Women in Kyrgyzstan traditionally had assigned roles, although only the religious elite sequestered women as was done in other Muslim societies.[4] Rural inhabitants continue the traditional Siberian tribal practice of bride kidnapping (abducting women and girls for forced marriage). Bride kidnapping, known as ala kachuu (to take and flee), girls as young as 12 years old are kidnapped for forced marriage, by being captured and carried away by groups of men or even relatives who, through violence or deception, take the girl to the abductor's family who forces and coerces the young woman to accept the illegal marriage. In most cases, the young woman is raped immediately in the name of marriage.

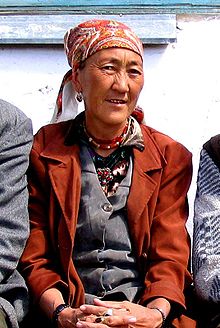

Kyrgyz woman | |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 60(2017) |

| Women in parliament | 16,5% (2020) |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 81.0% (2010) |

| Women in labour force | 57% (2022) [1] |

| Gender Inequality Index[2] | |

| Value | 0.370 (2021) |

| Rank | 87th out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[3] | |

| Value | 0.700 (2022) |

| Rank | 86th out of 146 |

Although the practice is illegal in Kyrgyzstan, bride kidnappers are rarely prosecuted. This reluctance to enforce the code is in part caused by the corrupt legal system in Kyrgyzstan where many villages are de facto ruled by councils of elders and aqsaqal courts following customary law, away from the eyes of the state legal system.

Cultural background

editKyrgyzstan is a country in Central Asia, with strong nomadic traditions. Most of Kyrgyzstan was annexed to Russia in 1876, but the Kyrgyz staged a major Marxism influenced violent conflict with the Tsarist Empire in 1916. Kyrgyzstan became a Soviet republic in 1936, and became an independent state in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed. The current population of the country consists of a Kyrgyz majority (70.9%), followed by Uzbeks at 14.3%, and Russians at 7.7%. There are also other minorities such as Dungan, Uyghur, Tajik, Turk, Kazakh, Tatar, Ukrainian, Korean and German. Most of the population is Muslim (75%), but there is also a significant Russian Orthodox minority (20%). The country is largely rural: only 35.7% of the population lives in urban areas. The total fertility rate is 2.66 children born/woman (2015 estimate), despite the fact that the modern contraceptive prevalence rate is quite low, at 36.3% (2012 estimate). The literacy rate of women is very high at 99.4% (2015 estimate).[5]

Modern times

editIn modern times, especially in the first years of independence, women have played more prominent roles in Kyrgyzstan than elsewhere in Central Asia.[4] As a result of the December 16, 2007 parliamentary elections, 23 women representing three political parties have positions in parliament.[6] As of 2007, women held several high‑level government posts, including minister of finance, minister of education and science, minister of labor and social development, chief justice of the Constitutional Court, the chair of the State Committee on Migration and Employment Issues, and chair of the CEC.[6] As of 2007, no women occupied the positions of governor or head of local government.[6] In August 2007, President Kurmanbek Bakiyev signed into effect an action plan on achieving gender balance for 2007–2010.[6] Between 2007 and 2010, women members of parliament introduced 148 out of the 554 bills that were considered on the floor, covering issues from breastfeeding protection in health bill to the adoption of a law guaranteeing equal rights and opportunities for women and men.[7] In March 2010, opposition politician Roza Otunbaeva rose to power as caretaker president following a revolution against Bakiyev's government, becoming Kyrgyzstan's first female president.[8]

Violence against women

editDespite laws against them, many crimes against women are not reported due to psychological pressure, cultural traditions, and apathy of law enforcement officials. Rape, including spousal rape, is illegal, but enforcement of the law is very poor.[9] Rape is underreported, and prosecutors rarely bring rape cases to court.[9]

Bride kidnapping, forced and early marriage

editAlthough prohibited by law, rural inhabitants continue the traditional practice of bride kidnapping (abducting women and girls for forced marriage). In many primarily rural areas, bride kidnapping, known as ala kachuu (to take and flee), is an accepted and common way of taking a wife. Girls as young as 12 years old are kidnapped for forced marriage, by being captured and carried away by groups of men who, through violence or deception, take the girl to the home of the intended groom, where the abductor's family pressures and coerces the young woman to accept the marriage. In some cases, the young woman is raped in order to force the marriage.[10]

Although the practice is illegal in Kyrgyzstan, bride kidnappers are rarely prosecuted. This reluctance to enforce the code is in part caused by the pluralistic legal system in Kyrgyzstan where many villages are de facto ruled by councils of elders and aqsaqal courts following customary law, away from the eyes of the state legal system.[11] The law against bride kidnapping was toughened in 2013.[12]

Domestic violence

editThe Law on Social and Legal Protection against Domestic Violence (2003)[13] is Kyrgyzstan's law against domestic violence. In practice, police often refuse to register domestic violence complaints, which are seen as private.[14]

