This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2011) |

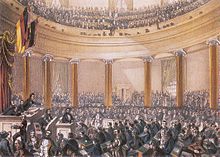

The Frankfurt National Assembly (German: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung) was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of the Austrian Empire,[1] elected on 1 May 1848 (see German federal election, 1848).[2]

Frankfurt National Assembly Frankfurter Nationalversammlung | |

|---|---|

| German Empire | |

Imperial Coat of arms | |

| History | |

| Founded | 18 May 1848 |

| Disbanded | 30 May 1849 |

| Preceded by | Federal Convention |

| Succeeded by | Federal Convention |

| Leadership | |

President | Frederich Lang (first) Wilhelm Loewe (last) |

Prime Minister | |

| Elections | |

First election | 1848 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| St. Paul's Church, Frankfurt am Main | |

| Stuttgart (rump parliament) | |

| Constitution | |

| Frankfurt Constitution | |

The session was held from 18 May 1848 to 30 May 1849 in the Paulskirche at Frankfurt am Main.[3] Its existence was both part of and the result of the "March Revolution" within the states of the German Confederation.

After long and controversial debates, the assembly produced the so-called Frankfurt Constitution (Paulskirchenverfassung or St. Paul's Church Constitution, officially the Verfassung des Deutschen Reiches) which proclaimed a German Empire based on the principles of parliamentary democracy. This constitution fulfilled the main demands of the liberal and nationalist movements of the Vormärz and provided a foundation of basic rights, both of which stood in opposition to Metternich's system of Restoration. The parliament also proposed a constitutional monarchy headed by a hereditary emperor (Kaiser).

The Prussian king Frederick William IV refused to accept the office of "Emperor of the Germans" when it was offered to him on the grounds that such a constitution and such an offer were an abridgment of the rights of the princes of the individual German states. In the 20th century, however, major elements of the Frankfurt constitution became models for the Weimar Constitution of 1919 and the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany of 1949.

Background

editNapoleonic upheavals and German Confederation

editIn 1806, the Emperor Francis II had relinquished the crown of the Holy Roman Empire and dissolved the Empire. This was the result of the Napoleonic Wars and of direct military pressure from Napoléon Bonaparte.

After the victory of Prussia, the United Kingdom, Imperial Russia, and other states over Napoléon in 1815, the Congress of Vienna created the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund). The Austrian Empire dominated this system of loosely connected, independent states, but the system failed to account for the rising influence of Prussia. After the so-called "Wars of Liberation" (Befreiungskriege, the German term for the German part of the War of the Sixth Coalition), many contemporaries had expected a nation-state solution and thus considered the subdivision of Germany as unsatisfactory.

Apart from this nationalist component, calls for civic rights influenced political discourse. The Napoleonic Code Civil had led to the introduction of civic rights in some German states in the early 19th century. Furthermore, some German states had adopted constitutions after the foundation of the German Confederacy. Between 1819 and 1830, the Carlsbad Decrees and other instances of Restoration politics limited such developments. The unrest that resulted from the 1830 French July Revolution led to a temporary reversal of that trend, but after the demonstration for civic rights and national unity at the 1832 Hambach Festival, and the abortive attempt at an armed rising in the 1833 Frankfurter Wachensturm, the pressure on representatives of constitutional or democratic ideas was raised through measures such as censorship and bans on public assemblies.

The 1840s

editThe 1840s began with the Rhine Crisis, a primarily diplomatic scandal caused by the threat from the French prime minister Adolphe Thiers to invade Germany in a dispute between Paris and the four other Great Powers (including Austria and Prussia) over the Middle East. The threat alarmed the German Confederate Diet (Bundesversammlung), which was made up of representatives of the individual princes, and the only institution representing the whole German Confederation. The Diet voted to extend the Fortresses of the German Confederation (Bundesfestungen) at Mainz, Ulm, and Rastatt, while the Kingdom of Bavaria developed the fortress at Germersheim. Patriotic feelings of the public were effectively captured in the poem Die Wacht am Rhein (Watch on the Rhine) by Max Schneckenburger, and in songs such as "Der Deutsche Rhein" and the "Lied der Deutschen", the national anthem of Germany since 1922.

The mid-1840s saw an increased frequency of internal crises. This was partially the result of large-scale political developments, such as the escalation of the Schleswig-Holstein Question and the erection of the Bundesfestungen. Additionally, a series of bad harvests in parts of Germany, notably the southwest, led to widely spread famine-related unrest in 1845 and 1846. The changes caused by the beginnings of industrialization exacerbated social and economic tensions considerably, especially in Saxony and Silesia.

Meanwhile in the reform-oriented states, such as Baden, the development of a lively scene of Vereine (clubs or voluntary associations) provided an organizational framework for democratic, or popular, opposition. Especially in Southwest Germany, censorship could not effectively suppress the press. At such rallies as the Offenburg Popular Assembly of September 1847, radical democrat was called to overthrow the status quo. At the same time, the bourgeois opposition had increased its networking activities and began coordinating its activities in the individual chamber parliaments more and more confidently. Thus, at the Heppenheim Conference on 10 October 1847, eighteen liberal members from a variety of German states met to discuss common motions for a German nation-state.[4]

In Prussia, King Frederick William IV finally approved the assembly of a United Diet promised by his father in the decree of 22 May 1815. This body was commanded to debate and vote only on taxes and loans. However, as soon as it opened in April 1847, its members began discussions of press freedoms, voting, and human rights, the power to introduce legislation and foreign policy. After eleven weeks, the United Diet rejected a loan request. The King closed the diet in disgust and refused to say when it would be reopened. However, the people's enthusiasm for the United Diet was undeniable, and it was clear that a new political age was dawning. Many of the most eloquent members of the United Diet would play important roles in the future Frankfurt Parliament.[5]

Between 1846 and 1848, broader European developments aggravated this tension. The Peasant Uprising in Galicia in February and March 1846 was a revolt against serfdom, directed against manorial property and social oppression.[6] Rioting Galician peasants killed some 1,000 noblemen and destroyed about 500 manors.[7] Despite its failure, the uprising was seen by some scholars, including Karl Marx, as a "deeply democratic movement that aimed at land reform and other pressing social questions."[8] The uprising was praised by Marx and Friedrich Engels for being "the first in Europe to plant the banner of social revolution", and seen as a precursor to the coming Spring of Nations.[8][9] At the same time, the suppression of the Free City of Cracow in the midst of the uprising aroused the emotions of nationalists in Germany as much as in Poland.

In Switzerland, the Sonderbund War of November 1847 saw the swift defeat of the conservative Catholic cantons and victory for the radical left-wing in the Protestant cantons. Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich had pondered military intervention and later regretted not doing so, blaming the resulting waves of revolution on the Swiss.

Three months later, revolutionary workers and students in France deposed the Citizen King Louis-Philippe I in the February Revolution; their action resulted in the declaration of the Second Republic. In many European states, the resistance against Restoration policies increased and led to revolutionary unrest. In several parts of the Austrian Empire, namely in Hungary, Bohemia, Romania, and throughout Italy, in particular in Sicily, Rome, and Northern Italy, there were bloody revolts, replete with calls for local or regional autonomy and even for national independence.

Friedrich Daniel Bassermann, a liberal deputy in the second chamber of the parliament of Baden, helped to trigger the final impulse for the election of a pan-German assembly (or parliament). On 12 February 1848, referring to his own motion (Motion Bassermann) in 1844 and a comparable one by Carl Theodor Welcker in 1831, he called for a representation, elected by the people, in the Confederate Diet. Two weeks later, news of the successful revolution in France fanned the flames of the revolutionary mood. The revolution on German soil began in Baden, with the occupation of the Ständehaus at Karlsruhe. This was followed in April by the Heckerzug (named after its leader, Friedrich Hecker), the first of three revolutionary risings in the Grand Duchy. Within a few days and weeks, the revolts spread to the other German states.

