Islam began to make inroads into the Armenian plateau during the seventh century. Arab, and later Kurdish, tribes began to settle in Armenia following the first Arab invasions and played a considerable role in the political and social history of Armenia.[2] With the Seljuk invasions of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Turkic element eventually superseded that of the Arab and Kurdish. With the establishment of the Iranian Safavid dynasty, Afsharid dynasty, Zand dynasty and Qajar dynasty, Armenia became an integral part of the Shia world, while still maintaining a relatively independent Christian identity. The pressures brought upon the imposition of foreign rule by a succession of Muslim states forced many lead Armenians in Anatolia and what is today Armenia to convert to Islam and assimilate into the Muslim community. Many Armenians were also forced to convert to Islam, on the penalty of death, during the years of the Armenian Genocide.[3]

History

editFirst Armenian Muslims

editFarqad Sabakhi (died 729 AD) was an Armenian Muslim preacher and a companion of Hassan Basri's.[2][page needed] As a result, he is considered one of the Tabi'in (the next generation of companions). Farqad Sabakhi was originally a Christian. Farqad Sabakhi probably raised the famous Karkhi, who played a pivotal role in shaping Sufism. Sabakhi was known for his ascetic life and knowledge of the Judeo-Christian scriptures.[4]

Arab invasions

editThe Muslim Arabs first invaded Armenia in 639, under the leadership of Abd ar-Rahman ibn Rabiah, 18,000 Arabs penetrated the district of Taron and the region of the Lake of Van.[5][unreliable source?] Prince Theodoros Rshtuni led the Armenian defense. In about 652, a peace agreement was made, allowing Armenians freedom of religion. Prince Theodoros traveled to Damascus, where he was recognized by the Arabs as the ruler of Armenia, Georgia and Caucasian Albania.[6]

By the end of the seventh century, the Caliphate's policy toward Armenia and the Christian faith hardened. Special representatives of the Caliph called ostikans (governors) were sent to govern Armenia. The governors made the city of Dvin their residence. Although Armenia was declared the domain of the Caliph, almost all Armenians, although not all, remained faithful to Christianity. In the beginning of the eighth century, Arab tribes from the Hejaz and Fertile Crescent began migrating to and settling in major Armenian urban centers, such as Dvin, Diyarbekir, Manzikert, and Apahunik'.[7]

Medieval

editThe Muslim element in Armenia grew progressively stronger during the medieval period. Following the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert in 1071, waves of Turkic nomads making their way from Central Asia and northern Iran penetrated and eventually settled throughout the span of Armenia and Anatolia.[8][9]

Most Ethnic Armenians remained Christian during this period when Western Armenia was divided between Muslim states after the Seljuk invasion. Although some Armenians converted to Islam and became influential members of Beylik society, Armenian architecture influenced Seljuk architecture, and many Armenian Nakharars remained autonomous leaders of Armenian society under Muslim Emirs In Erzincan, Tayk, Sassoun, and Van. The Muslim Emirs intermarried with Armenians, Notably the Shaddadids of Ani who intermarried with Bagratid women. There was an Emir of Van named Ezdin who had Armenian sympathies and was said to be descended from Seneqerim Hovhannes Artsruni, the king of Vaspurakan. The son of Armenian prince Taharten, governor of Erzinjan, His son by a daughter of the emperor of Trebizond converted to Islam and was made governor of erzincan by Timur.[10]

Under the Ottoman Empire

editThe Ottoman Empire ruled in accordance to Islamic law. As such, the People of the Book (the Christians and the Jews) had to pay a tax to fulfill their status as dhimmi and in return were guaranteed religious autonomy. While the Armenians of Constantinople benefitted from the Sultan's support and grew to be a prospering community, the same could not be said about the ones inhabiting historic Armenia. During times of crisis the ones in the remote regions of mountainous often also had to suffer (alongside the settled Muslim population) raids by nomadic Kurdish tribes.[11] Armenians, like the other Ottoman Christians (though not to the same extent), had to transfer some of their healthy male children to the Sultan's government due to the devshirme policies in place.[12][13]

