The politics of Europe deals with the continually evolving politics within the continent of Europe.[1] It is a topic far more detailed than other continents due to a number of factors including the long history of nation states in the region as well as the modern day trend towards increased political unity amongst the European states.

The current politics of Europe can be traced back to historical events within the continent. Likewise geography, economy, and culture have contributed to the current political make-up of Europe.[1]

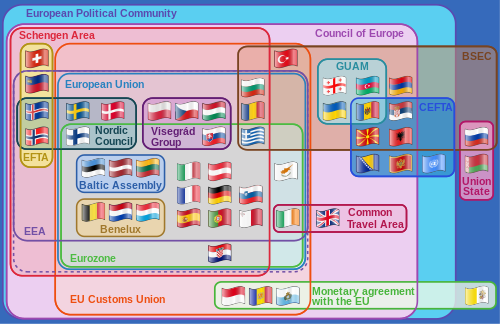

Modern European politics is dominated by the European Union, since the fall of the Iron Curtain and the collapse of the Eastern Bloc of Communist states.[2] After the end of the Cold War, the EU expanded eastward to include the former Communist countries. As of 31 January 2020, the EU has 27 member states.[3]

However, there are a number of other international organizations made up predominantly of European nations, or explicitly claiming a European origin, including the 46-nation Council of Europe - the first post-war European organization, regarded as a fore-runner to the European Union - and the 57-nation Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which also includes the United States and Canada, as well as some central Asian states.[4]

Modern political climate

editDespite vastly improved relations between Russia and the Western European states since the end of the cold war, recently tensions have risen over the spread of "Western" organizations, particularly the EU and NATO, eastwards into former USSR states.[4]

Many European states have either joined or stated their ambition to join the European Union.

There are few conflicts within Europe, although there remain problems in the Western Balkans, the Caucasus, Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom and the Basque Country in Spain.[5]

According to 2007 data published in 2008 by Freedom House, the countries of Europe that cannot be classified liberal electoral democracies are Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia, Kazakhstan and Russia.[6]

International unions, organizations and alliances

editEuropean states are members of a large number of international organizations, mainly economical, although several are political, or both. The main political unions are detailed below.

European Union

edit- Also see: Politics of the European Union, Enlargement of the European Union, Future enlargement of the European Union, Foreign relations of the European Union, Eastern Partnership

The European Union, or EU, is a political union of 27 states. It has many activities, the most important being a common single market, consisting of a customs union, a single currency (adopted by 20 of 27 member states),[7] a Common Agricultural Policy and a Common Fisheries Policy. The European Union also has various initiatives to co-ordinate activities of the member states.

The EU, considered as a unit, has the second largest economy in the world with a nominal GDP of 14.9 trillion USD in 2020.[8] There is also a trend of moving towards increased co-operation in terms of common defense and foreign policy.

The union has evolved over time from a primarily economic union to an increasingly political one. This trend is highlighted by the increasing number of policy areas that fall within EU competence; political power has tended to shift upwards from the member states to the EU. The further development of the political competencies of the EU is the subject of heavy debate within and between some member states.[9]

Council of Europe

editThe Council of Europe brings together 46 European nations - the entire continent with the exception of Russia, which was expelled in 2022 following its invasion of Ukraine, and Belarus.[10] Founded in 1949, it is the oldest of the European organizations, embodying post-war hopes for peaceful co-operation, and is focused on the three statutory aims of promoting human rights, democracy and the rule of law. It does not deal with economic matters or defense. Its main achievement is the European Convention on Human Rights, which binds its 46 contracting parties to uphold the basic human rights of their citizens, and the Strasbourg Court which enforces it.[11] The Council of Europe is regarded as a classic intergovernmental organization, with a parliamentary arm, and has none of the supranational powers of the EU – thus it could be compared to a regional version of the United Nations.

European Political Community

editThe European Political Community (EPC) was formed in October 2022 after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[12] The group first met in October 2022 in Prague, with participants from 44 European countries, as well as representatives of the European Union. Russia and Belarus were not invited to the inaugural meeting. It is envisioned that the group will meet twice in plenary session twice each year.

