37°00′N 35°30′E / 37.0°N 35.5°E

Armenian Principality of Cilicia (1080–1198) Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (1198–1375) Կիլիկիոյ Հայոց Թագաւորութիւն | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1198/99–1375 | |||||||||||||||||

Flag of the Rubenid dynasty (1198–1219)

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Independent principality (1080–1198) Kingdom (1198–1375) | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tarson (Tarsus, Mersin) (1080–1198) Sis (Kozan, Adana) (1198–1375) | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Armenian (native language), Latin, Old French, Italian, Greek, Syriac | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity (Armenian Apostolic, Armenian Catholic)[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||

• Prince Leo II crowned as King Leo I | January 6, 1198/99 | ||||||||||||||||

• Tributary to the Mongols | 1236 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1375 | |||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 13th century[2] | 40,000 km2 (15,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 13th century[2] | 1,000,000+ | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Turkey Syria Cyprus | ||||||||||||||||

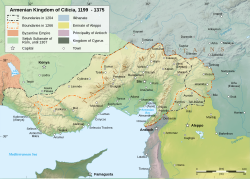

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (Middle Armenian: Կիլիկիոյ Հայոց Թագաւորութիւն, Kiligio Hayoc’ T’akavorut’iun), also known as Cilician Armenia (Armenian: Կիլիկեան Հայաստան, Kilikyan Hayastan, or Հայկական Կիլիկիա, Haykakan Kilikia), Lesser Armenia, Little Armenia or New Armenia,[3] and formerly known as the Armenian Principality of Cilicia (Armenian: Կիլիկիայի հայկական իշխանութիւն), was an Armenian state formed during the High Middle Ages by Armenian refugees fleeing the Seljuk invasion of Armenia.[4] Located outside the Armenian Highlands and distinct from the Kingdom of Armenia of antiquity, it was centered in the Cilicia region northwest of the Gulf of Alexandretta.

The kingdom had its origins in the principality founded c. 1080 by the Rubenid dynasty, an alleged offshoot of the larger Bagratuni dynasty, which at various times had held the throne of Armenia. Their capital was originally at Tarsus, and later moved to Sis.[5] Cilicia was a strong ally of the European Crusaders, and saw itself as a bastion of Christendom in the East. It also served as a focal point for Armenian cultural production, since Armenia proper was under foreign occupation at the time. Cilicia's significance in Armenian history and statehood is also attested by the transfer of the seat of the Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church, spiritual leader of the Armenian people, to the region.

In 1198, with the crowning of Leo I, King of Armenia of the Rubenid dynasty, Cilician Armenia became a kingdom.[6][7] In 1226, the crown was passed to the rival Hethumid dynasty through Leo's daughter Isabella's second husband, Hethum I. As the Mongols conquered vast regions of Central Asia and the Middle East, Hethum and succeeding Hethumid rulers sought to create an Armeno-Mongol alliance against common Muslim foes, most notably the Mamluks.[7] In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Crusader states and the Mongol Ilkhanate disintegrated, leaving the Armenian Kingdom without any regional allies. After relentless attacks by the Mamluks in Egypt in the fourteenth century, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, then under the rule of the Lusignan dynasty and mired in an internal religious conflict, finally fell in 1375.[8]

Commercial and military interactions with Europeans brought new Western influences to the Cilician Armenian society. Many aspects of Western European life were adopted by the nobility including chivalry, fashions in clothing, and the use of French titles, names, and language. Moreover, the organization of the Cilician society shifted from its traditional system to become closer to Western feudalism.[9] The European Crusaders themselves borrowed know-how, such as elements of Armenian castle-building and church architecture.[10] Cilician Armenia thrived economically, with the port of Ayas serving as a center for East–West trade.[9]

History

editEarly Armenian migrations to Cilicia

editCilicia under Tigranes the Great

editArmenian presence in Cilicia dates back to the first century BC, when under Tigranes the Great, the Kingdom of Armenia expanded and conquered a vast region in the Levant. In 83 BC, the Greek aristocracy of Seleucid Syria, weakened by a bloody civil war, offered their allegiance to the ambitious Armenian king.[11] Tigranes then conquered Phoenicia and Cilicia, effectively ending the Seleucid Empire. The southern border of his domain reached as far as Ptolemais (modern Acre). Many of the inhabitants of conquered cities were sent to the new metropolis of Tigranakert (Latin: Tigranocerta). At its height, Tigranes' Armenian Empire extended from the Pontic Alps to Mesopotamia, and from the Caspian to the Mediterranean. Tigranes invaded as far southeast as the Parthian capital of Ecbatana, located in modern-day western Iran. In 27 BC, the Roman Empire conquered Cilicia and transformed it into one of its eastern provinces.[12]

Mass Armenian migration under the Byzantine Empire

editAfter the 395 AD partition of the Roman Empire into halves, Cilicia became incorporated into the Eastern Roman Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire. In the sixth century AD, Armenian families relocated to Byzantine territories. Many served in the Byzantine army as soldiers or as generals, and rose to prominent imperial positions.[13]

Cilicia fell to Arab invasions in the seventh century and was entirely incorporated into the Rashidun Caliphate.[12] However, the Caliphate failed to gain a permanent foothold in Anatolia, as Cilicia was reconquered in the year 965 by Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas. The Caliphate's occupation of Cilicia and of other areas in Asia Minor led many Armenians to seek refuge and protection further west in the Byzantine Empire, which created demographic imbalances in the region.[12] In order to better protect their eastern territories after their reconquest, the Byzantines resorted largely to a policy of mass transfer and relocation of native populations within the Empire's borders.[12] Nicephorus thus expelled the Muslims living in Cilicia, and encouraged Christians from Syria and Armenia to settle in the region. Emperor Basil II (976–1025) tried to expand into Armenian Vaspurakan in the east and Arab-held Syria towards the south. As a result of the Byzantine military campaigns, the Armenians spread into Cappadocia, and eastward from Cilicia into the mountainous areas of northern Syria and Mesopotamia.[14]

