Carinthia (German: Kärnten [ˈkɛʁntn̩] ; Slovene: Koroška [kɔˈɾóːʃka] ; Italian: Carinzia [kaˈrintsja]) is the southernmost and least densely populated Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The main language is German. Its regional dialects belong to the Southern Bavarian group. Carinthian Slovene dialects, forms of a South Slavic language that predominated in the southeastern part of the region up to the first half of the 20th century, are now spoken by a small minority in the area.

Carinthia

Kärnten | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Kärntner Heimatlied | |

| |

| Country | |

| Capital | Klagenfurt |

| Government | |

| • Body | Landtag of Carinthia |

| • Governor | Peter Kaiser (SPÖ) |

| • Deputy Governors |

|

| Area | |

• Total | 9,364 km2 (3,615 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3,798 m (12,461 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 339 m (1,112 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2023) | |

• Total | 568,984 |

| • Density | 61/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| GDP | |

| • Total | €22.692 billion (2021) |

| • Per capita | €40,300 (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | AT-2 |

| HDI (2022) | 0.913[3] very high · 7th of 9 |

| NUTS Region | AT2 |

| Votes in Bundesrat | 4 (of 62) |

| Website | www.ktn.gv.at |

Carinthia's main industries are tourism, electronics, engineering, forestry, and agriculture.

Name

editThe etymology of the name "Carinthia", similar to Carnia or Carniola, has not been conclusively established. The Ravenna Cosmography (about AD 700) referred to a Slavic "Carantani" tribe as the eastern neighbours of the Bavarians. In his History of the Lombards, the 8th-century chronicler Paul the Deacon mentions "Slavs in Carnuntum, which is erroneously called Carantanum" (Carnuntum, quod corrupte vocitant Carantanum) for the year 663.[4]

"Carantani" may have been formed from a toponymic base carant- which ultimately derives from pre-Indo-European root *karra 'rock'.[5] (cf. Friulian: carantàn), or that it is of Celtic origin and derived from *karantos 'friend, ally'.

Likewise, the Slovene name *korǫtanъ may have been adopted from the Latin *carantanum. The toponym Carinthia (Slovene: Koroška < Proto-Slavic *korǫt’ьsko) is also claimed to be etymologically related, deriving from pre-Slavic *carantia.[6]

Carinthia is known as Koruška/ Корушка in Croatian and Serbian, Korutany in Czech, Kärnten in German, Karintia in Hungarian, Carinzia in Italian, Carintia in Spanish, Karyntia in Polish, Korutánsko in Slovak, and Koroška in Slovene.

Geography

editThe state stretches about 180 km (110 mi) from east to west, and 70 km (43 mi) in a north–south direction. With 9,536 km2 (3,682 sq mi), it is the fifth-largest Austrian state by area. Most of the larger Carinthian towns and lakes are situated within the Klagenfurt Basin in the southeast, an inner Alpine sedimentary basin covering about one-fifth of the area. These Lower Carinthian lands differ from the mountainous Upper Carinthian region in the northwest, stretching up to the Alpine crest.

The Carinthian lands are confined by mountain ranges: the Carnic Alps and the Karawanks form the border to Italy (Friuli-Venezia Giulia) and Slovenia (Carinthia Statistical Region, Savinja Statistical Region and Upper Carniola Statistical Region). The High Tauern mountain range with Mt Grossglockner, 3,797 m (12,457 ft), separates it from the state of Salzburg in the northwest. To the northeast and east beyond the Pack Saddle mountain pass is the state of Styria. The main river of Carinthia is the Drava (Drau), it makes up a continuous valley with East Tyrol, Tyrol to the west. Tributaries are the Gurk, the Glan, the Lavant, and the Gail rivers. Carinthia's lakes including Wörther See, Millstätter See, Lake Ossiach, and Lake Faak are a major tourist attraction.

The capital city is Klagenfurt. The next important town is Villach, both strongly linked economically. Other major towns include Althofen, Bad Sankt Leonhard im Lavanttal, Bleiburg, Feldkirchen, Ferlach, Friesach, Gmünd, Hermagor, Radenthein, Sankt Andrä, Sankt Veit an der Glan, Spittal an der Drau, Straßburg, Völkermarkt, Wolfsberg.

Carinthia has a humid continental climate (Köppen), with hot and moderately wet summers and long harsh winters. In recent decades, winters have been exceptionally arid. The summer precipitation maxima often takes the form of heavy rain and thunderstorms, especially in the mountainous regions. The main Alpine ridge in the north is a meteorological divide with pronounced windward and leeward sides where foehn occurs regularly.

