The history of the United States from 1964 to 1980 includes the climax and end of the Civil Rights Movement; the escalation and ending of the Vietnam War; the drama of a generational revolt with its sexual freedoms and use of drugs; and the continuation of the Cold War, with its Space Race to put a man on the Moon. The economy was prosperous and expanding until the recession of 1969–70, then faltered under new foreign competition and the 1973 oil crisis. American society was polarized by the ultimately futile war and by antiwar and antidraft protests, as well as by the shocking Watergate affair, which revealed corruption and gross misconduct at the highest level of government. By 1980 and the seizure of the American Embassy in Iran, including a failed rescue attempt by U.S. armed forces, there was a growing sense of national malaise.

| The United States of America | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964–1980 | |||

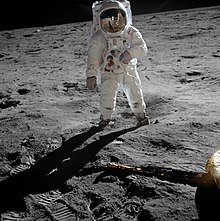

Buzz Aldrin in 1969 as part of NASA's Apollo 11 spaceflight that was the first to land humans on the Moon | |||

| Location | United States | ||

| Including | Late New Deal Era Cold War Fourth Great Awakening Second Great Migration Third Industrial Revolution | ||

| President(s) | Lyndon B. Johnson Richard Nixon Gerald Ford Jimmy Carter | ||

| Key events | Civil Rights Movement Space Race Vietnam War Détente 60s Counterculture Assassination of Malcolm X Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy 1970s energy crisis Watergate Scandal Iran Hostage Crisis Neoconservative movement Moral Majority movement | ||

Chronology

| |||

The period closed with the victory of conservative Republican Ronald Reagan, opening the "Age of Reagan" with a dramatic change in national direction.[1] The Democratic Party split over the Vietnam War and other foreign policy issues, with a new strong dovish element based on younger voters. Many otherwise liberal Democratic "hawks" joined the Neoconservative movement and started supporting the Republicans—especially Reagan—based on foreign policy.[2] Meanwhile, Republicans were generally united on a hawkish and intense American nationalism, strong opposition to Communism, support for promoting democracy and human rights, and strong support for Israel.[3]

Memories of the mid-late 1960s and early 1970s shaped the political landscape for the next half-century. As President Bill Clinton explained in 2004, "If you look back on the Sixties and think there was more good than bad, you're probably a Democrat. If you think there was more harm than good, you're probably a Republican."[4]

Johnson administration

editClimax of liberalism

editThe climax of liberalism came in the mid-1960s with the success of President Lyndon B. Johnson (1963–69) in securing congressional passage of his Great Society programs, including civil rights, the end of segregation, Medicare, extension of welfare, federal aid to education at all levels, subsidies for the arts and humanities, environmental activism, and a series of programs designed to wipe out poverty.[5][6] As a 2005 American history textbook explains:[7]

- Gradually, liberal intellectuals crafted a new vision for achieving economic and social justice. The liberalism of the early 1960s contained no hint of radicalism, little disposition to revive new deal era crusades against concentrated economic power, and no intention to redistribute wealth or restructure existing institutions. Internationally it was strongly anti-Communist. It aimed to defend the free world, to encourage economic growth at home, and to ensure that the resulting plenty was fairly distributed. Their agenda—much influenced by Keynesian economic theory—envisioned massive public expenditure that would speed economic growth, thus providing the public resources to fund larger welfare, housing, health, and educational programs. Johnson was sure this would work.

Johnson was rewarded with an electoral landslide in 1964 against conservative Barry Goldwater, which broke the decades-long control of Congress by the conservative coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats. However, the Republicans bounced back in 1966, and Republican Richard Nixon won the presidential election in 1968. Nixon largely continued the New Deal and Great Society programs he inherited; a more conservative reaction would come with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.[8]

Cultural "Sixties"

editThe term "The Sixties" covers inter-related cultural and political trends around the globe. This "cultural decade" began around 1963 with the Kennedy assassination and ending around 1974 with the Watergate scandal.[9][10]

Shift to the extremes in politics

editThe common thread was a growing distrust of government to do the right thing on behalf of the people. While general distrust of high officials had been an American characteristic for two centuries, the Watergate scandal of 1973–1974 forced the resignation of President Richard Nixon, who faced impeachment, as well as criminal trials for many of his senior associates. The media was energized in its vigorous search for scandals, which deeply impacted both major parties at the national, state, and local levels.[11] At the same time there was a growing distrust of long-powerful institutions such as big business and labor unions. The postwar consensus regarding the value of technology in solving national problems came under attack, especially nuclear power, came under heavy attack from the New Left.[12]

Conservatives at the state and local levels increasingly emphasized the argument that the soaring crime rates indicated a failure of liberal policy in the American cities.[13]

Meanwhile, liberalism was facing divisive issues, as the New Left challenged established liberals on such issues as the Vietnam War, and built a constituency on campuses and among younger voters. A "cultural war" was emerging as a triangular battle among conservatives, liberals, and the New Left, involving such issues as individual freedom, divorce, sexuality, and even topics such as hair length and musical taste.[14]

An unexpected new factor was the emergence of the religious right as a cohesive political force that gave strong support to conservatism.[15][16]

The triumphal issue for liberalism was the achievement of civil rights legislation in the 1960s, which won over the black population created a new black electorate in the South. However, it alienated many working-class ethnic whites, and opened the door for conservative white Southerners to move into the Republican Party.[17]

In foreign policy, the war in Vietnam was a highly divisive issue in the 1970s. Nixon had introduced a policy of detente in the Cold War, but it was strongly challenged by Reagan and the conservative movement. Reagan saw the Soviet Union as an implacable enemy that had to be defeated, not compromised with. A new element emerged in Iran, with the overthrow of a pro-American government, and the emergence of the stream of hostile ayatollahs. Radical students seized the American Embassy, and held American diplomats hostage for over a year, underscoring the weaknesses of the foreign policy of Jimmy Carter.[18]

The economic scene was in doldrums, with soaring inflation undercutting the savings pattern of millions of Americans, while unemployment remained high and growth was low. Shortages of gasoline and the local pump made the energy crisis a local reality.[19]

Ronald Reagan in 1964–1968 emerged as the leader of a dramatic conservative shift in American politics, that undercut many of the domestic and foreign policies that had dominated the national agenda for decades.[20][21]

Civil Rights Movement

editThe 1960s were marked by street protests, demonstrations, rioting, civil unrest,[22] antiwar protests, and a cultural revolution.[23] African American youth protested following victories in the courts regarding civil rights with street protests led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel, and the NAACP.[24] King and Bevel skillfully used the media to record instances of brutality against non-violent African American protesters to tug at the conscience of the public. Activism brought about successful political change when there was an aggrieved group, such as African Americans or feminists or homosexuals, who felt the sting of bad policy over time, and who conducted long-range campaigns of protest together with media campaigns to change public opinion along with campaigns in the courts to change policy.[25]

The assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 helped change the political mood of the country. The new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, capitalized on this situation, using a combination of the national mood and his own political savvy to push Kennedy's agenda; most notably, the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In addition, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 had an immediate impact on federal, state and local elections. Within months of its passage on August 6, 1965, one quarter of a million new black voters had been registered, one third by federal examiners. Within four years, voter registration in the South had more than doubled. In 1965, Mississippi had the highest black voter turnout, 74%, and had more elected black-leaders than any other state. In 1969, Tennessee had a 92.1% voter turnout, Arkansas 77.9%, and Texas 77.3%.[26]

Election of 1964

editIn the election of 1964, Lyndon Johnson positioned himself as a moderate, contrasting himself against his GOP opponent, Barry Goldwater, who the campaign characterized as solidly conservative. Most famously, the Johnson campaign ran a commercial entitled the "Daisy Girl" ad, which featured a little girl picking petals from a daisy in a field, counting the petals, which then segues into a launch countdown and a nuclear explosion. Johnson soundly defeated Goldwater in the general election, winning 61.1% of the popular vote, and losing only five states in the Deep South, where blacks were not yet allowed to vote, along with Goldwater's Arizona.