The March Revolution

editThe central demands of the German opposition(s) were the granting of basic and civic rights regardless of property requirements, the appointment of liberal governments in the individual states and most importantly the creation of a German nation-state, with a pan-German constitution and a popular assembly. On 5 March 1848, opposition politicians and state deputies met at the Heidelberg Assembly to discuss these issues. They resolved to form a pre-parliament (Vorparlament), which was to prepare the elections for a national constitutional assembly. They also elected a "Committee of Seven" (Siebenerausschuss), which proceeded to invite 500 individuals to Frankfurt.

This development was accompanied and supported since early March by protest rallies and risings in many German states, including Baden, the Kingdom of Bavaria, the Kingdom of Saxony, the Kingdom of Württemberg, Austria and Prussia. Under such pressure, the individual princes recalled the existing conservative governments and replaced them with more liberal committees, the so-called "March Governments" (Märzregierungen). On 10 March 1848, the Bundestag of the German Confederation appointed a "Committee of Seventeen" (Siebzehnerausschuss) to prepare a draft constitution; on 20 March, the Bundestag urged the states of the confederation to call elections for a constitutional assembly. After bloody street fights (Barrikadenaufstand) in Prussia, a Prussian National Assembly was also convened, with the task of preparing a constitution for that kingdom.

The Pre-Parliament

editThe Pre-Parliament (Vorparlament) was in session at the St. Paul's Church, Frankfurt am Main (Paulskirche) in Frankfurt from 31 March to 3 April, chaired by Carl Joseph Anton Mittermaier. With the support of the moderate liberals, and against the opposition of the radical democrats, it decided to cooperate with the German Confederate Diet (Bundestag), to form a national constitutional assembly which would write a new constitution. For the transitional period until the actual formation of that assembly, the Vorparlament formed the Committee of Fifty (Fünfzigerausschuss), as a representation to face the German Confederation.

Though the pre-parliament had decided on 13 May 1848 for the opening of the National Assembly, the date was pushed to 18 May so that deputies from Prussia's outer provinces, which had only recently joined the Confederation, could arrive in time. By this calculation, the number of Prussian deputies to parliament was increased.[10]

Preparing for the Elections

editAccording to the pre-parliament's rules for elections, one deputy was to be seated for every 50,000 inhabitants within the Confederation, totaling some 649 jurisdictions (see this list of deputies at the opening of the parliament or list of all deputies on German Wikipedia).

The actual elections to the National Assembly depended on the laws of the individual states, which varied considerably. Württemberg, Holstein, the Electorate of Hesse (Hesse-Kassel) and the four remaining free cities (Hamburg, Lübeck, Bremen and Frankfurt) held direct elections. Most states chose an indirect procedure, usually involving a first round, voting to constitute an Electoral college which chose the actual deputies in a second round. There also were different arrangements regarding the right to vote, as the Frankfurt guidelines only stipulated that voters should be independent (selbständig) adult males. The definition of independence was handled differently from state to state and was frequently the subject of vociferous protests. Usually, it was interpreted to exclude the recipients of any poverty-related support, but in some areas, it also barred any person who did not have a household of their own, including apprentices living at their masters' homes. Even with restrictions, however, it is estimated that about 85% of the male population could vote. In Prussia, the definition used would have pushed this up to 90%, whereas the laws were much more restrictive in Saxony, Baden, and Hanover. The boycott in Austria's Czech majority areas and complications in Tiengen (Baden), (where the leader of the Heckerzug rebellion, Freidrich Hecker, in exile in Switzerland, was elected in two rounds) caused disruptions.

Organisation of the Nationalversammlung

editOn 18 May 1848, 379 deputies assembled in the Kaisersaal and walked solemnly to the Paulskirche to hold the first session of the German national assembly, under its chairman (by seniority) Friedrich Lang. Heinrich von Gagern, one of the best-known liberals throughout Germany, was elected president of the parliament. (See this List of deputies that attended the opening of the parliament.)

Assembly in the St. Paul's Church

editThe evangelical community of Frankfurt provided St. Paul's Church (Paulskirche) to the Pre-Parliament, which in turn became the home of the National Assembly. The altar was removed and a lectern was put in place for the presidium and the speaker, while the church organ was hidden by the large painting Germania. On either side of the gallery was the library. Despite its large capacity, which allowed the sitting of 600 deputies and a gallery for 2,000 spectators, there were some disadvantages. St. Paul's Church had extremely narrow corridors between the rows of seats in the central hall, and there were no rooms for consultation by the committees. The gallery attendees quickly became famous for their noise during the debates, which the more eloquent deputies learned to abuse to gain applause for themselves or raucous blame upon their enemies.

Form and Function of the Parliament

editThe Committee of Fifty that emerged from the Pre-parliament could have drafted Rules of Procedure for the National Assembly but rejected doing so on 29 April 1848. Therefore, Robert Mohl worked out his draft with two other deputies. The draft was completed on 10 May and adopted as regulation at the first sitting of the Parliament on 18 May. A commission was set up to draft the definitive rules of procedure on 29 May, which was adopted following a short debate. Six sections with 49 paragraphs regulated the electoral test, the board and staff of the assembly, quorum (set at 200 deputies), the formation of committees, order of debate, and inputs and petitions.[11]

Among other things, the rules of procedure provided that the meetings were public but could be confidential under certain conditions. In the 15 committees, the subjects of negotiation were pre-deliberated. It was settled on how applications were to be handled (twenty votes were needed for the plenary presentation) and that the agenda was fixed by the President at the end of the previous session. Deputies spoke in the order in which they answered but with a change from opponents and supporters of the bill. Speaking time was unlimited. Twenty deputies together could request the conclusion of a debate, at which the decision was then in plenary. There were no seating arrangements, but the deputies soon arranged themselves according to their political affiliations, from left and right.

By formal change or simple use, the Rules of Procedure could be modified. Political factions largely determined the speakers in a debate. A name roll call had to take place if at least fifty deputies demanded it; Speaker Friedrich Bassermann wanted to allow this only when needed because of uncertainty over the vote, but opponents saw in the roll call a means of documenting how the deputies voted. Finally, to save time, on 17 October 1848 voting cards were introduced (white "yes", blue "no") as a means of true documentation.

By the Rules of Procedure, an absolute majority of deputies present elected the President and the two Vice-Presidents of the National Assembly. A new election of officers was held every four weeks, as Robert von Mohl had suggested. The President maintained order in the session, set the agenda, and led the meeting. The overall board also included eight secretaries, who were jointly elected by a relative majority for the entire term. A panel of twelve stenographers wrote down all discussions in every session and withdrew in the evening to compare notes. They were assisted by 13 clerks. Final copies of the daily sessions were printed for the public two or three days later, though by the time of the Rump Parliament, printings were up to ten days late. Furthermore, the staff consisted of messengers and servants.

Presidents of the National Assembly

edit- Friedrich Lang as president by seniority (18 May 1848 until 19 May 1848)

- Heinrich von Gagern (19 May 1848 until 16 December 1848)

- Eduard Simson (18 December 1848 until 11 May 1849)

- Theodor Reh (12 May 1849 until 30 May 1849)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Löwe as president of the Stuttgart rump parliament (6 June 1849 until 18 June 1849)

Calculating the number of deputies

editThe Pre-Parliament had set the ratio of one deputy to the National Assembly per 50,000 inhabitants of the German Confederation, totaling 649 deputies. However, Czech-majority constituencies in Bohemia and Moravia boycotted the election, reducing the total to 585. As many deputies held multiple assignments in state parliaments or government offices, this reduced the average daily attendance to between 400 and 450 members. For important ballots, up to 540 deputies might attend to cast their vote. In April 1849, there were on average 436 deputies each sitting before the Austrian deputies were recalled (see below).[12]

Because of resignations and replacements, the total number of deputies who served between 18 May 1848 and 17 June 1849 has never been determined satisfactorily. Historian Jörg-Detlef Kühne counted a total of 799 deputies,[13] while Thomas Nipperdey reckoned a high figure of 830.[14] In the middle, Wolfram Siemann counted 812 deputies and Christian Jansen 809, which are the most popular figures.[15][16] The discrepancy may be due to the chaotic conditions of the elections, where disputes over constituencies and the conduct of the elections caused the late sitting of some deputies. Adjustments to the Demarkationslinie in the Grand Duchy of Posen created new constituencies and new deputies as late as February 1849 (see below). Finally, the passage of the Austrian Constitution in March 1849 convinced a few Czech deputies who had boycotted the National Assembly to appear, if only in moral opposition. For these reasons, the total number of deputies may never be settled.

