The Rashidun Caliphate (Arabic: ٱلْخِلَافَةُ ٱلرَّاشِدَةُ, romanized: al-Khilāfah ar-Rāšidah) consisted of the first four successive caliphs (lit. 'successors') — Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali, collectively known as the Rashidun, or "Rightly Guided" caliphs (الْخُلَفاءُ الرّاشِدُونَ, al-Khulafāʾ ar-Rāšidūn) and the short rule of Hasan ibn Ali (who briefly succeeded Ali) — who led the Muslim community/polity from the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (in 632 CE), to the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate (in 661 CE). The Caliphate's first 25-years were characterized by rapid military expansion during which it became the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in West Asia and Northeast Africa. By the 650s, in addition to the Arabian Peninsula, the caliphate had subjugated the Levant to the Transcaucasus in the north; North Africa from Egypt to present-day Tunisia in the west; and the Iranian Plateau to parts of Central and South Asia in the east. It ended in a five-year period of internal strife. The title Rashidun comes from the belief in Sunni Islam that the caliphs were 'rightly guided' (the meaning of al-Rāshidūn; الراشدون), and therefore constituted a religious model (sunnah) to be followed and emulated.[3] The caliphs are also known in Muslim history as the "orthodox" or "patriarchal" caliphs.[4]

Rashidun Caliphate | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 632–661 | |||||||||||||||

The Rashidun Caliphate at its greatest extent under Uthman, c. 654 | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Arabic | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Various regional languages[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||||||

| Caliph | |||||||||||||||

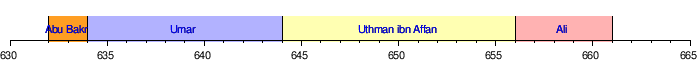

• 632–634 | Abu Bakr (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 634–644 | Umar | ||||||||||||||

• 644–656 | Uthman | ||||||||||||||

• 656–661 | Ali | ||||||||||||||

• 661 | Hasan (last) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

| 632 | |||||||||||||||

| 633–654 | |||||||||||||||

• Ascension of Umar | 634 | ||||||||||||||

• Assassination of Umar and Ascension of Uthman | 644 | ||||||||||||||

• Assassination of Uthman and ascension of Ali | 656 | ||||||||||||||

| 661 | |||||||||||||||

• First Fitna (internal conflict) ends after Hasan's abdication | 661 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 655[2] | 6,400,000 km2 (2,500,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Following Muhammad's death in June 632, Muslim leaders debated who should succeed him. Unlike later caliphs, each of the four Rashidun were chosen by some form of a small group of high-ranking companions of the Prophet in shūrā (lit. 'consultation')[a] or appointed by their predecessor.[b] Muhammad's close companion Abu Bakr (r. 632–634), of the Banu Taym clan, was elected the first caliph in Medina and began the conquest of the Arabian Peninsula. The only Rashidun not to die by assassination, he was succeeded by Umar (r. 634–644), his appointed successor from the Banu Adi clan. Under Umar, the caliphate expanded at an unprecedented rate, conquering more than two-thirds of the Byzantine Empire and nearly the entire Sasanian Empire.

After Umar's assassination, Uthman (r. 644–656), a member of the Banu Umayya clan, was chosen as Caliph. He concluded the conquest of Persia in 651 and continued expeditions into the Byzantine territories. Uthman was assassinated in June 656, and succeeded by Ali (r. 656–661), a member of the Banu Hashim clan, who transferred the capital to Kufa. Ali presided over the civil war called the First Fitna as his suzerainty was unrecognized by Uthman's kinsman and Syria's governor Mu'awiya ibn Abu Sufyan (r. 661–680), who believed that Uthman's murderers should be punished immediately. Additionally, a third faction known as Kharijites, who were former supporters of Ali, rebelled against both Ali and Mu'awiya after refusing to accept the arbitration in the Battle of Siffin. The war led to the overthrow of the Rashidun Caliphate and the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate in 661 by Mu'awiya. (A minority of sources include Ali's son Hasan as a fifth Rashidun for his claim to the caliphate from January to August 661.)[c] It also permanently consolidated the divide between Sunni and Shia Muslims, with Shia Muslims believing Ali to be the first rightful caliph and Imam after Muhammad, favouring his bloodline connection to Muhammad.[9]

Etymology

editThe Arabic word rāshidūn (singular: rāshid راشد) means "rightly-guided". The reign of these four caliphs is considered in Sunni Islam to have been 'rightly-guided', meaning that it constitutes a model (sunnah) to be followed and emulated from a religious point of view.[10] This term is not used by Shia Muslims, who reject the rule of the first three caliphs as illegitimate.[11]

History

editTimeline

edit

(Note that a caliph's succession does not necessarily occur on the first day of the new year.)

Abu Bakr's reign (632–634)

editOrigin and accession to Caliphate

editAfter Muhammad's death in 632 CE (11 AH), a gathering of the Ansar (lit. 'Helpers'), the natives of Medina, took place in the Saqifah (courtyard) of the Banu Sa'ida clan. The general belief at the time was that the purpose of the meeting was for the Ansar to decide on a new leader of the Muslim community among themselves, with the intentional exclusion of the Muhajirun (migrants from Mecca), though this has later become the subject of debate.[12]

Nevertheless, Abu Bakr and Umar, both prominent companions of Muhammad, upon learning of the meeting became concerned about a potential coup and hastened to the gathering. Upon arriving, Abu Bakr addressed the assembled men with a warning that any attempt to elect a leader outside of Muhammad's own tribe, the Quraysh, would likely result in dissension as only they can command the necessary respect among the community. He then took Umar and another companion, Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah, by the hand and offered them to the Ansar as potential choices. He was countered with the suggestion that the Quraysh and the Ansar choose a leader each from among themselves, who would then rule jointly. The group grew heated upon hearing this proposal and began to argue amongst themselves. Umar hastily took Abu Bakr's hand and swore his own allegiance to the latter, an example followed by Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, the Ansar, the Qurayshtribe and other gathered men.[13] Abu Bakr adopted the title of Khalīfaṫ Rasūl Allāh (خَلِيفةُ رَسُولِ اللهِ, "Successor of the Messenger of God") or simply caliph.[14]

Sunni Muslims argue Abu Bakr was near-universally accepted as head of the Muslim community (under the title of Caliph) as a result of Saqifah, though he did face contention as a result of the rushed nature of the event. Shia Muslims argue Muhammad's Medinan companions debated which of them should succeed him in running the affairs of the Muslims while Muhammad's household was busy with his burial.[15]

Several companions, most prominent among them being Ali ibn Abi Talib, initially refused to acknowledge his authority.[16] Ali may have been reasonably expected to assume leadership, being both cousin and son-in-law to Muhammad.[17] The theologian Ibrahim al-Nakha'i stated that Ali also had support among the Ansar for his succession, explained by the genealogical links he shared with them. Whether his candidacy for the succession was raised during Saqifah is unknown, though it is not unlikely.[18] Abu Bakr later sent Umar to confront Ali to gain his allegiance, resulting in an altercation which may have involved violence.[19] However, after six months the group made peace with Abu Bakr and Ali offered him his fealty.[20]

Ridda Wars

editTroubles emerged soon after Muhammad's death, threatening the unity and stability of the new community and state. Apostasy, (in the form of refusal to obey and pay revenue to Abu Bakr), spread to every tribe in the Arabian Peninsula with the exception of the people in Mecca and Medina, the Banu Thaqif in Ta'if and the Bani Abdul Qais of Oman. In some cases, entire tribes apostatized. Others merely withheld zakat, the alms tax, without formally challenging Islam. Many tribal leaders made claims to prophethood; some made it during the lifetime of Muhammad. The first incident of apostasy was fought and concluded while Muhammad still lived; a supposed prophet Aswad Ansi arose and invaded South Arabia;[21] he was killed on 30 May 632 (6 Rabi' al-Awwal, 11 Hijri) by Governor Fērōz of Yemen, a Persian Muslim.[22] The news of his death reached Medina shortly after the death of Muhammad. The apostasy of al-Yamama was led by another supposed prophet, Musaylimah,[23] who arose before Muhammad's death; other centers of the rebels were in the Najd, Eastern Arabia (known then as al-Bahrayn) and South Arabia (known as al-Yaman and including the Mahra). Many tribes claimed that they had submitted to Muhammad and that with Muhammad's death, their allegiance was ended.[23] Caliph Abu Bakr insisted that they had not just submitted to a leader but joined an ummah (أُمَّـة, community) of which he was the new head.[23] The result of this situation was the Ridda wars.[23]

