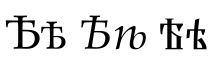

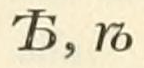

Yat or jat (Ѣ ѣ; italics: Ѣ ѣ) is the thirty-second letter of the old Cyrillic alphabet. It is usually romanized as E with a haček: Ě ě.

There is also another version of yat, the iotated yat (majuscule: ⟨Ꙓ⟩, minuscule: ⟨ꙓ⟩), which is a Cyrillic character combining a decimal I and a yat. There was no numerical value for this letter and it was not in the Glagolitic alphabet. It was encoded in Unicode 5.1 at positions U+A652 and U+A653.

Usage

editYat represented a Common Slavic long vowel, usually notated as ⟨ě⟩. It is generally believed to have represented the sound /æ/ or /ɛ/, like the pronunciation of ⟨a⟩ in "cat" or ⟨e⟩ in "egg", which was a reflex of earlier Proto-Slavic */ē/ and */aj/. That the sound represented by yat developed late in the history of Common Slavic is indicated by its role in the Slavic second palatalization of the Slavic velar consonants.

The Glagolitic alphabet contained only one letter for both yat ⟨ѣ⟩ and the Cyrillic iotated a ⟨ꙗ⟩.[1] According to Kiril Mirchev, this meant that ⟨a⟩ after ⟨i⟩ in the Thessaloniki dialect (which served as a basis for Old Church Slavonic) mutated into a wide vowel that resembled or was the same as yat (/æ/).[2]

To this day, the most archaic Bulgarian dialects, i.e., the Rup and Moesian dialects feature a similar phonetic change where /a/ after iota and the formerly palatal consonants ⟨ж⟩ (/ʒ/), ⟨ш⟩ (/ʃ/) and ⟨ч⟩ (/t͡ʃ/) becomes /æ/, e.g. стоях [stoˈjah] -> стойêх [stoˈjæh] ("(I) was standing"), пияница [piˈjanit͡sɐ] -> пийêница [piˈjænit͡sɐ] ("drunkard"), жаби [ˈʒabi] -> жêби [ˈʒæbi] ("frogs"), etc.[2] Dialects that still feature this phonetic change include the Razlog dialect, the Smolyan dialect, the Hvoyna dialect, the Strandzha dialect, individual subdialects in the Thracian dialect, the Shumen dialect, etc.[3][4]

This problem did not exist in the Cyrillic alphabet, which had two separate letters for yat and iotated a, ⟨ѣ⟩ and ⟨ꙗ⟩. Any subsequent mix-ups of yat and iotated a and/or other vowels in Middle Bulgarian manuscripts are owing to the ongoing transformation of the Bulgarian vowel and consonant system in the Late Middle Ages.[5]

An extremely rare "iotated yat" form ⟨ꙓ⟩ also exists, documented only in Svyatoslav's Izbornik from 1073.

Standard reflexes

editIn various modern Slavic languages, yat has reflected into various vowels. For example, the Proto-Slavic root *bělъ "white" became:

- бел /bʲel/ in Standard Russian (dialectal /bʲal/, /bʲijel/ or even /bʲil/ in some regions)

- біл /bʲil/ in Ukrainian and Rusyn

- бел /bʲel/ in Belarusian

- бял /bʲal/ - бели /beli/ in Bulgarian (бел /bel/ - бели in Western dialects)

- бел /bel/ in Macedonian

- beo / beli in the standard Serbian Ekavian variant of Serbo-Croatian (genitive bela / belog(a))

- bil / bili in Ikavian Serbo-Croatian

- bijel / bijeli in the standard Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian Ijekavian variants of Serbo-Croatian (genitive bijela / bijelog(a))

- bél in Slovenian

- biały in Polish

- bílý in Czech

- biely in Slovak.

Other reflexes

editOther reflexes of yat exist; for example:

- Proto-Slavic telěga / телѣга became taljige (таљиге; ѣ > i reflex) in Serbo-Croatian.

- Proto-Slavic orěhъ / орѣхъ became orah (орах; ѣ > a reflex) in Serbo-Croatian.

Confusion with other letters

editDue to these reflexes, yat no longer represented an independent phoneme but an already existing one, represented by another Cyrillic letter. As a result, children had to memorize by rote whether or not to write yat. Therefore, the letter was dropped in a series of orthographic reforms: in Serbian with the reform of Vuk Karadžić, in Ukrainian-Ruthenian with the reform of Panteleimon Kulish, later in Russian and Belarusian with the Bolshevik reform in 1918,[6] and in Bulgarian and Carpathian dialects of Ruthenian language as late as 1945.

The letter is no longer used in the standard modern orthography of any of the Slavic languages written with the Cyrillic script, but survives in Ukrainian (Ruthenian) liturgical and church texts of Church Slavonic in Ruthenian (Ukrainian) edition and in some written in the Russian recension of Church Slavonic. It has, since 1991, found some favor in advertising to deliberately invoke an archaic or "old-timey" style.