Social background of the deputies

editThe social makeup of the deputies was very homogeneous throughout the session. The parliament mostly represented the educated bourgeoisie. 95% of deputies had the abitur, more than three-quarters had been to university, half of which had studied jurisprudence.[17] A considerable number of deputies were members of a Corps or a Burschenschaft. In terms of profession, upper-level civil servants formed the majority: this group included a total of 436 deputies, including 49 university lecturers or professors, 110 judges or prosecutors, and 115 high administrative clerks and district administrators (Landräte).[18] Due to their oppositional views, many of them had already conflicted with their princes for several years, including professors such as Jacob Grimm, Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann, Georg Gottfried Gervinus and Wilhelm Eduard Albrecht (all counted among the Göttingen Seven), and politicians such as Welcker and Itzstein who had been champions of constitutional rights for two decades. Among the professors, besides lawyers, experts in German Studies and historians were especially common, because under the sway of restoration politics, academic meetings in such disciplines, e.g. the Germanisten-Tage of 1846 and 1847, were often the only occasions where national themes could be discussed freely. Apart from those mentioned above, the academic Ernst Moritz Arndt, Johann Gustav Droysen, Carl Jaup, Friedrich Theodor Vischer, Bruno Hildebrand and Georg Waitz are especially notable.

Because of this composition, the National Assembly was later often dismissively dubbed the Professorenparlament ("Professors' parliament") and ridiculed with verses such as "Dreimal 100 Advokaten – Vaterland, du bist verraten; dreimal 100 Professoren – Vaterland, du bist verloren!"[19] "Three times 100 lawyers – Fatherland, you are betrayed; three times 100 professors – Fatherland, you are doomed".

149 deputies were self-employed bourgeois professionals, such as lawyers, doctors, journalists or clergymen, including well-known politicians such as Alexander von Soiron, Johann Jacoby, Karl Mathy, Johann Gustav Heckscher, Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler and Wilhelm Murschel.

The economically active middle class was represented by only about 60 deputies, including many publishers, including Bassermann and Georg Friedrich Kolb, but also businessmen, industrialists and bankers, such as Hermann Henrich Meier, Ernst Merck, Hermann von Beckerath, Gustav Mevissen and Carl Mez.

Tradesmen and representatives of agriculture were very poorly represented – the latter were mostly represented by big landowners from east of the Elbe, accompanied by only three farmers. Craftsmen like Robert Blum or Wilhelm Wolff were associated almost exclusively with the radical democratic Left, as they knew the social problems of the underprivileged classes from personal observations. A few of them, e.g. Wolff already saw themselves as explicit socialists.

A further striking aspect is the large number of well-known writers among the deputies, including Anastasius Grün, Johann Ludwig Uhland, Heinrich Laube and Victor Scheffel.

Factions and committees

editIn his opening speech on 19 May 1848, Gagern defined the main tasks of the national assembly as the creation of a "constitution for Germany" and the achievement of German unification. This was followed by a total of 230 sessions, supported by 26 committees and five commissions, in the course of which the deputies developed the Frankfurt Constitution.

While the opening session had generally been quite chaotic, with the deputies seated haphazardly, independent of their political affiliations, ordered parliamentary procedures developed quickly. Soon, deputies started assembling in Klubs (clubs), which served as discussion groups for kindred spirits and led to the development of Fraktionen (Parliamentary groups or factions), a necessary prerequisite for the development of political majorities. These Fraktionen were perceived as clubs and thus usually named after the location of their meetings; generally, they were quite unstable. According to their stances, especially on the constitution, the powers of parliament, and central government as opposed to individual states, they are broadly divided into three basic camps:

- The democratic left (demokratische Linke)—also called the "Ganzen" ("the whole ones") in contemporary jargon—consisting of the extreme and the moderate left (the Deutscher Hof group and its later split-offs Donnersberg, Nürnberger Hof and Westendhall).

- The liberal center—the so-called "Halben" ("Halves")—consisting of the left and right center (the right-wing liberal Casino and the left-wing liberal Württemberger Hof, and the later split-offs Augsburger Hof, Landsberg and Pariser Hof).

- The conservative right, composed of Protestants and conservatives (first Steinernes Haus, later Café Milani).

The largest groupings in numerical terms were the Casino, the Württemberger Hof, and beginning in 1849 the combined left, appearing as the Centralmärzverein ("Central March Club").

In his memoirs, the deputy Robert von Mohl wrote about the formation and functioning of the Clubs:

that originally there were four different clubs, based on the basic political orientations [...] Regarding the most important major questions, for example about Austria's participation and the election of emperors, the usual club-based divisions could be abandoned temporarily to create larger overall groups, such as the United Left, the Greater Germans in Hotel Schröder, the Imperials in Hotel Weidenbusch. These party meetings were indeed an important part of political life in Frankfurt, significant for positive, but also for negative, results. A club offered a get-together with politically kindred spirits, some of whom became true friends, comparably rapid decisions, and, as a result, perhaps success in the overall assembly.[20]

Provisional central power

editSince the national assembly had not been initiated by the German Confederation, it was lacking not only major constitutional bodies, such as a head of state and a government, but also legal legitimation. A modification of the Bundesakte, the constitution of the German Confederation could have brought about such legitimation, but was practically impossible to achieve, as it would have required the unanimous support of all 38 signatory states. Partially for this reason, influential European powers, including France and Russia, declined to recognize the Parliament. While the left demanded to solve this situation by creating a revolutionary parliamentary government, the center and right acted to create a monarchy.

Formation of the Central Power

editOn 24 June 1848, Heinrich von Gagern argued for a regency and provisional central government to carry out parliamentary decisions. On 28 June 1848, the Paulskirche parliament voted, with 450 votes against 100, for the so-called Provisional Central Power (Provisorische Zentralgewalt). The next day, 29 June, the Parliament cast votes for candidates to be the Reichsverweser or Regent of the Empire, a temporary head of state.[21] In the final tally, Archduke John of Austria gained 436 votes, Heinrich von Gagern received 52 votes, John Adam von Itzstein got 32 votes, and Archduke Stephen, Palatine of Hungary only 1 vote. The office of Regent was declared "irresponsible", meaning the Regent could not govern except through his ministers, who were responsible to the Parliament.

The Parliament then dispatched a deputation to the Archduke to present the honor bestowed upon him. However, the Confederate Diet (Bundesversammlung) sent their own letter, which the Archduke received prior to the parliamentary deputation, informing him that the princes of the Confederation had nominated him Regent before the Parliament had done so.[22] The implication was that the Regent should receive his power from the princes rather than the revolutionaries, but the practical effect of this power was yet to be seen.

The Archduke received the delegation on 5 July 1848 and accepted the position, stating, however, that he could not undertake full responsibility in Frankfurt until he had finished his current work of opening the Austrian Parliament in Vienna. Therefore, Archduke John drove to Frankfurt where he was sworn in as Regent on the morning of 12 July 1848 in the Paulskirche, and then crossed over to the Thurn and Taxis Palace to deliver a speech to the Confederate Diet, which then declared the end of its work and delegated its responsibilities to the Regent. Archduke John returned to Vienna on 17 July to finish his tasks there.

