevention and specialised treatment.[192] This cancer institute will be assumed as a reference institution in the central and southern regions of Africa.[193]

In 2014, Angola launched a national campaign of vaccination against measles, extended to every child under ten years old and aiming to go to all 18 provinces in the country.[194] The measure is part of the Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Measles 2014–2020 created by the Angolan Ministry of Health which includes strengthening routine immunisation, a proper dealing with measles cases, national campaigns, introducing a second dose of vaccination in the national routine vaccination calendar and active epidemiological surveillance for measles. This campaign took place together with the vaccination against polio and vitamin A supplementation.[195]

A yellow fever outbreak, the worst in the country in three decades[196] began in December 2015. By August 2016, when the outbreak began to subside, nearly 4,000 people were suspected of being infected. As many as 369 may have died. The outbreak began in the capital, Luanda, and spread to at least 16 of the 18 provinces. In the 2024 Global Hunger Index (GHI), Angola has a serious level of hunger and ranks 103rd out of 127 countries. Angola's GHI score is 26.6[197]

Education

editAlthough by law education in Angola is compulsory and free for eight years, the government reports that a percentage of pupils are not attending due to a lack of school buildings and teachers.[198] Pupils are often responsible for paying additional school-related expenses, including fees for books and supplies.[198]

In 1999, the gross primary enrollment rate was 74 per cent and in 1998, the most recent year for which data are available, the net primary enrollment rate was 61 per cent.[198] Gross and net enrollment ratios are based on the number of pupils formally registered in primary school and therefore do not necessarily reflect actual school attendance.[198] There continue to be significant disparities in enrollment between rural and urban areas. In 1995, 71.2 per cent of children ages 7 to 14 years were attending school.[198] It is reported that higher percentages of boys attend school than girls.[198] During the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), nearly half of all schools were reportedly looted and destroyed, leading to current problems with overcrowding.[198]

The Ministry of Education recruited 20,000 new teachers in 2005 and continued to implement teacher training.[198] Teachers tend to be underpaid, inadequately trained and overworked (sometimes teaching two or three shifts a day).[198] Some teachers may reportedly demand payment or bribes directly from their pupils.[198] Other factors, such as the presence of landmines, lack of resources and identity papers, and poor health prevent children from regularly attending school.[198] Although budgetary allocations for education were increased in 2004, the education system in Angola continues to be extremely under-funded.[198]

According to estimates by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the adult literacy rate in 2011 was 70.4%.[199] By 2015, this had increased to 71.1%.[200] 82.9% of men and 54.2% of women are literate as of 2001.[201] Since independence from Portugal in 1975, a number of Angolan students continued to be admitted every year at high schools, polytechnical institutes and universities in Portugal and Brazil through bilateral agreements; in general, these students belong to the elites.

In September 2014, the Angolan Ministry of Education announced an investment of 16 million Euros in the computerisation of over 300 classrooms across the country. The project also includes training teachers at a national level, "as a way to introduce and use new information technologies in primary schools, thus reflecting an improvement in the quality of teaching".[202]

In 2010, the Angolan government started building the Angolan Media Libraries Network, distributed throughout several provinces in the country to facilitate the people's access to information and knowledge. Each site has a bibliographic archive, multimedia resources and computers with Internet access, as well as areas for reading, researching and socialising.[203] The plan envisages the establishment of one media library in each Angolan province by 2017. The project also includes the implementation of several media libraries, in order to provide the several contents available in the fixed media libraries to the most isolated populations in the country.[204] At this time, the mobile media libraries are already operating in the provinces of Luanda, Malanje, Uíge, Cabinda and Lunda South. As for REMA, the provinces of Luanda, Benguela, Lubango and Soyo have currently working media libraries.[205]

Culture

editAngolan culture has been heavily influenced by Portuguese culture, especially in language and religion, and the culture of the indigenous ethnic groups of Angola, predominantly Bantu culture.

The diverse ethnic communities—the Ovimbundu, Ambundu, Bakongo, Chokwe, Mbunda and other peoples—to varying degrees maintain their own cultural traits, traditions and languages, but in the cities, where slightly more than half of the population now lives, a mixed culture has been emerging since colonial times; in Luanda, since its foundation in the 16th century.

In this urban culture, Portuguese heritage has become more and more dominant. African roots are evident in music and dance and is moulding the way in which Portuguese is spoken. This process is well reflected in contemporary Angolan literature, especially in the works of Angolan authors.

In 2014, Angola resumed the National Festival of Angolan Culture after a 25-year break. The festival took place in all the provincial capitals and lasted for 20 days, with the theme "Culture as a Factor of Peace and Development.[206]

Media

editCinema

editIn 1972, one of Angola's first feature films, Sarah Maldoror's internationally co-produced Sambizanga, was released at the Carthage Film Festival to critical acclaim, winning the Tanit d'Or, the festival's highest prize.[207]

Sports

editBasketball is the second most popular sport in Angola. Its national team has won the AfroBasket 11 times and holds the record of most titles. As a top team in Africa, it is a regular competitor at the Summer Olympic Games and the FIBA World Cup. Angola is home to one of Africa's first competitive leagues.[208] Bruno Fernando, a player for the Atlanta Hawks, is the only current NBA player from Angola.[citation needed]

In football, Angola hosted the 2010 Africa Cup of Nations. The Angola national football team qualified for the 2006 FIFA World Cup, their first appearance in the World Cup finals. They were eliminated after one defeat and two draws in the group stage. They won three COSAFA Cups and finished runner-up in the 2011 African Nations Championship.

