Qanun (Persian: قانون, lit. 'Law') was a monthly newspaper which was published in London during the period 1890–1898. The founder and editor of the paper was Mirza Malkam Khan who served as the Qajar Iran's envoy to Britain and Italy. It is known to be the first oppositional publication of Iran[1] and was one of the publications which improved the political awareness of Iranians.[2]

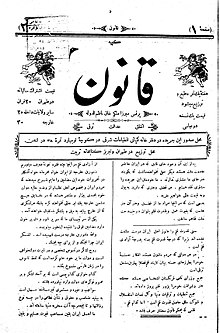

Cover page of Qanun | |

| Type | Monthly newspaper |

|---|---|

| Owner(s) | Mirza Malkam Khan |

| Founder(s) | Mirza Malkam Khan |

| Publisher | Mirza Malkam Khan |

| Editor-in-chief | Mirza Malkam Khan |

| Founded | 20 February 1890 |

| Political alignment | Constitutionalist |

| Language | Persian |

| Ceased publication | 1898 |

| Headquarters | London |

| Country | Great Britain |

History and profile

editQanun was established by Mirza Malkam Khan in 1890, and the first issue appeared on 20 February 1890.[1][3][4] Although Mirza Malkam Khan had been the envoy of Qajar Empire to London, at some point he became an ardent critic of Nasreddine Shah and started Qanun to attack him.[1] Before his establishment of the paper Mirza Malkam Khan had been fired by the Shah from the post, but he did not return to Iran and stayed in London.[5][6] The predecessor of Qanun was Mirza Malkam Khan's work entitled Daftar-i Qanun (1860; Persian: Manual of Law).[7] Initial audience of Qanun was the members of a defunct secret society established by Mirza Malkam Khan in Tehran in 1858.[8] The paper was published in a simple format and employed a plain version of Persian language.[9] Between its start in 1890 and 1892 Qanun was published on a monthly basis.[1][10]

Although the paper was banned in Iran because of its bitter criticism against the Qajar rule[9][11] it was clandestinely circulated there.[1] However, its readers were arrested and punished when they were found to possess the paper.[9] On the other hand, Qanun enjoyed popularity among Iranians living in various cities, including Istanbul, Nizir, Zanjan and Sarjan.[10] The paper was first circulated in Istanbul shortly after its start in 1890.[12]

In 1898 Mirza Malkam Khan was appointed the envoy of Qajar Iran to Italy and stopped the publication of Qanun after producing forty-two issues.[1][13] The issues of Qanun are archived by the Cambridge University Library.[14]

Content and political stance

editMirza Malkam Khan collaborated with two Qajar opponents, namely Jamal Al Din Al Afghani and Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani, in his attacks against the Qajar rule in Qanun.[15] Of them the former was a pan-Arabist and the latter was based in Istanbul.[15] The paper also attacked Nasreddine Shah's Prime Minister Amin Al Sultan.[10][16] In addition, the paper harshly criticized policies of the Qajar administration such as the tobacco concession dated 1890.[15] It frequently contained articles supporting a constitutional and fair rule in Iran.[1][13] In this regard Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamit's regime was given as a potential model for Iran.[17] The paper often praised Abdulhamit in other points, too.[12]

Mirza Malkam Khan also published articles on the religion of humanity in an attempt to introduce Western ideas to Iranians in regard to religious matters.[14] However, the paper supported Islamic unity,[17][12] and each issue of the paper began with a prayer in Arabic and ended with a religious note stating that readers forgave the news and writings if they were erroneous or contrary to the premises of Islam.[3]

Although Qanun contained secular and progressive articles, there was no specific reference to women-related issues and their rights.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Hossein Shahidi (December 2008). "Iranian Journalism and the Law in the Twentieth Century". Iranian Studies. 41 (5): 739–754. doi:10.1080/00210860802518376. S2CID 159664060.

- ^ Mehrdad Kia (1998). "Persian nationalism and the campaign for language purification". Middle Eastern Studies. 34 (2): 16–17. doi:10.1080/00263209808701220.

- ^ a b Edward Granville Browne (1966). The Persian Revolution of 1905-1909. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 35–36, 464. ISBN 978-0-7222-2499-1.

- ^ Negin Nabavi (2005). "Spreading the Word: Iran's First Constitutional Press and the Shaping of a 'New Era'". Middle East Critique. 14 (3): 309. doi:10.1080/10669920500280656. S2CID 144228247.

- ^ Homa Katouzian (2021). "The Revolution for Law: A Chronographic Analysis of the Constitutional Revolution of Iran". International Journal of Economics and Politics. 2 (1): 66. doi:10.29252/jep.2.1.63.

- ^ a b Parvin Paidar (1997). Women and the Political Process in Twentieth-Century Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-521-59572-8.

- ^ Abbas Amanat (1997). Pivot of the Universe: Nasir al-Din Shah and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831-1896. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-520-08321-9.

- ^ Hamid Algar (October 1970). "An Introduction to the History of Freemasonry in Iran". Middle Eastern Studies. 6 (3): 281. doi:10.1080/00263207008700153.

- ^ a b c Ali Asghar Kia (1996). A review of journalism in Iran: the functions of the press and traditional communication channels in the Constitutional Revolution of Iran (PhD thesis). University of Wollongong. pp. 167–168.

- ^ a b c Shiva Balaghi (2013). "Constitutionalism and Islamic Law in Nineteenth Century Iran: Mirza Malkam Khan and Qanun". In András Sajó (ed.). Human Rights with Modesty: The Problem of Universalism. Leiden: Springer. pp. 332, 336, 344. ISBN 978-94-017-6172-7.

- ^ Gholam Hossein Razi (Autumn 1968). "The Press and Political Institutions of Iran: A Content Analysis of "Ettela'at" and "Keyhan"". The Middle East Journal. 22 (4): 463–474. JSTOR 4324340.

- ^ a b c Mehrdad Kia (January 1996). "Pan-Islamism in Late Nineteenth-Century Iran". Middle Eastern Studies. 32 (1): 36–38. doi:10.1080/00263209608701090.

- ^ a b Peter Avery (1991). "Printing, the press and literature in modern Iran". In Peter Avery; et al. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 832. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521200950.023. ISBN 9781139054997.

- ^ a b Nikki R. Keddie (2013). Iran: Religion, Politics and Society: Collected Essays. Abingdon; New York: Frank Cass. pp. 24–25, 49. ISBN 978-1-136-28034-4.

- ^ a b c Camron Michael Amin (2015). "The Press and Public Diplomacy in Iran, 1820–1940". Iranian Studies. 48 (2): 273. doi:10.1080/00210862.2013.871145. S2CID 144328080.

- ^ Amir H. Ferdows (1967). The origins and development of the Persian constitutional movement (PhD thesis). Indiana University. p. 89. ISBN 9781085446808. ProQuest 302266220.

- ^ a b Afshin Matin-Asgari (2018). Both Eastern and Western: An Intellectual History of Iranian Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-108-42853-8.

External links

edit- Media related to Qanun (London newspaper) at Wikimedia Commons