Bulgarian

editThe open articulation of yat (as /æ/ or ja) and the reflexes of Proto-Slavic *tj/*ktĭ/*gtĭ and *dj as ⟨щ⟩ (ʃt) and ⟨жд⟩ (ʒd) have traditionally been considered the two most distinctive phonetic features of Old Bulgarian.[7][8] Based on

- the preserved articulation of yat as /æ/ in the remote eastern Albanian villages of Boboshticë and Drenovë;[9][10][11][12]

- preserved archaic Slavic toponyms in southern and eastern Albania, Thessaly and Epirus featuring ia, ea or a in yat's etymological place, e.g., Δρυάνιστα [ˈdrianista] or Δρυανίτσα [drianˈit͡sa] (renamed Moschopotamos in 1926) from дрѣнъ, "cornel-tree" (see also Dryanovo); Λιασκοβέτσι [liaskovet͡si] (renamed el:Λεπτοκαρυά Ιωαννίνων in 1927) from лѣска, "hazel" (see also Lyaskovets); Labovë e Kryqit and Labovë e Madhe from хлѣбъ, "bread" (see also Hlyabovo), etc.;[8][13]

- the consistent etymological use of ⟨ѣ⟩ at the Ohrid Literary School until the mid-1200s;[14]

- the use of ia, ea or a in yat's etymological place in a number of toponyms in a 1019 Greek-language charter by Byzantine emperor Basil II "the Bulgar Slayer" relating to the newly created Theme of Bulgaria, e.g., Πριζδριάνα [prizdriˈana] for Приздрѣнъ (Prizren); Τριάδιτζα [triˈadit͡sa] for С(т)рѣдьць (Sofia); Πρίλαπον [ˈprilapon] for Прилѣпъ (Prilep); Δεάβολις [deˈabolis] for the medieval fortress of Дѣволъ (Devol, now in eastern Albania); Πρόσακου [ˈprosakon] for the medieval fortress of Просѣкъ (Prosek), etc.;[13][15]

- the use of ea or a in yat's etymological place in a number of local toponyms in the area of modern-day Strumica in a 1152 Greek-language charter by Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos, relating to the Holy Mother of God monastery in Veljusa, e.g., Λεασκοβίτζα [leaskoˈvit͡sa] for Лѣсковица (Лѣсковьць), Λεαπίτζα [leaˈpit͡sa] for Лѣпица, Δράνοβου [ˈdranovon] for Дрѣново, Μπρεασνίκ [breasˈnik] for Брѣзникъ;[13][16]

- the 16th-century Greek-Bulgarian lexicon from Bogatsko in southwestern Macedonia written in Greek letters, which featured ia in yat's etymological place, e.g., μλιακο, mliako ("milk"); ζελιαζo, želiazo ("iron"); βιατρο, viadro ("pale"); βριατενo, vriateno ("spindle"); πoβιασμo, poviasmo ("distaff"); βιαζτi, viaždi ("eyebrows"); κoλιανo, koliano ("knee"); νεβιαστα, neviasta ("bride"), ριακα, riaka ("river"), βιατερ, viater ("wind"), etc., indicating that the Kostur dialect was still yakavian at the time;[13][17][18] etc. etc.

the entire areas of modern Bulgarian and Macedonian are assumed to be have been ѣkavian/yakavian until the Late Middle Ages.[19][20]

In addition to the replacement of ⟨ꙗ⟩ with ⟨ѣ⟩ in a number of Old and Middle Bulgarian Cyrillic manuscripts—reflecting the mutation of iotated a into /æ/, the opposite process of mutation of yat into palatalised consonant + /a/ was also underway. The process affected primarily yat in stressed syllables followed by hard consonant, with multiple examples present in manuscripts from both West and East, e.g. the Grigorovich Prophetologion of the late 1100s (e.g., тꙗло instead of тѣло, "body"), the Tarnovo Gospel of 1273 (e.g, тꙗхъ instead of тѣхъ, "them"), the Strumitsa Apostle of the mid-1200s (e.g., прꙗмѫдро instead of прѣмѫдро, "all-wise"), etc.[21][22]

However, the most certain proof of yakavian pronunciation of ⟨ѣ⟩—and another confirmation that currently Ekavian dialects used to be Yakavian in the Middle Ages—comes from the use of hardened consonsant + a in yat's etymological place. While individual examples of hardened ⟨с⟩ (/s/) or ⟨р⟩ (/r/) + ⟨а⟩ can be found even in Old Bulgarian manuscripts, the mutation is most consistent after hardened ⟨ц⟩ (/t͡s/) and ⟨ꙃ⟩ (/d͡z/) in Middle Bulgarian manuscripts. Thus, the Strumitsa Apostle, for example, features hosts of examples, e.g., цало instead of цѣлo ("whole", neutr. sing.), цаловати instead of цѣлoвати ("to kiss"), цаломѫдрьно instead of цѣломѫдрьно ("chastely"), рѫца instead of рѫцѣ ("hands", dual), etc. etc.[23][20]

