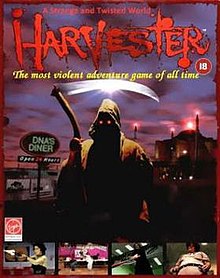

Harvester is a 1996 point-and-click adventure game written and directed by Gilbert P. Austin, known for its violent content, cult following, and examination of violence.[2] Players take on the role of Steve Mason, an eighteen-year-old man who awakens in a Texas town in 1953 with no memory of who he is and a vague sense he does not belong there. Over the course of the next week, he is coerced or manipulated into performing a series of seemingly mundane tasks with increasingly violent consequences at the behest of The Order of the Harvest Moon, a cult-like organization which seems to dominate the town and which promises to reveal the truth about Steve and his presence in Harvest.

| Harvester | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | DigiFX Interactive |

| Publisher(s) |

|

| Producer(s) | Lee Jacobson |

| Designer(s) | Gilbert P. Austin |

| Platform(s) | DOS, Microsoft Windows, Linux |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Interactive film, point-and-click adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Gameplay

editThe game utilizes a point and click interface. Players must visit various locations within the game's fictional town of Harvest via an overhead map. By speaking to various townspeople and clicking on special "hotspots", players can learn information and collect items that progress the game's story and play. Harvester also features a fighting system where players can attack other characters by selecting a weapon and then clicking on the target. Both the target and the player's character have a limited amount of health available, allowing for either the player or the target to die. Players can choose to progress through the game by solving puzzles or by killing one of the non-playable characters.

Plot

editTeenager Steve Mason awakens in the small Texas farming town of Harvest in the year 1953, with no memories of his past or who he is. Exploring his home, he discovers that he does not recognize his mother or younger brother, both of whom act strangely—his mother compulsively bakes cookies for a charity event a week away, causing her to throw out each subsequent batch; and his brother obsessively watches an ultra-violent cowboy show that is the only program broadcast on Harvest televisions.

Exploring the town, Steve discovers Harvest is populated by hostile, strange individuals whom he likens to facsimiles or parodies of real people. Steve learns that no one believes him to genuinely be amnesiac, with every citizen he meets responding to his pleas for help with the canned response "You always were a kidder, Steve." Everyone in town encourages Steve to join the Lodge, a large building (reminiscent of the Hagia Sophia) located at the center of town that serves as the headquarters of the Order of the Harvest Moon, which is the sociopolitical center of life in Harvest and whose members act in lieu of a mayor or city council.

Learning that he is set to be married in two weeks, Steve goes to meet his fiancée, Stephanie Pottsdam, the daughter of Mr. Pottsdam, an unemployed man who hopes to get a job alongside Steve's father working in Harvest's meat packing plant and who openly expresses his lust for his own daughter. Meeting Stephanie, Steve finds that she, too, has amnesia, and woke up the same morning as him with no idea of how she got to Harvest. The two form an alliance to figure out their past and escape the town.

Steve visits the Sergeant at Arms at the Lodge, who tells him that all of his questions will be answered inside the building, and sets about giving him a series of tasks that serve as initiation rites. Over the course of the next week, Steve is given a new "task" each day, beginning with petty acts of vandalism that escalate to theft and arson, with each task having unforeseen, tragic circumstances that usually result in someone's accidental death, murder, or suicide. Meanwhile, driven by their mutual fear and reliance on one another, Steve and Stephanie become lovers.

On the final day of his initiation, Steve discovers a mutilated skull and spinal cord in Stephanie's bed, which the Sergeant at Arms tells him is his invitation to the Lodge. Venturing inside, Steve discovers that the Lodge is composed of a series of rooms called "Temples" which serve as mordant burlesques of real civic locations (including a living room with a dead family and a kitchen where a chef prepares human meat) and whose inhabitants challenge him with a series of puzzles meant to teach lessons integral to understanding the precepts of the lodge. Each "lesson" turns out to be an inversion of traditional morality, including the futility of charity, the uselessness of the elderly, and the benefits of lust and vanity.

At the highest level of the Lodge, the Sergeant at Arms presents a still-living Stephanie and explains that Harvest is an elaborate virtual reality simulator being operated by a group of scientists in the 1990s to determine if it is possible to turn average humans into serial killers. Steve and Stephanie are the only real people in the simulation, and everything Steve has experienced has been intended to warp his reality and break down his inhibitions to prepare him for life as a serial killer. The Sergeant offers him two options: murder Stephanie, committing his first real crime and accepting a future as a murderer; or refuse, in which case the scientists will render both Steve and Stephanie brain dead in the laboratory. Should Steve choose the second option, the Sergeant informs him he and Stephanie will experience an entire lifetime of happiness in the Harvest simulator in the seconds before their deaths in the real world.

If the player chooses to kill Stephanie, Steve bludgeons Stephanie to death and removes her skull and spinal cord. After the murder is complete, Steve awakens in the laboratory and gleefully informs the scientists that he enjoyed the experience. Hitchhiking home, he murders the driver who picks him up. Later, while he plays a violent videogame in his bedroom, Steve's mother chastises him that doing so will induce violent impulses in him. Steve laughs as the camera enters his throat and stomach, revealing the dissolving body parts of the driver he killed earlier.