Due to the diversified terrain, numerous distinct microclimates exist. Nevertheless, the average amount of sunshine hours is the highest of all states in Austria. In autumn and winter, temperature inversion often dominates the climate, characterized by air stillness, a dense fog covering the frosty valleys and trapping pollution to form smog, while mild sunny weather is recorded higher up in the foothills and mountains.

History

editThe settlement history of Carinthia dates back to the Paleolithic era. Archaeological findings of stone artifacts in a stalactite cave near Griffen are older than 30,000 years; larger settlements in the Lavanttal, Maria Saal and Villach regions are documented from about 3000 BC. Remains of a prehistoric stilt house settlement were discovered at Lake Keutschach, today part of the Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps World Heritage Site. Skeleton finds from about 2000 BC (near Friesach) denote a permanent population, and intensive arable farming, as well as trading with salt and Mediterranean products, was common already during the periods of the Urnfield and Hallstatt culture. Hallstatt grave fields were discovered near Dellach (Gurina), Rosegg (Frög), and on the Gracarca mountain southeast of Lake Klopein.

Noricum

editAbout 300 BC, several Illyrian and Celtic tribes joined in the Kingdom of Noricum, centered on the capital Noreia, possibly located in the Zollfeld basin near the later Roman city of Virunum. Known for the production of salt and iron, the Kingdom maintained intensive trade relations with Etruscan peoples and over the centuries extended the borders of its realm up to the Danube in the north. The Roman Empire incorporated Noricum in 15 BC. Besides the administrative seat of Virunum, the cities of Teurnia, Santicum (Villach) and Iuenna (Globasnitz) arose as centres of Roman culture. The Noricum province remained strategically important as a mining area for iron, gold, and lead and as an agricultural region. In the reign of the Emperor Diocletian (245–313) Noricum split into two provinces: Noricum ripense ("Noricum along the river", the northern part southward from the Danube), and Noricum mediterraneum ("landlocked Noricum", the district south of the Alpine crest). Teurnia became the administrative seat of the latter, as well as an Early Christian episcopal see.

As the Roman Empire declined in the 5th century AD, the Noricum region was exposed to recurring campaigns of Germanic tribes, whereupon the population retired to hilltop settlements. In 408 Visigoth troops under King Alaric I entered Noricum from Italy across the Carnic Alps and allied with the Roman commander Stilicho, who as a result was deposed and executed for high treason (August 408). From 472 Ostrogoth and Alemannic forces campaigned in Noricum, which became a province of Odoacer's Kingdom of Italy in 476 and of the Ostrogothic Kingdom from 493. On the death of King Theoderic the Great in 526, the Italian kingdom finally collapsed and the East Roman Byzantine empire under Justinian I temporarily conquered the Noricum region in the course of the Gothic War of 535 to 554.

Carantania

editFrom 591 onwards, the Frankish king Theudebert I tried to break into the former Noricum region, and Bavarian settlers entered the area from the Puster Valley in the west. They were however repulsed by Slavic tribes, who, beset by Avar horsemen moved into present-day Carinthia from the east. About 600 the Slavic principality of Carantania arose, stretching along the valleys of the Drava, Mur and Sava rivers. The remaining Celto-Roman population was largely assimilated, jointly challenging Avar and Frankish advance. The name Carontani was first mentioned about 700; the lands of Carantanum were documented by the chronicler Paul the Deacon (d. 799). The principality was again centered on the historic Zollfeld valley, where the Prince's Stone bears witness to the ritual of the investiture of the Carantanian rulers exclusively in Slovene.

While the Carantanian rulers initially joined the tribal union of Samo's Empire, Prince Boruth turned to Duke Odilo of Bavaria in around 743 to ask for support against the Avar invaders. Aid was granted, however at the price of Bavarian overlordship. The Carantanian principality became part of the Bavarian stem duchy, while the area was Christianised for the second time by missionaries from the Salzburg diocese. Bishop Vergilius had Prince Boruth's son Cacatius and his nephew Cheitmar brought up in the Christian faith. In 767, at their request, the bishop sent Modestus to Carantania as a vicar and had churches built at Teurnia and Maria Saal. Upon a pagan uprising in 772, the forces of Odilo's son Duke Tassilo III of Bavaria again subdued the Carantanian lands.

In 788, Duke Tassilo III was finally deposed by the Frankish king Charlemagne, and his territories were incorporated into the Carolingian Empire. By the 843 Treaty of Verdun, the former Carantanian lands fell to the kingdom of East Francia ruled by Charlemagne's grandson Louis the German. The ritual of installation of the Carantanian dukes at the Prince's Stone near Karnburg in Slovenian was preserved until 1414, when Ernest the Iron was enthroned as Duke of Carinthia.