An opposite process of narrowing of yat into /ɛ/ started in the west in the 1200s, with a first example of consistent replacement of ⟨ѣ⟩ with ⟨є⟩ in Tsar Constantine Tikh's Virgin Charter of the early 1260s.[24] The Charter, which was written in Skopje, predates the first Ekavian Serbian document (dated to 1289) by 15–20 years, which refutes the nationalistic claims of Serbian linguists, e.g. Aleksandar Belić that Ekavism is a uniquely Serbian phenomenon and confirms, e.g., nl:Nicolaas van Wijk's theory that it is a native Western Bulgarian development.[25]

Mirchev and Totomanova have linked the mutation of yat into /ɛ/ to either consonant depalatalization in stressed syllables or to unstressed syllables.[26] Thus, those Bulgarian dialects that retained their palatalized consonants remained Yakavian in stressed syllables, whereas those that lost them moved towards Ekavism; unstressed yat, in turn, became /ɛ/ practically everywhere.[27] This eventually led to the current dialectal division of Eastern South Slavic into Eastern Bulgarian Yakavian and Western Bulgarian and Macedonian Ekavian.

The different reflexes of yat define the so-called yat boundary (ятова граница), which currently runs roughly from Nikopol on the Danube to Thessaloniki on the Aegean Sea. West of that isogloss, yat is always realized as /ɛ/. East of it, there are different types of yakavism. Standard Bulgarian's alternation of yat between /ja/ or /ʲa/ in stressed syllable before a hard syllable/consonant and /ɛ/ in all other cases is only characteristic of the Balkan dialects (cf. Maps no. 1 & 2).

Examples of the alternation in the standard language (and the Balkan dialects) in the form (stressed, followed by hard consonant/syllable)→(stressed, followed by soft consonant/syllable)→(unstressed) follow below:

- бял [ˈbʲal] ("white", masc. sing.) [adj.] → бели [ˈbɛli] ("white", pl.) [adj.] → белота [bɛloˈta] ("whiteness") [n.]

- мляко [ˈmlʲako] ("milk") [n.] → млечен [ˈmlɛt͡ʃɛn] ("milky") [adj.] → млекар [mlɛˈkar] ("milkman") [n.]

- пяна [ˈpʲanɐ] ("foam") [n.] → пеня се [ˈpɛnʲɐ sɛ] ("to foam") [v.] → пенлив [pɛnˈliv] ("foamy") [adj.]

- смях [ˈsmʲah] ("laughter") [n.] → смея се [ˈsmɛjɐ sɛ] ("to laugh") [v.] → смехотворен [smɛhoˈtvɔrɛn] ("laughable") [adj.]

- успях [osˈpʲah] ("(I) succeeded") [v.] → успешен [osˈpɛʃɛn] ("successful") [adj.] → успеваемост [ospɛˈvaɛmost] ("success rate") [n.]

- бряг [ˈbrʲak] ("coast") [n.] → крайбрежен [krɐjˈbrɛʒɛn] ("coastal") [adj.] → брегът [brɛˈgɤt] ("the coast") [n.]

The Moesian dialects in the northeast and the Rup dialects in the southeast feature a variety of other alternations, most commonly /ja/ or /ʲa/ in stressed syllable before hard consonant/syllable, /æ/ in stressed syllable before soft consonant/syllable and /ɛ/ in unstressed syllables (cf. Maps no. 1 & 2). The open articulation as /æ/ before hard consonant/syllable has survived only in isolated dialects, e.g., Banat Bulgarian and in clusters along the yat boundary. The open articulation as ⟨а⟩ after hardened ⟨ц⟩ (/t͡s/) survives as a remnant of former yakavism in a number of western Bulgarian and eastern Macedonian dialects (cf. Map no. 3).[28]

As the yat boundary is only one of many isoglosses that divides the dialects of Eastern South Slavic into Western and Eastern,[29] the term "Yat Isogloss Belt" has recently superseded the term "yat boundary". The Belt unifies Yakavian and Ekavian dialects with mixed, Western and Eastern traits into a buffer zone that ensures a gradual transition between the two major dialect groups.

From the late 19th century until 1945, standard Bulgarian orthography did not reflect the /ja/ and /ɛ/ alternation and used the Cyrillic letter ⟨ѣ⟩ for both in yat's etymological place. This was regarded as a way to maintain unity between Eastern and Western Bulgarians, as much of what was then seen as Western Bulgarian dialects was under foreign control. However, this also complicated orthography for a country that was generally Eastern-speaking. There were several attempts to restrict the use of the letter only to those word forms where there was a difference in pronunciation between Eastern and Western Bulgarian (e.g., in the failed orthographic reform of 1892 and in several proposals by professor Stefan Mladenov in the 1920s and 1930s), but the use of the letter remained largely etymological. In response, in the Interwar period, the Bulgarian Communist Party started referring to the letter as a manifestation of "class elitism" and "Greater Bulgarian Chauvinism" and made its elimination a top priority.

