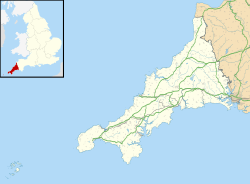

Restormel Castle (Cornish: Kastel Rostorrmel)[1] lies by the River Fowey near Lostwithiel in Cornwall, England, UK. It is one of the four chief Norman castles of Cornwall, the others being Launceston, Tintagel and Trematon. The castle is notable for its perfectly circular design. Once a luxurious residence of the Earl of Cornwall, the castle was all but ruined by the 16th century. It was briefly reoccupied and fought over during the English Civil War, but was subsequently abandoned. It is now in the care of English Heritage and open to the public.

| Restormel Castle | |

|---|---|

| Lostwithiel, Cornwall | |

Restormel Castle, seen from the west | |

| Coordinates | 50°25′20″N 4°40′17″W / 50.4223°N 4.6715°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference SX1032561466 |

| Type | Shell keep with bailey |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Controlled by | English Heritage |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Shale |

Architecture

editLocated on a spur overlooking the River Fowey, Restormel Castle is an unusually well-preserved example of a circular shell keep, a rare type of fortification built during a short period in the 12th and early 13th centuries. 71 examples are known in England and Wales, of which Restormel Castle is the most intact. Such castles were built by converting a wooden motte-and-bailey castle, the external palisade replaced by a stone wall and the internal bailey filled with domestic stone buildings. These were clustered around the inside of the wall to provide a defence. The buildings are curved to fit into the shell keep, in an extreme example of the 13th-century trend.[2][3]

The wall measures 38 metres (125 ft) in diameter and is up to 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) thick. It still stands to its full height with a wall walk 7.6 metres (25 ft) above the ground, and the battlemented parapet is also reasonably intact. The wall is surrounded in turn by a ditch 15 metres (49 ft) by 4 metres (13 ft) deep. Both the wall and the internal buildings were constructed from slate, which appears to have been quarried from the scarp face north-east of the castle.[3]

The domestic buildings within the wall included a kitchen, hall, solar, guest chambers, and an ante-chapel.[4] Water from a spring was piped under pressure into the castle buildings.[5] A square gate tower, largely ruined, guards the entrance to the inner castle, and may have been the first part of the castle to have been partially constructed in stone.[4] On the opposite side, a square tower projecting from the wall contains the chapel;[4] it is thought to have been a 13th-century addition. It appears to have been converted into a gun emplacement during the English Civil War.[3] An external bailey wall, apparently constructed of timber with earthwork defences, has since been destroyed, leaving no trace.[6][7] There are also historical references to a dungeon, also now vanished.[8]

The castle appears to stand upon a motte; its massive walls were, unusually for the period, sunk deep into the original motte. The effect is heightened by a surrounding ringwork, subsequently filled in on the inner side so as to appear to heap against the castle wall.[9] This may have been done to provide a garden walk around the ruin in a later period.[10]

History

editRestormel was part of the fiefdom of the Norman magnate Robert, Count of Mortain, located within the manor of Bodardle in the parish of Lanlivery.[11] Restormel Castle was probably built after the Norman Conquest of England as a motte and bailey castle around 1100 by Baldwin Fitz Turstin, the local sheriff.[12] Baldwin's descendants continued to hold the manor as vassals and tenants of the Earls of Cornwall for nearly 200 years.[11]

Constructed in the middle of a large deer park, the castle overlooked the primary crossing point over the River Fowey, a key tactical location;.[13] It may have been originally used as a hunting lodge as well as a fortification.[14]

Robert de Cardinham, lord of the manor between 1192 and 1225, built up the inner curtain walls and converted the gatehouse completely to stone, giving the castle its current design.[4] The village of Lostwithiel was established close to the castle at around the same time.[15] The castle belonged to the Cardinhams for several years, who used it in preference to their older castle at Old Cardinham. Andrew de Cardinham's daughter, Isolda de Cardinham, married Thomas de Tracey, who owned the castle until 1264.[16]

The castle was seized in 1264 without fighting by Simon de Montfort during the civil conflicts in the reign of Henry III,[17] and was seized back in turn by the former High Sheriff of Cornwall, Sir Ralph Arundell, in 1265.[18] After some persuasion, Isolda de Cardinham granted the castle to Henry III's brother, Richard of Cornwall in 1270.[19] Richard died in 1271, and his son Edmund took over Restormel as his main administrative base, building the inner chambers to the castle during his residence there and titling it his "duchy palace".[20] The castle in this period resembled a "miniature palace", with luxurious quarters and piped water.[21] It was home to stannary administration and oversaw the profitable tin-mines in the village.[22]

Crown ownership and fall into ruin

editAfter Edmund's death in 1299 the castle reverted to the Crown, and from 1337 onwards the castle was one of the 17 antiqua maneria of the Duchy of Cornwall. It was rarely used as a residence,[4] although Edward the Black Prince stayed at the castle in 1354 and 1365.[18] The prince used these occasions to gather his feudal subjects at the castle to pay him homage.[23] After the loss of Gascony, one of the key possessions of the Duchy, the contents of the castle were removed to other residences.[24] With an absent lord, the stewardship of the castle became much sought after, and the castle and its estate became known for its efficient administration.[25]

The castle is recorded as having fallen into disrepair in a 1337 survey of the possessions of the Duchy of Cornwall. It was extensively repaired by order of the Black Prince, but declined again following his death in 1376.[7] When the antiquary John Leland saw it in the 16th century, it had fallen into ruin and had been extensively robbed for its stonework; as he put it, "the timber rooted up, the conduit pipes taken away, the roofe made sale of, the planchings rotten, the wals fallen down, and the hewed stones of the windowes, dournes, and clavels, pluct out to serve private buildings; onely there remayneth an utter defacement, to complayne upon this unregarded distresse."[26]

