The Seattle metropolitan area is an urban conglomeration in the U.S. state of Washington that comprises Seattle, its surrounding satellites and suburbs. The United States Census Bureau defines the Seattle–Tacoma–Bellevue, WA metropolitan statistical area as the three most populous counties in the state: King, Pierce, and Snohomish. Seattle has the 15th largest metropolitan statistical area (MSA) in the United States with a population of 4,018,762 as of the 2020 census, over half of Washington's total population.

Seattle metropolitan area | |

|---|---|

| Seattle–Tacoma–Bellevue, WA MSA | |

Aerial view of Downtown Seattle, 2024 | |

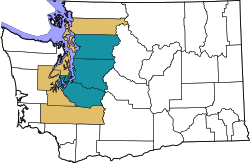

Map of the Seattle MSA, highlighted in teal; the Seattle CSA is highlighted in gold | |

| Coordinates: 47°29′N 121°50′W / 47.49°N 121.83°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Counties (MSA) | King, Pierce, Snohomish |

| Largest city | Seattle (762,500) |

| Other cities | |

| Government | |

| • Congressional districts | 1st, 2nd, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th |

| Area | |

• Total | 6,308.67 sq mi (16,339.4 km2) |

| • Land | 5,869.72 sq mi (15,202.5 km2) |

| • Water | 438.95 sq mi (1,136.9 km2) |

| Highest elevation | Mount Rainier 14,411 ft (4,392 m) |

| Lowest elevation | Sea level 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 4,018,762 |

• Estimate (2023)[3] | 4,044,837 |

| • Rank | 15th in the U.S. |

| • Density | 685/sq mi (264/km2) |

| GDP | |

| • MSA | $517.803 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code prefixes[5] | 980, 981, 982, 983, 984 |

| Area codes | 206, 253, 360, 425, 564 |

| FIPS code[6] | 53-42660 |

The area is considered part of the greater Puget Sound region, which largely overlaps with the Seattle Combined Statistical Area (CSA). The Seattle metropolitan area is home to a large tech industry and is the headquarters of several major companies, including Microsoft and Amazon. The area's geography is varied and includes the lowlands around Puget Sound and the Cascade Mountains; the highest peak in the metropolitan area is Mount Rainier, which has a summit elevation of 14,411 feet (4,392 m) and is one of the tallest mountains in the United States.

Definition

editAs defined by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Office of Management and Budget, the Seattle metropolitan area is officially the Seattle–Tacoma–Bellevue, WA metropolitan statistical area (MSA) and consists of:[7][8]

- Everett metropolitan division

- Snohomish County: north of Seattle

- Seattle–Bellevue–Kent metropolitan division

- King County: Seattle and its immediate vicinity

- Tacoma–Lakewood metropolitan division

- Pierce County: south of Seattle

Based on commuting patterns, the adjacent metropolitan areas of Olympia, Bremerton, and Mount Vernon, along with a few smaller satellite urban areas, are grouped together in a wider labor market region known as the Seattle–Tacoma combined statistical area (CSA), which encompasses most of the Puget Sound region.[8][9] The population of this wider region was 4,953,389 at the 2020 census and estimated to be 4,993,725 in 2023;[3] the Puget Sound region is home to two-thirds of Washington's population.[10] The Seattle CSA is the 14th largest in the United States and the 13th largest primary census statistical area in the country.[3] The additional metropolitan and micropolitan areas included are:[8]

- Bremerton–Silverdale–Port Orchard metropolitan area

- Kitsap County: west of Seattle, separated from the city by Puget Sound

- Centralia micropolitan area

- Lewis County: south of Olympia

- Mount Vernon–Anacortes metropolitan area

- Skagit County: north of Everett

- Oak Harbor micropolitan area

- Island County: northwest of Everett, encompassing Whidbey Island and Camano Island in Puget Sound

- Olympia–Lacey–Tumwater metropolitan area

- Thurston County: southwest of Seattle, at the south end of Puget Sound

- Shelton micropolitan area

- Mason County: west of Tacoma and northwest of Olympia

Establishment and expansion

editThe Census Bureau adopted metropolitan districts in the 1910 census to create a standard definition for urban areas with industrial activity around a central city.[11] At the time, Seattle had the 22nd largest metropolitan district population at 239,269 people, a 195.8 percent increase from the population of the equivalent area in the 1900 census.[12] The Seattle metropolitan district was expanded to encompass the entirety of Lake Washington in the 1930 census and also included Edmonds in Snohomish County, Des Moines in southern King County, and portions of eastern Bainbridge Island in Kitsap County.[13] The district covered 209.9 square miles (544 km2), of which two-thirds was outside of Seattle proper, and counted a population of 420,663.[14]

The Seattle metropolitan area, successor to the metropolitan district, was expanded in 1949 to encompass all of King County but lose its portions in Kitsap and Snohomish counties. The local chamber of commerce and other leaders had lobbied for a definition that also included all of Kitsap, Pierce, and Snohomish counties in a manner similar to the Portland metropolitan area, which had been expanded to cover four counties in Oregon and southwestern Washington.[15][16] The Bureau of the Budget (now Office of Management and Budget) added Snohomish County to its definition of the Seattle metropolitan area in 1959. The definition had previously only encompassed King County; local leaders had sought to also include Pierce and Kitsap counties in a "Puget Sound metropolitan area".[17] Snohomish County had protested its inclusion and had sought a separate metropolitan area designation centered on Everett, which did not meet the population threshold of 50,000 residents.[18][19]

In the 1950 census, a separate metropolitan area for Tacoma was defined that encompassed all of Pierce County.[20][21] Kitsap County remained part of no metropolitan area despite its connections to both Seattle and Tacoma.[22] The Office of Management and Budget included the area in the Seattle–Tacoma standard consolidated statistical area in 1981;[23] it was replaced in 1983 by the Seattle–Tacoma consolidated metropolitan statistical area (CMSA).[24] The CMSA was expanded to include Bremerton and Olympia after the 1990 census and was the 12th largest in the country at the time.[25][26] The Office of Management and Budget restructured its classification system in 2003 and created the Seattle–Tacoma–Bellevue metropolitan statistical area to cover the tri-county region. A new Seattle–Tacoma–Olympia combined statistical area (CSA) replaced the CMSA and expanded to cover Island and Mason counties.[27][28] The Mount Vernon–Anacortes metropolitan area was created in 2003 to encompass Skagit County and added to the Seattle CSA in 2006;[29][30] the CSA was extended further south to Lewis County through the addition of the Centralia micropolitan area in 2013.[31]

Geography

editThe Seattle metropolitan area covers 6,309 square miles (16,340 km2) of land and water in Western Washington divided between the three counties;[1] King County is the largest county at over 2,115 square miles (5,480 km2), followed by Snohomish and Pierce counties.[32] The region includes portions of the Cascade Range and several active volcanoes, including Mount Rainier and Glacier Peak, which can generate lahars that reach populated areas.[33][34] The summit of Mount Rainier is the tallest point in Washington at 14,411 feet (4,392 m) above mean sea level;[32] it has 26 glaciers that are visible from much of the region's lowlands.[33][35] To the west of the metropolitan area is Puget Sound, which forms the second-largest saltwater estuary in the United States and is part of the Salish Sea.[36]

Cities

edit- Principal cities[8]

- Other cities[37]

- Arlington

- Bainbridge Island

- Beaux Arts Village

- Bonney Lake

- Bothell

- Bremerton

- Brier

- Buckley

- Burien

- Covington

- Des Moines

- Duvall

- Enumclaw

- Edmonds

- Gig Harbor

- Gold Bar

- Granite Falls

- Issaquah

- Kenmore

- Kirkland

- Lake Forest Park

- Lake Stevens

- Lynnwood

- Maple Valley

- Marysville

- Mercer Island

- Mill Creek

- Monroe

- Mountlake Terrace

- Mount Vernon

- Mukilteo

- Newcastle

- Normandy Park

- North Bend

- Olympia

- Orting

- Puyallup

- Poulsbo

- Sammamish

- SeaTac

- Shoreline

- Silverdale

- Snohomish

- Snoqualmie

- Stanwood

- Sultan

- Sumner

- Tukwila

- Woodinville

- Woodway

Indian reservations

editThe Seattle metropolitan area is home to nine federally recognized tribes that belong to the indigenous Coast Salish peoples:[38]

