Since the 18th century, there have been several editions of the Book of Common Prayer produced and revised for use by Unitarians. Several versions descend from an unpublished manuscript of alterations to the Church of England's 1662 Book of Common Prayer originally produced by English philosopher and clergyman Samuel Clarke in 1724, with descendant liturgical books remaining in use today.

Clarke, a Semi-Arian and Subordinationist, viewed the doctrine of the Trinity as theologically unsound and saw the 1662 prayer book's inclusion of elements like the Athanasian Creed as perpetuating these errors. Clarke's manuscript alterations emphasized the excision of Trinitarian references in favor of prayers directed toward God the Father. Theophilus Lindsey would build upon Clarke's work after receiving a copy of the changes, publishing his own series of Unitarian prayer books from 1774 onward. Lindsey's Essex Street Chapel in London, the first Unitarian church in England, utilized these prayer books for worship. When an Essex Street Chapel congregant introduced James Freeman of King's Chapel in Boston to Lindsey's prayer book, Freeman further edited its liturgies and convinced his congregation to adopt his revision in 1785.

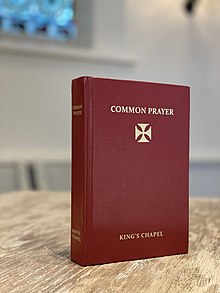

These Unitarian forms were among a trend of Nonconformist efforts to revise the 1662 prayer book through the 18th and 19th centuries; the Anglican prayer book remained the primary basis for English Unitarian worship literature until 1861. The Unitarian revisions influenced other prayer book revision efforts, including John Wesley's The Sunday Service of the Methodists and the American Episcopal Church's first attempted prayer book revision. The King's Chapel prayer book, currently in its ninth edition as first published in 1986, remains that congregation's standard liturgical text.

History

editLayman Edward Stephens published a book in 1696 that spurred a movement of suggested revisions to the Church of England's legally mandated liturgy, the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. The movement's proposals generally sought to "shorten and unify the service". Inspired by Stephens, William Whiston forwarded his own more unorthodox revisions in 1713, part of a trend that saw such proposals increasingly alter the Anglican prayer book in accordance with Arian and Unitarians theologies. However, these early revisions ultimately had little influence on later Nonconformist liturgies.[1][note 1] However, a set of Unitarian prayer book revisions by Samuel Clarke which were edited and published after his death by Theophilus Lindsey would heavily influence over a third of all English Dissenters liturgies for 80 years.[3]

Clarke, the Church of England rector of St James's Church, Piccadilly, privately created an altered version of the 1662 prayer book in 1724. He was a Semi-Arian and, like early Unitarians in Transylvania and what was then the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a subordinationist who held that God the Father was supreme and, unlike God the Son, alone worthy of worship.[4] Clarke had previously published a study of 1,250 Bible verses, The Scriptural Doctrine of the Trinity, in 1712.[note 2] This book contained Clarke's theology and prescribed a new rule for prayer based on the notion Jesus Christ derives his powers as savior from the Father.[8] In Clarke's view, the theology of the Trinity had developed as a result of poor metaphysics and the inclusion of the Athanasian Creed in the 1662 prayer book perpetuated this inaccurate theology.[9] He had seen and liked Whiston's Liturgy of the Church of England reduced before its 1713 publication. However, Clarke deviated from Whiston's embrace of the Apostolic Constitutions and favoured changes that did not substantially alter the prayer book's patterns while still expressing an Arian theology.[10]

In his 1724 manuscript of alterations to the 1662 prayer book, Clarke rewrote prayers to redirect them exclusively towards God the Father.[11] Clarke was a friend of Caroline of Ansbach, who later became queen consort of King George II. After Caroline became queen in 1727, Clarke intended to request she push his nomination as a bishop, a position that would allow him to formally revise the prayer book. Had he not declined to sign the Thirty-nine Articles and encountered protests from William Wake, the incumbent Archbishop of Canterbury, over this heterodoxy, historian A. Elliot Peaston believed Clarke might have become the Archbishop of Canterbury.[12] Unable to secure official support for his views, Clarke's altered prayer book went unpublished. However, copies were made and the original manuscript alterations were given to the British Library following his death.[13][note 3]

Clarke's alterations would eventually inspire several revised prayers books for Presbyterian-influenced congregations and become the basis for what historian G. J. Cuming deemed the most influential unofficial revision to the 1662 prayer book.[16] Theophilus Lindsey, then a Presbyterian-minded Church of England vicar at the Church of St Anne, Catterick, acquired a copy of Clarke's altered prayer book made by his brother-in-law and fellow clergyman John Disney.[17] Therein, Lindsey found Clarke's many revisions, including references to the Trinity "slashed out with violent strokes". Lindsey was so impressed with Clarke's work that he intended to introduce the changes to his congregation at Catterick, but ultimately decided against such action as he believed they would in violation of his vows to the Church of England.[18] However, following his resignation from the church and with influence by John Jones's 1749 Free and Candid Disquisitions, Lindsey added further Unitarian alterations to Clarke's work and published them in 1774 as The Book of Common Prayer reformed according to the plan of the late Dr Samuel Clarke.[19] An enlarged edition was published in 1775. While Lindsey used Clarke's name, liturgist Ronald Jasper later argued that little was borrowed from the 1724 alterations in producing the 1774 prayer book and that Lindsey's liturgy was more radical, with influence by William Whiston.[20]