Consequently, after Bulgaria's occupation by the Soviet Union in 1944 and the installation of a puppet government headed by the communists, ⟨ѣ⟩ was summarily thrown of the Bulgarian alphabet and the spelling changed to conform to the Eastern pronunciation by an orthographic reform in 1945 despite any objections.[30] After 1989, the elimination of yat from the alphabet has generally been regarded as a violation of the unity of the Bulgarian language,[31] in particular, in right-leaning circles, and nationalistic parties like VMRO-BND have campaigned, unsuccessfully, for its reintroduction.

Notably, the Macedonian Patriotic Organization, an organisation of Macedonian Bulgarian emigrants in North America, continued to use ⟨ѣ⟩ in the Bulgarian edition of newsletter, Macedonian Tribune, until it switched to an English-only version in the early 1990s.[32][33]

Russian

editIn Russian, written confusion between the yat and ⟨е⟩ appears in the earliest records; when exactly the distinction finally disappeared in speech is a topic of debate. Some scholars, for example W. K. Matthews, have placed the merger of the two sounds at the earliest historical phases (the 11th century or earlier), attributing its use until 1918 to Church Slavonic influence. Within Russia itself, however, a consensus has found its way into university textbooks of historical grammar (e.g., V. V. Ivanov), that, taking all the dialects into account, the sounds remained predominantly distinct until the 18th century, at least under stress, and are distinct to this day in some localities. Meanwhile, the yat in Ukrainian usually merged in sound with /i/ instead (see below).

The story of the letter yat and its elimination from the Russian alphabet makes for an interesting footnote in Russian cultural history. See Reforms of Russian orthography for details. A full list of words that were written with the letter yat at the beginning of 20th century can be found in the Russian Wikipedia.

A few inflections and common words were distinguished in spelling by ⟨е⟩ / ⟨ѣ⟩ (for example: ѣ́сть / е́сть [ˈjesʲtʲ] "to eat" / "(there) is"; лѣчу́ / лечу́ [lʲɪˈt͡ɕu] "I heal" / "I fly"; синѣ́е / си́нее [sʲɪˈnʲe.jɪ], [ˈsʲi.nʲɪ.jɪ] "bluer" / "blue" (n.); вѣ́дѣніе / веде́ніе [ˈvʲe.dʲɪ.nʲjə], [vʲɪˈdʲe.nʲjə] "knowledge" / "leadership").

The retention of the letter without discussion in the Petrine reform of the Russian alphabet of 1708 indicates that it then still marked a distinct sound in the Moscow koiné of the time. However, in 1748 an early proposal for partial revision of the usage of ⟨ѣ⟩ was made by Vasily Trediakovsky.[34] The polymath Lomonosov in his 1755 grammar noted that the sound of ⟨ѣ⟩ was scarcely distinguishable from that of the letter ⟨е⟩,[35] although he firmly defended their distinction in spelling.[36] A century later (1878) the philologist Grot stated flatly in his standard Russian orthography (Русское правописаніе, Russkoje pravopisanije) that in the common language there was no difference whatsoever between their pronunciations. However, dialectal studies in the 20th century have shown that, in certain regional dialects, a phonemically distinct reflex of *ě has still been retained.[37]

Some reflexes of ⟨ѣ⟩ have further evolved into /jo/, especially in inflected forms of words where ⟨ѣ⟩ have become stressed, while the dictionary form has it unstressed. One such example is звѣзда [zvʲɪzˈda] "star" against звѣзды [ˈzvʲɵzdɨ] "stars". Some dictionaries used a yat with a diaeresis, ⟨ѣ̈⟩, to denote this sound, in a similar fashion to the creation of the letter ⟨ё⟩.

A proposal for spelling reform from the Russian Academy of Science in 1911 included, among other matters, the systematic elimination of the yat, but was declined at the highest level.[citation needed] According to Lev Uspensky's popular linguistics book A Word on Words (Слово о словах), yat was "the monster-letter, the scarecrow-letter ... which was washed with the tears of countless generations of Russian schoolchildren".[38] The schoolchildren made use of mnemonic nonsense verses made up of words with ⟨ѣ⟩:

| Бѣдный блѣдный бѣлый бѣсъ | [ˈbʲɛ.dnɨj ˈblʲɛ.dnɨj ˈbʲɛ.lɨj ˈbʲɛs] | The poor pale white demon |

| Убѣжалъ съ обѣдомъ въ лѣсъ | [u.bʲɪˈʐal sɐˈbʲɛ.dəm ˈvlʲɛs] | Ran off with lunch into the forest |

| ... | ... | ... |

The spelling reform was promulgated by the Provisional Government in the summer of 1917. However, it was not implemented under the prevailing conditions. After the Bolshevik Revolution, the new regime took up the Provisional Drafts, implementing them minor deviations.[39][40] Orthography came to be viewed by many as an issue of politics, and the letter yat its primary symbol. Émigré Russians generally adhered to the old spelling until after World War II; long and impassioned essays were written in its defense, as by Ivan Ilyin in 1952 (О русскомъ правописаніи, O russkom pravopisanii). Even in the Soviet Union, it is said that some printing shops continued to use the eliminated letters until their blocks of type were forcibly removed; the Academy of Sciences published its annals in the old orthography until approximately 1924.[citation needed] The older spelling practice within Russia was ended thourgh government pressure as well as by the large-scale campaign for literacy in 1920s and 1930s, conducted in accordance with the new norm.[41]