The formal annexation of Greater Armenia to the Byzantine Empire in 1045 and its conquest by the Seljuk Turks 19 years later caused two new waves of Armenian migration to Cilicia.[14] The Armenians could not re-establish an independent state in their native highland after the fall of Bagratid Armenia, as it remained under foreign occupation. Following its conquest in 1045, and in the midst of Byzantine efforts to further repopulate the Empire's east, Armenian immigration into Cilicia intensified and turned into a major socio-political movement.[12] Armenians came to serve the Byzantines as military officers or governors, and were given control of important cities on the Byzantine Empire's eastern frontier. The Seljuks also played a significant role in the Armenian population movement into Cilicia.[12] In 1064, the Seljuk Turks led by Alp Arslan made their advance towards Anatolia by capturing Ani in Byzantine-held Armenia. Seven years later, they earned a decisive victory against Byzantium by defeating Emperor Romanus IV Diogenes' army at Manzikert, north of Lake Van. Alp Arslan's successor, Malik-Shah I, further expanded the Seljuk Empire and levied repressive taxes on the Armenian inhabitants. After Catholicos Gregory II the Martyrophile's assistant and representative, Parsegh of Cilicia's solicitation, the Armenians obtained a partial reprieve, but Malik's succeeding governors continued levying taxes.[12] This led the Armenians to seek refuge in Byzantium and in Cilicia. Some Armenian leaders set themselves up as sovereign lords, while others remained, at least in name, loyal to the Empire. The most successful of these early Armenian warlords was Philaretos Brachamios, a former Byzantine general who was alongside Romanus Diogenes at Manzikert. Between 1078 and 1085, Philaretus built a principality stretching from Malatia in the north to Antioch in the south, and from Cilicia in the west to Edessa in the east. He invited many Armenian nobles to settle in his territory, and gave them land and castles.[15] But Philaretus's state began to crumble even before his death in 1090, and ultimately disintegrated into local lordships.[16]

The Rubenid dynasty

editEmergence of Cilician Armenia

editOne of the princes who came after Philaretos' invitation was Ruben, who had close ties with the last Bagratid Armenian king, Gagik II. Ruben was alongside the Armenian ruler Gagik when he went to Constantinople upon the Byzantine emperor's request. Instead of negotiating peace, however, the king was forced to cede his Armenian lands and live in exile. Gagik was later assassinated by Greeks.[17] In 1080, soon after this assassination, Ruben organized a band of Armenian troops and revolted against the Byzantine Empire.[18] He was joined by many other Armenian lords and nobles. Thus, in 1080, the foundations of the independent Armenian princedom of Cilicia, and the future kingdom, were laid under Ruben's leadership.[5] His descendants were called Rubenids[13] (or Rubenians). After Ruben's death in 1095, the Rubenid principality, centered around their fortresses, was led by Ruben's son, Constantine I of Armenia; however, there were several other Armenian principalities both inside and beyond Cilicia, such as that of the Het'umids. This important Armenian dynasty was founded by the former Byzantine general Oshin, and was centered southwest of the Cilician Gates.[16] The Het'umids contended with the Rubenids for power and influence over Cilicia. Various Armenian lords and former generals of Philaretos were also present in Marash, Malatia (Melitene), and Edessa, the latter two being located outside Cilicia.[16]

First Crusade

editDuring the reign of Constantine I, the First Crusade took place. An army of Western European Christians marched through Anatolia and Cilicia on their way to Jerusalem. The Armenians in Cilicia gained powerful allies among the Frankish Crusaders, whose leader, Godfrey of Bouillon, was considered a savior for the Armenians. Constantine saw the Crusaders' arrival as a one-time opportunity to consolidate his rule of Cilicia by eliminating the remaining Byzantine strongholds in the region.[18] With the Crusaders' help, they secured Cilicia from the Byzantines and Turks, both by direct military actions in Cilicia and by establishing Crusader states in Antioch, Edessa, and Tripoli.[19] The Armenians also helped the Crusaders; as described by Pope Gregory XIII in his Ecclesia Romana:

Among the good deeds which the Armenian people has done towards the church and the Christian world, it should especially be stressed that, in those times when the Latin Christian princes and the warriors went to retake the Holy Land, no people or nation, with the same enthusiasm, joy and faith came to their aid as the Armenians did, who supplied the Crusaders with horses, provision and guidance. The Armenians assisted these warriors with their utter courage and loyalty during the Holy wars.

To show their appreciation to their Armenian allies, the Crusaders honored Constantine with the titles of Comes and Baron. The friendly relationship between the Armenians and Crusaders was cemented by frequent intermarriages. For instance, Joscelin I of Edessa married the daughter of Constantine, and Baldwin, brother of Godfrey, married Constantine's niece, daughter of his brother T'oros.[18] The Armenians and Crusaders were part allies, part rivals for the two centuries to come. Often at the invitation of Armenian barons and kings the Crusaders maintained for varying periods castles in and along the borders of the Kingdom, including Bagras, Trapessac, T‛il Hamtun, Harunia, Selefkia, Amouda, and Sarvandikar.[5]

Armenian-Byzantine and Armenian-Seljuk contentions

editThe son of Constantine was Thoros I, who succeeded him in around 1100. During his rule, he faced both Byzantines and Seljuks, and expanded the Rubenid domain. He transferred the Cilician capital from Tarsus to Sis after having eliminated the small Byzantine garrison stationed there.[20] In 1112, he took the castle of Cyzistra in order to avenge the death of the last Bagratid Armenian king, Gagik II. The assassins of the latter, three Byzantine brothers who governed the castle, were thus brutally killed.[18][19] Eventually, there emerged a type of centralized government in the area with the rise of the Rubenid princes. During the twelfth century, they were the closest thing to a ruling dynasty, and wrestled with the Byzantines for power over the region.