Angola has participated in the World Women's Handball Championship for several years. The country has also appeared in the Summer Olympics for seven years and both regularly competes in and once has hosted the FIRS Roller Hockey World Cup, where the best finish is sixth. Angola is also often believed to have historic roots in the martial art "Capoeira Angola" and "Batuque" which were practised by enslaved African Angolans transported as part of the Atlantic slave trade.[209]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ /ænˈɡoʊlə/ ⓘ an-GOH-lə; Portuguese: [ɐ̃ˈɡɔlɐ]; Kongo: Ngola, pronounced [ŋɔla]

- ^ Portuguese: República de Angola

References

edit- ^ "Main ethnic groups in Angola 2021". Statista. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Angola: Major World Religions (1900–2050)". The Association of Religion Data Archives. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Investidura do Presidente da República Archived 27 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Rádio Nacional de Angola. 15 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Angola". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023. (Archived 2023 edition.)

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Angola)". International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ Gini index

- ^ "Human Development Report 2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Gordon, David M. (26 September 2018), "Kingdoms of South-Central Africa: Sources, Historiography, and History", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.146, ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4, retrieved 22 October 2024

- ^ Thornton, John K., ed. (2020), "The Development of States in West Central Africa to 1540", A History of West Central Africa to 1850, New Approaches to African History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 16–55, ISBN 978-1-107-56593-7, retrieved 22 October 2024

- ^ a b Transparency and Accountability in Angola, Human Rights Watch, 13 April 2010, archived from the original on 6 October 2015, retrieved 1 April 2016

- ^ a b "Foreign import trade partners of Angola (2021)". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on 29 December 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Foreign export trade partners of Angola (2021)". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on 29 December 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Life expectancy at birth". World Fact Book. United States Central Intelligence Agency. 2014. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ "Angola Population (2024) – Worldometer". worldometers.info. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Heywood, Linda M.; Thornton, John K. (2007). Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585–1660. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0521770651. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015.

- ^ Leander (18 May 2016). "Kingdom of Kongo 1390–1914". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Henderson, Lawrence (1979). Angola: Five Centuries of Conflict. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-0812216202.

- ^ Miller, Joseph (1979). Kings and Kinsmen: Early Mbundu States in Angola. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0198227045.

- ^ "The Story of Africa". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 45

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of the Ancient Kongo Kingdom". Africa Rebirth. 20 November 2023. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Heywood, Linda M. "Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491–1800." The Journal of African History 50, no. 1 (2009): 1–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40206695.

- ^ a b c Atmore, Anthony and Oliver (2001). Medieval Africa, 1250–1800. p. 171.

- ^ a b c "Kingdom of Kongo 1390–1914". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Rinquist, John: Kongo Iron: Symbolic Power, Superior Technology and Slave Wisdom, African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter, Volume 11, Issue 3, September 2008, Article 3, pp.14–15

- ^ Thornton, John K: Warfare in Atlantic Africa 1500–1800, 1999. Routledge. Page 103.

- ^ Thornton, John K: The Kongolese Saint Anthonty: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706, page 69. Cambridge University, 1998

- ^ Fleisch, Axel (2004). "Angola: Slave Trade, Abolition of". In Shillington, Kevin (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History. Vol. 1. Routledge. pp. 131–133. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- ^ Angola President Jose Eduardo Dos Santos Handbook. Int'l Business Publications USA. 1 January 2006. p. 153. ISBN 0739716069.

- ^ "The History of Brazil–Africa Relations". Bridging the Atlantic (PDF). p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Collelo, Thomas, ed. (1991). Angola, a Country Study. Area Handbook Series (Third ed.). Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, American University. pp. 14–26. ISBN 978-0160308444.

- ^ Iliffe, John (2007) Africans: the history of a continent Archived 10 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-521-68297-5. For valuable complements for the 16th and 17th centuries see Beatrix Heintze, Studien zur Geschichte Angolas im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, Colónia/Alemanha: Köppe, 1996

- ^ a b c Corrado, Jacopo (2008). The Creole Elite and the Rise of Angolan Protonationalism: 1870–1920. Amherst, New York: Cambria Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-1604975291.

- ^ See René Pélissier, Les guerres grises: Résistance et revoltes en Angola, (1845-1941), Éditions Pélissier, Montamets, 78630 Orgeval (France), 1977

- ^ See René Pélissier, La colonie du Minotaure. Nationalismes et révoltes en Angola (1926–1961), éditions Pélissier, Montamets, 78630 Orgeval (France), 1979

- ^ Coca de Campos, Rafael (2022). "Kakombola: O genocídio dos Mucubais na Angola Colonial, 1930 – 1943". Atena Editora (in Portuguese). doi:10.22533/at.ed.663221201. ISBN 978-65-5983-766-3.

- ^ a b Okoth, Assa (2006). A History of Africa: African nationalism and the de-colonisation process. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. pp. 143–147. ISBN 9966-25-358-0.

- ^ a b Dowden, Richard (2010). Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles. London: Portobello Books. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-1-58648-753-9.

- ^ a b c d e Cornwell, Richard (1 November 2000). "The War of Independence" (PDF). Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ a b Stockwell, John (1979) [1978]. In Search of Enemies. London: Futura Publications Limited. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0393009262.

- ^ a b c Hanlon, Joseph (1986). Beggar Your Neighbours: Apartheid Power in Southern Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0253331311.

- ^ a b c d Chabal, Patrick (2002). A History of Postcolonial Lusophone Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0253215659.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rothschild, Donald (1997). Managing Ethnic Conflict in Africa: Pressures and Incentives for Cooperation. Washington: The Brookings Institution. pp. 115–120. ISBN 978-0815775935.