You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (February 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (October 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Marco Polo Bridge incident, also known as the Lugou Bridge incident[a] or the July 7 incident,[b] was a battle during July 1937 in the district of Beijing between the 29th Army of the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China and the Imperial Japanese Army.

| Marco Polo Bridge incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Sino-Japanese War | |||||||

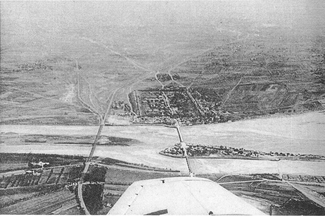

Aerial photo of the Marco Polo Bridge (right). Wanping Fortress is on the opposite side of the river. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 29th Army | Japanese China Garrison Army | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

100 troops at the bridge[2] 900 in reinforcement | 5,600[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 96 killed[2] | 660 killed | ||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 盧溝橋事變 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 卢沟桥事变 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Lugou Bridge incident | ||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lúgōuqiáo Shìbiàn | ||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 七七事變 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 七七事变 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | July 7 incident | ||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Qīqī Shìbiàn | ||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 盧溝橋事件 | ||||||

| Revised Hepburn | Rokōkyō Jiken | ||||||

Location within Beijing | |||||||

Since the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, there had been many small incidents along the rail line connecting Beijing with the port of Tianjin, but all had subsided. In this incident, a Japanese soldier was temporarily absent from his unit opposite Wanping, and his commander demanded the right to search the town for him. When this request was refused, units on both sides were alerted and the Chinese Army fired on the Japanese Army. However, the missing Japanese soldier had already returned to his lines. The Marco Polo Bridge incident is generally regarded as the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War.[4]

Introduction

editIn English, the battle is usually known as the "Marco Polo Bridge incident".[5] The Marco Polo Bridge is an eleven-arch granite bridge, an architecturally significant structure first erected under the Jin dynasty and later restored during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty in 1698. It gained its Western name from its appearance in Il Milione, Marco Polo's record of his travels.[6]

It is also known as the "Lukouchiao",[7] "Lugouqiao",[8] or 'Lugou Bridge incident' from the local name of the bridge, derived from a former name of the Yongding River.[9] This is the common name for the event in Japanese (蘆溝橋事件, Rokōkyō Jiken) and is an alternate name for it in Chinese and Korean (노구교사건, Nogugyo Sageon). The same name is also expressed or translated as the "Battle of Lugou Bridge",[10] "Lugouqiao",[11] or "Lukouchiao".[12]

Background

editTensions between the Empire of Japan and the Republic of China had been heightened since the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and their subsequent creation of a client state, Manchukuo, with Puyi, the deposed Qing dynasty emperor, as its chief of state. After the invasion, Japanese forces extended their control further into northern China, seeking to obtain raw materials and industrial capacity. A commission of inquiry from the League of Nations published the Lytton Report which was critical of the Japanese, resulting in Japan quitting the League.[13]

The Kuomintang (KMT) government of China refused to recognize Manchukuo but did agree to the Tanggu Truce with Japan in 1933. Subsequently, there were various "incidents", or armed clashes of a limited nature, followed by a return to uneasy peace. The significance of the Marco Polo Bridge incident is that, following it, tensions did not subside again; instead, there was an escalation, with larger forces committed by both sides and fighting spreading to other parts of China. With hindsight, this small incident can, therefore, be regarded as the start of a major conflict.[14]

By the terms of the Boxer Protocol of 7 September 1901, China had granted nations with legations in Beijing the right to station guards at twelve specific points along railways connecting Beijing with Tianjin. This was to ensure open communications between the capital and the port. By a supplementary agreement on 15 July 1902, these forces were allowed to conduct maneuvers without informing the authorities of other nations in China.[15]

By July 1937, Japan had expanded its forces in China to an estimated 7,000 to 15,000 men, mostly along the railways. This number of men, and the amount of concomitant matériel, was several times the size of the detachments deployed by the European powers, and greatly in excess of the limits set by the Boxer Protocol.[15] By this time, the Imperial Japanese Army had already surrounded Beijing and Tianjin.

