Germania is the name of a painting that was probably created in March 1848. It hung in the St. Paul's Church (Paulskirche) in Frankfurt, Germany. At that time, first the so-called Pre-Parliament and then the Frankfurt National Assembly, the first all-German parliament, met there. The National Assembly was a popular motif of the time, so the Germania painting also became very well-known. After the National Assembly was violently terminated in May 1849, the painting was taken down. In 1867 it was moved to the German National Museum in Nuremberg.

The painting is one of the best-known representations of Germania, a woman who stands for Germany. Such a national allegory also exists in other countries. The motif was often taken up during the time of the emerging German Empire 1848/1849 and later.[1]

Image contents

editThe early date of completion, at the end of March 1848, could explain the imagery used. At that time, there were still few ideas about the future of Germany and its form of government. Accordingly, the painting is politically restrained and refers neither to the popular movement nor to a crown (of a German emperor). It is clearly less militant than comparable paintings of the revolutionary period, more conservative-moderate and appealing to the unity of the nation.[2]

"Germania] stands on a stone pedestal high above a shadowy hilly landscape, illuminated in gold by the rising sun of a new age. She wears a red ermine-covered ruler's robe with the double-headed eagle in the breast shield, over it a wide, blue-lined gold brocade cloak. With her left hand she is leaning on a medieval tournament lance from which the black-red-gold flag is flying. The shimmering German tricolour forms the foil for the youthful blond head of Germania crowned with oak leaves. [...] In her right hand Germania holds a raised bare sword and an olive branch. At her feet lies a burst fetlock." (Rainer Schoch)[3]

"With shattered fetters, holding the black-red-gold flag in her left hand, she embodies the nation's awakening to freedom and self-confidence, and in the motif of the bare sword, but entwined with an olive branch, which Germania holds in her right hand, love of peace is combined with a fortitude that does not yet display the provocative, even militant streak of later Germania images." (Dieter Hein)[4]

Painter

editThe painting is traditionally attributed to Philipp Veit. He had already completed a depiction of Germania in 1836. This earlier Germania, however, is not standing but sitting and appears to be melancholic. It is to be seen as a retrospective reference to the Middle Ages, less as a combative symbol for the present. According to Rainer Schoch, the type and allegorical language of the Paulskirche painting is "obviously" based on Veit's 1836 painting.[5]

Around 1900, various individuals recorded in their memoirs that the Paulskirche painting had been made from a drawing by Veit. According to the son of Eduard von Steinle, a painter friend of Veit's from the Nazarene circle, his father had created the picture for St Paul's Church in a few days. This happened shortly after the election of the Reichsverweser (29 June 1848).

Friedrich Siegmund Jucho was the "custodian of the estate" of the National Assembly and the saviour of the constitutional document. According to him, the picture was "painted by local artists". The pre-parliament, a convention that discussed the election of the actual parliament, had already donated it for the Paulskirche. In fact, the picture can already be seen on a lithograph of the Pre-Parliament (around 1 April).[6] The National Assembly, on the other hand, met for the first time only on 18 May.

Eduard von Steinle and his friends in the artist circle Deutsches Haus painted several Germania pictures in 1848. Perhaps the Paulskirche Germania is based on a design by Steinle that is thought to have been lost. The art historian Rainer Schoch considers a joint production possible in which Veit, Steinle and other artists of the Deutsches Haus were involved. This may have included Karl Ballenberger, by whom a Germania is also known.[7]

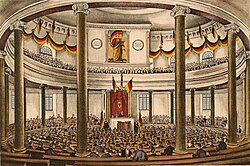

Context of presentation

editThe Paulskirche building was converted into a parliamentary hall during the revolutionary period. The speaker's lectern of the presidium replaced the pulpit. A wall behind the lectern was painted with a double-headed eagle, accompanied by black-red-gold flags.[8]

The image of Germania hung above the lectern, thus obscuring the church organ. It was five metres high and painted on a thin cotton fabric. In perspective, it was aimed at a viewer seated in the visitors' gallery. Two painted oak wreaths could be seen on the sides of the painting.