The campaign against Apostasy or Ridda wars were fought and completed during the eleventh year of the Hijri. The year 12 Hijri dawned on 18 March 633 with the Arabian peninsula united under the caliph in Medina.[24] Abu Bakr divided the Muslim army into several corps. The strongest corps, and the primary force of the Muslims, was the corps of Khalid ibn al-Walid. This corps was used to fight the most powerful of the rebel forces. Other corps were given areas of secondary importance in which to bring the less dangerous apostate tribes to submission. Abu Bakr's plan was first to clear Najd and Western Arabia near Medina, then tackle Malik ibn Nuwayrah and his forces between the Najd and al-Bahrayn, and finally concentrate against the most dangerous enemy, Musaylimah and his allies in al-Yamama. After a series of successful campaigns Khalid ibn al-Walid defeated Musaylimah in the Battle of Yamama.[25]

Expeditions to Persia and Syria

editAfter Abu Bakr unified Arabia under Islam, he began the incursions into the Byzantine Empire and the Sasanian Empire. Whether or not he intended a full-out imperial conquest is hard to say; he did, however, set in motion a historical trajectory that in just a few short decades would lead to one of the largest empires in history. Abu Bakr began with Iraq, the richest province of the Sasanian Empire.[26] He sent general Khalid ibn al-Walid to invade the Sassanian Empire in 633.[26] He thereafter also sent four armies to invade the Roman province of Syria,[27] but the decisive operation was only undertaken when Khalid, after completing the conquest of Iraq, was transferred to the Syrian front in 634.[28]

Umar's reign (634–644)

editUmar ibn al-Khattab (Arabic: عمر ابن الخطاب, romanized: ʿUmar ibn al-Khattāb, c. 586–590 – 644[29]: 685 ) c. 2 November (Dhu al-Hijjah 26, 23 Hijri[30]) was a leading companion and adviser to Muhammad, and father-in-law by his daughter Hafsa bint Umar's marriage to Muhammad. He was appointed by a dying Abu Bakr to be his successor and took power on 23 August 634, becoming the second Muslim caliph after Muhammad's death.[31] At least according to Laura Veccia Vaglieri, the expansion of Islam from an "isolated episode" in Arab history, to an event of "worldwide importance", can be attributed to Umar's political skills.[32]

Upon his accession, Umar adopted the title amir al-mu'minin (Commander of the Faithful) which later became the standard title of caliphs.[33] During his 10-year reign, the Islamic empire expanded at an unprecedented rate. The new caliph continued the war of conquests begun by his predecessor, pushing further into the Sassanian Empire, north into Byzantine territory, and went into Egypt.[34] These were regions of great wealth controlled by powerful states, but the long conflict between Byzantines and Persians had left both sides militarily exhausted, and the Islamic armies easily prevailed against them. By 640, they had brought all of Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine under the control of the Rashidun Caliphate; Egypt was conquered by 642, and almost the entire Sassanian Empire by 643.[35]

While the caliphate continued its rapid expansion, Umar laid the foundations of a political structure that could hold it together. He created the Diwan, a bureau for transacting government affairs. The military was brought directly under state control and into its pay. Crucially, in conquered lands, Umar did not require that non-Muslim populations convert to Islam, nor did he try to centralize government. Instead, he allowed subject populations to retain their religion, language, and customs, and he left their government relatively untouched, imposing only a governor (amir) and a financial officer called an amil. These new posts were integral to the efficient network of taxation that financed the empire.

With the bounty secured from conquest, Umar was able to support its faith in material ways: the companions of Muhammad were given pensions on which to live, allowing them to pursue religious studies and exercise spiritual leadership in their communities and beyond. Umar is also remembered for establishing the Islamic calendar; like the Arabian calendar, it is lunar, but the origin is set in 622, the year of the Hijra when Muhammad emigrated to Medina.

Upon entering Jerusalem, Umar ordered that rubbish be cleared away from the mount of the Temple of Solomon and that a mosque be built there.[36]

While Umar was leading the morning prayers in 644, he was assassinated by the Persian slave Abu Lu'lu'a Firuz.[37][38][39][page needed] He appointed Suhayb ibn Sinan to lead the prayers.[40]

Uthman's reign (644–656)

editUthman ibn Affan (Arabic: عثمان ابن عفان, romanized: ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān) (c. 579 – 17 June 656), who became the third caliph at the age of 70, was one of the early companions, and son in law of Muhammad by marriage to two of Muhammad and Khadija daughters Ruqayyah and Umm Kulthum. Uthman was born into the powerful Umayyad clan of the Meccan Quraysh tribe. Under his leadership, the empire expanded into Fars (present-day Iran), some of Khorasan (present-day Afghanistan), and Armenia.[41] His rule ended when he was assassinated. Uthman is perhaps best known for forming the committee which was tasked with producing copies of the Quran based on text that had been gathered separately on parchment, bones and rocks during the lifetime of Muhammad. Uthman sent copies of the sacred text to each of the Muslim cities and garrison towns, and destroyed variant texts.[42]

Election of Uthman

editBefore Umar died, he appointed a committee of six men to decide on the next caliph and charged them with choosing one of their own numbers. All of the men, like Umar, were from the tribe of Quraysh.

The committee narrowed down the choices to two: Uthman and Ali. Ali was from the Banu Hashim clan (the same clan as Muhammad) of the Quraysh tribe, and he was the cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad and had been one of his companions from the inception of his mission. Uthman was from the Umayyad clan of the Quraysh. He was the second cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad and one of the early converts of Islam. Uthman was ultimately chosen.

Uthman reigned for twelve years as a caliph. During the first half of his reign, he was the most popular caliph among all the Rashiduns, while in the latter half of his reign he met increasing opposition, led by the Egyptians and concentrated around Ali, who would albeit briefly, succeed Uthman as caliph.

Despite internal troubles, Uthman continued the wars of conquest started by Umar. The Rashidun army conquered North Africa from the Byzantines and even raided Spain, conquering the coastal areas of the Iberian Peninsula, as well as the islands of Rhodes and Cyprus.[citation needed] Coastal Sicily was raided in 652.[43] The Rashidun army fully conquered the Sasanian Empire, and its eastern frontiers extended up to the lower Indus River.[41]

Uthman's most lasting project was the final compilation of the Qur'an. Under his authority diacritics were written with Arabic letters so that non-native speakers of Arabic could easily read the Qur'an.

Assassination of Uthman

editAfter a protest turned into a siege on his house, Uthman refused to initiate any military action, in order to avoid civil war between Muslims and preferred to negotiate a peaceful solution.[citation needed] After the negotiations, the protesters returned but found a man following them, holding an order to execute them, at which point, the protesters returned to Uthman's home, bearing the order. Uthman swore that he did not write the order and to talk the protesters down. The protesters responded by demanding he step down as caliph. Uthman refused and returned to his room, whereupon the protesters broke into Uthman's house from the back and killed him while he was reading the Qur'an.[38][39][page needed][44] It was later discovered that the order to kill the rebels did not, in fact, originate from Uthman, but was, rather, part of a conspiracy to overthrow him.[citation needed]

Ali's reign (656–661)

editAli ibn Abi Talib (Arabic: علي ابن أبي طالب, romanized: ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib) was Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law.[45] The fourth caliph in Sunni Islam, in Shia Islam, Ali is considered the rightful successor of Muhammad whose appointment was announced at the event of Ghadir Khumm and earlier in his prophetic mission.[46] Among the good and significant deeds he is credited with in Islamic literature, is being the first male to embrace Islam and the person who offered his support when Muhammad first presented Islam to his relatives;[47][48][49][50][51] facilitating Muhammad's safe escape to Medina by risking his life as the decoy.[52][53][54][55][56] swearing a pact of brotherhood with Muhammad in Medina; taking the hand of Muhammad's daughter, Fatimah, in marriage;[57][58][59] acting as Muhammad's secretary in Medina, and serving as his deputy during the expedition of Tabuk.[60] being (according to many) the most able warrior in Muhammad's army and one of the two Muslim men who represented Islam against a Christian delegation from Najran.[61][62][63][64] playing a key role in the collection of the Quran, the central text of Islam.[65]

Crisis and fragmentation

editFollowing Uthman's assassination, Muhammad's cousin Ali was elected caliph by the rebels and townspeople of Medina.[66] He transferred the capital to Kufa, a garrison city in Iraq.[67] Soon thereafter, Ali dismissed several provincial governors, some of whom were relatives of Uthman, and replaced them with trusted aides, such as Malik al-Ashtar and Salman the Persian.