Incident

editOn the night of 7 July, the Japanese units stationed at Fengtai crossed the border to conduct military exercises. Japanese and Chinese forces outside the town of Wanping—a walled town 16.4 km (10.2 mi) southwest of Beijing—exchanged fire at approximately 23:00. The exact cause of this incident remains unknown. When a Japanese soldier, Private Shimura Kikujiro, failed to return to his post, Chinese regimental commander Ji Xingwen (219th Regiment, 37th Division, 29th Army) received a message from the Japanese demanding permission to enter Wanping to search for the missing soldier; the Chinese refused. Private Shimura later returned to his unit; he claimed to have sought immediate relief in the darkness from a stomach ache and become lost[16][citation needed]); according to Peter Harmsen, he had visited a brothel.[17] By that time both sides were mobilizing, with the Japanese deploying reinforcements to surround Wanping.

Later that night, a unit of Japanese infantry attempted to breach Wanping's walled defenses but were repulsed. An ultimatum by the Japanese was issued two hours later. As a precautionary measure, Qin Dechun, the acting commander of the Chinese 29th Route Army, contacted the commander of the Chinese 37th Division, General Feng Zhi'an, ordering him to place his troops on heightened alert. [citation needed]

At 02:00 on 8 July, Qin Dechun, executive officer and acting commander of the Chinese 29th Route Army, sent Wang Lengzhai, mayor of Wanping, alone to the Japanese camp to conduct negotiations. However, this proved to be fruitless, and the Japanese insisted that they be admitted into the town to investigate the cause of the incident.

At around 04:00, reinforcements of both sides began to arrive. The Chinese also rushed an extra division of troops to the area. At 04:45 Wang Lengzhai had returned to Wanping, and on his way back he witnessed Japanese troops massing around the town. Within five minutes of Wang's return, a shot was heard, and both sides began firing[citation needed], thus marking the commencement of the Battle of Beiping-Tianjin, and, by extension, the full scale commencement of the Second Sino-Japanese War at 04:50 on 8 July 1937.

Colonel Ji Xingwen led the Chinese defenses with about 100 men, with orders to hold the bridge at all costs. The Chinese were able to hold the bridge with the help of reinforcements, but suffered tremendous losses.[citation needed] At this point, the Japanese military and members of the Japanese Foreign Service began negotiations in Beijing with the Chinese Nationalist government.

A verbal agreement with Chinese General Qin was reached, whereby:[citation needed]

- An apology would be given by the Chinese to the Japanese.

- Punishment would be dealt to those responsible.

- Control of Wanping would be turned over to the Hebei Chinese civilian constabulary and not to the Chinese 219th Regiment.

- The Chinese would attempt to better control "communists" in the area.

This was agreed upon, though Japanese Garrison Infantry Brigade commander General Masakazu Kawabe initially rejected the truce and, against his superiors' orders, continued to shell Wanping for the next three hours, until prevailed upon to cease and to move his forces to the northeast.[citation needed]

Aftermath

editAlthough a ceasefire had been declared, further efforts to de-escalate the conflict failed, largely due to actions by the Chinese Communists and the Japanese China Garrison Army commanders.[citation needed] Due to constant Chinese attacks, Japanese Garrison Infantry Brigade commander General Masakazu Kawabe ordered Wanping to be shelled on 9 July. The following day, Japanese armored units joined the attack. The Chinese 219th regiment staged an effective resistance, and full scale fighting commenced at Langfang on 25 July.[citation needed] After launching a bitter and bloody attack on the Japanese lines on the 27 July, General Song Zheyuan was defeated and forced to retreat behind the Yongding River by the next day.

Battle of Beiping–Tianjin

editOn 11 July, in accordance with the Goso conference, the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff authorized the deployment of an infantry division from the Chosen Army, two combined brigades from the Kwantung Army and an air regiment composed of 18 squadrons as reinforcements to Northern China. By 20 July, total Japanese military strength in the Beiping-Tianjin area exceeded 180,000 personnel.