During the Ottoman period many Armenians were forced to convert to Islam throughout Western Armenia through massacres, social pressure, and harsh taxation. Many conversions were noted across eastern Anatolia, particularly in Hamshen, Yusufeli, Tortum, İspir, Bayburt, Erzincan. Notably a mass conversion to Islam was described by Armenian cleric Hakob (Yakob) Karnetsi. In the region of Tayk centered around Tortum, a Muslim cleric named Mullah Jaffar was given charge from the Ottoman government to take census of the Erzurum province and to levy taxes. After Mullah Jaffar placed excessively heavy taxes, the Chalcedonian Armenians who belonged to the Georgian Orthodox Church and made up half of the population in the Tortum valley converted to Islam while the Apostolic Armenians did not, as described by Karnetsi.[14]

In the region of İspir (Sper in Armenian), 100 Armenian villages were burned down in 1723 and much of the population was converted to Islam by force. In the region of Yusufeli (Pertakrak in Armenian), Armenian Catholic priest Inchichian writes that most of the Muslim population was Armenian in origin but had converted to Islam to escape heavy taxation and oppression in the early 1700s; Inchichian visited the village of Khewag (Yaylalar) and met Islamized Armenians in the village. The Armenians of Yusufeli were mostly Chalcedonian like the Armenians of Tortum before their islamization.[15] In the province of Urfa, there were three Islamized Armenian villages recorded to have been speaking a dialect that was similar to classical Armenian.[16] Inchichian also wrote that the region of Kemah in Erzincan used to be Armenian and that its Muslim inhabitants were also of Islamized Armenian descent.

In the early 1500s, the Ottomans brutally enforced taxation by massacring 10,000 Armenians in Bayburt, Erzincan, Ispir, Erzurum, and forcibly converted another 50,000 to Islam. In the region of Dersim, the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople reported that groups of Armenians had converted to Alevi Islam and had assimilated with Kurdish Zazas who had migrated to Armenia during Ottoman rule.[16] similarly in the region of Palu some Armenian villages converted to Sunni Islam and assimilated into the Sunni Zaza community.[17]

Periodic forced conversions created a class of crypto-Christian Armenians called Kes-kes (Half-half) who practiced both Christian and Muslim rituals. The Armenians who converted to Islam lost their Armenian identity because they switched millets, but many kept the Armenian language and culture. In eastern Anatolia, however, they were eventually Turkified except for the Armenians of Hamshen who kept their language in the isolated Pontic Mountains until Turkish Muslim schools were opened in the 1800s and the western Hemshin became Turkified as the Armenian language was condemned as sinful by Muslim teachers. In Turkey only the Hopa Hemshin have preserved their language, which constitutes the Homshetsi dialect of Armenian, in the modern era.[16]

During the Hamidian massacres when Kurdish tribes were incited by the Ottoman government to attack and destroy Armenian settlements many Armenian were forced to convert to Islam throughout eastern Anatolia. In Diyarbakir 20,000 were converted, while many also converted in Mush, Van, and Erzurum. Although some converted back to Christianity after the massacres ended, many remained Muslims and became Kurdified and Turkified. In the region of Sivas in the early 19th century many Armenian villages were forcefully converted to Islam by the local government. The village of Cancova (Cancik) in Zara was a village of 400 Armenian families in 1877, but only 48 families remained Christian by the 20th century. The Catholic Armenians of Perkinik has reported that their neighboring village of Glkhategh (now Uzuntepe) was an Armenian village and the Armenians were forcibly converted to Islam and Turkified.[18]

During the Armenian genocide of 1915, many Armenians converted to Islam to escape deportation and massacre.