Duchy of Carinthia

editThe March of Carinthia arose in 889 from the territory bequeathed by Louis's son Carloman, king of Bavaria from 865 to 880, to his natural son Arnulf of Carinthia. Arnulf had already assumed the title of a Carinthian duke in 880 and followed his uncle Charles the Fat as King of East Francia in 887. The Duchy of Carinthia was finally split from the vast Bavarian duchy in 976 by Emperor Otto II, having come out victorious from his quarrels with Duke Henry II the Wrangler. Carinthia, therefore, was the first newly created duchy of the Holy Roman Empire and for a short while comprised lands stretching from the Adriatic Sea almost to the Danube. In 1040, the March of Carniola was separated from it, and c. 1180 Styria, the Carinthian March, became a duchy in its own right. After the death of Duke Henry VI of Gorizia-Tyrol in 1335, Carinthia passed to the Habsburg brothers Albrecht II. and Otto IV, and was ruled by this dynasty until 1918. After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, Carinthia was incorporated in the Austrian Empire's Kingdom of Illyria which succeeded Napoleon's Illyrian Provinces, but recovered its previous status in 1849 and in 1867 became one of the Cisleithanian crown lands of Austria-Hungary.

Formation of the state

editIn late 1918, the breakup of the Habsburg monarchy was imminent, and on 21 October 1918 the members of the Reichsrat for the German-speaking territories of Austria met in Vienna to constitute a "Provisional National Council for German-Austria". Before the meeting, the delegates agreed that German-Austria should not include "Yugoslav areas of settlement", which referred to Lower Styria and the two Slovene-speaking Carinthian valleys south of the Karawanken range, Seeland (Slovenian: Jezersko) and Mießtal (Meža Valley). On 12 Nov. 1918, when the Act concerning the foundation of the State of German-Austria was formally passed by the Provisional National Assembly in Vienna this was worded by the State Chancellor, Karl Renner, "...to encounter the prejudices of the world as though we wanted to annex alien national property"[7] The day before, on 11 Nov. 1918 the Provisional Diet of Carinthia had formally declared Carinthia's accession to the State of German-Austria.[8] The Federal Act concerning the Extent, the Borders and the Relations of the State Territories of 22 Nov. 1918 then clearly stated in article 1: "...the duchies of Styria and Carinthia with the exclusion of the homogenous Yugoslav areas of settlement".[9] Apart from one Social-Democrat, Florian Gröger, all the other delegates from Carinthia—Hans Hofer, Jakob Lutschounig, Josef Nagele, Alois Pirker, Leopold Pongratz, Otto Steinwender, Viktor Waldner—were members of German national parties and organizations.[10]

Disputed frontiers

editAfter the end of the World War I, however, Carinthia became a contested region. On 5 November 1918, the first armed militia units led by the Slovene volunteer Franjo Malgaj invaded Carinthia and were then joined by Slovene troops under Rudolf Maister. With the subsequent assistance of the regular Yugoslav army, they occupied southern Carinthia claiming the area for the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, or SHS) also known as Yugoslavia. The provisional state government of Carinthia had fled to Spittal an der Drau and given the ongoing fighting between local volunteers and invaders on 5 December decided to declare armed resistance. The resistance encountered by the Yugoslav forces especially north of the Drava River around the town of Völkermarkt with its violent fighting alarmed the victorious Allies at the Paris Peace Conference.

An Allied Commission headed by U.S. Lt.Col. Sherman Miles inspected the situation in situ and recommended the Karawanken main ridge as a natural border to keep the Klagenfurt basin intact but, in agreement with item no. 10 of Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, suggested a referendum in the disputed area. An armistice was agreed upon on 14 January and by 7 May 1919 the Yugoslav forces had left the state, but Slovene troops under Rudolf Maister returned to occupying Klagenfurt on 6 June. Upon the intervention of the Allied Supreme Council in Paris, they retreated from the city but remained in the disputed part of Carinthia until 13 September 1920.

In the Treaty of Saint-Germain of 10 September 1919, the two smaller Slovene-speaking Carinthian valleys south of the Karawanken range, Jezersko and the Meža Valley, together with the town of Dravograd—together 128 square miles[11] or 331 km2 (127.80 sq mi)—were attached to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia): These areas are today part of Slovene Carinthia. The Canale Valley (German: Kanaltal, Italian: Val Canale) as far south as Pontebba, at that time an ethnically mixed German–Slovene area,[citation needed] with the border town of Tarvisio (German: Tarvis, Slovene: Trbiž) and its holy place of pilgrimage of Maria Luschari (Slovene: Svete Višarje) (172 square miles[11] or 445 km2), was ceded to Italy and included in the Province of Udine.