The Japanese gave Song and his troops "free passage" before moving in to pacify resistance in areas surrounding Beijing and Tianjin. After 24 days of combat, the Chinese 29th Army was forced to withdraw. The Japanese captured Beiping and the Taku Forts at Tianjin on 29 and 30 July respectively, thus concluding the Battle of Beiping–Tianjin. However, the Japanese Army had been given orders not to advance further than the Yongding River. In a sudden volte-face, the Konoe government's foreign minister opened negotiations with Chiang Kai-shek's government in Nanjing and stated: "Japan wants Chinese cooperation, not Chinese land." Nevertheless, negotiations failed to move further. On 9 August 1937, a Japanese naval officer was shot in Shanghai, escalating the skirmishes and battles into full scale warfare.[18]

The 29th Army's resistance (and poor equipment) inspired the 1937 "Sword March", which with reworked lyrics became the NRA's standard marching cadence and popularized the racial epithet guizi to describe the Japanese invaders.[19]

Consequences

editThe heightened tensions of the Marco Polo Bridge incident led directly to full-scale war between the Empire of Japan and the Republic of China, with the Battle of Beiping–Tianjin at the end of July and the Battle of Shanghai in August.

In 1937, during the Battle of Beiping–Tianjin the government was notified by Muslim General Ma Bufang of the Ma clique that he was prepared to bring the fight to the Japanese in a telegram message.[20] Immediately after the Marco Polo Bridge incident, Ma Bufang arranged for a cavalry division under the Muslim General Ma Biao to be sent east to battle the Japanese. The Turkic Salar people made up the majority of the first cavalry division sent by Ma.

In 1987, the bridge was renovated and the People's Anti-Japanese War Museum was built near the bridge to commemorate the anniversary of the start of the Sino-Japanese War.[21]

Controversies

editThere is debate over whether the incident could have been planned like the earlier Mukden incident, which served as a pretext for the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.[22] According to Jim Huffman this notion has been "widely rejected" by historians, as the Japanese would likely have been more concerned over the threat posed by the Soviets. Controversial conservative Japanese historian Ikuhiko Hata has suggested that the incident could have been caused by the Chinese Communist Party, hoping it would lead to a war of attrition between the Japanese army and the Kuomintang.[citation needed] However, he himself still considers this less likely than the "accidental shot" hypothesis, that the first shot was fired by a low-ranking Chinese soldier in "an unplanned moment of fear".

Order of battle

editNational Revolutionary Army

editIn comparison to their Japanese counterparts, the 29th Route Army, and generally all of the NRA for that matter, was poorly equipped and under-trained. Most soldiers were armed only with a rifle and a dao (a single-edged Chinese sword similar to a machete). Moreover, the Chinese garrison in the Lugouqiao area was completely outnumbered and outgunned; it consisted only of about 100 soldiers.[2]

| Name | Military posts | Civilian posts |

|---|---|---|

| General Song Zheyuan | Commander of 29th Army | Chairman of Hebei Legislative Committee Head of Beijing security forces |

| General Qin Dechun | Vice-Commander of 29th Army | Mayor of Beijing |

| General Tong Linge | Vice-Commander of 29th Army | |

| General Liu Ruming | Commander of the 143rd Division | Chairman of Chahar |

| General Feng Zhi'an (馮治安) |

Commander of the 37th Division | Chairman of Hebei |

| General Zhao Dengyu (趙登禹; Wade-Giles: Chao Teng-yu) |

Commander of the 132nd Division | |

| General Zhang Zizhong (張自忠; Wade-Giles: Chang Tze-chung) |

Commander of the 38th Division | Mayor of Tianjin |

| Colonel Ji Xingwen (吉星文) |

Commander of the 219th Regiment under the 110th Brigade of the 37th Division |

Imperial Japanese Army

editThe Japanese China Garrison Army was a combined force of infantry, tanks, mechanized forces, artillery and cavalry, which had been stationed in China since the time of the Boxer Rebellion. Its headquarters and bulk for its forces were in Tianjin, with a major detachment in Beijing to protect the Japanese embassy.