Goldwater's race energized the conservative movement, chiefly inside the Republican party. It looked for a new leader and found one in Ronald Reagan, elected governor of California in 1966 and reelected in 1970. He ran against President Ford for the 1976 GOP nomination, and narrowly lost, but the stage was set for Reagan in 1980.[27]

Anti-poverty programs

editTwo main goals of the Great Society social reforms were the elimination of poverty and racial injustice. New major spending programs that addressed education, medical care, urban problems, and transportation were launched during this period. The Great Society in scope and sweep resembled the New Deal domestic agenda of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s, but differed sharply in types of programs enacted. The largest and most enduring federal assistance programs, launched in 1965, were Medicare, which pays for many of the medical costs of the elderly, and Medicaid, which aids the impoverished.[28]

The centerpiece of the War on Poverty was the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which created an Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) to oversee a variety of community-based antipoverty programs. The OEO reflected a fragile consensus among policymakers that the best way to deal with poverty was not simply to raise the incomes of the poor but to help them better themselves through education, job training, and community development. Central to its mission was the idea of "community action", the participation of the poor in framing and administering the programs designed to help them.[29]

Generational revolt and counterculture

editAs the 1960s progressed, increasing numbers of young people began to revolt against the social norms and conservatism from the 1950s and early 1960s as well as the escalation of the Vietnam War and Cold War. A social revolution swept through the country to create a more liberated society. As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, feminism and environmentalism movements soon grew in the midst of a sexual revolution with its distinctive protest forms, from long hair to rock music. The hippie culture, which emphasized peace, love and freedom, was introduced to the mainstream. In 1967, the Summer of Love, an event in San Francisco where thousands of young people loosely and freely united for a new social experience, helped introduce much of the world to the culture. In addition, the increased use of psychedelic drugs, such as LSD and marijuana, also became central to the movement. Music of the time also played a large role with the introduction of folk rock and later acid rock and psychedelia which became the voice of the generation. The Counterculture Revolution was exemplified in 1969 with the historic Woodstock Festival.[30] After experiencing declining homicide rates during the Great Depression, World War II, and during the initial Cold War, the U.S. homicide rate increased by a factor of 2.5 between 1957 and 1980 while rates of rape, assault, robbery, and theft experienced similar surges and did not return to comparable levels until the 1990s.[31][32]

Conclusion of the Space Race

editBeginning with the Soviet launch of the first satellite, Sputnik 1, in 1957, the United States competed with the Soviet Union for supremacy in outer space exploration. After the Soviets placed the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, in 1961, President John F. Kennedy pushed for ways in which NASA could catch up,[33] famously urging action for a crewed mission to the Moon: "I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth."[34] The first crewed flights produced by this effort came from Project Gemini (1965–1966) and then by the Apollo program, which despite the tragic loss of the Apollo 1 crew, achieved Kennedy's goal by landing the first astronauts on the Moon with the Apollo 11 mission in 1969.

Having lost the race to the Moon, the Soviets shifted their attention to orbital space stations, launching the first (Salyut 1) in 1971. The U.S. responded with the Skylab orbital workstation, in use from 1973 through 1974. With détente, a time of relatively improved Cold War relations between the United States and the Soviets, the two superpowers developed a cooperative space mission: the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project. This 1975 joint mission was the last crewed space flight for the U.S. until the Space Shuttle flights of 1981 and has been described as the symbolic end of the Space Race. The Space Race sparked unprecedented increases in spending on education and pure research, which accelerated scientific advancements and led to beneficial spin-off technologies.[citation needed]

Vietnam War

editThe Containment policy meant fighting communist expansion where ever it occurred, and the Communists aimed where the American allies were weakest. Johnson's primary commitment was to his domestic policy, so he tried to minimize public awareness and congressional oversight of the operations in the war.[35] Most of his advisers were pessimistic about the long term possibilities, and Johnson feared that if Congress took control, it would demand "Why Not Victory", as Barry Goldwater put it, rather than containment.[36] Although American involvement steadily increased, Johnson refused to allow the reserves or the National Guard to serve in Vietnam, because that would involve congressional oversight. In August 1964 Johnson secured almost unanimous support in Congress for the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave the president very broad discretion to use military force as he saw fit. In July 1965, after extensive consultation and no publicity Johnson dramatically escalated the war, sending in American combat troops to fight the Viet Cong on the ground, and mobilizing the U.S. Air Force to bomb its supply lines. By 1968 a half million American soldiers and Marines were in South Vietnam, while additional Air Force units were stationed in Thailand and other bases. In February 1968 the Viet Cong launched an all-out attack on South Vietnamese forces across the country in the Tet Offensive. The ARVN (South Vietnam's army) successfully fought off the attacks and reduced the Viet Cong to a state of ineffectiveness; thereafter, it was the army of North Vietnam that was the main opponent.[37] However the Tet Offensive proved a public relations disaster for Johnson, as the public increasingly realized the United States was deeply involved in a war that few people understood. Republicans, such as California Governor Ronald Reagan, demanded victory or withdrawal, while on the left strident demands for immediate withdrawal escalated.[38] Controversially, out of the 2.5 million Americans who came to serve in Vietnam (out of 27 million Americans eligible to serve in the military) 80% came from poor and working-class backgrounds.[39]

Antiwar movement

editStarting in 1964, the antiwar movement began. Some opposed the war on moral grounds, rooting for the peasant Vietnamese against the modernizing capitalistic Americans. Opposition was centered among the black activists of the civil rights movement, and college students at elite universities.[40]

The Vietnam War was unprecedented for the intensity of media coverage—it has been called the first television war—as well as for the stridency of opposition to the war by the "New Left".[citation needed]

Despite their high media profile, antiwar activists never represented more than a relative minority of the American population, and most tended to be college educated and from higher than average income brackets. Polls showed that most Americans favored carrying out the war to a victorious conclusion, although conversely, few were willing to carry out mass mobilization and expansion of the draft in the pursuit of victory. Even Republican candidates in the 1968 presidential election, including Nixon and California governor Ronald Reagan, did not call for total war and the use of nuclear weapons on North Vietnam, believing that Barry Goldwater's hawkish stance may have cost him his bid for the White House four years earlier.

The Vietnam draft did have numerous flaws in it, especially its high reliance on lower middle class Americans while exempting college students, celebrities, athletes, and sons of Congressmen, although contrary to the claims of antiwar activists, most draftees were not impoverished white and black youths who had no other job opportunity. The average Vietnam draftee was white and from a lower middle class, blue collar background. Only a tiny handful of Ivy League graduates numbered among the 58,000 US servicemen killed or wounded in the eight years between 1965 and 1973.

The Vietnam draft in fact took fewer men than the Korean War draft and the conflict on the whole caused little disruption to most Americans' lives. Although a sizable portion of US manufacturing was tied up in supporting the war effort, imports of low-cost goods from Asian countries made up for the shortfall and there was no rationing or cutbacks of consumer goods as had occurred in the previous conflicts of the 20th century. The US economy during the late 1960s indeed was booming, with unemployment under 5% and real GDP growth averaging 6% a year.