Lindsey's prayer book was utilized by the Dissenter congregation he founded at Essex Street Chapel—the first formally Unitarian church in England—from its first service on 17 April 1774 onward.[21] Lindsey was part of a network of like-minded churchmen, including Joseph Priestley, that had influenced Lindsey's aversion to the unmodified 1662 prayer book before his resignation from the Church of England.[22] Priestley would write in support of Unitarian liturgical worship in his 1783 Forms of Prayer.[23] While Lindsey seems to have approved of Priestley's efforts to produce a paraphrased Bible, Lindsey retained the King James Version and 1662 prayer book's psalter for his revised prayer book on the premise that he was preserving the 1662 prayer book's scriptural foundations while replacing its theology.[24] Lindsey's prayer book, which was repeatedly revised, proved popular with Presbyterians and helped cement the address of all prayers to God the Father as "one of the most tenacious characteristics of Unitarian worship".[25]

English Unitarian attempts to revise the Anglican prayer book continued into the nineteenth century. Lindsey's editions in particular remained a dominant influence in English Unitarian service books.[26] However, some Unitarian liturgies like John Prior Estlin's 1814 General Prayer-Book were derived from the 1662 prayer book independent of Lindsey's work.[27] Despite their departure from Trinitarian orthodoxy, English Unitarian revisions often featured only conservative changes in hopes of limiting division between Unitarians and the Church of England.[28] In 1861, Thomas Sadler and James Martineau published Common Prayer for Christian Worship, initiating a departure from utilizing the Anglican prayer book as the basis of English Unitarian worship. However, some Anglican influences survived within Sadler and Martineau's text and five of the 40 English Unitarian liturgical books published from 1861 until the middle of the next century were derived from the Anglican prayer book.[29][note 4]

Freeman and the King's Chapel liturgy

editIn 1784, Essex Street Chapel congregant William Hazlitt provided a copy of Lindsey's prayer book to his friend James Freeman of King's Chapel in Boston, spurring a Unitarian revision of the prayer book that remains in use there today.[31] Founded in 1686, King's Chapel was the oldest Anglican church in Boston.[32][note 5] As the American Revolutionary War escalated, King's Chapel's Loyalist Anglican minister and much of its congregation fled with the British Army when it evacuated Boston in 1776. The Anglicans who remained permitted members of the Old South Church congregation to use King's Chapel, with the two groups celebrating separately at alternating times in the day.[34] Under this scheme, Freeman—a Harvard graduate and Congregationalist—was invited to serve as a lay reader at King's Chapel in 1782.[35] The congregation's proprietors chose Freeman as pastor on 21 April 1783.[36]

Freeman was initially content with using the 1662 prayer book as modified at Trinity Church.[37][note 6] In the aftermath of the American Revolution, there was broad support for both a new American Anglican church and a local revision to the 1662 prayer book.[39] Simultaneously, there was a rise of Unitarian sentiment across New England congregations, including at King's Chapel.[40] Already, King's Chapel had ceased praying the 1662 prayer book's prescribed prayer for the king and royal family, instead substituting prayers for the president and Congress. Additionally, Freeman's position enabled him to say the Athanasian Creed at his discretion.[41] Hazlitt, who had arrived in Boston from England in search of a preaching position, informed Freeman of Lindsey's prayer book and convinced Freeman and "several respectable ministers" to abandon the ubiquitous Trinitarian doxology.[42][note 7]

At age 24, Freeman pressed King's Chapel to adopt a revised prayer book.[44] On 20 February 1785, the proprietors voted to create a committee composed of seven men to report on Freeman's alterations.[45] Drawing upon Clarke and Lindsey's work, Freeman worked with Hazlitt on a prayer book which was then put to a vote by the proprietor's of King's Chapel.[46] Freeman wrote to his father before the vote, saying that he was optimistic that he had the necessary support but would resign from his position as pastor should the prayer book vote fail.[47] On 19 June, Freeman's prayer book was adopted by a 20–7 majority.[48][note 8] "Thus," Francis William Pitt Greenwood said in his sermon at Freeman's funeral, "the first Episcopal church in New England became the first Unitarian church in the New World."[50][note 9]

