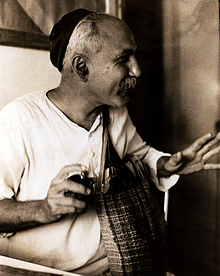

Nariman (Nari) Dossabhai Gandhi (1934–1993) was an Indian architect known for his highly innovative works in organic architecture.[1][2] He practiced as an architect in India from 1964 to 1993 having worked on approximately 27 projects.[3] He primarily focused on designing residences with a secondary focus on designing furniture, objects, and upholstery textiles.[4]

Nariman (Nari) Gandhi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 January 1934 Surat, India |

| Died | 18 August 1993 (aged 59) Khopoli near Mumbai, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Daya residence (Mumbai), Patel residence (Surat), Gateway to mosque (Kolgaon), Jain house (Lonavala) |

Early life and education

editNari Gandhi was born on 2 January 1934 in Surat to a Zoroastrian Parsi family based in Mumbai.[5][6] He was one of the six children and had three brothers and two sisters.[5]

He completed his primary and secondary education at St. Xavier's High School located in Fort, Mumbai.[7] He then attended the Sir J. J. School of Art in Mumbai and pursued the diploma program in architecture until 1956.[8] During his time at the Sir J. J. School of Art, he was acquainted with Rustom Patell, a former Taliesin (1949-1952), who, in turn, introduced him to a colleague from Taliesin, Mansinh Rana (1947-1951).[9] Upon recommendation from Rana, he left the Sir J. J. School of Art without completing his formal education to join Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin.[9]

Taliesin

editFollowing his departure from the Sir J. J. School of Art, Nari Gandhi attended Taliesin from October 1956 through December 1961.[10] The time spent training and collaborating with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin heavily influenced Gandhi's views on organic architecture.[11] The environment at Taliesin was conducive for artists to explore and engage in various forms of artistic express; it was here that, along with architecture, he became interested in stonework and pottery.[12]

His interest in stonework helped him leave an enduring mark at Taliesin. He once ignored the mandatory Sunday breakfast with Frank Lloyd Wright and Olgivanna Lloyd Wright to instead drag a large stone that he had discovered in the mountains down to the Taliesin campus. This stone—referred to as Eagle Stone or more rarely as Nari's Rock—was erected at the entrance of the Taliesin campus.[13]

He befriended architect Bruce Goff during his time at Taliesin.[14] After leaving Taliesin, he briefly worked with architect Warren Webber before studying pottery, weaving, ceramics, photography, and woodcarving at Kent State University.[15]

Career

editFollowing his studies at Kent State University, Nari Gandhi returned to India to practice as an independent architect.[16] He owned an office space on Nepeansea Road near Malabar Hill in South Mumbai but it was rarely occupied and used.[17] He was not a registered architect with the Indian Institute of Architects so the legal permits for his projects were obtained by an architect-friend, Dady Banaji, and other associates.[18]

He practiced as an architect in India from 1964 to 1993 having worked on approximately 27 projects.[3] He primarily focused on designing residences (apartments, penthouses, farm houses, beach houses) with a secondary focus on designing furniture, objects, and upholstery textiles.[4]

His work-team included Pravin Bhayani—acknowledged by Gandhi as his 'troubleshooter'—and Arvind Soni—who was responsible for the on-site labour force.[19]

Architectural style

editNari Gandhi was known for his highly innovative works in organic architecture that blended elements unique to India with the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright.[11] He developed an integrated architectural style that considered the local climate, tropical lifestyle, and artisanship in collaboration with the craftsmen and masons on site.[11] Labor-intensive methods were intrinsic to his work, which showed a refined sense of materials with an extraordinary use of clay, stone, brick, wood, glass, and leather.[20]

Recurring themes in his work include extended roof slopes that touch the ground, arched structural design, preservation of and building around on-site trees, and obscuring the interior-exterior distinction.[19] The idea of constant growth and change, as evident through rebuilding, rearranging, and extending, was also present in his work.[21]

Personal life

editNari Gandhi was a practicing Zoroastrian Parsi who dressed plainly in white, khadi fabric kurta pyjamas, a Parsi top, and Kolhapuri chappals.[22] He was a bachelor and a teetotaler.[22] He was influenced by the ideas of the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti.[23]