Prince Levon I, T'oros' brother and successor, started his reign in 1129. He integrated the Cilician coastal cities to the Armenian principality, thus consolidating Armenian commercial leadership in the region. During this period, there was continued hostility between Cilician Armenia and the Seljuk Turks, as well as occasional bickering between Armenians and the Principality of Antioch over forts located near southern Amanus.[18] In this context, in 1137, the Byzantines under Emperor John II, who still considered Cilicia to be a Byzantine province, conquered most of the towns and cities located on the Cilician plains.[18][19] They captured and imprisoned Levon in Constantinople with several other family members, including his sons Ruben and T'oros. Levon died in prison three years later.[19] Ruben was blinded and killed while in prison, but Levon's second son and successor, Thoros II, escaped in 1141 and returned to Cilicia to lead the struggle with the Byzantines.[18] Initially, he was successful in repelling Byzantine invasions; but, in 1158, he paid homage to Emperor Manuel I through a short-lived treaty.[21] Around 1151, during T'oros' rule, the head of the Armenian Church transferred his see to Hromkla.[14] Ruben II, Mleh, and Ruben III, succeeded T'oros in 1169, 1170, and 1175, respectively.

Principality becomes a kingdom

editThe Principality of Cilicia was a de facto kingdom before the ascension of Levon II. Levon II is considered the first king of Cilicia due to the Byzantine refusal of previous de facto kings as genuine de jure kings, rather than dukes.

Prince Levon II, one of Levon I's grandsons and brother of Ruben III, acceded the throne in 1187. He fought the Seljuks of Iconium, Aleppo, and Damascus, and added new lands to Cilicia, doubling its Mediterranean coast.[22] At the time, Saladin of Egypt defeated the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which led to the Third Crusade. Prince Levon II profited from the situation by improving relations with the Europeans. Cilician Armenia's prominence in the region is attested by letters sent in 1189 by Pope Clement III to Levon and to Catholicos Gregory IV, in which he asks Armenian military and financial assistance to the crusaders.[7] Thanks to the support given to Levon by the Holy Roman Emperors (Frederick Barbarossa, and his son, Henry VI), he elevated the princedom's status to a kingdom. On January 6, 1198, the day Armenians celebrate Christmas, Prince Levon II was crowned with great solemnity in the cathedral of Tarsus, in the presence of the Syrian Jacobite patriarch, the Greek metropolitan of Tarsus, and numerous church dignitaries and military leaders.[23] While he was crowned by the catholicos, Gregory VI Abirad, Levon received a banner with the insignia of a lion from Archbishop Conrad of Mainz in the name of Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor.[7][24] By securing his crown, he became the first King of Armenian Cilicia as King Levon I.[22] He became known as Levon the Magnificent, due to his numerous contributions to Cilician Armenian statehood in the political, military, and economic spheres.[5] Levon's growing power made him a particularly important ally for the neighbouring crusader state of Antioch, which resulted in intermarriage with noble families there, but his dynastic policies revealed ambition towards the overlordship of Antioch which the Latins ultimately could not countenance. They resulted in the Antiochene Wars of Succession between Levon's grand-nephew Raymond Roupen and Bohemond IV of Antioch-Tripoli.[25] The Rubenids consolidated their power by controlling strategic roads with fortifications that extended from the Taurus Mountains into the plain and along the borders, including the baronial and royal castles at Sis, Anavarza, Vahka, Vaner/Kovara, Sarvandikar, Kuklak, T‛il Hamtun, Hadjin, and Gaban (modern Geben).[5]

In 1219, after a failed attempt by Raymond-Roupen to claim the throne, Levon's daughter Zabel was proclaimed the new ruler of Cilician Armenia and placed under the regency of Adam of Baghras. Baghras was assassinated and the regency passed to Constantine of Baberon from the Het'umid dynasty, a very influential Armenian family.[8] In order to fend off the Seljuk threat, Constantine sought an alliance with Bohemond IV of Antioch, and the marriage of Bohemond's son Philip to Queen Zabel sealed this; however, Philip was too "Latin" for the Armenians' taste, as he refused to abide by the precepts of the Armenian Church.[8] In 1224, Philip was imprisoned in Sis for stealing the crown jewels of Armenia, and after several months of confinement, he was poisoned and killed. Zabel decided to embrace a monastic life in the city of Seleucia, but she was later forced to marry Constantine's son Het'um in 1226.[8] Het'um became co-ruler as King Het'um I.

The Het'umid dynasty

editBy the 11th century the Het‘umids had settled into western Cilicia, primarily in the highlands of the Taurus Mountains. Their two great dynastic castles were Lampron and Papeŕōn/Baberon, which commanded strategic roads to the Cilician Gates and to Tarsus.[5]

The apparent unification in marriage of the two main dynasties of Cilicia, Rubenid and Het'umid, ended a century of dynastic and territorial rivalry, while bringing the Het'umids to the forefront of political dominance in Cilician Armenia.[8] Although the accession of Het'um I in 1226 marked the beginning of Cilician Armenia's united dynastic kingdom, the Armenians were confronted by many challenges from abroad. In order to enact revenge for his son's death, Bohemond sought an alliance with Seljuk sultan Kayqubad I, who captured regions west of Seleucia. Het'um also struck coins with his figure on one side, and with the name of the sultan on the other.[8]

