Wind power in Texas, a portion of total energy in Texas, consists of over 150 wind farms, which together have a total nameplate capacity of over 30,000 MW (as of 2020).[1][2] If Texas were a country, it would rank fifth in the world;[1] the installed wind capacity in Texas exceeds installed wind capacity in all countries but China, the United States, Germany and India. Texas produces the most wind power of any U.S. state.[1][3] According to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), wind power accounted for at least 15.7% of the electricity generated in Texas during 2017, as wind was 17.4% of electricity generated in ERCOT, which manages 90% of Texas's power.[4][5] ERCOT set a new wind output record of nearly 19.7 GW at 7:19 pm Central Standard Time on Monday, January 21, 2019.[6]

The wind resource in many parts of Texas is very large. Farmers may lease their land to wind developers, creating a new revenue stream for the farm. The wind power industry has also created over 24,000 jobs for local communities and for the state. Texas is seen as a profit-driven leader of renewable energy commercialization in the United States. The wind boom in Texas was assisted by expansion of the state’s Renewable Portfolio Standard, use of designated Competitive Renewable Energy Zones, expedited transmission construction, and the necessary Public Utility Commission rule-making.[7]

The Los Vientos Wind Farm (912 MW) in South Texas, is the state's largest wind farm. Other large wind farms in Texas include Roscoe Wind Farm, Horse Hollow Wind Energy Center, Sherbino Wind Farm, Capricorn Ridge Wind Farm, Sweetwater Wind Farm, Buffalo Gap Wind Farm, King Mountain Wind Farm, Desert Sky Wind Farm, Wildorado Wind Ranch, and the Brazos Wind Farm.

Overview

editWind power has a long history in Texas. West Texas A&M University began wind energy research in 1970 and led to the formation of the Alternative Energy Institute (AEI) in 1977. AEI has been a major information resource about wind energy for Texas.[8] The first 80-meter tower was erected at Big Spring, Texas in 1999.[9]

Several forces are driving the growth of wind power in Texas: favorable wind resources and land availability, State targets for renewable energy, cost efficiency of development and operation of wind farms, and a suitable electric transmission grid. The broad scope and geographical extent of wind farms in Texas is considerable: wind resource areas lie in the Texas Panhandle, along the Gulf coast south of Galveston, and in the mountain passes and ridge tops of the Trans-Pecos in the western tip of Texas. In 2012 over 10,700 wind turbines were operating in Texas to generate electricity, but 80,000 windmills were pumping water, indicating the amount of growth potential remaining for wind power generation.[10]

Wind power is a for-profit enterprise between land owners and wind farm operators. Texas farmers can lease their land to wind developers for either a set rental per turbine or for a small percentage of gross annual revenue from the project.[11] This offers farmers a fresh revenue stream without impacting traditional farming and grazing practices.[12] Although leasing arrangements vary widely, the U. S. Government Accountability Office reported in 2004 that a farmer who leases land to a wind project developer can generally obtain royalties of $3,000 to $5,000 per turbine per year in lease payments. These figures are rising as larger wind turbines are being produced and installed.[13]

Wind power offers a reliability benefit in that its generation (though not its transmission) is highly decentralized. Sabotage and industrial accidents can be potential threats to the large, centrally located, power plants that provide most of Texas’ electricity. Should one of these plants be damaged, repairs could take more than a year, possibly creating power shortages on a scale that Texans have never experienced before. Coal trains and gas pipelines are also vulnerable to disruption. However, wind power plants are quickly installed and repaired. The modular structure of a wind farm also means that if one turbine is damaged, the overall output of the plant is not significantly affected.[14]

Wind is a highly variable resource. With proper understanding and planning, it can be incorporated into an electric utility's generation mix, although it clearly does not provide the sort of on-demand availability that gas power stations provide.

Many areas in Texas have wind conditions allowing for development of wind power generation. The number of commercially attractive sites has expanded as wind turbine technology has improved and development costs continue to drop.[15] (→ Cost of electricity by source#United States) Particularly in southern Texas, the difference between land and off-shore air temperatures creates convection currents that generate significant winds during the middle of the day when electricity usage is typically at its peak level.[16] Although these winds are less than in West Texas, they occur more predictably, more in correlation with consumption, and closer to consumers. Several wind farms have been developed at the Texas coast, to a combined 3,000 MW.[17][18]