According to the same treaty, a referendum was to be held in southern Carinthia as suggested by the Allied Commission, which was to determine whether the area claimed by the SHS-State was to remain part of Austria or go to Yugoslavia. Much of southern Carinthia was divided into two zones. Zone A was formed out of predominantly Slovene-inhabited zones (approximately corresponding to today's District of Völkermarkt, the district of Klagenfurt-Land south of lake Wörthersee, and the south-eastern part of the present district of Villach-Land), while Zone B included the City of Klagenfurt, Velden am Wörthersee and the immediately surrounding rural areas where German speakers formed a vast majority. If the population in Zone A had decided for Yugoslavia, another referendum in Zone B would have followed. On 10 October 1920, the Carinthian Plebiscite was held in Zone A, with almost 60% of the population voting to remain in Austria, which means that about 40% of the Slovene-speaking population must have voted against a division of Carinthia. Given the close supervision of the referendum by foreign observers, as well as the Yugoslav occupation of the area until four weeks before the referendum, irregularities alleged by the deeply disappointed Yugoslav supporters would not have substantially altered the overall decision. Yet, after the plebiscite, the SHS-State again made attempts to occupy the area, but owing to demarches by the United Kingdom, France, and Italy it removed its troops from Austria so that, by 22 November 1920, the State Diet of Carinthia was at last able to exercise its sovereignty over the entire state.[12]

After World War I to present

editOriginally an agrarian country, Carinthia made efforts to establish a touristic infrastructure such as the Grossglockner High Alpine Road and Klagenfurt Airport as well as the opening up of the Alps through the Austrian Alpine Club in the 1920s. It was, however, hard hit by the Great Depression around 1930, which pushed the political system in Austria more and more towards extremism. This phenomenon culminated at first in the years of Austrofascism and then in 1938 in the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany (Anschluss). At the same time the Nazi Party took power everywhere in Carinthia, which became, together with East Tyrol, a Reichsgau, and Nazi leaders such as Franz Kutschera, Hubert Klausner, and Friedrich Rainer held the office of Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter.

During World War II, Slovene Partisan resistance was active in the southern areas of the region, reaching around 3,000 armed men. The cities of Klagenfurt and Villach suffered from air raids, but the Allied forces did not reach Carinthia before May 8, 1945. Toward the end of the war, Gauleiter Rainer tried to implement a Nazi plan for Carinthia to become part of the projected Nazi national redoubt, the Alpenfestung; these efforts failed and the forces under Rainer's control surrendered to the forces of the British Army. Once again at the end of World War II, Yugoslav troops occupied parts of Carinthia, including the capital city of Klagenfurt, but were soon forced to withdraw by the British forces with the consent of the Soviet Union.

Carinthia, East Tyrol, and Styria then formed the UK occupation zone of Allied-administered Austria. The area was witness to the turnover of German-allied Cossacks to the Red Army in 1945. The Allied occupation was terminated in 1955 by the Austrian State Treaty, which restored Austria's sovereignty. The relations between the German- and the Slovene-speaking Carinthians remained somewhat problematic. Divergent views over the implementation of minority protection rights guaranteed by Article 7 of the Austrian State Treaty have created numerous tensions between the two groups in the past fifty years.[when?]

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1869 | 315,397 | — |

| 1880 | 324,857 | +3.0% |

| 1890 | 337,013 | +3.7% |

| 1900 | 343,531 | +1.9% |

| 1910 | 371,372 | +8.1% |

| 1923 | 371,227 | −0.0% |

| 1934 | 405,129 | +9.1% |

| 1939 | 416,268 | +2.7% |

| 1951 | 474,764 | +14.1% |

| 1961 | 495,226 | +4.3% |

| 1971 | 526,759 | +6.4% |

| 1981 | 536,179 | +1.8% |

| 1991 | 547,798 | +2.2% |

| 2001 | 559,404 | +2.1% |

| 2011 | 556,173 | −0.6% |

| 2021 | 564,328 | +1.5% |

| Source: Censuses[13] | ||

The largest part of Carinthia's population settles in the Klagenfurt Basin between Villach and Klagenfurt. In 2008, the proportion of the population with a migration background in Carinthia was 9.3% of the total population, about half the Austrian figure of 17.5%.[14] By 2020, the proportion of the population with a migration background in Carinthia had risen to 14.5%, yet this figure remains lower than the Austrian average, where close to a quarter of the population has a migration background.[15]

The majority of Carinthia's population is today German-speaking. In the south of the province (mainly in the districts of Villach-Land Klagenfurt-Land and Völkermarkt) live Carinthian Slovenes where they speak Slovene and are recognized as an autochthonous ethnic minority. The discussion about ethnic group rights (e.g. bilingual place-name signs) can be very emotional and the rights of Slovenes in Carinthia are still not fully implemented.

