Gunggamarandu (meaning "river boss" in Barunggam and Wakka Wakka) is an extinct monospecific genus of tomistomine crocodilian from Pliocene-Pleistocene aged deposits in the Darling Downs (possibly the Riversleigh lagerstätte) of Australia. Gunggamarandu represents the first tomistomine known from Oceania and it is also the southernmost known tomistomine to date. The type, and only known, species is Gunggamarandu maunala (meaning "head hole", after the Barunggam words for such), which was described by Jorgo Ristevski et al. in 2021.[1]

| Gunggamarandu | |

|---|---|

| |

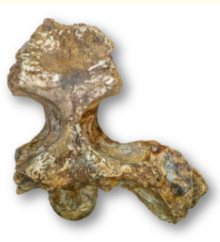

| Holotype cranium QMF14.548 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Gavialidae |

| Subfamily: | Tomistominae |

| Genus: | †Gunggamarandu Ristevski et al., 2021 |

| Species | |

| |

Discovery and naming

editThe holotype of Gunggamarandu, QMF14.548 (a partial cranium), was discovered no later than the 1870s, probably around 1875, and it was part of the "old collection" at the Queensland Museum in Brisbane[2] and QMF14.548 was later accessioned into the Queensland Museum collection on January 8, 1914. In 1995, Salisbury et al. suggested that QMF14.548 may have been a gavialoid.[3] QMF14.548 was formally described in 2021 by Jorgo Ristevski et al. and it was named Gunggamarandu maunala.[1] It was found in a layer of rock in the Darling Downs in Australia, which dates to the Pliocene-Pleistocene ages, sometime around 5–2 million years ago.[4] The western Darling Downs is predominantly Pliocene, while the rest is mainly Pleistocene, but since it is unknown exactly where in the Darling Downs the holotype of Gunggamarandu was discovered, its exact age is unknown.

Description

editUpon describing Gunggamarandu, Ristevski et al. (2021) stated that Gunggamarandu was a large-sized animal. No size estimates were given, but they did estimate that the skull would have been at least 80 centimetres (2.6 ft) when complete.[1] Some sources outside of Ristevski et al. (2021) estimate that Gunggamarandu may have grown up to 7 metres (23 ft) long when fully grown.[5]

Classification

editSalisbury et al. (1995) classified the then unnamed Gunggamarandu as a possible gavialoid,[3] while Ristevski et al. (2021), who formally named and described the animal, placed Gunggamarandu into the Tomistominae as the sister taxon to Dollosuchoides,[1] although its precise position in the group is uncertain due to the scant nature of the holotype. The authors also found Gunggamarandu morphologically distinct from all other known Australian crocodylians, thus by default making Gunggamarandu not referable to Mekosuchinae or even closely related to Crocodylus.[1]

The results of the analysis can be shown in the cladogram below:

| Crocodylia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

editIn the Darling Downs, where the holotype was discovered,[1] Gunggamarandu would have shared its habitat with a number of species, such as: several species of bandicoots (Peramelidae), the marsupials Diprotodon, Euryzygoma, Palorchestes and Thylacoleo, and it may have competed in the same, or a similar ecological niche, to the mekosuchine crocodylian Paludirex and possibly also an unnamed species of Ziphodont crocodile, which was the second found in the area in 150 years since around 1860.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f Ristevski J, Price GJ, Weisbecker V, Salisbury SW (2021). "First record of a tomistomine crocodylian from Australia". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): Article number 12158. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1112158R. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-91717-y. PMC 8190066. PMID 34108569.

- ^ Mather, P. (1986). A Time for a Museum: A History of the Queensland Museum 1862–1986, Vol. 24 (Memoirs of the Queensland Museum).

- ^ a b Salisbury, S. W., Molnar, R. E. & Willis, P. M. (1995) A. Fossil gavial from the Pleistocene of Darling Downs, southeastern Queensland. Wellington Caves Quaternary Symposium

- ^ Molnar, R.E, Kurz, C. (1997). The distribution of Pleistocene vertebrates on the eastern Darling Downs, based on the Queensland Museum collections. Proc. Linn. Soc. N. S. W. 117:107–134.

- ^ "Mystery solved as skull of ancient 7-metre croc identified". NITV. 14 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ De Vis, C.W. (1886). "On remains of an extinct saurian". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland. 2: 181–191.