Starting in 2008, the wind power development boom in Texas outstripped the capacity of the transmission systems in place,[19] and predicted shortages in transmission capability could have dampened the growth of the industry. Until 2008, the growth in wind power "piggybacked" on existing lines, but had almost depleted spare capacity.[20] As a result, in winter the west Texas grid often had such a local surplus of power, that the price would fall below zero.[21][22] According to Michael Goggin, electric industry analyst at AWEA, "Prices fell below US −$30/MWh (megawatt-hour) on 63% of days during the first half of 2008, compared to 10% for the same period in 2007 and 5% in 2006."[23]

In July 2008, utility officials gave preliminary approval to a $4.9 billion plan to build new transmission lines to carry wind-generated electricity from West Texas to urban areas such as Dallas. The new plan would be the biggest investment in renewable energy in U.S. history, and would add transmission lines capable of moving about 18,000 megawatts.[24] ERCOT curtailed wind power by 17% (3.8 TWh) in 2009, but that decreased to only 0.5% by 2014, as transmission improved, particularly the Competitive Renewable Energy Zone (CREZ) in 2013.[25][26][27] However the CREZ lines are sometimes maxed out, and in November 2015, prices were negative for 50 hours.

In an early morning period of low electricity demand, wind energy served more than 56% of total demand on the ERCOT grid at 3:10 am Central Standard Time on Saturday, January 19, 2019.[6] Two days later, ERCOT set a new wind output record of nearly 19.7GW at 7:19 pm Central Standard Time on Monday, January 21, 2019.[6]

In areas where Smart Metering is commonly installed,[28] some utilities offer free electricity at night.[29]

In 2020, wind power surpassed coal in the total electricity balance of the state for the very first time, “the newest sign of the growing popularity of the renewable energy in fossil fuel heartland of America,” as per the Financial Times.[30]

Large wind farms in Texas

editLocation map

editRenewable Portfolio Standard

editAfter years of preparation,[31][32] the Texas Renewable Portfolio Standard was originally created by Senate Bill 7 and signed by Governor Bush in 1999,[33][34][35] which helped Texas eventually become the leading producer of wind powered electricity in the U.S.[36][37][38] The RPS was part of new laws that restructured the electricity industry. The Texas RPS mandated that utility companies jointly create 2000 megawatts (MW) of new renewable energy by 2009 based on their market share.[39] In 2005, Senate Bill 20, increased the state’s RPS requirement to 5,880 MW by 2015, of which, 500 MW must come from non-wind resources. The bill set a goal of 10,000 MW of renewable energy capacity for 2025, which was achieved 15 years early, in 2010.[40]

According to DSIRE.org, "In 1999 the Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUCT) adopted rules for the state's Renewable Energy Mandate, establishing a renewable portfolio standard (RPS), a renewable-energy credit (REC) trading program, and renewable-energy purchase requirements for competitive retailers in Texas. The 1999 standard called for 2,000 megawatts (MW) of new renewables to be installed in Texas by 2009, in addition to the 880 MW of existing renewables generation at the time. In August 2005, S.B. 20 increased the renewable-energy mandate to 5,880 MW by 2015 (about 5% of the state's electricity demand), including a target of 500 MW of renewable-energy capacity from resources other than wind. Wind accounts for nearly all of the current renewable-energy generation in Texas. The 2005 legislation also set a target of reaching 10,000 MW of renewable energy capacity by 2025.[40]

Qualifying renewable energy sources include solar, wind, geothermal, hydroelectric, wave or tidal energy, biomass, or biomass-based waste products, including landfill gas. Qualifying systems are those installed after September 1999. The RPS applies to all investor-owned utilities. Municipal and cooperative utilities may voluntarily elect to offer customer choice.

The PUCT established a renewable-energy credit (REC) trading program that began in July 2001 and will continue through 2019. Under PUCT rules, one REC represents one megawatt-hour (MWh) of qualified renewable energy that is generated and metered in Texas. A capacity conversion factor (CCF) is used to convert MW goals into MWh requirements for each retailer in the competitive market. The CCF was originally administratively set at 35% for the first two compliance years, but is now based on the actual performance of the resources in the REC-trading program for the previous two years. For the 2010 and 2011 the CCF will be 30.5%." Each retailer in Texas is allocated a share of the mandate based on that retailer’s pro rata share of statewide retail energy sales. The program administrator maintains a REC account for program participants to track the production, sale, transfer, purchase, and retirement of RECs. Credits can be banked for three years, and all renewable additions have a minimum of 10 years of credits to recover over-market costs. An administrative penalty of $50 per MWh was established for providers that do not meet the RPS requirements.