1968 and the divorce of the Democratic Party

editIn 1968, Johnson saw his overwhelming coalition of 1964 disintegrate. Liberal and moderate Republicans returned to their party, and supported Richard Nixon for the GOP nomination. George Wallace pulled off the majority of Southern whites, for a century the core of the Solid South in the Democratic Party. Increasingly, the blacks, students, and intellectuals were fiercely opposed to Johnson's policy. With Robert Kennedy hesitant about joining the contest, Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy, jumped in on an antiwar platform, building a coalition of intellectuals and college students. McCarthy was not nationally known, but came close to Johnson in the critical primary in New Hampshire, thanks to thousands of students who took off their counter-culture garb and went "clean for Gene" to campaign for him door-to-door. Johnson no longer commanded majority support in his party, so he took the initiative and dropped out of the race, promising to begin peace talks with the enemy.[41]

Seizing the opportunity caused by Johnson's departure from the race, Robert Kennedy then joined in and ran for the nomination on an antiwar platform that drew support from ethnics and blacks. Vice President Hubert Humphrey was too late to enter the primaries, but he did assemble strong support from traditional factions in the Democratic Party. Humphrey, an ardent New Dealer, supported Johnson's war policy. The greatest outburst of rioting in national history came in April 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.[citation needed]

Kennedy was on stage to claim victory over McCarthy in the California primary when he was assassinated; McCarthy was unable to overcome Humphrey's support within the party elite. The Democratic national convention in Chicago was in a continuous uproar, with police confronting antiwar demonstrators in the streets and parks, and the bitter divisions of the Democratic Party revealing themselves inside the arena. Humphrey, with a coalition of state organizations, city bosses such as Mayor Richard Daley, and labor unions, won the nomination and ran against Republican Richard Nixon and independent George Wallace in the general election. Nixon appealed to what he claimed was the "silent majority" of moderate Americans who disliked the "hippie" counterculture. Nixon also promised "peace with honor" in ending the Vietnam War. He proposed the Nixon Doctrine to establish the strategy to turn over the fighting of the war to the Vietnamese, which he called "Vietnamization." Nixon won the presidency, but the Democrats continued to control Congress. The profound splits in the Democratic Party lasted for decades.[42]

Transformation of gender relations

editThe Women's Movement (1963–1982)

editA new consciousness of the inequality of American women began sweeping the nation, starting with the 1963 publication of Betty Friedan's best-seller, The Feminine Mystique, which explained how many housewives felt trapped and unfulfilled, assaulted American culture for its creation of the notion that women could only find fulfillment through their roles as wives, mothers, and keepers of the home, and argued that women were just as able as men to do every type of job. In 1966, Friedan and others established the National Organization for Women, or NOW, to act as an NAACP for women.[43][44]

Protests began, and the new "Women's Liberation Movement" grew in size and power, gained much media attention, and, by 1968, had replaced the Civil Rights Movement as the U.S.'s main social revolution.[citation needed] Marches, parades, rallies, boycotts, and pickets brought out thousands, sometimes millions; Friedan's Women's Strike for Equality (1970) was a nationwide success. The movement was split into factions by political ideology early on, however (NOW on the left, the Women's Equity Action League (WEAL) on the right, the National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC) in the center, and more radical groups formed by younger women on the far left).[citation needed]

Along with Friedan, Gloria Steinem was an important feminist leader, co-founding the NWPC, the Women's Action Alliance, and editing the movement's magazine, Ms. The proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in 1972 and favored by about seventy percent of the American public, failed to be ratified in 1982, with only three more states needed to make it law. The nation's conservative women, led by activist Phyllis Schlafly, defeated the ERA by arguing that it degraded the position of the housewife, and made young women susceptible to the military draft.[45][46] There was also a disconnect between the older, relatively conservative Betty Friedan and the younger feminists, many of whom favored left-wing politics and radical ideas such as forced redistribution of jobs and income from men to women. Friedan's primary interest was also in workplace and income inequality, and she was largely unmoved by the abortion and sexual rights activists, feeling in particular that abortion was an unimportant issue. In addition, the feminist movement remained dominated by relatively affluent white women. It failed to attract many African-American females, who tended to be of the opinion that they were victims of their race rather than their gender and that many of the feminists came from comfortable middle-class backgrounds who had seldom experienced serious hardship in their lives. The women's liberation movement can be said to have effectively ended with the failure of the ERA in 1982 along with the more conservative climate of the Reagan years.

The failure of the ERA notwithstanding, many federal laws (e.g. those equalizing pay, employment, education, employment opportunities, credit, ending pregnancy discrimination, and requiring NASA, the Military Academies, and other organizations to admit women), state laws (i.e. those ending spousal abuse and marital rape), Supreme Court rulings (i.e. ruling the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applied to women), and state ERAs established women's equal status under the law, and social custom and consciousness began to change, accepting women's equality.[citation needed]

Abortion

editAbortion became a highly controversial issue with the Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade in 1973 that women have a constitutional right to choose an abortion, and that cannot be nullified by state laws. Feminists celebrated the decisions but Catholics, who had opposed abortion since the 1890s, formed a coalition with Evangelical Protestants to try to reverse the decision. The Republican party began taking anti-abortion positions as the Democrats announced in favor of choice (that is, allowing women the right to choose an abortion). The issue has been a contentious one ever since.[47]

After 1973, over one million abortions were performed annually for the next decade; by 1977, abortion was a more common medical procedure in the US than tonsillectomies.[48][49]

The Sexual Revolution

editThe counterculture movement had rapidly dismantled many existing social taboos, and there was a growing acceptance of extramarital sex, divorce, and homosexuality. Some people advocated dropping all laws against sex between consenting adults, including prostitution, and LGBT people began the struggle for gay liberation.

A series of court rulings in the 1960s had struck down most anti-pornography laws, and under pressure from homosexual activist groups, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders in 1973. In 1967, the Hays Code, a censorship guideline imposed on the motion picture industry since the 1930s, was lifted and replaced by a new film content rating system, and by the 1970s, there was a surge in sexually-explicit movies and social commentary coming from Hollywood.

Notable X-rated films that were widely screened in the early 1970s (provoking much public controversy, and in some states, legal prosecution) include Deep Throat, The Devil in Miss Jones, and Last Tango in Paris, starring Marlon Brando, whose performance was nominated for an Academy Award. A new wave of raunchier adult magazines such as Hustler and Penthouse arrived, making Playboy seem dull and old-fashioned.

Due in large part to the dramatic reduction in the risk of unwanted pregnancy engendered by the introduction of the Pill in 1960, not to mention the legalization of contraception nationwide by the Supreme Court decision in Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965, along with the steadily increasing acceptance of abortion and delayed marriages for career-minded young women influenced by second-wave feminism, or the chic rejection of the responsibilities of marriage altogether in favor of living together without raising a family, U.S. birthrates fell below replacement level starting in 1965 and remained depressed for almost 20 years; thus, children born during this period became known, at least in the popular press, as "baby busters" (as opposed to the "baby boomers" of the postwar years). Birthrates hit an all-time low during the post-OPEC recession in the mid-1970s.

As the decade drew to a close, however, there was a growing disgust among many conservative Americans over the excesses of the sexual revolution and liberalism, which would culminate in a revival of conservatism during the next decade, and a backlash against the incipient gay rights movement.[citation needed]

Nixon administration

editAlthough generally regarded as a conservative, President Richard Nixon adopted many liberal positions, especially regarding health care, welfare spending, environmentalism and support for the arts and humanities. He maintained the high taxes and strong economic regulations of the New Deal era and he intervened aggressively in the economy. In August 1971, he took the nation off the gold standard of the Bretton Woods system and imposed (for a while) price and wage controls (Nixon Shock). During his final year in office, Nixon also proposed a national health care system.[50]

Nixon reoriented US foreign policy away from containment and toward detente with both the Soviet Union and China, playing them against each other (→ Cold War#From confrontation to détente (1962–1979)). Nixon promoted "Vietnamization," whereby the military of South Vietnam would be greatly enhanced so that U.S. forces could withdraw. The combat troops were gone by 1971 and Nixon could announce a peace treaty (Paris Peace Accords) in January 1973. His promises to Saigon that he would intervene if North Vietnam attacked were validated in 1972, but became worthless when he resigned in August 1974.

In May 1970, the antiwar effort escalated into violence, as National Guard troops shot at student demonstrators in the Kent State shootings. The nation's higher education system, especially the elite schools, virtually shut down.