The 1785 prayer book's preface held that "no Christian, it is supposed, can take offence at, or find his conscience wounded" by the King's Chapel liturgy, and that "the Trinitarian, the Unitarian, the Calvinist, and the Arminian will read nothing in it which can give him any reasonable umbrage."[53] Despite this, there was dissent and controversy over the liturgy's publication.[54] With Freeman still not ordained, he applied for ordination in the new Anglican Episcopal Church in 1786. This application was rejected by Bishops Samuel Seabury and Samuel Provoost after Freeman refused to assent to the Episcopalians' own prayer book and the Trinitarian theology within it.[55]

The congregation decided to ordain Freeman themselves, devising and performing their own "solemn and appropriate form" in November 1787, with the senior churchwarden performing the laying on of hands on Freeman.[56] This event ended King's Chapel's association with the Episcopal Church.[57] Samuel J. May wrote that Freeman was isolated during his early ministry through his exclusion from the Episcopal Church and poor integration with nearby Congregationalist ministers who were "embarrassed" by Freeman's use of a prayer book and liturgies.[58] Freeman retired from ministry in 1826.[59]

Under the guidance of assistant minister Samuel Cary, a second edition of the liturgy was published in 1811 which included services from other congregations and reintroduced prayers removed in the 1785 edition. Greenwood oversaw three revisions between 1828 and 1841, which sought to improve the prayer book's private devotional functionality and introduced over 100 hymns to the psalter. Theses additions were subsequently removed in the 1918 sixth edition by senior minister Howard N. Brown.[60] This version would remain largely unchanged through 1980,[61] though minister Joseph Barth introduced services from 1955 to 1965 which were likely influenced by his Catholic upbringing.[62] The congregation also borrowed liturgical concepts from the Catholic Church's Second Vatican Council reforms.[63]

In 1980, the vestry voted to create a committee of nine lay members to revise a new prayer book. This revision process took five years, culminating in the current ninth edition in 1986. The congregation is now part of the Unitarian Universalist Association.[64] King's Chapel is described as "Unitarian in theology, Anglican in worship, and congregational in governance,"[65] and its prayer book stands in contrast with the preference for humanist- and non-Christian-inspired forms of radical free worship among modern Unitarians.[66]

Contents

editSince Thomas Cranmer introduced the first Book of Common Prayer in 1549, there have been many editions of the Book of Common Prayer published in more than 200 languages. According to historian David Ney, Cranmer hoped his prayer book would grant the English people "a robustly Trinitarian worship which immersed them in the full counsel of the Word of God".[67] Cranmer drew upon both the medieval Sarum Use and contemporary Lutheran and Calvinist forms in developing the liturgies contained within the Anglican prayer book.[68] The successive editions of the Church of England's prayer books iterated on its contents, which by the 1662 prayer book featured the Holy Communion office, Daily Office, lectionaries, calendar of feasts and fasts, ordinal, psalter, and Thirty-nine Articles. The 1662 prayer book also contained the rites for confirmation, several forms of baptism, and burial.[69] It was from the 1662 prayer book that the Unitarian and other Dissident prayer book traditions found their basis.[70]

Many Unitarian revisions of the Anglican prayer book drew upon Lindsey's editions, mirroring the 1662 prayer book's structure if not always its verbiage. The English Unitarian revisions of the period from 1774 until 1851 demonstrated little evidence that their compilers were learned in liturgics, though their Unitarian theology was strongly expressed. A commonality among Unitarian liturgical texts was their Communion offices which expressed an extreme sacramentarian or memorialist theology of the Eucharist.[71]

Clarke

editClarke's 1724 manuscript of alterations to the 1662 prayer book were generally Unitarian and Nontrinitarian, with all Trinitarian formulae modified or removed.[72] Clarke made these alterations with a pen within his personal copy of the prayer book.[73] The alterations including deleting the Gloria Patri and replacing it with his own doxology that only addressed God the Father. He also rewrote portions of the Litany to direct prayers away from the Holy Spirit towards the Father.[74] The Nicene Creed was replaced with a psalm; the Athanasian Creed was removed.[75] Clarke first proposed his alterations to the baptism office in 1712, leaving the sign of the cross as an option and introducing the 1689 Liturgy of Comprehension's permission that parents might serve as sponsors.[76]

Clarke's ordinal deleted Trinitarian references at the conclusion of prayers. He also adjusted the formulae for the ordinations of priests and bishops, changing the impositions of hands to prayers. The hymn "Come Holy Ghost" in the ordination of priests was supplanted with a psalm, while the wording in the consecratory rite for the episcopate of "fall to Prayer" was made "offer up our Prayers".[77][note 10]

Lindsey

editLindsey's 1774 prayer book, which incorporated both his own and Clarke's alterations to the 1662 prayer book, was tonally Unitarian with some Puritan influence. In order to prevent the interpretation that a priest could forgive sins, the absolution at both Mattins and Evensong are both replaced with the Collect for Purity and the Communion office is rewritten as a prayer for God's forgiveness. The Te Deum, Benedicite, Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis were all removed.[80] Additionally, the prefaces, Athanasian Creed, catechism, ordinal, and some collects were removed.[81] The virgin birth of Jesus was rejected as "unhistorical" and Satan no longer mentioned within the Litany.[82] Like Clarke, Lindsey presumed that ante-Nicene Christians subscribed to Unitarian views, thus preserving the Apostles' Creed in this revision.[83] However, Lindsey eventually removed the Apostles' Creed from his church services in 1789.[84]