Armeno-Mongol alliance and Mamluk threat

editDuring the rule of Zabel and Het'um, the Mongols under Genghis Khan and his successor Ögedei Khan rapidly expanded from Central Asia and reached the Middle East, conquering Mesopotamia and Syria in their advance towards Egypt.[8] On June 26, 1243, they secured a decisive victory at Köse Dağ against the Seljuk Turks.[27] The Mongol conquest was disastrous for Greater Armenia, but not Cilicia, as Het'um preemptively chose to cooperate with the Mongols. He sent his brother Smbat to the Mongol court of Karakorum in 1247 to negotiate an alliance.[a][b][c] He returned in 1250 with an agreement guaranteeing the integrity of Cilicia, as well as the promise of Mongol aid to recapture forts seized by the Seljuks. Despite his sometimes-burdensome military commitments to the Mongols, Het’um had the financial resources and political autonomy to build new and impressive fortifications, such as the castle at Tamrut.[28] In 1253, Het'um himself visited the new Mongol ruler Möngke Khan at Karakorum. He was received with great honors and promised freedom from taxation of the Armenian churches and monasteries located in Mongol territory.[7] Both during his trip to the Mongol court and in his 1256 return to Cilicia, he passed through Greater Armenia. On his return voyage, he remained much longer, receiving visits from local princes, bishops, and abbots.[7] Het'um and his forces fought under the Mongol banner of Hulagu in the conquest of Muslim Syria and the capture of Aleppo and Damascus from 1259 to 1260. The involvement of Het'um at these two conquests is debated however, with the source for such information - Templar of Tyre - claiming his involvement in a deliberate attempt to integrate Mongols into a Holy-War conquest narrative. This was to persuade Latin Christendom of the need for a war against the Mamluks. [29] According to Arab historians, during Hulagu's conquest of Aleppo, Het'um and his forces were responsible for a massacre and arsons in the main mosque and in the neighboring quarters and souks.[27]

Meanwhile, the Egyptian Mamluks had been replacing their former Ayyubid masters in Egypt. The Mamluks began as a cavalry corps established from Turkic and other slaves sold to the Egyptian sultan by Genghis Khan.[30] They took control of Egypt and Palestine in 1250 and 1253, respectively, and filled the vacuum caused by the Mongol destruction of the pre-existing Ayyubid and Abbasid governments.[27] Cilician Armenia also expanded and recovered lands crossed by important trade routes on the Cappadocian, Mesopotamian, and Syrian borders, including Marash and Behesni, which further made the Armenian Kingdom a potential Mamluk target.[27] Armenia also engaged in an economic battle with the Mamluks for control of the spice trade.[31] The Mamluk leader Baibars took the field in 1266 with the intention of wiping out the Crusader states from the Middle East.[30] In the same year, he summoned Het'um I to change his allegiance from the Mongols to the Mamluks, and remit to the Mamluks the territories and fortresses the Armenian king had acquired through his submission to the Mongols. After these threats, Het'um went to the Mongol court of the Il-Khan in Persia to obtain military support, but in his absence, the Mamluks invaded Cilician Armenia. Het'um's sons T'oros and Levon were left to defend the country. During the Disaster of Mari, the Mamluks under Sultan Al-Mansur Ali and the commander Qalawun overran the heavily outnumbered Armenians, killing T'oros and capturing Levon. Afterwards the capital of Sis was sacked and burnt, thousands of Armenians were massacred and 40,000 taken captive.[32] Het'um ransomed Levon for a high price, giving the Mamluks control of many fortresses and a large sum of money. The 1269 Cilicia earthquake further devastated the country.

In 1269, Het'um I abdicated in favour of his son Levon II, who paid large annual tributes to the Mamluks. Even with the tributes, the Mamluks continued to attack Cilicia every few years. In 1275, an army led by the emirs of the sultan invaded the country without pretext and faced Armenians who had no means of resistance. The city of Tarsus was taken, the royal palace and the church of Saint Sophia was burned, the state treasury was looted, 15,000 civilians were killed, and 10,000 were taken captive to Egypt. Almost the entire population of Ayas, Armenian, and Frankish perished.[30]

Truce with Mamluks (1281–1295)

editIn 1281, following the defeat of the Mongols and the Armenians under Möngke Temur by the Mamluks at the Second Battle of Homs, a truce was forced on Armenia. Further, in 1285, following a powerful offensive push by Qalawun, the Armenians had to sign a ten-year truce under harsh terms. The Armenians were obligated to cede many fortresses to the Mamluks and were prohibited to rebuild their defensive fortifications. Cilician Armenia was forced to trade with Egypt, thereby circumventing a trade embargo imposed by the pope. Moreover, the Mamluks were to receive an annual tribute of one million dirhams from the Armenians.[33] The Mamluks, despite the above, continued to raid Cilician Armenia on numerous occasions. In 1292, it was invaded by Al-Ashraf Khalil, the Mamluk sultan of Egypt, who had conquered the remnants of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in Acre the year before. Hromkla was also sacked, forcing the Catholicossate to move to Sis. Het'um was forced to abandon Behesni, Marash, and Tel Hamdoun to the Turks. In 1293, he abdicated in favor of his brother T'oros III, and entered the monastery of Mamistra.

Campaigns with Mongols (1299–1303)

editIn the summer of 1299, Het'um I's grandson, King Het'um II, again facing threats of attack by the Mamluks, asked the Mongol khan of Persia, Ghâzân, for his support. In response, Ghâzân marched towards Syria and invited the Franks of Cyprus (the King of Cyprus, the Templars, the Hospitallers, and the Teutonic Knights), to join his attack on the Mamluks. The Mongols took the city of Aleppo, where they were joined by King Het'um. His forces included Templars and Hospitallers from the kingdom of Armenia, who participated in the rest of the offensive.[35] The combined force defeated the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar, on December 23, 1299.[35] The bulk of the Mongol army was then obligated to retreat. In their absence, the Mamluks regrouped, and regained the area in May 1300.