In 1972, Nixon announced the end of mandatory military service which had been in effect since the Korean War, and the final American citizen to be conscripted received his draft notice in June 1973. The president also secured the passage of the 26th Amendment, lowering the minimum age of voting from 21 to 18.

The Nixon Administration seized on student demonstrations to mobilize a conservative majority consisting of middle-class suburbanites and working-class whites critical of radical extremists. Economics also played a role in this mobilization. As a result of the Vietnam War, and Lyndon Johnson's failure to raise taxes to pay for it, inflation shot up and real incomes declined. Many lower middle-class whites were critical of federal programs targeted towards blacks and the poor, with one observer noting that their wages were often only “a notch or so above the welfare payments of liberal states,” and yet “they are excluded from social programs targeted at the disadvantaged.”[51] Numerous articles published at that time focused on the feelings of discontent that existed amongst many Americans.[52][53][54][55][56]

Although middle-income Americans benefited from Great Society initiatives that also benefited low-income Americans, such as Medicare and federal aid to education,[57] and despite the fact that statistics indicated that blacks and the poor (with the two groups often treated as one) lived an immeasurably more painful existence than lower middle-class whites, there existed a widespread feeling that slum residents and ghetto residents were now in the driver's seat. A poll taken by Newsweek in 1969 found that a plurality of middle Americans believed that blacks had a better chance of getting adequate schooling, a decent home, and a good job. In that same poll, 85% believed that black militants were let off too easily, 84% that campus demonstrators were treated too leniently, and 79% that most people receiving welfare could help themselves. Analysts traced sentiments such as these to the economic insecurity of those dubbed the “middle Americans”, those earning between $5,000 and $15,000 a year and including many white ethnics, who were 55% of the American population. Most of these middle Americans were blue-collar workers, white-collar employees, school teachers, and lower-echelon bureaucrats. Although not poor, according to William H. Chafe they suffered from many of the tensions of marginal prosperity, such as indebtedness, inflation, and the fear of losing what they had worked so hard to attain. From 1956 to 1966, income had increased by 86%, while the cost of borrowing had gone up even more, by 113.% Many families were hard pressed to hold on to their “middle-class” status, particularly at a time when rising inflation brought an end to increases in real income. Struggling to get by, many middle Americans viewed antipoverty expenditures and black demands as representing a threat to their own well-being.[51]

Irregular employment was also a problem, with 20% of workers in 1969 unemployed for some period of time, a figure that rose to 23% in 1970.[58] Many people also had little or no savings by the end of the Sixties, with a fifth of the population in 1969 having no liquid assets, and nearly half the population having less than $500.[59]

By the end of 1967, as noted by William H. Chafe,

‘the shrill attacks on “establishment” values from the left were matched by an equally vociferous defense of traditional values by those who were proud of all their society had achieved. If feminists, blacks, antiwar demonstrators, and advocates for the poor attacked the status quo with uncompromising vehemence, millions of other Americans rallied around the flag and made clear their intent to uphold the lifestyle and values to which they had devoted their lives. Significantly, pollsters Richard Scammon and Ben Watterburg pointed out, the protesters still represented only a small minority of the country. The great majority of Americans were “unyoung, unpoor, and unblack; they [are] middle-aged, middle class, and middle minded.” It was not a scenario from which dissidents could take much comfort.’[51]

Riding on high approval ratings, Nixon was re-elected in 1972, defeating the liberal, anti-war George McGovern in a landslide with all states except Massachusetts. At the same time, Nixon became a lightning rod for much public hostility regarding the war in Vietnam. The morality of conflict continued to be an issue, and incidents such as the My Lai Massacre further eroded support for the war and increased efforts of Vietnamization.[citation needed]

The growing Watergate scandal was a major disaster for Nixon, eroding his political support in public opinion and in Washington. However he did manage to secure large-scale funding for South Vietnam, much of which was wasted. The United States withdrew its troops from Vietnam before the Paris Peace Accords in 1973. However, Watergate resulted in significant Democrat gains in the 1974 midterm elections and when the new 94th Congress convened the following January, it immediately voted to terminate all aid to South Vietnam in addition to passing a bill forbidding all further US military intervention in Southeast Asia. President Ford was against this, but as Congress had a veto-proof majority, he was forced to accept. South Vietnam rapidly collapsed as the North invaded it in force, and Saigon fell to the NVA on April 30, 1975. Later nearly one million Vietnamese managed to flee to the U.S. as refugees. The impact on the U.S. was muted, with few political recriminations, but it did leave a "Vietnam Syndrome" that cautioned against further military interventions anywhere else. Nixon (and his next two successors Ford and Carter) had dropped the containment policy and were not willing to intervene anywhere.[60]

"Stagflation"

editAt the same time that President Johnson persuaded Congress to accept a tax cut in 1964, he was rapidly increasing spending for both domestic programs and for the war in Vietnam. The result was a major expansion of the money supply, resting largely on government deficits, which pushed prices rapidly upward. However, inflation also rested on the nation's steadily declining supremacy in international trade and, moreover, the decline in the global economic, geopolitical, commercial, technological, and cultural preponderance of the United States since the end of World War II. After 1945, the U.S. enjoyed easy access to raw materials and substantial markets for its goods abroad; the U.S. was responsible for around a third of the world's industrial output because of the devastation of postwar Europe. By the 1960s, not only were the industrialized nations now competing for increasingly scarce raw commodities, but Third World suppliers were increasingly demanding higher prices. The automobile, steel, and electronics industries were also beginning to face stiff competition in the U.S. domestic market by foreign producers who had more modern factories and higher-quality products.[61]

Inflation had been an extremely gentle 3% a year from 1949 to 1969, but as the 70s unfolded, this began to change and the cost of energy and consumer products began to steadily climb. In addition to the increased manufacturing competition from Europe and Japan, the US faced other difficulties due to the general complacency that set in during the years of prosperity. Many Americans assumed the good times would last forever and there was little attempt at investing in infrastructure and modernized manufacturing outside of the defense and aerospace sectors. The boundless optimism and belief in science and progress that characterized the 1950s–60s quickly eroded and gave way to a general cynicism and distrust of technology among Americans, fueled by growing concern over the negative effects on the environment by air and water pollution from automobiles and manufacturing, especially events such as the Cuyahoga River Fire in Cleveland, Ohio in 1969 and the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in 1979.[62] Nixon promised to tackle sluggish growth and inflation, known as "stagflation", through higher taxes and lower spending; this met stiff resistance in Congress. As a result, Nixon changed course and opted to control the currency; his appointees to the Federal Reserve sought a contraction of the money supply through higher interest rates but to little avail; the tight money policy did little to curb inflation. The cost of living rose a cumulative 15% during Nixon's first two years in office.[citation needed]

Nixon's primary interests as president were in the world of diplomacy and foreign policy; by his own admission, domestic affairs bored him. His first Secretary of the Treasury, David M. Kennedy, was a soft-spoken Mormon businessman whom the president paid little attention to. In January 1971, Kennedy stepped down from office and was replaced by Texas governor and Lyndon Johnson confidante John Connally. By the summer of 1971, Nixon was under strong public pressure to act decisively to reverse the economic tide. On August 15, 1971, he ended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold, which meant the demise of the Bretton Woods system, in place since World War II. As a result, the U.S. dollar fell in world markets. The devaluation helped stimulate American exports, but it also made the purchase of vital inputs, raw materials, and finished goods from abroad more expensive. Nixon was reluctant to perform this step as he became convinced that moving entirely to fiat currency would give the Soviet Union the idea that capitalism was crumbling. Also, on August 15, 1971, under the provisions of the Economic Stabilization Act of 1970, Nixon implemented "Phase I" of his economic plan: a ninety-day freeze on all wages and prices above their existing levels. In November, "Phase II" entailed mandatory guidelines for wage and price increases to be issued by a federal agency. Inflation subsided temporarily, but the recession continued with rising unemployment. To combat the recession, Nixon reversed course and adopted an expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. In "Phase III", the strict wage and price controls were lifted. As a result, inflation resumed its upward spiral. The administration largely remained aloof; practically all press conferences and public statements by the White House dealt with foreign policy issues despite Gallup polls showing that the state of the economy was of concern to 80% of Americans. Connally stepped down as Treasury Secretary in 1973 and Secretary of Labor George Shultz took over the post.[63]

The administration's continued preoccupation with foreign policy matters stood in stark contrast to Gallup polls showing that the economy and cost of living was the primary concern for most Americans. Virtually all White House press conferences in 1973 dealt with Vietnam, superpower relations, and Watergate while almost totally ignoring economic issues that had a far more immediate impact on Americans' lives.