The members of parliament now saw the painting of Germania at every session. On 28 June 1848, they set up a German imperial government, the Provisional Central Authority. On 28 March 1849 they adopted an imperial constitution.

Later locations

editAfter the suppression of the revolution, the Paulskirche was used again for religious services. At first, no institution seemed to be responsible for the parliamentary inventory, such as the Imperial Library in the Paulskirche. In 1866, the German Confederation was dissolved. The Federal Liquidation Commission handed over the painting of Germania and other objects to the German National Museum (Germanisches Nationalmuseum) in Nuremberg in 1867. The museum displayed the painting once again in September 1870, on the occasion of the victories of the German troops in the Franco-Prussian War.[9]

Copies of the Germania from the Paulskirche are now in several museums. These include the House of History in Bonn and the Memorial to the Freedom Movements in German History in Rastatt.

-

The original, present-day exhibition in Nuremberg

-

Copy in the Memorial to the Freedom Movements

-

A maquette of the Paulskirche in the Memorial to the Freedom Movements

Symbolism

edit- Unfettered Shackle

- While shackles are a symbol of restriction or internment, unfettered shackles are a symbol of freedom, independence, or a new beginning. In national personification, this would indicate past control by another power or nation; either Rome historically, or more specifically, the Holy Roman Empire. (See Germany: History). However, this was most likely a symbol of the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte after his Conquest of Europe, of which largely sparked the nationalism that led to the German Revolution of 1848.

- Colors

- Note the prominent black, red and gold flag, which is still in use as the flag of Germany.

- Brandished Sword

- In this figure, the sword is brandished and held upright, in a gesture of leadership and defense, rather than offense or attack. Nobility, justice and truth are represented.

Broken chains: being free

Breastplate with eagle: strength

Crown of oak leaves: heroism

Olive Branch around the sword: willingness to make peace

Tricolour: flag of liberal-nationalists in 1848

Rays of sun from back: beginning of new era

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Rainer Schoch: "Streit um Germania. Bemerkungen zur 'Germania' aus der Paulskirche". In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (ed.): 1848: Das Europa der Bilder. Volume II: Michels März. Nuremberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1998, pp. 89–102, see p. 99.

- ^ Rainer Schoch: Streit um Germania. Bemerkungen zur ‚Germania‘ aus der Paulskirche. In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (ed.): 1848: Das Europa der Bilder. volume II: Michels März. Nürnberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1998, pp. 89–102, see p. 91/92.

- ^ Rainer Schoch: Streit um Germania. Bemerkungen zur ‚Germania‘ aus der Paulskirche. In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (ed.): 1848: Das Europa der Bilder. Volume II: Michels März. Nuremberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1998, p. 89.

- ^ Dieter Hein: Die Revolution von 1848/49, C. H. Beck, München 1998, p. 73.

- ^ Rainer Schoch: Streit um Germania. Bemerkungen zur ‚Germania‘ aus der Paulskirche. In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (ed.): 1848: Das Europa der Bilder. volume II: Michels März. Nürnberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1998, pp. 89–102, see p. 94.

- ^ Zitiert nach Rainer Schoch: Streit um Germania. Bemerkungen zur ‚Germania‘ aus der Paulskirche. In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (ed.): 1848: Das Europa der Bilder. volume II: Michels März. Nürnberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1998, pp. 89–102, see p. 91.

- ^ Rainer Schoch: Streit um Germania. Bemerkungen zur ‚Germania‘ aus der Paulskirche. In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (ed.): 1848: Das Europa der Bilder. volume II: Michels März. Nürnberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1998, pp. 89–102, see p. 99.

- ^ Rainer Schoch: Streit um Germania. Bemerkungen zur ‚Germania‘ aus der Paulskirche. In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (ed.): 1848: Das Europa der Bilder. volume II: Michels März. Nürnberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1998, S. 89.

- ^ Rainer Schoch: Streit um Germania. Bemerkungen zur ‚Germania‘ aus der Paulskirche. In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (ed.): 1848: Das Europa der Bilder. volume II: Michels März. Nürnberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1998, pp. 89–102, see p. 100.