- Muckleshoot Indian Tribe

- Nisqually Indian Tribe

- Port Gamble Band of S'Klallam Indians

- Puyallup Indian Tribe

- Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe

- Snoqualmie Indian Tribe

- Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians

- Suquamish Indian Tribe

- Tulalip Tribes

The tribes have sovereign governments that have authority over their enrolled members and the Indian reservations that were established in the region.[38] The reservations were created through treaties with the federal government that were not consistently honored and often combined several tribes together;[39] they were also open to settlement by non-Indians.[40]

Military installations

editThe Puget Sound region has approximately 83,705 U.S. Department of Defense personnel, including active duty members of the military and civilian workers at United States Armed Forces bases.[41][42] Major facilities in the area include Joint Base Lewis–McChord in Pierce County, the largest military base on the West Coast with over 25,000 active duty soldiers;[43] Naval Station Everett in Snohomish County; and Naval Air Station Whidbey Island in Island County.[41][44] The Kitsap Peninsula—part of the Seattle CSA—is home to Naval Base Kitsap, which includes the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton and Naval Submarine Base Bangor,[44] site of the third-largest arsenal of nuclear weapons in the world with more than 1,100 warheads for submarines.[45]

The region also has several major companies that serve as defense contractors for the U.S. military, comprising most of Washington's $6.9 billion awarded in fiscal year 2022. The largest contractors in the Seattle area include Boeing, PacMed, and Microsoft.[41][46] The Veterans Health Administration has 110,000 enrolled patients in the Puget Sound region, which includes a large population of retirees.[47]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 4,128 | — | |

| 1880 | 11,616 | 181.4% | |

| 1890 | 123,443 | 962.7% | |

| 1900 | 189,518 | 53.5% | |

| 1910 | 464,659 | 145.2% | |

| 1920 | 601,090 | 29.4% | |

| 1930 | 706,220 | 17.5% | |

| 1940 | 775,815 | 9.9% | |

| 1950 | 1,120,448 | 44.4% | |

| 1960 | 1,428,803 | 27.5% | |

| 1970 | 1,832,896 | 28.3% | |

| 1980 | 2,093,112 | 14.2% | |

| 1990 | 2,559,164 | 22.3% | |

| 2000 | 3,043,878 | 18.9% | |

| 2010 | 3,439,809 | 13.0% | |

| 2020 | 4,018,762 | 16.8% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 4,044,837 | 0.6% | |

| Calculated from county totals;[48] U.S. Census estimates[3] | |||

As of the 2020 census, there were 4,018,762 people in the three counties that form the Seattle metropolitan area, which comprises 52 percent of Washington's population.[2][49] It is the 15th largest metropolitan statistical area in the United States and among the fastest-growing in the country.[50] The overall population density was 685 inhabitants per square mile (264.5/km2). The population was 49.9% male and 50.1% female with a median age of 37.2 years old.[2]

The racial makeup of the metropolitan area was 60.1% White, 15.4% Asian, 6.1% Black, 1.1% Native American or Alaska Native, 1.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 11.0% from two or more races, and 5.3% from other races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race formed 11.2% of the population.[2] From 2010 to 2020, the non-Hispanic White population of the Seattle metropolitan area declined from 68 percent to 58 percent—the largest decline in the U.S.[51] The region also has a large Asian American population that was among the fastest-growing in the country between 2010 and 2020.[51][52]

There were 1,564,432 total households in the metropolitan area at the time of the 2020 census, of which 47.8% included a married couple, 8.1% included an unmarried cohabiting couple, 19.7% had a single male with no spouse or partner, and 24.4% single female with no spouse or partner. Out of all households, 29.8% had people under the age of 18 and 25.3% had people 65 years or older.[2] Approximately 18.3% of household residents were opposite-sex spouses, while 0.3% were same-sex spouses.[2]

According to a 2022 survey by the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 17 percent of adult residents in the Seattle metropolitan area identified as LGBTQ.[53] The region has one of the highest percentages of same-sex couples in the United States at 1.3 percent of households in the metropolitan area.[54]

Counties

editKing County is the largest of the three counties in the metropolitan area with 2,269,675 people in 2020, or 56 percent of the population of the Seattle area.[55]

| County | 2020 census[55] | 2010 census[55] | Change | Area | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King County | 2,269,675 | 1,931,249 | +17.52% | 2,115.56 sq mi (5,479.3 km2) | 1,035/sq mi (399/km2) |

| Pierce County | 921,130 | 795,225 | +15.83% | 1,669.51 sq mi (4,324.0 km2) | 552/sq mi (213/km2) |

| Snohomish County | 827,957 | 713,335 | +16.07% | 2,087.27 sq mi (5,406.0 km2) | 397/sq mi (153/km2) |

| Total | 4,018,762 | 3,439,809 | +16.83% | 5,869.72 sq mi (15,202.5 km2) | 685/sq mi (264/km2) |

Religion

editThe Seattle metropolitan area has one of the largest populations of people in the United States who identify as nonreligious.[56] A 2024 Household Pulse Survey from the United States Census Bureau estimated that 64 percent of adults in the area do not attend religious services more than once a year, the highest percentage among large U.S. metropolitan areas.[57] According to the Pew Research Center's 2014 U.S. Religious Landscape Study, the Seattle metropolitan area's religious affiliation is as follows:[58]

| Religious composition | 2014 |

|---|---|

| Christian | 52% |

| —Evangelical Protestant | 23% |

| —Mainline Protestant | 10% |

| —Black Protestant | 1% |

| Catholic | 15% |

| Non-Christian Faiths | 10% |

| —Jewish | 1% |

| —Muslim | < 1% |

| —Buddhist | 2% |

| —Hindu | 2% |

| Unaffiliated | 37% |

| Don't know | 1% |

Income and wealth

editThe cost of living in the Seattle area ranks among the highest in the United States among urban areas, particularly for housing, services, and retail goods.[59] In 2022, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that median household income for residents of the Seattle metropolitan area was $101,700, an 8.2 percent increase from 2019. It is the fourth-highest figure for any metropolitan area in the United States, behind San Jose, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.[60] The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated that the per-capita income of a Seattle metropolitan area resident was $92,113 in 2022;[61] the previous year, the region ranked tenth in the U.S. for per-capita income.[62]

The area is home to several of the wealthiest people in the United States and the world by net worth. Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos both held the title of world's richest person, as determined by Forbes, while living in the Eastside city of Medina.[63][64] Another Eastside suburb, Sammamish, has a median household income of $201,370—the second-highest among cities in the United States.[65] According to a 2024 study by Henley & Partners, the city of Seattle has an estimated 54,200 millionaires—ranking seventh in the United States by number of millionaires—and 11 billionaires.[66]

Housing and homelessness

editThe Seattle area has a housing shortage that has contributed to affordability issues in the early 21st century, particularly due to demand outpacing construction of new units.[67] The metropolitan area had the seventh highest number of new units built among large cities in 2016, of which 63 percent were in multifamily buildings.[68] The state legislature passed a new housing law in 2023 that allows for medium-density units in areas of all cities that supersede local zoning regulations; the new law could allow for 75,000 to 150,000 new units in the region, but exempts certain pre-existing homeowner associations and other contract-based communities.[69][70] As of April 2023[update], the median price for a single-family home was $722,000 and the median rent for a one-bedroom unit is $1,505 across the metropolitan area.[71][72] In King County, an estimated 309,000 new units are needed by 2044 to handle anticipated growth.[73] As of the 2020 census, the Seattle metropolitan area had 1,650,246 total housing units, of which 94.8% were occupied. Of the 85,814 vacant units, 41.1% were for rent, 4.4% were rented but not occupied, 10.1% were for sale, 5.1% had been sold but not yet occupied, and 16.9% were designated for seasonal or recreational use.[2]