Inflationary pressures led to key shifts in economic policies. Following the Great Depression of the 1930s, recessions—periods of slow economic growth and high unemployment—were viewed as the greatest of economic threats, which could be counteracted by heavy government spending or cutting taxes so that consumers would spend more. In the 1970s, major price increases, particularly for energy, created a strong fear of inflation; as a result, government leaders concentrated more on controlling inflation than on combating recession by limiting spending, resisting tax cuts, and reining in growth in the money supply. Increases in the price of meat provoked public outcry and cumulated in the 1973 meat boycott. The erratic economic programs of the Nixon administration were indicative of a broader national confusion about the prospects for future American prosperity. Nixon and his advisers had a poor understanding of the complexities of the global economy (Henry Kissinger once confessed that economics were mostly a blank spot to him) and all of them belonged to the generation that came of age during the New Deal era and believed strongly in government intervention in the economy. They preferred quick, dirty, short-term fixes to complex economy issues. These underlying problems set the stage for conservative reaction, a more aggressive foreign policy, and a retreat from welfare-based solutions for minorities and the poor that would characterize the subsequent decades.[64]

Crime, riots and decay of the inner cities

editThe urban crisis of the 1960s continued to escalate in the 1970s, with major episodes of riots in many cities every summer. The postwar suburbanization boom had left America's inner cities neglected, as middle-class whites gradually moved out. Rundown housing was increasingly filled by an underclass, with high unemployment rates and high crime rates. Drugs became the most lucrative industry in the inner-city, with well-funded, well armed gangs fighting it out for control of their market. While the major decline in manufacturing came later, some industries declined sharply, such as textiles in New England. After the turmoil of the late 1960s and the advent of the Great Society, the urban inner cities began to sharply deteriorate. Nationwide crime rates, which had been low during the period leading up to 1965, suddenly started going up in 1967 and would remain so for the next quarter-century, a vexing social problem that plagued American society. "Law and Order" became a conservative campaign theme, using the argument that liberalism had subsidized unrest and failed to cure it.[65]

Although urban decay affected all major cities, New York City was hit especially hard by the loss of its traditional industries, in particular garment manufacturing. The city, which had once been the cultural, business, and industrial center of the nation, declined during the 1970s into a dystopian condition. Violent crime and drugs became a seemingly insurmountable problem in New York. Times Square became a Mecca for adult businesses, prostitutes, pimps, muggers, and rapists, and the subway system was in disrepair and dangerous to ride in. With the city facing bankruptcy in 1975, Mayor Abraham Beame requested a Federal bailout, but President Ford declined. In July 1977, a power blackout caused a rash of looting and destruction in mostly African-American and Hispanic neighborhoods. That year, Edward Koch was elected mayor with the promise of turning New York around; a process that gradually succeeded over the next 15 years.[66]

1973 oil crisis

editTo make matters worse, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) began displaying its strength; oil, fueling automobiles and homes in a country increasingly dominated by suburbs (where large homes and automobile-ownership are more common), became an economic and political tool for Third World nations to begin fighting for their concerns. Following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Arab members of OPEC announced they would no longer ship petroleum to nations supporting Israel, that is, to the United States and Western Europe. At the same time, other OPEC nations agreed to raise their prices 400%. This resulted in the 1973 world oil shock, during which U.S. motorists faced long lines at gas stations. Public and private facilities closed down to save on heating oil; and factories cut production and laid off workers. No single factor did more than the oil embargo to produce the soaring inflation of the 1970s, though this event was part of a much larger energy crisis that characterized the decade.[67]

The U.S. government response to the embargo was quick but of limited effectiveness. A national maximum speed limit of 55 mph (88 km/h) was imposed to help reduce consumption. President Nixon named William E. Simon as "Energy Czar", and in 1977, a cabinet-level Department of Energy was created, leading to the creation of the United States' Strategic Petroleum Reserve, not a new idea since the government in the 1970s still had a storage facility in the Midwest containing several million pounds of helium, a relic from the 1920s when military strategists envisioned airships as a major weapon of war. The National Energy Act of 1978 was also a response to this crisis. Rationing of gasoline became unpopular.[68]

The U.S. "Big Three" automakers' first order of business after Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards were enacted was to downsize existing automobile categories. By the end of the 1970s, huge 121-inch wheelbase vehicles with a 4,500 pound GVW (gross weight) were a thing of the past. Before the mass production of automatic overdrive transmissions and electronic fuel injection, the traditional front engine/rear wheel drive layout was being phased out for the more efficient and/or integrated front engine/front wheel drive, starting with compact cars. Using the Volkswagen Rabbit as the archetype, much of Detroit went to front wheel drive after 1980 in response to CAFE's 27.5 mpg mandate. The automobile industry faced a precipitous decline during the 1970s due to climbing inflation, energy prices, and complacency during the long years of prosperity in the 50s–60s. There was a loss of interest in sports and performance cars from 1972 onward, and newly mandated safety and emissions regulations caused many American cars to become heavy and suffer from drivability problems.[69]

Chrysler, the smallest of the Big Three, began suffering a growing financial crisis starting in 1976, but President Carter declined their request for a federal bailout so long as the company's existing management remained in place. In 1978, Lee Iacocca was hired as Chrysler president following his firing from Ford and inherited a company that was quickly teetering towards bankruptcy. Iacocca managed to convince a reluctant US Congress to approve Federal loan guarantees for the struggling auto manufacturer. Although Chrysler's troubles were the most well-publicized, Ford was also struggling and near bankruptcy by 1980. Only the huge General Motors managed to continue with business as usual.[70]

From 1972 to 1978, industrial productivity increased by only 1% a year (compared with an average growth rate of 3.2% from 1948 to 1955), while the standard of living in the United States fell to fifth in the world, with Denmark, West Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland surging ahead.[51]

Détente with USSR and China

editThe central goal of the Nixon administration was to radically transform relations with America's two chief rivals, the Soviet Union and China, by abandoning the policy of containment and adopting a policy of detente.[71] In February 1972, Nixon made a historic, nationally televised visit to China in an effort to establish diplomatic relations with the country. Relations with China had been largely hostile since the Korean War, and the United States still maintained that the Nationalist regime in Taiwan was the legitimate government of China. However, Nixon, once a staunch supporter of Chiang Kai-shek, came to increasingly believe in the value of restoring relations with China by the late 1960s as China's relationship with the Soviet Union had turned hostile after Mao's Cultural Revolution. After Nixon's trip to China, Nixon met Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and signed the SALT Treaty in Vienna.[72][73]

Watergate

editAfter a tumultuous internal battle, the Democrats nominated liberal South Dakota Senator George McGovern for president. Nixon effectively eliminated any major issue McGovern could build his platform on by ending the draft, initiating the withdrawal from Vietnam, and restoring ties with China. McGovern was ridiculed as the candidate of "acid, amnesty, and abortion" and on Election Day, Nixon carried every state except Massachusetts. Although, Democrats retained control of Congress.[74]

Nixon was investigated for the instigation and cover-up of the burglary of the Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate office complex In Washington. The House Judiciary Committee opened formal and public impeachment hearings against Nixon on May 9, 1974. Revelation after revelation astonished the nation, providing very strong evidence that Nixon had planned the cover-up of the burglary to protect his own reelection campaign. Rather than face impeachment by the House of Representatives and a possible conviction by the Senate, he resigned, effective August 9, 1974. His successor, Gerald R. Ford, a moderate Republican, issued a preemptive pardon of Nixon, ending the investigations of Nixon but eroding his own popularity.[75]

Ford administration

editAware that he had not been elected to either the office of president or vice-president, Gerald Ford addressed the nation immediately after he took the oath of office, pledging to be "President of all the people," and asking for their support and prayers, saying "Our long national nightmare is over."[76]

Ford's administration witnessed the final collapse of South Vietnam after the Democrat-controlled Congress voted to terminate all aid to that country. Ford's attempts to curb the growing problem of inflation met with little success, and his only solution seemed to be encouraging people to wear shirt buttons with the slogan WIN (Whip Inflation Now) on them. He also appointed a Supreme Court justice, John Paul Stevens, who retired in 2010.