Practical tasks of the Provisional Central Power

editThe practical tasks of the Provisional Central Power were performed by a cabinet, consisting of a college of ministers under the leadership of a prime minister (Ministerpräsident). At the same time, the Provisional Central Power undertook to create a government apparatus, made up of specialized ministries and special envoys, employing, for financial reasons, mainly deputies of the assembly. The goal was to have a functional administration in place at the time of the Constitution's passage. Whatever form the final government of united Germany was to take would be defined by the Constitution, and necessary changes to the Provisional Central Power would be made accordingly. Significantly, the terms of the Regent's service explicitly forbade him or his ministers from interfering in the formulation of the Constitution.

On 15 July 1848, the Regent appointed his first government under prime minister Prince Carl zu Leiningen, the maternal half-brother of Queen Victoria of Great Britain. Ministers of the Interior, Justice, War, and Foreign Affairs were appointed on the same day, while Ministers for Finance and Trade were appointed on 5 August.

At the end of August 1848, there were a total of 26 persons employed in the administration of the provisional government. By 15 February 1849, the number had increased to 105. Some 35 of them worked in the War Department and had been employed by the Confederate Diet in the same capacity. The Ministry of Commerce employed 25 staff, including the section in charge of the German Fleet, which was only separated as an independent Naval ministry in May 1849. The diplomatic section employed mostly freelance personnel who held portfolios for state governments.

Prime Ministers of the Provisional Government

edit- Anton von Schmerling (15 July 1848 until 5 August 1848)

- Carl zu Leiningen (5. August 1848 until 5 September 1848)

- Anton von Schmerling (24 September 1848 until 15 December 1848)

- Heinrich von Gagern (17 December 1848 until 10 May 1849)

- Maximilian Grävell (16 May 1849 until 3 June 1849)

- August Ludwig zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg (3 June 1849 to 20 December 1849)

Relations with the National Assembly

editAs the National Assembly had initiated the creation of the Provisional Central Power, the Regent, and his government were expected to be subservient to their whims. Theoretically, the transfer of the Confederate Diet's authority to the Regent on 12 July gave him legitimate, binding power independent of the National Assembly. The Diet's rules regarding unanimous decision-making and a liberum veto had been a source of weakness when divided among 39 members. But, when concentrated in the hands of one man, it could make him supreme if he chose to be so.[23]

However, the Regent was a man of advanced age who was convinced, like most of his contemporaries, that his office would be of short duration and his role should be strictly an honor. Therefore, the personalities of the Prime Ministers during the life of the Provisional Central Power clearly defined the government during their tenures. Carl zu Leiningen was staunchly anti-Prussian and essentially anti-prince. His family had been mediatized along with hundreds of other nobles in the Napoleonic period, and he expected the remaining princes of Germany to set aside their crowns as well.[24] Anton von Schmerling held contempt for many of the institutions he had dutifully served, such as the Confederate Diet, and considered the National Assembly and his administration to be the future of Germany. Yet, as the National Assembly dragged out its work on the Constitution, the role of the Provisional Central Power changed. Soon, its purpose was to shore up the diminishing legitimacy of the whole project in the eyes of the people and the princes. Heinrich Gagern's appointment as Prime Minister in December was to serve that purpose, even though relations between the Regent and the former President of the National Assembly were poor.

After the Constitution was rejected by the larger states in April 1849, Gagern came into conflict with the Regent over his refusal to defend the Constitution and resigned.[25] (See Provisional Rump Parliament and Dissolution for the conflict between the Provisional Central Power and the National Assembly, and Aftermath for the period following.)

Main political issues

editSchleswig-Holstein Question and development of political camps

editInfluenced by the general nationalist atmosphere, the political situation in Schleswig and Holstein became especially explosive. According to the 1460 Treaty of Ribe, the two duchies were to remain eternally undivided and stood in personal union with Denmark. Nonetheless, only Holstein was part of the German Confederation, whereas Schleswig, with a mixed population of German-speakers and Danish speakers, formed a Danish fiefdom. German national liberals and the left demanded that Schleswig be admitted to the German Confederation and be represented at the national assembly, while Danish national liberals wanted to incorporate Schleswig into a new Danish national state. When King Frederick VII announced on 27 March 1848 the promulgation of a liberal constitution under which the duchy, while preserving its local autonomy, would become an integral part of Denmark, the radicals broke into revolt. The Estates of Holstein followed suit. A revolutionary government for the duchies was declared, and an army was hastily formed.

Opening hostilities

editDenmark landed 7,000 troops near Flensburg on 1 April 1848 to suppress the rebels. The Confederate Diet ordered Prussia to protect the duchies on 4 April and recognized the revolutionary government. But it was only when Denmark ordered its fleet to seize Prussian ships on 19 April that General Friedrich von Wrangel marched his Prussian troops against Danish positions at the Dannevirke entrenchment and the city of Schleswig. His columns pushed through Schleswig and seized the key fortress of Fredericia without a struggle on 2 May.[26] All of Jutland lay before Wrangel and the National Assembly urged a swift defeat of the Danes for the sake of Schleswig's revolution. But pressure from foreign sources arose from all quarters: Nicholas I of Russia sent sharp warnings to Berlin about respecting the integrity of Denmark, as King Frederick was a cousin of the Tsar. The British were agitated by Prussian aggression. Then, Sweden landed 6,000 troops on the Island of Funen opposite the Duchy of Schleswig.

Arranging an armistice

editWith Prussia threatened by war on several fronts, terms for an armistice were arranged through Swedish mediation at Malmö on 2 July 1848 and the order to cease operations handed to General Wrangel ten days later. However, Wrangel refused to accept the terms, declaring he was under orders not from Berlin but from the Confederate Diet, which had just been superseded by the Provisional Central Power. Therefore, he would hold positions and await further orders from the Regent. With popular sentiment on Wrangel's side, the Berlin court could not condemn him. They tried to steer a middle course by recognizing Wrangel's actions but asked the Regent for direct control of the German Federal Army in order to enforce a peace based on 2 July agreement. The Regent approved, but added extra demands upon the Danes and ordered the 30,000-strong German Confederate VIII. Army Corps to support Wrangel. This infuriated the foreign powers, who dispatched further threats to Berlin.

On 26 August, Prussia, under strong pressure from Britain, Russia, and Sweden, signed a six-month armistice with Denmark at Malmö. Its terms included the withdrawal of all German Confederate soldiers from Schleswig-Holstein and a shared administration of the land. No recognition was made of the Provisional Central Power in the deliberations.

On 5 September, at Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann's instigation, the National Assembly initially rejected the Malmö Armistice with a vote of 238 against 221. After that, Prime Minister Leiningen resigned his office. The Regent entrusted Dahlmann to form a new ministry, but his fiery rhetoric over Schleswig-Holstein could not be turned into political capital. The Austrian deputy Anton von Schmerling succeeded Leiningen as Prime Minister.

The Septemberunruhen

editIn a second vote, on 16 September 1848, the Assembly accepted the de facto position and approved the armistice with a narrow majority. In Frankfurt this led to the Septemberunruhen ("September unrest"), a popular rising that entailed the murder of parliamentarians from the Casino faction, Lichnowsky and Auerswald. The Regent was forced to call for the support of Prussian and Austrian troops stationed in the Fortress of Mainz, and these restored order in Frankfurt and the vicinity within two weeks.

Henceforth, the radical democrats, whose views were both leftist and nationalist, ceased to accept their representation through the National Assembly. In several states of the German Confederation, they resorted to individual revolutionary activities. For example, on 21 September, Gustav Struve declared a German republic at Lörrach, thus starting the second democratic rising in Baden. The nationalist unrest in Hungary spread to Vienna in early October, leading to a third revolutionary wave, the Wiener Oktoberaufstand ("Vienna October rising"), which further impeded the work of the Assembly.

Thus, the acceptance of the Treaty of Malmö marks the latest possible date of the final breach of cooperation between the liberal and the radical democratic camps. Radical democratic politicians saw it as final confirmation that the bourgeois politicians, as Hecker had said in spring 1848, "negotiate with the princes" instead of "acting in the name of the sovereign people",[27] thus becoming traitors to the cause of the people. In contrast, the bourgeois liberals saw the unrests as further proof for what they saw as the short-sighted and irresponsible stance of the left, and of the dangers of a "left-wing mob" spreading anarchy and murder. This early divide of its main components was of major importance for the later failure of the National Assembly, as it caused lasting damage not only to the esteem and acceptance of the parliament, but also to the cooperation among its factions.

