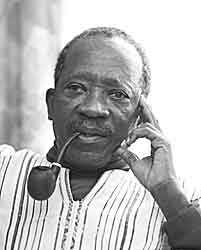

Ousmane Sembène (French: [usman sɑ̃bɛn]; 1 January 1923 or 8 January 1923[1] – 9 June 2007), was a Senegalese film director, producer and writer. The Los Angeles Times considered him one of the greatest authors of Africa and he has often been called the "father of African film".[2]

Ousmane Sembène | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 January 1923 Ziguinchor, Casamance, French West Africa |

| Died | 9 June 2007 (aged 84) Dakar, Senegal |

| Occupation | Film director, producer, screenwriter, actor & author |

| Language | Wolof, French |

| Nationality | Senegalese |

| Years active | 1956–2003 |

| Notable works | Borom Sarret (1963)

Black Girl (1966) Mandabi (1968) |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

He was often credited for his work in the French style as Sembène Ousmane, which he seemed to favor as a way to underscore the "colonial imposition" of this naming ritual and subvert it.[3]

Descended from a Serer family through his mother from the line of Matar Sène, Ousmane Sembène was particularly drawn to Serer religious festivals. He especially was intrigued by the Tuur festival.[4]

Early life

editThe son of a fisherman and his wife, Ousmane Sembène was born in Ziguinchor in Casamance to a Lebou family. From childhood he was exposed to the Serer religion through his mother's people, especially the Tuur festival, in which he was made "cult servant". Although the Tuur demands offerings of curdled milk to the ancestral spirits (Pangool), Sembène did not take his responsibility as cult servant seriously and was known for drinking the offerings made to the ancestors.[4] Some of his adult work draws on Serer themes. His maternal grandmother reared him and greatly influenced him. Women play a major role in his works.[4]

Sembène's knowledge of French and basic Arabic besides Wolof, his mother tongue, followed his attendance at a madrasa, as was common for many Muslim boys, and a French school until 1936, when he clashed with the principal. Sembène worked with his father—he was prone to seasickness—until 1938. At the age of fifteen, he moved to Dakar, where he worked a variety of manual labour jobs.[5]

In 1944, during World War II and after the Fall of France, Sembène was drafted into the Senegalese Tirailleurs (a corps of the French Army).[6] His later World War II service was with the Free French Forces. After the war, he returned to his home country. In 1947 he participated in a long railroad strike, on which he later based his seminal novel God's Bits of Wood (1960).

Late in 1947, Sembène stowed away to reach France, where he worked at a Citroën factory in Paris. He went south to work on the docks at Marseille, where he became active in the French trade union movement. He joined the communist-led CGT and the Communist party, helping lead a strike to hinder the shipment of weapons for the French colonial war in Vietnam. During this time, he discovered the Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay and the Haitian Marxist writer Jacques Roumain.

Early literary career

editSembène taught himself to read and write in French. He drew on many of his life experiences in his debut novel, Le Docker Noir, written in French (1956, later published in English as The Black Docker).[2] This was the story of Diaw, an African stevedore who faces racism and mistreatment on the docks at Marseille. Diaw writes a novel, which is later stolen by a white woman and published under her name. When he confronts her, he accidentally kills her. He is tried and executed in scenes highly reminiscent of Albert Camus's The Stranger (1942, also translated as The Outsider). [citation needed]

Though Sembène focuses particularly on the mistreatment of African immigrants, he also details the oppression of Arab and Spanish workers. He demonstrates that the issues concern xenophobia as much as they do race. This is written in a social realist mode, as was much of his subsequent fiction. His debut marked the beginning of Sembène's literary reputation. The success of this novel provided enough financial return so that he could continue writing.[citation needed]

Sembène's second novel, O Pays, mon beau peuple! (Oh country, my beautiful people!, 1957), tells the story of Oumarf. He is an ambitious black Senegalese farmer who returns to his native Casamance with a new white wife and ideas for modernizing the area's agricultural practices. Oumar struggles against both the French colonial government and the village social order, and he is eventually murdered. O Pays, mon beau peuple! was an international success, and Sembène received invitations from around the world, particularly from Communist countries such as China, Cuba, and the Soviet Union.[citation needed]

Sembène's third and most famous novel is Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu (God's Bits of Wood, 1960);[2] most critics consider it his masterpiece, rivaled only by Xala. The novel is a fictional treatment of the railroad strike on the Dakar-Niger line, which lasted from 1947 to 1948. Though the charismatic and brilliant union spokesman, Ibrahima Bakayoko, is the most central figure, the novel has no true hero except the community itself. The people band together in the face of hardship and oppression to assert their rights. Accordingly, the novel features nearly fifty characters in both Senegal and neighboring Mali, showing the strike from all possible angles. In this, the novel is often compared to Émile Zola's Germinal.[citation needed]

Sembène followed Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu with the short fiction collection Voltaïque (Tribal Scars, 1962). The collection contains short stories, tales, and fables, including "La Noire de..." which he would later adapt as his first film. In 1964, he released l'Harmattan (The Harmattan), an epic novel about a referendum for independence that takes place in an African capital.

From 1962 to 1963, Sembène studied filmmaking for a year at Gorky Film Studio, Moscow, under Soviet director Mark Donskoy. Also studying there was Sarah Maldoror, a French-Guadeloupean artist who became the first woman to make a feature film in Africa.[7]

Later literary career

editWith the 1965 publication of the novellas Le mandat, précédé de Vehi-Ciosane (The Money Order and White Genesis), Sembène's emphasis began to shift. Just as he had once attacked the racial and economic oppression conducted by the French colonial government, with these works, he turned his attention to the corrupt African elites who followed during independence.

He was among the contributors to the magazine Lotus, which was launched in Cairo in 1968 and financed by Egypt and the Soviet Union.[8]

Sembène continued this theme with the novel Xala (1973), the story of El Hadji Abdou Kader Beye, a rich businessman. On the very night of his wedding to his beautiful, young third wife, El Hadji suffers impotence ("xala" in Wolof), and believes it to be caused by a curse. El Hadji grows obsessed with removing the curse through visits to marabouts. Only after losing most of his money and reputation does he discover he was cursed by the beggar who lives outside his offices, whom he had wronged in the course of acquiring his fortune.

Le Dernier de l’empire (The Last of the Empire, 1981), Sembène's last novel, depicts corruption and an eventual military coup in a newly independent African nation. His paired 1987 novellas Niiwam et Taaw (Niiwam and Taaw) continue to explore social and moral collapse in urban Senegal.

On the strength of Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu and Xala, Sembène is considered one of the leading figures in African postcolonial literature. Samba Gadjigo notes that his influence reached audiences beyond Africa, "Of Sembène's ten published literary works, seven have been translated into English".[9] By contrast, the Nigerian pioneer writers Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka wrote their works in English, which eased their recognition beyond Nigeria.

Film

editAs an author concerned with social change, Sembène wished to touch a wide audience. He realized that his written works would reach only the cultural elites, but that films were "the people's night school"[2] and could reach a much broader African audience.

In 1963, Sembène produced his first film, a short called Barom Sarret (The Wagoner). In 1964 he made another short, entitled Niaye. In 1966 he produced his first feature film, La Noire de..., based on one of his own short stories; it was the first feature film ever released by a sub-Saharan African director. Though only 60 minutes long, the French-language film won the Prix Jean Vigo,[2] bringing immediate international attention to both African film generally and Sembène specifically. Sembène followed this success with the 1968 Mandabi, achieving his dream of producing a film in his native Wolof language.[2]

His later Wolof-language films include Xala (1975, based on his own novel), Ceddo (1977), Camp de Thiaroye (1987), and Guelwaar (1992). The Senegalese release of Ceddo was strongly censored, ostensibly for a problem with Sembène's paperwork, though some critics suggest that this censorship had more to do with the government's interpretation of what could be considered anti-Muslim content in the film.[10][11][12]

Sembène resisted this action by distributing fliers at theaters describing the censored scenes, and he released the film uncut for the international market.

In 1971, Sembène also made a film in French and Diola, entitled Emitaï. It was entered into the 7th Moscow International Film Festival, where it won a Silver Prize. It was banned by governments throughout French West Africa.[10][13][14] His 1975 film Xala was entered into the 9th Moscow International Film Festival.[15]

In 1977 his film Ceddo was entered into the 10th Moscow International Film Festival.[16] In the same year Sembène was invitted to be a member of the jury at the 27th Berlin International Film Festival.[17] At the 11th Moscow International Film Festival in 1979, he was awarded with the Honorable Prize for the contribution to cinema.[18]

Recurrent themes of Sembène's films are the history of colonialism, the failings of religion, the critique of the new African bourgeoisie, and the strength of African women.

His final film, the 2004 feature Moolaadé, won awards at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival[19] and the FESPACO Film Festival in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. The film, set in a small African village in Burkina Faso, explored the controversial subject of female genital mutilation.

Sembène often makes a cameo appearance in his films. For example, in Mandabi he plays the letter writer at the post office.[20]

Death

editOusmane Sembène died on 9 June 2007, at the age of 84. He had been ill since December 2006, and died at his home in Dakar, Senegal, where he was buried in a shroud adorned with Quranic verses.[21] Sembène was survived by three sons from two marriages.[22]

Seipati Bulane Hopa, Secretary General of the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI), described Sembène as "a luminary that lit the torch for ordinary people to walk the path of light...a voice that spoke without hesitation, a man with an impeccable talent who unwaveringly held on to his artistic principles and did that with great integrity and dignity."[23]

South Africa's Pallo Jordan, Minister of Arts and Culture, went further in eulogizing Sembène as "a well rounded intellectual and an exceptionally cultured humanist...an informed social critic [who] provided the world with an alternative knowledge of Africa."[23]

Works

editBooks

edit- Sembène, Ousmane (1956). Le Docker noir. Paris: Debresse. Also a new edition by publisher Présence Africaine of 2002.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1987). Black docker. African writers. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9780435908966. OCLC 16084389.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1989). Black docker. African writers. Oxford: Heinemann. ISBN 9780435908973. OCLC 476822988.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1957). O Pays, mon beau peuple!. Amiot Dumont, 1957. OCLC 1009422560.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1988). Les bouts de bois de Dieu : Banty mam yall. [Paris]: Le Livre Contemporain. OCLC 62109468. A later edition of the original of 1960.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1995). God's Bits of Wood. Translated by Price, Francis. London: Heinemann. OCLC 562242510.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1962). Voltaïque (fr). Paris: Présence Africaine. OCLC 312515053. Short stories.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1974). Tribal scars and other stories. Washington: INSCAPE. ISBN 9780879530150. OCLC 763705.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1964). L'Harmattan (novel). Paris: Présence Africaine. OCLC 460661419. Reprint 1973.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1965). Vehi-Ciosane ou Blanche-Genèse, suivi du Mandat. Paris: Présence Africaine (Ligugé, impr. Aubin). OCLC 460661424.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1987). The Money-Order with White Genesis. Translated by Wake, Clive. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9780435900922. OCLC 572500.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1973). Xala. Paris: Présence africaine.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1981). Le dernier de l'Empire. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782858021697. OCLC 405576233.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1983). The last of the Empire : a Senegalese novel. Translated by Adams, Adrian. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9780435902506. OCLC 10030343. "A key to Senegalese politics" – Werner Glinga.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1987). Niiwam : nouvelles. Paris: Présence africaine. ISBN 9782708704862. OCLC 631337297.

- Sembène, Ousmane (1991). Niiwam and Taaw [two novellas]. [Cape Town]: D. Philip. ISBN 9780864861221. OCLC 24360778. Also Oxford and Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann, 1992.

Selected filmography

editSembène's films include:[24][25][26][27]

| Year | Film | Genre | Role | Duration (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Borom Sarret | Drama short Portrait of a poor Senegalese man. First film made by a black African.[26] |

Director and writer | 20 m |

| 1964 | Niaye | Drama short The scandal of a pregnant young girl |

Director and writer | 35 m |

| 1966 | Black Girl (original title: La noire de...) | Drama feature A Senegalese girl becomes a servant in France |

Director and writer | 65 m |

| 1968 | Mandabi | Drama feature A Senegalese man has to cope with a money order from Paris |

Director and writer | 92 m |

| 1970 | Tauw | Drama short A young man makes a home for his pregnant girlfriend |

Director and writer | 24 m |

| 1971 | Emitaï | Drama feature Jola people protest World War II French conscription |

Director and writer | 103 m |

| 1975 | Xala | Comedy feature A corrupt politician is cursed with impotence |

Director and writer | 123 m |

| 1977 | Ceddo | Drama feature In protest outsiders (Ceddo, non-muslims) kidnap a black princess |

Director and co-writer with Carrie Sembene | 120 m |

| 1988 | Camp de Thiaroye | Historical drama feature In the 1944 Thiaroye massacre French troops kill rebelling returned black soldiers |

Co-director and co-writer with Thierno Faty Sow | 147 m |

| 1992 | Guelwaar | Drama feature Religious and political satire on an erroneous burial |

Director and writer | 115 m |

| 2000 | Faat Kiné | Drama feature An unwed mother succeeds professionally |

Director and writer | 120 m |

| 2004 | Moolaadé | Drama feature Women protest female genital mutilation |

Director and writer | 124 m |

Further reading

edit- Adeniyi, Idowu Emmanuel (2019). "Male Other, Female Self and Post-feminist Consciousness in Sembène Ousmane's God's Bits of Wood and Flora Nwapa's Efuru". Ibadan Journal of English Studies. 7: 57–72.

- Busch, Annett; Annas, Max (2008). Ousmane Sembène interviews. [Jackson]: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781934110850. OCLC 778204000.

- "Ousmane Sembène: Interviews. Edited by Annett Busch and Max Annas". upress.state.ms.us. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

Culture is political, but it's another type of politics. In art, you are political, but you say, 'We are' and not 'I am.'

- "Ousmane Sembène: Interviews. Edited by Annett Busch and Max Annas". upress.state.ms.us. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Gadjigo, Samba; Faulkingham, Ralph H.; Cassirer, Thomas; Sander, Reinhard, eds. (1993). Ousmane Sembène : dialogues with critics and writers. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 9780870238895. OCLC 28339413.

- Gadjigo, Samba (2010). Ousmane Sembène : the making of a militant artist. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253354136. OCLC 313659212.

- Mumin, Nijla (4 October 2013). "Caméras d'Afrique: Elvis Mitchell On West African Cinema and The Need for Diverse Film Criticism (Interview)". IndieWire. Penske Business Media, LLC. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Murphy, David (2001). Imagining Alternatives in Film and Fiction – Sembene'. Oxford: Africa World Press Inc. ISBN 9780852555552. OCLC 254943835.

- Niang, Sada; Gadjigo (Fall 1995). "Interview with Ousmane Sembene". Research in African Literatures. 26 (3): 174–178.

- Niang, Sada (1996). Littérature et cinéma en afrique francophone: Ousmane Sembène et Assia Djebar. Paris: L’Harmattan. ISBN 9782738448750. OCLC 917569861.

- Pfaff, Françoise (1984). The Cinema of Ousmane Sembene: A Pioneer of African Film. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313244001. OCLC 10605185.

- Rubaba, Protas Pius (2009). "The influence of feminist communication in creating social transformation: an analysis of the films Moolaade (Ousmane Sembene) and Water (Deepa Mehta)" (PDF). vital.seals.ac.za. South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS). p. 132. Master thesis in Applied Media Studies, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University.

- Vieyra, Paulin Soumanou (1972). Ousmane Sembène cineaste: première période, 1962–1971. Paris: Présence Africaine. OCLC 896779795.

References

edit- ^ Samba Gadjigo (6 May 2010). Ousmane Sembène: The Making of a Militant Artist. Indiana University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-253-00426-0.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ousmane Sembene, 84; Senegalese hailed as 'the father of African film'". Los Angeles Times. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Jonassaint, Jean (2010). "Le cinéma de Sembène Ousmane, une (double) contre-ethnographie : (Notes pour une recherche)". Ethnologies (in French). 31 (2): 241–286. doi:10.7202/039372ar. ISSN 1481-5974. S2CID 192052034.

- ^ a b c (in English) Gadjigo, Samba, "Ousmane Sembène: The Making of a Militant Artist", Indiana University Press, (2010), p 16, ISBN 0253354137 [1] (Retrieved : 10 August 2012)

- ^ "Ousmane Sembene: The Life of a Revolutionary Artist". newsreel.org. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Busch, Annett; Annas, Max (2008). Ousmane Sembène: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781934110867.

- ^ Harding, Jeremy (23 May 2024). ""I am only interested in women who struggle"". London Review of Books: 31–34.

- ^ Firoze Manji (3 March 2014). "The Rise and Significance of Lotus". CODESRIA. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Samba Gadjigo "OUSMANE SEMBENE: THE LIFE OF A REVOLUTIONARY ARTIST" California Newsreel, San Francisco [2]

- ^ a b "Emitai Ceddo". Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ Berridan, Brenda F. (2004), Manu Dibango and Ceddo's "Transatlantic Soundscape", in Focus on African Films. Indiana University Press, p. 151.

- ^ Busch, Annett, and Max Annas (eds), (2008). Ousmane Sembène: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, p. 135.

- ^ "Ceddo Emitai Ousmane Sembene". 2 February 1998. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "7th Moscow International Film Festival (1971)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ "9th Moscow International Film Festival (1975)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "10th Moscow International Film Festival (1977)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Berlinale 1977: Juries". berlinale.de. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ^ "11th Moscow International Film Festival (1979)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Moolaadé". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ Francoise, Pfaff (1993). "The Uniqueness of Ousmane Sembene's Cinema". Contributions in Black Studies. 11 (1).

- ^ Callimachi, Rukmini "Father of African cinema buried in Senegal" 12 June 2007. [3] Archived 22 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Macnab, Geoffrey (13 June 2007). "Obituaries – 'Ousmane Sembene'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ a b Tributes to Ousmane Sembene: 1923 – 2007 Archived 24 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, screenafrica.com

- ^ "Ousmane Sembène. Réalisateur/trice, Ecrivain/ne, Acteur/trice, Producteur/trice, Scénariste, Personne concernée. Sénégal". africultures.com (in French). Africultures. Les mondes en relation. 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ "Ousmane Sembène Film director, Writer, Actor, Producer, Screenwriter, Person concerned". africine.org. Fédération africaine de la critique cinématographique (FACC). 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ a b Ousmane Sembène at IMDb

- ^ "Ousmane Sembène Director". New York: African Film Festival, Inc. (AFF). Retrieved 8 October 2023.

External links

editVideos

edit- Ceddo (1977), with English and French Subtitles (**enable Closed Caption for English subtitles**) on YouTube. Video duration 1h:51m:41s. Uploader XMusicMusicX 2013.

- FILM GUELEWAR Ousmane Sembene 1992 (en Français) on YouTube. Video duration 1h:29m:38s. Uploader Roomnart 2022.

General

edit- "Authors & Artists. Sembene, Ousmane". scholarblogs.emory.edu. Postcolonial Studies, Emory University. 19 August 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

As far as I am concerned, I no longer support notions of purity. Purity has become a thing of the past. . .

- Ousmane Sembène at IMDb

- Gadjigo, Samba. "Ousmane Sembene: the life of a revolutionary artist". newsreel.org. California Newsreel, San Francisco. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

Crossing the geographical and national borders of his native Senegal, Ousmane Sembene's literary and cinematographic output places him today as the "father" of African films and as one of the most prolific "French-speaking" African writers in this first century of "creative" writing in francophone Africa.

- "Interview with Ousmane Sembène — father of African film". socialistworker.co.uk. Socialist Worker. 11 June 2005. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Scott, A.O. (11 June 2007). "An Appraisal: A Filmmaker Who Found Africa's Voice". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Scott, A.O. (12 June 2007). "Ousmane Sembène, 84, Dies; Led Cinema's Advance in Africa". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- "Ousmane Sembène. Réalisateur/trice, Ecrivain/ne, Acteur/trice, Producteur/trice, Scénariste, Personne concernée. Sénégal". africultures.com (in French). Africultures. Les mondes en relation. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Busch, Annett; Annas, Max. "Ousmane Sembene Interviews". missingimage.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- "Ousmane Sembene". wnyc.org. New York Public Radio, WNYC. 12 October 2004. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene on his distinguished and prolific career, as well as his latest film: Moolaadé.

Duration 31 min 20 sec. Audio file of the interview on the Leonard Lopate show. - Amekudji, Anoumou (23 October 2009). "Selected lines of the book "Ousmane Sembène Interviews"". blog.cineafrique.org/. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

I interviewed Sembène Ousmane on July 25, 2006. We were supposed to meet again to continue the discussion and talk about other elements of his Cinema but he passed away at the beginning of June 2007.

- "Ousmane Sembène. The Making of a Militant Artist. Samba Gadjigo. Translated by Moustapha Diop. Foreword by Danny Glover". iupress.indiana.edu. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. 2010. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- "Sembène: The Making of African Cinema (1994)". maumaus.org. Lisbon, Portugal: Associação Maumaus - Centro de Contaminação Visual. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

In this rich documentary, legendary Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène reminisces about his career and discusses the craft of his films and novels.

Review of the film by Manthia Diawara and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o.

In French

edit- Amekudji, Anoumou. "Rencontre avec Sembène Ousmane, écrivain-cinéaste sénégalais". blog.cineafrique.org (in French). Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

Article paru dans l'hebdomadaire sénégalais, Weekend, l'hebdo du Quotidien, Semaine du 2 au 8 aout 2007

. One of the last interviews of Sembene Ousmane. - Barlet, Olivier (27 May 2005). "La leçon de cinéma d'Ousmane Sembène au festival de Cannes 2005" (in French). Archived from the original on 23 November 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Barlet, Olivier (11 June 2007). "Sembène, le mécréant". africultures.com (in French). africultures. Les mondes en relation. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Barlet, Olivier (15 August 2007). "Entretien avec Ousmane Sembène". africultures.com (in French). africultures. Les mondes en relation. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "LE PÈRE DU CINÉMA AFRICAIN. Ousmane Sembène, le Dakarois en perpétuelle révolte". courrierinternational.com (in French). Courier International. 15 December 2004. Retrieved 7 October 2023. Ultimate source: International Herald Tribune.

- "Cinéma > Ousmane SEMBENE". senegalaisement.com (in French). Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2023.