| Name | Position | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Lieutenant General Kanichiro Tashiro | Commander China Garrison Army | Tientsin |

| Major General Masakazu Kawabe | Commander China Garrison Infantry Brigade | Peking |

| Colonel Renya Mutaguchi | Commander 1st Infantry Regiment | Peking |

| Major Kiyonao Ichiki | Commander, 3rd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment | W of Marco Polo Bridge, 510 men |

See also

edit- Huanggutun incident (1928)

- Jinan incident (1928)

- January 28 incident (Shanghai, 1932)

- Defense of the Great Wall (1933)

Notes

edit- ^ Traditional Chinese: 盧溝橋事變; simplified Chinese: 卢沟桥事变; pinyin: Lúgōuqiáo shìbiàn

- ^ Simplified Chinese: 七七事变; traditional Chinese: 七七事變; pinyin: Qīqī shìbiàn

References

editCitations

edit- ^ "Qin Dechun". Generals.dk. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Wang Yi (2004). Common Knowledge about Chinese History. Hong Kong China Travel Press. p. 185. ISBN 962-8746-47-2.

- ^ Japanese War History library (Senshi-sousyo) No. 86 [Sino-incident army operations 1 until 1938 Jan.] p. 138

- ^ "Articles published during wartime by former Domei News Agency released online in free-to-access archive". The Japan Times Online. 2018-11-02. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 2019-06-04. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ "Marco Polo Bridge Incident". Marco Polo Bridge Incident | Asian history | Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. 30 June 2022..

- ^ Hahn, Emily (2014). The Soong Sisters. Open Road Media. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-4976-1953-1.

- ^ Kataoka, Tetsuya (1974). Resistance and Revolution in China. University of California Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-520-02553-0..

- ^ "Lugouqiao Incident", China through a Lens.

- ^ "Beijing: Its Characteristics of Historical Development and Transformation", Symposium on Chinese Historical Geography, p. 8.

- ^ "Battle of Lugou Bridge", World War 2.

- ^ Brown, Richard (2013). A Companion to James Joyce. John Wiley & Sons. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-444-34293-2..

- ^ "The Lukouchiao (Marco Polo Bridge) Battle", Colnect.

- ^ Song, Yuwu, ed. (2009). "Marco Polo Bridge incident 1937". Encyclopedia of Chinese-American Relations. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 198-. ISBN 978-0-786-44593-6.

- ^ Usui, Katsumi (1981). "On the Duration of the Pacific War". Japan Quarterly. 28 (4): 479–488. OCLC 1754204.

- ^ a b HyperWar: International Military Tribunal for the Far East [Chapter 5]

- ^ Benjamin, Lai (2018). Chinese Soldier vs Japanese Soldier: China 1937–38. Bloomsbury. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-472-82821-7. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ Harmsen, Peter (2013). Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze. p. 23.

- ^ Hoyt, Edwin Palmer (2001). Japan's War: The Great Pacific Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-0-815-41118-5.

- ^ Lei, Bryant. "New Songs of the Battlefield": Songs and Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, p. 85. University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh), 2004.

- ^ Central Press (30 Jul 1937). "He Offers Aid to Fight Japan". Herald-Journal. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "Marco Polo Bridge to Be Tourist Attraction : Chinese Spruce Up Landmark of War With Japanese". Los Angeles Times. 25 October 1987.

- ^ Huffman, James L. (31 October 2013). Modern Japan: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-135-63490-2.

Sources

edit- Dorn, Frank (1974). The Sino-Japanese War, 1937–41: From Marco Polo Bridge to Pearl Harbor. MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-532200-1.

- Dryburgh, Marjorie (2000). North China and Japanese Expansion 1933–1937: Regional Power and the National Interest. Routledge. ISBN 0-700-71274-7.

- Lu, David J (1961). From the Marco Polo Bridge to Pearl Harbor: A Study of Japan's Entry into World War II. Public Affairs Press. ASIN B000UV6MFQ.

- Furuya, Keiji (1981). The Riddle of the Marco Polo Bridge: To Verify the First Shot. Symposium on the History of the Republic of China. ASIN B0007BJI7I.