Lindsey's prayer book emphasized the Daily Office, drawing upon medieval Catholic practices and establishing non-Eucharistic offices as the norm for Unitarian worship.[85] The Communion office—sans the Prayer of Humble Access, Lord's Prayer, and Prayer of Thanksgiving—was always led by Mattins. Lindsey similarly removed references to sacrifice and the Second Coming. Offices for private baptism, the "Baptism of those of Riper Years", and confirmation were removed and the matrimonial office altered to included a longer exhortation.[86] Some psalms were excised, with Isaac Watts writing most of the 131 hymns and metrical psalms which were added.[87]

While Lindsey's omissions were extensive, they were not entirely unusual among contemporary prayer book abridgments. It was not uncommon for 18th-century English printers trying to keep expenses down to delete material not conducive to devotional usage. Additionally, some of the material removed in the original 1774 revised prayer book were reintroduced in Lindsey's later editions, including within the 1791 edition that brought back offices for adult baptism and ordination as well as a catechism.[88][note 11]

King's Chapel

editThe first edition of the King's Chapel liturgy[note 12] closely followed the amendments within Clarke's prayer book.[91] Freeman's 1785 preface acknowledges that "great assistance hath been derived from the Judicious corrections of the Reverend Mr. Lindsey" and his prayer book revised according to "the truly pious and justly celebrated Doctor Samuel Clarke".[92] The Trinitarian Gloria Patri was deleted, as were the Nicene and Athanasian Creeds.[93] As political considerations, "A Prayer for the King's Majesty" is replaced by "A Prayer for the Congress of the United States" and the prayer for High Court of Parliament became "A Prayer for the Great and General Court", with kingdom supplanted by Commonwealth in the latter.[94] Freeman's low churchmanship and the congregation's egalitarianism saw minister replace priest and ordinance replace sacrament. A catechism written by Priestley, who relocated to preach in Pennsylvania towards the end of his life, was included for teaching children.[95]

Unlike Lindsey's prayer book, the King's Chapel prayer book retained the Benedicite due to its biblical basis in 2 Corinthians. The text also differed in keeping an altered Te Deum, as well as maintaining both the Venite and the General Confession's "there is no health in us." Freeman, writing to Lindsey in 1786, described that "Some defects and improprieties" were retained so that the King's Chapel congregation might "omit the most objectionable parts of the old service, the Athanasian prayers." According to King Chapel minister Carl Scovel, Freeman's 1785 liturgy appears "quite traditional" to the modern eye, with the Sunday offices and lectionary largely similar to those of the 1662 prayer book.[96]

Greenwood reported that the first edition of the King's Chapel liturgy was immediately published after its approval and used until 1811, when it was supplanted with the amended second edition. Greenwood, replacing Freeman as pastor, guided the next three revisions;[97] the 1828 third edition added further changes that were themselves unchanged in the 1831 fourth edition, the latter of which added family services, prayers, and devotional hymns.[98] Greenwood also helmed a fifth edition in 1841. Over the course of his revisions, Greenwood introduced over 100 hymns to the psalter including those by Watts as well as Charles and John Wesley.[99][note 13]

In the 1918 sixth edition, Brown removed almost all of Greenwood's additions.[101] In the same edition, Brown introduced the Didache—a previously lost early Christian text rediscovered in 1900–to the prayer book, though Scovel believed this addition was never used during King's Chapel services. The 1925 seventh edition differed very little from the sixth, with minor alterations to language within the Communion service. Though not formally published, a notional "eighth edition" developed between 1955 and 1965 under minister Joseph Barth, introducing additional services such as the imposition of ashes on Ash Wednesday. Barth and his services were likely influenced by his Catholic upbringing.[102]

The latter forms remained in use through 1980, by which time the minister utilized the Common Lectionary. This lectionary would be formally integrated into the 1986 ninth edition,[note 14] as would Evensong and several accreted services including midweek prayers. The entire psalter according to the King James Version with minor Revised Standard Version-based changes and more than 30 hymns were also included in this revision. Most of the 1662 prayer book's language was retained, but the revising committee made "modest changes" to remove male generic terms.[104]

Influence on non-Unitarian liturgies

editWhile few ministers followed Lindsey in resigning from the Church of England, many shared his theology and considered his 1774 prayer book a modernization of the 1662 liturgy.[105] Through the 19th century, new editions of Lindsey's prayer book and derivatives were printed, with the Athanasian Creed remaining their primary objection.[106] With Lindsey's prayer book as inspiration, 15 liturgies based on the 1662 prayer book were published in England between 1792 and 1854 with similar Unitarian "modernizations".[107][note 15] Peaston assessed these liturgies as "remarkable for the rationality of their thought, and the tediousness of their expression. They would seem indeed to have been in the tradition of John Locke."[109]