During Ford's administration, the nation also celebrated its 200th birthday on July 4, 1976, widely observed with national, state, and local celebrations. The event brought some enthusiasm to an American populace that was feeling cynical and disillusioned from Vietnam, Watergate, and economic difficulties. Ford's pardon of Richard Nixon just before the 1974 midterm elections was not well received, and the Democrats made major gains, bringing to power a generation of young liberal activists, many of them suspicious of the military and the CIA. The Church Committee investigated numerous questionable activities performed by the CIA since the 1950s, including large-scale domestic surveillance, involuntary testing of psychotropic drugs on American citizens, and support for various unsavory Third World political figures. A massive six volume report on CIA actions over the last 20 years was released by Congress. As such, the amount of CIA domestic surveillance programs was dramatically cut from almost 5000 to 626 in 1976, and by the Reagan years, a mere 32 such programs were in operation. Most of the CIA agents responsible for these actions received no punishment and all served out their careers. Nonetheless, the murder of CIA agent Richard Welch by leftist militants in December 1975 provoked public outrage and Welch was given a hero's funeral and buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Welch's identity had been outed by Fifth Estate, an organization founded by writer and left-wing activist Norman Mailer, and the nature of his death merely resulted in increased public sympathy for the agency. Also by the mid-1970s, the Justice Department significantly reduced its list of subversive organizations (young hirees for government agencies in the 1970s were still being asked if they had served in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the 1930s). Other restrictions barring Communist Party members and homosexuals from government jobs were lifted. The FBI's extensive surveillance programs also became exposed to the public during the '70s. An unknown person or persons managed to steal documents from an FBI field office divulging that the bureau had since the 1960s spent $300,000 on 1000 informants to infiltrate the 2500 member Socialist Workers Party. Congress also passed an act forbidding American citizens from traveling abroad for the purpose of "assassination", although exactly what this meant was not clarified, and the act was subject to being revoked by the president at any time in the interest of national security.[77][78]

Carter administration

editThe Watergate scandal was still fresh in the voters' minds when former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, a Washington, D.C. outsider known for his integrity, prevailed over nationally better-known politicians in the Democratic Party presidential primaries in 1976. Faith in government was at a low ebb, and so was voter turnout. Carter became the first candidate from the Deep South to be elected president since the American Civil War. He stressed the fact that he was an outsider, not part of the Beltway political system, and that he was not a lawyer. Carter undertook various populist measures such as walking to the Capitol for his inauguration and wearing a sweater in the Oval Office to encourage energy conservation. The new president began his administration with a Democratic Congress. Democrats held a two-thirds supermajority in the House, and a filibuster-proof three-fifths supermajority in the Senate for the first time since the 89th United States Congress in 1965, and the last time until the 111th United States Congress in 2009. Carter's major accomplishments consisted of the creation of a national energy policy and the consolidation of governmental agencies, resulting in two new cabinet departments, the United States Department of Energy and the United States Department of Education. Congress successfully deregulated the trucking, airline, railway, finance, communications, and oil industries, and bolstered the social security system. In terms of representation, Carter appointed record numbers of women and minorities to significant governmental and judiciary posts, but nevertheless managed to feud with feminist leaders. Environmentalists promoted strong legislation on environmental protection, through the expansion of the National Park Service in Alaska, protecting 103 million acres of land. Carter failed to implement a national health plan or to reform the tax system, as he had promised in his campaign, and the Republicans won the House in the midterm elections.[79]

Following the post-OPEC embargo recession in 1974–75, economic growth resumed in 1976 and continued through 1978. Despite high rates of consumer spending, inflation and interest rates continued to be a persistent problem. But after the Iranian Hostage Crisis began in the spring of 1979, the US economy sunk into a deep recession, the worst since the Great Depression.

Emphasizing the energy crisis, President Carter mandated restrictions on speed limits and the heating of buildings. In 1979, Carter gave a nationally televised address in which he blamed the nation's troubles on the crisis of confidence among the American people. This "malaise speech" further damaged his reelection bid because it seemed to express a pessimistic outlook and blamed the American people for his own failed policies.[80]

Foreign affairs

editCarter's term is best known for the 444-day Iranian hostage crisis, and the move away from détente with the Soviet Union to a renewed Cold War.[79]

In foreign affairs, Carter's accomplishments consisted of the Camp David Accords, the Panama Canal Treaties, the creation of full diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China, and the negotiation of the SALT II Treaty. In addition, he championed human rights throughout the world and used human rights as the center of his administration's foreign policy.[81]

Although foreign policy remained quiet during Carter's first two years, the Soviet Union appeared to be getting stronger. It was expanding its influence into the Third World along with the help of allies such as Cuba, and the pace of Soviet military spending steadily rose. In 1979, Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan to prop up a Marxist regime there. In protest, Carter declared that the US would boycott the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. After nine years of fighting, the Soviets were unable to suppress Afghan rebels and pulled out of the country.[82][83] Soviet espionage of the US government, military, and major corporations during this period was relentless and little was done to stop it. In June 1978, Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn gave the commencement address to the graduating class of Harvard and blasted the US for its perceived failure to stand up to communist tyranny. Solzhenitsyn's speech sent shock waves through an America which was suffering from post-Vietnam syndrome and preferred to forget that the eight years of war in Southeast Asia had happened. Moscow continued to test the limits of how much they could get away with. During the mid-1970s, the Kremlin announced that it would allow a number of Russian Jews to move to the United States, however it came out too late that most of them were criminals and the entire exercise amounted to little more than a scheme by the USSR to empty their prisons of "anti-social elements". The result was a wave of organized crime in the Northeastern US, and pointless bureaucratic feuds in Washington meant that no action was taken to combat them until the 1990s. Cuba engaged in similar trickery during the 1970s by allowing political dissidents to move to the US, all of whom proved to be criminals, homosexuals, mental patients, and others who the Cubans deemed undesirables.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, American forces in Europe, neglected during the Vietnam War, were expected to face the increasingly powerful Warsaw Pact with 1950s-era weaponry. The US military faced a sort of psychological crisis in the aftermath of Vietnam and the ending of the draft, with low morale, racial tensions, and drug use. Entirely new methods of recruiting were attempted.[84][85]

The Carter Administration saw the sudden, violent end of the 2500-year-old Iranian monarchy. After the CIA-engineered coup in 1953 restored Shah Reza Pahlavi to power, he was feted as a US ally for the next quarter century and often referred to as a "champion" of the free world despite running a police state, and one that had great extremes of wealth and poverty, a small, Westernized middle class in Tehran contrasting with entire provinces that lacked running water or electricity, and where traditional lifestyles continued much as they had for centuries.