King County has the third largest population of homeless or unsheltered people in the United States according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).[74] The agency's January 2023 report, based on the point-in-time count system, estimates 14,149 people in the county have experienced homelessness;[75] the King County Regional Homelessness Authority adopted a different methodology based on the number of people seeking services and estimated that 53,532 people in the county had been homeless at some point in 2022.[74][76] According to a survey collected by service providers for the county government, 68.5 percent of respondents said they last had stable housing in King County and 10.8 percent had lived elsewhere in the state.[77] Approximately 57 percent of the homeless population counted by HUD in King County was classified as unsheltered, either living in vehicles, encampments in public spaces, or other places.[78] The number of unsheltered individuals increased significantly in the late 2010s, leading to clearing of encampments and other structures by local governments.[79][80]

The county has 5,115 emergency shelter beds and tiny house villages, of which 67 percent are in the city of Seattle.[81] Additional shelters, parking lots, and encampment sites are operated by charity organizations and churches in the area;[82] during severe weather events such as heat waves and cold snaps, local governments open additional shelter spaces, but these often reach capacity.[83] In 2021, a total of $123 million was spent on homelessness services by local governments in King County, including cities and the regional authority.[81] The regional authority's five-year plan, released in 2023, estimates that $8 billion in capital costs would be required to build and staff 18,205 new units of temporary and transitional housing to address the homelessness crisis.[84]

The January 2023 point-in-time survey conducted in Pierce County identified 2,148 people who were experiencing homelessness, of whom 59 percent were in shelters and 21 percent were unsheltered—either outdoors or in vehicles.[85][86] The city of Tacoma has 1,225 shelter beds and 137 permanent housing units as of 2022[update]; the city government plans to temporarily increase shelter capacity while transitioning to more permanent and long-term housing for homeless people.[87] In Snohomish County, 1,285 homeless individuals in 1,028 households were identified in the January 2023 survey; of them, 594 were in shelters and 691 were unsheltered.[88] Approximately 1,500 students in the Everett School District, the county's largest school system, were identified as homeless in 2022.[89] The county has 683 year-round shelter beds and increases capacity during inclement weather; the county government purchased two former motels in 2022 to provide an additional 130 rooms.[90]

Economy

editThe region had a gross domestic product (GDP) of $517.8 billion in 2022, the eleventh-highest in the United States.[4] In the same year, the Seattle area also had a GDP per capita of $128,316, the third-highest figure among large metropolitan areas in the United States, behind San Jose and San Francisco.[91] As of November 2023[update], the largest employment sector is professional and business services, with approximately 401,200 employees, followed by trade, transportation, and utilities (369,100), education and health services (318,400), and government (276,700). A total of 2,181,500 jobs are available in non-farm sectors in the Seattle metropolitan area; the unemployment rate was 3.5% in November 2022 and 4.0% in November 2023.[92] The average weekly wage was $1,868 across the metropolitan area in mid-2023, compared to $1,332 nationally;[92] the region has some of the highest hourly minimum wages in the United States, ranging from the state minimum of $16.28 to $19.97 in Seattle for large employers and $20.29 in Tukwila as of 2024[update].[93]

Seattle is noted for its technology industry, which developed in the late 20th century and grew significantly with the development of Microsoft and Amazon.[94] The industry has 290,000 workers based in the Seattle area, ranking second nationally behind the San Francisco Bay Area, and comprises 13 percent of the regional workforce;[95][96] from 2005 to 2017, Seattle was one of five metropolitan areas that had 90 percent of the new technology jobs created in the United States.[97] Amazon is the largest private employer in the region, having grown from fewer than 5,000 local employees in 2009 to approximately 60,000 in 2020;[98] Microsoft, the second-largest tech employer in the region with 57,000 employees as of 2021[update],[99] has several subsidiary video game studios in the region. The Eastside is also home to game developers and distributors Valve, Bungie, and Nintendo of America.[100] Since the late 2000s, the area has also become home to satellite offices for Silicon Valley companies such as Google, Meta, and Salesforce.[101][102] Seattle has historically had few venture capital firms to invest in startups until the 2010s with the advent of new companies founded by alumni of older tech companies in the area;[103] in the early 2020s, several Seattle-area startups were labeled unicorns with a valuation of at least $1 billion.[104]

The region also has a large aerospace industry that is dominated by Boeing, historically the largest employer in Washington state with 60,244 workers as of 2022[update].[105] The company has major commercial jetliner assembly plants in Everett and Renton alongside testing facilities in Seattle and smaller component manufacturers in other areas.[106][107] The Boeing Everett Factory is the world's largest building by volume and is the assembly site of the 747, 767 and 777 programs, including their variants, alongside most 787s.[108] The company was headquartered in Seattle until its move to Chicago in 2001; in subsequent years, widebody production of the 787 was moved to Charleston, South Carolina.[107] The Seattle region is also home to several startup electric aircraft and component manufacturers, including Eviation and MagniX, who emerged in the 2010s.[109] The decade also saw the establishment of several space technology companies in the area, including Kent-based Blue Origin, Vulcan Aerospace, Kuiper Systems, and satellite offices for SpaceX;[110][111] the industry has 13,000 jobs in the Puget Sound region as of 2022[update], a two-fold increase since 2018.[111][112]

The region is a major hub for international trade and handles most of Washington's exports, which totaled $78 billion in 2018, through three major seaports on Puget Sound.[113] The Northwest Seaport Alliance was formed in 2015 to enable cooperation between the Port of Seattle and Port of Tacoma, rival public ports situated 32 miles (51 km) apart.[114] The two ports combine to form the seventh-largest container port in the United States and has the second-largest concentration of warehouse space on the West Coast.[115][116] The independent Port of Everett is a smaller port but handles exports of a similar value to Seattle and Tacoma due to its proximity to the Boeing Everett Factory.[117] Other maritime industries in the area include shipbuilding and commercial fishing,[32] particularly boat fleets based in Seattle that travel annually to the northern Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea near Alaska.[118][119]

The city has a major coffee retail industry that developed in the 1970s and 1980s and spawned several chains that remain headquartered in Seattle, including Starbucks and Tully's Coffee.[120] Seattle had the third-most coffee shops per capita in 2019 among U.S. cities, including independent shops and other roasters.[121] The city proper serves as the headquarters for other major companies in various industries, including online travel agency Expedia and wood producer Weyerhaeuser. National retailers REI and Nordstrom were also founded in Seattle and remain headquartered in the area.[113][122] Bellevue is home to the head offices of truck manufacturer Paccar, telecom network T-Mobile US, and clothing retailer Eddie Bauer.[123] Warehouse retailer Costco is headquartered in Issaquah and has more than a dozen locations in the Seattle area.[124] The region has several large shopping centers that range from traditional enclosed malls like Alderwood Mall and Westfield Southcenter to newer outdoor designs such as University Village.[125][126] While suburban areas have had few retail vacancies since the COVID-19 pandemic, Downtown Seattle has had a slower recovery with a vacancy rate of nearly 14 percent as of late 2023.[127][128] In the retail grocery sector, the most popular supermarket chains in the region are owned by Kroger (Fred Meyer and QFC) and the Albertsons Companies (Albertsons, Safeway), alongside warehouse retailers like Costco.[129]

Tourism

editThe Seattle area is a tourist destination, especially during the summer months, for domestic and international visitors. The metropolitan area's tourism industry employed 209,000 residents in early 2020, later reduced to 181,000 by 2022 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[130] In 2022, an estimated 33.9 million visitors in Seattle and King County spent $7.4 billion;[131] the region had reached a peak of 41.9 million visitors in 2019.[132] Pike Place Market in Downtown Seattle, a large public market with more than 220 shops and restaurants,[133] draws 10 million annual visitors and is among the most-visited tourist attractions in the world.[134] Other major attractions in Seattle include the Space Needle, the Seattle Center Monorail, Seattle Great Wheel, the Amazon Spheres, the Seattle Underground Tour, and the historic Pioneer Square neighborhood.[130][132] The city is also home to three cruise ship terminals operated by the Port of Seattle that serve excursions through the Inside Passage to Alaska.[135] An estimated 1.8 million passengers visited Seattle on 291 departures during the 2023 summer season with an estimated economic impact of $900 million.[136][137]