Future developments

editLike several Texas solar plants, some Texas wind power plants include storage, with more projects under construction.[42] One of the first such energy storage systems started as 36 MW in Notrees in December 2012. The system allows excess wind energy to be stored, making the output more predictable and less variable.[43][44]

If developed, the Tres Amigas HVDC link to the Western grid and the Eastern grid could allow more flexibility in importing and exporting power to and from Texas.[45]

A 300 MW offshore wind farm is planned for Galveston, and 2,100 MW for the Gulf Coast of Texas.[46] Making turbines that are able to yaw quickly could make them more likely to be able to survive a hurricane.[47]

Statistics

edit

|

|

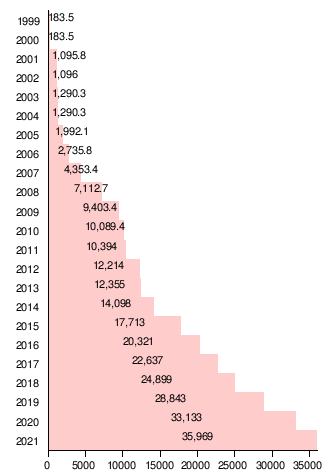

| Texas Wind Generation (GWh, Million kWh) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| 2001 | 1,187 | 84 | 142 | 88 | 115 | 103 | 92 | 76 | 56 | 76 | 123 | 89 | 143 |

| 2002 | 2,656 | 287 | 195 | 238 | 237 | 264 | 258 | 218 | 248 | 164 | 173 | 170 | 204 |

| 2003 | 2,569 | 171 | 190 | 215 | 260 | 209 | 213 | 240 | 193 | 196 | 168 | 228 | 286 |

| 2004 | 3,137 | 253 | 251 | 293 | 305 | 393 | 289 | 221 | 160 | 209 | 212 | 238 | 313 |

| 2005 | 4,238 | 312 | 209 | 350 | 432 | 385 | 451 | 309 | 261 | 315 | 348 | 325 | 541 |

| 2006 | 6,671 | 535 | 425 | 552 | 605 | 632 | 488 | 472 | 358 | 501 | 669 | 766 | 668 |

| 2007 | 9,007 | 498 | 712 | 757 | 798 | 596 | 577 | 436 | 867 | 741 | 1,057 | 944 | 1,024 |

| 2008 | 16,224 | 1,150 | 1,180 | 1,581 | 1,596 | 1,683 | 1,748 | 1,222 | 647 | 638 | 1,455 | 1,433 | 1,891 |

| 2009 | 20,026 | 1,656 | 1,719 | 1,905 | 2,028 | 1,520 | 1,613 | 1,394 | 1,458 | 1,218 | 1,933 | 1,802 | 1,780 |

| 2010 | 26,251 | 1,983 | 1,672 | 2,666 | 2,731 | 2,337 | 2,562 | 1,863 | 1,658 | 1,589 | 1,830 | 2,765 | 2,595 |

| 2011 | 30,547 | 2,064 | 2,528 | 2,689 | 3,066 | 3,099 | 3,357 | 2,085 | 1,955 | 1,694 | 2,671 | 2,832 | 2,507 |

| 2012 | 32,214 | 3,057 | 2,599 | 3,341 | 2,969 | 2,841 | 2,615 | 2,115 | 1,872 | 2,174 | 2,742 | 2,643 | 3,246 |

| 2013 | 36,415 | 2,656 | 2,984 | 3,810 | 3,761 | 3,963 | 3,379 | 2,938 | 2,130 | 2,005 | 3,082 | 3,030 | 2,677 |

| 2014 | 40,005 | 3,916 | 2,656 | 3,771 | 3,997 | 3,518 | 4,209 | 2,770 | 2,551 | 2,320 | 2,981 | 3,994 | 3,322 |

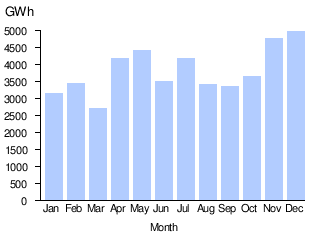

| 2015 | 44,883 | 3,031 | 3,268 | 2,544 | 4,099 | 4,371 | 3,411 | 4,059 | 3,218 | 3,465 | 3,661 | 4,772 | 4,984 |

| 2016 | 57,530 | 4,451 | 5,120 | 5,635 | 4,737 | 5,173 | 3,782 | 5,675 | 3,702 | 3,915 | 5,451 | 4,516 | 5,373 |

