Winter Park is a city in Orange County, Florida, United States. The population was 29,795 according to the 2020 census. It is part of the Orlando–Kissimmee–Sanford, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Winter Park, Florida | |

|---|---|

| City of Winter Park | |

| Motto(s): "City of Culture and Heritage" | |

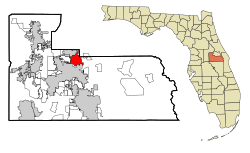

Location in Orange County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 28°35′46″N 81°20′48″W / 28.59611°N 81.34667°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Orange |

| Settled (Lakeview) | 1858[1][2] |

| Settled (Osceola) | 1870[1][2] |

| Incorporated (Town of Winter Park) | October 21, 1887[1][2] |

| Incorporated (City of Winter Park) | 1925[1][2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Commission–Manager |

| • Mayor | Sheila DeCiccio |

| • Commissioners | Marty Sullivan, Craig Russell, Kris Cruzada, and Todd Weaver |

| • City Manager | Randy B. Knight |

| • City Clerk | Rene Cranis |

| • City Attorney | A. Kurt Ardaman |

| Area | |

• Total | 10.38 sq mi (26.89 km2) |

| • Land | 8.76 sq mi (22.70 km2) |

| • Water | 1.62 sq mi (4.19 km2) |

| Elevation | 92 ft (28 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 29,795 |

| • Density | 3,400.09/sq mi (1,312.71/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 32789, 32790 (PO box), 32792, 32793 (PO box) |

| Area code(s) | 407, 689 |

| FIPS code | 12-78300[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0293428[5] |

| Website | cityofwinterpark |

Winter Park was founded as a resort community by northern business magnates in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.^ Its main street, called Park Avenue, is located in the middle of town. It includes civic buildings, retail, art galleries, a private liberal arts college (Rollins College), museums, a park, a train station, a golf course country club, a historic cemetery, and a beach and boat launch.

History

editThe Winter Park area's first human residents were migrant Muscogee people who had earlier intermingled with the Choctaw and other indigenous people. In a process of ethnogenesis, the Native Americans formed a new culture which they called "Seminole", a derivative of the Mvskoke' (a Creek language) word simano-li, an adaptation of the Spanish cimarrón which means "wild" (in their case, "wild men"), or "runaway" [men]. The site was first inhabited by Europeans in 1858, when David Mizell Jr. bought an 8-acre (32,000 m2) homestead between Lakes Virginia, Mizell, and Berry. A settlement, called "Lake View" by the inhabitants, grew up around Mizell's plot. It got a post office and a new name—"Osceola"—in 1870.[1][2]

The area did not develop rapidly until 1880, when a South Florida Railroad track connecting Orlando and Sanford was laid a few miles west of Osceola. Shortly afterwards, Loring Chase came to Orange County from Chicago to recuperate from a lung disease. In his travels, he discovered the pretty group of lakes just east of the railbed. He enlisted a wealthy New Englander, Oliver E. Chapman, and they assembled a very large tract of land for $13,000 on July 4, 1881. They planned the town of Winter Park on this piece of land. Over the next four years they plotted the town, opened streets, built a town hall and a store, planted orange trees, and required all buildings to meet stylistic and architectural standards. Winter Park was a heavily planned city, something that is still evident in its streets’ grid-like organization. The town was then promoted heavily, especially to snow birds in the north looking for a place to hibernate in the winter. During this founding time, the Winter Park Post Office opened, and the railroad constructed a depot, connected to Osceola by a dirt road.

In 1885, a group of businessmen started the Winter Park Company and incorporated it with the Florida Legislature; Chase and Chapman sold the town to the new company. In a land bubble characteristic of Florida history, land prices soared from less than $2 per acre to over $200, with at least one sale recorded at $300 per acre. This land bubble concept would never go away, with towns and counties directly surrounding the area with exponentially cheaper land prices.

