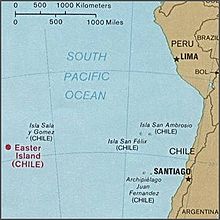

Easter Island is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands.[1] Its closest inhabited neighbours are the Chilean Juan Fernandez Islands, 1,850 km (1,150 mi) to the east, with approximately 850 inhabitants.[citation needed] The nearest continental point lies in central Chile near Concepción, at 3,512 kilometres (2,182 mi). Easter Island's latitude is similar to that of Caldera, Chile, and it lies 3,510 km (2,180 mi) west of continental Chile at its nearest point (between Lota and Lebu in the Biobío Region). Isla Salas y Gómez, 415 km (258 mi) to the east, is closer but is uninhabited. The Tristan da Cunha archipelago in the southern Atlantic competes for the title of the most remote island, lying 2,430 km (1,510 mi) from Saint Helena island and 2,816 km (1,750 mi) from the South African coast.

The island is about 24.6 km (15.3 mi) long by 12.3 km (7.6 mi) at its widest point; its overall shape is triangular. It has an area of 163.6 km2 (63.2 sq mi), and a maximum elevation of 507 m (1,663 ft) above mean sea level. There are three Rano (freshwater crater lakes), at Rano Kau, Rano Raraku and Rano Aroi, near the summit of Terevaka, but no permanent streams or rivers.

Geology

editEaster Island is a volcanic island, consisting mainly of three extinct coalesced volcanoes: Terevaka (altitude 507 metres) forms the bulk of the island, while two other volcanoes, Poike and Rano Kau, form the eastern and southern headlands and give the island its roughly triangular shape. Lesser cones and other volcanic features include the crater Rano Raraku, the cinder cone Puna Pau and many volcanic caves including lava tubes.[2] Poike used to be a separate island until volcanic material from Terevaka united it to the larger whole. The island is dominated by hawaiite and basalt flows which are rich in iron and show affinity with igneous rocks found in the Galápagos Islands.[3]

Easter Island and surrounding islets, such as Motu Nui and Motu Iti, form the summit of a large volcanic mountain rising over 2,000 m (6,600 ft) from the sea bed. The mountain is part of the Salas y Gómez Ridge, a (mostly submarine) mountain range with dozens of seamounts, formed by the Easter hotspot. The range begins with Pukao and next Moai, two seamounts to the west of Easter Island, and extends 2,700 km (1,700 mi) east to the Nazca Ridge. The ridge was formed by the Nazca Plate moving over the Easter hotspot.[4]

Located about 350 km (220 mi) east of the East Pacific Rise, Easter Island lies within the Nazca Plate, bordering the Easter Microplate. The Nazca-Pacific relative plate movement due to the seafloor spreading, amounts to about 150 mm (5.9 in) per year. This movement over the Easter hotspot has resulted in the Easter Seamount Chain, which merges into the Nazca Ridge further to the east. Easter Island and Isla Salas y Gómez are surface representations of that chain. The chain has progressively younger ages to the west. The current hotspot location is speculated to be west of Easter Island, amidst the Ahu, Umu and Tupa submarine volcanic fields and the Pukao and Moai seamounts.[5]

Easter Island lies atop the Rano Kau Ridge, and consists of three shield volcanoes with parallel geologic histories. Poike and Rano Kau exist on the east and south slopes of Terevaka, respectively. Rano Kau developed between 0.78 and 0.46 Ma from tholeiitic to alkalic basalts. This volcano possesses a clearly defined summit caldera. Benmoreitic lavas extruded about the rim from 0.35 to 0.34 Ma. Finally, between 0.24 and 0.11 Ma, a 6.5 km (4.0 mi) fissure developed along a NE–SW trend, forming monogenetic vents and rhyolitic intrusions. These include the cryptodome islets of Motu Nui and Motu Iti, the islet of Motu Kao Kao, the sheet intrusion of Te Kari Kari, the perlitic obsidian Te Manavai dome and the Maunga Orito dome.[5]

Poike formed from tholeiitic to alkali basalts from 0.78 to 0.41 Ma. Its summit collapsed into a caldera which was subsequently filled by the Puakatiki lava cone pahoehoe flows at 0.36 Ma. Finally, the trachytic lava domes of Maunga Vai a Heva, Maunga Tea Tea, and Maunga Parehe formed along a NE-SW trending fissure.[5]