Under Iranian Empires

editThe Iranian Safavids (who had changed from being Sunni to Shia Muslims by then), established definite control over Armenia and far beyond since the time of Shah Ismail I in the early 16th century. Even though they often competed with the Ottomans over the territory, what is today Armenia always stayed an integral part of Persian territory, during the following centuries until they had to cede it to Russia following the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828). Many Armenians joined the Safavid functions, in the civil administration and the military (the so-called ghulams) since the time of Shah Abbas the Great. Especially amongst these elite soldier units, the ghulams (literally meaning slaves), many of them were converted Armenians, alongside the masses of Circassians and Georgians. Before joining these functions, whether in the civil administration or military, they always had to convert to Islam, like in the Ottoman Empire, but the ones who stayed Christian (but couldn't get to the highest functions) did not have to pay extra taxes unlike the Ottoman Empire.

As a part of Abbas his scorched earth policy during his wars against the Ottomans, and also to boost his empire's economy, he alone deported some 300,000 Armenians from the Armenian highlands including the territory of modern-day Armenia, to the heartland of Iran.[19] To fill in the gap created in these regions, he settled masses of Muslim Turcomans and Kurds in the regions to defend the borders against the Ottoman Turks, making the area of Armenia a Muslim dominated one. His successors continued to do more of these deportations and replacements with Turcomans and Kurds. The Safavid suzerains also created the Erivan Khanate over the region, making it similar to a system as was made during the Achaemenid times were satraps would rule the area in place of the king letting the entire Armenian highland stay Muslim ruled, until the early 19th century.

By the time the Iranians had to cede their centuries long suzerainty over Armenia, the majority of the population in what is now Armenia were Muslims. (Persians, Azerbaijani's, Kurds and North Caucasians)

Due to the early Shi'ite zeal of the Safavids to convert all populations of Iran to Shia Islam, Many Armenians were heavily pressured to convert throughout Eastern Armenia. A law was passed by Islamic clerics declaring that any Armenian who converted to Islam would inherit his relative's belongings up to the 7th generation, because of this law many Armenians in Safavid Armenia began to convert to Islam.[20] The Catholic diocese of Nakhichevan reported that in the mid 1600s 130 Armenian families of the villages of Saltaq, Kirne had converted to Islam to avoid losing their belongings. The diocese pleaded with the Pope and the king of Spain to intercede with the Shah of Iran to lessen the persecution of Armenians. In the 1700s Catholic missionaries warned that if the forced conversions didn't stop, the entire Christian Armenian population would disappear from conversions and Turkification, writing that there were only a handful Armenians left in the village of Ganza in Ordubad province.

Tsarist period

editDuring the late Tsarist period Muslim populations made up substantial populations in the territory of present-day Armenia. In the Russian Imperial Census of 1897 Muslim populations made up 362,565 of a total population of 829,556 in the Erivan Governorate, which roughly corresponds to modern-day central Armenia, the Iğdır Province of Turkey, and the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan.[21] 41,417 Tatar Turks, 27,075 Armenians and 19,099 Kurds lived in the Surmalu uezd, part of Turkey today.[21] In the Sharur-Daralayaz uezd, today split across Armenia and Azerbaijan, 20,726 Armenians were likewise outnumbered by the Muslim population, consisting of 3,761 Kurds and 51,560 Tatars.[21] With the influx of Armenian refugees in the aftermath of the Armenian genocide, the demographic balance shifted in favor of Armenian populations.

First Republic of Armenia

editThe government of the First Republic of Armenia pursued a policy of ethnic homogenisation in favour of Armenians in the areas under its control. In 1917–1921, Muslims in Armenia were subject to largescale massacres and deportations orchestrated by Armenian partisans, leading to the destruction of dozens of Muslim settlements, killings of thousands of Muslim civilians and the displacement of as many as 235,000.[22][23]

The governance of Armenia was undermined by large-scale Muslim uprisings encouraged by Turkish and Azerbaijani agents, primarily in the Ararat, Kars, and Nakhichevan areas, in 1919–1920.[24][25]

