In mathematics, a Hadamard matrix, named after the French mathematician Jacques Hadamard, is a square matrix whose entries are either +1 or −1 and whose rows are mutually orthogonal. In geometric terms, this means that each pair of rows in a Hadamard matrix represents two perpendicular vectors, while in combinatorial terms, it means that each pair of rows has matching entries in exactly half of their columns and mismatched entries in the remaining columns. It is a consequence of this definition that the corresponding properties hold for columns as well as rows.

The n-dimensional parallelotope spanned by the rows of an n × n Hadamard matrix has the maximum possible n-dimensional volume among parallelotopes spanned by vectors whose entries are bounded in absolute value by 1. Equivalently, a Hadamard matrix has maximal determinant among matrices with entries of absolute value less than or equal to 1 and so is an extremal solution of Hadamard's maximal determinant problem.

Certain Hadamard matrices can almost directly be used as an error-correcting code using a Hadamard code (generalized in Reed–Muller codes), and are also used in balanced repeated replication (BRR), used by statisticians to estimate the variance of a parameter estimator.

Properties

editLet H be a Hadamard matrix of order n. The transpose of H is closely related to its inverse. In fact:

where In is the n × n identity matrix and HT is the transpose of H. To see that this is true, notice that the rows of H are all orthogonal vectors over the field of real numbers and each have length Dividing H through by this length gives an orthogonal matrix whose transpose is thus its inverse. Multiplying by the length again gives the equality above. As a result,

where det(H) is the determinant of H.

Suppose that M is a complex matrix of order n, whose entries are bounded by |Mij | ≤ 1, for each i, j between 1 and n. Then Hadamard's determinant bound states that

Equality in this bound is attained for a real matrix M if and only if M is a Hadamard matrix.

The order of a Hadamard matrix must be 1, 2, or a multiple of 4.[1]

Proof

editThe proof of the nonexistence of Hadamard matrices with dimensions other than 1, 2, or a multiple of 4 follows:

If , then there is at least one scalar product of 2 rows which has to be 0. The scalar product is a sum of n values each of which is either 1 or −1, therefore the sum is odd for odd n, so n must be even.

If with , and there exists an Hadamard matrix , then it has the property that for any :

Now we define the matrix by setting . Note that has all 1s in row 0. We check that is also a Hadamard matrix:

Row 1 and row 2, like all other rows except row 0, must have entries of 1 and entries of −1 each. (*)

Let denote the number of 1s of row 2 beneath 1s in row 1. Let denote the number of −1s of row 2 beneath 1s in row 1. Let denote the number of 1s of row 2 beneath −1s in row 1. Let denote the number of −1s of row 2 beneath −1s in row 1.

Row 2 has to be orthogonal to row 1, so the number of products of entries of the rows resulting in 1, , has to match those resulting in −1, . Due to (*), we also have , from which we can express and and substitute:

But we have as the number of 1s in row 1 the odd number , contradiction.

Sylvester's construction

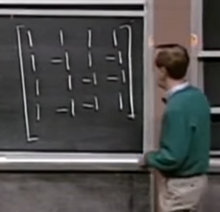

editExamples of Hadamard matrices were actually first constructed by James Joseph Sylvester in 1867. Let H be a Hadamard matrix of order n. Then the partitioned matrix

is a Hadamard matrix of order 2n. This observation can be applied repeatedly and leads to the following sequence of matrices, also called Walsh matrices.

and

for , where denotes the Kronecker product.

In this manner, Sylvester constructed Hadamard matrices of order 2k for every non-negative integer k.[2]

Sylvester's matrices have a number of special properties. They are symmetric and, when k ≥ 1 (2k > 1), have trace zero. The elements in the first column and the first row are all positive. The elements in all the other rows and columns are evenly divided between positive and negative. Sylvester matrices are closely connected with Walsh functions.

Alternative construction

editIf we map the elements of the Hadamard matrix using the group homomorphism , we can describe an alternative construction of Sylvester's Hadamard matrix. First consider the matrix , the matrix whose columns consist of all n-bit numbers arranged in ascending counting order. We may define recursively by

It can be shown by induction that the image of the Hadamard matrix under the above homomorphism is given by

This construction demonstrates that the rows of the Hadamard matrix can be viewed as a length linear error-correcting code of rank n, and minimum distance with generating matrix

This code is also referred to as a Walsh code. The Hadamard code, by contrast, is constructed from the Hadamard matrix by a slightly different procedure.