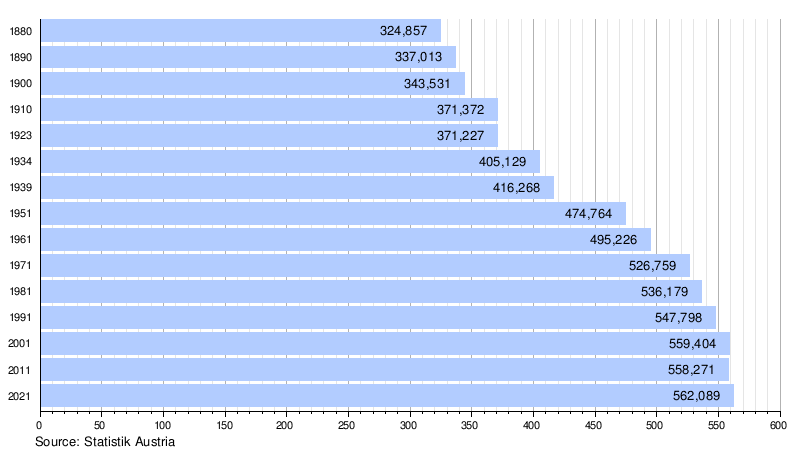

Population development

editThe historical population is given in the following chart:

Administrative divisions

editThe state is divided into eight rural and two urban districts (Bezirke), the latter being the statutory cities (Statutarstädte) of Klagenfurt and Villach. There are 132 municipalities, of which 17 are incorporated as towns and 40 are of the lesser market towns (Marktgemeinden) status.

Statutory cities

edit- Klagenfurt (licence plate code: K)

- Villach (VI)

Rural districts

edit- Feldkirchen (FE)

- Administrative seat: Feldkirchen

- Municipalities: Albeck • Glanegg • Gnesau • Himmelberg • Ossiach • Reichenau • Sankt Urban • Steindorf am Ossiacher See • Steuerberg

- Hermagor (HE)

- Administrative seat: Hermagor-Pressegger See

- Market towns: Kirchbach • Kötschach-Mauthen

- Municipalities: Dellach • Gitschtal • Lesachtal • Sankt Stefan im Gailtal

- Klagenfurt-Land (KL)

- Administrative seat: Klagenfurt (not part of the district)

- Town: Ferlach

- Market towns: Ebenthal • Feistritz im Rosental • Grafenstein • Magdalensberg • Maria Saal • Moosburg • Poggersdorf • Schiefling am See

- Municipalities: Keutschach am See • Köttmannsdorf • Krumpendorf • Ludmannsdorf • Maria Rain • Maria Wörth • Pörtschach • Sankt Margareten im Rosental • Techelsberg • Zell

- Sankt Veit an der Glan (SV)

- Administrative seat: Sankt Veit an der Glan

- Towns: Althofen • Friesach • Straßburg

- Market towns: Brückl • Eberstein • Gurk • Guttaring • Hüttenberg • Klein Sankt Paul • Liebenfels • Metnitz • Weitensfeld im Gurktal

- Municipalities: Deutsch-Griffen • Frauenstein • Glödnitz • Kappel am Krappfeld • Micheldorf • Mölbling • Sankt Georgen am Längsee

- Spittal an der Drau (SP)

- Administrative seat: Spittal an der Drau

- Towns: Gmünd • Radenthein

- Market towns: Greifenburg • Lurnfeld • Millstatt • Oberdrauburg • Obervellach • Rennweg am Katschberg • Sachsenburg • Seeboden • Steinfeld • Winklern

- Municipalities: Bad Kleinkirchheim • Baldramsdorf • Berg im Drautal • Dellach im Drautal • Flattach • Großkirchheim • Heiligenblut am Großglockner • Irschen • Kleblach-Lind • Krems • Lendorf • Mallnitz • Malta • Mörtschach • Mühldorf • Rangersdorf • Reißeck • Stall • Trebesing • Weissensee

- Villach-Land (VL)

- Administrative seat: Villach (not part of the district)

- Market towns: Arnoldstein • Bad Bleiberg • Finkenstein am Faaker See • Nötsch im Gailtal • Paternion • Rosegg • Sankt Jakob im Rosental • Treffen • Velden am Wörther See • Weißenstein

- Municipalities: Afritz am See • Arriach • Feistritz an der Gail • Feld am See • Ferndorf • Fresach • Hohenthurn • Stockenboi • Wernberg

- Völkermarkt (VK)

- Administrative seat: Völkermarkt

- Town: Bleiburg

- Market towns: Eberndorf • Eisenkappel-Vellach • Feistritz ob Bleiburg • Griffen

- Municipalities: Diex • Gallizien • Globasnitz • Neuhaus • Ruden • Sankt Kanzian am Klopeiner See • Sittersdorf

- Wolfsberg (WO)

- Administrative seat: Wolfsberg

- Towns: Bad Sankt Leonhard im Lavanttal • Sankt Andrä

- Market towns: Frantschach-Sankt Gertraud • Lavamünd • Reichenfels • Sankt Paul im Lavanttal

- Municipalities: Preitenegg • Sankt Georgen im Lavanttal

Politics

editThe state assembly Kärntner Landtag, ("Carinthian State Diet"), is a unicameral legislature. Its 36 members are elected from party lists according to the principle of proportional representation and serve five-year terms, with elections held every five years. Austrian nationals over the age of 16 residing in Carinthia are eligible to vote. The Landtag has a threshold of 5%.