Community of Democratic Choice

editThe Community of Democratic Choice (CDC) was formed in December 2005 at the primary instigation of Ukraine and Georgia, and composed of six Post-Soviet states (Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, and the three Baltic Assembly members of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) and three other countries of Eastern and Central Europe (Slovenia, Romania and North Macedonia). The Black Sea Forum (BSF) is a closely related organization. Observer countries include Armenia, Bulgaria, and Poland.[13]

Just like GUAM before it, this forum is largely seen as intending to counteract Russian influence in the area. This is the only international forum centered in the post-Soviet space in which the Baltic states also participate. The other three post-Soviet states in it are all members of GUAM.[14]

Eurasian Economic Union

editThe Eurasian Economic Union is an economic union of post-Soviet states. The treaty aiming for the establishment of the EEU was signed on 29 May 2014 by the leaders of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia, and came into force on 1 January 2015.[15] Treaties aiming for Armenia's and Kyrgyzstan's accession to the Eurasian Economic Union were signed on 9 October 2014 and 23 December respectively. Armenia's accession treaty came into force on 2 January 2015.[16] Although Kyrgyzstan's accession treaty did not come into force until May 2015, provided it has been ratified,[17] it will participate in the EEU from the day of its establishment as an acceding state.[18][19][20][21][22] Moldova and Tajikistan are prospective members.

Euronest Parliamentary Assembly

editThe Euronest Parliamentary Assembly is the inter-parliamentary forum in which members of the European Parliament and the national parliaments of Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia participate and forge closer political and economic ties with the European Union.[23]

Commonwealth of Independent States

editThe Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is a confederation consisting of 12 of the 15 states of the former Soviet Union, (the exceptions being the three Baltic states).[24] Although the CIS has few supranational powers, it is more than a purely symbolic organization and possesses coordinating powers in the realm of trade, finance, lawmaking and security. The most significant issue for the CIS is the establishment of a full-fledged free trade zone and economic union between the member states, launched in 2005. It has also promoted co-operation on democratization and cross-border crime prevention. Additionally, six members of the CIS signed on to a collective security treaty known as the Collective Security Treaty Organization.[25]

Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations

editThe post-Soviet disputed states of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria are all members of the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations which aims to forge closer integration among the members.[26]

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

editThe North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is a military alliance of mainly European states, together with the United States of America and Canada. The organization was founded as a collective security measure following Second World War.[27]

This provision was intended so that if the Soviet Union launched an attack against the European allies of the United States, it would be treated as if it were an attack on the United States itself, which had the biggest military and could thus provide the most significant retaliation. However, the feared Soviet invasion of Europe never came. Instead, the provision was invoked for the first time in the treaty's history on 12 September 2001, in response to the attacks of 11 September on the United States the day before.

GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development

editGUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development is a regional organization of four CIS states: Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Moldova. The group was created as a way of countering the influence of Russia in the area, and it has received backing and encouragement from the United States .[28] Though at one point it was generally considered to have stagnated, recent developments have caused speculation on the possible revival of the organization.

Secessionist and devolutionary pressures

editThese movements, seeking either autonomy or independence, vary greatly in their popular support and political profile, from fringe movements to mainstream campaigns.

Belgium

editTwo of Belgium's political parties, the Vlaams Belang and New-Flemish Alliance, want Flanders, the northern part of the country, to become independent. Other Flemish parties plead for more regional autonomy. There is also a minor movement aiming at unification of Flanders with the Netherlands (see Greater Netherlands).[29]

The autonomous Belgian region of Wallonia has an almost extinct movement seeking unification with France.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

editSome inhabitants of Republika Srpska, one of the two constituent entities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (the other being the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina), the vast majority of them being ethnic Serbs, would opt for independence from Bosnia and Herzegovina and unification with Serbia. Republika Srpska comprises 49% of the territory of Bosnia and functions independently from the rest of the country in many spheres.[30] Even though independence is not on the official government agenda, Serbian politicians from the region see a link between a possible future status of Kosovo and the status of Republika Srpska.

Croats, who remain a constituent nation of Bosnia and Herzegovina remain united with ethnic Bosniaks in a joint entity. Some Bosnian Croat politicians have proposed a separate constituent entity for Croats along the lines of the Republika Srpska.[31]

Denmark

editThe Danish territories of Greenland and Faroe Islands have very strong independence movements. Greenland's autonomy marks it as a constituent country under the Danish kingdom.[32]

Finland

editThe Åland Islands has an autonomy. In 2003, the Ålandian separatist party Ålands Framtid was formed. There has not been much support for full independence since the Independence of Finland, but in the last years the support has slightly grown.[33]

France

editThe Mediterranean island of Corsica has a significant and growing group calling for independence from France. There are also movements in the Brittany region of northern France who wish to regain independence lost in 1532, and in Savoy in the south east, which was annexed to France following a disputed referendum in 1860.[34]

Parts of Navarre, Basque Country and Catalonia cross into France.