Terevaka formed around 0.77 Ma of tholeiitic to alkali basalts, followed by the collapse of its summit into a caldera. Then at about 0.3Ma, cinder cones formed along a NNE-SSW trend on the western rim, while porphyritic benmoreitic lava filled the caldera, and pahoehoe flowed towards the northern coast, forming lava tubes, and to the southeast. Lava domes and a vent complex formed in the Maunga Puka area, while breccias formed along the vents on the western portion of Rano Aroi crater. This volcano's southern and southeastern flanks are composed of younger flows consisting of basalt, alkali basalt, hawaiite, mugearite, and benmoreite from eruptive fissures starting at 0.24 Ma. The youngest lava flow, Roiho, is dated at 0.11 Ma. The Hanga O Teo embayment is interpreted to be a 200 m high landslide scarp.[5]

Rano Raraku and Maunga Toa Toa are isolated tuff cones of about 0.21 Ma. The crater of Rano Raraku contains a freshwater lake. The stratified tuff is composed of sideromelane, slightly altered to palagonite, and somewhat lithified. The tuff contains lithic fragments of older lava flows. The northwest sector of Rano Raraku contains reddish volcanic ash.[5] According to Bandy, "...all of the great images of Easter Island are carved from" the light and porous tuff from Rano Raraku. A carving was abandoned when a large, dense and hard lithic fragment was encountered. However, these lithics became the basis for stone hammers and chisels. The Puna Pau crater contains an extremely porous pumice, from which was carved the Pukao "hats". The Maunga Orito obsidian was used to make the "mataa" spearheads.[6]

In the first half of the 20th century, steam reportedly came out of the Rano Kau crater wall. This was photographed by the island's manager, Mr. Edmunds.[7]

Climate

editUnder the Köppen climate classification, the climate of Easter Island is classified as a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) that borders on a tropical rainforest climate (Af). The lowest temperatures are recorded in July and August (minimum 15 °C or 59 °F) and the highest in February (maximum temperature 28 °C or 82.4 °F[8]), the summer season in the southern hemisphere. Winters are relatively mild. The rainiest month is May, though the island experiences year-round rainfall.[9] Easter Island's isolated location exposes it to winds which help to keep the temperature fairly cool. Precipitation averages 1,118 millimetres or 44 inches per year. Occasionally, heavy rainfall and rainstorms strike the island. These occur mostly in the winter months (June–August). Since it is close to the South Pacific High and outside the range of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, cyclones and hurricanes do not occur around Easter Island.[10] There is significant temperature moderation due to its isolated position in the middle of the ocean.

Climate data

edit| Climate data for Easter Island (Mataveri International Airport) 1981–2010, extremes 1912–1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 70.4 (2.77) |

80.2 (3.16) |

99.2 (3.91) |

139.9 (5.51) |

143.4 (5.65) |

110.3 (4.34) |

130.1 (5.12) |

104.8 (4.13) |

108.5 (4.27) |

90.6 (3.57) |

75.4 (2.97) |

75.6 (2.98) |

1,228.1 (48.35) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.3 | 10.1 | 10.8 | 12.1 | 12.6 | 11.5 | 12.1 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 8.4 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 126.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 77 | 77 | 78 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 274 | 239 | 229 | 193 | 173 | 145 | 156 | 172 | 179 | 213 | 222 | 242 | 2,437 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile[11] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (precipitation days 1981–2010),[12] Ogimet (sun 1981–2010)[13] Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes and humidity)[14] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

editEaster Island, together with its closest neighbour, the tiny island of Isla Salas y Gómez 415 km (258 mi) farther east, is recognized by ecologists as a distinct ecoregion, the Rapa Nui subtropical broadleaf forests. The original subtropical moist broadleaf forests are now gone, but paleobotanical studies of fossil pollen, tree moulds left by lava flows, and root casts found in local soils indicate that the island was formerly forested, with a range of trees, shrubs, ferns, and grasses. A large extinct palm, Paschalococos disperta, related to the Chilean wine palm (Jubaea chilensis), was one of the dominant trees as attested by fossil evidence. Like its Chilean counterpart it probably took close to 100 years to reach adult height. The Polynesian rat, which the original settlers brought with them, played a very important role in the disappearance of the Rapa Nui palm. Although some may believe that rats played a major role in the degradation of the forest, less than 10% of palm nuts show teeth marks from rats. The remains of palm stumps in different places indicate that humans caused the trees to fall because in large areas, the stumps were cut efficiently.[15] In 2018, a New York Times article announced that Easter Island is eroding.[16]