Hadamard conjecture

editThe most important open question in the theory of Hadamard matrices is one of existence. Specifically, the Hadamard conjecture proposes that a Hadamard matrix of order 4k exists for every positive integer k. The Hadamard conjecture has also been attributed to Paley, although it was considered implicitly by others prior to Paley's work.[3]

A generalization of Sylvester's construction proves that if and are Hadamard matrices of orders n and m respectively, then is a Hadamard matrix of order nm. This result is used to produce Hadamard matrices of higher order once those of smaller orders are known.

Sylvester's 1867 construction yields Hadamard matrices of order 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, etc. Hadamard matrices of orders 12 and 20 were subsequently constructed by Hadamard (in 1893).[4] In 1933, Raymond Paley discovered the Paley construction, which produces a Hadamard matrix of order q + 1 when q is any prime power that is congruent to 3 modulo 4 and that produces a Hadamard matrix of order 2(q + 1) when q is a prime power that is congruent to 1 modulo 4.[5] His method uses finite fields.

The smallest order that cannot be constructed by a combination of Sylvester's and Paley's methods is 92. A Hadamard matrix of this order was found using a computer by Baumert, Golomb, and Hall in 1962 at JPL.[6] They used a construction, due to Williamson,[7] that has yielded many additional orders. Many other methods for constructing Hadamard matrices are now known.

In 2005, Hadi Kharaghani and Behruz Tayfeh-Rezaie published their construction of a Hadamard matrix of order 428.[8] As a result, the smallest order for which no Hadamard matrix is presently known is 668.

By 2014, there were 12 multiples of 4 less than 2000 for which no Hadamard matrix of that order was known.[9] They are: 668, 716, 892, 1132, 1244, 1388, 1436, 1676, 1772, 1916, 1948, and 1964.

Equivalence and uniqueness

editTwo Hadamard matrices are considered equivalent if one can be obtained from the other by negating rows or columns, or by interchanging rows or columns. Up to equivalence, there is a unique Hadamard matrix of orders 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12. There are 5 inequivalent matrices of order 16, 3 of order 20, 60 of order 24, and 487 of order 28. Millions of inequivalent matrices are known for orders 32, 36, and 40. Using a coarser notion of equivalence that also allows transposition, there are 4 inequivalent matrices of order 16, 3 of order 20, 36 of order 24, and 294 of order 28.[10]

Hadamard matrices are also uniquely recoverable, in the following sense: If an Hadamard matrix of order has entries randomly deleted, then with overwhelming likelihood, one can perfectly recover the original matrix from the damaged one. The algorithm of recovery has the same computational cost as matrix inversion.[11]

Special cases

editMany special cases of Hadamard matrices have been investigated in the mathematical literature.

Skew Hadamard matrices

editA Hadamard matrix H is skew if A skew Hadamard matrix remains a skew Hadamard matrix after multiplication of any row and its corresponding column by −1. This makes it possible, for example, to normalize a skew Hadamard matrix so that all elements in the first row equal 1.

Reid and Brown in 1972 showed that there exists a doubly regular tournament of order n if and only if there exists a skew Hadamard matrix of order n + 1. In a mathematical tournament of order n, each of n players plays one match against each of the other players, each match resulting in a win for one of the players and a loss for the other. A tournament is regular if each player wins the same number of matches. A regular tournament is doubly regular if the number of opponents beaten by both of two distinct players is the same for all pairs of distinct players. Since each of the n(n − 1)/2 matches played results in a win for one of the players, each player wins (n − 1)/2 matches (and loses the same number). Since each of the (n − 1)/2 players defeated by a given player also loses to (n − 3)/2 other players, the number of player pairs (i, j ) such that j loses both to i and to the given player is (n − 1)(n − 3)/4. The same result should be obtained if the pairs are counted differently: the given player and any of the n − 1 other players together defeat the same number of common opponents. This common number of defeated opponents must therefore be (n − 3)/4. A skew Hadamard matrix is obtained by introducing an additional player who defeats all of the original players and then forming a matrix with rows and columns labeled by players according to the rule that row i, column j contains 1 if i = j or i defeats j and −1 if j defeats i. This correspondence in reverse produces a doubly regular tournament from a skew Hadamard matrix, assuming the skew Hadamard matrix is normalized so that all elements of the first row equal 1.[12]