In 1303, the Mongols tried to conquer Syria once again in larger numbers (approximately 80,000) along with the Armenians, but they were defeated at Homs on March 30, 1303, and during the decisive Battle of Shaqhab, south of Damascus, on April 21, 1303.[36] It is considered to be the last major Mongol invasion of Syria.[37] When Ghazan died on May 10, 1304, all hope of reconquest of the Holy Land died in conjunction.

Het'um II abdicated in favour of his sixteen-year-old nephew Levon III and became a Franciscan friar; however, he emerged from his monastic cell to help Levon defend Cilicia from a Mamluk army, which was thus defeated near Baghras.[38] In 1307, both the current and former kings met with Bularghu, the Mongol representative in Cilicia, at his camp just outside Anazarba. Bularghu, a recent convert to Islam, murdered the entire Armenian party.[39] Oshin, brother of Het'um, immediately marched against Bularghu to retaliate and vanquished him, forcing him to leave Cilicia. Bulargu was executed by Oljeitu for his crime at the request of the Armenians.[40] Oshin was crowned new king of Cilician Armenia upon his return to Tarsus.[38]

The Het'umids continued ruling an unstable Cilicia until the assassination of Levon IV in 1341, at the hands of an angry mob. Levon IV formed an alliance with the Kingdom of Cyprus, then ruled by the Frankish Lusignan dynasty, but could not resist attacks from the Mamluks.[41]

Demise of Cilician Armenia

editDecline and fall with the Lusignan dynasty

editThere had always been close relations between the Armenians and the Lusignans, who, by the 12th century, were already established in the eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus. Had it not been for their presence in Cyprus, the kingdom of Cilician Armenia may have, out of necessity, established itself on the island.[45] In 1342, Levon's cousin Guy de Lusignan, was anointed king as Constantine II, King of Armenia. Guy de Lusignan and his younger brother John were considered pro-Latin and deeply committed to the supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church in the Levant. As kings, the Lusignans attempted to impose Catholicism and the European ways. The Armenian nobles largely accepted this, but the peasantry opposed the changes, which eventually led to civil strife.[46]

From 1343 to 1344, a time when the Armenian population and its feudal rulers refused to adapt to the new Lusignan leadership and its policy of Latinizing the Armenian Church, Cilicia was again invaded by the Mamluks, who were intent on territorial expansion.[47] Frequent appeals for help and support were made by the Armenians to their co-religionists in Europe, and the kingdom was also involved in planning new crusades.[48] Amidst failed Armenian pleas for help from Europe, the fall of Sis to the Mamluks, followed by the fortress of Gaban in 1375, where King Levon V, his daughter Marie, and her husband Shahan had taken refuge, put an end to the kingdom.[47] The final king, Levon V, was granted safe passage and arrived in Castille seeking assistance from the King John I of Castile to recover his kingdom. While in Castille, he was granted the title of Lord of Madrid and other cities. He left Castille for France at the death of John I and died in exile in Paris in 1393, after having called in vain for another crusade.[46] In 1396, Levon's title and privileges were transferred to James I, his cousin and king of Cyprus. The title of King of Armenia was thus united with the titles of King of Cyprus and King of Jerusalem.[49] The title has also been claimed indirectly by the House of Savoy by claiming the title King of Jerusalem and a number of other thrones.[citation needed]

Dispersion of the Armenian population of Cilicia

editAlthough the Mamluks had taken over Cilicia, they were unable to hold it. Turkic tribes settled there, leading to the conquest of Cilicia led by Timur. As a result, 30,000 wealthy Armenians left Cilicia and settled in Cyprus, still ruled by the Lusignan dynasty until 1489.[46] Many merchant families also fled westward and founded or joined with existing diaspora communities in France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain.[9] Only the humbler Armenians remained in Cilicia. They nevertheless maintained their foothold in the region throughout Turkic rule.

In the 16th century, Cilicia fell under Ottoman dominion and officially became known as the Adana Vilayet in the 17th century. Cilicia was one of the most important regions for the Ottoman Armenians, because it managed to preserve Armenian character well throughout the years.[9][50] In 1909, Cilician Armenians were massacred in Adana.[50] Descendants of the remaining Cilician Armenians have been dispersed in the Armenian diaspora, and the Holy See of Cilicia is based in Antelias, Lebanon. The lion, emblem of the Cilician Armenian state, remains a symbol of Armenian statehood to this day, featured on the Coat of arms of Armenia.

Cilician Armenian society

editCulture

editDemographically, Cilician Armenia was heterogeneous with a population of Armenians who constituted the ruling class, and also Greeks, Jews, Muslims, and various Europeans.[51] The multi-ethnic population, as well as commercial and political links with Europeans, particularly France, brought important new influences on Armenian culture.[51] The Cilician nobility adopted many aspects of Western European life, including chivalry, fashion, and the use of French Christian names. The structure of Cilician society became more synonymous with Western feudalism than to the traditional nakharar system of Armenia.[9] In fact, during the Cilician period, Western titles such as baron and constable replaced their Armenian equivalents nakharar and sparapet.[9][51] European tradition was adopted for the knighting of Armenian nobles, while jousts and tournaments similar to those in Europe had become popular in Cilician Armenia. The extent of Western influence over Cilician Armenia is also reflected by the incorporation of two new letters (Ֆ ֆ = "f" and Օ օ = "o") and various Latin-based words into the Armenian language.[51]

In other areas, there was more hostility to the new Western trends. Above all, most ordinary Armenians frowned on conversion to Roman Catholicism or Greek Orthodoxy. Cultural influence was not merely one-way, however; Cilician Armenians had an important impact on Crusaders returning to the West, most notably with their architectural traditions. Europeans incorporated elements of Armenian castle-building, learned from Armenian masons in the Crusader states, as well as some elements of church architecture.[10] Most Armenian castles made atypical usage of rocky heights, and featured curved walls and round towers, similar to those of the Hospitaller castles Krak des Chevaliers and Marqab.[52] The Cilician period also produced some important examples of Armenian art, notably the illuminated manuscripts of Toros Roslin, who was at work in Hromkla in the thirteenth century.[9]

