| Viral meningitis | |

|---|---|

| |

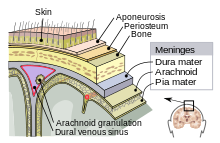

| Viral meningitis causes inflammation of the meninges |

Viral meningitis is a type of meningitis due to a viral infection. It is also referred to as aseptic meningitis. It results in inflammation of the meninges (the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord). Symptoms commonly include headache, fever, sensitivity to light, and neck stiffness.[1]

Viruses are the most common cause of aseptic meningitis.[2] Most cases of viral meningitis are caused by enteroviruses (common stomach viruses).[3][4][5] However, other viruses can also cause viral meningitis. For instance, West Nile virus, mumps, measles, herpes simplex types I and II, varicella, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCM) virus.[4][6] Based on clinical symptoms, viral meningitis cannot be reliably differentiated from bacterial meningitis, although viral meningitis typically follows a more benign clinical course. Viral meningitis has no evidence of bacteria present in cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). Therefore, lumbar puncture with CSF analysis is often needed to identify the disease.[7]

In most causes there is no specific treatment, with efforts generally aimed at relieving symptoms (headache, fever, or nausea).[8] A few viral causes, such as HSV, have specific treatments.

In the United States viral meningitis is the cause of greater than half of all cases of meningitis.[9]

Mechanism

editViral Meningitis is mostly caused by an infectious agent that has colonized somewhere in its host.[10] People who are already in an immunocompromised state are at the highest risk of pathogen entry.[11] Potential sites for this include the skin, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, nasopharynx, and genitourinary tract. The organism invades the submucosa at these sites by invading host defenses, such as local immunity, physical barriers, and phagocytes or macrophages.[10] After pathogen invasion, the immune system is activated.[12] An infectious agent can enter the central nervous system and cause meningeal disease via invading the bloodstream, a retrograde neuronal pathway, or by direct contiguous spread.[13] Immune cells and damaged endothelial cells release matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), cytokines, and nitric oxide. MMPs and NO induce vasodilation in the cerebral vasculature. Cytokines induce capillary wall changes in the blood brain barrier, which leads to expression of more leukocyte receptors, thus increasing white blood cell binding and extravasation. [11]

The barrier that the meninges create between the brain and the bloodstream are what normally protect the brain from the body's immune system. Damage to the meninges and endothelial cells increases cytotoxic reactive oxygen species production, which damages pathogens as well as nearby cells.[11] In meningitis, the barrier is disrupted, so once viruses have entered the brain, they are isolated from the immune system and can spread.[14] This leads to elevated intracranial pressure, cerebral edema, meningeal irritation, and neuronal death.[11]

Signs and symptoms

editViral meningitis characteristically presents with fever, headache and neck stiffness.[15] Fever is the result of cytokines released that affect the thermoregulatory neurons of the hypothalamus. Cytokines and increased intracranial pressure stimulate nociceptors in the brain that lead to headaches. Neck stiffness is the result of inflamed meninges stretching due to flexion of the spine.[11] In contrast to bacterial meningitis, symptoms are often less severe and do not progress as quickly.[15] Nausea, vomiting and photophobia (light sensitivity) also commonly occur, as do general signs of a viral infection, such as muscle aches and malaise.[15] Increased cranial pressure from viral meningitis stimulates the area postrema, which causes nausea and vomiting. Photophobia is due to meningeal irritation.[11] In severe cases, people may experience concomitant encephalitis (meningoencephalitis), which is suggested by symptoms such as altered mental status, seizures or focal neurologic deficits.[16]

Of note, infants with viral meningitis may only appear irritable, sleepy or have trouble eating.[7] In severe cases, people may experience concomitant encephalitis (meningoencephalitis), which is suggested by symptoms such as altered mental status, seizures or focal neurologic deficits.[16] The pediatric population may show some additional signs and symptoms that include jaundice and bulging fontanelles.[11]

Causes and Prevention

editThe most common causes of viral meningitis in the United States are non-polio enteroviruses. The viruses that cause meningitis are typically acquired from sick contacts. However, in most cases, people infected with viruses that may cause meningitis do not actually develop meningitis.[7]