The most recent election, the 2023 Carinthian state election, was held on 5 March 2023. The SPÖ, the party of the incumbent governor Peter Kaiser, won a plurality of the vote at 38.9%, giving them a plurality of seats. This makes Carinthia one of only 3 regions of Austria not to have an ÖVP-led government (alongside Vienna and Burgenland), although the ÖVP is the junior coalition member in Kaiser's government.

The legislature also elects the state government, composed of a minister-president or Governor, whose ancient title is Landeshauptmann ("State Captain"), his two deputies, and further four Landesräte ministers. The members of the cabinet used to form an all-party government elected under a system of proportional representation based on the number of representatives of the political parties in the Landtag in a system known as Proporz, however this system was abolished in Carinthia in 2017.[16]

Economy

editThe Gross domestic product (GDP) of the state was 20.9 billion € in 2018, accounting for 5.4% of Austria's economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was €33,000 or 110% of the EU27 average in the same year.[17]

Language

editGerman is the official language.[18]

The people are predominantly German-speaking with a unique (and easily recognizable) Southern Austro-Bavarian dialect typical of which is that all short German vowels before double consonants have been lengthened ("Carinthian vowel stretching").[citation needed]

A Slovene-speaking minority, known as the Carinthian Slovenes, is concentrated in the southern and southeastern parts of the state. Its size cannot be determined precisely because the representatives of the ethnic group reject a count.[citation needed] Recommendations for a boycott of the 2001 census, which asked for the language used in everyday communication, reduced the count of Slovene speakers to 12,554 people, 2.38% of a total population of 527,333.[19]

Tourist attractions

editMajor sights include the cities of Klagenfurt and Villach and medieval towns like Friesach or Gmünd. Carinthia features numerous monasteries and churches such as the Romanesque Gurk Cathedral or Maria Saal in the Zollfeld plain, the abbeys of St. Paul's, Ossiach, Millstatt, and Viktring as well as castles and palaces like large-scale Hochosterwitz, Griffen, or Porcia.

Scenic highlights are the main bathing lakes Wörthersee, Millstätter See, Ossiacher See and Faaker See as well as a variety of smaller lakes and ponds. In winter Carinthia offers ski resorts such as the Nassfeld near Hermagor, Gerlitzen mountain, Bad Kleinkirchheim, Flattach, and Heiligenblut at Austria's highest mountain, the Grossglockner as well as the Hohe Tauern and Nock Mountains national parks for all kind of alpine sports and mountaineering.

Culture

editCustoms and traditions

editOne of many customs that still subsists all over Carinthia are Kirchtage, a traditional type of fair. The most famous is Villacher Kirchtag in Villach, which was first held in 1936 and is very popular among locals and tourists.

Museums

editThe museums in Carinthia include the Carinthian State Museum with its locations in Klagenfurt, the Maria Saal open-air museum, the Magdalensberg Archaeological Park, and the Teurnia Roman Museum. One of the most important city museums is the City Museum of Villach, which documents, among other things, the life story of its temporary citizen Paracelsus.

Literature

editCarinthia has produced several internationally renowned writers in recent decades. In the early 20th century, Robert Musil, Josef Friedrich Perkonig, Dolores Viesèr, and Gerhart Ellert gained some notoriety.

After the Second World War, the poets Ingeborg Bachmann, Michael Guttenbrunner, and Christine Lavant first came to the fore. They were followed by Peter Handke, Gert Jonke, Josef Winkler, and Peter Turrini. Among other things, they took a very critical look at their homeland, like Josef Winkler in his trilogy "Das wilde Kärnten". Other important representatives of Carinthian literature include Janko Messner, Janko Ferk, Lydia Mischkulnig, Werner Kofler, Antonio Fian, and Florjan Lipus.

The most important publishers are Johannes Heyn, Carinthia, and the Carinthian printing and publishing company. Slovenian literature is primarily promoted by the Carinthian publishers Mohorjeva/Hermagoras, Drava, and the Wieser-Verlag founded by Lojze Wieser.