In 1885, the Congregational Assembly of Florida started Rollins College, the state's first four-year college. Rollins College today remains one of the hallmarks of Winter Park, an integral part of Winter Park's history and culture.[6] It is the second most expensive college in the state, as of the 2023-2024 academic year the tuition at Rollins is $58,300 per year.[7][8] Rollins is a relatively good liberal arts school, with a smaller student population, counted as roughly just over 2,000 students. The school also features an MBA program, at the Crummer Graduate School of Business.[9] Back in 1886, the Seminole Hotel on Lake Osceola opened. This was a resort complete with the luxuries of the day: gas lights, steam heating, a string orchestra, a formal dining room, a bowling alley, and long covered porches.[citation needed] This street is now a cul de sac called Kiwi Circle that is part of one of the nicest neighborhoods in the town. On October 21, 1887, it was officially incorporated as the "Town of Winter Park", and in 1925, reincorporated as the "City of Winter Park".[1][2]

Presidential visits

editThe first president to visit was Chester A. Arthur, who reported that Winter Park was "the prettiest place I have seen in Florida",. President Grover Cleveland visited the area and was given a huge reception at the Seminole Hotel on February 23, 1888. He enjoyed the Bounding Horse Cart ride and stated that it was the most pleasant diversion of his Florida trip. The New York Times reported on his visit that "The Philadelphian and Bostonian founders had done a good job with the town."

The following four years both hotel and the town became a fashionable winter resort for northern visitors. The next president to visit the area was Franklin D. Roosevelt in March 1936. He was conferred an honorary degree in literature at Rollins College.

President Barack Obama visited Rollins College on August 2, 2012, to give a speech that was part of his re-election campaign. An interesting note on recent Presidential elections is that Orange County, the county Winter Park is in, was one of the bluest counties in Florida. Although Winter Park is a large mix of both conservative and liberal constituents. However, this mix is evident in US Congressional District 7's last two representatives. Former Republican Congressman John Mica lost reelection in 2016 to newcomer and Democrat Stephanie Murphy. Both have had a lot of support from both sides of the aisle and Murphy is credited with being one of the most centrist representatives in Congress today.

Winter Park Public Library

editThe Winter Park Public Library was historically located at 460 E. New England Avenue in the heart of Winter Park. Its origins date back to 1885, when nine women organized to create a lending library for their small community, which was still in its infancy at the time. The Winter Park Public Library underwent major changes and moved to a new site. It opened in late 2021 on a new world-class campus designed by world-renowned architect Sir David Adjaye.

Peacocks

editIn 1904, Charles Hosmer Morse became the biggest landowner in Winter Park. His patronage continued in the 1920s, when he purchased a 200-acre parcel between lakes Virginia, Berry, and Mizell. In 1945, Morse's granddaughter Jeannette and her husband Hugh McKean moved to the land, and soon after they added peacocks. Now, the land is a nature preserve that houses an orange grove and over 30 peacocks. Winter Park locals consider the peacock to be a pet to the entire community. The peacock is on the official Winter Park seal, is featured in a number of official city documents, and is protected by the community. Peacocks often roam around in neighborhoods, especially throughout the community of Windsong, where residents are often seen taking care of them.[10][11]

The Winter Park Sinkhole

editIt has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Winter Park sinkhole. (Discuss) (December 2021) |

In 1972, Henry Swanson, an agricultural agent and "resident layman expert on Central Florida water," wrote a letter to the editor warning Orange County mayors of the sinkhole danger that could be posed by overdevelopment and excessive groundwater use. Swanson predicted that the west Winter Park area would be especially at risk.[12] In May 1981, during a period of record-low water levels in Florida's limestone aquifer, a massive sinkhole opened near the corner of Denning Drive and Fairbanks Avenue.

The sinkhole first appeared on the evening of May 8, 1981, near the house of Winter Park resident Mae Rose Williams.[13][14] Within a few hours, a 40-year-old sycamore tree near her house had fallen into the sinkhole.[13][15] The next morning, the hole expanded to nearly 40 feet (12 m) wide.[15] In a story in the Orlando Sentinel, she said that as the sun rose, she heard a noise "like giant beavers chewing" as the hole began to devour more of her land. The hole was collapsing rapidly.[15] By noon, as she realized that her home was slipping into the expanding hole, she and the family evacuated and removed their belongings. That afternoon her house fell into the sinkhole, and within a few hours the house was irrevocably on its way into the sinkhole's center, headed to unknown depths.