Georgia

editSouth Ossetia declared independence on 28 November 1991, and Abkhazia on 23 July 1992. Following the brief 2008 South Ossetia war, both entities were partially recognised as independent by several UN member states. Georgia considers both "occupied territories" within its own borders. Both states participate in the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations.[35]

Italy

editItaly has been a unitary parliamentary republic since 1946, when the monarchy was abolished. The president of Italy, Sergio Mattarella since 2015, is Italy's head of state. The president is elected for a single seven-year term by the Italian Parliament and regional voters in joint session. Italy has a written democratic constitution that resulted from a Constituent Assembly formed by representatives of the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the liberation of Italy, in World War II.[36]

Italy has a parliamentary government based on a mixed proportional and majoritarian voting system. The parliament is perfectly bicameral; each house has the same powers. The two houses: the Chamber of Deputies meets in Palazzo Montecitorio, and the Senate of the Republic in Palazzo Madama. A peculiarity of the Italian Parliament is the representation given to Italian citizens permanently living abroad: 8 Deputies and 4 Senators are elected in four distinct overseas constituencies. There are senators for life, appointed by the president "for outstanding patriotic merits in the social, scientific, artistic or literary field". Former presidents are ex officio life senators.

The prime minister of Italy is head of government and has executive authority, but must receive a vote of approval from the Council of Ministers to execute most policies. The prime minister and cabinet are appointed by the president, and confirmed by a vote of confidence in parliament. To remain as prime minister, one has to pass votes of confidence. The role of prime minister is similar to most other parliamentary systems, but they are not authorised to dissolve parliament. Another difference is that the political responsibility for intelligence is with the prime minister, who has exclusive power to coordinate intelligence policies, determine financial resources, strengthen cybersecurity, apply and protect State secrets, and authorise agents to carry out operations, in Italy or abroad.[37]

The major political parties are the Brothers of Italy, Democratic Party, and Five Star Movement. During the 2022 general election, these three and their coalitions won 357 of the 400 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, and 187 of 200 in the Senate. The centre-right coalition, which included Giorgia Meloni's Brothers of Italy, Matteo Salvini's League, Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia, and Maurizio Lupi's Us Moderates, won most seats in parliament. The rest were taken by the centre-left coalition, which included the Democratic Party, the Greens and Left Alliance, Aosta Valley, More Europe, Civic Commitment, the Five Star Movement, Action – Italia Viva, South Tyrolean People's Party, South calls North, and the Associative Movement of Italians Abroad.

Moldova

editThe eastern Moldovan region of Transnistria, which has a large ethnic Russian and Ukrainian population,[38] has declared independence from Moldova on 2 September 1990 and is a member of the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations.[39] Despite having no control over the region, the Moldovan government refuses to recognise this claim. There is a significant movement in Moldova and Romania aiming at the reunification of the two countries.

Netherlands

editThe Frisian National Party seeks more autonomy for Friesland without striving for complete independence. The preservation of Frisian culture is an important goal of the party.

Romania

editBefore the Treaty of Trianon after World War I, Transylvania belonged to Austria-Hungary, and it contains minorities of ethnic Hungarians who desire regional autonomy in the country.[40]

Russia

editSeveral of Russia's regions have independence movements, mostly in the state's north Caucasus border. The most notable of these are Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia, which have well supported guerrilla groups involved in open conflict with the Russian authorities.[41]

Some Tatar people seek independence for the region of Tatarstan[42]

Serbia

editThe status of Kosovo is the subject of a long-running political and territorial dispute between the Serbian (and previously, the Yugoslav) government and Kosovo's largely ethnic-Albanian population. International negotiations began in 2006 to determine final status (See Kosovo status process). Kosovo declared independence on 17 February 2008.[43]

Spain

editWithin Spain there are independence movements in some of the autonomous regions, notably the regions that have co-official languages such as Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Galicia. These are mostly peaceful but some, such as ETA and Terra Lliure, have used violent means.[44]

Ukraine

editThe Ukrainian autonomous region of Crimea has been annexed by the Russian Federation. The eastern, majority Russophone part of the country is divided, and there are calls from some groups for the area to leave Ukraine and join Russia.[45]