Demands to take revenge for the assassination of Caliph Uthman rose among parts of the population, and a large army of rebels led by Zubayr, Talha and the widow of Muhammad, Aisha, set out to fight the perpetrators. The army reached Basra and captured it, whereupon 4,000 suspected seditionists were put to death. Subsequently, Ali turned towards Basra and the caliph's army met the rebel army. Though neither Ali nor the leaders of the opposing force, Talha and Zubayr, wanted to fight, a battle broke out at night between the two armies. It is said, according to Sunni Muslim traditions, that those who were involved in the assassination of Uthman initiated combat, as they were afraid that negotiations between Ali and the opposing army would result in their capture and execution. The battle thus fought was the first battle between Muslims and is known as the Battle of the Camel. Ali emerged victoriously and the dispute was settled. The eminent companions of Muhammad, Talha, and Zubayr, were killed in the battle and Ali sent his son Hasan ibn Ali to escort Aisha back to Medina.

Thereafter, there rose another cry for revenge for the blood of Uthman, this time by Mu'awiya, a kinsman of Uthman and governor of the province of Syria. However, it is regarded more as an attempt by Mu'awiya to assume the caliphate, rather than to take revenge for Uthman's murder. Ali fought Mu'awiya's forces to a stalemate at the Battle of Siffin, and then lost a controversial arbitration that ended with the arbiter, 'Amr ibn al-'As, pronouncing his support for Mu'awiya. After this Ali was forced to fight the Battle of Nahrawan against the rebellious Kharijites, a faction of his former supporters who, as a result of their dissatisfaction with the arbitration, opposed both Ali and Mu'awiya. Weakened by this internal rebellion and a lack of popular support in many provinces, Ali's forces lost control over most of the caliphate's territory to Mu'awiya while large sections of the empire—such as Sicily, North Africa, the coastal areas of Spain and some forts in Anatolia—were also lost to outside empires.

In 661, Ali was assassinated by Ibn Muljam as part of a Kharijite plot to assassinate all the different Islamic leaders in an attempt to end the civil war, but the Kharijites failed to assassinate Mu'awiya and 'Amr ibn al-'As.

Ali's son Hasan briefly assumed the caliphate for six months and came to an agreement with Mu'awiya to fix relations between the two groups of Muslims that were each loyal to one of the two men. The treaty stated that Mu'awiya would not name a successor during his reign, and that he would let the Islamic world choose the next leader. This treaty would later be broken by Mu'awiya as he named his son Yazid I successor. Hasan was assassinated,[68] and Mu'awiya founded the Umayyad Caliphate, supplanting the Rashidun Caliphate.[38][39][page needed]

Military expansion

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

The Rashidun Caliphate expanded steadily; within the span of 24 years, a vast territory was conquered comprising Mesopotamia, the Levant, parts of Anatolia, and most of the Sasanian Empire.

Some explanations for the success of the Arab invasion of the empires to the north, west and east initiated by the Rashidun were the weakening of the two empires brought on by wars between them[69] (especially the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628),[70] and by the Plague of Justinian,[71] which crippled both states. Arab tribes had served as mercenaries for both empires in decades prior to the invasion and the experience of gave them valuable military tactical skills, and familiarity with the battlefields they would fight on against the two empires.[72][73] Prior to the invasion a good number of Arab infiltrators, known as musta 'riba "self-styled Arabs", migrated into Syria, Palestine and Iraq. They shared Arab language and customs and "received the invaders with enthusiasm", sometimes joining the invaders' forces.[74] The buffer states of the Lakhmids and Ghasanids that had protected the empires in earlier times had disappeared by the time of the invasion. Other factors include the Arab Bedouin love of raiding and robbing sedentary peoples;[74] the willingness of Bedouin tribes to cease their time honored practice of raiding each other and obey the commands of Hijazi Muslim leaders;[75] and perhaps most decisively the Islamic belief of the invaders that conquering the unbelievers' land was a holy war/jihad of the sword, and that booty taken by them was divinely ordained reward for the invaders.[74]

The Arab conquests began as raids against the empires, but quickly escalated as the raiders discovered that Byzantines and Persians gave little resistance their assault.[76]

Conquest of the Sasanian Empire

editThe first military move following the suppression of rebellion in Arabia, was the invasion of the Sasanian Empire. In 633 Caliph Abu Bakr sent troops out to Sasanian-controlled Iraq, i.e. southern modern-day Iraq.[75] Abu Bakr sent his general, Khalid ibn al-Walid, to conquer Mesopotamia after the Ridda wars. After entering Iraq with his army of 18,000,[77] Khalid won decisive victories in four consecutive battles: the Battle of Chains, fought in April 633; the Battle of River, fought in the third week of April 633;[78] the Battle of Walaja,[79] fought in May 633 (where he successfully used a pincer movement), and the Battle of Ullais, fought in mid-May of 633.[80] In the last week of May 633, the capital city of Iraq fell to the Muslims after initial resistance in the Battle of Hira.[81]

After resting his armies, Khalid moved in June 633 towards Anbar, which resisted and was defeated, and eventually surrendered after a siege of a few weeks in July 633. Khalid then moved towards the south, and conquered the city of Ein ul Tamr in the last week of July 633. [82] By now, almost the whole of Iraq was under Islamic control. Khalid received a call for help from Dumat al-Jandal in Northern Arabia, where another Muslim general, Iyad ibn Ghanm, was trapped among the rebel tribes. Khalid diverted there and defeated the rebels in the Battle of Dawmat al-Jandal in the last week of August 633.[83] Returning from Arabia, he received news that a large Persian army was assembling. Within a few weeks, he decided to defeat them piecemeal in order to avoid the risk of defeat by a large unified Persian army. Four divisions of Persian and Christian Arab auxiliaries were present at Hanafiz, Zumiel, Sanni, and Muzieh.[84]

In November 633, Khalid divided his army into three units, and attacked these auxiliaries one by one from three different sides at night, starting with the Battle of Muzieh, then the Battle of Sanni, and finally the Battle of Zumail. These devastating defeats ended Persian control over Iraq. In December 633, Khalid reached the border city of Firaz, where he defeated the combined forces of the Sasanian Persians, Byzantines and Christian Arabs in the Battle of Firaz. This was the last battle in his conquest of Iraq.[citation needed]

Khalid then left Mesopotamia to lead another campaign in Syria against the Byzantine Empire, after which Mithna ibn Haris took command in Mesopotamia. The Persians once again concentrated armies to regain Mesopotamia, while Mithna ibn Haris withdrew from central Iraq to the region near the Arabian desert to delay war until reinforcement came from Medina. Umar sent reinforcements under the command of Abu Ubayd al-Thaqafi. This army suffered a severe defeat from the Sasanian army in 634 at the Battle of the Bridge in which Abu Ubayd was killed, and Al-Muthanna saved the army from complete disaster by heroically defending a bridge over the Euphrates.[85] The response was delayed until after a decisive Muslim victory against the Romans in the Levant at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636. Umar was then able to transfer forces to the east and resume the offensive against the Sasanians. Umar dispatched 36,000 men along with 7500 troops from the Syrian front, under the command of Sa`d ibn Abī Waqqās against the Persian army. The Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, the decisive battle of the campaign (near modern Najaf)[86] followed, with the Persians prevailing at first, but, on the third day of fighting, the Muslims gained the upper hand. The legendary Persian general Rostam Farrokhzād was killed during the battle. According to some sources, the Persian losses were 20,000, and the Arabs lost 10,500 men.