Henry VIII converted the castle's parkland to ordinary countryside. With the castle out of use, a manor house was established during the 16th century a short distance away on lower-lying land adjoining the river. It is said to have been built on the site of a chapel dedicated to the Trinity that was destroyed during the English Reformation. Restormel Manor, now a grade II listed building, is owned by the Duchy of Cornwall and is subdivided into luxury apartments with holiday accommodation in the outbuildings.[27] During Christmas in 2009, the then Kate Middleton stayed there and won a landmark victory over a paparazzo who photographed her there.[28]

Restormel has seen action only once during its long history, when a Parliamentary garrison occupied the ruins and made some basic repairs during the Civil War. It was invested by an opposing force loyal to Charles I, led by Sir Richard Grenville, a local member of the gentry who had been the member of parliament for Fowey before the war. Grenville stormed the castle on 21 August 1644, whilst manoeuvring to encircle Parliamentary forces.[29] It is not clear whether it was subsequently slighted but in an Parliamentary survey of 1649, it was recorded to be utterly ruined, with only the outer walls still standing, and was deemed to be too badly ruined to repair and too worthless to demolish.[26]

By the 19th century it had become a popular attraction. The French writer Henri-François-Alphonse Esquiros, who visited the castle in 1865, described the ruins as forming "what the English call a romantic scene." He noted that the ivy-covered ruins attracted visitors for "for picnics and parties of pleasure".[30] In 1846 the British royal family visited the castle; arriving on their yacht, the Victoria and Albert up the River Fowey[31]

Today

editIn 1925, Prince Edward, Duke of Cornwall – later King Edward VIII – entrusted the ruin to the Office of Works.[32] In 1971 a proposal was to restore the castle, but was dropped after strong opposition.[27] A decade later, the castle was designated a scheduled monument.[3] It has never been excavated. It is now maintained by English Heritage as a tourist attraction and picnic site.[7]

Literature and popular culture

editIn her poetical illustration 'Restormel Castle, Cornwall', to a picture by Thomas Allom, Letitia Elizabeth Landon tells a spooky tale of the death of its last 'castellan or constable', which she states to be 'traditionary'.[33]

The Great Western Railway named one of their Castle class locomotives, number 5010, Restormel Castle. The locomotive was built in 1927 and withdrawn from service in 1959. There is also a Spencer Sweetpea named Restormel.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Place-names in the Standard Written Form (SWF) : List of place-names agreed by the MAGA Signage Panel. Cornish Language Partnership.

- ^ Pounds, p. 188; Pettifer, p. 21; Hull and Whitehorne, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d Historic England. "Restormel Castle (1017574)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Pettifer, p. 22.

- ^ Creighton, p. 54.

- ^ Pettifer, p. 21; Steane, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Restormel Castle (432711)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ^ Oman, pp. 109-11.

- ^ Pettifer, p.21; Hull and Whitehorne, p. 65.

- ^ Creighton, p. 83.

- ^ a b Brown, p. 192

- ^ Hull and Whitehorne, p. 64; Steane, p. 42.

- ^ A bridge further along the river later reduced the significance of the site; Creighton, p. 43.

- ^ Hull and Whitehorne, p. 64; Deacon notes that the precise location was not perfect for a castle, but would have been ideal for hunting parties, p. 64.

- ^ Paliser, p.597.

- ^ Deacon, p. 64.

- ^ Pettifer, p. 21.

- ^ a b Hull and Whitehorne, p. 64.

- ^ Hull and Whitehorne, p. 64; Emery, p. 447.

- ^ Pettifer, p. 22; Emery, p. 447.

- ^ Long, p. 105; Creighton, p. 54.

- ^ Creighton, p. 187.

- ^ Davies and Smith, p. 78.

- ^ Long, p. 105.

- ^ Emery, p. 448.

- ^ a b Hitchens & Drew, p. 468

- ^ a b Neale (2013)

- ^ Nicholl, p. 300

- ^ Memegalos, p. 196.

- ^ Esquiros, p. 17

- ^ Naylor and Naylor, p. 474.

- ^ Hull and Whitehorne, p.64.

- ^ Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1831). "poetical illustration". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1832. Fisher, Son & Co.Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1831). "picture". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1832. Fisher, Son & Co.

Bibliography

edit- Creighton, O. H. (2002) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London: Equinox.

- Davies, R. R. and Brendan Smith. (2009) Lords and Lordship in the British Isles in the Late Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deacon, Bernard. (2010) Cornwall & the Cornish. Penzance: Hodge.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Esquiros, Alphonse (1865). Cornwall and Its Coasts. London: Chapman.

- Hitchins, Fortescue; Drew, Samuel. (1824) The History of Cornwall: From the Earliest Records and Traditions, to the Present Time. London: William Penaluna.

- Hull, Lise and Stephen Whitehorne. (2008) Great Castles of Britain & Ireland. London: New Holland Publishers.

- Long, Peter. (2003) The Hidden Places of Cornwall. Aldermaston, Travel Publishing.

- Memegalos, Florene S. (2007) George Goring (1608–1657): Caroline Courtier and Royalist General. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Naylor, Robert and John Naylor. From John O' Groats to Land's End. Middlesex: The Echo Library.

- Neale, John (2013). Exploring the River Fowey. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-2341-2.

- Nicholl, Katie (2011). The Making of a Royal Romance. Random House. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4090-5187-9.

- Oman, Charles. (1926) Castles. London: Great Western Railway.

- Palliser, D. M. (2000) The Cambridge Urban History of Britain: 600 – 1540, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (1995) English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1990) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a social and political history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Steane, John. (1985) The Archaeology of Medieval England and Wales, Part 2. Beckenham: Croom Helm.