If the player chooses to spare Stephanie, the Sergeant at Arms performs an impromptu wedding in the chapel before letting the pair go. Steve and Stephanie buy a home, have a child, and grow old together before dying peacefully and being buried in the Harvest cemetery. In real life, the scientists express disappointment at the results of their experiment as they look on at the pair's dead bodies.

Development and controversy

editHarvester was developed by FutureVision (renamed DigiFX by the time of the game's release). Writer-director Gilbert P. Austin recounted:

My feeling was that FutureVision, being a small company, would need something "high concept" to compete with the industry giants of the time, and I argued that Harvester was exactly that idea. It was really the only idea that I pitched. I remember that it came to me in a flash. That's how I get a lot of my ideas, in creative rushes where I can barely write fast enough to get it all down. ... The concept of Harvester, the idea that at the end of the game I wanted the player to mull over whether he had internalized the over-the-top violence and surreal imagery of the game in the same manner that Steve had, and the primary ending... all this was in the initial concept that I jotted down in one of those small reporter spiral notepads in about 30 minutes. That's what I pitched to FutureVision, and they bought it.[3]

Harvester was announced at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in January 1994 in Las Vegas.[3] The game had a budget of $1 million.[4] The video footage was filmed in the back warehouse of publisher Merit Software.[3] Though he was only contracted as the game's writer, Austin voluntarily directed the filming to ensure it stayed true to his vision for the game.[3] Austin finished the creative work in Autumn 1994 and moved on to other projects, leaving producer Lee Jacobson in sole charge of the remaining development.[3] The game was set to be released the same year but the programming took two years to finish, and it became a commercial failure.[3]

In a December 1996 press conference, family psychologist David Walsh released a list of excessively violent games. Jacobson publicly demanded that Harvester, which was not included in Walsh's list, be added to it.[5] Gaming journalist Christian Svensson described Jacobson's actions as "shameless", and did not refer to Jacobson, DigiFX, or Harvester by name so as not to provide positive reinforcement for publicity seeking.[6]

In Germany, the game was banned.[7]

The game was designed by DigiFX Interactive and published by Merit Studios in 1996.[8] On March 6, 2014, Lee Jacobson re-released it on GOG.com,[9] for PC and Mac. On April 4, 2014, Nightdive Studios re-released it on Steam for PC and Linux.[10]

Reception

edit| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 53/100[11] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Adventure Gamers | [12] |

| AllGame | [13] |

| GameSpot | 6.8/10[14] |

| PC Gamer (US) | 82/100[15] |

| Entertainment Weekly | B+[16] |

Harvester received "mixed or average" reviews, according to review aggregator Metacritic.[11] PC Gamer gave Harvester a positive review upon its initial release,[15] but panned it in a 2011 review where they called it the "goriest, most confusing, and above all stupidest horror game ever."[17] Allgame remarked that the game's delayed release negatively impacted its reception, as the game felt dated when it was finally released. They felt that this was indicative of the game as a whole, as "conversations with characters are frustrating and often make little sense, plus the manner in which the plot develops is disappointing. ... there are things that are never explained, and the final third of the game is dull and pointless."[13] GameSpot's review was mixed, as they felt that there was "nothing actually revolutionary going on in Harvester" but praised the game's full-motion video segments as "truly disturbing" and commented that it had "tried-and-true adventure mechanics with entertaining twists".[14]

Entertainment Weekly commented that "this gratuitously violent game doesn’t make much sense, but it is a lot of twisted fun."[16]

References

edit- ^ "Online Gaming Review". 1997-02-27. Archived from the original on 1997-02-27. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ^ Elston, Brett (30 October 2009). "The bloodiest games you've never played". Games Radar. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Malin, Aarno. "Inside Harvester - A Fan Interview with Gilbert P. Austin". GOG.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ Curtis, Gregory (March 1995). "A bloody game". Texas Monthly. Archived from the original on November 5, 2024. Retrieved October 17, 2024 – via Gale Research.

- ^ "What Is Senator Lieberman's Problem with Videogames?". Next Generation. No. 28. Imagine Media. April 1997. p. 11.

- ^ Svensson, Christian (March 1997). "Lieberman Back in Action". Next Generation. No. 27. Imagine Media. p. 28.

- ^ "Retro Gaming: Harvester (1996)". Weird Retro. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- ^ Computer Gaming World, Volumes 150-153. Golden Empire Publications. 1997. Archived from the original on 2017-03-23. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- ^ GOG.com (2014-03-06). "Release: Harvester". CD Projekt. Archived from the original on 2014-05-13. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ^ Valve (2014-04-04). "Now Available on Steam - Harvester". Steam. Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ^ a b "Harvester for PC Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Indovina, Kurt (October 30, 2015). "Harvester Review". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ a b House, Matthew. "Harvester". Allgame. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ a b Hudak, Chris (August 29, 1996). "Harvester Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Gamer, PC (April 27, 2014). "Harvester review - December 1996, US edition". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Harvester". EW.com. Archived from the original on 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ Cobbett, Richard (May 14, 2011). "Saturday Crapshoot: Harvester". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.