Economy

editCilician Armenia had become a prosperous state due to its strategic position on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. It was located at the juncture of many trade routes linking Central Asia and the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. The kingdom was thus important in the spice trade, as well as livestock, hides, wool, and cotton. In addition, important products such as timber, grain, wine, raisins, and raw silk were also exported from the country and finished cloth and metal products from the West were made available.[9]

During the reign of King Levon, the economy of Cilician Armenia progressed greatly and became heavily integrated with Western Europe. He secured agreements with Pisa, Genoa, and Venice, as well as the French and the Catalans, and granted them certain privileges such as tax exemptions in return for their business. The three primary harbours of the Armenian Kingdom, which were vital to its economy and defense, were the fortified coastal sites at Ayas and Korikos, and the river emporium of Mopsuestia. The latter, situated on two strategic caravan routes, was the last fully navigable port to the Mediterranean on the Pyramus River and the location of warehouses licensed by the Armenians to the Genoese.[5] Important European merchant communities and colonies came into existence, with their own churches, courts of law, and trading houses.[53] As French became the secondary language of Cilician nobility, the secondary language for Cilician commerce had become Italian due to the three Italian city-states' extensive involvement in the Cilician economy.[9] Marco Polo, for example, set out on his journey to China from Ayas in 1271.[53]

In the thirteenth century, under the rule of Toros, Cilician Armenia already struck its own coins. Gold and silver coins, called dram and tagvorin, were struck at the royal mints of Sis and Tarsus. Foreign coins such as the Italian ducat, florin, and zecchino, the Greek besant, the Arab dirham, and the French livre were also accepted by merchants.[9]

Religion

editThe Catholicosate of the Armenian Apostolic Church followed its people in taking refuge outside the Armenian highlands, which had turned into a battleground of Byzantine and Seljuk contenders. Its seat was first transferred to Sebasteia in 1058 in Cappadocia, where had existed a significant Armenian population. Later, it moved to various locations in Cilicia; Tavbloor in 1062; Dzamendav in 1066; Dzovk in 1116; and Hromkla in 1149. During King Levon I's rule, the Catholicos was located in distant Hromkla. He was assisted by fourteen bishops in administering the Armenian Church in the kingdom, a number which grew in later years. The archbishops' seats were located in Tarsus, Sis, Anazarba, Lambron, and Mamistra. There existed up to sixty monastic houses in Cilicia, although the exact locations of the majority of them remain unclear.[9]

In 1198, the Catholicos of Sis, Grigor VI Apirat, proclaimed a union between the Armenian Church and the Roman Catholic Church; however, this had no notable effect, as the local clergy and populace was strongly opposed to such a union. The Western Church sent numerous missions to Cilician Armenia to help with rapprochement, but had limited results. The Franciscans were put in charge of this activity. John of Monte Corvino himself arrived in Cilician Armenia in 1288.[54]

Het'um II became a Franciscan friar after his abdication. The Armenian historian Nerses Balients was a Franciscan and an advocate of union with the Latin Church. The papal claim of primacy did not contribute positively to the efforts for unity between the Churches.[55] Mkhitar Skewratsi, the Armenian delegate at the council in Acre in 1261, summed the Armenian frustration in these words:

Whence does the Church of Rome derive the power to pass judgment on the other Apostolic sees while she herself is not subject to their judgments? We ourselves [the Armenians] have indeed the authority to bring you [the Catholic Church] to trial, following the example of the Apostles, and you have no right to deny our competency.[55]

After the sacking of Hromkla by the Mamluks in 1293, the Catholicosate was transferred to Sis, the capital of the Cilician Kingdom. Again, in 1441, long after the fall of the kingdom, the Armenian Catholicos of Sis, Grigor IX Musabekiants, proclaimed the union of the Armenian and Latin churches at the Council of Florence; this was countered by an Armenian schism under Kirakos I Virapetsi, who moved the See of the Catholicos to Echmiadzin, and marginalized Sis.[56]

See also

editExplanatory notes

edit- a Claude Mutafian in Le Royaume Arménien de Cilicie, p. 55, describes "the Mongol alliance" entered into by the king of Armenia and the Franks of Antioch ("the King of Armenia decided to engage into the Mongol alliance, an intelligence that the Latin barons lacked, except for Antioch"), and "the Franco-Mongol collaboration."

- b Claude Lebedel in Les Croisades describes the alliance of the Franks of Antioch and Tripoli with the Mongols: (in 1260) "the Frank barons refused an alliance with the Mongols, except for the Armenians and the Prince of Antioch and Tripoli".

- c Amin Maalouf in The Crusades through Arab eyes is extensive and specific on the alliance (page numbers refer to the French edition): “The Armenians, in the person of their king Hetoum, sided with the Mongols, as well as Prince Bohemond, his son-in-law. The Franks of Acre however adopted a position of neutrality favourable to the muslims” (p. 261), “Bohemond of Antioch and Hethoum of Armenia, principal allies of the Mongols” (p. 265), “Hulagu (…) still had enough strength to prevent the punishment of his allies [Bohemond and Hethoum]” (p. 267).

Citations

edit- ^ Ghazarian, Jacob (2018). The Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia During the Crusades: The Integration of Cilician Armenians with the Latins, 1080-1393. Routledge. ISBN 9781136124181.

- ^ a b Bornozyan, S. V.; Zulalyan, Manvel [in Armenian] (1976). Հայ Ժողովրդի Պատմություն, Հ. 3. [History of the Armenian People. Vol. 3] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences. pp. 672, 724.