Following this Battle, the Arab Muslim armies pushed forward toward the Persian capital of Ctesiphon (also called Madā'in in Arabic), which was quickly evacuated by Yazdgird after a brief siege. After seizing the city, they continued their drive eastwards, following Yazdgird and his remaining troops as they attempted to regroup in the Zagros mountains.[86] Within a short span of time, the Arab armies defeated a major Sasanian counterattack in the Battle of Jalūlā', as well as other engagements at Qasr-e Shirin, and Masabadhan. By the mid-7th century, the Arabs controlled all of Mesopotamia, including the area that is now the Iranian province of Khuzestan. It is said that Caliph Umar did not wish to send his troops through the Zagros Mountains and onto the Iranian plateau. One tradition has it that he wished for a "wall of fire" to keep the Arabs and Persians apart. Later commentators explain this as a common-sense precaution against over-extension of his forces. The Arabs had only recently conquered large territories that still had to be garrisoned and administered. The continued existence of the Persian government was, however, incitement to revolt in the conquered territories and unlike the Byzantine army, the Sasanian army was continuously striving to regain their lost territories. Finally, Umar pressed forward, which eventually resulted in the wholesale conquest of the Sasanian Empire. Yazdegerd, the Sasanian king, made yet another effort to regroup and defeat the invaders. By 641 he had raised a new force, which made a stand at the Battle of Nihawānd, some forty miles south of Hamadan in modern Iran. The Rashidun army, under the command of Umar's appointed general Nu'man ibn Muqarrin al-Muzani, attacked and again defeated the Persian forces. The Muslims proclaimed it the Victory of Victories (Fath alfotuh), after which the Persians were unable to offer any effective resistance.[86]

Though Yazdegerd was unable to raise another army, the invading Arabs advanced slowly because "distances were great, the population hostile, and towns and fortresses had to be captured one by one".[86] Yazdegerd retreating east with a dwindling band of supporters, eventually to Khurasan where he was assassinated.[86] In 642 Umar sent the army to conquer the remainder of the Persian Empire. The entirety of present-day Iran was conquered, followed by Greater Khorasan (which included the modern Iranian Khorasan province and modern Afghanistan), Transoxania, Balochistan and Makran (part of modern-day Pakistan), Azerbaijan, Dagestan (Russia), Armenia and Georgia; these regions were later re-conquered during Uthman's reign with further expansion into the regions which were not conquered during Umar's reign; hence, the Rashidun Caliphate's frontiers in the east extended to the lower river Indus and north to the Oxus River.

Wars against the Byzantine Empire

editUnlike the Sasanian Persians, the Byzantines, after losing Syria, retreated back to Anatolia. As a result, they also lost Egypt to the invading Rashidun army, although the civil wars among the Muslims halted the war of conquest for many years, and this gave time for the Byzantine Empire to recover.

Conquest of Byzantine Syria

editAfter Khalid ibn al-Walid consolidated his control of Iraq, Abu Bakr sent four armies to Syria on the Byzantine front under four different commanders: Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah (acting as their supreme commander), Amr ibn al-As, Yazid ibn Abu Sufyan and Shurhabil ibn Hasana. However, their advance was halted by a concentration of the Byzantine army at Ajnadayn. Abu Ubaidah then sent for reinforcements. Abu Bakr ordered Khalid, who by now was planning to attack Ctesiphon, to march from Iraq to Syria with half his army. There were 2 major routes to Syria from Iraq, one passing through Mesopotamia and the other through Daumat ul-Jandal. Khalid took an unconventional route through the Syrian Desert, and after a perilous march of 5 days, appeared in north-western Syria.[citation needed]

The border forts of Sawa, Arak, Tadmur, Sukhnah, al-Qaryatayn and Hawarin were the first to fall to the invading Muslims. Khalid marched on to Bosra via the Damascus road. At Bosra, the Corps of Abu Ubaidah and Shurhabil joined Khalid, upon which, per Abu Bakr's orders, Khalid assumed overall command from Abu Ubaidah. Bosra, caught unprepared, surrendered after a brief siege in July 634 (see Battle of Bosra), effectively ending the dynasty of the Ghassanids.[citation needed]

From Bosra, Khalid sent orders to the other corps commanders to join him at Ajnadayn, where, according to early Muslim historians, a Byzantine army of 90,000 (modern sources state 9,000)[87] was concentrated to push back the Muslims. The Byzantine army was defeated decisively on 30 July 634 in the Battle of Ajnadayn. It was the first major pitched battle between the Muslims and Byzantines and cleared the way for the former to capture central Syria. Damascus, the Byzantine stronghold, was conquered shortly after on 19 September 634. The Byzantine army was given a deadline of 3 days to flee as far as they could, with their families and treasure, or simply agree to stay in Damascus and pay tribute. After the three days had passed, the Muslim cavalry, under Khalid's command, attacked the Roman army by catching up to them using an unknown shortcut at the battle of Maraj-al-Debaj.[citation needed]

On 22 August 634, Abu Bakr died, making Umar his successor. Umar replaced Khalid with Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah as overall commander of the Muslim armies,[88] though Khalid continuing play an important part in the conquests under Abu Ubaidah. The conquest of Syria slowed down under Abu Ubaidah while he relied heavily on the advice of Khalid, who he kept close at hand.[citation needed]

The last large garrison of the Byzantine army was at Fahl, which was joined by survivors of Ajnadayn. With this threat at their rear, the Muslim armies could not move further north nor south. Thus Abu Ubaidah decided to deal with the situation, and defeated and routed this garrison at the Battle of Fahl on 23 January 635, which proved to be the "Key to Palestine". After this battle Abu Ubaidah and Khalid marched north towards Emesa; Yazid was stationed in Damascus while Amr and Shurhabil marched south to capture Palestine.[88] While the Muslims were at Fahl, sensing the weak defense of Damascus, Emperor Heraclius sent an army to re-capture the city. This army, however, could not make it to Damascus and was intercepted by Abu Ubaidah and Khalid on their way to Emesa. The army was destroyed in the battle of Maraj-al-Rome and the second battle of Damascus. Emesa and the strategic town of Chalcis made peace with the Muslims for one year in order to buy time for Heraclius to prepare his defences and raise new armies. The Muslims welcomed the peace and consolidated their control over the conquered territory. However, as soon as the Muslims received the news of reinforcements being sent to Emesa and Chalcis, they marched against Emesa, laid siege to it and eventually captured the city in March 636.[89]

The prisoners taken in the battle informed them about Emperor Heraclius's plans to take back Syria. They said that an army possibly 200,000 strong would soon emerge to recapture the province. Khalid stopped here on June 636. As soon as Abu Ubaida heard the news of the advancing Byzantine army, he gathered all his officers to plan their next move. Khalid suggested that they should consolidate all of their forces present in the province of Syria (Syria, Jordan, Palestine) and then move towards the plain of Yarmouk for battle.[citation needed]

Abu Ubaida ordered the Muslim commanders to withdraw from all the conquered areas, return the tributes they had previously gathered, and move towards Yarmuk.[90] Heraclius's army also moved towards Yarmuk, but the Muslim armies reached it in early July 636, a week or two before the Byzantines.[91] Khalid's mobile guard defeated the Christian Arab auxiliaries of the Roman army in a skirmish.

In the third week of August, the Battle of Yarmouk was fought, resulting in the whole of Syria falling into Muslim hands.[36] The battle lasted 6 days during which Abu Ubaida transferred the command of the entire army to Khalid. Outnumbered five-to-one, the Muslims nevertheless defeated the Byzantine army in October 636. Abu Ubaida held a meeting with his high command officers, including Khalid, to decide on future conquests, settling on Jerusalem. The siege of Jerusalem led to great hunger[92] but it negotiated a treaty of surrender with Umar with very generous terms. Christians were promised protection, freedom of worship,[93] that churches would not be turned into mosques,[92] and a tax less heavy than what they had paid Byzantium.[93] Jerusalem surrendered in April 637 and Caliph Umar's appearance wearing a course robe made a strong impression on Jerusalemites accustom to Byzantine splendor.[93] He allowed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to remain, and prayed on a prayer rug outside of the church.[92]

Abu Ubaida sent Amr bin al-As, Yazid bin Abu Sufyan, and Sharjeel bin Hassana back to their areas to reconquer them; most submitted without a fight. Abu Ubaida himself, along with Khalid, moved to northern Syria to reconquer it with a 17,000-man army. Khalid, along with his cavalry, was sent to Hazir and Abu Ubaidah moved to the city of Qasreen.[citation needed]

Khalid defeated a strong Byzantine army at the Battle of Hazir and reached Qasreen before Abu Ubaidah. The city surrendered to Khalid, and soon after, Abu Ubaidah arrived in June 637. Abu Ubaidah then moved against Aleppo, with Khalid, as usual, commanding the cavalry. After the Battle of Aleppo the city finally agreed to surrender in October 637.[citation needed]

Occupation of Anatolia

editIn the mountains of Asia Minor, the Muslims enjoyed less success, with the Byzantines adopting the tactic of "shadowing warfare" — refusing to give battle to the Muslims, while the people retreated into castles and fortified towns when the Muslims invaded; instead, Byzantine forces ambushed Muslim raiders as they returned to Syria carrying plunder and people they had enslaved.[94]