United Kingdom

editIn Northern Ireland, Sinn Féin and the Social Democratic and Labour Party achieve between them around 40% of the vote at elections,[46][47] with both parties supporting Northern Ireland leaving the United Kingdom and joining Ireland to create a United Ireland.[48][49]

In Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP), the Scottish Greens, the Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) and the Alba Party all support Scottish independence.[50] The SNP won an outright majority at the 2011 Scottish Parliament election and held the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, in the majority of Scottish voters backed remaining part of the United Kingdom by a 55% - 45% margin. There have, however, been revived calls for independence since the 2016 EU referendum, which saw both Scotland and Northern Ireland vote to Remain.[51]

In Wales, Plaid Cymru and the Propel support Welsh independence. Polls generally show support for Welsh independence at around 20-25%.[52]

In England, there are movements, such as the English Democrats, calling for a devolved English Parliament.[53][54] There are also movements, such as the Wessex Regionalists, calling for devolution of power to the English regions. Movements seeking autonomy[55][56] or independence[57] include Mebyon Kernow in the peninsula of Cornwall.[58][59]

As of 24 June 2016, the United Kingdom officially voted to leave the European Union. It is currently an ongoing process before the process of withdrawing officially begun on 29 March 2019. However, individual constituent countries within the United Kingdom, more specifically Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the European Union, prompting calls for another independence referendum in Scotland as well as raising the possibility of Irish reunification.[60]

See also

edit- Council of Europe

- International organizations in Europe

- Politics of the European Union

- European Neighborhood Policy

- European integration

- Eurovoc

- Eurosphere

- Culture of Europe

- Economy of Europe

- Future enlargement of the European Union

- Geography of Europe

- History of Europe

- List of conflicts in Europe

- List of Europe-related topics

- OSCE countries statistics

- Paneuropean Union

- Pro-Europeanism

- Regions of Europe

- Democracy in Europe

References

edit- ^ a b "The EU - what it is and what it does". op.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Milestones: 1989–1992 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "The Enlargement of the Union | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe". osce.org. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Kartsonaki, Argyro; Wolff, Stefan (3 April 2015). "The EU's Responses to Conflicts in its Wider Neighbourhood: Human or European Security?". Global Society. 29 (2): 199–226. doi:10.1080/13600826.2015.1021242. ISSN 1360-0826. S2CID 143843477.

- ^ freedomhouse.org: Map of Freedom in the World, 2008

- ^ "What is the euro area?".

- ^ "Economy". european-union.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "EUR-Lex - ai0020 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "The Russian Federation is excluded from the Council of Europe - Portal - publi.coe.int". Portal. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "European Convention on Human Rights - The European Convention on Human Rights - publi.coe.int". The European Convention on Human Rights. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Tidey, Alice (5 October 2022). "What we know and don't know about the new European Political Community". euronews. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ Peuch, Jean-Christophe (8 April 2008). "Ukraine: Regional Leaders Set Up Community Of Democratic Choice". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "GUAM: Still Relevant Regional Actor?". Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Договор о Евразийском экономическом союзе". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Дмитрий. "ДОГОВОР О ПРИСОЕДИНЕНИИ РЕСПУБЛИКИ АРМЕНИЯ К ДОГОВОРУ О ЕВРАЗИЙСКОМ ЭКОНОМИЧЕСКОМ СОЮЗЕ ОТ 29 МАЯ 2014 ГОДА (Минск, 10 октября 2014 года)". customs-code.ru. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ "Finalization of ratification procedures on Armenia's accession to EEU to be declared in Moscow today". Public Radio of Armenia. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ "Kyrgyzstan, Armenia officially enter Eurasian Economic Union". World Bulletin. 24 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

Signed agreement opens up new possibilities for Kyrgyzstan and Armenia, starting from 1st January 2015

- ^ "Putin said the accession of Kyrgyzstan to the EAEC" (in Russian). Life News. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

Kyrgyzstan is among the member countries of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEC). Kyrgyzstan will participate in the governing bodies of the EAEC since the start of the Union - from 1 January 2015.

- ^ "EAEC: stillborn union?" (in Russian). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

Eurasian Economic Union added December 23 Armenia and Kyrgyzstan.