The hole eventually widened to 320 feet (98 m) and to a depth of 90 feet (27 m). The following fell into the sinkhole: five Porsches at a repair shop, a pickup truck with camper top, the Winter Park municipal pool, and large portions of Denning Drive.[16] By May 9, nearly 250,000 cubic yards (190,000 m3) of earth had fallen into the sinkhole. Damage was estimated at $2 million to $4 million.[12] On May 9, 1981, the sinkhole grew to a record size, gulping down 250,000 cubic yards of soil and taking with it the deep end of an Olympic-size swimming pool, chunks of two streets and Williams' three-bedroom home and yard. Florida engineers have described the event as "the largest sinkhole event witnessed by man as a result of natural geological reasons or conditions."[15] They based their statements on his study of 2,000 sinkholes over more than 40 years. That opinion was echoed by Ardaman & Associates, a local engineering consulting firm.

The sinkhole drew national attention and became a popular tourist attraction during the summer of 1981. A carnival-like atmosphere arose around the area, with vendors selling food, balloons, and T-shirts to visitors. The city of Winter Park sold sinkhole photographs for promotional and educational purposes.[12] On July 9, 1981, Winter Park began selling sinkhole photographs to educate the community about sinkholes and to promote tourism. The sinkhole began to fill with water that summer, but on July 19, the water level suddenly dropped by a reported 15 to 20 feet (4.6 to 6.1 m).[12]

As the novelty wore off, the city worked to repair the damage. Workers were able to recover four of the six vehicles that fell into the sinkhole, including the travel trailer, whose owner drove it away, and three of the five Porsches. The other two remain at the bottom of the lake with Mae Rose Owens' home. Engineers filled in the bottom with dirt and concrete.[13] Diver reports from 2009 suggest that the lake has since been used to dispose of unwanted vehicles.[15] Besides a 1987 incident in which the bottom of the lake suddenly dropped 20 feet (6.1 m), causing erosion on the southern rim, the stabilized sinkhole has been generally quiet.[12]

The Langford Resort Hotel

editThe Langford Hotel served as a gateway to "Old Florida" attractions in Central Florida and a community social hub for decades.

Famous guests included Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, Larry King, Hugh Hefner, John Denver, Langford winter resident Lady Bird Johnson, and President Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy Reagan, who celebrated their 24th wedding anniversary there.[17] Reagan gave a campaign speech at Rollins College and stayed at the Langford in 1976.

The Langford was celebrated in a party in late 1999, closed, and was demolished.[18] A portion of the former Langford property (as of mid-2009) has been developed into luxury mid-rise condominiums. The remaining parcel was redeveloped and in 2014, a boutique hotel named the Alfond Inn, owned and operated by Rollins College[19] opened at the site of the original Langford Hotel. The Alfond Inn was built with a $12.5 million grant from the Harold Alfond Foundation. Net operating income from the Inn is directed to The Alfond Scholars program fund, the College's premier scholarship fund.[20]

The Temple Grove

editAn orange grove, known as the Temple Grove, stood on the south side of Palmer Avenue just east of Temple Drive. The temple orange was grown on the old Wyeth grove on Palmer Avenue (later Temple Grove) owned at the time by Louis A. Hakes, whose son was the first to notify Temple of the different quality of the new orange. The orange was introduced and cataloged by Buckeye Nursery in 1917, the year W. C. Temple died. Myron E. Gillett and his son D. Collins Gillett later went on to plant the largest orange grove in the world in the 1920s (5,000 acres (2,000 ha)) in Temple Terrace, Florida.

The Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival

editThe Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival is one of the nation's oldest, largest juried outdoor art festivals, rated among the top shows by Sunshine Artist and American Style magazines.[21] In 2012, about 1,200 artists from around the world applied for entry, and an independent panel of judges selected 225 national and international artists to attend the show. The National Endowment for the Arts, the White House, Congress, and many others have lauded the Festival for promoting art and art education in Central Florida. An all-volunteer board of directors runs the annual festival.[22]

Geography

editThe approximate coordinates for the City of Winter Park is located at 28°35′46″N 81°20′48″W / 28.59611°N 81.34667°W. The city is northeast of, and adjacent to Orlando. Elevation ranges between 66 and 97 feet (20 and 30 m) above sea level.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.2 square miles (26.3 km2), of which 8.7 square miles (22.5 km2) is land and 1.5 square miles (3.9 km2) (14.62%) is water.[23] It is nestled among the Winter Park Chain of Lakes, a series of lakes interconnected by a series of navigable canals, which were originally created for flood control and to run logs to a sawmill on present-day Lake Virginia. The lakes are popular for boating, watersports, fishing and swimming.

The city is traversed by the old East Florida and Atlantic Railroad ("Dinky Line") railroad bed, which until the 1960s had a stop at Lake Virginia/Rollins College at the city park now known as Dinky Dock. Much of this right of way has been converted to a rail-trail pedestrian/biking path in the form of the Cady Way Trail, which leads from Cady Way Park toward the Baldwin Park neighborhood and downtown Orlando, and in the opposite direction to Oviedo and beyond (via the Florida Trail), due to a new pedestrian bridge spanning Semoran Boulevard (SR 436) in Orange County.

SunRail operates a rail line through Winter Park on the former Atlantic Coast Line, with an Amtrak and SunRail commuter rail station in downtown's historic Central Park.

Climate

editThe climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild winters. According to the Köppen climate classification, the City of Winter Park has a humid subtropical climate zone (Cfa).

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 270 | — | |

| 1900 | 366 | 35.6% | |

| 1910 | 570 | 55.7% | |

| 1920 | 1,078 | 89.1% | |

| 1930 | 3,686 | 241.9% | |

| 1940 | 4,715 | 27.9% | |

| 1950 | 8,250 | 75.0% | |

| 1960 | 17,162 | 108.0% | |

| 1970 | 21,895 | 27.6% | |

| 1980 | 22,339 | 2.0% | |

| 1990 | 22,242 | −0.4% | |

| 2000 | 24,090 | 8.3% | |

| 2010 | 27,852 | 15.6% | |

| 2020 | 29,795 | 7.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[24] Florida Department of Agriculture[25] | |||

| Race | Pop 2010[26] | Pop 2020[27] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 22,755 | 21,852 | 81.70% | 73.34% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 2,034 | 2,055 | 7.30% | 6.90% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 35 | 40 | 0.13% | 0.13% |

| Asian (NH) | 632 | 1,061 | 2.27% | 3.56% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 5 | 8 | 0.02% | 0.03% |

| Some other race (NH) | 52 | 143 | 0.19% | 0.48% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 396 | 1,119 | 1.42% | 3.76% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,943 | 3,517 | 6.98% | 11.80% |

| Total | 27,852 | 29,795 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 29,795 people, 13,072 households, and 7,055 families residing in the city.[28]

As of the census of 2020, the population density was 3,401.6 inhabitants per square mile (1,283.97/km2). There were 14,073 housing units at an average density of 1,606.5 per square mile (620.3/km2).

In 2020, there were 13,072 households, out of which 22.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.0% were married couples living together, 33.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 7.3% were non-families. 33.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.22 and the average family size was 2.96.

In 2020, in the city the population was spread out, with 3.5% under the age of 5, 17.3% under the age of 18, 82.7% aged 18 years and over, and 22.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45.3 years.

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 27,852 people, 11,995 households, and 6,419 families residing in the city.[29]

Economy

editPersonal income

editAs of 2020, the median income for a household in the city was $80,500, and the median income for a family was $130,120. Males had a median income of $83,738 versus $58,277 for females. The per capita income for the city was $65,481. About 7.0% of families and 9.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.4% of those under age 18 and 10.2% of those age 65 or over.