Կիլիկյան հայկական պետության ծաղկան ժամանակաշրջանում՝ XIII դարում, նրա տարածությունը կազմում էր 40.000 քառ. կմ, իսկ բնակչության թիվը անցնում էր մեկ միլիոնից։ [...] Կիլիկիայի քաղաքներում ու նավահանգիստներում էր կենտրոնացված Կիլիկիայի մեկ միլիոն բնակչության համարյա կեսը։

- ^ "Landmarks in Armenian history". Internet Archive. Retrieved June 22, 2010. "1080 A.D. Rhupen, cousin of the Bagratonian kings, sets up on Mount Taurus (overlooking the Mediterranean Sea) the kingdom of New Armenia which lasts 300 years."

- ^ Der Nersessian, Sirarpie (1969) [1962]. "The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Wolff, Robert Lee; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Later Crusades, 1189–1311 (Second ed.). Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 630–659. ISBN 0-299-04844-6., pp. 630–631.

- ^ a b c d e f g Edwards, Robert W. (1987). The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia, Dumbarton Oaks Studies No.23. Washington D. C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. pp. vii–xxxi, 3–288. ISBN 0884021637.

- ^ Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Պատմութիւն Հայոց [History of Armenia] (in Armenian). Vol. II. Athens: Հրատարակութիւն ազգային ուսումնակաան խորհուրդի [Council of National Education Publishing]. pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c d e f Der Nersessian. "The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia", pp. 645–653.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghazarian, Jacob G. (2000). The Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia during the Crusades: The Integration of Cilician Armenians with the Latins (1080–1393). Routledge. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-7007-1418-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bournoutian, Ani Atamian. "Cilician Armenia" in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997, pp. 283–290. ISBN 1-4039-6421-1.

- ^ a b "Cilician Kingdom". Globe Weekly News. Archived from the original on 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

- ^ "King Tigran II – The Great". Hye Etch. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghazarian, Jacob G. (2000). The Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia during the Crusades: The Integration of Cilician Armenians with the Latins (1080–1393). Routledge. pp. 39–42. ISBN 0-7007-1418-9.

- ^ a b Dédéyan, Gérard (2008). "The Founding and the Coalescence of the Rubenian Principality, 1073–1129". In Hovannisian, Richard G.; Payaslian, Simon (eds.). Armenian Cilicia. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series 8. United States: Mazda Publishers. pp. 79–83. ISBN 978-1-56859-154-4.

- ^ a b c Donal Stewart, Angus (2001). The Armenian Kingdom and the Mamluks: War and Diplomacy During the Reigns of Het'um II (1289–1307). Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-90-04-12292-5.

- ^ Bozoyan, Azat A. (2008). "Armenian Political Revival in Cilicia". In Hovannisian, Richard G.; Payaslian, Simon (eds.). Armenian Cilicia. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series. United States: Mazda Publishers. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-56859-154-4.

- ^ a b c Runciman, Steven (1951). A History of the Crusades, Vol. I: The First Crusade and the Foundations of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 195–201. ISBN 0-521-35997-X.

- ^ Kurkdjian, Vahan (1958). "Chapter XXV: Magnificence to be soon followed by Calamity". History of Armenia. United States of America: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 202.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kurkdjian, Vahan (1958). "Chapter XXVII: The Barony of Cilician Armenia". History of Armenia. United States of America: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. pp. 213–226.

- ^ a b c d Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Պատմութիւն Հայոց (History of Armenia), Volume II (in Armenian). Athens: Հրատարակութիւն ազգային ուսումնակաան խորհուրդի (Council of National Education Publishing). pp. 33–36.

- ^ Runciman, Steven. A History of the Crusades – Volume II.: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East: 1100–1187.

- ^ Ghazarian, Jacob G. (2000). The Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia during the Crusades: The Integration of Cilician Armenians with the Latins (1080–1393). Routledge. pp. 118–120. ISBN 0-7007-1418-9.

- ^ a b Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Պատմութիւն Հայոց (History of Armenia), Volume II (in Armenian). Athens: Հրատարակութիւն ազգային ուսումնակաան խորհուրդի (Council of National Education Publishing). pp. 42–44.

- ^ The letter of love and concord : a revised diplomatic edition with historical and textual comments and English translation. Pogossian, Zaroui. Leiden: Brill. 2010. p. 17, note 46. ISBN 978-90-04-19189-1. OCLC 729872723.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Nickerson Hardwicke, Mary. The Crusader States, 1192–1243.

- ^ Natasha Hodgson, Conflict and Cohabitation Marriage and Diplomacy between Latins and Cilician Armenians c. 1150-1254’ in The Crusades and the Near East, ed. C Kostick (Routledge, 2010)

- ^ "Hethoum I receiving the homage of the Tatars: during his voyage to Mongolia in 1254, Hethoum I was received with honours by the Mongol Khan who 'ordered several of his noble subjects to honour and attend him'" in Claude Mutafian, Le Royaume Armenien de Cilicie, p.58, quoting Hayton of Corycus.

- ^ a b c d Donal Stewart, Angus (2001). The Armenian Kingdom and the Mamluks: War and Diplomacy During the Reigns of Het'um II (1289–1307). Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 43–46. ISBN 978-90-0412292-5.

- ^ Christianian, Jirair, “The Inscription at Tamrut Castle: The Case for a Revision of Armenian History,” Le Muséon 132 (1-2), 2019, pp.107-122.

- ^ "The king of Armenia and the Prince of Antioch went to the military camp of the Tatars, and they all went off to take Damascus". Le Templier de Tyr. Quoted in Rene Grousset, Histoire des Croisade, III, p. 586.

- ^ a b c Kurkdjian, Vahan (1958). "Chapter XXX: The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia — Mongol Invasion". History of Armenia. United States of America: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. pp. 246–248.