| 2017 | 67,061 | 5,873 | 5,828 | 7,095 | 6,929 | 6,310 | 4,839 | 4,511 | 3,694 | 4,754 | 6,003 | 5,895 | 5,330 |

| 2018 | 75,700 | 6,602 | 6,041 | 7,210 | 7,477 | 7,672 | 7,689 | 4,647 | 5,968 | 4,165 | 5,599 | 6,074 | 6,556 |

| 2019 | 83,621 | 6,925 | 6,639 | 6,694 | 7,839 | 7,762 | 6,290 | 6,731 | 6,489 | 6,517 | 7,455 | 6,990 | 7,290 |

| 2020 | 92,439 | 7,976 | 7,714 | 7,699 | 7,950 | 8,314 | 8,859 | 7,276 | 6,689 | 5,522 | 7,838 | 7,981 | 8,621 |

| 2021 | 100,057 | 7,945 | 6,349 | 10,749 | 9,496 | 9,458 | 7,363 | 5,796 | 7,615 | 7,088 | 8,930 | 8,967 | 10,301 |

| 2022 | 113,994 | 8,808 | 8,681 | 11,010 | 12,339 | 12,718 | 10,161 | 9,236 | 6,730 | 6,340 | 8,088 | 10,190 | 9,693 |

| 2023 | 119,836 | 11,860 | 11,131 | 12,388 | 11,385 | 8,445 | 8,979 | 9,897 | 8,783 | 8,126 | 9,785 | 8,827 | 10,229 |

| 2024 | 67,252 | 9,385 | 11,890 | 11,652 | 12,924 | 11,322 | 11,079 | ||||||

Green background indicates the largest wind generation month to date.

Source:[56][57][53]

|

|

|

|

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c AWEA Texas Fact Sheet Archived 2021-01-25 at the Wayback Machine (Q3 2020)

- ^ "Utility wind rush set to strengthen as low prices allow resource to spread across nation". Utility Dive. Archived from the original on 2019-08-19. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ a b "AWEA Third Quarter 2012 Market Report" (PDF). awea.org. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "ERCOT Quick Facts for 2017 published July 2018" (PDF). ercot.com. 2018-07-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-10. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ^ "ERCOT Quick Facts for 2017 published February 2018" (PDF). dropbox.com. 2018-02-01. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c "ERCOT Sets Record Wind Output and Penetration Rate Over the Holiday Weekend". TREIA-Texas Renewable Energy Industries Alliance. Archived from the original on 2019-08-18. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- ^ Lauren Glickman (25 August 2011). "Stetsons Off to Gov. Perry on Wind Power". Renewable Energy World.

- ^ "Alternative Energy Institute". Archived from the original on 2010-10-18. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ "Turbine timeline: The History of AWEA and the U.S. Wind Industry: 1990s." American Wind Energy Association. Retrieved 24 November 2015. AWEA website Archived 2015-11-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Roping the Breezes" (PDF). infinitepower.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ Krauss, Clifford (2008-02-23). "Move Over, Oil, There's Money in Texas Wind". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2009-04-01. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ Weise, Elizabeth; Jervis, Rick (October 18, 2019). "Turbines to the max: Texas produces more wind energy than nearly anywhere else in the world". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 2019-10-19. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ State Energy Conservation Office. The New Cash Crop Archived 2007-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SEED Coalition and Public Citizen’s Texas office (2002). Renewable Resources: The New Texas Energy Powerhouse Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine p. 11.

- ^ "Texas Wind Energy Resources". Archived from the original on 2007-07-22. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ "Texas Is Too Windy and Sunny for Old Energy Companies to Make Money". Bloomberg.com. 2017-06-20. Archived from the original on 2017-06-21. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ^ Handy, Ryan Maye (2017-07-27). "Sea change: Gulf Coast wind farms become vital to Texas energy mix". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- ^ "Duke Energy Renewables completes the final Los Vientos wind project in Texas | Duke Energy | News Center". News.duke-energy.com. 2016-08-03. Archived from the original on 2017-05-05. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ Bove, Tristan (March 22, 2022). "Texas has enough wind and solar power to phase out coal entirely. There's just one huge catch". finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ USA Today: Lines lacking to transmit wind energy Archived 2010-06-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Giberson, Michael (28 January 2009). "UPDATED: Negative power prices in the West region of ERCOT in 2008". Knowledge Problem. Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ^ Wang, Ucilia (10 December 2008). "Texas Wind Farms Paying People to Take Power". Greentech Media. Archived from the original on 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- ^ Goggin, Michael (19 September 2008). "Curtailment, Negative Prices Symptomatic of Inadequate Transmission". Renewable Energy World. Archived from the original on 2011-08-16. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ^ "Texas Will Spend Billions on Transmission of Wind Power". Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Wiser, Ryan H., and Mark Bolinger. "2014 Wind Technologies Market Report Archived 2015-09-14 at the Wayback Machine" page 38. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, August 2015.

