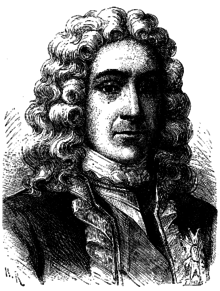

Jean-Florent de Vallière (7 September 1667 – 7 January 1759) was a French artillery officer of the 18th century. He was lieutenant-general of the King's Armies. In 1726, de Vallière became Director-General of the Battalions and Schools of the Artillery.

Vallière was a member of the Académie de Marine. After his death, his seat went to Chabert-Cogolin.[1]

Through the Royal Ordonnance of 7 October 1732, Vallière endeavoured to reorganize and standardize the King's artillery. He significantly improved the method used for founding cannons, superseding the technique developed by Jean-Jacques Keller. He thus developed the de Vallière system,[2] which set the standard for French artillery until the advent of the Gribeauval system.

Vallière system

editWhereas numerous formats and designs had been in place in the French army, Vallière standardized the French sizes in artillery pieces by allowing only for the production of 24 (Canon de 24), 12, 8 and 4 pound guns (the weight is the weight of the cannonballs), mortars of 12 and 8 French inches, and stone-throwing mortars of 15 French inches.[2]

The French pound weighing 1.097 English pounds, the French guns fired slightly heavier balls (13.164 pounds) than their English equivalent 12-pounder.[3] The French inch was 2.707 cm, slightly longer than the English inch of 2.54 cm.[4]

The Vallière system used core drilling of the bore of cannons founded in one piece of bronze, a method developed at that time by Jean Maritz, which allowed for much higher precision of the bore shape and surface, and therefore higher shooting efficiency.

The Valliere guns were also highly decorative and contained numerous designs and inscriptions.

-

French Classical Cannon, 17th-18th century.

-

Canon de 4 de Vallière, 1732, Le Pénétrant. Caliber: 84 mm.[5]

-

A Canon de 12 de Vallière, founded by Jean Maritz in 1736. Caliber: 121 mm. Length: 290 cm.

-

A 24-pdr gun of de Vallière system (Canon de 24 de Vallière, Uranie), founded by Jean Maritz in 1745.

Barrel

editThe back part occasionally included an inscription showing the weight of the cannonball (for example a "4" for a 4-pounder), followed by the Latin inscription "Nec pluribus impar," a motto of King Louis XIV and translated literally as "not unequal to many," but ascribed various meanings including "alone against all," "none his equal," or "capable of anything" among many others.[6][7][8][9] This was followed by the royal crest of the Bourbon dynasty. The location and date of manufacture were inscribed (in the example "Strasbourg, 1745") at the bottom of the gun, and finally the name and title of the founder (in the example "Fondu par Jean Maritz, Commissaire des Fontes").[10] The breech was decorated with an animal face showing the rating of the gun (in the example the lion head for a 24-pounder).

-

Back part of the de Valliere 24-pdr gun Uranie.

-

De Vallière 24-pdr guns, Les Invalides.

-

The de Vallière cannons were drilled after being founded in one piece, according to the method developed by Jean Maritz.

Breech design

editThe guns had cascabel designs which allowed to easily recognize their rating: a 4-pounder would have a "Face in a sunburst", an 8-pounder a "Monkey head", a 12-pounder a "Rooster head", a 16-pounder a "Medusa head", and a 24-pounder a "Bacchus head" or a "Lion head".[10]

Operational activity

editThe Valliere guns proved rather good in siege warfare but were less satisfactory in a war of movement.[2] That was especially visible during the War of the Austrian Succession (1747–1748) and during the Seven Years' War (1756–1763) in which mobility was a key factor and lighter guns were clearly in need. The lack of howitzers was another issue.[11]

Numerous Valliere guns were used in the American War of Independence, especially the smaller field guns. The guns were shipped from France and the field carriages provided for in the US. The guns played an important role in such battles as the Battle of Saratoga,[10] and the Siege of Yorktown. George Washington wrote about the guns in a letter to General William Heath on 2 May 1777:

"I was this morning favored with yours containing the pleasing accounts of the late arrivals at Portsmouth and Boston. That of the French ships of war, with artillery and other military stores, is most valuable. It is my intent to have all the arms that were not immediately wanted by the Eastern States, to be removed to Springfield, as a much safer place than Portsmouth …. I shall also write Congress and press the immediate removal of the artillery, and other military stores from Portsmouth. I would also have you forward the twenty-five chests of arms lately arrived from Martinico to Springfield."

Obsolescence

editHiss son, Joseph Florent de Vallière (1717–1776), who became Commander of the Battalions and Schools of the Artillery in 1747, persisted in implementing his father's system. From 1763, Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval, as Inspector General of the French Artillery, and second in rank to de Vallière, started efforts to introduce the more modern system that would give France one of the strongest artilleries for the following century.[12]

-

"The surrender at Saratoga" shows General Daniel Morgan in front of a de Vallière 4-pounder.

-

US Army personnel with a de Vallière 4-pounder in the 1960s. The carriage belongs to the 20-pounder Parrott rifle.

Notes

edit- ^ Doneaud Du Plan (1878), p. 64.

- ^ a b c A Dictionary of Military History and the Art of War By André Corvisier, p.837 [1]

- ^ History.navy.mil

- ^ Chartrand, p.2

- ^ a b c d e A Dictionary of Military History and the Art of War by André Corvisier, John Childs, John Charles Roger Childs, Chris Turner Page 42 [2]

- ^ Martin, Henri (1865). Martin's History of France: 1661-1683. Walker, Wise and Company.

- ^ Martin, John Rupert (1977). Baroque (1 ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-435332-X. OCLC 3710397.

- ^ Berger, Robert W. (1993). The palace of the sun : the Louvre of Louis XIV. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00847-4. OCLC 24912717.

- ^ Riley, Philip F. (2001). A lust for virtue : Louis XIV's attack on sin in seventeenth-century France. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-00106-5. OCLC 50321974.

- ^ a b c d Springfield Armory

- ^ Napoleon's Guns, 1792-1815 by René Chartrand, Ray Hutchins, p.2

- ^ Napoleon's Guns, 1792-1815 by René Chartrand, Ray Hutchins, p.6

References

edit- Chartrand, René 2003 Napoleon's guns 1792-1815 (2) ISBN 1-84176-460-4 Osprey Publishing

- Doneaud Du Plan, Alfred (1878). Histoire de l'Académie de marine (in French). Paris: Berger-Levrault.