The region has several convention centers that are able to host large events, such as trade shows, fan conventions, corporate meetings, and conferences. The first portion of the Seattle Convention Center (formerly the Washington State Convention Center) was built over Interstate 5 and opened in 1988;[138] it expanded to a second building in 2023 to meet growing demand for event space in Downtown Seattle.[139] The convention center can hold simultaneous events and has over 1.5 million square feet (140,000 m2) of exhibition and meeting space.[140] Its largest annual events include PAX West (formerly the Penny Arcade Expo), Emerald City Comic Con, Sakura-Con, and the Northwest Flower and Garden Show, which each attract over 10,000 attendees.[141] Smaller convention centers in the area include the Meydenbauer Center in Bellevue, the Lynnwood Event Center, and the Greater Tacoma Convention and Trade Center.[142][143]

The areas outside of Seattle proper attract fewer tourists and draw largely from local and regional visitors. In Snohomish County, a majority of visitors in 2019 were from Western Washington and included a large number from within the metropolitan area.[144] Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the county's largest tourist attraction was the Future of Flight Aviation Center adjacent to Paine Field, which offered tours of the nearby Boeing Everett Factory and drew 300,000 annual visitors.[145] Pierce County had 8.8 million visitors in 2021 and estimated that they spent a total of $1.4 billion.[146] Mount Rainier National Park, located mostly in the county, had 2.3 million visitors in 2022—primarily between July and September.[147]

Government and politics

editThe Seattle MSA comprises three counties, nine federally recognized tribes, and 77 municipalities classified as cities or towns, each with their own governments.[148] These include 39 municipalities in King County, 23 in Pierce County, and 20 in Snohomish County; several cities also extend beyond the borders of a single county.[149] Approximately 71 percent of Puget Sound region residents live in an incorporated city or town; the rest are in unincorporated areas under the direct jurisdiction of counties, which act as the local government.[150][151] These developed unincorporated areas generally lie within the urban growth areas for existing cities that could annex them or in county-designated areas that would allow communities to vote for incorporation.[152][153] The incorporated city and town governments vary between mayor–council and council–manager systems, the latter using a council-appointed city manager to handle administration.[154]

All three counties have a home rule charter and are led by an elected county executive and a county council with members representing geographic districts.[155][156] The elections for the county executive and council, along with other major offices, are held in even-numbered years for Pierce County and odd-numbered years in King and Snohomish counties.[157][158] The county governments are responsible for various duties for all residents that are generally delegated to other elected and appointed officials, including the assessor, clerk, coroner and medical examiner, prosecuting attorney, and treasurer.[159] These duties include organization of elections and voter registration, enforcement of land use regulations, management of vital records, property assessment, tax collection, public health, and building inspections.[151][160] The counties also manage the criminal justice system, including the superior and district courts, public defenders, and jails.[161]

The Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC), the designated metropolitan planning organization for the Seattle MSA and Kitsap County, has voluntary membership from 82 municipalities, four tribes, four public ports, and six public transit operators.[150][162] It maintains a long-range plan for population growth, economic development, and regional transportation that is overseen by an executive board and general assembly of all members.[148][150] The organization also distributes state and federal funding for projects within the four-county area.[163] Other inter-county organizations include special districts and regional authorities for conservation, transit, libraries, and firefighting; as of 2007[update], there are over 220 special purpose districts in the Seattle metropolitan area.[149] Tax rates are set by local governments and can vary due to contributions to special districts; the combined sales tax ranges from 8.1% in parts of Pierce County to 10.6% in several Snohomish County cities, the highest rate in the state.[164][165]

The Seattle MSA is part of seven congressional districts (the 1st, 2nd, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th) that each elect a member of the United States House of Representatives.[166] The boundaries are redrawn every 10 years by the state's independent redistricting commission based on the results of the decennial census.[167] The 8th district is the only one to span all three counties, taking the rural eastern portions and including areas east of the Cascade Mountains.[168] According to the 2022 Cook Partisan Voting Index, six of the congressional districts lean towards Democratic candidates while the 8th district is even between both major parties.[169] In the state legislature, the metropolitan area is part of 28 districts that each elect two House members to a two-year term and one senator to a four-year term.[170][171] By the 2021 session, almost all legislative districts in the region were represented solely by Democrats in the Senate and House, with the exception of exurban districts.[172] According to a 2022 marketing survey by Nielsen, the Seattle metropolitan area is tied for the eighth highest percentage of adults who favored the Democratic Party, at nearly 55 percent—an 11-point increase from a similar survey conducted in 2004.[173] The area also decides most statewide elections due to their large population, which has contributed to an unbroken line of Democratic governors since 1984.[174]

Education

editPublic K–12 education is managed by local school districts that are governed by elected boards and overseen by two of the state's nine regional educational service districts.[175] The Puget Sound Educational Service District covers 35 school districts and 416,000 students in King and Pierce counties, along with Bainbridge Island in Kitsap County, and includes 40 percent of the state's student population.[176] The Northwest Educational Service District encompasses 35 school districts in northwestern Washington, including all 14 in Snohomish County.[177] The public school districts are primarily funded by allocations from the state government and local property tax levies that are approved by voters.[175][178]

The largest school district in the metropolitan area is Seattle Public Schools, which has 51,000 students enrolled for the 2023–24 school year, a 9 percent decrease from its 2019 peak of 56,000 students.[179] The district has 106 schools and over 6,000 staff members;[180][181] most students attend their closest neighborhood schools, while option schools are able to enroll students from across the city.[181] Other large districts with more than 20,000 enrolled students include Lake Washington, Tacoma, Kent, Northshore, Puyallup, and Federal Way.[182] According to the U.S. News & World Report, the top high schools in the metropolitan area are primarily in the Eastside region, along with specialized industry and technical schools in Tukwila and Lakewood; the highest-ranked school in Washington is the Tesla STEM High School in the Lake Washington School District.[183] The smallest school district in the Seattle area is the Index School District, which has 19 students and no high school.[184]

The Seattle area has hundreds of registered private schools that serve over 50,000 students and offer alternative curriculums or religious education.[185][186][187] The largest private schools in the area are Cedar Park Christian School and King's Schools, both Christian programs.[188] Since a state referendum in 2012, charter schools have been approved to operate in the area using using public funding while remaining privately-run.[189] These non-district schools are also overseen by the educational service district of their respective region;[190] they are also allowed to participate in the same athletics competitions as public schools under the management of the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association.[185]

Higher education

editThe Seattle area has several universities and colleges that provide post-secondary education and are run by public or private institutions.[191] According to the National Center for Education Statistics, approximately 45 percent of people in the Seattle–Tacoma–Olympia combined statistical area in 2019 had a bachelor's degree or higher—the tenth-highest rate in the United States.[192] This includes a high number of out-of-state adults who reside in the metropolitan area; according to a 2015 Brookings Institution study, 48% of out-of-state adults had a bachelor's degree or higher compared to 35% of in-state adults.[193]

The oldest and largest public university in the state is University of Washington (UW), which was founded in 1861 and has over 60,000 total students in nearly 500 programs at its three campuses.[194] The 342-acre (138 ha) main campus in Seattle was established in 1895 after moving from Downtown Seattle;[195] it was joined in 1990 by branch institutions in Bothell and Tacoma that later built permanent campuses in the late 1990s and early 2000s.[196][197] UW is also a major research university with an annual budget of $10.4 billion and one of the largest employers in the metropolitan area.[194][198] The state's second-largest institution, Washington State University, has an Everett branch campus that was established in 2011 after plans for a UW branch campus were shelved amid the Great Recession.[199]

