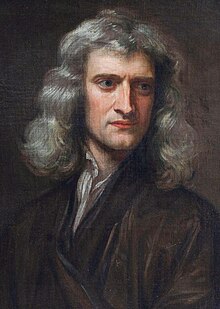

Isaac Newton (4 January 1643 – 31 March 1727)[1] was considered an insightful and erudite theologian by his Protestant contemporaries.[2][3][4] He wrote many works that would now be classified as occult studies, and he wrote religious tracts that dealt with the literal interpretation of the Bible.[5] He kept his heretical beliefs private.

Newton's conception of the physical world provided a model of the natural world that would reinforce stability and harmony in the civic world. Newton saw a monotheistic God as the masterful creator whose existence could not be denied in the face of the grandeur of all creation.[6][7] Although born into an Anglican family, and a devout but heterodox Christian,[8] by his thirties Newton held a Christian faith that, had it been made public, would not have been considered orthodox by mainstream Christians.[8] Many scholars now consider him a Nontrinitarian Arian.

He may have been influenced by Socinian christology.

Early history

editNewton was born into an Anglican family three months after the death of his father, a prosperous farmer also named Isaac Newton. When Newton was three, his mother married the rector of the neighbouring parish of North Witham and went to live with her new husband, the Reverend Barnabas Smith, leaving her son in the care of his maternal grandmother, Margery Ayscough.[9] Isaac apparently hated his step-father, and had nothing to do with Smith during his childhood.[8] His maternal uncle, the rector serving the parish of Burton Coggles,[10] was involved to some extent in the care of Isaac.

In 1667, Newton became a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge,[11] making necessary his commitment to taking Holy Orders within seven years of completing his MA, which he did the following year. He was also required to take a vow of celibacy and recognize the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England.[12] Newton considered ceasing his studies prior to completion to avoid the ordination made necessary by law of King Charles II.[1][13] He was eventually successful in avoiding the statute, assisted in this by the efforts of Isaac Barrow, as in 1676 the then Secretary of State for the Northern Department, Joseph Williamson, changed the relevant statute of Trinity College to provide dispensation from this duty.[12] Newton then embarked on an investigative study of the early history of the Church, which developed, during the 1680s, into inquiries about the origins of religion. At around the same time, he developed a scientific view on motion and matter.[13] Of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica he stated:[14]

When I wrote my treatise about our Systeme I had an eye upon such Principles as might work with considering men for the beliefe of a Deity and nothing can rejoyce me more than to find it useful for that purpose.

Christian heresy

editAccording to most scholars, Newton was Arian, not holding to Trinitarianism.[15][16][17] Scholars have generally concluded that Newton's heretical beliefs were self-taught, but he may have been influenced by then-current heretical writings; controversies over unitarianism were raging at the time.[15]

As well as rejecting the Trinity, Newton's studies led him to reject belief in the immortal soul.[15] Despite his unorthodox beliefs, Sir Isaac Newton affirmed infant baptism, in keeping with his Anglican upbringing, writing, "The Declaration by imposition of hands" is a Jewish ceremony. We call it confirmation, meaning a confirmation of what was done by the Godfathers in baptizing the Infant."[18]

Although he was not a Socinian, he shared many similar beliefs with them.[15] They were a unitarian Reformation movement in Poland. A manuscript he sent to John Locke in which he disputed the existence of the Trinity was never published. In 2019, John Rogers stated, "Heretics both, John Milton and Isaac Newton were, as most scholars now agree, Arians."[19][15]

Newton refused the sacrament of the Anglican church offered before his death.[8]

After his death, Deists sometimes claimed him as one of their own, as have Trinitarians. In fact, he was an active apologist who opposed both orthodox teachings and religious skepticism.[15]

God as masterful creator

editNewton saw God as the masterful creator whose existence could not be denied in the face of the grandeur of all creation.[20] Nevertheless, he rejected Leibniz's thesis that God would necessarily make a perfect world which requires no intervention from the creator. In Query 31 of the Opticks, Newton simultaneously made an argument from design and for the necessity of intervention:

For while comets move in very eccentric orbs in all manner of positions, blind fate could never make all the planets move one and the same way in orbs concentric, some inconsiderable irregularities excepted which may have arisen from the mutual actions of comets and planets on one another, and which will be apt to increase, till this system wants a reformation.[21]

This passage prompted an attack by Leibniz in a letter to his friend Caroline of Ansbach:

Sir Isaac Newton and his followers have also a very odd opinion concerning the work of God. According to their doctrine, God Almighty wants to wind up his watch from time to time: otherwise it would cease to move. He had not, it seems, sufficient foresight to make it a perpetual motion.[22]

Leibniz's letter initiated the Leibniz-Clarke correspondence, ostensibly with Newton's friend and disciple Samuel Clarke, although as Caroline wrote, Clarke's letters "are not written without the advice of the Chev. Newton".[23] Clarke complained that Leibniz's concept of God as a "supra-mundane intelligence" who set up a "pre-established harmony" was but a step from atheism: "And as those men, who pretend that in an earthly government things may go on perfectly well without the king himself ordering or disposing of any thing, may reasonably be suspected that they would like very well to set the king aside: so, whosoever contends, that the beings of the world can go on without the continual direction of God...his doctrine does in effect tend to exclude God out of the world".[24]

In addition to stepping in to re-form the Solar System, Newton invoked God's active intervention to prevent the stars falling in on each other, and perhaps in preventing the amount of motion in the universe from decaying due to viscosity and friction.[25] In private correspondence, Newton sometimes hinted that the force of gravity was due to an immaterial influence:

Tis inconceivable that inanimate brute matter should (without the mediation of something else which is not material) operate upon & affect other matter without mutual contact.[26]

Leibniz said that such an immaterial influence would be a continual miracle; this was another strand of his debate with Clarke.

Newton's view has been considered to be close to deism, and several biographers and scholars labelled him as a deist who is strongly influenced by Christianity.[27][28][29][30] However, he differed from strict adherents of deism in that he invoked God as a special physical cause to keep the planets in orbits.[16] He warned against using the law of gravity to view the universe as a mere machine, like a great clock, saying:

This most beautiful system of the sun, planets, and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent Being. [...] This Being governs all things, not as the soul of the world, but as Lord over all; and on account of his dominion he is wont to be called "Lord God" παντοκρατωρ [pantokratōr], or "Universal Ruler". [...] The Supreme God is a Being eternal, infinite, [and] absolutely perfect.[6]

Opposition to godliness is atheism in profession and idolatry in practice. Atheism is so senseless and odious to mankind that it never had many professors.[31][32]

On the other hand, latitudinarian and Newtonian ideas taken too far resulted in the millenarians, a religious faction dedicated to the concept of a mechanical universe, but finding in it the same enthusiasm and mysticism that the Enlightenment had fought so hard to extinguish.[33] Newton showed considerable interest in millenarianism, as he wrote about both the Book of Daniel and the Book of Revelation in his Observations Upon the Prophecies.

Newton's concept of the physical world provided a model of the natural world that would reinforce stability and harmony in the civic world.[33]

Bible

editNewton spent a great deal of time trying to discover hidden messages within the Bible. After 1690, Newton wrote a number of religious tracts dealing with the literal interpretation of the Bible. In a manuscript Newton wrote in 1704, he describes his attempts to extract scientific information from the Bible. He estimated that the world would end no earlier than 2060. In predicting this, he said, "This I mention not to assert when the time of the end shall be, but to put a stop to the rash conjectures of fanciful men who are frequently predicting the time of the end, and by doing so bring the sacred prophesies into discredit as often as their predictions fail."[34]

The Library of Trinity College, Cambridge, holds in its collections Newton's personal copy of the King James Version, which exhibits numerous marginal notes in his hand as well as about 500 reader's marks pointing to passages of particular interest to him. A note is attached to the Bible, indicating that it "was given by Sir Isaac Newton in his last illness to the woman who nursed him". The book was eventually bequeathed to the Library in 1878. The places Newton marked or annotated in his Bible bear witness to his investigations into theology, chronology, alchemy, and natural philosophy; and some of these relate to passages of the General Scholium to the second edition of the Principia. Some other passages he marked offer glimpses of his devotional practices and reveal distinct tensions in his personality. Newton's Bible appears to have been first and foremost a customized reference tool in the hands of a biblical scholar and critic.[35]

The Trinity

editNewton's work of New Testament textual criticism, An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture, was sent in a letter to John Locke on 14 November 1690. In it, he reviews evidence that the earliest Christians did not believe in the Trinity.[36]

Prophecy

editNewton relied upon the existing Scripture for prophecy, believing his interpretations would set the record straight in the face of what he considered to be, "so little understood".[37] Though he would never write a cohesive body of work on prophecy, Newton's beliefs would lead him to write several treatises on the subject, including an unpublished guide for prophetic interpretation titled Rules for interpreting the words & language in Scripture. In this manuscript, he details the requirements for what he considered to be the proper interpretation of the Bible.

End of the world vs. Start of the millennial kingdom

editIn his posthumously-published Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John, Newton expressed his belief that Bible prophecy would not be understood "until the time of the end", and that even then "none of the wicked shall understand". Referring to that as a future time ("the last age, the age of opening these things, be now approaching"), Newton also anticipated "the general preaching of the Gospel be approaching" and "the Gospel must first be preached in all nations before the great tribulation, and end of the world".[38]

Over the years, a large amount of media attention and public interest has circulated regarding largely unknown and unpublished documents, evidently written by Isaac Newton, that indicate he believed the world could end in 2060. While Newton also had many other possible dates (e.g. 2034),[39] he did not believe that the end of the world would take place specifically in 2060.[40]

Like most Protestant theologians of his time, Newton believed that the Papal Office and not any one particular Pope was the fulfillment of the Biblical predictions about Antichrist, whose rule was predicted to last for 1,260 years. They applied the day-year principle (in which a day represents a year in prophecy) to certain key verses in the books of Daniel[41] and Revelation[42] (also known as the Apocalypse), and looked for significant dates in the Papacy's rise to power to begin this timeline. Newton's calculation ending in 2060 is based on the 1,260-year timeline commencing in 800 AD when Charlemagne became the first Holy Roman Emperor and reconfirmed the earlier (756 AD) Donation of Pepin to the Papacy.[34]

2016 vs. 2060

editBetween the time he wrote his 2060 prediction (about 1704) until his death in 1727, Newton conversed, both first-hand and by correspondence, with other theologians of his time. Those contemporaries who knew him during the remaining 23 years of his life appear to be in agreement that Newton, and the "best interpreters" including Jonathan Edwards, Robert Fleming, Moses Lowman, Phillip Doddridge, and Bishop Thomas Newton, were eventually "pretty well agreed" that the 1,260-year timeline should be calculated from the year 756 AD.[43]

F. A. Cox also confirmed that this was the view of Newton and others, including himself:

The author adopts the hypothesis of Fleming, Sir Isaac Newton, and Lowman, that the 1260 years commenced in A.d. 756; and consequently that the millennium will not begin till the year 2016.[44]

Thomas Williams stated that this timeline had become the predominant view among the leading Protestant theologians of his time:

Mr. Lowman, though an earlier commentator, is (we believe) far more generally followed; and he commences the 1260 years from about 756, when, by aid of Pepin, King of France, the Pope obtained considerable temporalities. This carries on the reign of Popery to 2016, or sixteen years into the commencement of the Millennium, as it is generally reckoned.[45]

In April of 756 AD, Pepin, King of France, accompanied by Pope Stephen II entered northern Italy, forcing the Lombard King Aistulf to lift his siege of Rome and return to Pavia. Following Aistulf's capitulation, Pepin gave the newly conquered territories to the Papacy through the Donation of Pepin, thereby elevating the Pope from being a subject of the Byzantine Empire to the head of state, with temporal power over the newly constituted Papal States.

The end of the timeline is based on Daniel 8:25, which reads "he shall be broken without hand" and is understood to mean that the end of the Papacy will not be caused by any human action.[46] Volcanic activity is described as the means by which Rome will be overthrown.[47]

Antichrist will retain some part of his dominion over the nations till about the year 2016. And when the 1260 years are expired, Rome itself, with all its magnificence, will be absorbed in a lake of fire, sink into the sea, and rise no more at all for ever.[48]

In 1870, the newly formed Kingdom of Italy annexed the remaining Papal States, depriving the Popes of any temporal rule for the next 59 years. Unaware that Papal rule would be restored (albeit on a greatly diminished scale) in 1929 as head of the Vatican City state, the historicist view that the Papacy is the Antichrist and the associated timelines delineating his rule rapidly declined in popularity as one of the defining characteristics of the Antichrist (i.e. that he would also be a political temporal power at the time of the return of Jesus) were no longer met.

Eventually, the prediction was largely forgotten and no major Protestant denomination currently subscribes to this timeline.

Despite the dramatic nature of a prediction of the end of the world, Newton may not have been referring to the 2060 date as a destructive act resulting in the annihilation of the earth and its inhabitants, but rather one in which he believed the world was to be replaced with a new one based upon a transition to an era of divinely inspired peace. In Christian theology, this concept is often referred to as The Second Coming of Jesus Christ and the establishment of Paradise by The Kingdom of God on Earth.[39]

Other beliefs

editHenry More's belief in the universe and rejection of Cartesian dualism may have influenced Newton's religious ideas. Later works—The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1728) and Observations Upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John (1733)—were published after his death.[49]

Newton and Boyle's mechanical philosophy was promoted by rationalist pamphleteers as a viable alternative to the pantheists and enthusiasts, and was accepted hesitantly by orthodox clergy as well as dissident preachers like the latitudinarians.[33] The clarity and simplicity of science was seen as a way in which to combat the emotional and mystical superlatives of superstitious enthusiasm, as well as the threat of atheism.[33]

The attacks made against pre-Enlightenment magical thinking, and the mystical elements of Christianity, were given their foundation with Boyle's mechanical conception of the universe. Newton gave Boyle's ideas their completion through mathematical proofs, and more importantly was very successful in popularizing them.[49] Newton refashioned the world governed by an interventionist God into a world crafted by a God that designs along rational and universal principles.[50] These principles were available for all people to discover, allowed man to pursue his own aims fruitfully in this life, not the next, and to perfect himself with his own rational powers.[51]

Writings

editHis first writing on the subject of religion was Introductio. Continens Apocalypseos rationem generalem (Introduction. Containing an explanation of the Apocalypse), which has an unnumbered leaf between folios 1 and 2 with the subheading De prophetia prima,[52] written in Latin some time prior to 1670. Written subsequently in English was Notes on early Church history and the moral superiority of the 'barbarians' to the Romans. His last writing, published in 1737 with the miscellaneous works of John Greaves, was entitled A Dissertation upon the Sacred Cubit of the Jews and the Cubits of the several Nations.[4] Newton did not publish any of his works of biblical study during his lifetime.[3][53] All of Newton's writings on corruption in biblical scripture and the church took place after the late 1670s and prior to the middle of 1690.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Christianson, Gale E. (19 September 1996). Isaac Newton and the scientific revolution. – 155 pages Oxford portraits in science Oxford University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-19-509224-4. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ Austin, William H. (1970), "Isaac Newton on Science and Religion", Journal of the History of Ideas, 31 (4): 521–542, doi:10.2307/2708258, JSTOR 2708258

- ^ a b c [ENGLISH & LATIN] "The Newton Project Newton's Views on the Corruptions of Scripture and the Church". Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ a b Professor Rob Iliffe (AHRC Newton Papers Project) THE NEWTON PROJECT – Newton's Religious Writings [ENGLISH & LATIN] prism.php44. University of Sussex. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ "Newton's Views on Prophecy". The Newton Project. 5 April 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ a b Principia, Book III; cited in; Newton's Philosophy of Nature: Selections from his writings, p. 42, ed. H.S. Thayer, Hafner Library of Classics, NY, 1953.

- ^ A Short Scheme of the True Religion, manuscript quoted in Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton by Sir David Brewster, Edinburgh, 1850; cited in; ibid, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Richard S. Westfall – Indiana University The Galileo Project. (Rice University). Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ Nichols, John Bowyer (1822). Illustrations of the literary history of the eighteenth century: Consisting of authentic memoirs and original letters of eminent persons; and intended as a sequel to the Literary anecdotes, Volume 4. Nichols, Son, and Bentley. p. 32.

- ^ C. D. Broad (2000). Ethics and the History of Philosophy: Selected Essays. Vol. 1. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-415-22530-4.

- ^ Cambridge University Alumni Database Retrieved 29 January 2012

- ^ a b Professor Rob Iliffe (AHRC Newton Papers Project) THE NEWTON PROJECT prism.php15. University of Sussex. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ a b Cambridge University Library .ac. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ S.D.Snobelen (University of King's College) – To Discourse of God : Isaac Newton's Heterdox Theology and Natural Philosophy Nova Scotia Retrieved 29 January 2012

- ^ a b c d e f Snobelen, Stephen D. (1999). "Isaac Newton, heretic : the strategies of a Nicodemite" (PDF). British Journal for the History of Science. 32 (4): 381–419. doi:10.1017/S0007087499003751. S2CID 145208136. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2014.

- ^ a b Avery Cardinal Dulles. The Deist Minimum. 2005.

- ^ Richard Westfall, Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton, (1980) pp. 103, 25.

- ^ "Seven Statements on Religion". The Newton Project.

- ^ John Rogers, "Newton's Arian Epistemology and the Cosmogony of Paradise Lost." ELH: English Literary History 86.1 (2019): 77-106 online.

- ^ Webb, R.K. ed. Knud Haakonssen. "The emergence of Rational Dissent." Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in eighteenth-century Britain. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1996. p19.

- ^ Newton, 1706 Opticks (2nd Edition), quoted in H. G. Alexander 1956 (ed): The Leibniz-Clarke correspondence, University of Manchester Press.

- ^ Leibniz, first letter, in Alexander 1956, p. 11

- ^ Caroline to Leibniz, 10 January 1716, quoted in Alexander 1956, p. 193. (Chev. = Chevalier i.e. Knight.)

- ^ Clarke, first reply, in Alexander 1956 p. 14.

- ^ H.W. Alexander 1956, p. xvii

- ^ Newton to Bentley, 25 February 1693

- ^ Force, James E.; Popkin, Richard Henry (1990). Force, James E.; Popkin, Richard Henry (eds.). Essays on the Context, Nature, and Influence of Isaac Newton's Theology. Springer. p. 53. ISBN 9780792305835.

Newton has often been identified as a deist. ...In the 19th century, William Blake seems to have put Newton into the deistic camp. Scholars in the 20th-century have often continued to view Newton as a deist. Gerald R. Cragg views Newton as a kind of proto-deist and, as evidence, points to Newton's belief in a true, original, monotheistic religion first discovered in ancient times by natural reason. This position, in Cragg's view, leads to the elimination of the Christian revelation as neither necessary nor sufficient for human knowledge of God. This agenda is indeed the key point, as Leland describes above, of the deistic program which seeks to "set aside" revelatory religious texts. Cragg writes that, "In effect, Newton ignored the claims of revelation and pointed in a direction which many eighteenth-century thinkers would willingly follow." John Redwood has also recently linked anti-Trinitarian theology with both "Newtonianism" and "deism."

- ^ Gieser, Suzanne (14 February 2005). The Innermost Kernel: Depth Psychology and Quantum Physics. Wolfgang Pauli's Dialogue with C.G. Jung. Springer. pp. 181–182. ISBN 9783540208563.

Newton seems to have been closer to the deists in his conception of God and had no time for the doctrine of the Trinity. The deists did not recognize the divine nature of Christ. According to Fierz, Newton's conception of God permeated his entire scientific work: God's universality and eternity express themselves in the dominion of the laws of nature. Time and space are regarded as the 'organs' of God. All is contained and moves in God but without having any effect on God himself. Thus space and time become metaphysical entities, superordinate existences that are not associated with any interaction, activity or observation on man's part.

- ^ McCauley, Joseph L. (1997). Classical Mechanics: Transformations, Flows, Integrable and Chaotic Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521578820.

Newton (1642–1727), as a seventeenth century nonChristian Deist, would have been susceptible to an accusation of heresy by either the Anglican Church or the Puritans.

- ^ Hans S. Plendl, ed. (1982). Philosophical problems of modern physics. Reidel. p. 361.

Newton expressed the same conception of the nature of atoms in his deistic view of the Universe.

- ^ Brewster, Sir David. A Short Scheme of the True Religion, manuscript quoted in Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton Edinburgh, 1850.

- ^ "A short Schem of the true Religion". The Newton Project. East Sussex: University of Sussex. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d Jacob, Margaret C. (1976). The Newtonians and the English Revolution: 1689–1720.

- ^ a b "Papers Show Isaac Newton's Religious Side, Predict Date of Apocalypse". Associated Press. 19 June 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Joalland, Michael. "Isaac Newton Reads the King James Version: The Marginal Notes and Reading Marks of a Natural Philosopher". Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 113, no. 3 (2019): 297–339 (https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/704518?journalCode=pbsa)

- ^ Parker, Kim Ian (February 2009). "Newton, Locke and the Trinity: Sir Isaac's comments on Locke's: A Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistle of St Paul to the Romans". Scottish Journal of Theology. 62 (1): 40–52. doi:10.1017/s0036930608004626.

- ^ Newton, Isaac (5 April 2007). "The First Book Concerning the Language of the Prophets". The Newton Project. Archived from the original on 8 November 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John by Sir Isaac Newton, 1733, J. DARBY and T. BROWNE, Online

- ^ a b Snobelen, Stephen D. "Statement on the date 2060". Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "A time and times and the dividing of times": Isaac Newton, the Apocalypse and 2060 AD Snobelen, S Can J Hist (2003) vol 38 Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ the "time, times and half a time" of Daniel 7:25 and 12:7

- ^ the "42 months" of Revelation 11:2 and 13:5 equals the "1260 days" of Revelation 11:3 and 12:6

- ^ Jonathan Edwards ”History of Redemption" New York: T. and J. Swords (1793) page 431: "The Beginning of the reign of Antichrist.] The best interpreters (as Mr. Fleming, Sir I. Newton, Mr. Lowman, Dr. Doddridge, Bp. Newton, and Mr. Reader) are pretty well agreed that this reign is to be dated from about A. D. 756, when the Pope began to be a temporal power, (that is, in prophetic language, a beast) by assuming temporal dominion; 1260 years from this period will bring us to about A. D. 2000, and about the 6000th year of the world, which agrees with a tradition at least as ancient as the epistle ascribed to the apostle Barnabas (f 15.] which says, that " in six thousand years shall all things be accomplished."

- ^ Rev. F.A. Cox "Outlines of Lectures on the Book of Daniel" London: Westley and Davis (1833) 2nd Edition Page 152

- ^ Thomas Williams "The Cottage Bible and family expositor" Hartford: D.F. Robinson and H. F. Sumner (1837) Vol. 2-page 1417

- ^ Bishop Thomas Newton "DISSERTATIONS ON THE PROPHECIES" London: J.F. and C. Rivington (1789) 8th Edition Page 327: "As the stone in Nebuchadnezzar's dream was cut out of the mountain without hands, that is not by human, but by supernatural means; so the little horn shall be broken without hand, not die the common death, not fall by the hand of men, but perish by a stroke from heaven."

- ^ East Apthorp, D.D. "Discourses on Prophecy" (1786) Discourse XI, Page 273: "Rome the seat of Antichrist will be consumed with fire, at the coming of Christ, or when the period of her apostacy is expired, in 1260 years from the rise of Antichrist." Page 275: "...present Rome, when by an eruption of fire the mountainous soil, being undermined, will fall into an abyss, and be covered with the sea*

- ^ Rev. David Simpson "A Plea for Religion and the Sacred Writings" London: W. Baynes, and Paternoster-Row. (1808) 5th Edition, pages 131 and 133.

- ^ a b Westfall, Richard S. (1973) [1964]. Science and Religion in Seventeenth-Century England. U of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06190-7.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Martin. ed. Knud Haakonssen. "The Enlightenment, politics and providence: some Scottish and English comparisons." Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in eighteenth-century Britain. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1996. p64.

- ^ Frankel, Charles. The Faith of Reason: The Idea of Progress in the French Enlightenment. King's Crown Press, New York: 1948. p1.

- ^ The Newton Project, THEM00046, retrieved 20 January 2014

- ^ James E. Force; Richard Henry Popkin (1990). Essays on the Context, Nature, and Influence of Isaac Newton's Theology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-7923-0583-5.

Further reading

edit- Eamon Duffy, "Far from the Tree" The New York Review of Books, vol. LXV, no. 4 (8 March 2018), pp. 28–29; a review of Rob Iliffe, Priest of Nature: the Religious Worlds of Isaac Newton, (Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Feingold, Mordechai. "Isaac Newton, Heretic? Some Eighteenth-Century Perceptions." in Reading Newton in Early Modern Europe (Brill, 2017) pp. 328-345.

- Feingold, Mordechai. "The religion of the young Isaac Newton." Annals of science 76.2 (2019): 210-218.

- Greenham, Paul. "Clarifying divine discourse in early modern science: divinity, physico-theology, and divine metaphysics in Isaac Newton’s chymistry." The Seventeenth Century 32.2 (2017): 191-215. doi:10.1080/0268117X.2016.1271744.

- Iliffe, Rob. Priest of Nature: The Religious Worlds of Isaac Newton. Oxford University Press: 2017, 536 pp. online review

- Joalland, Michael. "Isaac Newton Reads the King James Version: The Marginal Notes and Reading Marks of a Natural Philosopher". Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 113, no. 3 (2019): 297–339. doi:10.1086/704518.

- Manuel, Frank. E. The Religion of Isaac Newton. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974.

- Rogers, John. "Newton's Arian Epistemology and the Cosmogony of Paradise Lost." ELH: English Literary History 86.1 (2019): 77-106 online.

- Snobelen, Stephen D. "Isaac Newton, heretic: the strategies of a Nicodemite." British journal for the history of science 32.4 (1999): 381–419. online

External links

edit- Isaac Newton Theology, Prophecy, Science and Religion – writings on Newton by Stephen Snobelen

- The Newton Manuscripts at the National Library of Israel – the collection of all his religious writings