The most important literary event in Carinthia is the Days of German-language Literature in Klagenfurt, during which the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize is awarded, which has been held annually since 1977 and particularly supports younger authors. The Ingeborg Bachmann Prize is one of the most important literary awards in the German-speaking world.

Fine Arts

editIn the early 20th century, the Nötsch circle was active with the painters Sebastian Isepp, Franz Wiegele, Anton Kolig, and Anton Mahringer with its European orientation. The painter Herbert Boeckl was only loosely associated with the circle. An art-political controversy was the dispute over the Kolig frescoes in the Klagenfurt country house from 1931, which ended in the removal of the frescoes in 1938. In terms of architecture, Gustav Gugitz, the builder of the State Museum, should be mentioned, while the Wörthersee architecture with the villas and hotels is primarily characterized by Viennese architects. Switbert Lobisser is known for his woodcuts. Werner Berg made woodcuts and paintings, especially of his adoptive home in Bleiburg.

After 1945, Maria Lassnig, Hans Staudacher, and Hans Bischoffshausen initiated a radical new beginning. Important sites were and are the Carinthian Art Association, the Hildebrand Gallery, the Nötscher-Kreis-Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art Carinthia, which opened in 2003. Two high-profile "art scandals" were the frescoes by Giselbert Hoke in Klagenfurt main station in 1950 and the redesign of the meeting room in the country house in 1998 by Anton Kolig's grandson, Cornelius Kolig.

A fountain designed by Kiki Kogelnik stands near the country house. Other visual artists are Valentin Oman, Bruno Gironcoli, Meina Schellander, and Karl Brandstätter. In Carinthia, the architect Günther Domenig designed the Steinhaus am Ossiacher See, the building for the state exhibition in Hüttenberg and the extension for the Klagenfurt city theater.

Notable people

editBorn in Carinthia

edit- Arnulf of Carinthia, Holy Roman Emperor, born about 850, grew up in Moosburg, died December 8, 899 in Regensburg.

- Pope Gregory V (né Bruno of Carinthia), born about 972, place unknown, died February 18, 999, in Rome.

- Saint Hemma of Gurk, born about 980, probably at Zeltschach, Friesach, died June 27, 1045, in Gurk.

- Heinrich von dem Tuerlin, minstrel and epic poet, early 13th century, probably born at Sankt Veit an der Glan.

- Ulrich von dem Türlin, a 13th-century epic poet, probably born at St. Veit an der Glan.

- Henry of Carinthia, king of Bohemia (Jindřich Korutanský) and titular king of Poland, born about 1265, died April 2, 1335, at Castle Tyrol.

- Josef Stefan, physicist, born March 24, 1835, in the vicinity of Klagenfurt, died January 7, 1893, in Vienna.

- Thomas Koschat, composer and bass singer, born August 8, 1845, in Klagenfurt.

- Robert Musil, author, born November 6, 1880, in Klagenfurt, died April 15, 1942, in Geneva.

- Anton Wiegele, painter, born February 23, 1887, at Nötsch im Gailtal, died December 17, 1944, at Nötsch im Gailtal.

- Herbert Boeckl, painter, born June 3, 1894, in Klagenfurt, died January 20, 1966, in Vienna.

- Rudolf Kattnigg, composer, born April 9, 1895, in Treffen, died September 2, 1955, in Vienna.

- Josef Klaus, politician, born August 15, 1910, at Kötschach-Mauthen, died July 25, 2001, in Vienna.

- Heinrich Harrer, mountaineer and ethnographer, born July 6, 1912, at Obergossen, Hüttenberg, died January 7, 2006, at Friesach.

- Christine Lavant, poet, born July 4, 1915, in Großedling, Wolfsberg, died June 7, 1973, at Wolfsberg.

- Maria Lassnig, painter, born September 9, 1919, in Kappel am Krappfeld.

- Kathrin Glock, entrepreneur, born November 26, 1980, in Carinthia.

- Paul Watzlawick, psychologist, born July 25, 1921, in Villach, died March 31, 2007, in Palo Alto.

- Felix Ermacora, specialist in international law, born October 13, 1923, in Klagenfurt, died February 24, 1995, in Vienna.

- Ingeborg Bachmann, poet and writer, born June 25, 1926, in Klagenfurt, died October 17, 1973, in Rome.

- Gerhard Lampersberg, composer, born July 5, 1928, at Hermagor, died May 29, 2002, in Klagenfurt.

- Günther Domenig, architect, born July 6, 1934, in Klagenfurt, died 15 June 2012.

- Udo Jürgens, singer and composer, born September 30, 1934, in Klagenfurt, died December 21, 2014, in Münsterlingen, Switzerland.

- Kiki Kogelnik, painter, born January 22, 1935, at Bleiburg, died February 1, 1997, in Vienna.