Soviet period

editWith the historical provinces being subsumed within the borders of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the remainder of Armenia became a part of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. A small number of Muslims were resident in Armenia while it was a part of the Soviet Union, consisting mainly of Azeris and Kurds, the great majority of whom left in 1988 after the Sumgait Pogroms and the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, which caused the Armenian and Azeri communities of each country to have something of a population exchange, with Armenia getting around 500,000 Armenians previously living in Azerbaijan outside of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic,[26] and the Azeris getting around 724,000 people who were forced from Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh.[26]

Independent Armenia

editSince Armenia gained its independence in 1991, the majority of Muslims still living in the country are temporary residents from Iran and other countries. In 2009, the Pew Research Center estimated that 0.03%, or about 1,000 people, were Muslims – out of total population of 2,975,000 inhabitants.[27][28]

Population census conducted in 2011 counted 812 Muslims in Armenia,[29] the majority of which were from Iran.[30]

Cultural heritage

editA significant number of mosques were erected in historical Armenia between the Middle Ages and the Modern age[citation needed], though it was not unusual for Armenian and other Christian churches to be converted into mosques, as was the case, for example, of the Cathedral of Kars, Cathedral of Ani, and Holy Mother of God Church in Gaziantep.

The Blue Mosque of Yerevan is the only active mosque in Armenia today, having been restored and opened for religious services in cooperation between Armenian and Iranian authorities following the collapse of the Soviet Union.[31] In 2022, plans were announced in cooperation between Iranian authorities and the Yerevan municipality to renovate the Abbasqoli Khan Mosque (also known as the Thapha Bashi Mosque), an old mosque in ruins, located in the Kond quarter of Yerevan.[32]

The Qur'an

editThe first printed version of the Qur'an translated into the Armenian language from Arabic appeared in 1910. In 1912 a translation from a French version was published. Both were in the Western Armenian dialect. A new translation of the Qur'an in the Eastern Armenian dialect was started with the help of the embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran located in Yerevan. The translation was done by Edward Hakhverdyan from Persian in three years.[33] A group of Arabologists have been helping with the translation. Each of the 30 parts of Qur'an have been read and approved by the Tehran Center of Qur'anic Studies.[34] The publication of 1,000 copies of the translated work was done in 2007.

Notable Armenian Muslims

editSee also

editReferences

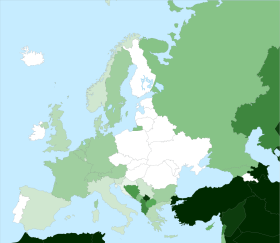

edit- ^ "Muslim Population Growth in Europe Pew Research Center". 2024-07-10. Archived from the original on 2024-07-10.

- ^ a b Ter-Ghewondyan, Aram (1976). The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. Trans. Nina G. Garsoïan. Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

- ^ Vryonis, Speros (1971). The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Historical dictionary of Sufism By John Renard, pg. 87

- ^ Kurkjian, Vahan M.A History of Armenia hosted by The University of Chicago. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America, 1958 pp. 173–185

- ^ On the Arab invasions, see also (in Armenian) Aram Ter-Ghewondyan (1996), Հայաստանը VI-VIII դարերում [Armenia in the 6th to 8th centuries]. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences.

- ^ Ter-Ghevondyan, Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia, pp. 29ff.

- ^ Cahen, Claude (1988). La Turquie pré-ottomane. Istanbul-Paris: Institut français d’études anatoliennes d’Istanbul.

- ^ Korobeinikov, Dimitri A. (2008). “Raiders and Neighbours: The Turks (1040–1304),” in The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire, c. 500‐1492, ed. Jonathan Shepard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 692–727.

- ^ "Armenia during the Seljuk and Mongol Periods".

- ^ McCarthy, Justin (1981). The Ottoman Peoples and the End of Empire. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 63.