However, also in 2020,[30] these incomes are very divided based on where you live within Winter Park. The area to the northeast of Park Ave is the most affluent part with an average household income of $44,000. There are still houses with significant higher incomes within these parts. The “Via” streets are one of the most affluent neighborhoods. This area includes the Isle of Sicily, a private drive that juts out into Lake Maitland with extremely expensive houses and residents such as Doc Rivers and Carrot Top. To the east of Park Ave, the area is slightly less affluent with an average household income of $32,000. Many of these are still very expensive lakefront properties. The lowest income area is to the west of Park Ave with an average household income of $23,000. Many of these houses include those built by the non-profit organization Habitat for Humanity. There is no local middle or elementary school for this area.

Tourism

editScenic Olde Winter Park area is punctuated by small, winding brick streets, and a canopy of old southern live oak and camphor trees, draped with Spanish moss. There are hundreds of thousands of visitors to annual festivals [31] including the Bach Festival, the nationally ranked Sidewalk Art Festival, and the Winter Park Concours d'Elegance. Winter Park is often seen as a popular tourist destination for those visiting Orlando that want an escape from the typical tourist scene of the Orlando theme parks. There is a quaint, local feel to the town even though there are a lot of tourists, especially during the winter months and holidays.

Within the city is the Mead Botanical Garden which is a 47.6 acres (19.3 ha) park that encompasses several ecosystems. It has an amphitheater, butterfly garden, discovery barn and a recreation center.[32] Many structures are more than 100 years old.[33]

Industry

editBonnier Corporation is based in Winter Park. D100 Radio was founded here and is still present in Winter Park.

According to the City's 2021 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[34] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AdventHealth Winter Park | 1,600 |

| 2 | Gecos Inc | 1,400 |

| 3 | Orange County Public Schools | 650 |

| 4 | Rollins College | 645 |

| 5 | City of Winter Park | 535 |

| 6 | Publix Super Markets | 300 |

Education

editWinter Park is served by Orange County Public Schools.

Elementary schools

editMiddle school

editHigh schools

editPrivate schools

edit- Chesterton Academy of Orlando

- St. Margaret Mary Catholic School (K-8)

- The Geneva School (K-12)

- The Parke House Academy

- Trinity Preparatory School

Higher learning

edit- Crealde School of Art[36]

- Fortis College, Winter Park Campus

- Full Sail University

- Rollins College

- Valencia College, Winter Park Campus

- Winter Park Tech

Transportation

editPublic Transit

edit- Lynx

- Winter Park station (SunRail/Amtrak)

Major Roads

editSites of interest

edit- Albin Polasek Museum and Sculpture Gardens

- All Saints Episcopal Church

- Annie Russell Theatre

- Casa Feliz Historic House Museum

- Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art

- Comstock-Harris House

- D100 Studio One (closed to the public)

- Downtown Winter Park Historic District

- Edward Hill Brewer House

- Hannibal Square

- Hannibal Square Heritage Center

- Knowles Memorial Chapel

- Kraft Azalea Park

- Lake Baldwin Park

- Mead Botanical Garden

- Mount Moriah Missionary Baptist Church

- Rollins Museum of Art

- Scenic Boat Tours off East Morse Boulevard

- St. Margaret Mary Catholic Church

- Winter Park Historical Museum[37]

- Winter Park Farmers' Market

- Winter Park Public Library[38]

- Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival

- Woman's Club of Winter Park

Notable people

edit- Dorothy Deming, nurse and author.

- George Eddy, US-French basketball player and basketball commentator.

- Theodore Miller Edison, youngest son of inventor Thomas Edison.[39]

- Samuel Gibbs French, Confederate Major General.

- Logan Gilbert, professional MLB baseball player.