The German Reichsflotte and financial problems

editDenmark's blockade of the North German coast caused deputies of National Assembly to call for the creation of the Reichsflotte or Imperial Fleet. The vote passed overwhelmingly on 14 June 1848, and this date is still celebrated as the foundation of the modern German Navy. However, the National Assembly had no funds to disburse for the project. National enthusiasm led to numerous penny-collections across Germany, as well the raising of volunteers to man whatever vessels could be purchased, to be commanded by retired naval officers from coastal German states.

Actual monies for the Navy did not become available until the Confederate Diet dissolved itself on 12 July 1848 and the Federal Fortress budget (Bundesmatrikularkasse) came into possession of the Provisional Central Power. The Regent then appointed the Bremen senator Arnold Duckwitz as Minister of the Marine (Minister für Marineangelegenheiten) to develop a war fleet with Prince Adalbert of Prussia as Commander in Chief and Karl Brommy as Chief of Operations. Difficulties arose in the procurement and equipment of suitable warships, as the British and Dutch were wary of a new naval power arising in the North Sea, and Denmark pressed its blockade harder. Furthermore, most German states forbade their trained personnel from serving in another navy, even though it was to be for their own common defense.

Nevertheless, by 15 October 1848, three steam corvettes and one sailing frigate were placed into service. In total, two sailing frigates, two steam regattas, six steam corvettes, 26 rowing gunboats, and one hawk ship were procured from diverse places.

In consequence, however, the entire budget inherited from the Confederate Diet was spent. Discussions in the National Assembly for raising funds through taxes were tied into the Constitutional debates, and the Provisional Central Power could not convince the state governments to make any more contributions than what they had agreed upon in the Confederate Diet. Even worse, the chaotic finances of such states as Austria, which was fighting wars in Italy and Hungary and suppressing rebellions in Prague and Vienna, meant little or no payment was to be expected in the near future.

Effectively, the National Assembly and the Provisional Central Power were bankrupt and unable to undertake such rudimentary projects as paying salaries, purchasing buildings, or even publishing notices. The revolution functioned on the financial charity of individual Germans and the good will of the states, which grew thinner as the months passed.

The German army and rising confidence of the princes

editOn 12 July 1848, the Confederate Diet transferred responsibility for the German Confederate Army and the Federal Fortresses to the Provisional Central Power. The Regent appointed General Eduard von Peucker, Prussia's representative to the Federal Military Commission, as Minister of War.

Anxious to bring the war with Denmark to a victorious conclusion, on 15 July the National Assembly decreed that the German Confederate Army should be doubled in size. This was to be done by raising the proportion of recruits to 2 percent of the population, and also by the abolition of all laws of exemption in the individual States. Not only did the Prussian government complain about interference in its conduct of the Danish war, but the various Chambers of the States published complaints against the Parliament for violating their sovereignty and threatening their already shaky state budgets. Many common people also denounced the idea of an expanded army and conscription.

The military parade of 6 August

editOn 16 July, the Minister of War sent a circular to the state Governments with a proclamation to the German troops, in which he decreed the Regent as the highest military authority in Germany. At the same time, he ordered the state governments to call out the troops of every garrison for a parade on 6 August, the 42nd anniversary of the end of the Holy Roman Empire. Their commanding officers were to read Peucker's proclamation before them, after which the troops were to shout "Hurrah!" for the Regent three times. Then, the soldiers were to assume the German cockade as a symbol of their allegiance to the new order of things.

In Berlin, King Frederick William issued a decree to the army that on 6 August there was to be no parade anywhere in Prussia. In Vienna, Minister of War Theodore von Latour and the Ministerial Council were indignant at the presumption. Latour demanded a sharp response from the government of Austria, which at that moment was headed by Archduke John in Vienna. Ironically, the Archduke had to dispatch a complaint about the matter in the name of the Austrian government to himself as head of the Provisional Central Power.[28]

Thus, the attempt of the Provisional Central Power to assert its authority over all the armed forces within Germany failed. The Regent still held authority over the German Confederate Army, but this force represented less than half of the standing armies of the states, and these were led by officers whose loyalty remained first and foremost to their sovereign princes.

The Cologne cathedral festival

editOn 20 July the Regent, along with Heinrich Gagern and a large deputation from the Parliament, accepted an invitation by King Frederick William to take part in a festival celebrating new construction to the great Cologne Cathedral. The radical left condemned the festival, correctly assuming it would strengthen feelings of loyalty in the people toward their princes. On 15 August, the deputation arrived in Cologne by riverboat. Standing on the quay, the King embraced the Regent to the cheer of the crowds, and then allowed Gagern to present the members of the deputation. He addressed to them a few friendly words on the importance of their work and added with emphasis: "Do not forget that there are still Princes in Germany, and that I am one of them."[29]

Later, a torchlight parade carried the King and the Regent to the cathedral square, where the crowds showered them with adulation. Gagern, however, missed the parade entirely as it dispersed due to rains before it reached the end of the route where he awaited it. The National Assembly deputies marched in the parade only as one of many groups, flanked by fire-fighters and police. Finally, at the grand banquet afterward, a toast by prominent leftist deputy Franz Raveaux was missed by the royal retinue and other dignitaries, as all of them departed early.[30]

Taken together, these were glaring indications of the revolutionaries' lessening influence, whereas cheering crowds surrounding the King and Regent amplified the growing confidence of the princes.

Oktoberaufstand and execution of Blum

editThe Vienna Uprising at the beginning of October forced the Austrian court to flee the city. The National Assembly, instigated by left-wing deputies, attempted to mediate between the Austrian government and the revolutionaries. In the meantime, the Austrian army violently suppressed the rising. In the course of events, the deputy Robert Blum, one of the figureheads of the democratic left, was arrested. General Alfred von Windisch-Grätz ignored Blum's parliamentary immunity, tried him before a military tribunal, and had him executed by firing squad on 9 November 1848. This highlighted the powerlessness of the National Assembly and its dependence on the goodwill of the state governments of the German Confederation. In Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany (1852), Friedrich Engels wrote:

The fact that fate of the revolution was decided in Vienna and Berlin, that the key issues of life were dealt with in both those capitals without taking the slightest notice of the Frankfurt assembly—that fact alone is sufficient to prove that the institution was a mere debating club, consisting of an accumulation of gullible wretches who allowed themselves to be abused as puppets by the governments, so as to provide a show to amuse the shopkeepers and tradesmen of small states and towns, as long as it was considered necessary to distract their attention.[31]

The execution also indicated that the force of the March Revolution was beginning to flag by the autumn of 1848. This did not apply only to Austria. The power of the governments appointed in March was eroding. In Prussia, the Prussian National Assembly was disbanded and its draft constitution rejected.

Defining "Germany"

editWith history, politics, and ethnicity in conflict, defining the meaning of "Germany" was proving a major obstacle for the National Assembly. The biggest problem was that the two most powerful states, Prussia and especially Austria, had large possessions with non-German populations outside the boundaries of the Confederation. Incorporating such areas into a German nation-state not only raised questions regarding the national identity of the inhabitants, but also challenged the relationship between the two states within Germany. At the same time, Denmark and the Netherlands administered sovereign territories within the Confederation, further entangling the question of Germany in the affairs of foreign powers.

This problem was partially solved on 11 April 1848, when the Confederate Diet admitted Prussia's outer territories (the Province of Prussia and as-yet undefined "German areas" of the Grand Duchy of Posen) into the Confederation.[32] On the same day, Austria's Emperor Ferdinand I granted Hungary an independent ministry responsible to the Diet at Pesth, theoretically severing Hungary from Austria's German possessions.