John Wesley created his own revision of the 1662 prayer book in 1784 for American Methodists entitled The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America. Wesley, who considered the 1662 prayer book strong in its "solid, scriptural, rational Piety", is known to have been interested in producing a revised prayer book since 1736.[110] Clarke, Lindsey, Jones, and Whiston are among the prayer book revisionists that Wesley explicitly named in his personal writings and Wesley was familiar with Lindsey through the Feathers Tavern Association.[111] While Wesley never said whether he read Lindsey's prayer book, the 1784 Sunday Service contained many parallels with the 1774 revision,[112] including omitting a confirmation rite.[113]

Episcopal Church

editAfter approving the 1785 liturgy, members of King's Chapel held a measure of expectation that other American Anglican congregations would follow their lead in issuing their own revised prayer books.[114] Rector at Trinity Church Samuel Parker had pressed for liturgical changes beyond those related to politics at the Middletown Convocation in August 1785, with Seabury agreeing that some of the liturgical changes adopted at Trinity Church would be part of the new prayer book.[115] The Unitarians of King's Chapel hoped that this new prayer book would match their theology, though it is unclear if the Middletown Convocation had access to the chapel's prayer book.[116] The Episcopal Church authorized a committee with broad powers to revise a prayer book.[117] This committee included William White, a Pennsylvanian clergy who favoured Locke's thought.[118] The adoption of Freeman's liturgy at King Chapel spurred White to privately acknowledged the King's Chapel congregation's actions as irregular, with White defending Trinitarian orthodoxy but also admitting his own desires that the Episcopal Church's revised prayer book remove non-scriptural doctrines and creeds.[119]

The Episcopal Church committee published their proposed prayer book on 1 April 1786.[120] The text reflected English Deist influence and featured substantial Unitarian leanings.[121] This proposed prayer book removed the Nicene and Athanasian Creeds,[122] omitted the "He descended into hell" from the Apostles' Creed, and reduced praise to the Trinity.[123] While the proposed Episcopal book was certainly a more orthodox, conservative revision than the King's Chapel prayer book and featured fewer omissions than Wesley's liturgy, Wesley's work was more explicit in expressing Trinitarian doctrine.[124] Concurring with Seabury and Edward Bass, Parker took a hardline position against the 1786 proposed prayer book's "irregularly made revisions"; historian Paul V. Marshall attributes this to Parker's familiarity with the King's Chapel prayer book.[125] The 1786 proposed text did not last and a more conservative prayer book revision was approved by the General Convention in 1789 and introduced in 1790.[126][note 16]

See also

edit- Dr Williams's Library, a British collection which includes many Unitarian and Nonconformist revised editions of the Anglican prayer book

- Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813, a British parliamentary act granting toleration of Unitarian worship

- Joseph Priestley and Dissent, on Priestley's involvement in English Dissent and Unitarianism

- Savoy Conference, the 1661 summit that culminated in the 1662 prayer book

Notes

edit- ^ Stephen's 1696 text was entitled Liturgies of the Ancients represented, as near as well be, in English forms, with a Preface concerning the Restitution of the most Solemn Part of the Christian Worship in the Holy Eucharist, to its Integrity, and just Frequency of Celebration. Whiston, who was more liturgically sophisticated than Stephens, published The Liturgy of the Church of England, reduced nearer to the Primitive Standard in 1713.[2]

- ^ Despite Scovel giving the date of original publication for The Scriptural Doctrine of the Trinity as 1719,[5] it is generally given as 1712.[6] Clarke was regularly involved in philosophical and doctrinal discussion, particularly Newtonianism through his association with Isaac Newton. Despite public retracting his views and ceasing writing on the Trinity under threat of censure by Convocation, Clarke appears to have privately continued rejecting Trinitarianism.[7]

- ^ Clarke died in 1729. His prayer book was donated to the British Library by his son, also named Samuel Clarke, in 1768.[14] John Jones, a disciple of Clarke, anonymously published Free and Candid Disquisitions in 1749. Here, Jones called on Convocation to approve a revised prayer book Dissenters could support but encouraged unofficial revisions should official channels fail.[15]

- ^ Sadler had previously ministered at Little Portland Street Chapel, a Unitarian congregation that utilized a liturgy derived from Lindsey's recension.[30]

- ^ King's Chapel was also known as First Episcopal Church.[33]

- ^ Trinity Church was the only Anglican congregation in Boston to remain open during the whole American Revolutionary War. To "preserve public tranquility", the liturgy was modified to excise references to the British king.[38]

- ^ Freeman's theological shift was unlike many of his New England Congregationalist contemporaries who approached Unitarianism through Arianism. Freeman, in regular correspondence with English Unitarians, would first adopt Socinianism before fully embracing Unitarian theology.[43]