Abu Ubaidah and Khalid ibn al-Walid, after conquering all of northern Syria, moved north towards Anatolia taking the fort of Azaz to clear the flank and rear of Byzantine troops. On their way to Antioch, a Roman army blocked them near a river on which there was an iron bridge. Because of this, the following battle is known as the Battle of the Iron Bridge. The Muslim army defeated the Byzantines and Antioch surrendered on 30 October 637 CE. Later during the year, Abu Ubaidah sent Khalid and Iyad ibn Ghanm at the head of two separate armies against the western part of Jazira, most of which was conquered without strong resistance, including parts of Anatolia, Edessa and the area up to the Ararat plain. Other columns were sent to Anatolia as far west as the Taurus Mountains, the important city of Marash, and Malatya, which were all conquered by Khalid in the autumn of 638 CE. During Uthman's reign, the Byzantines recaptured many forts in the region and on Uthman's orders, a series of campaigns were launched to regain control of them. In 647 Muawiyah, the governor of Syria, sent an expedition against Anatolia, invading Cappadocia and sacking Caesarea Mazaca. In 648 the Rashidun army raided Phrygia. A major offensive into Cilicia and Isauria in 650–651 forced the Byzantine Emperor Constans II to enter into negotiations with Muawiyah. The truce that followed allowed a short respite and made it possible for Constans II to hold on to the western portions of Armenia. In 654–655, on the orders of Uthman, an expedition prepared to attack Constantinople, but this plan was not carried out due to the civil war that broke out in 656.[citation needed]

The Muslim advance north was stopped by the barrier of the Nur Mountains.[95] The Taurus Mountains in Turkey marked the western frontiers of the Rashidun Caliphate in Anatolia during Caliph Uthman's reign. In the frontier area where Anatolia met Syria, the Byzantine state evacuated the entire population and laid waste to the countryside, creating a no man's land where any invading army would find no food.[94] For decades afterwards, a guerrilla war was waged by Christians in the hilly countryside of north-western Syria supported by the Byzantines.[96] At the same time, the Byzantines began a policy of launching raids via sea on the coast of the caliphate with the aim of forcing the Muslims to keep at least some of their forces to defend their coastlines, thus limiting the number of troops available for an invasion of Anatolia.[96] Unlike Syria with its plains and deserts — which favored the offensive — the mountainous terrain of Anatolia favored the defensive, and for centuries afterwards the line between Christian and Muslim lands ran along the border between Anatolia and Syria.[94]

Conquest of Egypt

editThe Byzantine province of Egypt held strategic importance for its grain production, naval yards, and as a base for further conquests in Africa.[97] Possessing some of the most productive and fertile farmland in the entire world, the Nile Delta made Egypt the "granary" of the Byzantine empire.[98] Control of it meant that the caliphate could weather droughts without the fear of famine.[98] In 639, Egypt was a prefecture of the Byzantine Empire, but had been occupied just a decade before by the Sasanian Empire under Khosrau II (616 to 629 CE). The power of the Byzantine Empire was shattered during the Muslim conquest of Syria, and therefore the conquest of Egypt was much easier.

The Muslim general Amr ibn al-As began the conquest of the province on his own initiative in 639.[99] The majority of the Byzantine forces in Egypt were locally raised Coptic forces, intended to serve more as a police force; since the vast majority of Egyptians lived in the Nile River valley, surrounded on both the eastern and western sides by desert, Egypt was felt to be a relatively secure province.[100]

In December 639, Amr entered the Sinai with a large force and took Pelusium, on the edge of the Nile River valley, and then defeated a Byzantine counter-attack at Bibays.[98]

Contrary to expectations, the Arabs did not head for Alexandria, the capital of Egypt, but instead for a major fortress known as Babylon located at what is now Cairo.[100] They advanced rapidly into the Nile Delta. The imperial garrisons retreated into the walled towns, where they successfully held out for a year or more. Amr was planning to divide the Nile River valley in two.[98] The Arab forces won a major victory at the Battle of Heliopolis in 640, cleverly luring Byzantine forces away from the Babylon Fortress.[95]

However Amr found it difficult to advance further because major cities in the Nile Delta were protected by water and because Amr lacked the machinery to break down city fortifications.[101]

Amr next proceeded in the direction of Alexandria, which was surrendered to him by a treaty signed on 8 November 641. The Thebaid seems to have surrendered with scarcely any opposition.

The ease with which this valuable province was wrenched from the Byzantine Empire is said to have been due to the treachery of Cyrus,[102] prefect of Egypt and Patriarch of Alexandria, and the incompetence of the Byzantine generals, as well as the loss of most of the Byzantine troops in Syria. Cyrus had persecuted the local Coptic Christians. He was one of the authors of monothelism, a 7th-century heresy, and some supposed him to have been a secret convert to Islam.

In 645, during Uthman's reign, the Byzantines briefly regained Alexandria, but it was retaken by Amr in 646. In 654 an invasion fleet sent by Constans II was repulsed. After this, no serious effort was made by the Byzantines to regain possession of the country.

The Muslims were assisted by some Copts, who found the Muslims more tolerant than the Byzantines, and of these, some turned to Islam. In return for a tribute of money and food for the occupation troops, the Christian inhabitants of Egypt were excused from military service and left free in the observance of their religion and the administration of their affairs. Others sided with the Byzantines, hoping that they would provide a defense against the Arab invaders.[103] During the reign of Caliph Ali, Egypt was captured by rebel troops under the command of former Rashidun army general Amr ibn al-As, who killed Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, the governor of Egypt appointed by Ali.

Conquest of the Maghreb

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

After the withdrawal of the Byzantines from Egypt, the Exarchate of Africa (i.e. that part of Byzantine North Africa west of Egypt), under its exarch (governor), Gregory the Patrician declared its independence. Abdullah ibn Sa'ad sent raiding parties to the west, resulting in considerable booty and encouraging Sa'ad to propose a campaign to conquer the Exarchate, which Uthman approved. A force of 10,000 soldiers was sent as reinforcement. The Rashidun army assembled in Barqa in Cyrenaica, and from there marched west, first capturing Tripoli, and then Sufetula, Gregory's capital. In the ensuing battle (647 CE), the Exarchate was defeated and Gregory was killed due to the superior tactics of Abdullah ibn Zubayr. Afterward, the people of North Africa sued for peace, agreeing to pay an annual tribute. Instead of annexing North Africa, the Muslims preferred to make North Africa a vassal state, fearing a counter offensive.[95] When the stipulated amount of the tribute was paid, the Muslim forces withdrew to Barqa. Following the First Fitna, the first Islamic civil war, Muslim forces withdrew from north Africa to Egypt. The Umayyad Caliphate would later re-invade North Africa in 664.

Campaign against Nubia (Sudan)

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

A campaign was undertaken against Nubia during the Caliphate of Umar in 642, but failed after the Makurians won the First Battle of Dongola. The Muslim army pulled out of Nubia with nothing to show for it. Ten years later, Uthman's governor of Egypt, Abdullah ibn Saad, sent another army to Nubia. This army penetrated deeper into Nubia and laid siege to the Nubian capital of Dongola. The Muslims damaged the cathedral in the center of the city, but Makuria also won this battle. As the Muslims were unable to overpower Makuria, they negotiated a mutual non-aggression treaty with their king, Qalidurut. Each side also agreed to afford free passage to each other through their respective territories. Nubia agreed to provide 360 slaves to Egypt every year, while Egypt agreed to supply grain, horses, and textiles to Nubia according to demand.

Conquest of the islands of the Mediterranean Sea

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

During Umar's reign, the governor of Syria, Muawiyah I, sent a request to build a naval force to invade the islands of the Mediterranean Sea but Umar rejected the proposal because of the risk to the soldiers. Once Uthman became caliph, however, he approved Muawiyah's request. In 650, Muawiyah attacked Cyprus, conquering the capital, Constantia, after a brief siege, but signed a treaty with the local rulers. During this expedition, a relative of Muhammad, Umm-Haram, fell from her mule near the Salt Lake at Larnaca and was killed. She was buried in that same spot, which became a holy site for many local Muslims and Christians and, in 1816, the Hala Sultan Tekke was built there by the Ottomans. After apprehending a breach of the treaty, the Arabs re-invaded the island in 654 CE with five hundred ships. This time, however, a garrison of 12,000 men was left in Cyprus, bringing the island under Muslim influence.[104] After leaving Cyprus, the Muslim fleet headed towards Crete and then Rhodes and conquered them without much resistance. From 652 to 654, the Muslims launched a naval campaign against Sicily and captured a large part of the island. Soon after this, Uthman was murdered, ending his expansionist policy, and the Muslims accordingly retreated from Sicily. In 655 Byzantine Emperor Constans II led a fleet in person to attack the Muslims at Phoinike (off Lycia) but it was defeated: both sides suffered heavy losses in the battle, and the emperor himself narrowly avoided death.