- ^ Luscombe, David; W. Hazard, Harry (2004). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV: c. 1024-c. 1198. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 634. ISBN 0-521-41411-3.

- ^ Chahin, Mack (2001). The Kingdom of Armenia: A History. Richmond: Curzon. p. 253. ISBN 0700714529.

- ^ Luisetto, Frédéric (2007). Arméniens et autres Chrétiens d'Orient sous la domination mongole (in French). Geuthner. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-2-7053-3791-9.

- ^ Mutafian, Claude (2002). Le Royaume Arménien de Cilicie, XIIe-XIVe siècle. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series (in French). France: CNRS Editions. pp. 74–75. ISBN 2-271-05105-3.

- ^ a b Demurger, Alain (2005). The Last Templar: The Tragedy of Jacques de Molay, Last Grand Master of the Temple. London: Profile Books. p. 93. ISBN 1-86197-529-5.

- ^ Demurger, Alain (2005). The Last Templar: The Tragedy of Jacques de Molay, Last Grand Master of the Temple. London: Profile Books. p. 109. ISBN 1-86197-529-5.

- ^ Nicolle, David (2001). The Crusades. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 1-84176-179-6.

- ^ a b Kurkdjian, Vahan (1958). "Chapter XXX: The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia — Mongol Invasion". History of Armenia. United States of America: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. pp. 253–254.

- ^ Angus, Stewart, "The assassination of King Het'um II". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 2005 pp. 45–61.

- ^ (in French) Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Documents Armeniens I, p.664

- ^ Mahé, Annie; Mahé, Jean-Pierre (2005). L'Arménie à l'épreuve des Siècles (in French). France: Découvertes Gallimard. p. 77. ISBN 2-07-031409-X.

- ^ Massing, Jean Michel (1 January 1991). Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Yale University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-300-05167-4.

The Cilician kingdom of Armenia Minor is more clearly indicated. Founded at the end of the twelfth century, it fell to the Turks in 1375

- ^ Galichian, Rouben (2014). Historic Maps of Armenia - The Cartographic Heritage. Abridged and updated. BENNETT & BLOOM. p. 59.

- ^ Massing, Jean Michel (1991). "Observations and Beliefs: The World of the Catalan Atlas". In Levenson, Jay A. (ed.). Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Yale University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-300-05167-4.

The Catalan map does not make much of Ottoman power. The Cilician kingdom of Armenia Minor is more clearly indicated. Founded at the end of the twelfth century, it fell to the Turks in 1375, the very year in which the Atlas was made.8

- ^ Ghazarian, Jacob G. (2000). The Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia during the Crusades: The Integration of Cilician Armenians with the Latins (1080–1393). Routledge. p. 150. ISBN 0-7007-1418-9.

- ^ a b c Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Պատմութիւն Հայոց (History of Armenia), Volume II (in Armenian). Athens: Հրատարակութիւն ազգային ուսումնակաան խորհուրդի (Council of National Education Publishing). pp. 53–56.

- ^ a b Ghazarian, Jacob G. (2000). The Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia during the Crusades: The Integration of Cilician Armenians with the Latins (1080–1393). Routledge. pp. 159–161. ISBN 0-7007-1418-9.

- ^ Housley, Norman (1992). The later Crusades, 1 274-1580: from Lyons to Alcazar. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-19-822136-3.

- ^ Hadjilyra, Alexander-Michael (2009). The Armenians of Cyprus. New York: Kalaydjian Foundation. p. 12.

- ^ a b Bryce, Viscount (2008). The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Germany: Textor Verlag. pp. 465–467. ISBN 978-3-938402-15-3.

- ^ a b c d Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: from kings and priests to merchants and commissars. London: Columbia University Press. pp. 63–66. ISBN 978-0-231-13926-7.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh N. (2006). Muslim military architecture in greater Syria: from the coming of Islam to the Ottoman Period. Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. p. 293. ISBN 978-90-04-14713-3.

- ^ a b Abulafia, David (1999). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge University Press. p. 440. ISBN 0-521-36289-X.

- ^ Luisetto. Arméniens et autres Chrétiens, p. 98.

- ^ a b Parry, Ken (2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing ltd. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-631-23423-4.

- ^ Mahé, Annie; Mahé, Jean-Pierre (2005). L'Arménie à l'épreuve des Siècles. Découvertes Gallimard (in French). Vol. 464. France: Gallimard. pp. 71–72. ISBN 2-07-031409-X.

Further reading

edit- (In Armenian) Poghosyan, S.; Katvalyan, M.; Grigoryan, G. et al. «Կիլիկյան [sic] Հայաստան» ("Cilician Armenia") Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. vol. V. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1979, pp. 406–428.

- Boase, T. S. R. (1978). The Cilician Kingdom of Armenia. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. ISBN 0-7073-0145-9.

- Ghazarian, Jacob G. (2000). The Armenian kingdom in Cilicia during the Crusades. Routledge. p. 256. ISBN 0-7007-1418-9.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. and Simon Payaslian (eds.) Armenian Cilicia. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series: Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, 7. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2008.

- Luisetto, Frédéric (2007). Arméniens et autres Chrétiens d'Orient sous la domination Mongole. Geuthner. p. 262. ISBN 978-2-7053-3791-9.

- Mahé, Jean-Pierre. L'Arménie à l'épreuve des siècles, coll. Découvertes Gallimard (n° 464), Paris: Gallimard, 2005, ISBN 978-2-07-031409-6

- William Stubbs (1886). "The Medieval Kingdoms of Cyprus and Armenia: (Oct. 26 and 29, 1878.)". Seventeen lectures on the study of medieval and modern history and kindred subjects: 156–207. Wikidata Q107247875.

External links

edit- Cilician Armenian Coins Archived 2021-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kilikia" song with lyrics Archived 2011-06-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Cilician Armenian Architecture