According to the reform, yat was replaced by ⟨е⟩ in most words, e.g. дѣти, совѣтъ became дети, совет; for a small number of words it was replaced by ⟨и⟩ instead, according to pronunciation: онѣ ('those', feminine), однѣ ('one', feminine plural), однѣхъ, однѣмъ, однѣми (declined forms of однѣ were replaced with они, одни, одних, одним, одними.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, as a tendency occasionally to mimic the past appeared in Russia, the old spelling became fashionable in some brand names and the like, as archaisms, specifically as "sensational spellings". For example, the name of the business newspaper Kommersant appears on its masthead with a word-final hard sign, which is superfluous in modern orthography: "Коммерсантъ". Calls for the reintroduction of the old spelling were heard, though not taken seriously, as supporters of the yat described it as "that most Russian of letters", and the "white swan" (бѣлый лебедь) of Russian spelling.[citation needed]

Ukrainian

editIn Ukrainian, yat has traditionally represented /i/ or /ji/. In modern Ukrainian orthography its reflexes are represented by ⟨і⟩ or ⟨ї⟩. As Ukrainian philologist Volodymyr Hlushchenko notes that initially in proto-Ukrainian tongues yat used to represent /ʲe/ or /je/ which around 13th century transitioned into /i/.[42] Yet, in some phonetic Ukrainian orthographies from the 19th century, it was used to represent both /ʲe/ or /je/ as well as /i/. This corresponds more with the Russian pronunciation of yat rather than actual word etymologies. Return to /ʲe/ or /je/ pronunciation was initiated by the Pavlovsky "Grammar of the Little Russian dialect" (1818) according to Hryhoriy Pivtorak.[43] While in the same "Grammar" Pavlovsky states that among Little Russians "yat" is pronounced as /i/ (Ѣ произносится какъ Россїйское мягкое j. на пр: ні́жный, лі́то, слідъ, тінь, сі́но.).[44] The modern Ukrainian letter ⟨є⟩ has the same phonetic function. Several Ukrainian orthographies with the different ways of using yat and without yat co-existed in the same time during the 19th century, and most of them were discarded before the 20th century. After the middle of the 19th century, orthographies without yat dominated in the Eastern part of Ukraine, and after the end of the 19th century they dominated in Galicia. However, in 1876–1905 the only Russian officially legalized orthography in the Eastern Ukraine was based on Russian phonetic system (with yat for /je/) and in the Western Ukraine (mostly in Carpathian Ruthenia) orthography with yat for /i/ was used before 1945; in the rest of the western Ukraine (not subjected to the limitations made by the Russian Empire) the so-called "orthographic wars" ended up in receiving a uniformed phonetic system which replaced yat with either ⟨ї⟩ or ⟨і⟩ (it was used officially for Ukrainian language in the Austrian Empire).

'New yat' is a reflex of /e/ (which merged with yat in Ukrainian) in closed syllables. New yat is not related to the Proto-Slavic yat, but it has frequently been represented by the same sign. Using yat instead of ⟨е⟩ in this position was a common after the 12th century. With the later phonological evolution of Ukrainian, both yat and new yat evolved into /i/ or /ji/. Some other sounds also evolved to the sound /i/ so that some Ukrainian texts from between the 17th and 19th centuries used the same letter (⟨и⟩ or yat) uniformly rather than variation between yat, new yat, ⟨и⟩, and reflex of ⟨о⟩ in closed syllables, but using yat to unify all i-sounded vowels was less common, and so 'new yat' usually means letter yat in the place of i-sounded ⟨е⟩ only. In some etymology-based orthography systems of the 19th century, yat was represented by ⟨ѣ⟩ and new yat was replaced with ⟨ê⟩ (⟨e⟩ with circumflex). At this same time, the Ukrainian writing system replaced yat and new yat by ⟨і⟩ or ⟨ї⟩.

Rusyn

editIn Rusyn, yat was used until 1945. In modern times, some Rusyn writers and poets try to reinstate it, but this initiative is not really popular among Rusyn intelligentsia.[45]

Romanian

editIn the old Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, the yat, called eati, was used as the /e̯a/ diphthong. It disappeared when Romanian adopted the transitional alphabet, first in Wallachia, then in Moldavia.

Serbo-Croatian

editThe Old Serbo-Croatian yat phoneme is assumed to have a phonetic value articulatory between the vowels /i/ and /e/. In the Štokavian and Čakavian vowel systems, this phoneme lost a back vowel parallel; the tendency towards articulatory symmetry led to its merging with other phonemes.[citation needed]

On the other hand, most Kajkavian dialects did have a back vowel parallel (a reflex of *ǫ and *l̥), and both the front and back vowels were retained in most of these dialects' vowel system before merging with a reflex of a vocalized Yer (*ь). Thus the Kajkavian vowel system has a symmetry between front and back closed vocalic phonemes: */ẹ/ (< */ě/, */ь/) and */ọ/ (< */ǫ/, */l̥/).