Deputy Venedey addressed the "German Question" during a debate on 5 July 1848 in this way: "I am against any other expression, or against any other explanation, than every German... In France there are also many nationalities, but all know that they are French. There are also different nationalities in England, and yet all know that they are Englishmen. We want to start by saying that everyone is German. We should therefore also stand by the expression every German, and vote very soon, because if these words lead to weeks of negotiations, we never come to an end." In reply to that, deputy Titus Mareck of Graz quipped, "Try and say every German, and you will see if the Slavs in Styria and Bohemia will be satisfied with it. I can assure you that this expression will be properly interpreted by the Czechs and Slavic leaders."[33] Thus, the question proved too complicated to be answered after months of negotiations, much less weeks.

Schleswig

editThough the Duchy of Schleswig's situation was troublesome, its position within the new Germany was undisputed. The Confederate Diet welcomed the embattled duchy as its newest appendage on 12 April 1848.[34] The Vorparlement similarly decreed the union of Schleswig with the German state, and sent invitations for Schleswig deputies to participate in the upcoming National Assembly.[35]

Bohemia and Moravia

editBohemia and Moravia were already part of the Confederation, and without question were to remain within the new Germany, despite protests by the Czech population. Districts in the Czech majority areas boycotted elections to the National Assembly, and only a few Czech deputies took their seats in the Paulskirche. The Pan-Slav Congress begun in Prague on 2 June 1848 was cut short on 12 June by civil unrest, and the city was bombarded into submission by General Windisch-Grätz on 16 June. The National Assembly applauded the destruction of Slav secession, but some deputies saw in Windisch-Grätz's violence a warning of what might befall them in the future.

Posen and the Demarkationslinie

editSimilar to Bohemia, the National Assembly was determined to incorporate much of the Prussian Grand Duchy of Posen against the wishes of the majority Polish population, especially after the failed Greater Poland uprising which lasted from 20 March until 9 May. Three separate debates and votes (the first on 26 April 1848 in the Vorparlement, the next on 27 July, the last on 6 February 1849) demarcated the borderline (Demarkationslinie Posen) between the German areas to have representation in the National Assembly and the Polish areas to be excluded.[36][37][38] Each successive vote on the Demarkationslinie contracted the Polish area until only one-third of the province was excluded, while large a Polish population was to remain within the future German state.

Limburg

editDebates about the integration of the Duchy of Limburg into the new Germany strained otherwise good relations with King William II of the Netherlands. King William was also Grand Duke of Luxemburg, which was a member of the German Confederation. After the Belgian revolution was finally settled in 1839, Luxemburg ceded 60 percent of its territory to Belgium. As compensation, the Dutch province of Limburg became a member of the Confederation, although only that portion whose population equaled what was lost to Belgium. Thus, the cities of Maastricht and Venlo were excluded. Membership meant very little, as the administration of Limburg remained entirely Dutch and the population was Dutch in national sentiment. Nevertheless, the National Assembly held several debates over the fate of Limburg, which not only irritated King William but also the British and the French. The Limburg question was never solved during the life of the National Assembly.

Austrian Littoral and Trentino

editDespite their ethnic differences, the Italian-majority areas of the Austrian Littoral fully participated in the National Assembly. However, due to historical considerations, former Venetian possessions such as Monfalcone and half of Istria remained outside of the Confederation, and the question of their full integration into the new Germany was discussed. Most of the left-wing deputies had nationalist sentiments for the Italian revolutionaries in Milan and Venice and argued for a unified Italian state in the fashion of the new Germany being planned. However, there were few who approved of separating the littoral from the German Confederation, if only for strategic reasons.

In the Italian areas of Tyrol known as Trentino, the voting districts of Trient and Roveredo sent deputies to Frankfurt. In fact, the Roveredo municipal government petitioned the National Assembly to allow the Trentino to secede from the German Confederation.[39] In response, the Landtag of Tyrol dispatched a letter of protest to the National Assembly for accepting the petition.[40] The question of Istria's full admission into the Confederation, and Trentino's withdrawal, were referred to Committee but never voted upon in the Assembly itself.

Auschwitz and Zator

editThe two Austrian Duchies of Auschwitz and Zator joined the German Confederation in 1818 by virtue of their affiliation with Austrian Silesia,[41] but the question of whether they should be part of the new Germany was only discussed briefly in the National Assembly. The population was entirely Polish and the territories an integral part of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, itself outside of the Confederate boundaries. Deputy Carl Giskra of Mährisch-Trubau rhetorically asked how much longer the "German lands of Zator and Auschowitz" should remain part of Galicia,[42] but another deputy derisively referred to the territories as "fantasy duchies" and denounced the question even being raised.

Greater German or smaller German solution

editRegardless of these questions, the shape of the future German nation-state had only two real possibilities. The "Smaller German Solution" (Kleindeutsche Lösung) aimed for a Germany under the leadership of Prussia and excluded Imperial Austria so as to avoid becoming embroiled in the problems of that multi-cultural state. The supporters of the "Greater German Solution" (Großdeutsche Lösung), however, supported Austria's incorporation. Some of those deputies expected the integration of all the Habsburg monarchy's territories, while other Greater German supporters called for a variant only including areas settled by Germans within a German state.

The majority of the radical left voted for the Greater German variant, accepting the possibility formulated by Carl Vogt of a "holy war for western culture against the barbarism of the East",[43] i.e., against Poland and Hungary, whereas the liberal centre supported a more pragmatic stance. On 27 October 1848, the National Assembly voted for a Greater German Solution, but incorporating only "Austria's German lands".

Austria's protests

editThe court camarilla surrounding the incapacitated Austrian Emperor Ferdinand was not, however, willing to break up the state. On 27 November 1848, only a few days before the coronation of Ferdinand's designated successor, Franz Joseph I, Prime Minister Prince Felix zu Schwarzenberg declared the indivisibility of Austria. Thus, it became clear that, at most, the National Assembly could achieve national unity within the smaller German solution, with Prussia as the sole major power. Although Schwarzenberg demanded the incorporation of the whole of Austria into the new state once more in March 1849, the dice had fallen in favor of a Smaller German Empire by December 1848, when the irreconcilable differences between the position of Austria and that of the National Assembly had forced the Austrian, Schmerling, to resign from his role as Ministerpräsident of the provisional government. He was succeeded by Heinrich von Gagern.

Nonetheless, the Paulskirche Constitution was designed to allow a later accession of Austria, by referring to the territories of the German Confederation and formulating special arrangements for states with German and non-German areas. The allocation of votes in the Staatenhaus (§ 87 ) also allowed for a later Austrian entry.[44]

Drafting the Imperial Constitution

editThe National Assembly appointed a three-person committee of constitution on 24 May 1848, chaired by Bassermann and charged with preparing and coordinating the drafting of a Reichsverfassung ("Imperial Constitution"). It could make use of the preparatory work done by the Committee of Seventeen appointed earlier by the Confederate Diet.

Remarkably, the National Assembly did not begin its mandated work of drafting the Constitution until 19 October 1848. Up to that time, exactly five months after the opening of the National Assembly, the deputies had failed to move forward with its most important task. However, they were driven to urgency by the violent outbreak of the Vienna Uprising and its suppression by the Austrian Army.

Basic rights

editOn 28 December, the Assembly's press organ, the Reichsgesetzblatt published the Reichsgesetz betreffend die Grundrechte des deutschen Volkes ("Imperial law regarding the basic rights of the German people") of 27 December 1848, declaring the basic rights as immediately applicable.[45]

The catalogue of basic rights included Freedom of Movement, Equal Treatment for all Germans in all of Germany, the abolishment of class-based privileges and medieval burdens, Freedom of Religion, Freedom of Conscience, the abolishment of capital punishment, Freedom of Research and Education, Freedom of Assembly, basic rights in regard to police activity and judicial proceedings, the inviolability of the home, Freedom of the Press, independence of judges, Freedom of Trade and Freedom of establishment.