Rashidun military

editThe Rashidun military was the primary arm of the Islamic armed forces of the 7th century, serving alongside the Rashidun navy. The army maintained a very high level of discipline, strategic prowess, and organization, along with the motivation and initiative of the officer corps. For much of its history, this army was one of the most powerful and effective military forces throughout the region. At the height of the Rashidun Caliphate, the maximum size of the army was around 100,000 troops.[105]

Army

editThe Rashidun army was divided into infantry and light cavalry. Reconstructing the military equipment of early Muslim armies is problematic. Compared with Roman armies or later medieval Muslim armies, the range of visual representation is very small, often imprecise. Physically, very little material evidence has survived, and much of it is difficult to date.[106] The soldiers wore iron and bronze segmented helmets from Iraq, of Central Asian type.[107]

The standard form of body armor was chainmail. There are also references to the practice of wearing two coats of mail (dir’ayn), the one under the main one being shorter or even made of fabric or leather. Hauberks and large wooden or wickerwork shields were also used as protection in combat.[106] The soldiers were usually equipped with swords hung in a baldric. They also possessed spears and daggers.[108][page needed] Umar was the first Muslim ruler to organize the army as a state department, in 637. A beginning was made with the Quraysh and the Ansar and the system was gradually extended to the whole of Arabia and to Muslims of conquered lands.[citation needed]

The basic strategy of early Muslim armies on the campaign was to exploit every possible weakness of the enemy. Their key strength was mobility. The cavalry had both horses and camels, the latter used as both transport and food for long marches through the desert (e.g., Khalid ibn al-Walid's extraordinary march from the Persian border to Damascus). The cavalry was the army's main strike force and also served as a strategic mobile reserve. The common tactic was to use the infantry and archers to engage and maintain contact with the enemy while the cavalry was held back till the enemy was fully engaged. Once fully engaged, the enemy reserves were held by the infantry and archers, while the cavalry executed a pincer movement (like modern tank and mechanized divisions) to attack the enemy from the sides or to assault their base camps.[citation needed]

The Rashidun army was, in quality and strength, below the standard set by the Sasanian and Byzantine armies. Khalid ibn al-Walid was the first general of the Rashidun Caliphate to successfully conquer foreign lands. During his campaign against the Sasanian Empire (Iraq, 633–634) and the Byzantine Empire (Syria, 634–638), Khalid developed brilliant tactics that he used effectively against both enemy armies.[citation needed]

Abu Bakr's strategy was to give his generals their mission, the geographical area in which that mission would be carried out, and resources for that purpose. He would then leave it to his generals to accomplish their missions in whatever manner they chose. On the other hand, Umar, in the latter part of his Caliphate, adopted a more hands-on approach, directing his generals where to stay and when to move to the next target and who was to command the left and right-wing of the army in each particular battle. This made conquests comparatively slower but made the campaigns well-organized. Uthman and Ali reverted to Abu Bakr's method, giving missions to their generals and leaving the details to them.[citation needed]

Rashidun navy

editThe early caliphate naval conquest managed to mark long time legacy of Islamic maritime enterprises from the Conquest of Cyprus, the famous Battle of the Masts[109] up to of their successor states such as the area Transoxiana from area located in between the Jihun River (Oxus/Amu Darya) and Syr Darya, to Sindh (present day Pakistan), by Umayyad,[110] naval cove of privateer in La Garde-Freinet by Cordoban Emirate,[111] and the Sack of Rome by the Aghlabids in later era.[112][113][114]

Governance

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

The conquests begun under caliphs Abu Baker and expanded under Umar resulted in an empire of vast size, covering a diversity of races, customs, types of government.

Caliph Umar allowed the local administration of occupied countries to carry on much as before, (according to scholar Laura Veccia Vaglieri), [32] and confined himself to appointing a commander or governor (amir) with full powers, sometimes assisted by an agent (amil), responsible directly to the capital's empire in Medina, to take care of financial matters. He then kept a "tight rein" on these officials.[32]

During his reign, Abu Bakr established the Bayt al-Mal (state treasury). Umar expanded the treasury and established a government building to administer the state finances.[115]

Treatment of conquered peoples

editThe conquered people of the caliphate (the vast majority of the population) were non-Muslim. Those who were monotheists—Jews, Zoroastrians, and Christians—in conquered lands were called dhimmis (the protected people). Dhimmis were allowed to "practice their religion, and to enjoy a measure of communal autonomy" and were guaranteed their personal safety and security of property, but only in return for paying tax (jizya)[116] and acknowledging Muslim rule.[117]

The Rashidun caliphs had placed special emphasis on relatively fair and just treatment of the dhimmis, which were also provided 'protection' by the Caliphate and were not expected to fight as Muslims were. Sometimes, particularly when there were not enough qualified Muslims, dhimmis were allowed to hold important positions in the government. In the following decades Islamic jurists elaborated a legal framework in which other religions would have a protected but subordinate status.[118] Islamic law followed the Byzantine precedent of classifying subjects of the state according to their religion, in contrast to the Sasanian model which put more weight on social than on religious distinctions.[119] In theory, only monotheists could be dhimmi and severe restrictions were placed on paganism, as the Byzantine empire had. But in practice most non-Abrahamic communities of the former Sasanian territories were classified as possessors of a scripture (ahl al-kitab) and granted protected (dhimmi) status.[119]

Conquered land

editAccording to Islamic law, Muslim conquerors may do as they wish with the property of non-Muslims who did not surrender before being conquered, (enemy who surrendered under terms of a treaty were generally allowed to keep their land),[32] and many Muslims called for Umar to distributed the land of the conquered as spoils among the Arabs (according to a pious work by Abdus Salam Nadvi based on Muslim literature).[120]

Instead, Umar allowed the non-Muslims landowners to keep their land and set up a system of taxation of land.[120] (Nadvi attributing this to Umar's benevolence, and non-Muslim scholar Laura Vaglieri to Umar's good sense -- the conquering rank and file who the land might have been divided among being Bedouin, who knew herding and raiding but not the cultivation skills of peasantry.)[32]

Districts or provinces

editUnder Abu Bakr, the empire was not clearly divided into provinces, though it had many administrative districts.

Under Umar the Empire was divided into a number of provinces which were as follows:

- Arabia was divided into two provinces, Mecca and Medina.

- Iraq was divided into two provinces, Basra and Kufa.

- Jazira was divided into two provinces, the Tigris and the Euphrates.

- Syria was a province.

- Palestine was divided in two provinces: Aylya and Ramlah.

- Egypt was divided into two provinces: Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt.

- Persia was divided into three provinces: Khorasan, Azerbaijan, and Fars.

In his testament Umar had instructed his successor, Uthman, not to make any change in the administrative setup for one year after his death, which Uthman honored; however, after the expiration of the moratorium, he made Egypt one province and created a new province comprising North Africa.[citation needed]

During Uthman's reign the caliphate was divided into 12 provinces. These were:

During Ali's reign, with the exception of Syria (which was under Muawiyah I's control) and Egypt (lost during the latter years of his caliphate to the rebel troops of Amr ibn Al-A'as), the remaining ten provinces were under his control, with no change in administrative organization.

The provinces were further divided into districts. Each of the 100 or more districts of the empire, along with the main cities, were administered by a governor (Wāli). Other officers at the provincial level were:

- Katib, the Chief Secretary.

- Katib-ud-Diwan, the Military Secretary.

- Sahib-ul-Kharaj, the Revenue Collector.

- Sahib-ul-Ahdath, the Police Chief.

- Sahib-ul-Bait-ul-Mal, the Treasury Officer.

- Qadi, the Chief Judge.

In some districts there were separate military officers, though the governor was in most cases the commander-in-chief of the army quartered in the province.

The officers were appointed by the Caliph. Every appointment was made in writing. At the time of appointment, an instrument of instructions was issued to regulate the conduct of the governors. On assuming office, the Governor was required to assemble the people in the main mosque, and read the instrument of instructions before them.[121]

Umar's general instructions to his officers were:

Remember, I have not appointed you as commanders and tyrants over the people. I have sent you as leaders instead, so that the people may follow your example. Give the Muslims their rights and do not beat them lest they become abused. Do not praise them unduly, lest they fall into the error of conceit. Do not keep your doors shut in their faces, lest the more powerful of them eat up the weaker ones. And do not behave as if you were superior to them, for that is tyranny over them.

During the reign of Abu Bakr the state was economically weak, while during Umar's reign because of an increase in revenues and other sources of income, the state was on its way to economic prosperity. Hence Umar felt it necessary to treat the officers strictly, in order to prevent corruption. During his reign, at the time of appointment, every officer was required to swear an oath:

- That he would not ride a Turkic horse (which was a symbol of pride).

- That he would not wear fine clothes.

- That he would not eat sifted flour.

- That he would not keep a porter at his door.

- That he would always keep his door open to the public.

Caliph Umar himself followed the above postulates strictly. During the reign of Uthman the state became more economically prosperous than ever before; the allowance of the citizens was increased by 25%, and the economic condition of the ordinary person was more stable, which led Caliph Uthman to revoke the second and third postulates of the oath.

At the time of an officer's appointment, a complete inventory of all his possessions was prepared and kept on record. If there was later an unusual increase in his possessions, he was immediately called to account, and the unlawful property confiscated by the State. The principal officers were required to come to Mecca on the occasion of the Hajj, during which people were free to present any complaint against them. In order to minimize the chances of corruption, Umar made it a point to pay high salaries to the staff. Provincial governors received as much as five to seven thousand dirhams annually besides their share of the spoils of war (if they were also the commander-in-chief of the army of their sector).

Judicial administration

editThe judicial administration, like the rest of the administrative structure of the Rashidun Caliphate, was set up by Umar, and it remained basically unchanged throughout the duration of the Caliphate. In order to provide adequate and speedy justice for the people, justice was administered according to the principles of Islam.[citation needed]

Accordingly, Qadis (judges) were appointed at all administrative levels. The Qadis were chosen for their integrity and learning in Islamic law. Wealthy men and men of high social status, compensated highly by the Caliphate, were appointed in order to make them resistant to bribery or undue influence based on social position. The Qadis also were not allowed to engage in trade. Judges were appointed in sufficient numbers to staff every district with at least one.[citation needed]

Electing or appointing a caliph

editWith the exception of Umar who was appointed by Abu Bakr, the Rashidun caliphs were chosen by a small group of prominent members of the Quraysh tribe called shūrā (Arabic: شُـوْرَى, lit. 'consultation').[122]

Fred Donner, in his book The Early Islamic Conquests (1981), argues that the standard Arabian practice during the early Caliphates was for the prominent men of a kinship group, or tribe, to gather after a leader's death and elect a leader from amongst themselves, although there was no specified procedure for this shura, or consultative assembly. Candidates were usually from the same lineage as the deceased leader, but they were not necessarily his sons. Capable men who would lead well were preferred over an ineffectual direct heir, as there was no basis in the majority Sunni view that the head of state or governor should be chosen based on lineage alone.

Abu Bakr Al-Baqillani has said that the leader of the Muslims should simply be from the majority. Abu Hanifa an-Nu‘man also wrote that the leader must come from the majority.[123]

Sunni belief

editFollowing the death of Muhammad, a meeting took place at Saqifah. At that meeting, Abu Bakr was elected caliph by the Muslim community. Sunni Muslims developed the belief that the caliph is a temporal political ruler, appointed to rule within the bounds of Islamic law (viz., the rules of life set by Allah in the Qur'an). The job of adjudicating orthodoxy and Islamic law was left to Islamic lawyers, judiciary, or specialists individually termed as Mujtahids and collectively named the Ulema. The first four caliphs are called the Rashidun, meaning the Rightly Guided Caliphs, because they are believed to have followed the Qur'an and the sunnah (example) of Muhammad in all things.[citation needed]

Accountability of rulers

editSunni Islamic lawyers have commented on when it is permissible to disobey, impeach or remove rulers in the Caliphate. This is usually when the rulers are not meeting public responsibilities obliged upon them under Islam.

Al-Mawardi said that if the rulers meet their Islamic responsibilities to the public, the people must obey their laws, but if they become either unjust or severely ineffective then the Caliph or ruler must be impeached via the Majlis al-Shura. Al-Juwayni argued that Islam is the goal of the ummah, so any ruler that deviates from this goal must be impeached. Al-Ghazali believed that oppression by a caliph is enough for impeachment. Rather than just relying on impeachment, Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani obliged rebellion upon the people if the caliph began to act with no regard for Islamic law. Al-Asqalani said that to ignore such a situation is haraam, and those who cannot revolt inside the caliphate should launch a struggle from outside. He used two ayahs from the Qur'an to justify this:

And they (the sinners on qiyama) will say, "Our Lord! We obeyed our leaders and our chiefs, and they misled us from the right path. Our Lord! Give them (the leaders) double the punishment you give us and curse them with a very great curse"...[33:67–68]

Islamic lawyers have commented that when the rulers refuse to step down via successful impeachment through the Majlis, becoming dictators through the support of a corrupt army, the majority, upon agreement, has the option to launch a revolution against them. Many noted that this option is only exercised after factoring in the potential cost of life.[123]

Economy

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

According to a pious work on early Islam by Abdus Salam Nadvi, among their other virtues, the Rashidun were known for their leniency in levying taxation.[124]

Bait-ul-Maal

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

Bait-ul-Maal (lit., the house of money) aka treasury aka state exchequer, was established by Abu Bakr. Umar built the building housing it.[115]

Revenues for the Bait came from taxes on lands left in the hands of their owners, rents from confiscated lands, and to a lesser extent zakat tithe paid by Muslims, one fifth the value of booty, and tribute and personal taxes paid by the conquered.[125]

A "major portion" of the funds collected for the Bait-ul-Maal (at least under caliph Umar) went to stipends or allowances that Muslims gave themselves[126] as conquerors of the land.

After consulting the Companions, Umar decided to establish the central Treasury at Medina. Abdullah bin Arqam was appointed as the Treasury Officer. He was assisted by Abdur Rahman bin Awf and Muiqib. A separate Accounts Department was also set up to maintain spending records. Later treasuries were set up in the provinces. After meeting the local expenditure the provincial treasuries were required to remit the surplus revenue to the central treasury at Medina. According to Yaqubi the salaries and stipends charged to the central treasury amounted to over 30 million dirhams.

A separate building was constructed for the royal treasury, the bait ul maal, which, in large cities, was protected by as many as 400 guards.

Most historical accounts state that, among the Rashidun caliphs, Uthman was the first to strike coins; some accounts, however, state that Umar was the first to do so. When Persia was conquered, three types of coins were current there: the Baghli, of eight dang; Tabari of four dang; and Maghribi of three dang. Umar (or Uthman, according to some accounts) first struck an Islamic dirham of six dang.

Social welfare and pensions were introduced in early Islamic law as forms of zakāt (charity), one of the Five Pillars of Islam, since the time of Umar. The taxes (including zakāt and jizya) collected in the treasury of an Islamic government were used to provide income for the needy, including the poor, elderly, orphans, widows, and the disabled. According to the Islamic jurist Al-Ghazali (Algazel, 1058–1111), the government was also expected to stockpile food supplies in every region in case a disaster or famine occurred.[128] Many Muslim thus argue the Rashidun caliphate was thus one of the earliest welfare states.[129]

Taxation

editA "regular system of revenue" for Iraq was set up during Umar's caliphate. According to Abdus Salam Nadvi, Umar chose to set up a system of taxation of the current (non-Muslim) owners of land of the conquered people instead of distributing the land as spoils among the conquering Arabs.[120]

Among other benevolences reported in Muslim literature, the Rashidun were said to be lenient in their tax collection. He appointed capable Companions of the Prophet to organize an assessment of arable/taxable land, confiscating only land from pagan temples, "absconders and the rebellious", and some others, and set taxes according to crops raised on the land,[130] giving the taxpayer the choice of several tax collectors to collect their taxes. In doing all this he sought advise from "venerable persons" for improvement of his work, including non-Muslims Zimmi subject.[131] Outside of Iraq he forbade extra confiscation of crops above the rate of tribute taxation and forbade Muslims (who received stipends) from taking possession of the conquered people's land, threatening or punishing those who did.[132] He also confiscated land from those who did not cultivate it.[133]

Caliph Ali reportedly advised a newly appointed tax collector:

"Do not beat with while receiving revenue from any person. Do not take their livelihood, summer and winter garments and beasts of burden. Neither cause anyone stand".[134]

The economic resources of the State were:

- Zakāt

- Ushr

- Jizya

- Fay

- Khums

- Kharaj

Zakat

editZakāt tax on Muslims to give to the poor (usually amounting to 2.5% of dormant wealth over a certain amount). The Rashidun reportedly complied with the practice of Muhammad of not taking the best goods of the taxpayers by way of Zakat.[135]

Jizya

editJizya was a per capita tax imposed on able bodied (disabled were exempt) non-Muslim men (known as Zimmis). Nadvi states that collectors were forbidden from torturing the Zimmis while collecting Jizyah.[134]

Fay

editFay was the income from State land, whether an agricultural land or a meadow or land with any natural mineral reserves.