- ^ Farchy, Jack (23 December 2014). "Eurasian unity under strain even as bloc expands". The Financial Times. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

Kyrgyzstan on Tuesday a signed a treaty to join the Eurasian Economic Union, expanding the membership of Moscow-led project to five even as its unity is strained by the market turmoil gripping Russia.

- ^ "Eurasian Economic Union to Launch on January 1". The Trumpet. 24 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan agreed to a January 1 inauguration.

- ^ "Initial Agreement Reached To Establish Parliamentary Assembly Of European Parliament's Eastern Neighbors". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- ^ "Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)". The Nuclear Threat Initiative. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Mag, Melange (1 October 2016). "Afro – Eurasian economic & trade blocs accelerate business activities". Melange Magazine. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "News Article". css.ethz.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Milestones: 1945–1952 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Organization for Democracy and Economic Development". GUAM. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Times, The Brussels. "Far-right Vlaams Belang party wants to declare Flemish sovereignty in 2029". www.brusselstimes.com. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Keil, Soeren (2017). "The Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Kosovo". European Review of International Studies. 4 (2+3): 39–58. doi:10.3224/eris.v4i2-3.03. ISSN 2196-6923. JSTOR 26593793.

- ^ Magnusson, Kjell (2012). "What kind of state?: Views of Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs on the character of Bosnia and Herzegovina". Socioloski Godisnjak (7): 37–62. doi:10.5937/socgod1207037m. ISSN 1840-1538. S2CID 142342062.

- ^ Kočí, Adam; Baar, Vladimír (8 August 2021). "Greenland and the Faroe Islands: Denmark's autonomous territories from postcolonial perspectives". Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography. 75 (4): 189–202. doi:10.1080/00291951.2021.1951837. ISSN 0029-1951. S2CID 237714542.

- ^ "The special status of the Åland Islands". Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Europe Government". www.university-world.com. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Time to Talk Trade". www.crisisgroup.org. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Smyth, Howard McGaw Italy: From Fascism to the Republic (1943–1946) The Western Political Quarterly vol. 1 no. 3 (pp. 205–222), September 1948.JSTOR 442274

- ^ "About us – Sistema di informazione per la sicurezza della Repubblica". sicurezzanazionale.gov.it. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Potter, Benjamin (2022). "Unrecognized Republic, Recognizable Consequences: Russian Troops in "Frozen" Transnistria". Journal of Advanced Military Studies. 13 (1): 168–188. doi:10.21140/mcuj.2022SIstratcul010. ISSN 2164-4217. S2CID 247608388.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Transnistria (unrecognised state)". Refworld. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Treaty of Trianon | World War I [1920] | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Chronology for Chechens in Russia". Refworld. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Chronology for Tatars in Russia". Refworld. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Kosovo conflict | Summary & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Shabad, Goldie; Gunther, Richard (1982). "Language, Nationalism, and Political Conflict in Spain". Comparative Politics. 14 (4): 443–477. doi:10.2307/421632. ISSN 0010-4159. JSTOR 421632.

- ^ "Ukraine - The crisis in Crimea and eastern Ukraine | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Northern Ireland election overview BBC News, 13 March 2007

- ^ "Northern Ireland Assembly election 2017 results - BBC News". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Maillot, Agnès. (2005). The new Sinn Féin : Irish republicanism in the twenty-first century. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32196-4. OCLC 54853257.

- ^ Whiting, Matthew (6 March 2017). "One step closer to a united Ireland? Explaining Sinn Féin's electoral success". British Politics and Policy at LSE. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ James, Steve. "Scottish National Party's fourth election win threatens UK breakup". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Forrest, Adam (4 May 2021). "Could an independent Scotland re-join the EU by 2031?". The Independent. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Langfitt, Frank (3 May 2021). "Behind The Surge In Support For Welsh Independence". NPR. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "English Parliament". Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "No English parliament - Falconer". 10 March 2006. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "About the Campaign for a Cornish Assembly". Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ "Policies - Mebyon Kernow". Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Morris, Steven (19 January 2002). "How three Cornish men and a raid on King Arthur's castle rocked English Heritage". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Cornwall's independence party Mebyon Kernow celebrates its 70th anniversary". InYourArea.co.uk. 5 January 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Leigh-Hewitson, Nadia (29 April 2021). "Why Cornish independence could be no joke". Prospect Magazine. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Wharton, Jane (31 January 2020). "What does Brexit mean for Scotland and Northern Ireland?". Metro. Retrieved 20 May 2021.