The clearance of the palms to make the settlements led to their extinction almost 350 years ago.[17] The toromiro tree (Sophora toromiro) was prehistorically present on Easter Island, but is now extinct in the wild. However, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Göteborg Botanical Garden are jointly leading a scientific program to reintroduce the toromiro to Easter Island. With the palm and the toromiro virtually gone, there was considerably less rainfall as a result of less condensation. After the island was used to feed thousands of sheep for almost a century, by the mid-1900s the island was mostly covered in grassland with nga'atu or bulrush (Schoenoplectus californicus tatora) in the crater lakes of Rano Raraku and Rano Kau. The presence of these reeds, which are called totora in the Andes, was used to support the argument of a South American origin of the statue builders, but pollen analysis of lake sediments shows these reeds have grown on the island for over 30,000 years.[citation needed] Before the arrival of humans, Easter Island had vast seabird colonies containing probably over 30 resident species, perhaps the world's richest.[18] Such colonies are no longer found on the main island. Fossil evidence indicates six species of land birds (two rails, two parrots, one owl, and one heron), all of which have become extinct.[19] Five introduced species of land bird are known to have breeding populations (see List of birds of Easter Island).

Lack of studies results in poor understanding of the oceanic fauna of Easter Island and waters in its vicinity; however, possibilities of undiscovered breeding grounds for humpback, southern blue and pygmy blue whales including Easter Island and Isla Salas y Gómez have been considered.[20] Potential breeding areas for fin whales have been detected off northeast of the island as well.[21]

- Vegetation on the island

-

Satellite view of Easter Island 2019. The Poike peninsula is on the right.

-

Digital recreation of its ancient landscape, with tropical forest and palm trees

-

Hanga Roa seen from Terevaka, the highest point of the island

-

View of Rano Kau and Pacific Ocean

The immunosuppressant drug sirolimus was first discovered in the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus in a soil sample from Easter Island. The drug is also known as rapamycin, after Rapa Nui.[22] It is now being studied for extending longevity in mice.[23]

Trees are sparse, rarely forming natural groves, and it has been argued whether native Easter Islanders deforested the island in the process of erecting their statues,[24] and in providing sustenance for an overconsumption of natural resources from a overcrowded island.[citation needed] Experimental archaeology demonstrated that some statues certainly could have been placed on Y-shaped wooden frames called miro manga erua and then pulled to their final destinations on ceremonial sites.[24] Other theories involve the use of "ladders" (parallel wooden rails) over which the statues could have been dragged.[25] Rapa Nui traditions metaphorically refer to spiritual power (mana) as the means by which the moai were "walked" from the quarry. Recent experimental recreations have proven that it is fully possible that the moai were literally walked from their quarries to their final positions by use of ropes, casting doubt on the role that their existence plays in the environmental collapse of the island.[26]

Given the island's southern latitude, the climatic effects of the Little Ice Age (about 1650 to 1850) may have exacerbated deforestation, although this remains speculative.[24] Many researchers[27] point to the climatic downtrend caused by the Little Ice Age as a contributing factor to resource stress and to the palm tree's disappearance. Experts, however, do not agree on when the island's palms became extinct.

Jared Diamond dismisses past climate change as a dominant cause of the island's deforestation in his book Collapse which assesses the collapse of the ancient Easter Islanders.[28] Influenced by Heyerdahl's romantic interpretation of Easter's history, Diamond insists that the disappearance of the island's trees seems to coincide with a decline of its civilization around the 17th and 18th centuries. He notes that they stopped making statues at that time and started destroying the ahu. But the link is weakened because the Bird Man cult continued to thrive and survived the great impact caused by the arrival of explorers, whalers, sandalwood traders, and slave raiders.

Midden contents show that the main source of protein was tuna and dolphin. With the loss of the trees, there was a sudden drop in the quantities of fish bones found in middens as the islanders lost the means to construct fishing vessels, coinciding with a large increase in bird bones. This was followed by a decrease in the number of bird bones as birds lost their nesting sites or became extinct. A new style of art from this period shows people with exposed ribs and distended bellies, indicative of malnutrition, and it is around this time that many islanders moved to live in fortified caves, and the first signs of warfare and cannibalism appear.