- ^ Kouymjian, Dickran (1997). "Armenia from the Fall of the Cilician Kingdom (1375) to the Forced Migration under Shah Abbas (1604)" in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 12–14. ISBN 1-4039-6422-X.

- ^ (in Armenian) Zulalyan, Manvel. "«Դեվշիրմեն» (մանկահավաքը) օսմանյան կայսրության մեջ ըստ թուրքական և հայկական աղբյուրների" [The "Devshirme" (Child-Gathering) in the Ottoman Empire According to Turkish and Armenian Sources]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes. № 2–3 (5–6), 1959, pp. 247–256.

- ^ Simonian, Hovann (January 2007). "Hemshin from Islamicization to the End of the Nineteenth Century". The Hemshin, History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey. doi:10.4324/9780203641682. ISBN 9780203641682.

- ^ http://ysu.am/files/1-1512129568-.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c http://www.fundamentalarmenology.am/datas/pdfs/292.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Alevized Armenians in Dersim". Western Armenia TV. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ "Untitled".

- ^ Avedis Krikor Sanjian. Medieval Armenian Manuscripts at the University of California, Los Angeles University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0520097926 p 39

- ^ http://shsu.am/media/journal/2013n2b/7.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c Leupold, David (2020). Embattled Dreamlands. The Politics of Contesting Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish Memory. New York: Routledge. pp. 93–94.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1982). The Republic of Armenia: From Versailles to London, 1919–1920. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 147, 178, 213. ISBN 978-0520041868.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1996). The Republic of Armenia: From London to Sèvres, February–August 1920. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0520088030.

- ^ Bechhofer Roberts, Carl Eric (1921). In Denikin's Russia And The Caucasus, 1919–1920: Being A Record Of A Journey To South Russia, The Crimea, Armenia, Georgia, And Baku In 1919 And 1920. p. 263.

[On] the Igdir front … General Sebo [Sebouh] was holding the Kurds at bay. … [T]owards Ararat … was the Kamarloo [Artashat] front. There the enemy was the Tartar, supported, of course, by Turkish auxiliaries and excited by their agents. Far away in the East is the way to Nahichevan, which was in the possession of the enemy.

- ^ Somakian, Manough Joseph (1992). Tsarist and Bolshevik Policy Towards the Armenian Question 1912–1920 (PDF). London: University of London. p. 311. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2022.

By the summer of 1919, the question of repatriation was completely overshadowed by widespread Muslim uprisings. The issues at stake had transformed the repatriation question into a matter of Armenian survival.

- ^ a b "Gefährliche Töne im "Frozen War"." Wiener Zeitung. 2 January 2013.

- ^ Miller, Tracy, ed. (October 2009), Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population (PDF), Pew Research Center, p. 31, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-10-10, retrieved 2009-10-08

- ^ "2011 Census data" (PDF). p. 7.

- ^ Media, Ampop (2017-12-26). "Կրոնական կազմը Հայաստանում | Ampop.am". Ampop.am. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- ^ Karamyan, Sevak; Avetikyan, Gevorg (2022). "Armenia (Vol 13, 2020)". In Müssig, Stephanie; Račius, Egdunas; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Nielsen, Jørgen S.; Scharbrodt, Oliver (eds.). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Online. Brill Online.

- ^ "Armenian Premier Receives Iranian Delegation". Daily Report: Soviet Union (35–39). Foreign Broadcast Information Service: 103–104. 22 February 1991.

The guests had a businesslike meeting at Yerevan city soviet executive committee where an agreement was drafted to repair the capital's 17th century Persian architectural edifice, the Blue Mosque. In keeping with the agreement, Iran will send renovation specialists to Yerevan and will provide the necessary amount of construction material. Plans are to complete the renovation work before 1995.

- ^ "Iran ready to help restore Yerevan mosque". Tehran Times. 2022-09-13. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ The Qur'an is published in the Armenian language Archived 2007-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Qur'an in Armenian Archived 2007-02-10 at the Wayback Machine