Viruses that can cause meningitis include:[17]

- Enteroviruses

- Enterovirus 71

- Echovirus

- Poliovirus (PV1, PV2, PV3)

- Coxsackie A virus (CAV); also causes Hand foot and mouth disease

- Herpesviridae (HHV)

- Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1 / HHV-1) or type 2 (HSV-2 / HHV-2); also cause cold sores or genital herpes

- Varicella zoster (VZV / HHV-3); also causes chickenpox and shingles (herpes zoster)

- Epstein–Barr virus (EBV / HHV-4); also causes infectious mononucleosis/"mono"

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV / HHV-5)

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); causes AIDS

- La Crosse virus

- Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)

- Measles

- Mumps

- St. Louis encephalitis virus

- West Nile virus

Diagnosis

editThe diagnosis of viral meningitis is made by clinical history, physical exam, and several diagnostic tests.[18] Most importantly, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is collected via lumbar puncture (also known as spinal tap). This fluid, which normally surrounds the brain and spinal cord, is then analyzed for signs of infection.[19] CSF findings that suggest a viral cause of meningitis include an elevated white blood cell count (usually 10-100 cells/µL) with a lymphocytic predominance in combination with a normal glucose level.[20] Increasingly, cerebrospinal fluid PCR tests have become especially useful for diagnosing viral meningitis, with an estimated sensitivity of 95-100%.[21] Additionally, samples from the stool, urine, blood and throat can also help to identify viral meningitis.[19]

In certain cases, a CT scan of the head should be done before a lumbar puncture such as in those with poor immune function or those with increased intracranial pressure.[1]

Treatment and Prognosis

editIn viral meningitis, the treatment is supportive. Rest, hydration, antipyretics, and pain or anti-inflammatory medications may be given as needed.[22]

Herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus and cytomegalovirus have a specific antiviral therapy to avoid; most other viruses do not. For herpes the treatment of choice is aciclovir.[23]

Surgical management is indicated where there is extremely increased intracranial pressure, infection of an adjacent bony structure (e.g. mastoiditis), skull fracture, or abscess formation.[11]

The majority of people that have viral meningitis get better within 7-10 days.[24]

Recent Research

editFrom 1988–1999, about 36,000 cases occurred each year.[25] While the disease can occur in both children and adults, it is more common in children.[1] During an outbreak in Romania and in Spain viral meningitis was more common among adults.[26] While, people aged younger than 15 made up 33.8% of cases.[26] In contrast in Finland in 1966 and in Cyprus in 1996, Gaza 1997, China 1998 and Taiwan 1998, the incidences of viral meningitis were more common among children.[27][28][29][30]

It has been proposed that viral meningitis might lead to inflammatory injury of the vertebral artery wall.[31]

Viral meningitis is certainly a public health concern, but there is limited data on the epidemiology of it. A study was conducted to analyze the longterm and seasonal trends of this illness in young adult military population of the Israel Defense Forces. Cases of viral meningitis from January 1, 1978 to December 31, 2012 were analyzed.[32] Observation of the long-term epidemiology of viral meningitis shows an epidemic pattern, with predominance in the warmer months. These results indicate that identifying viral causes of meningitis may spare patients unnecessary treatment, while prompting the introduction of public health interventions and control measures, especially in crowded settings.[32]

The Meningitis Research Foundation is currently conducting a study to see if new genomic techniques can the speed, accuracy and cost of diagnosing meningitis in children in the UK. The research team will develop a new method to be used for the diagnosis of meningitis, analysing the genetic material of microorganisms found in CSF (cerebrospinal fluid). The new method will first be developed using CSF samples where the microorganism is known, but then will be applied to CSF samples where the microorganism is unknown (estimated at around 40%) to try and identify a cause.[33]

References

edit- ^ a b c Logan, SA; MacMahon, E (5 January 2008). "Viral meningitis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 336 (7634): 36–40. PMID 18174598.

- ^ "Aseptic Meningitis". Healthline. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ "Epidemiology". Alaska Department of Health and Social Services.