The area has 17 community colleges and technical colleges that offer two-year degrees and other programs, including transfers to local four-year universities.[200][201] Each college is assigned a specific district that also conforms to county boundaries.[200][202] As of 2023[update], the largest community college in the state is Bellevue College, which has nearly 9,000 full-time students; other colleges with more than 5,000 enrolled students include Pierce College, Green River College, and Highline College.[203] The three community colleges in Seattle proper form the Seattle Colleges District, which has over 12,000 total students as of 2021[update].[204] The area also has several private four-year and two-year institutions that focus on religious or liberal arts programs. These include Seattle University, Seattle Pacific University, Pacific Lutheran University, and University of Puget Sound.[205]

Media

editThe Seattle–Tacoma Designated Market Area, as defined by Nielsen Media Research, includes most of Western Washington and the Wenatchee metropolitan area.[206] As of 2021[update], it is the 12th largest television market[207] and 11th largest radio market in the United States by population.[208] King County has the majority of the region's television and radio antenna towers, which are concentrated on Seattle's hills or on Cougar Mountain and Tiger Mountain in the Issaquah Alps.[209][210][211] In addition to over-the-air television, the region is also served by cable and satellite providers, the largest of which is Comcast Xfinity and Wave Broadband.[212]

All major national television networks have affiliates in the region who also produce local news broadcasts and other programming;[213] these include KOMO 4 (ABC), KING 5 (NBC), KIRO 7 (CBS), and KCPQ 13 (Fox).[214][215] The Seattle area has two non-profit stations that are members of PBS, the U.S. national public broadcaster: KCTS in Seattle and KBTC in Tacoma.[216] The region's largest Spanish-language television station, KUNS, lost its Univision affiliation in 2023 and was replaced by Bellingham-based KVOS, which did not produce local news content.[217] National news television network MSNBC was launched jointly by Microsoft and NBC in 1996; its online news operations were based in Redmond until 2012.[218]

The largest radio stations in the Seattle area by listenership are primarily music stations, including several owned by national network iHeart Radio, and talk stations with local ownership.[219][220] The first radio broadcasters in Seattle emerged in 1922, including the still-operating KJR, and grew through the decade; several radio broadcasters later established their own television stations following the first local broadcast in Seattle by KING predecessor KRSC-TV in 1948.[221][222] Among the most popular modern stations is KEXP-FM, a non-profit music station that has a worldwide following due to its early use of internet broadcasting.[223] The Seattle area has two NPR-affiliated public radio stations: KUOW-FM, founded at the University of Washington in 1952;[221] and KNKX-FM, founded at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma as KPLU. An attempted takeover of KPLU by KUOW in 2016 resulted in public outcry and the establishment of KNKX under independent ownership.[224]

The region has three major newspapers based in the largest cities of each county: The Seattle Times, the most-circulated newspaper in the Pacific Northwest, is a daily newspaper based in Seattle and had over 75,000 subscribers in 2022;[225] The News Tribune in Tacoma has approximately 54,000 subscribers and switched to a three-day publication schedule in 2024;[226] and The Daily Herald in Everett has 33,500 subscribers as of 2022[update] and prints six editions a week.[227][228] Seattle's oldest daily newspaper, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, ceased print publication in 2009 and became an online-only outlet.[229][230] The Seattle area also has weekly newspapers in smaller cities, including several owned by Sound Publishing or independent companies;[231][232] other hyperlocal publications, primarily in Seattle neighborhoods, have largely ceased publication in the early 21st century.[233]

Other newspapers include free weeklies The Stranger and Seattle Weekly, which both ceased regular print publication by 2020;[231][234] trade and industry publications Puget Sound Business Journal and Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce;[230][235] and student newspaper The Daily of the University of Washington.[230] The region also has publications in English and other languages for ethnic communities. These include Asian-American publications International Examiner, Northwest Asian Weekly, and the Seattle Chinese Post;[236] and the Seattle Medium and The Facts, both catered towards the Black community.[237] Real Change, a weekly street newspaper, has been published since 1994 and is sold by homeless and low-income vendors with an estimated annual circulation of 550,000 copies.[238] Several digital-only publications emerged in the 2000s and 2010s to provide local news, including Crosscut.com, tech industry publication GeekWire, and hyperlocal outlets Capitol Hill Seattle Blog and West Seattle Blog.[239]

Libraries

editThe Seattle metropolitan area has several local public library systems that are funded primarily by property taxes that are set by voter-approved levies within a designated library district.[240] These include library districts that cover most of a county—either through direct annexation or contracted by local governments—or a department of the city government.[241][242] Some cities have opted out of having library systems after voters rejected the proposed property tax to fund services.[242] The earliest public libraries in the region were established in the late 19th century by private organizations that were later absorbed into city governments; the first was in Steilacoom in 1858 and was followed by a Seattle organization in 1868.[243] Several city libraries and local branches were constructed across the metropolitan area with grants from industrialist Andrew Carnegie beginning in 1901.[244] In addition to public libraries, the region also has informal public bookcases (part of the Little Free Library movement) and neighborhood tool libraries that lend tools and materials.[245][246]

The King County Library System is the largest library in the region, with 50 branches and a total circulation of nearly 18.9 million physical and digital items as of 2022[update].[247][248] It was established as a rural library district in 1943 and absorbed most of the city-operated systems in King County, with the exception of the Seattle Public Library, by 2012.[249] The independent Seattle system has 27 locations, including its Central Library in Downtown Seattle, and had a 2022 circulation of 11 million items.[248][250] The Sno-Isle Libraries system serves most of Snohomish and Island counties and has 23 locations that circulated 7.4 million items in 2022;[248] Sno-Isle does not serve the city of Everett, which operates the two locations of the Everett Public Library.[251] Pierce County has a county library system with 20 locations that circulated 4.8 million items in 2022 and separate, city-run libraries in Tacoma with eight locations and Puyallup with one location.[248] In 2016, the King County, Sno-Isle, and Seattle systems were among the three largest libraries in the United States by circulation.[252] The King County and Seattle systems were also among the heaviest users of digital lending platform OverDrive by circulation worldwide in 2023, each with more than 5 million checkouts.[253]

Healthcare

editThe metropolitan area has 23 hospitals that provide emergency or specialized medical care and are operated by public authorities or private organizations.[254][255] Non-profit Catholic organization Providence Health & Services and its subsidiary Swedish Health Services[256] are the largest operator of regional hospitals with seven facilities and over 2,100 combined licensed beds in King and Snohomish counties.[257][258] The UW Medicine system, managed by the University of Washington, comprises several of the largest hospitals in Seattle and a regional network of clinics.[259][260] Among them is Harborview Medical Center on First Hill, a 413-bed public hospital and the only Level I trauma center in the state.[261][262] Other major healthcare systems in the Seattle area include EvergreenHealth, MultiCare, Overlake Hospital Medical Center, and Virginia Mason Franciscan Health.[257][263]

The Seattle area also has specialized medical facilities that serve the Pacific Northwest or wider regions of the United States. Seattle Children's Hospital is a major pediatric hospital that serves Washington and four other states;[264] the area has several hospitals for military members and veterans in the area, including the Madigan Army Medical Center on Joint Base Lewis–McChord and the Department of Veterans Affairs' Puget Sound Health Care System.[265][266] The largest psychiatric hospital in the region is Western State Hospital in Lakewood, which has a capacity of 800 residents; the three-county region has a total of 64 beds at government facilities and is also home to several private behavioral health centers run by Universal Health Services.[267][268]

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that about 5.7 percent of annual spending for residents in the Seattle metropolitan area was on healthcare.[269] According to a 2022 estimate by the United States Census Bureau, approximately 5.3 percent of people in the Seattle metropolitan area lack health insurance.[270] As of 2021[update], the largest insurer in the region is Mountlake Terrace-based Premera Blue Cross, followed by Cambia Health Solutions and Kaiser Permanente.[271] Nearly 900,000 people in the tri-county region are enrolled in Washington Apple Health, a no-cost health insurance program managed by the state government under the federal Medicaid system.[272] An additional 533,000 people in the area were enrolled in Medicare in 2018.[273]