Sex trafficking

editCitizen and foreign women and girls are victims of sex trafficking in Kyrgyzstan. They are raped and physically and physiologically harmed in brothels, hotels, homes, and other locations throughout the country.[15][16][17][18][19]

Sexual harassment

editSexual harassment is prohibited by law;[20] however, according to an expert at the local NGO Shans, it is rarely reported or prosecuted.[6]

Violent extremism and terrorism

editISIS recruitment occurs on a small scale in Kyrgyzstan. From 2010-2016 the government reported that 863 citizens had participated as foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq, 188 of which were women.[21] It has been suggested that women in Kyrgyzstan join due to either family pressure from the husband or sometimes other relatives, which has been referred to as "zombification," or as a way to seek higher social status, financial prosperity, and sometimes the offer of marriage.[22]

Women in law enforcement and security

editThe Association of Women Police of Kyrgyzstan was established in 2010 with the aim of supporting female police officers and to advocate for gender equality in law enforcement and within government more generally. In March 2017 the Association of Women in the Security Sector was established in Bishkek. Both entities are supported by the OSCE in Kyrgyzstan.[23] [24]

Legal rights and gender equality

editWomen enjoy the same rights as men, including under family law, property law, and in the judicial system, although discrimination against women persists in practice.[6] The 2010 Constitution of Kyrgyzstan insures gender equality. Article 16 reads: (2) [...] "No one may be subject to discrimination on the basis of sex, race, language, disability, ethnicity, belief, age, political and other convictions, education, background, proprietary and other status as well as other circumstances." (4)"In the Kyrgyz Republic men and women shall have equal rights and freedoms and equal opportunities for their realization."[25] The Soviet rulers claimed to have abolished many harmful traditions deriving from discriminatory nomadic practices and customs, such as bride price and forced marriage, although it is debatable to what extent this was true - according to some sources "Traditional marriage practices in the rural regions [...] have been little affected by Soviet domination", while the bride price, although outlawed by the communist regime, continued under the guise of "gifts".[26] Today, in practice, women, especially in remote rural areas, are often discriminated and prevented from enjoying their legal rights, and are often unaware of their rights and "[t]hey do not know that they can report beatings by their husbands to the police."[27]

On March 26 2007, parliament voted against a measure to decriminalize polygamy.[6] Although no official statistics were available, Minister of Justice Marat Kaiypov stated that the ministry prosecutes two to three polygamy cases each year.[6]

Gallery

edit-

Girl near Tash Rabat, Naryn Province

-

A female student

-

Women and children eating in Suusamyr Valley

-

A woman working on an organic farm

References

edit- ^ https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.ACTI.FE.ZS

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Global Gender Gap Report 2022" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ a b Olcott, Martha Brill. "The Role of Women". Kyrgyzstan country study (Glenn E. Curtis, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (March 1996). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Kyrgyz Republic (2007). United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (March 18, 2008). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Widening women's political representation in Kyrgyzstan", United Nations Development Programme, August 11, 2010.

- ^ "Otunbaeva Inaugurated as Kyrgyz President", Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2016". State.gov. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Reconciled to Violence". Hrw.org. 26 September 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ See Judith Beyer, "Kyrgyz Aksakal Courts: Pluralistic Accounts of History", Journal of Legal Pluralism, 2006; Handrahan, pp. 212–213.

- ^ "New law in Kyrgyzstan toughens penalties for bride kidnapping". Unwomen.org. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Legislationline". Legislationline.org. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch Memorandum : Domestic violence in Kyrgyzstan" (PDF). Hrw.org. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Trafficked: Three survivors of human trafficking share their stories". UN Women. July 29, 2019.

- ^ "Atai Moldobaev: Kyrgyzstan's unconventional problem with human trafficking". CABAR. January 31, 2017.

- ^ "Kyrgyz Victims Recount Horrors Of Sex Trafficking". Radio Free Europe. October 14, 2014.

- ^ "Report: Mother Threatened After Coverage Of Kyrgyz Sex-Trafficking Case". Current Time. January 28, 2020.

- ^ "One in five girls and women kidnapped for marriage in Kyrgyzstan: study". Reuters. August 1, 2017.

- ^ [1] Archived 2015-12-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Women and Violent Extremism in Europe and Central Asia: The Roles of Women in Supporting, Joining, Intervening in, and Preventing Violent Extremism inKyrgyzstan. UN Women. June 2017.

- ^ Women and Violent Extremism in Europe and Central Asia: The Roles of Women in Supporting, Joining, Intervening in, and Preventing Violent Extremism inKyrgyzstan. UN Women. June 2017.

- ^ "OSCE supports establishment of Kyrgyz Association of Women in the Security Sector". OSCE.

- ^ "Police women in Kyrgyzstan: Challenges and Prospects". UNODC.

- ^ "THE CONSTITUTION OF THE KYRGYZ REPUBLIC, 2010" (PDF). Users.unimi.it. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Kyrgyz facts, information, pictures - Encyclopedia.com articles about Kyrgyz". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Tradition and lack of awareness fuel domestic violence". Irinnews.org. 7 March 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2017.