Čakavian dialects utilized both possibilities of establishing symmetry of vowels by developing Ikavian and Ekavian reflexes, as well as "guarding the old yat" at northern borders (Buzet dialect). According to yat reflex Čakavian dialects are divided to Ikavian (mostly South Čakavian), Ekavian (North Čakavian) and mixed Ikavian-Ekavian (Middle Čakavian), in which mixed Ikavian-Ekavian reflex is conditioned by following phonemes according to Jakubinskij's law (e.g. sled : sliditi < PSl. *slědъ : *slěditi; del : diliti < *dělъ : *děliti). Mixed Ikavian-Ekavian Čakavian dialects have been heavily influenced by analogy (influence of nominative form on oblique cases, infinitive on other verbal forms, word stem onto derivations etc.). The only exception among Čakavian dialects is Lastovo island and the village of Janjina, with Jekavian reflex of yat.

The most complex development of yat has occurred in Štokavian, namely Ijekavian Štokavian dialects which are used as a dialectal basis for modern standard Serbo-Croatian variants, and that makes the reflexes of yat one of the central issues of Serbo-Croatian orthoepy and orthography. In most Croatian Štokavian dialects yat has yielded diphthongal sequence of /ie̯/ in long and short syllables. The position of this diphthong is equally unstable as that of closed */ẹ/, which has led to its dephonologization. Short diphthong has thus turned to diphonemic sequence /je/, and long to disyllabic (triphonemic) /ije/, but that outcome is not the only one in Štokavian dialects, so the pronunciation of long yat in Neo-Štokavian dialects can be both monosyllabic (diphthongal or triphthongal) and disyllabic (triphonemic). However, that process has been completed in dialects which serve as a dialectal basis for the orthographical codification of Ijekavian Serbo-Croatian. In writing, the diphthong /ie̯/ is represented by the trigraph ⟨ije⟩ – this particular inconsistency being a remnant of the late 19th century codification efforts, which planned to redesign common standard language for Croats and Serbs. This culminated in the Novi Sad agreement and "common" orthography and dictionary. Digraphic spelling of a diphthong as e.g. was used by some 19th-century Croat writers who promoted so-called "etymological orthography" – in fact morpho-phonemic orthography which was advocated by some Croatian philological schools of the time (Zagreb philological school), and which was even official during the brief period of the fascist Independent State of Croatia (1941–1945). In standard Croatian, although standard orthography is ⟨ije⟩ for long yat, standard pronunciation is /jeː/. Serbian has two standards: Ijekavian is /ije/ for long yat and Ekavian which uses /e/ for short and /eː/ for long yat.

Standard Bosnian and Montenegrin use /je/ for short and /ije/ for long yat.

Dephonologization of diphthongal yat reflex could also be caused by assimilation within diphthong /ie̯/ itself: if the first part of a diphthong assimilates secondary part, so-called secondary Ikavian reflex develops; and if the second part of a diphthong assimilates the first part secondary Ekavian reflex develops. Most Štokavian Ikavian dialects of Serbo-Croatian are exactly such – secondary Ikavian dialects, and from Ekavian dialects secondary are the Štokavian Ekavian dialects of Slavonian Podravina and most of Serbia. They have a common origin with Ijekavian Štokavian dialects in a sense of developing yat reflex as diphthongal reflex. Some dialects also "guard" older yat sound, and some reflexes are probably direct from yat.

Direct Ikavian, Ekavian and mixed reflexes of yat in Čakavian dialects are a much older phenomenon, which has some traces in written monuments and is estimated to have been completed in the 13th century. The practice of using old yat phoneme in Glagolitic and Bosnian Cyrillic writings in which Serbo-Croatian was written in the centuries that followed was a consequence of conservative scribe tradition. Croatian linguists also speak of two Štokavians, Western Štokavian (also called Šćakavian) which retained yat longer, and Eastern Štokavian which "lost" yat sooner, probably under (western) Bulgarian influences. Areas which bordered Kajkavian dialects mostly retained yat, areas which bordered Čakavian dialects mostly had secondary Ikavisation, and areas which bordered (western) Bulgarian dialects mostly had secondary Ekavisation. "Core" areas remained Ijekavian, although western part of the "core" became monosyllabic for old long yat.

Reflexes of yat in Ijekavian dialects are from the very start dependent on syllable quantity. As it has already been said, standard Ijekavian Serbo-Croatian writes trigraph ⟨ije⟩ at the place of old long yat, which is in standard pronunciation manifested disyllabically (within Croatian standard monosyllabic pronunciation), and writes ⟨je⟩ at the place of short yat. E.g. bijȇl < PSl. *bělъ, mlijéko < *mlěko < by liquid metathesis from *melkò, brijȇg < *brěgъ < by liquid metathesis from *bȇrgъ, but mjȅsto < *mě̀sto, vjȅra < *vě̀ra, mjȅra < *mě̀ra. There are however some limitations; in front of /j/ and /o/ (< word-final /l/) yat has a reflex of short /i/. In scenarios when /l/ is not substituted by /o/, i.e. not word-finally (which is a common Štokavian isogloss), yat reflex is also different. E.g. grijati < *grějati, sijati < *sějati, bijaše < *bějaše; but htio : htjela < *htělъ : *htěla, letio : letjela (< *letělъ : *letěla). The standard language also allows some doublets to coexist, e.g. cȉo and cijȇl < *cě̑lъ, bȉo and bijȇl < *bě́lъ.