The region has several local health departments that set and enforce public health regulations and perform other duties to prevent the spread of disease:[274] Public Health – Seattle & King County, the Snohomish County Health Department, and Tacoma–Pierce County Health Department are dedicated departments within their respective county governments.[275] In January 2020, the Seattle area detected the first known case of COVID-19 in the United States and within two months had the first deaths from the pandemic in the country; the region's relatively low death rate was credited to actions taken by public health authorities and the use of extensive testing and widespread remote work policies before the rest of the country adopted them.[276][277] Seattle is also home to several major health research institutions, including the Center for Global Infectious Disease Research, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Gates Foundation, PATH, and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.[278][279]

Transportation

editAirports

editThe largest airport in the region is Seattle–Tacoma International Airport in SeaTac, a major international airport that serves as a commercial hub for Alaska Airlines and Delta Air Lines.[280] It is operated by the Port of Seattle and lies between Seattle and Tacoma; both cities contributed financially to its construction, which was completed in 1944 for military use and later expanded for commercial aviation.[281] Sea-Tac served 46 million passengers in 2023 and was the 11th busiest airport in the United States and 28th busiest in the world by passenger volume.[282] As of 2023[update], the airport has 91 domestic destinations and 28 international destinations in North America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania.[283][284]

The area's other conventional passenger airport is Paine Field in Everett, 30 miles (48 km) north of Downtown Seattle. The airport is owned by the Snohomish County government and primarily used for general aviation and various industries, including the nearby Boeing Everett Factory. The passenger terminal, operated by a private company, opened in 2019 and serves domestic destinations, primarily in the Western United States.[285] As of 2023[update], Alaska Airlines is the sole airline at Paine Field and serves up to eleven destinations during peak seasons.[283]

Proposals to build a reliever airport for Sea-Tac were investigated in the 1990s prior to the decision to build a third runway at the airport to handle increased traffic.[286] The state legislature convened a new commission in 2019 to search for a suitable site for a reliever airport, which could include expansion of Paine Field or construction of an outlying airport by 2040.[287] The commission identified four sites in the southern Puget Sound region but was dissolved before a final recommendation due to public opposition to a new airport.[288]

Limited passenger service is also available from Boeing Field in Seattle, which primarily serves cargo and charter traffic.[284][289] Kenmore Air, a passenger floatplane operator, serves two airports in the area: the Kenmore Air Harbor Seaplane Base on Lake Union in Seattle and Kenmore Air Harbor on Lake Washington in Kenmore.[290] The metropolitan area's other general-use airports include Arlington Municipal Airport in northern Snohomish County;[291] Bremerton National Airport in Kitsap County;[292] the privately-owned Harvey Airfield in Snohomish;[293] and Renton Municipal Airport, adjacent to Lake Washington and the Boeing Renton Factory.[294]

Roads and highways

editThe Seattle area has a grid-based road system that originates at designated points in each of the three counties; streets and roads are numbered from this origin point with cardinal directions as prefixes or suffixes.[295] The origin for the King County grid is 1st Avenue and Main Street in Downtown Seattle; from there, numbers increase outward until they reach the county border and reset.[295][296] The northernmost street in King County is Northeast 205th Street, which runs along the county line and is known as 244th Street Southwest in Snohomish County.[297][298] Cities are permitted to have separate numbering and naming systems for streets,[295] including retaining older names prior to the harmonization of street numbers following the adoption of a countywide 911 system in the late 20th century.[299][300]

In addition to streets and roads under the jurisdiction of the local and county governments, the state legislature designates a network of state highways that are maintained by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT).[301][302] These highways are primarily funded by the state government through a fuel tax and annual fees on vehicle registration that are collected by other departments.[303][304] Several highways connect beyond the Puget Sound region, including crossings of the Cascade Mountains through mountain passes—of which three have winter access during normal weather.[305] Some city streets in the state highway system, such as Aurora Avenue North on State Route 99 (SR 99), have shared jurisdiction or ownership between WSDOT and local governments.[306][307]

The state highway system comprises undivided highways as well as controlled-access freeways,[308] which include several routes on the national Interstate Highway System that cover a total of 182 miles (293 km) in the Seattle metropolitan area.[309][310] These freeways were built by the state government in the 20th century to conform with standards set by the Federal Highway Administration and are numbered as part of a national scheme.[311][312] The main West Coast freeway, Interstate 5 (I-5), travels through the region and serves the cities of Tacoma, Seattle, and Everett; its busiest section in Downtown Seattle carried 274,000 vehicles on an average day in 2016, while approximately 2.6 billion person miles were traveled on the corridor between Federal Way and Everett in 2017.[313][314] The only east–west Interstate in the area is I-90, which connects Seattle to Bellevue, Issaquah, and Eastern Washington via Snoqualmie Pass.[305] I-5 has two auxiliary routes in the region: I-405, which serves the Eastside and functions as a bypass of Seattle;[315] and I-705, a short spur into Downtown Tacoma that opened in 1990.[316]

Other major freeways in the area include SR 16 from Tacoma to the Kitsap Peninsula; SR 18 from Federal Way to Snoqualmie; SR 167 from Puyallup to Renton; SR 509 from SeaTac to Seattle; SR 520 from Seattle to Redmond; SR 522 from Bothell to Monroe; and U.S. Route 2 (US 2) from Everett to Snohomish.[308][317] Plans for a larger network of freeways and expressways were drawn up in the 1950s and 1960s, but were later cancelled or downsized due to public outcry and budget issues. Among the cancelled projects were the R.H. Thomson Expressway in eastern Seattle, the Bay Freeway in Seattle's South Lake Union neighborhood, and an outer bypass of the Eastside unofficially named Interstate 605 that was proposed several times.[318] The highway system includes several of the longest floating bridges in the world due to the depth of local water bodies and their soft silt, which make conventional bridge designs more challenging.[319] Lake Washington has three of the bridges: a pair carries separate directions of I-90, while the Evergreen Point Floating Bridge carries SR 520 and is the world's longest floating bridge at 7,700 feet (2,300 m).[319][320] The SR 520 floating bridge is one of two toll bridges in the area, along with the eastbound span of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge on SR 16, which was constructed with toll revenue.[321] The toll bridges and the State Route 99 tunnel in Seattle use the Good to Go electronic toll system, which charges based on a transponder or by reading a vehicle's license plate with fees collected by mail.[322]

The region's freeway system includes a network of high-occupancy vehicle lanes (HOV lanes) to encourage use of mass transit and carpools during peak periods;[323] the lanes also include bypasses at ramp meters and special ramps at some interchanges.[324][325] As of 2018[update], 250 miles (400 km) of the planned 369 miles (594 km) in the network have been constructed and carry 38 percent of all freeway miles traveled.[313] it was the third-largest system of HOV lanes among U.S. metropolitan areas in 2008.[326] A 40-mile (64 km) section of HOV lanes on I-405 and SR 167 are planned to be converted to high-occupancy toll lanes (HOT lanes) by the late 2020s.[327] The Good to Go system is used to collect tolls for single-occupant vehicles in the lanes and are set by variable demand with a maximum of $15; vehicles carrying three or more people are exempt from the toll with a compatible transponder.[328]

Railroads

editThe region is served by two Class I railroads primarily used for freight: BNSF Railway, which owns several lines that connect the north–south I-5 corridor and across the Cascade Mountains; and the Union Pacific Railroad, which owns a short section from Tukwila to Tacoma and has operating rights on other BNSF lines.[329] Amtrak operates intercity passenger trains on these railroads with stations in the Seattle metropolitan area. The Cascades serves the Portland–Seattle–Vancouver corridor with multiple trips per day; the Coast Starlight operates daily service to Oregon and California from King Street Station in Seattle; and the Empire Builder connects the region to Eastern Washington and Chicago.[329] The Cascades travels along the Pacific Northwest Corridor, a designated study corridor for potential high-speed rail service.[329][330]

Mass transit

editThe Seattle metropolitan area has seven major transit agencies that provide public transportation across several modes, including buses, light rail, commuter rail, and ferries. Most transit modes in the region use the ORCA card, a smart fare card system introduced in 2009.[331][332] Fares are discounted for people aged 65 or older or those with disabilities; since 2022, all fares for passengers 18 years old and younger have been waived as part of a state program.[333] According to 2019 estimates from the American Community Survey, approximately 10.7 percent of workers in the Seattle metropolitan area used public transit to commute—the sixth most per capita among the largest metropolitan areas in the United States.[334] The high ridership, particularly for buses in the 2010s, was attributed to subsidized fares and other benefits offered by large employers for commuters.[335]