Regular Hadamard matrices

editRegular Hadamard matrices are real Hadamard matrices whose row and column sums are all equal. A necessary condition on the existence of a regular n × n Hadamard matrix is that n be a square number. A circulant matrix is manifestly regular, and therefore a circulant Hadamard matrix would have to be of square order. Moreover, if an n × n circulant Hadamard matrix existed with n > 1 then n would necessarily have to be of the form 4u 2 with u odd.[13][14]

Circulant Hadamard matrices

editThe circulant Hadamard matrix conjecture, however, asserts that, apart from the known 1 × 1 and 4 × 4 examples, no such matrices exist. This was verified for all but 26 values of u less than 104.[15]

Generalizations

editOne basic generalization is a weighing matrix. A weighing matrix is a square matrix in which entries may also be zero and which satisfies for some w, its weight. A weighing matrix with its weight equal to its order is a Hadamard matrix.[16]

Another generalization defines a complex Hadamard matrix to be a matrix in which the entries are complex numbers of unit modulus and which satisfies H H* = n In where H* is the conjugate transpose of H. Complex Hadamard matrices arise in the study of operator algebras and the theory of quantum computation. Butson-type Hadamard matrices are complex Hadamard matrices in which the entries are taken to be qth roots of unity. The term complex Hadamard matrix has been used by some authors to refer specifically to the case q = 4.

Practical applications

edit- Olivia MFSK – an amateur-radio digital protocol designed to work in difficult (low signal-to-noise ratio plus multipath propagation) conditions on shortwave bands.

- Balanced repeated replication (BRR) – a technique used by statisticians to estimate the variance of a statistical estimator.

- Coded aperture spectrometry – an instrument for measuring the spectrum of light. The mask element used in coded aperture spectrometers is often a variant of a Hadamard matrix.

- Feedback delay networks – Digital reverberation devices which use Hadamard matrices to blend sample values

- Plackett–Burman design of experiments for investigating the dependence of some measured quantity on a number of independent variables.

- Robust parameter designs for investigating noise factor impacts on responses

- Compressed sensing for signal processing and under-determined linear systems (inverse problems)

- Quantum Hadamard gate for quantum computing and the Hadamard transform for quantum algorithms.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Hadamard Matrices and Designs" (PDF). UC Denver. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ J.J. Sylvester. Thoughts on inverse orthogonal matrices, simultaneous sign successions, and tessellated pavements in two or more colours, with applications to Newton's rule, ornamental tile-work, and the theory of numbers. Philosophical Magazine, 34:461–475, 1867

- ^ Hedayat, A.; Wallis, W. D. (1978). "Hadamard matrices and their applications". Annals of Statistics. 6 (6): 1184–1238. doi:10.1214/aos/1176344370. JSTOR 2958712. MR 0523759..

- ^ Hadamard, J. (1893). "Résolution d'une question relative aux déterminants". Bulletin des Sciences Mathématiques. 17: 240–246.

- ^ Paley, R. E. A. C. (1933). "On orthogonal matrices". Journal of Mathematics and Physics. 12 (1–4): 311–320. doi:10.1002/sapm1933121311.

- ^ Baumert, L.; Golomb, S. W.; Hall, M. Jr. (1962). "Discovery of an Hadamard Matrix of Order 92". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 68 (3): 237–238. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1962-10761-7. MR 0148686.

- ^ Williamson, J. (1944). "Hadamard's determinant theorem and the sum of four squares". Duke Mathematical Journal. 11 (1): 65–81. doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-44-01108-7. MR 0009590.

- ^ Kharaghani, H.; Tayfeh-Rezaie, B. (2005). "A Hadamard matrix of order 428". Journal of Combinatorial Designs. 13 (6): 435–440. doi:10.1002/jcd.20043. S2CID 17206302.

- ^ Đoković, Dragomir Ž; Golubitsky, Oleg; Kotsireas, Ilias S. (2014). "Some new orders of Hadamard and Skew-Hadamard matrices". Journal of Combinatorial Designs. 22 (6): 270–277. arXiv:1301.3671. doi:10.1002/jcd.21358. S2CID 26598685.

