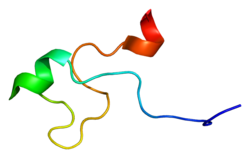

Tristetraprolin (TTP), also known as zinc finger protein 36 homolog (ZFP36), is a protein that in humans, mice and rats is encoded by the ZFP36 gene.[5][6] It is a member of the TIS11 (TPA-induced sequence) family, along with butyrate response factors 1 and 2.[7]

TTP binds to AU-rich elements (AREs) in the 3'-untranslated regions (UTRs) of the mRNAs of some cytokines and promotes their degradation. For example, TTP is a component of a negative feedback loop that interferes with TNF-alpha production by destabilizing its mRNA.[8] Mice deficient in TTP develop a complex syndrome of inflammatory diseases.[8]

Interactions

editZFP36 has been shown to interact with 14-3-3 protein family members, such as YWHAH,[9] and with NUP214, a member of the nuclear pore complex.[10]

Regulation

editPost-transcriptionally, TTP is regulated in several ways.[7] The subcellular localization of TTP is influenced by interactions with protein partners such as the 14-3-3 family of proteins. These interactions and, possibly, interactions with target mRNAs are affected by the phosphorylation state of TTP, as the protein can be posttranslationally modified by a large number of protein kinases.[7] There is some evidence that the TTP transcript may also be targeted by microRNAs, such as miR-29a.[7]

References

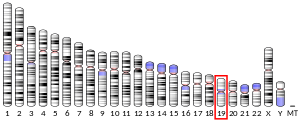

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000128016 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000044786 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ DuBois RN, McLane MW, Ryder K, Lau LF, Nathans D (Dec 1990). "A growth factor-inducible nuclear protein with a novel cysteine/histidine repetitive sequence". J Biol Chem. 265 (31): 19185–91. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)30642-7. PMID 1699942.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: ZFP36 zinc finger protein 36, C3H type, homolog (mouse)".

- ^ a b c d Sanduja S, Blanco FF, Dixon DA (2011). "The roles of TTP and BRF proteins in regulated mRNA decay". Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2 (1): 42–57. doi:10.1002/wrna.28. PMC 3030256. PMID 21278925.

- ^ a b Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ (August 1998). "Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin". Science. 281 (5379): 1001–5. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.1001C. doi:10.1126/science.281.5379.1001. PMID 9703499.

- ^ Johnson BA, Stehn JR, Yaffe MB, Blackwell TK (May 2002). "Cytoplasmic localization of tristetraprolin involves 14-3-3-dependent and -independent mechanisms". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (20): 18029–36. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110465200. PMID 11886850.

- ^ Carman JA, Nadler SG (March 2004). "Direct association of tristetraprolin with the nucleoporin CAN/Nup214". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 315 (2): 445–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.080. PMID 14766228.

Further reading

edit- Blackshear PJ (2003). "Tristetraprolin and other CCCH tandem zinc-finger proteins in the regulation of mRNA turnover". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30 (Pt 6): 945–52. doi:10.1042/bst0300945. PMID 12440952.

- Carrick DM, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ (2005). "The tandem CCCH zinc finger protein tristetraprolin and its relevance to cytokine mRNA turnover and arthritis". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 6 (6): 248–64. doi:10.1186/ar1441. PMC 1064869. PMID 15535838.

- Taylor GA, Lai WS, Oakey RJ, et al. (1991). "The human TTP protein: sequence, alignment with related proteins, and chromosomal localization of the mouse and human genes". Nucleic Acids Res. 19 (12): 3454. doi:10.1093/nar/19.12.3454. PMC 328350. PMID 2062660.

- Lai WS, Stumpo DJ, Blackshear PJ (1990). "Rapid insulin-stimulated accumulation of an mRNA encoding a proline-rich protein". J. Biol. Chem. 265 (27): 16556–63. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)46259-4. PMID 2204625.

- Taylor GA, Thompson MJ, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ (1995). "Phosphorylation of tristetraprolin, a potential zinc finger transcription factor, by mitogen stimulation in intact cells and by mitogen-activated protein kinase in vitro". J. Biol. Chem. 270 (22): 13341–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.22.13341. PMID 7768935.

- Heximer SP, Forsdyke DR (1993). "A human putative lymphocyte G0/G1 switch gene homologous to a rodent gene encoding a zinc-binding potential transcription factor". DNA Cell Biol. 12 (1): 73–88. doi:10.1089/dna.1993.12.73. PMID 8422274.

- Huebner K, Druck T, LaForgia S, et al. (1993). "Chromosomal localization of four human zinc finger cDNAs". Hum. Genet. 91 (3): 217–22. doi:10.1007/BF00218259. PMID 8478004. S2CID 35926610.

- Lai WS, Carballo E, Thorn JM, et al. (2000). "Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA. Binding of tristetraprolin-related zinc finger proteins to Au-rich elements and destabilization of mRNA". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (23): 17827–37. doi:10.1074/jbc.M001696200. PMID 10751406.

- Dintilhac A, Bernués J (2002). "HMGB1 interacts with many apparently unrelated proteins by recognizing short amino acid sequences". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (9): 7021–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108417200. hdl:10261/112516. PMID 11748221.

- Lai WS, Kennington EA, Blackshear PJ (2002). "Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA: non-binding tristetraprolin mutants exert an inhibitory effect on degradation of AU-rich element-containing mRNAs". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (11): 9606–13. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110395200. PMID 11782475.

- Johnson BA, Stehn JR, Yaffe MB, Blackwell TK (2002). "Cytoplasmic localization of tristetraprolin involves 14-3-3-dependent and -independent mechanisms". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (20): 18029–36. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110465200. PMID 11886850.

- Brooks SA, Connolly JE, Diegel RJ, et al. (2002). "Analysis of the function, expression, and subcellular distribution of human tristetraprolin". Arthritis Rheum. 46 (5): 1362–70. doi:10.1002/art.10235. PMID 12115244.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916899M. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Amann BT, Worthington MT, Berg JM (2003). "A Cys3His zinc-binding domain from Nup475/tristetraprolin: a novel fold with a disklike structure". Biochemistry. 42 (1): 217–21. doi:10.1021/bi026988m. PMID 12515557.

- Yu H, Stasinopoulos S, Leedman P, Medcalf RL (2003). "Inherent instability of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 mRNA is regulated by tristetraprolin". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (16): 13912–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M213027200. PMID 12578825.

- Sawaoka H, Dixon DA, Oates JA, Boutaud O (2003). "Tristetraprolin binds to the 3'-untranslated region of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA. A polyadenylation variant in a cancer cell line lacks the binding site". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (16): 13928–35. doi:10.1074/jbc.M300016200. PMID 12578839.