Up to 1970, the US had limited weapons sales to its Middle Eastern allies (which consisted mainly of Iran and Israel) in the hopes of preventing a regional arms race. The Nixon Administration lifted those restrictions that year, and the Shah obliged by purchasing expensive new military items, including F-14 fighter jets over the protests of Defense Department officials that Iran had no military need for the aircraft and selling them risked the possibility of compromising sensitive information. Pahlavi argued that he needed the military hardware to defend against the Soviet-backed Baathist regime in neighboring Iraq, until 1975 when he signed a nonaggression pact with Baghdad, after which both countries joined in on military attacks against the Kurds, who had also been a US ally. Despite owing his livelihood to Washington, the Shah nonetheless did not hesitate to join in with fellow Middle Eastern states in conspiring to raise oil prices in 1973.

The 2500th anniversary of Iranian monarchy was celebrated in 1975 with an enormous, expensive series of events in an extremely poor country, and the growing populist backlash against the Shah would erupt a few years later. Up until 1979, the State Department took it as writ that if the Shah were ever ousted, it would come from the small, Soviet-backed Tudeh Party. Anyone who knew enough about Iranian society could have predicted the arrival of the Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Khomeni, but such individuals were few and far between in the US government and intelligence agencies.

The high point of Carter's foreign-policy came in 1978, when he mediated the Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel, ending the state of war that had existed between those two countries since 1948.

In 1979, Carter completed the process begun by Nixon of restoring ties with China. Full diplomatic relations were established on January 1 of that year despite protests from Senator Barry Goldwater and some other conservative Republicans. Unofficial relations with Taiwan were maintained. Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping then visited the US in February 1979.

Carter also tried to place another cap on the arms race with a SALT II agreement in 1979, and faced the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Nicaraguan Revolution, and the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan. In 1979, Carter allowed the former Iranian Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi into the United States for medical treatment. In response Iranian militants seized the American embassy in the Iranian hostage crisis, taking 52 Americans hostage and demanding the Shah's return to Iran for trial and execution. The hostage crisis continued for 444 days and dominated the last year of Carter's presidency, ruining the President's tattered reputation for competence in foreign affairs. Carter's responses to the crisis, from a "Rose Garden strategy" of staying inside the White House to the failed military attempt to rescue the hostages, did not inspire confidence in the administration by the American people.

See also

edit- Cold War in Asia

- History of the United States (1980–1991)

- Fifth Party System

- Sixth Party System

- Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson

- Presidency of Richard Nixon

- Presidency of Gerald Ford

- Presidency of Jimmy Carter

- Timeline of the history of the United States (1950–1969)

- Timeline of the history of the United States (1970–1989)

References

edit- ^ Steven F. Hayward, The Age of Reagan, 1964–1980: The Fall of the Old Liberal Order (2001)

- ^ Seymour Martin Lipset, "Neoconservatism: Myth and reality. Archived 2017-02-13 at the Wayback Machine" Society 25.5 (1988): pp 9–13.

- ^ Colin Dueck, Hard Line: The Republican Party and U.S. Foreign Policy since World War II (2010).

- ^ Quoted in M. J. Heale, "The Sixties as History: A Review of the Political Historiography", Reviews in American History v. 33#1 (2005) 133–152 at p. 132

- ^ Robert Dallek, Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President (2004)

- ^ Irving Bernstein, Guns or Butter: The Presidency of Lyndon Johnson (1994)

- ^ David Edwin Harrell, Jr., Edwin S. Gaustad, John B. Boles, Sally Foreman Griffith, Randall M. Miller, Randall B. Woods, Unto a Good Land: A History of the American People (2005) pp 1052–53

- ^ James Reichley, Conservatives in an Age of Change: The Nixon and Ford Administrations (1982)

- ^ Alexander Hamilton (1984) intro to The Literature of Exhaustion, in The Friday Book.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (5 November 2007). "Brokaw Explores Another Turning Point, the '60s". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ^ J. Lull, and S. Hinerman, "The search for scandal' in J. Lull & S. Hinerman, eds. Media scandals: Morality and desire in the popular culture marketplace (1997) pp. 1–33.

- ^ Timothy E. Cook and Paul Gronke. "The skeptical American: Revisiting the meanings of trust in government and confidence in institutions." Journal of Politics 67.3 (2005): 784–803.

- ^ James O. Finckenauer, "Crime as a national political issue: 1964–76: From law and order to domestic tranquility." NPPA Journal 24.1 (1978): 13–27. Abstract Archived 2020-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James Davison Hunter, Culture wars: The struggle to control the family, art, education, law, and politics in America (1992).

- ^ Paul Boyer, "The Evangelical Resurgence in 1970s American Protestantism" in Schulman and Zelizer, eds. Rightward bound pp. 29–51.:

- ^ Stephen D. Johnson and Joseph B. Tamney, "The Christian Right and the 1980 presidential election. Archived 2019-12-30 at the Wayback Machine" Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (1982) 21#2: 123–131.

- ^ Jack M. Boom, Class, race, and the civil rights movement (1987).

- ^ David Farber, Taken hostage: The Iran hostage crisis and America's first encounter with radical Islam (Princeton UP, 2009).

- ^ W. Carl Biven, Jimmy Carter's economy: policy in an age of limits Archived 2018-08-10 at the Wayback Machine (U of North Carolina Press, 2003).

- ^ Bruce J. Schulman and Julian E. Zelizer, eds. Rightward Bound: Making America Conservative in the 1970s (Harvard UP, 2008) pp. 1–10.

- ^ Andrew Busch, Regan's victory: the presidential election of 1980 and the rise of the right (UP of Kansas, 2005).

- ^ Arthur Marwick (1998). "The Sixties–Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States, c. 1958 – c. 1974 (excerpt from book)". The New York Times: Books. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

...black civil rights; youth culture and trend-setting by young people; idealism, protest, and rebellion; the triumph of popular music based on Afro-American models and the emergence of this music as a universal language, with the Beatles as the heroes of the age...

- ^ Katy Marquardt (August 13, 2009). "10 Places to Relive the '60s". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 2009-10-11. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

Many of the most crucial events of the 1960s—including the civil rights victories, antiwar protests, and the sweeping cultural revolution—left few physical traces.

- ^ Sanford D. Horwitt (March 22, 1998). "The Children". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

He notes that in the 1950s, black protests were pursued mainly through the courts and led by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In the 1960s, the emphasis was on direct action led not only by Martin Luther King Jr. but also by an unlikely array of young activists, many of them college students in Nashville, where Halberstam was a young reporter for the Tennessean at the time.

- ^ Hugh Davis Graham, The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy, 1960–1972 (1990)

- ^ Thomas E. Cavanagh, "Changes in American voter turnout, 1964–1976." Political Science Quarterly (1981): 53–65. in JSTOR Archived 2022-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gregory L. Schneider, The Conservative Century: From Reaction to Revolution (2009) pp. 91–118

- ^ Irving Bernstein, Guns or Butter: The Presidency of Lyndon Johnson 1994 (1994)

- ^ Bernstein, Guns or Butter: The Presidency of Lyndon Johnson 1994 (1994)

- ^ Peter Braunstein, and Michael William Doyle, eds., Imagine nation: the American counterculture of the 1960s and '70s (2002).

- ^ Pinker, Steven (2011). The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. New York: Penguin Group. pp. 92, 106–128. ISBN 978-0143122012.

- ^ Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 144–147. ISBN 978-0684832838.

- ^ Kennedy to Johnson, "Memorandum for Vice President," Archived 2017-01-31 at the Wayback Machine 20 April 1961.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (1961-05-25). "Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs". Historical Resources. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. p. 4. Archived from the original on March 16, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ Gary Donaldson, America at war since 1945 (1996) p. 96

- ^ Niels Bjerre-Poulsen, Right face: organizing the American conservative movement 1945–65 (2002) p. 267

- ^ Mark W. Woodruff, Unheralded Victory: The Defeat of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, 1961–1973 (2006) p. 56

- ^ Herbert Y. Schandler, America in Vietnam: The War That Couldn't Be Won (2009)

- ^ John E. Bodnar (1996). Bonds of Affection: Americans Define Their Patriotism. Princeton University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-691-04396-8. Archived from the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Charles DeBenedetti, An American Ordeal: The Antiwar Movement of the Vietnam Era (1990)

- ^ Lewis L. Gould, 1968: The Election That Changed America (2010) pp. 7–33

- ^ Gould, 1968: The Election That Changed America (2010) pp. 129–55

- ^ Glenda Riley, Inventing the American Woman: An Inclusive History (2001)

- ^ Angela Howard Zophy, ed. Handbook of American Women's History(2nd ed. 2000).