- ^ Wanless, I.M. (2005). "Permanents of matrices of signed ones". Linear and Multilinear Algebra. 53 (6): 427–433. doi:10.1080/03081080500093990. S2CID 121547091.

- ^ Kline, J. (2019). "Geometric search for Hadamard matrices". Theoretical Computer Science. 778: 33–46. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2019.01.025. S2CID 126730552.

- ^ Reid, K.B.; Brown, Ezra (1972). "Doubly regular tournaments are equivalent to skew hadamard matrices". Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A. 12 (3): 332–338. doi:10.1016/0097-3165(72)90098-2.

- ^ Turyn, R. J. (1965). "Character sums and difference sets". Pacific Journal of Mathematics. 15 (1): 319–346. doi:10.2140/pjm.1965.15.319. MR 0179098.

- ^ Turyn, R. J. (1969). "Sequences with small correlation". In Mann, H. B. (ed.). Error Correcting Codes. New York: Wiley. pp. 195–228.

- ^ Schmidt, B. (1999). "Cyclotomic integers and finite geometry". Journal of the American Mathematical Society. 12 (4): 929–952. doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-99-00298-2. hdl:10356/92085. JSTOR 2646093.

- ^ Geramita, Anthony V.; Pullman, Norman J.; Wallis, Jennifer S. (1974). "Families of weighing matrices". Bulletin of the Australian Mathematical Society. 10 (1). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 119–122. doi:10.1017/s0004972700040703. ISSN 0004-9727. S2CID 122560830.

Further reading

edit- Baumert, L. D.; Hall, Marshall (1965). "Hadamard matrices of the Williamson type". Math. Comp. 19 (91): 442–447. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1965-0179093-2. MR 0179093.

- Georgiou, S.; Koukouvinos, C.; Seberry, J. (2003). "Hadamard matrices, orthogonal designs and construction algorithms". Designs 2002: Further computational and constructive design theory. Boston: Kluwer. pp. 133–205. ISBN 978-1-4020-7599-5.

- Goethals, J. M.; Seidel, J. J. (1970). "A skew Hadamard matrix of order 36". J. Austral. Math. Soc. 11 (3): 343–344. doi:10.1017/S144678870000673X. S2CID 14193297.

- Kimura, Hiroshi (1989). "New Hadamard matrix of order 24". Graphs and Combinatorics. 5 (1): 235–242. doi:10.1007/BF01788676. S2CID 39169723.

- Mood, Alexander M. (1964). "On Hotelling's Weighing Problem". Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 17 (4): 432–446. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177730883.

- Reid, K. B.; Brown, E. (1972). "Doubly regular tournaments are equivalent to skew Hadamard matrices". J. Combin. Theory Ser. A. 12 (3): 332–338. doi:10.1016/0097-3165(72)90098-2.

- Seberry Wallis, Jennifer (1976). "On the existence of Hadamard matrices". J. Comb. Theory A. 21 (2): 188–195. doi:10.1016/0097-3165(76)90062-5.

- Seberry, Jennifer (1980). "A construction for generalized hadamard matrices". J. Statist. Plann. Infer. 4 (4): 365–368. doi:10.1016/0378-3758(80)90021-X.

- Seberry, J.; Wysocki, B.; Wysocki, T. (2005). "On some applications of Hadamard matrices". Metrika. 62 (2–3): 221–239. doi:10.1007/s00184-005-0415-y. S2CID 40646.

- Spence, Edward (1995). "Classification of hadamard matrices of order 24 and 28". Discrete Math. 140 (1–3): 185–242. doi:10.1016/0012-365X(93)E0169-5.

- Yarlagadda, R. K.; Hershey, J. E. (1997). Hadamard Matrix Analysis and Synthesis. Boston: Kluwer. ISBN 978-0-7923-9826-4.

External links

edit- Skew Hadamard matrices of all orders up to 100, including every type with order up to 28;

- "Hadamard Matrix". in OEIS

- N. J. A. Sloane. "Library of Hadamard Matrices".

- On-line utility to obtain all orders up to 1000, except 668, 716, 876 & 892.

- R-Package to generate Hadamard Matrices using R

- JPL: In 1961, mathematicians from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Caltech worked together to construct a Hadamard Matrix containing 92 rows and columns