- ^ a b Logan, SA; MacMahon, E (Jan 5, 2008). "Viral meningitis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 336 (7634): 36–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.39409.673657.ae. PMC 2174764. PMID 18174598.

- ^ Ratzan, K. R. (1985-03-01). "Viral meningitis". The Medical Clinics of North America. 69 (2): 399–413. ISSN 0025-7125. PMID 3990441.

- ^ "Acute Communicable Disease Control". lacounty.gov.

{{cite web}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help) - ^ a b c "Meningitis | Viral | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-02.

- ^ "Viral Meningitis - Meningitis Research Foundation". www.meningitis.org. Retrieved 2017-03-02.

- ^ Bartt, R (December 2012). "Acute bacterial and viral meningitis". Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 18 (6 Infectious Disease): 1255–70. PMID 23221840.

- ^ a b "Viral Meningitis: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 2017-11-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h "Meningitis | McMaster Pathophysiology Review". www.pathophys.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "Meningitis | McMaster Pathophysiology Review". www.pathophys.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ Klimpel, Gary R. (1996). Baron, Samuel (ed.). Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 0963117211. PMID 21413332.

- ^ Chadwick, D. R. (2005-01-01). "Viral meningitis". British Medical Bulletin. 75–76 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh057. ISSN 0007-1420.

- ^ a b c "Viral Meningitis - Brain, Spinal Cord, and Nerve Disorders - Merck Manuals Consumer Version". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ a b Cho, Tracey A.; Mckendall, Robert R. (2014-01-01). Booss, Alex C. Tselis and John (ed.). Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Neurovirology. Vol. 123. Elsevier. pp. 89–121.

- ^ Viral Meningitis at eMedicine

- ^ "Diagnosis - Meningitis - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ a b "CSF analysis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ "CSF Analysis - Neurology - UMMS Confluence". wiki.umms.med.umich.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ Fomin, Dean A. Seehusen|Mark Reeves|Demitri. "Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis - American Family Physician". www.aafp.org. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ "Viral Meningitis Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmacologic Treatment and Medical Procedures, Patient Activity". 2017-11-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Tyler KL (June 2004). "Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: encephalitis and meningitis, including Mollaret's". Herpes. 11 (Suppl 2): 57A–64A. PMID 15319091.

- ^ "Meningitis | Viral | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- ^ Khetsuriani, N; Quiroz, ES; Holman, RC; Anderson, LJ (Nov–Dec 2003). "Viral meningitis-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1988–1999". Neuroepidemiology. 22 (6): 345–52. doi:10.1159/000072924. PMID 14557685.

- ^ a b Jiménez Caballero, PE; Muñoz Escudero, F; Murcia Carretero, S; Verdú Pérez, A (Oct 2011). "Descriptive analysis of viral meningitis in a general hospital: differences in the characteristics between children and adults". Neurologia (Barcelona, Spain). 26 (8): 468–73. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2010.12.004. PMID 21349608.

- ^ Rantakallio, P; Leskinen, M; von Wendt, L (1986). "Incidence and prognosis of central nervous system infections in a birth cohort of 12,000 children". Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 18 (4): 287–94. doi:10.3109/00365548609032339. PMID 3764348.

- ^ "1998—Enterovirus Outbreak in Taiwan, China—update no. 2". WHO.

- ^ "1997—Viral meningitis in Gaza". WHO.

- ^ "1996—Viral meningitis in Cyprus". WHO.

- ^ Pan, Xudong. "Vertebral artery dissection associated with viral meningitis". BMC Neurology. 12.

- ^ a b Levine, Hagai; Mimouni, Daniel; Zurel-Farber, Anat; Zahavi, Alon; Molina-Hazan, Vered; Bar-Zeev, Yael; Huerta-Hartal, Michael (July 2014). "Time trends of viral meningitis among young adults in Israel: 1978-2012". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases: Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 33 (7): 1149–1153. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2057-3. ISSN 1435-4373. PMID 24463724.

- ^ "Using new genomic techniques to identify the causes of meningitis in UK children | Meningitis Research Foundation". www.meningitis.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.