Sound Transit is a regional authority that manages Link light rail, Sounder commuter rail, and Sound Transit Express buses on freeways.[336] It was created in 1993 and has a district that covers 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2) and 2.9 million people across 50 municipalities.[337] Link, the regional rapid transit system, carried 23.9 million passengers in 2022 on its two lines: the 1 Line from Seattle to SeaTac, and the T Line in Tacoma.[336][338] Sound Transit's major capital projects are funded by several sources, including property taxes and fees on motor-vehicle registrations, that are enabled by ballot initiatives approved by voters in 1996, 2008, and 2016.[337][339] The light rail system plans to expand to 116 miles (187 km) by 2045 and cover several major corridors at a total cost of $149 billion.[339] Other local rail systems include the Seattle Streetcar network, which comprises two lines,[340] and the Seattle Center Monorail, a popular tourist attraction that carries 2 million riders annually.[341]

The largest local transit agency is King County Metro, which operates buses, paratransit, vanpools, and rideshare in King County. It also operates an electric trolleybus network in Seattle as well as the city's streetcar system.[342] Metro is one of the largest bus agencies in the United States by ridership, carrying 63.6 million annual passengers in 2022.[338] Snohomish County has two transit providers: Community Transit, which serves most of the county and also operates commuter express service to Seattle; and Everett Transit, which serves the city.[343] Other providers include Pierce Transit in Tacoma and Pierce County; Kitsap Transit in Kitsap County;[344] and Intercity Transit in Olympia and Thurston County, which operates fare-free.[345]

Ferries

editThe state-run Washington State Ferries system is the largest maritime transit system in the United States and carries both passengers and vehicles as an extension of the state highway system; it also serves as a tourist attraction in addition to its role as a commuter mode.[346][347] The ferries carried 17.4 million passengers and 8.6 million vehicles in 2022; prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and service cuts, it had carried 25 million annual passengers.[348][349] The system was created in 1951 after a state takeover of the Puget Sound Navigation Company's main lines in the region.[346] Colman Dock in Downtown Seattle is the system's main hub and is served by routes from Bainbridge Island and Bremerton.[350] Vashon Island has two terminals at opposite ends of the island: the north terminal is used by the Southworth–Vashon–Fauntleroy triangle service that connects east to West Seattle; and the south terminal at Tahlequah is part of the Point Defiance–Tahlequah route from Tacoma.[351] Two routes serve Snohomish County: the Edmonds–Kingston run connects to the Kitsap Peninsula and the Mukilteo–Clinton run travels to Whidbey Island.[352] The Pierce County government operates the Steilacoom–Anderson Island ferry with automobile service to two island communities in southern Puget Sound.[353]

The King County Marine Division operates the King County Water Taxi, a passenger ferry service that connects Downtown Seattle to West Seattle and Vashon Island.[354] The Vashon Island run was formerly a passenger ferry operated by Washington State Ferries from 1990 until 2006, when the state government cut its funding; the county government later acquired the service under a new ferry district.[355] The passenger-only Kitsap Fast Ferries system operated by Kitsap Transit connects a terminal near Colman Dock to three terminals on the Kitsap Peninsula.[356] Kitsap Transit launched the system's first route, Seattle–Bremerton, in 2017 to provide a faster alternative to the existing state ferry run; it expanded using a fleet of catamarans designed for low wakes.[357] The agency also runs a passenger-only foot ferry between Bremerton and two terminals in Port Orchard using the historic Carlisle II and other boats.[358][359] The Port of Everett runs a seasonal passenger ferry between Everett and Jetty Island in Possession Sound.[360] These services are similar to that of the historic Mosquito Fleet, a collective name for passenger ferries operated on Puget Sound from the 1880s to 1920s.[361]

In addition to public operators, several private ferry and excursion services are based in the Seattle area. The Victoria Clipper connects Downtown Seattle to Victoria, British Columbia, via an international passenger ferry.[362] Argosy Cruises operates sightseeing cruises in Elliott Bay and the Lake Washington Ship Canal; from 2009 to 2021, the company also operated Tillicum Village, a performance and culinary cruise on Blake Island.[363]

Utilities

editThere are six electric utilities that distribute electricity to customers in a local market within the Seattle metropolitan area.[364] They draw most of their electric power from hydroelectric dams in the Pacific Northwest, along with wind, natural gas, and coal.[365][366] In 2020, these utilities generated or sold over 43,019,000 megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity, of which 52 percent was from hydroelectric sources.[367] The largest utility, Puget Sound Energy, is a private company that covers most of King County and portions of Pierce County; as of 2022[update], it derives half of its electricity from coal and natural gas.[365][368] The company is one of two non-government providers alongside the Peninsula Light Company, a non-profit cooperative on the Key Peninsula.[364][369] The remaining local providers, Seattle City Light, the Snohomish County Public Utility District, and Tacoma Power, are public utilities who are also members of the Energy Northwest consortium.[370] They generate their own electricity and also purchase it from the federal Bonneville Power Administration, which operates 31 hydroelectric dams on the Columbia and Snake rivers.[371] The cost of electricity in the metropolitan area is approximately 25 percent below the average for the United States due to its reliance on hydroelectricity;[372] as of 2019[update], the average price of electricity ranged from 7.9 cents per kilowatt-hour in Tacoma to 10.2 cents for Puget Sound Energy customers.[373]

The region derives most of its tap water from sources in the Cascade Mountains that are fed by melted snowpack that accumulate during the autumn and winter and fill reservoirs as they melt.[374] The water is collected and treated by three major public utilities that distribute it for consumption: the City of Everett manages the water supply for most of Snohomish County, which is derived from Spada Lake on the Sultan River; Seattle Public Utilities serves 1.3 million people in King County and has two major water sources on the Cedar and Tolt rivers;[375] and Tacoma Public Utilities uses the upper Green River in King County to serve Pierce County and portions of southern King County.[364]: 7.6 [376] The utilities and other providers also rely on groundwater wells that draw from a series of underground aquifers in the region, but their use has diminished since the mid-20th century.[364]: 6.7 [377] The treatment process generally includes the addition of water fluoridation and the use of chlorine as well as ozone or ultraviolet light disinfection.[378][379]

Wastewater is collected locally and sent through sewers and pump stations to regional treatment facilities to be discharged into local waterways, primarily Puget Sound.[364]: 7.4 [380] The combined sewer system in older areas, including most of Seattle, also carries untreated stormwater that is dumped with wastewater during overflow events;[381] cities and utilities have undertaken projects to build separate stormwater tunnels and holding tanks to address the issue.[382] Solid waste is collected from curbside bins and dumpsters by local governments or contracted out to companies including Waste Management, Allied Waste, Republic Services, and Recology.[383][384] County and city governments also operate collection and distribution sites to sort waste before it is sent to a regional landfill or by rail to a waste-to-energy plant.[385][386] The curbside collection service also includes recycling pickup, which Seattle began in 1988,[387] which is sorted and processed locally and overseas.[388] In 2015, it became mandatory for providers to offer curbside collection of food waste for composting in Seattle after the program was expanded from commercial establishments to all households.[389] Various cities in the metropolitan area banned single-use plastic bags and began imposing charges on reusable or paper bags from 2009 onward,[390] ahead of a statewide ban that took effect in 2021.[391]