- ^ Donald T. Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman's Crusade (2005)

- ^ Mansbridge, Jane J. (1986). Why We Lost the ERA. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226503585.

- ^ Donald T. Critchlow, Intended Consequences: Birth Control, Abortion, and the Federal Government in Modern America (2001)

- ^ "770,000 Women Turned Down in 1975". The New York Times. January 2, 1977. Archived from the original on February 5, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ "Abortion in the United States" (PDF). harvard.edu. 1998-10-20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ John C. Whitaker, "Nixon's domestic policy: Both liberal and bold in retrospect", Presidential Studies Quarterly, Winter 1996, Vol. 26 Issue 1, pp. 131–53

- ^ a b c d The Unfinished Journey: America Since World War II by William H. Chafe

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Hamill, Pete (1969-04-14). "Pete Hamill on the Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class". Nymag.com. New York Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-11-30. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ "Peter Schrag, "The Forgotten American," 1969". Web.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ Marisa Chappell (2011). The War on Welfare: Family, Poverty, and Politics in Modern America. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8122-2154-1. Archived from the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Judith Stein (2010). Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies. Yale University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-300-16329-2. Archived from the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Robert Bruno (1999). Steelworker Alley: How Class Works in Youngstown. Cornell University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8014-8600-5. Archived from the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Harry G. Summers, "The Vietnam Syndrome and the American People." Journal of American Culture (1994) 17#1 pp. 53–58.

- ^ Roger Gomes (2015). Proceedings of the 1995 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference. Springer. p. 171. ISBN 978-3-319-13147-4.

- ^ George C. Kohn (2001). The New Encyclopedia of American Scandal. Infobase Publishing. p. 382. ISBN 978-1-4381-3022-4.

- ^ Howard M. Wachtel (2013). Labor and the Economy. Elsevier. pp. 350–51. ISBN 978-1-4832-6341-0.

- ^ Gregory L. Schneider (2009). The Conservative Century: From Reaction to Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 127–30. ISBN 978-0-7425-4284-6.

- ^ Michael W. Flamm, Law and order: Street crime, civil unrest, and the crisis of liberalism in the 1960s (2005).

- ^ Martin Shefter, Political crisis/fiscal crisis: The collapse and revival of New York City (Columbia University Press, 1992).

- ^ David Horowitz, Jimmy Carter and the Energy Crisis of the 1970s: The" Crisis of Confidence" Speech of July 15, 1979: a Brief History with Documents (2005).

- ^ Yanek Mieczkowski, Gerald Ford and the Challenges of the 1970s (University Press of Kentucky, 2005).

- ^ David Halberstam, The Reckoning (1986) excerpt Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine compares Ford and Nissan in the 1970s.

- ^ Lee Iacocca and William Novak, Iacocca: an autobiography (1986)

- ^ Daniel J. Sargent, A Superpower Transformed: The Remaking of American Foreign Relations in the 1970s (2015)

- ^ Margaret MacMillan, Nixon in China (2009).

- ^ Robert S. Litwak, Détente and the Nixon doctrine: American foreign policy and the pursuit of stability, 1969–1976 (1986).

- ^ Theodore H. White, The Making of the President 1972 (1973)

- ^ Theodore H. White, Breach of faith: The fall of Richard Nixon (1975)

- ^ Ford, Gerald R. (August 9, 1974). "Gerald R. Ford's Remarks on Taking the Oath of Office as President". Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Archived from the original on August 13, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ James Reichley. Conservatives in an Age of Change: The Nixon and Ford Administrations (1982)

- ^ John Robert Greene, The Presidency of Gerald R. Ford (1995)

- ^ a b Julian E. Zelizer, Jimmy Carter (2010)

- ^ Kevin Mattson, "What the Heck Are You Up To, Mr. President?": Jimmy Carter, America's "Malaise," and the Speech That Should Have Changed the Country (2010)

- ^ Scott Kaufman, Plans unraveled: the foreign policy of the Carter administration (2008).

- ^ John Dumbrell, American foreign policy: Carter to Clinton (1997).

- ^ Odd Arne Westad, ed. The Fall of Détente: Soviet-American Relations during the Carter Years (1997).

- ^ Beth Bailey, "The Army in the marketplace: Recruiting an all-volunteer force". Journal of American History (2007) 94#1 pp: 47–74. JSTOR 25094776.

- ^ Beth Bailey, America's Army: Making the All-Volunteer Force (2009)

Further reading

edit- Bernstein, Irving. Guns or Butter: The Presidency of Lyndon Johnson 1994.

- Black, Conrad. Richard M. Nixon: A Life in Full (2007) 1150pp;

- Branch, Taylor. Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–65 (1999) excerpt and text search Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Branch, Taylor. At Canaan's Edge: America in the King Years, 1965–68 (2007)

- Dallek, Robert. Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961–1973 (1998) online edition vol 2 Archived 2012-04-27 at the Wayback Machine; also: Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President (2004). A 400-page abridged version of his 2 volume scholarly biography, online edition of short version Archived 2012-05-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- Farber, David, and Beth Bailey, eds. The Columbia Guide to America in the 1960s (2001).

- Frum, David. How We Got Here (2000)

- Graham, Hugh Davis. The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy, 1960–1972 (1990)

- Hays, Samuel P. A history of environmental politics since 1945 (2000).

- Hayward, Steven F. The Age of Reagan, 1964–1980: The Fall of the Old Liberal Order (2001)

- Heale, M. J. "The Sixties as History: A Review of the Political Historiography", Reviews in American History v. 33#1 (2005) 133–152

- Hunt, Andrew. "When Did the Sixties Happen?" Journal of Social History 33 (Fall 1999): 147–61.

- Kaufman, Burton Ira. The Presidency of James Earl Carter, Jr. (1993), the best survey of his administration

- Kirkendall, Richard S. A Global Power: America Since the Age of Roosevelt (2nd ed. 1980) university textbook 1945–80 full text online free

- Kruse, Kevin M. and Julian E. Zelizer. Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974 (WW Norton, 2019), scholarly history. excerpt Archived 2022-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Olson, James S. ed. Historical Dictionary of the 1970s (1999) excerpt Archived 2022-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Marwick, Arthur. The Sixties: Cultural Transformation in Britain, France, Italy and the United States, c. 1958 – c. 1974 (1998), international perspective excerpt and text search Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Matusow, Allen J. The Unraveling of America: A History of Liberalism in the 1960s (1984) excerpt and text search Archived 2022-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Nixon, Richard M. (1978). RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon. ISBN 978-0-671-70741-5. online, a primary source

- Olson, James Stuart, ed. The Vietnam War: Handbook of the literature and research (Greenwood, 1993) excerpt Archived 2010-10-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Paterson, Thomas G. Meeting the Communist Threat: Truman to Reagan (1988),

- Patterson, James. Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974 (Oxford History of the United States) (1997)

- Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus (2001) political narrative of 1960–64

- Perlstein, Rick (2008). Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-4302-5. political narrative of 1964-72

- Sargent, Daniel J. A Superpower Transformed: The Remaking of American Foreign Relations in the 1970s (2015)

- Schulman, Bruce J., ed. Rightward bound: Making America conservative in the 1970s (Harvard University Press, 2008).

- Suri, Jeremi. Henry Kissinger and the American Century (2007)

- Vandiver, Frank E. Shadows of Vietnam: Lyndon Johnson's Wars (1997) online edition Archived 2012-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Wilentz, Sean. The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008 (2007) excerpt and text search Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine