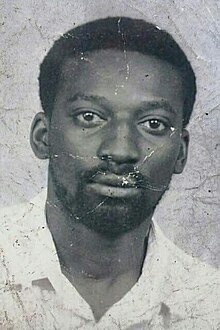

Omar Blondin Diop (1946–1973) was a West-African anti-imperialist philosopher, artist, and revolutionary from Senegal and Mali. A figure of the May 68 uprising in France and underground opposition to Léopold Sédar Senghor in Senegal in the early 1970s, he was imprisoned for planning the freeing of detained comrades who had attempted an attack on French president Georges Pompidou while on a visit to Dakar. His death in custody in May 1973 caused national and international outrage, and played a role in the establishment of a multi-party system in Senegal as of the mid-1970s.

Omar Blondin Diop | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 September 1946 |

| Died | 11 May 1973 |

| Cause of death | Homicide |

| Body discovered | Gorée Civil Prison, Cell no. 3 |

| Burial place | Soumbedioune Cimetary |

| Nationality | Senegalese |

| Education | École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud |

| Alma mater | Lycée Louis-le-Grand |

| Occupation | Philosopher |

| Political party | UEC (1964–1966) UJC(ml) (1966–1968) MJML (1970) |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Biography

editOmar Blondin Diop was born on September 18, 1946, in Niamey, Niger. His mother, Adama Ndiaye, was a midwife, and his father, Ibrahima Blondin Diop, was a general practitioner, who had been transferred to the French colony of Niger for “anti-French sentiment”. His family later returned to Senegal, where he spent most of his childhood. After a first stay in 1957, Diop definitively settled in France in 1960 after his father enrolled in doctoral medical school.

In Paris, he studied philosophy and attended the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand high school as well as the École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud teachers’ college,[1] where he actively partook in debates organized by far-left groups like the Union of Communist Students and the Union of Communist Youth Marxist-Leninist. Shortly after hearing about the Senegalese activist, Swiss film director Jean-Luc Godard selected him to play the role of a radical student-professor, “comrade X”, in the 1967 movie La Chinoise. A regular of Nanterre University, Diop joined the March 22 Movement, which played an important role leading up to the May 68 protests.

For his political activities, Diop was expelled to Senegal in 1969. In Dakar, he developed artistic projects alongside the future founders of the Laboratoire Agit’Art, and maintained his activism, agitating against Léopold Sédar Senghor’s French-backed government[2] with other young radicals in the Movement of Young Marxist–Leninists (MJML).[3]

Diop left for France again in 1970, after the reversal of his entrance ban. But in February 1971, his comrades, including two younger brothers, were caught for an attempted attack on French president Georges Pompidou’s motorcade during his visit to Dakar. After learning about the arrests, Diop crossed Europe with friends and reached Syria, projecting to kidnap the French ambassador to Senegal in exchange for the prisoners. In May 1971, the group left for North Africa, hoping to garner support from the Black Panther Party which had opened an international office in Algiers.[4] But an open conflict between leaders Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton jeopardized the link-up with the National Liberation Front set out to offer logistic and diplomatic support. The group moved closer to Senegal in June 1971, reorganizing from Bamako where part of Diop’s family lived. Monitored by the Malian military junta led by Moussa Traoré, they were arrested in Novembre 1971, extradited to Senegal in February 1972 and sentenced to three years of prison for “being a threat to national security”.[5]

On May 11, 1973, Senegalese authorities announced his death in custody. The state’s version of a “suicide by hanging” provoked the anger of thousands of youths who stormed the streets. His younger brother Mohamed, an ear-witness from the neighbouring cell, heard him agonise from blows he had received to the neck. This was confirmed by the autopsy conducted by his father, medical doctor Ibrahima Blondin Diop.[6] Faced with the evidence, Dakar’s High Court senior investigating judge, Moustapha Touré, proceeded to convict two prison guards. Judge Touré stated: “The circumstances showed credible and concordant evidence that indicated that the suicide, officially mentioned to justify the death of Omar Blondin Diop, was, in fact, a cover-up”. Soon after the indictment, the judge was removed from the case and replaced by another, who ended the legal proceedings a year and a half later, claiming the case was not within his jurisdiction.[7]

Ever since, his family has tirelessly demanded justice be done. Today, his image prominently features in anti-government and anti-imperialist gatherings. On March 2, 2021, just hours before Senegalese opposition leader Ousmane Sonko’s arrest, the Front for an Anti-Imperialist Popular and Pan-African Revolution (FRAPP), a major youth-led protest organisation, held a press conference to call for mobilisation against the “project to liquidate opposition activists” in Senegal. Diop’s portrait stood prominently behind the speakers at the presser.[8]

References

edit- ^ Bobin, Florian (February 25, 2021). "Manufacturing Madness: Omar Blondin Diop against French educational elitism". Roape.net.

- ^ Hendrickson, Burleigh J. (2022). Decolonizing 1968 : transnational student activism in Tunis, Paris, and Dakar. Ithaca, New York. ISBN 978-1-5017-6624-4. OCLC 1312652411.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bianchini, Pascal (2019). "The 1968 years: revolutionary politics in Senegal". Review of African Political Economy. 46 (160): 184–203. doi:10.1080/03056244.2019.1631150. hdl:10.1080/03056244.2019.1631150. S2CID 198694215. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Mokhtefi, Elaine (2018). Algiers, Third World capital : freedom fighters, revolutionaries, Black Panthers. Brooklyn, NY. ISBN 978-1-78873-000-6. OCLC 1005113844.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bobin, Florian (March 18, 2020). "Omar Blondin Diop: Seeking Revolution in Senegal". Review of African Political Economy.

- ^ Djigo, Djeydi (2021), Omar Blondin Diop, un révolté, 78’. Invictus/Élever la voix.

- ^ Coulibaly, Abdou Latif (December 21, 2009). "Interview de Moustapha Touré, président démissionnaire de la CENA".

- ^ Bobin, Florian (May 11, 2021). "Senegal's revolutionary icon Omar Blondin Diop deserves justice". Aljazeera.