- Bruce Magruder, US Army major general.[40]

- Dax McCarty, soccer player

- Chris McKay, film director.[41]

- Helen Monsch, Cornell University professor, died in Winter Park

- Stephanie Murphy, congressperson

- Moshe Reuven, Hasidic Billboard charting music artist and 30 Under 30 Tech entrepreneur

- Fred Rogers, television host and children's entertainer. Rogers graduated from Winter Park's Rollins College, where he also met his future wife, Joanne. In later years, they spent most winters in the town.[42]

- Austin Russell, billionaire tech CEO.[43]

- Willie Snead, professional NFL wide receiver

- Forrest Wall, professional MLB baseball player

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f "Winter Park Timeline". cityofwinterpark.org.

- ^ a b c d e f "Winter Park Florida, United States". Britannica.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ [1], Rollins College. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- ^ [2], Rollins College: Tuition & Fees. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- ^ "2023 Most Expensive Florida Colleges", College Tuition Prepare. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- ^ [3], Crummer Graduate School of Business. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- ^ Mooney, Anne (July 14, 2022). "Beware the Cock of the Walk". Winter Park Voice: A Policy & Issues News Magazine. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ "Peacock preserve". West Orange Times & Observer. August 12, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Robinson, Jim (December 27, 1987). "A Sinkhole Chronology". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

In letters to all of the mayors in Orange County, Henry Swanson, agricultural agent and resident layman expert on Central Florida water, warns that if local governments continue to allow too much water to be drawn from the ground and allow developers to cover the land with buildings and parking lots, they can expect sinkholes, especially in the west Winter Park area.

- ^ a b c Grove, Jim (November 15, 1996). "In 1981, World Was Riveted by the Saga of the Sinkhole". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

On Friday evening, May 8, 1981, Mae Rose Owens - now Mae Rose Williams - was playing with her dog, Muffin, in the front yard of her home on West Comstock Avenue on the west side of Winter Park when she heard a 'queer, swishing' noise.

- ^ "Pictures: Winter Park sinkhole". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

In 1981, Mae Rose Williams with her dog Muffin, the pooch who stood outside barking fiercely when the Winter Park sinkhole started to open.

- ^ a b c d e Rajtar, Gayle and Steve (May 2010). "That Sinking Feeling: When Mae Rose Owens heard a 'ploop' back in May 1981, she didn't realize just how big a hole she was in". Winter Park Magazine. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

When she looked outside, she saw a sycamore tree disappear as if it were being pulled downward by the roots, making a sound that she described as a 'ploop.'

- ^ "Winter Park sinkhole photo gallery". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Facts taken from original Langford Hotel property promotional material.

- ^ "Langford Hotel History". Wppl.org. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ "Rollins seeks developer, architect for proposed inn". Orlando Business Journal. February 8, 2010.

- ^ "THE BOUTIQUE HOTELS FLORIDA EXPERIENCE". The Alfond Inn. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ "Show Review Archives". Sunshine Magazine.

- ^ "51st Annual Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival". WFTV.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Winter Park city, Florida". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ Florida Department of Agriculture (1906). Census of the State of Florida. Urbana, I.L.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Winter Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Winter Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Winter Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Winter Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "The Opportunity Atlas". opportunityatlas.org.

- ^ Connolly, Patrick (March 17, 2022). "Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival returns with 215 artists on Park Avenue". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ "Mead Botanical Garden". City of Winter Park. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ "History of Mead Botanical Garden". Mead Botanical Garden. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ "City of Winter Park 2021 ACFR" (PDF). Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ "Aloma Elementary School". Eal.ocps.net. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ "Crealde School of Art". Crealde.org. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ "Winter Park Historical Association & Museum". Winterparkhistorical.com. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ "Winter Park Public Library". Wppl.org. December 6, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ McLeod, Emily (March 30, 2023). "Look inside historic Winter Park home of Tom Edison's son, now up for sale". WKMG. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ^ "General, 70, Dies Here; Long Career". Orlando Evening Sentinel. Orlando, FL. July 24, 1953. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Chris McKay". IMDb. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ^ Owen, Rob (March 18, 2022). "Spend a beautiful day in Mister Rogers' Florida neighborhood". TribLIVE.com. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ^ McClain, James (December 9, 2021). "Turns Out a 26-Year-Old Billionaire Bought That $83 Million Palisades House". DIRT. Retrieved May 13, 2023.