Residential and commercial central heating systems in the metropolitan area are primarily supplied by electricity or natural gas; some denser neighborhoods in Seattle also use steam district heating.[392][393] Puget Sound Energy provides natural gas to approximately 850,000 residents in the three metropolitan counties but has announced plans to transition to electric heating under new state regulations.[368][394] Natural gas, primarily sourced from Canada and states in the Rocky Mountains,[395] and petroleum are transported through a series of pipelines that travel along the Interstate 5 corridor in Western Washington.[396] The region is also served by oil refineries that primarily receive crude oil from Alaska via ship and from North Dakota via freight trains that pass through the Seattle area.[397] The local refineries produce gasoline and diesel fuel that is primarily used for transportation; prices for gasoline in the Seattle metropolitan area are among the highest in the United States, averaging 45 cents higher than the national average from 2017 to 2021, due to a more limited wholesale market.[398] The region historically had the lowest number of households using air conditioning in their homes in the U.S. due to the temperate summer climate. A series of major heat waves in the late 2010s and 2020s contributed to an increase in the number of households with air conditioning from 31 percent to over 53 percent by 2021.[399][400]

The Seattle metropolitan area has several broadband and fiber-optic internet service providers, including CenturyLink, Charter Spectrum, Comcast Xfinity, Wave Broadband, and Ziply Fiber;[401][402] approximately 85 percent of households in the metropolitan area had access to broadband internet service in 2014.[403] Comcast Xfinity has the largest market coverage in the area at an estimated 95 percent of households in 2015 and little overlap with competitors.[404] The Seattle area is also served by the three major cellular network companies in the U.S., including Bellevue-based T-Mobile US, and has had 5G coverage since the late 2010s.[405][406] The region is part of five area codes under the North American Numbering Plan: 206 in Seattle; 253 in Tacoma and the southern Puget Sound region; 360 for most of Western Washington; 425 in the Eastside and southern Snohomish County; and 564 as an overlay for the region introduced in 2017.[407] Area code 206 was originally assigned to all of Western Washington until it was split in the 1990s with the introduction of new local area codes.[408]

References

edit- ^ a b "2020 Gazetteer Files: Core Based Statistical Areas". United States Census Bureau. October 28, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "DP1: Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics". United States Census Bureau. August 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2020–2023". United States Census Bureau. March 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ a b "Total Gross Domestic Product for Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA (MSA)". Federal Reserve Economic Data. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. December 18, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "3-Digit ZIP Code Prefix Matrix". United States Postal Service. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "List 1: FIPS Metropolitan Area (CBSA) Codes" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2015. p. 6. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Population Division (April 2020). Washington: 2020 Core Based Statistical Areas and Counties (PDF) (Map). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "OMB Bulletin No. 23-01: Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. July 21, 2023. pp. 72, 81, 144. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Seattle–Tacoma, WA Combined Statistical Area (PDF) (Map). United States Census Bureau. February 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Puget Sound". Washington State Department of Ecology. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Gardner, Todd (February 2021). Changes in Metropolitan Area Definition, 1910–2010 (PDF). Center for Economic Studies (Report). United States Census Bureau. p. 6. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Population of Metropolitan Districts". Abstract of the Thirteenth Census, 1910 (PDF) (Report). United States Census Bureau. 1913. pp. 61–62. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Districts" (PDF). Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930 (Report). United States Census Bureau. 1932. p. 214. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Population in Greater City Area Mounts". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. August 30, 1931. p. 11.

- ^ Hoffman, Fergus (November 11, 1949). "Census Of Greater Seattle To Include All King County". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. 1.

- ^ "Portland Area Enlarged 12-Fold For 1950 Census". The Seattle Times. October 6, 1949. p. 10.

- ^ Fussell, E. B. (May 8, 1959). "Seattle Wins Point in Area Designation". The Seattle Times. p. 17.

- ^ "County Included in Seattle Metro Area". The Everett Herald. May 8, 1959. p. 6. Retrieved January 26, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Metropolitan Plan Stymied". The Everett Herald. March 6, 1958. p. 35. Retrieved January 26, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Spaeth, John D. (October 18, 1959). "Questions on Loans, Construction Answered". The Seattle Times. p. 38.

- ^ McDaniel, Robert (October 2, 1974). "Tacoma leaders sure city can snap out of slump". The Seattle Times. United Press International. p. B9.

- ^ Coughlin, Dan (April 19, 1964). "Paper Noose—Strangling Puget Sound Area". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. 1.

- ^ "Standard Consolidated Statistical Areas (SCSAs), 1981 with Codes". United States Census Bureau. November 18, 1999. Archived from the original on December 9, 2004. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Areas and Components, 1983 with FIPS Codes". United States Census Bureau. November 1998. Archived from the original on December 9, 2004. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Bremerton leads population gain in state's cities". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. March 19, 1993. p. B3.

- ^ "Census breaks down state population". The Olympian. Associated Press. March 18, 1993. p. A2. Retrieved January 26, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "OMB Bulletin No. 03-04 Attachment: Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, Combined Statistical Areas, New England City and Town Areas, Combined New England City and Town Areas" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. July 7, 2003. pp. 48, 102. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 9, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Washington – Core Based Statistical Areas and Counites (PDF) (Map). United States Census Bureau. June 2003. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "OMB Designates 49 New Metropolitan Statistical Areas" (PDF) (Press release). Office of Management and Budget. June 6, 2003. Retrieved January 26, 2024 – via National Archives and Records Administration.

- ^ "OMB Bulletin No. 07-01: Update of Statistical Area Definitions and Guidance on Their Uses" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. December 18, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "OMB Bulletin No. 13-01: Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. February 28, 2013. p. 109. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Regional Economic Strategy (Report). Puget Sound Regional Council. December 2021. pp. 10–12, 21–27. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Geranios, Nicholas K. (May 12, 2018). "Concerned About West Coast Volcanoes? Scientists Answer Burning Questions". KQED. Associated Press. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Landers, Rich (October 2, 2014). "In brief: U.S. Geological Survey takes a closer look at Glacier Peak eruption potential". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Norberg, David (October 13, 2020). "Mount Rainier National Park". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Coastal Habitats in Puget Sound". United States Geological Survey. June 3, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Washington City and Town Profiles". Municipal Research and Services Center. 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "Tribes". Puget Sound Regional Council. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Breda, Isabella (May 31, 2022). "Duwamish recognition fight underscores plight of treaty tribes". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Kapralos, Krista J. (August 22, 2008). "Tribal members, non-Indians live in the shadow of luxury". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Office of Local Defense Community Cooperation; Federal Research Division (October 2023). Defense Spending by State, Fiscal Year 2022 (PDF) (Report). United States Department of Defense. pp. 112–113, 126. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ "State Fact Sheets: Washington" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Ashton, Adam (July 16, 2015). "JBLM retains combat brigades, but loses 4 smaller units". The News Tribune. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Talton, Jon (September 26, 2014). "Military is big business in state, but at what cost?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Malone, Patrick (March 12, 2022). "What Russia's nuclear escalation means for Washington, with world's third-largest atomic arsenal". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Rivera, Ray (September 30, 2001). "State's huge military presence gains visibility with mobilization". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Reicher, Mike (May 22, 2021). "Thousands of military and veterans' COVID-19 vaccinations aren't in Washington state data, hindering pandemic response". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Balk, Gene (July 2, 2021). "What exodus? Seattle and Washington kept growing during pandemic; see how each county fared". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Gutman, David; Shapiro, Nina (August 12, 2021). "Seattle grew by more than 100,000 people in past 10 years, King County population booms, diversifies, new census data shows". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Frey, William H. (April 21, 2022). "A 2020 Census Portrait of America's Largest Metro Areas: Population growth, diversity, segregation, and youth" (PDF). Brookings Institution. pp. 10–14. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Saldanha, Alison (October 3, 2023). "How WA's Asian demographics have changed dramatically". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "One in six residents don't identify as straight or heterosexual". Puget Sound Regional Council. June 27, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Balk, Gene (December 9, 2022). "WA among top 10 states with highest concentration of same-sex couples". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Forecasting & Research Division (September 2023). State of Washington 2023 Population Trends (PDF) (Report). Washington State Office of Financial Management. pp. 12–13, 15–16. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Sillman, Marcie; O'Connell, Kate (May 26, 2015). "Don't Believe In God? Move To Seattle". KUOW. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Balk, Gene (February 29, 2024). "Seattle is the least-religious large metro area in the U.S." The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Religious Landscape Study: Adults in the Seattle metropolitan area". Religion & Public Life Project. Pew Research Center. November 3, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2015.