Qualifying the Emperor

editOn 23 January 1849, a resolution that one of the reigning German princes should be elected as Emperor of Germany was adopted with 258 votes against 211.[46] As the King of Prussia was implicitly the candidate, the vote saw conservative Austrian deputies joining the radical republican left in opposition.

The first and second readings

editThe first reading of the Constitution was completed on 3 February 1849. A list of amendments were proposed by 29 governments in common and on 15 February Gottfried Ludolf Camphausen, Prussia's representative to the National Assembly, handed the draft to Prime Minister Gagern, who forwarded it to the Committee of the Parliament that was preparing the Constitution for its second reading.[47] The amendments, designed to ensure the prerogatives of the princes in various state functions, were sidelined by arguments from the left for universal suffrage in elections and the secret ballot. Only two of Camphausen's amendments were discussed and no modifications made. Furthermore, passage of the Austrian Constitution on 4 March 1849 was used as an excuse by Prince Schwarzenberg to declare the first draft of the federal Constitution incompatible with Austrian law, and would therefore have to be scrapped and replaced by a more accommodating document. The proclamation shocked the National Assembly, resulting in floral speeches condemning "Austrian sabotage". But when on 21 March deputy Carl Theodor Welcker of Frankfurt brought up a motion to pass the Constitution "as is" to force the issue, it was rejected by 283 votes against 252.[48] Nevertheless, shows of resistance to their Constitutional work by so many of the states shook the confidence of many deputies. There was suddenly a desperation in the National Assembly to complete their work.

The second reading commenced on 23 March 1849 after agreements had been reached with the Center and the Left over procedure: It was to be read without interruption to the very end; every paragraph was to be voted upon as reported by the committee on the Constitution; amendments were to be considered only at the request of at least 50 deputies. The reading proceeded with unusual pace, as the deputies feared they would become illegitimate in public opinion unless they overcame mounting obstacles and produced the Constitution. The Center conceded an amendment on the last day, in the form of an extension of the suspensive veto, to cover changes in the Constitution. They warned it could be used to overthrow the Imperial system, to which the Left applauded. Austria's proposed amendment to turn the Imperial dignity into a Directory was soundly defeated, thus protecting the office of Emperor. The Left derided the center by shouting, "A German Emperor chosen by a majority of four votes from four faithless Austrians!" However, 91 Austrian deputies had cast votes for the Imperial system, thus rejecting Prince Schwarzenberg's interference.[49] An article to create an Imperial Council to advise the Emperor was stricken from the Constitution at the last moment.

Passage of the Constitution

editThe National Assembly passed the complete Imperial Constitution in the late afternoon of 27 March 1849. It was carried narrowly, by 267 against 263 votes. The version passed included the creation of a hereditary emperor (Erbkaisertum), which had been favoured mainly by the erbkaiserliche group around Gagern, with the reluctant support of the Westendhall group around Heinrich Simon.

The people were to be represented by a directly elected House of Commons (Volkshaus) and a House of the States (Staatenhaus) of representatives sent by the individual states. Half of each Staatenhaus delegation was to be appointed by the respective state government, the other by the state parliament.

Head of state and Kaiserdeputation

editAs the near-inevitable result of having chosen the Smaller German Solution and the constitutional monarchy as form of government, the Prussian king was elected as hereditary head of state on 28 March 1849. The vote was carried by 290 votes against 248 abstentions, embodying resistance primarily by all left-wing, southern German and Austrian deputies. The deputies knew that Frederick William IV held strong prejudices against the work of the Frankfurt Parliament, but on 23 January, the Prussian government had informed the states of the German Confederation that Prussia would accept the idea of a hereditary emperor.

Further, Prussia (unlike Bavaria, Württemberg, Saxony, and Hannover) had indicated its support of the draft constitution in a statement made after the first reading. Additionally, the representatives of the provisional government had attempted through innumerable meetings and talks to build an alliance with the Prussian government, especially by creating a common front against the radical left and by arguing that the monarchy could only survive if it accepted a constitutional-parliamentary system. The November 1848 discussion of Bassermann and Hergenhahn with the king also aimed in the same direction.

Shortly after the vote of 27 March 1849, Archduke John announced his resignation as Regent, explaining that the vote ended all reason for his office. President of the Assembly Eduard von Simson rushed to the Thurn and Taxis palace and pleaded for him to remain as Regent until the coronation could occur.

On 3 April 1849, the Kaiserdeputation ("Emperor Deputation"), a group of deputies chosen by the National Assembly and headed by Simson, offered Frederick William the office of Emperor. He gave an evasive answer, arguing that he could not accept the crown without the agreement of the princes and Free Cities. In reality, Frederick William believed in the principle of the Divine Right of Kings and thus did not want to accept a crown touched by "the hussy smell of revolution".[50] Then, on 5 April 1849, Prince Schwarzenberg recalled the Austrian deputies from the National Assembly and denounced the Constitution as being incompatible with Austrian sovereignty, with the caveat that Austria did not exclude itself from a German union, providing it was structured according to Austria's needs. To ensure Austria's role in German affairs did not diminish, Schwarzenberg convinced Archduke John to remain in office as Regent.

By 14 April 1849, 28 mostly petty states had accepted the constitution, and Württemberg was the only kingdom to do so after much hesitation.[51] The kings of Hanover, Saxony, and Bavaria awaited Prussia's formal response to the Constitution before decreeing their own. Then, on 21 April, King Frederick William IV formally rejected the Imperial Constitution and the crown that was to go with it.

This spelled the final failure of the National Assembly's constitution and thus of the German revolution. The rejection of the crown was understood by the other princes as a signal that the political scales had fully tipped against the liberals. Opinion even in autumn 1848 had it that the National Assembly had taken far too long to draft the Constitution. Had they accomplished their task in the summer and offered the crown in autumn, the revolution might have taken a different turn.

Rump parliament and dissolution

editOn 5 April 1849, all Austrian deputies left Frankfurt. The new elections called for by Prime Minister Heinrich Gagern did not take place, further weakening the assembly. In desperation, Gagern demanded that the Regent personally intervene with the Princes to save the Constitution. Reminding Gagern of his own terms forbidding the Provisional Central Power from interfering in the work of the Constitution, the Regent refused, and Gagern resigned in consequence on 10 May 1849.[25]

On 14 May, the Prussian parliamentarians also resigned their mandates. In the following week, nearly all conservative and bourgeois-liberal deputies left the parliament. The remaining left-wing forces insisted that 28 states had accepted the Frankfurt Constitution and began the Constitutional Campaign (Reichsverfassungskampagne), an all-out call for resistance against the Princes who refused to accept the Constitution. The supporters of the campaign did not consider themselves revolutionaries. From their perspective, they represented a legitimate national executive power acting against states that had breached the Constitution. Nonetheless, only the radical democratic left was willing to use force to support the Constitution, notwithstanding their original reservations against it. In view of their failure, the bourgeoisie and the leading liberal politicians of the faction of the Halbe ("half ones") rejected a renewed revolution and withdrew—most of them disappointed—from their hard work in the Frankfurt Parliament.

The May Uprisings

editIn the meantime, the Reichsverfassungskampagne had not achieved any success regarding acceptance of the Constitution, but had managed to mobilize those elements of the population that were willing to commit violent revolution. In Saxony, this led to the May Uprising in Dresden, in the Bavarian part of the Palatinate, the Pfälzer Aufstand, a rising during which revolutionaries gained the de facto governmental power. On 14 May, Leopold, Grand Duke of Baden had to flee the country after a mutiny of the Rastatt garrison. The insurrectionists declared a Baden Republic and formed a revolutionary government headed by the Paulskirche deputy Lorenz Brentano. Together with Baden soldiers that had joined their side, they formed an army under the leadership of the Polish general Mieroslawski.