- ^ Greenwood notes that three of the opposing votes came from proprietors who had worshipped exclusively at Trinity Church since 1776.[49]

- ^ Freeman's 1787 ordination has also been appraised as the "formal beginning of Unitarianism in New England."[51] Peaston also held that King's Chapel was the first New World Unitarian congregation.[52]

- ^ Disney's copy of Clarke's work was held in the British Museum's collection by 1949.[78] Both Jasper and Paul F. Bradshaw refer to a manuscript copy in the British Library for their details of Clarke's alterations.[79]

- ^ Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Unitarian Neville Chamberlain utilized the phrase "Peace for our time", a modified form of the phrase "peace in our time" which appears in the 1662 prayer book. It is possible that his familiarity with the phrase came from its retention within Lindsey's recension of the Book of Common Prayer and modified appearance within later Unitarian service books.[89]

- ^ The title page of the 1785 prayer book gave the full title as A Liturgy Collected Principally from the Book of Common Prayer for The Use of the First Episcopal Church in Boston; Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David and states it was printed by Peter Edes of State Street.[90]

- ^ The title of an 1844 psalter, listed in the 38th edition, is given as A Collection of Psalms and Hymns for Christian Worship.[100]

- ^ The full title of the 1986 ninth edition King's Chapel prayer book is Book of Common Prayer According to the Use in King's Chapel.[103]

- ^ In total, 54 liturgies were published in England between 1713 and 1854. The majority were from Nonconformists and some were formulated independently from the 1662 prayer book. While some of the liturgies share of their primary objectives with those of Clarke and Lindsey, others were focused on pan-Protestant "comprehension" through the excision of "Romanism".[108]

- ^ As the Episcopal Church hoped that English bishops might consecrate some of its clergymen, the English episcopates' staunch opposition to the proposed 1786 American prayer book proved decisive in its ultimate rejection.[127]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Maxwell 1949, pp. 16–17, 31–32

- ^ Maxwell 1949, p. 31

- ^ Maxwell 1949, pp. 17–18

- ^ Peaston 1959; Long 1986, p. 513

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 214

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 1911; Vailati & Yenter 2021; Marshall 2004, p. 112

- ^ Wigelsworth 2003; Westerfield Tucker 1996, p. 244

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 214; Encyclopædia Britannica 1911

- ^ Vailati & Yenter 2021

- ^ Jasper 1989, p. 14

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 214; Peaston 1959

- ^ Peaston 1959; Jasper 1989, p. 15

- ^ Jasper 1989, p. 15

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography 1887

- ^ Jasper 1989, p. 15

- ^ Peaston 1959; Cuming 1969, p. 178

- ^ Jasper 1989, p. 17; Spinks 2006, p. 519; Maxwell 1949, p. 33

- ^ Ney 2021, pp. 149–150

- ^ Cuming 1969, pp. 177–178; Long 1986, p. 514; Westerfield Tucker 1996, p. 244

- ^ Jasper 1989, p. 17

- ^ Long 1986, p. 514; Ney 2021, p. 150

- ^ Ney 2021, p. 152

- ^ Peaston 1940, p. 83

- ^ Ney 2021, p. 152

- ^ Long 1986, p. 514

- ^ Maxwell 1949, p. 20

- ^ Ledger-Lomas 2013, p. 214

- ^ Ledger-Lomas 2013, pp. 211–212

- ^ Ledger-Lomas 2013, p. 214

- ^ Ledger-Lomas 2013, p. 222

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 214; Harvard Square Library

- ^ Chorley 1930, p. 60; Scovel 2006, p. 214

- ^ Peaston 1940, p. 84

- ^ Harvard Square Library

- ^ Independent Country, Independent Church; Scovel 2006, p. 214

- ^ Greenwood 1833, p. 135

- ^ Chorley 1930, p. 60

- ^ Peabody 1980

- ^ Suter & Cleveland 1949, p. 23

- ^ Chorley 1930, p. 60

- ^ Scovel 2006, pp. 214–215; Greenwood 1833, p. 136

- ^ "History of Reforms"

- ^ Dartmouth

- ^ "The History of the Prayer Book"

- ^ Greenwood 1833, p. 138

- ^ "The History of the Prayer Book"; Wolff 1921

- ^ Harvard Square Library

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 214

- ^ Greenwood 1833, p. 138

- ^ Harvard Square Library

- ^ Wolff 1921

- ^ Peaston 1940, p. 22

- ^ Chorley 1930, p. 62

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 215

- ^ Harvard Square Library

- ^ Greenwood 1833, pp. 140–141

- ^ Chorley 1930, p. 62

- ^ Harvard Square Library

- ^ Harvard Library

- ^ "The History of the Prayer Book"

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 216

- ^ "The History of the Prayer Book"

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 216

- ^ Scovel 2006, pp. 216–217

- ^ Wakefield 1985, p. 17

- ^ Long 1986, p. 513

- ^ Ney 2021, p. 136

- ^ Maxwell 1949, p. 6

- ^ Ney 2021, pp. 137, 152–153

- ^ Ney 2021, p. 136

- ^ Maxwell 1949, p. 20

- ^ Cuming 1969, p. 176

- ^ Ney 2021

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 214

- ^ Cuming 1969, p. 176; Jasper 1989, p. 14

- ^ Jasper 1989, p. 15

- ^ Bradshaw 1971, p. 106

- ^ Maxwell 1949, p. 33

- ^ Jasper 1989, p. 14; Bradshaw 1971, p. 106

- ^ Cuming 1969, p. 178

- ^ Ney 2021, pp. 152–153

- ^ Long 1986, p. 514

- ^ Ney 2021, p. 155

- ^ Marshall 2004, p. 144

- ^ Long 1986, p. 514

- ^ Cuming 1969, p. 179

- ^ Marshall 2004, p. 117

- ^ Ney 2021, p. 153

- ^ Pulbrook 2013

- ^ Chorley 1930, p. 61

- ^ Harvard Square Library

- ^ Chorley 1930, p. 61

- ^ Chorley 1930, p. 62

- ^ Peaston 1940, p. 85

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 215

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 215

- ^ "The History of the Prayer Book"

- ^ Greenwood 1833, p. 139

- ^ "The History of the Prayer Book"

- ^ A Collection of Psalms and Hymns for Christian Worship

- ^ Scovel 2006, p. 216

- ^ "The History of the Prayer Book"

- ^ King's Chapel 1986

- ^ Scovel 2006, pp. 216–217

- ^ Spinks 2006, p. 519

- ^ Cuming 1969, pp. 192–193

- ^ Westerfield Tucker 1996, p. 244

- ^ Calcote 1977, p. 279

- ^ Spinks 2006, p. 519

- ^ Westerfield Tucker 1996, p. 230

- ^ Westerfield Tucker 1996, pp. 234, 244

- ^ Jasper 1989, p. 19

- ^ Westerfield Tucker 1996, p. 244

- ^ Spinks 2006, p. 519

- ^ Marshall 2004, pp. 126–129

- ^ Suter & Cleveland 1949, p. 23; Marshall 2004, p. 142

- ^ Pullan 1901, pp. 285–286

- ^ Calcote 1977, p. 289; Marshall 2004, p. 14

- ^ Calcote 1977, p. 289

- ^ Pullan 1901, pp. 285–286

- ^ Pullan 1901, pp. 285, 299

- ^ Greenwood 1833, p. 136

- ^ Pullan 1901, pp. 285–286

- ^ Marshall 2004, pp. 160–161

- ^ Marshall 2004, pp. 144–145

- ^ Pullan 1901, pp. 285–286; Suter & Cleveland 1949, p. 23

- ^ Peaston 1940, p. 22

Primary sources

edit- Book of Common Prayer According to the Use in King's Chapel. Boston: King's Chapel. 1986.

- Greenwood, F.W.P., ed. (1844). A Collection of Psalms and Hymns for Christian Worship (38th ed.). Boston: Charles J. Hendee and Jenks & Palmer.

Secondary sources

edit- Bradshaw, Paul F. (1971). The Anglican Ordinal: Its History and Development From the Reformation to the Present Day. Alcuin Club Collections No. 53. London: Alcuin Club, Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge.

- "The Book of Common Prayer: History of Reforms". Independent Country, Independent Church: American Independence, James Freeman, and King’s Chapel’s 1780s Theological Revolution. Boston: King's Chapel. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- Benowitz, June Melby (2017). Encyclopedia of American Women and Religion. Vol. I. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC. ISBN 978-1-4408-4822-3.

- Calcote, A. Dean (September 1977). "The Proposed Prayer Book Of 1785". Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church. 46 (3). Historical Society of the Episcopal Church: 275–295. JSTOR 42973565.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Chorley, E. Clowes (1930). The New American Prayer Book: Its History and Contents. New York City: The Macmillan Company.

- Cuming, G. J. (1969). A History of Anglican Liturgy (1st ed.). London: St. Martin's Press, Macmillan Publishers.

- "Freeman, James (1759–1835)". Cambridge, MA: Harvard Square Library, First Parish in Cambridge. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- Greenwood, Francis William Pitt (1833). A History of King's Chapel, in Boston, the First Episcopal Church in New England: Comprising Notices of the Introduction of Episcopacy Into the Northern Colonies. Boston: Carter, Hendee & Company.

- "The History of the Prayer Book". Boston: King's Chapel. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- Independent Country, Independent Church: American Independence, James Freeman, and King's Chapel's 1780s Theological Revolution. Boston: King's Chapel. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- "Freeman, James, 1759–1835". Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- Jasper, R.C.D. (1989). The Development of the Anglican Liturgy, 1662–1980. London: Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge.

- Ledger-Lomas, Michael (September 2013). "Unitarians and the Book of Common Prayer in Nineteenth-Century Britain". Studia Liturgica. 43 (2). SAGE Publications: 211–228. doi:10.1177/003932071304300202. S2CID 165907637.

- Long, A.J. (1986). "Unitarian Worship". In Davies, J.G. (ed.). The New Westminster Dictionary of Liturgy and Worship. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. ISBN 0-664-21270-0.

- Marshall, Paul Victor (2004). One, Catholic, and Apostolic: Samuel Seabury and the Early Episcopal Church. New York City: Church Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89869-447-7.

- Maxwell, William D. (1949). The Book of Common Prayer and the Worship of the Non-Anglican Churches (PDF). Friends of Dr. William's Library. Oxford: Oxford University Press – via Project Canterbury.

- Ney, David (June 2021). "The Genesis of the Unitarian Church and the Book of Common Prayer". Anglican and Episcopal History. 90 (2). Austin, TX: Historical Society of the Episcopal Church. ProQuest 2557870193 – via ProQuest.

- Peabody, James Bishop (1980). "Historical Introduction". In Oliver, Andrew; Peabody, James Bishop (eds.). The Records of Trinity Church, Boston 1728–1830. Publications of The Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Vol. LV. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

- Peaston, A.. Elliott (1940). The Prayer Book Reform Movement in the XVIIIth Century. Oxford: Basil Blackwell & Mott Ltd. – via Internet Archive.

- Peaston, A.. E. (1 January 1959). "The Revision of the Prayer Book by Dr. Samuel Clarke". Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society. 12 (1): 27 – via ProQuest.

- Pulbrook, Martin (23 October 2013). "Peace in our time". Irish Times. p. 15. ProQuest 1445393848 – via ProQuest.

- Pullan, Leighton (1901). Newbolt, W.C.E.; Stone, Darwell (eds.). The History of the Book of Common Prayer. The Oxford Library of Practical Theology (3rd ed.). London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Scovel, Carl (2006). "King's Chapel and the Unitarians". In Hefling, Charles; Shattuck, Cynthia (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Book of Common Prayer: A Worldwide Survey. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-529762-1.

- Spinks, Bryan D. (2006). "Anglicans and Dissenters". In Wainwright, Geoffrey; Westerfield Tucker, Karen B. (eds.). The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 519. ISBN 978-0-19-513886-3.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1887). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 10. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- "Student mathematical textbook of James Freeman, 1774: James Freeman's manuscript, September 25, 1774". Colonial North America at Harvard Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Library. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- Suter, John Wallace; Cleveland, George Julius (1949). The American Book of Common Prayer: Its Origin and Development. New York City: Oxford University Press.

- Vailati, Ezio; Yenter, Timothy (Winter 2021). "Samuel Clarke". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Wakefield, Dan (22 December 1985). "Returning to Church". New York Times – via New York Times Archives.

- Westerfield Tucker, Karen B. (July 1996). "John Wesley's Prayer Book Revision: The Text in Context" (PDF). Methodist History. 34 (4). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2022 – via General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church.

- Wigelsworth, Jeffery R. (2001–2003). "The Sleeping Habits of Matter and Spirit: Samuel Clarke and Anthony Collins on the Immortality of the Soul". Past Imperfect. 9. University of Alberta: 5. doi:10.21971/P7D01D.

- Wolff, Samuel Lee (1921). Trent, William Peterfield; Erskine, John; Sherman, Stuart P.; Van Doren, Carl (eds.). . Cambridge History of American Literature. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press – via Wikisource.

External links

edit- Lindsey, Theophilus (1774). The Book of Common Praywr Reformed According to the Plan of the Late Dr. Samuel Clarke, Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David. London. Lindsey's revision of Clarke's prayer book.

- Devotional Offices for Public Worship. Collected from Various Services, in Use Among Protestant Dissenters. To which are Added, Two Services, Chiefly Selected from the Book of Common Prayer. Salisbury: C. Collins. 1794. An English Nonconformist prayer book revision that post-dates Lindsey's prayer book but was not in Lindsey's tradition.

- First edition of the King's Chapel Liturgy and Psalter. (1785). Boston: Peter Edes. Scanned copies of the first King's Chapel prayer book and psalter.

Further reading

edit- Chinkes, Margaret Barry (1991). James Freeman and Boston's Religious Revolution. Glade Valley, NC: Glade Valley Books. A history of Freeman and King's Chapel that Paul V. Marshall appraised as "a carefully researched monograph".

- Foote, Henry Wilder; Clarke, James Freeman (1885). The Centenary of the King's Chapel Liturgy. Boston: Press of George H. Ellis. A history of King's Chapel by members of the congregation.

- Peaston, Alexander Elliott (1 October 1976). "The Unitarian liturgical tradition". Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society. 12 (2). London: Unitarian Historical Society – via ProQuest. A survey of Unitarian worship including prayer book revisions.