- Bruno Gironcoli, sculptor, born September 27, 1936, at Villach, died February 19, 2010, in Vienna.

- Engelbert Obernosterer, writer, born December 28, 1936, at Sankt Lorenzen, Lesachtal.

- Dagmar Koller, actress and singer, born August 26, 1939, in Klagenfurt.

- Peter Handke, playwright and writer, born December 6, 1942, at Griffen.

- Arnulf Komposch, mirror artist, born 1942 in Klagenfurt.

- Peter Turrini, playwright, born September 26, 1944, at St. Margarethen im Lavanttal, Wolfsberg.

- Gert Jonke, playwright, born February 8, 1946, in Klagenfurt, died January 4, 2009.

- Werner Kofler, writer, born July 23, 1947, in Villach.

- Wolfgang Petritsch, diplomat, born August 26, 1947, in Klagenfurt.

- Erik Schinegger, intersexed alpine skier, born June 19, 1948, at Agsdorf, Sankt Urban.

- Wolfgang Puck, celebrity chef, born July 8, 1949, in Sankt Veit an der Glan.

- Josef Winkler, writer, born March 3, 1953, in Kamering.

- Franz Klammer, alpine skier, born December 3, 1953, at Mooswald, Fresach.

- Markus Müller, pharmacologist and rector of the Medical University of Vienna, born August 23, 1967, in Klagenfurt.

- Patrick Friesacher, Formula one driver, born September 26, 1980, in Wolfsberg.

Died in Carinthia

edit- Modestus, missionary, born about 720 in Ireland, died about 772 probably in Maria Saal.

- Bolesław II the Bold, king of Poland, born about 1042; according to legend, died in Ossiach March 22, 1081 (?).

- Carl Auer von Welsbach, chemist and inventor, born September 1, 1858, in Vienna, died August 4, 1929, in Möbling.

- Anton Kolig, painter, born July 1, 1886, at Neutitschein (today Nový Jičín, Czech Republic), died May 17, 1950, in Nötsch im Gailtal.

- Werner Berg, painter, born April 4, 1911, in Elberfeld, now Wuppertal, Germany, died September 7, 1981, in Sankt Veit im Jauntal, Sankt Kanzian am Klopeiner See.

- Milivoj Ašner, born April 21, 1913, in Daruvar, Croatia, died 14 June 2011, accused Ustaše war criminal.

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ "Geographische Werte – Marktgemeinde Lavamünd".

- ^ "Basisdaten Bundesländer" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ Simoniti Vasko, Štih Peter (1996): Slovenska zgodovina do razsvetljenstva. Celovec, Mohorjeva družba in Korotan.

- ^ "Home > Carinthia at first sight > History". ktn.gv.at. Retrieved 2015-10-04.

- ^ France Bezlaj, Etimološki slovar slovenskega jezika (Slovenian Etymological Dictionary). Vol. 2: K–O / edited by Bogomil Gerlanc. – 1982. p. 68. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1976–2005.

- ^ [1] Minutes of the Third Session of the Provisional National Assembly of German-Austria on 12 Nov. 1918], in: Austrian National Library, Minutes of the Parliamentary Sessions, p. 66

- ^ Kurze Geschichte Kärntens, in: Deutschösterreich, du herrliches Land. 90 Jahre Konstituierung der Provisorischen Nationalversammlung. Broschüre zum Festakt der österreichischen LandtagspräsidentInnen am 20. Oktober 2008, p.24

- ^ Bill by the State Council, Appendix No. 3 PDF

- ^ "Niederösterreichischer Landtag". noe-landtag.gv.at.

- ^ a b ”Kärnten". Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago 2010.

- ^ Claudia Fräss-Ehrfeld, Geschichte Kärntens 1918-1920. Abwehrkampf-Volksabstimmung-Identitätssuche, Klagenfurt: Johannes Heyn 2000. ISBN 3-85366-954-9

- ^ "Historic Censuses - STATISTICS AUSTRIA". Statistics Austria.

- ^ Statistik Austria, Österreichischer Städtebund: Österreichs Städte in Zahlen 2009. Statistik Austria, Wien 2009

- ^ "Österreich - Migrationshintergrund Bundesland 2020". Statista (in German). Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ^ "Kärnten schafft den Proporz ab" [Carinthia abolishes Proporz]. Die Presse (in German). 2017-07-11. Retrieved 2024-11-09.

- ^ "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- ^ "Kärntner Landesverfassung -K-LVG" (PDF).

- ^ "Bevölkerung mit österreichischer Staatsbürgerschaft nach Umgangssprache seit 1971" (in German). Statistik Austria. Archived from the original on 2009-06-20. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

External links

edit- Official website (in German, Italian, English, and Slovene)

- Carinthia Tourism

- Consuming Carinthia