Break with the Provisional Central Power

editThe Regent appointed the conservative Greater German advocate and National Assembly deputy Maximilian Grävell as his new Prime Minister on 16 May 1849. This so incensed the National Assembly that they held a vote of no confidence in the government on 17 May, resulting in a vote of 191 against 12 with 44 abstentions. Receiving moral support from Austria, the Regent stood defiant and retained his Prime Minister. Calls for the resignation of the Regent immediately followed.[52]

The next day, 18 May, Prime Minister Grävell ascended the speaker's podium in the Paulskirche and explained the Regent's motives for appointing him as Prime Minister, and the Regent's refusal to obey the National Assembly's decisions. Grävell stated, "You remember, gentlemen, that [the Regent] had declared to the deputation of the National Assembly which had been sent to him that he accepted the request made to him as a result of [all the German] governments' approval. You will recall that the Regent was introduced into his office in this place, but then the Confederate Diet ... gave him authority. The Regent, as a thoroughly conscientious man, will certainly never be able to lay down his office into any other hands than into those who have empowered him."

The uproar in the parliament was intense, yet Grävell persisted: "If you have patience to wait, I will explain. The Regent can and will only return his office to the National Assembly from which it originated. But he will do so and cannot do otherwise, except as a staunch steward of the power entrusted to him by the governments, and only to return this power back into the hands of the governments."

Great unrest answered Grävell's words, as the National Assembly was directly confronted with the statement that the Regent's power originated from the states, not the revolution. With insults and jeers raining down from the gallery, the Prime Minister further stated, "Gentlemen! Consider the consequences of the withdrawal of the Regent and the divorce of Germany from this war [with Denmark]. Remember that the honor of Germany is at stake!" Grävell finally concluded, "These, gentlemen, are the motives for why we came here, and why we cannot resign, in spite of your open distrust." The Prime Minister then departed. Deputy William Zimmermann of Stuttgart shouted from the gallery, "This is unheard of in the history of the world!"[53]

After reading the rules of the Provisional Central Power, adopted 28 June and 4 September 1848, especially articles that address the removal of ministers and the Regent, President Theodore Reh of the National Assembly read the report from the Committee of Thirty that drafted a provisional regency (Reichsregentschaft) to defend the Constitution. The vote passed with a majority (126 to 116 votes) for the plan with a provisional governor (Reichstatthalter) to replace the Regent. However, external events overtook the National Assembly before they could attempt to carry out their plan.

Removal of the National Assembly to Stuttgart

editAs German Confederate troops under orders from the Regent began to crush revolutionary outbreak in the Palatinate, the remaining deputies in the Free City of Frankfurt began to feel threatened. Further deputies that were not willing to align with radical democratic left resigned their mandates or gave them up when asked to by their home governments. On 26 May, the Frankfurt National Assembly had to lower its quorum to a mere hundred due to the enduring low presence of deputies. The remaining deputies decided to escape an approaching army of occupation by moving the parliament to Stuttgart in Württemberg on 31 May. This had been suggested by the deputy Friedrich von Römer, who was also prime minister and minister of justice of the Württemberg government. Essentially, the Frankfurt National Assembly was dissolved at this point. From 6 June 1849 onwards, the remaining 154 deputies met in Stuttgart under the presidency of Friedrich Wilhelm Löwe. This convention was dismissively called the Rump Parliament (Rumpfparlament).

The Provisional Regency and People's Army

editSince the Provisional Central Power and the Regent refused to acknowledge the new situation, the Rump Parliament declared both as dismissed and proclaimed a new provisional regency (Reichsregentschaft) led by five deputies Franz Raveaux, Carl Vogt, Heinrich Simon, Friedrich Schüler and August Becher, and fashioned after the Directory of the French First Republic. Following its view of itself as the legitimate German parliament, the rump parliament called for tax resistance and military resistance against those states that did not accept the Paulskirche Constitution. On 16 June 1849, the rump parliament declared the formation of a People's Army (Volkswehr) consisting of four classes from age 18 to 60. The Provisional Regency then called all Germans to arms in order to defend the Constitution of 1849.[54]

Since these actions challenged the authority of Württemberg, and the Prussian army was successfully crushing the rebellions in the nearby Baden and the Palatinate, Römer and the Württemberg government distanced themselves from the rump parliament and prepared for its dissolution.

Dissolution

editOn 17 June, Römer informed the president of the parliament that "the Württemberg government was no longer in a position to tolerate the meetings of the National Assembly that had moved to its territory, nor the activities of the regency elected on the 6th, anywhere in Stuttgart or Württemberg".[55] At this point, the rump parliament had only 99 deputies and did not reach a quorum according to its own rules. On 18 June, the Württemberg army occupied the parliamentary chamber before the session started. The deputies reacted by organizing an impromptu protest march which was promptly quashed by the soldiers without bloodshed. Those deputies that were not from Württemberg were expelled.

Subsequent plans to move the parliament (or what was left of it) to Karlsruhe in Baden could not be implemented due to the looming defeat of the Baden revolutionaries, which was completed five weeks later.

Aftermath

editAfter rejecting the Imperial Constitution on 21 April 1849, Prussia attempted to undermine the Provisional Central Power. King Frederick William IV intended to assume its functions after the Regent announced his resignation at the end of March. However, Prince Schwarzenberg had foiled Prussia's efforts to do so. Therefore, Prussia chose to support the Unionspolitik ("union policy") designed by the conservative Paulskirche deputy Joseph von Radowitz for a Smaller German Solution under Prussian leadership. This entailed modifying the Frankfurt Parliament's conclusions, with a stronger role for the Prussian hereditary monarch and imposed "from above". The National Assembly was notified of Prussia's intentions on 28 April. The deputies refused to consider changes to their Constitution, and Prince Schwarzenberg similarly rejected Prussia's proposals on 16 May. A draft dated 28 May 1849 created a league of the three kingdoms of Prussia, Hannover, and Saxony for one year in which to formulate an acceptable constitution for Germany.

The Erbkaiserliche around Gagern supported Prussia's policy in the Gotha Post-Parliament and the Erfurt Union Parliament. This policy was based on Prussia's insistence that both the National Assembly and the German Confederation were defunct. However, Austria's policy was that the German Confederation had never ceased to exist. Rather, only the Confederate Diet had dissolved itself on 12 July 1848. Therefore, the Austrian Emperor could be restored as President of the German Confederation in succession to the Regent.

With this in mind, Archduke John attempted to resign his office once more in August 1849, stating that the Regency should be jointly held by Prussia and Austria through a committee of four until 1 May 1850, by which time all of the German governments should have decided on a new Constitution. The two governments agreed in principle, and a so-called Compact of Interim was signed on 30 September, transferring all responsibilities of the Provisional Central Power to the two states, though not relieving the Regent of his office just yet. By signing this compact, Prussia tacitly accepted Austria's policy that the German Confederation still existed.[56]

One week later, disagreements between the three kingdoms saw Prussia's project for a new federal German government fall apart. On 5 October 1849, Hanover argued for an understanding with Austria before a new Parliament could be elected and a new Constitution drawn up, and Saxony seconded the motion. On 20 October, both kingdoms ended active participation in the league's deliberations, isolating Prussia entirely. With Austria's position in Germany more and more secure, Archduke John was finally permitted to resign his office of Regent on 20 December 1849.[57]

Prussia spent the next year defying Austria's protests. On 30 November 1850 the Punctuation of Olmütz forced Prussia to abandon its proposal to alter Germany's political composition in its favor. By that time, all of the states in Germany had suppressed their Constitutions, popularly elected parliaments, and democratic clubs, thus erasing all work of the revolution. An exception was in Austria, where the hated corvée unpaid labor was not revived after it had been abolished in May 1848.[58] On 30 May 1851, the old Confederate Diet was reopened in the Thurn and Taxis Palace.[59]

Long-term political effects

editThe March Revolution led to a major increase of Prussia's political importance, though only gradually. By permitting the revolution to consolidate itself, and by supporting the Schleswig-Holstein rebellion with Prussian troops, the Hohenzollern dynasty was reviled in Scandinavia and especially Russia. Prussia's role as a Great Power in Europe did not recover until the Crimean War saw Russia isolated, Austria maligned for its wavering policy, and Britain and France embarrassed by their poor military performance.