Short yat has reflexes of /e/ and /je/ behind /r/ in consonant clusters, e.g. brȅgovi and brjȅgovi, grehòta and grjehòta, strèlica and strjèlica, etc.

If short syllable with yat in the word stem lengthens due to the phonetic or morphological conditions, reflex of /je/ is preserved, e.g. djȅlo – djȇlā, nèdjelja – nȅdjēljā.

In modern standard Ijekavian Serbo-Croatian varieties syllables that carry yat reflexes are recognized by alternations in various inflected forms of the same word or in different words derived from the same stem. These alternating sequences ⟨ije/je, ije/e, ije/i, ije/Ø, ije/i, je/ije, e/ije, e/je, i/ije⟩ are dependent on syllable quantity. Beside modern reflexes they also encompass apophonic alternations inherited from Proto-Slavic and Indo-European times, which were also conditioned by quantitative alternations of root syllable, e.g. ùmrijēti – ȕmrēm, lȉti – lijévati etc. These alternations also show the difference between the diphthongal syllables with Ijekavian reflex of yat and syllables with primary phonemic sequence of ⟨ije⟩, which has nothing to do with yat and which never shows alternation in inflected forms, e.g. zmìje, nijèdan, òrijent, etc.

Computing codes

edit| Preview | Ѣ | ѣ | ᲇ | Ꙓ | ꙓ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER YAT | CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER YAT | CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TALL YAT | CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER IOTIFIED YAT | CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IOTIFIED YAT | |||||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 1122 | U+0462 | 1123 | U+0463 | 7303 | U+1C87 | 42578 | U+A652 | 42579 | U+A653 |

| UTF-8 | 209 162 | D1 A2 | 209 163 | D1 A3 | 225 178 135 | E1 B2 87 | 234 153 146 | EA 99 92 | 234 153 147 | EA 99 93 |

| Numeric character reference | Ѣ |

Ѣ |

ѣ |

ѣ |

ᲇ |

ᲇ |

Ꙓ |

Ꙓ |

ꙓ |

ꙓ |

See also

edit- Ѧ ѧ : Yus

- Ҍ ҍ : Cyrillic letter Semisoft sign

- Ә ә : Cyrillic schwa, used in Turkic languages and Kalmyk to transcribe the near-open front unrounded vowel (/æ/)

- Ӓ ӓ : Cyrillic letter A with diaeresis, used in Mari to transcribe the near-open front unrounded vowel (/æ/)

- Ě ě : Latin letter E with caron - a Czech and Sorbian letter

References

edit- ^ Mirchev (1978), p. 118.

- ^ a b Mirchev (1978), p. 119.

- ^ Stoykov (1993), pp. 123, 127, 130, 135, 142.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2001), pp. 102, 105, 107, 109.

- ^ Mirchev (1978), p. 119-120.

- ^ Mii, Mii (Dec 6, 2019). "The Russian Spelling Reform of 1917/18 - Part II (Alphabet I)". YouTube.

- ^ Mirchev, Kiril (2000). Старобългарски език [The Old Bulgarian Language] (II ed.). Sofia: Faber. p. 13. ISBN 9549541584.

- ^ a b "Единството на българския език в миналото и днес" [The Unity of the Bulgarian Language in the Present and the Past]. Български език [Bulgarian language] (in Bulgarian). I. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: 16–18. 1978.

- ^ Stoykov (1993), pp. 180.

- ^ Георгиева, Елена и Невена Тодорова, Българските народни говори, София 1986, с. 79. (Georgieva, Elena and Nevena Todorova, Bulgarian dialects, Sofia 1986, p. 79.)

- ^ Бояджиев, Тодор А. Помагало по българска диалектология, София 1984, с. 62. (Boyadzhiev Todor A. "Handbook on Bulgarian Dialectology", Sofia, 1984, р. 62.)

- ^ Trubetzkoy, Nikolai. Principles_of_Phonology, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1977, p. 277, 279 (note 9))

- ^ a b c d Duridanov 1991, pp. 66.

- ^ Mirchev 1978, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Ivanov, Yordan (1931). Български старини из Македония [Bulgarian Historical Monuments in Macedonia] (in Bulgarian) (2nd Extended ed.). Sofia: Държавна печатница. pp. 550 and ff.

- ^ Ivanov, Yordan (1931). Български старини из Македония [Bulgarian Historical Monuments in Macedonia] (in Bulgarian) (2nd Extended ed.). Sofia: Държавна печатница. p. 77.