He died in a car accident on 18 August 1993 while on a visit to a client's site.[5]

Selected works

edit- Jal Gobhai's mountain lodge (Lonavala)[24]

- Asha Parekh's Akruti residence (Juhu, Mumbai)[25][26]

- Valia resident (Vile-Parle, Mumbai)[27]

- Interior design for Vasant Seth's penthouse (Mumbai)[28]

- Sam Dastoor's weekend house (Madh Island, Mumbai)[29]

- Vasant Seth's beach house[30]

- Landscape and furniture design for Moondust (Versova)[21]

- Sadruddin Daya's Revdanda residence (Revdanda, Maharashtra)[31]

- Sadruddin Daya's Mark Haven apartment (Coloba, Mumbai)[32]

- Suryakant Patel's residence (Surat, Gujarat)[32]

- Interior design for Mr. Malik Tejani's apartment (Kanchanjunga, Mumbai)[33]

- Rustom Mehta's residence (Korlai, Maharashtra)[34]

- Jain (co-owners of the Times of India group) bungalow (Lonavala)[35][36]

- Kishore Bajaj's farmhouse (Karjat)[37]

- Nasir Jamal's penthouse (Colaba, Mumbai)[38]

- Abu Asim Azmi's penthouse (Colaba, Mumbai)[38]

- Sadruddin Daya's Madh Island house (Madh Island, Mumbai) (unfinished)[39]

- Malik Tejani's Tungarli bungalow (Lonavala)[40]

- Madhusthali Vidyapeeth girls school (Madhpur, Jharkhand) (unfinished)[41]

Notes

edit- ^ Jon T. Lang (2002). A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India. Orient Blackswan. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-81-7824-017-6.

- ^ Donald Leslie Johnson; Donald Langmead (13 May 2013). Makers of 20th-Century Modern Architecture: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook. Routledge. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-1-136-64063-6.

- ^ a b Jalia 2008, p. 36

- ^ a b Jalia 2008, p. 36, p. 106

- ^ a b c "Ar. Nari Gandhi (1934 - 1993): A Maverick, A Legend". www.tfod.in. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 84

- ^ "Alumni | St. Xavier's High School". stxaviersfort.org. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 11, p. 13

- ^ a b Hawker 2007, p. 2-4, cited in Jalia 2008, p. 14

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 15

- ^ a b c Jalia 2008, p. 9

- ^ Hawker 2007, p. 2 cited in Jalia 2008, p. 17

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 17

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 19

- ^ Hawker 2007, p. 9 cited in Jalia 2008, p. 26

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 26

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 35

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 33

- ^ a b Jalia 2008, p. 44

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 34

- ^ a b Jalia 2008, p. 48

- ^ a b "This Nari Gandhi-designed red-brick house stands above its peers in Alibag". Architectural Digest India. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Nanda, Puja (June 1999). The Culture of Building to Craft — A Regional Contemporary Aesthetic: Material Resources, Technological Innovations and the Form Making Process (MSc thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ Hawker 2007, p. 10-11 cited in Jalia 2008, p. 37-39

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 40

- ^ Ganesan-Ram, Sharmila (26 July 2009). "Remembering the Howard Roark of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Hawker 2007, p. 14 cited in Jalia 2008, p. 41

- ^ Hawker 2007, p. 15 cited in Jalia 2008, p. 43

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 43-46

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 43

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 54

- ^ a b Jalia 2008, p. 57

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 58

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 61

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 61

- ^ Hawker 2007, p. 36 cited in Jalia 2008, p. 65

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 68

- ^ a b Jalia 2008, p. 72

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 76

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 79

- ^ Jalia 2008, p. 81

References

edit- Jalia, Aftab Amirali. (2008). Refiguring the Sketch: The Nari Gandhi Cartographic (MSc). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Hawker, Michael C. (2007). "Celebrating the life and work of Nari Gandhi". Friends of Kebyar. Volume 23.1, Issue No. 72.

Further reading

edit- H MasudTaj (2009). Nari Gandhi. Foundation Forarchitecture. ISBN 978-81-908832-0-7.