- ^ Wiser, Ryan H., Eric Lantz, Mark Bolinger, and Maureen M. Hand. "Recent Developments in the Levelized Cost of Energy from U.S. Wind Power Projects Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine" page 12. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2012. Header page Archived 2015-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-18. Retrieved 2016-04-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Scope of Competition in Electric Markets in Texas". Public Utility Commission of Texas. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ CLIFFORD KRAUSS and Diane Cardwell (8 November 2015). "A Texas Utility Offers a Nighttime Special: Free Electricity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ a b Wind power overtakes coal in Texas electricity generation Archived 2021-01-10 at the Wayback Machine, Financial Times]

- ^ "Texas passes law for big renewable energy portfolio". www.windpowermonthly.com. 1 July 1999. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017.

- ^ Kate Galbraith, Asher Price (2013). The Great Texas Wind Rush. University of Texas Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780292748804.

we like wind. Go get smart on wind

- ^ SB7 Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine Law text Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback MachineTexas Legislature Online, May 1999. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ "Texas Renewable Portfolio Standard". Texas State Energy Conservation Office. Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ "Texas Renewable Portfolio Standard". Pew Center on Global Climate Change. September 24, 2011. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008.

- ^ Koronowski, Ryan. It's Not Just Oil: Wind Power Approaches 8% of Texas Electricity in 2010 Repower America, January 19, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ Galbraith, Kate; Price, Asher (August 2011). "A mighty wind". Texas Monthly. p. 5. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ "Swift Boats and Texas Wind". Windsector.tumblr.com. July 28, 2011. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ^ HURLBUT, DAVID (2008). "A Look Behind the Texas Renewable Portfolio Standard: A Case Study". Natural Resources Journal. 48 (1): 129–161. JSTOR 24889202. Archived from the original on 2020-11-04. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ a b Amory B. Lovins (2011). Reinventing Fire. p. 218.

- ^ "Wind energy production in Texas to outpace coal in 2020". Insider.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-20. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ Bedeschi, Beatrice (19 May 2021). "Enel to build longer wind battery in Texas to boost returns". Reuters Events. Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021.

- ^ Patterson, Lindsay (20 April 2011). "West Texas Project Could Change Future of Wind Power". texastribune.org. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ Duke Energy. "Duke Energy Renewables completes Notrees Battery Storage Project in Texas; North America's largest battery storage project at a wind farm". Duke Energy. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ "Tres Amigas". www.tresamigasllc.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Texas Offshore Wind Project Eyes Test Turbine by End of 2011". offshorewindwire.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "Wind Turbines Can Be Strengthened Against Hurricanes". riskandinsurance.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "AWEA Fourth Quarter 2016 Market Report". American Wind Energy Association. January 26, 2017. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ "AWEA Fourth Quarter 2017 Market Report". American Wind Energy Association. January 28, 2018. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ "WINDExchange: U.S. Installed and Potential Wind Capacity and Generation". Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ "Market Report 2021". American Clean Power Association. May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ "Generation Annual". U.S. Department of Energy. July 10, 2012. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ a b "U.S. EIA, Electric Power Monthly". U.S. Department of Energy. February 25, 2017. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. EIA, Electricity Data Browser". U.S. Department of Energy. July 5, 2018. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ "WINDExchagne: Wind Energy in Texas". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ EIA (July 23, 2013). "Electric Power Monthly Table 1.17.A." United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ^ EIA (July 23, 2013). "Electric Power Monthly Table 1.17.B." United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 2013-05-29. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

External links

edit- Current Texas wind generation maps, capacity, ordinances, and more from Energy.gov

- Compressed air storage

- Actual and predicted wind power

- Wind Power Helps Texas Move Past Oil[usurped]

- Texas oil tycoon plans largest wind farm

- Wind power experts say Texas grid needs work

- Wind energy in Texas – Reasons for success

- Head, Christopher (February 9, 2011). "The Curious Case of the Texas Wind Industry". The Energy Collective. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- Every wind farm of Texas @The Wind Power

- ERCOT Forecasted and Actual Wind Power Production