- ^ Gianelli, Ciro; Vaillant, Andre (1958). Un lexique Macedonien du XVIe siècle [A Macedonian Lexicon from the 16th Century] (in French). Paris: Institut d'Études slaves de l'Université de Paris. pp. 30, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43.

- ^ Nichev, Aleksandar (1987). Костурският българо-гръцки речник от XVI век [The 16th-Century Bulgaro-Greek Dictionary from Kastoria] (in Bulgarian). Sofia: St. Clement of Ohrid University Printing House.

- ^ Duridanov 1991, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Mirchev (1978), pp. 120.

- ^ Totomanova (2014), pp. 75.

- ^ Mirchev (1978), p. 121.

- ^ Totomanova (2014), pp. 76.

- ^ Mirchev (1978), p. 20.

- ^ van Wijk, Nicolaas (1956). Les langues slaves : de l'unité à la pluralité [Slavic Languages: From Unity to Plurality] (in French) (II ed.). Mouton & Co., 's-Gravenhage. p. 110.

- ^ Totomanova (2014), pp. 80–82.

- ^ Totomanova (2014), pp. 82.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2001), p. 95.

- ^ Anna Lazarova, Vasil Rainov, On the minority languages in Bulgaria in Duisburg Papers on Research in Language and Culture Series, National, Regional and Minority Languages in Europe. Contributions to the Annual Conference 2009 of EFNIL in Dublin, issue 81, editor Gerhard Stickel, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3631603657, pp. 97-106.

- ^ Младенов, Стефан. Български етимологичен речник.

- ^ Stoyanov, Rumen (2017). Езиковедски посегателства [Linguistic Violations]. Bulgaria-Macedonia (2). ISSN 1312-0875.

- ^ Pelisterski, Hristo (February 17, 1927). "Our Oath". Macedonian Tribune. 1 (9): 1.

- ^ "Иванъ Михайловъ, легендарният вождъ на Македонското освободително движение, почина" [Ivan Mihailoff, Legendary Leader of the Macedonian Liberation Movement, Is Dead]. Macedonian Tribune. 64 (3078): 3. September 20, 1990. ISSN 0024-9009.

- ^ Каверина, Валерия Витальевна (2021). "Употребление буквы Ѣ в периодических изданиях XVIII–XIX вв.: узус и кодификация". Медиалингвистика. 8 (4): 336–350.

- ^ Ломоносовъ, Михайло (1755). Россійская грамматика. Санктпетербургъ: Императорская Академія Наукъ. p. 49.

буквы Е и Ѣ въ просторѣчіи едва имѣютъ чувствительную разность

- ^ Ломоносовъ 1755:53-54

- ^ Аванесов, Рубен Иванович (1949). Очерки русской диалектологии. Часть первая. Москва: Государственное учебно-педагогическое издательство Министерства просвещения РСФСР. pp. 41–47.

- ^ Успенский, Лев: Слово о словах. Лениздат 1962. p. 148.

- ^ "Декрет о введении нового правописания (Decree on introduction of new orthography)". Известия В.Ц.И.К. 13 October 1918, #223 (487) (in Russian). 1917. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard; Stone, Gerald; Polinsky, Maria (1996). The Russian Language in the Twentieth Century (2nd ed.). Wotton-under-Edge, England: Clarendon Press. p. 290-291. ISBN 978-0198240662.

- ^ Грамматический террор: Как большевики свергли правила орфографии

- ^ Hlushchenko, V. Yat (ЯТЬ). Izbornyk.

- ^ Pivtorak, H. Orthography (ПРАВОПИС). Izbornyk.

- ^ Alexey Pavlovsky Grammar of the Little Russian dialect (ГРАММАТИКА МАЛОРОССІЙСКАГО НАРЂЧІЯ,). Izbornyk.

- ^ "Rusyn Romanization Table, 2013 version" (PDF). Library of Congress. 2013.

Sources

edit- Български диалектален атлас [Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects] (in Bulgarian). Vol. I-III Phonetics. Accentology. Lexicology. София: Trud Publishing House. 2001. ISBN 954-90344-1-0.

- Stoykov, Stoyko (1993). Българска диалектология [Bulgarian Dialectology] (in Bulgarian) (III ed.). Prof. Marin Drinov.

- Duridanov, Ivan (1991). Граматика на старобългарския език [Grammar of Old Bulgarian] (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Bulgarian Language Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 954-430-159-3.

- Mirchev, Kiril (1978). Историческа граматика на българския език [Historical Grammar of the Bulgarian Language] (in Bulgarian) (III ed.). Sofia: Наука и изкуство.

- Totomanova, Anna-Maria (2014). Из българската историческа фонетика [On Bulgarian Historical Phonetics] (in Bulgarian). Sofia: St. Clement of Ohrid University Publisher. ISBN 9789540737881.

Further reading

edit- Barić, Eugenija; Mijo Lončarić; Dragica Malić; Slavko Pavešić; Mirko Peti; Vesna Zečević; Marija Znika (1997). Hrvatska gramatika. Školska knjiga. ISBN 953-0-40010-1.