Khums

editGhanimah or Khums represented war booty, four-fifths of which was distributed among serving soldiers, while one-fifth was allotted to the state.

Kharaj

editKharaj was a tax on agricultural land.

Initially, after the first Muslim conquests in the 7th century, kharaj usually denoted a lump-sum duty levied upon the conquered provinces and collected by the officials of the former Byzantine and Sasanian empires, or, more broadly, any kind of tax levied by Muslim conquerors on their non-Muslim subjects, dhimmis. At that time, kharaj was synonymous with jizyah, which later emerged as a poll tax paid by dhimmis. Muslim landowners, on the other hand, paid only ushr, a religious tithe, which carried a much lower rate of taxation.[136]

Ushr

editUshr was a reciprocal 10% levy on agricultural land as well as merchandise imported from states that taxed the Muslims on their products. Umar was the first Muslim ruler to levy ushr. Umar issued instructions that ushr should be levied in such a way so as to avoid hardship, so as not to affect trade within the Caliphate. The tax was levied only on merchandise meant for sale; goods imported for consumption or personal use but not for sale were not taxed. Merchandise valued at 200 dirhams or less was not taxed. Imports by citizens for trade purposes were subject to the customs duty or import tax at lower rates. In the case of the dhimmis, the rate was 5% and, in the case of the Muslims, 2.5%, the same as that of zakāt. The levy was thus regarded as a part of zakāt rather than a separate tax.

Distribution of spoils

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

Beginning of the allowance

editAfter the Battle of the Yarmuk and Battle of al-Qadisiyyah the Muslims won heavy spoils, filling the coffers at Medina. The problem before Umar was what to do with this money. Someone suggested that the money should be kept in the treasury as a reserve for public expenditures. However, this view was not acceptable to the general body of Muslims. Accordingly, a consensus was reached to distribute whatever was received during a year to the citizens as "allowances" (aka pensions), the register of which was called the dīwān.[125]

The next question was what system should be adopted for distribution. One suggestion was to distribute it equally on an ad hoc basis. Others objected that, as the spoils were considerable, the proposal would make the people very rich. It was therefore agreed that, instead of ad hoc division, the amount of the allowance to the stipend should be determined beforehand and this allowance should be paid regardless of the amount of the spoils.

On the amount of the allowance there were two opinions. Some held that it should be the same for all Muslims. Umar, on the other hand, believed that the allowance should be graduated according to one's merit with reference to Islam.

Then the question arose as to what basis should be used for placing some above others. Some suggested that the Caliph should first get the highest allowance, with the remaining allowances graduating downward from that. Umar rejected the proposal and decided to start with the clan of Muhammad.

Umar set up a committee to compile a list of persons by nearness to Muhammad. The committee produced the list clan-wise. Bani Hashim appeared as the first clan, then the clan of Abu Bakr, and then the clan of Umar. Umar accepted the first two placements but relegated his clan lower on the relationship scale.

The main provisions of the final scale of allowance approved by Umar were:[citation needed]

- The widows of Muhammad received 12,000 dirhams each;

- 'Abbas ibn 'Abd al-Muttalib, the uncle of Muhammad, received an annual allowance of 7,000 dirhams;

- The grandsons of Muhammad, Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali received 5,000 dirhams each;

- Those who had become Muslims by the time of the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah got 4,000 dirhams each;

- The veterans of the Apostasy wars received 3,000 dirhams each;}}

Under this scale, Umar's son Abdullah ibn Umar received an allowance of 3,000 dirhams, while Usama ibn Zaid got 4,000. The ordinary Muslim citizens were given allowances of between 2,000 and 2,500. The regular annual allowance was given only to the urban population because they formed the backbone of the state's economic resources. The Bedouin living in the desert, cut off from the state's affairs, and making no contributions to development, were nevertheless often given stipends. On assuming office, Uthman increased these stipends by 25%.[citation needed]

| Classes of Muslim beneficiaries | Durhams per annum received |

|---|---|

| Participants of Battle of Badr | 5000 |

| Muhajireen of Habsh and participants of Battle of Uhud | 4000 |

| Muhajireen before Conquest of Mecca | 3000 |

| Those who embraced Islam after the Conquest of Mecca | 2000 |

| Participants of the Battles of Qadisiyyah and Yarmuk | 2000 |

| Inhabitants of Yemen | 4000 |

| Soldiers after the Battles of Qadisiyyah and Yarmuk | 3000 |

| Without any distinction of status | 2000 |

Public works

editUpon conquest, in almost all cases, the caliphs were burdened with the maintenance and construction of roads and bridges in return for the conquered nation's political loyalty.[138]

Some information about life under the Rashidun comes from The Ways of the Sahbah by Maulana Abdus Salam Nadvi, a pious work that according to a vender's blurb "depicts the life sketches and heroic deeds of the companions" and provides both an Historical document and "a source of inspiration for Muslims". Since the era of the companions coincides with that of the Rashidun (in addition to some decades after), the book is a source for not only (traditional claims of) the many virtues of the companions (humility, forbearance, justice, piety, fortitude, etc.) but also taxation and revenue, social welfare, public works, city populations, rights of slaves, etc. under the Rashidun.[139]

Civil welfare in Islam started in the form of the construction and purchase of wells. During the caliphate, the Muslims repaired many of the aging wells in the lands they conquered.[140]

In addition to wells, the Muslims built many tanks and canals. Many canals were purchased, and new ones constructed. While some canals were excluded for the use of monks (such as a spring purchased by Talhah), and the needy, most canals were open to general public use. Some canals were constructed between settlements, such as the Saad canal that provided water to Anbar, and the Abi Musa Canal to provide water to Basra.[141]

During a famine, Umar ibn al-Khattab ordered the construction of a canal in Egypt connecting the Nile with the sea. The purpose of the canal was to facilitate the transport of grain to Arabia through a sea-route, hitherto transported only by land. The canal was constructed within a year by 'Amr ibn al-'As, and Abdus Salam Nadiv writes that "Arabia was rid of famine for all the times to come."[142]

After four floods hit Mecca after Muhammad's death, Umar ordered the construction of two dams to protect the Kaaba. He also constructed a dam near Medina to protect its fountains from flooding.[138]

Settlements

editThe area of Basra was very sparsely populated when it was conquered by the Muslims. During the reign of Umar, the Muslim army found it a suitable place to construct a base. Later the area was settled and a mosque was erected.[143][144][145]

Upon the conquest of Madyan, it was settled by Muslims. However, soon the environment was considered harsh, and Umar ordered the resettlement of the 40,000 settlers to Kufa. The new buildings were constructed from mud bricks instead of reeds, a material that was popular in the region, but caught fire easily.

During the conquest of Egypt the area of Fustat was used by the Muslim army as a base. Upon the conquest of Alexandria, the Muslims returned and settled in the same area. Initially the land was primarily used for pasture, but later buildings were constructed.[146]

Other already populated areas were greatly expanded. At Mosul, Arfaja al-Bariqi, at the command of Umar, constructed a fort, a few churches, a mosque and a locality for the Jewish population.[147]

Miracles

editAccording to a work by al-Suyuti (in his History of the Caliphs (Tarikh al-Khulafa), Umar performed several miracles according to different hadith. One series of hadith describe how Umar interrupted a khutbah (Friday prayer sermon) to call out "'Sariyah, the mountain!’, to the confusion of his listeners who saw no Sariyah. It later turned out that Sariyah was a commander of an army Umar had sent to fight, and which at that moment was losing its battle. Though a long distance away, Sariya heard Umar's cry and realized he must position his army with its rear to a close by mountain, whereupon Sariya was victorious over the enemy. In another series of hadith Umar told a stranger he met to 'Go to your family for they have been burnt', which the man did and found they had been victims of a fire; and on another occasion Umar was able to detect whenever a lie is being told to him.

Amr ibn al-As, a military commander and governor who served under the Rashidun, learned of an Egyptian tradition where a virgin was sacrificed by being drown in the Nile river at the beginning of the year, 'without which [the Nile] does not flow'. Al-As forbade this as unIslamic, but after the human sacrifice stopped, the river stopped flowing, seeming to prove the tradition right. In answer to the Egyptians fears of famine, Al-As gave them a slip of paper to throw in the river upon which a request was written for Allah to make the river flow. The day after the paper was thrown, the river rose sixteen cubits.[148]

Significance and legacy

editNotable features