Soil erosion because of lack of trees is apparent in some places. Sediment samples document that up to half of the native plants had become extinct and that the vegetation of the island drastically altered. Polynesians were primarily farmers, not fishermen, and their diet consisted mainly of cultivated staples such as taro root, sweet potato, yams, cassava, and bananas. With no trees to protect them, sea spray led to crop failures exacerbated by a sudden reduction in freshwater flows. There is evidence that the islanders took to planting crops in caves beneath collapsed ceilings and covered the soil with rocks to reduce evaporation. Cannibalism occurred on many Polynesian islands, sometimes in times of plenty as well as famine. Its presence on Easter Island (based on human remains associated with cooking sites, especially in caves) is supported by oral histories.[citation needed]

Benny Peiser[29] noted evidence of self-sufficiency when Europeans first arrived. The island still had smaller trees, mainly toromiro, which became extinct in the wild in the 20th century probably because of slow growth and changes in the island's ecosystem. Cornelis Bouman, Jakob Roggeveen's captain, stated in his logbook, "... of yams, bananas and small coconut palms we saw little and no other trees or crops." According to Carl Friedrich Behrens, Roggeveen's officer, "The natives presented palm branches as peace offerings." According to ethnographer Alfred Mètraux, the most common type of house was called "hare paenga" (and is known today as "boathouse") because the roof resembled an overturned boat. The foundations of the houses were made of buried basalt slabs with holes for wooden beams to connect with each other throughout the width of the house. These were then covered with a layer of totora reed, followed by a layer of woven sugarcane leaves, and lastly a layer of woven grass.

Peiser claims that these reports indicate that large trees existed at that time, which is perhaps contradicted by the Bouman quote above. Plantations were often located farther inland, next to foothills, inside open-ceiling lava tubes, and in other places protected from the strong salt winds and salt spray affecting areas closer to the coast. It is possible many of the Europeans did not venture inland. The statue quarry, only one kilometre (5⁄8 mile) from the coast with an impressive cliff 100 m (330 ft) high, was not explored by Europeans until well into the 19th century.

Easter Island has suffered from heavy soil erosion in recent centuries, perhaps aggravated by agriculture and massive deforestation. This process seems to have been gradual and may have been aggravated by sheep farming throughout most of the 20th century. Jakob Roggeveen reported that Easter Island was exceptionally fertile. "Fowls are the only animals they keep. They cultivate bananas, sugar cane, and above all sweet potatoes." In 1786 Jean-François de La Pérouse visited Easter Island and his gardener declared that "three days' work a year" would be enough to support the population. Rollin, a major in the Pérouse expedition, wrote, "Instead of meeting with men exhausted by famine... I found, on the contrary, a considerable population, with more beauty and grace than I afterwards met in any other island; and a soil, which, with very little labor, furnished excellent provisions, and in an abundance more than sufficient for the consumption of the inhabitants."[31]

According to Diamond, the oral traditions (the veracity of which has been questioned by Routledge, Lavachery, Mètraux, Peiser, and others) of the current islanders seem obsessed with cannibalism, which he offers as evidence supporting a rapid collapse. For example, he states, to severely insult an enemy one would say, "The flesh of your mother sticks between my teeth." This, Diamond asserts, means the food supply of the people ultimately ran out.[32] Cannibalism, however, was widespread across Polynesian cultures.[33] Human bones have not been found in earth ovens other than those behind the religious platforms, indicating that cannibalism in Easter Island was a ritualistic practice. Contemporary ethnographic research has proven there is scarcely any tangible evidence for widespread cannibalism anywhere and at any time on the island.[34] The first scientific exploration of Easter Island (1914) recorded that the indigenous population strongly rejected allegations that they or their ancestors had been cannibals.[35]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hemm, Robert & Mendez, Marcelo. (2003). Aerial Surveys of Isle De Pasqua: Easter Island and the New Birdmen. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0183-1_12

- ^ "Easter Island". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ Baker, P. E.; Buckley, F.; Holland, J. G. (1974). "Petrology and geochemistry of Easter Island". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 44 (2): 85–100. Bibcode:1974CoMP...44...85B. doi:10.1007/BF00385783. S2CID 140720604.

- ^ Haase, K. M.; Stoffers, P.; Garbe-Schonberg, C. D. (1997). "The Petrogenetic Evolution of Lavas from Easter Island and Neighbouring Seamounts, Near-ridge Hotspot Volcanoes in the SE Pacific". Journal of Petrology. 38 (6): 785. Bibcode:1997JPet...38..785H. doi:10.1093/petroj/38.6.785.

- ^ a b c d e Vezzoli, Luigina; Acocella, Valerio (2009). "Easter Island, SE Pacific: An end-member type of hotspot volcanism". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 121 (5/6): 869–886. Bibcode:2009GSAB..121..869V. doi:10.1130/b26470.1. S2CID 131106438.

- ^ Bandy, Mark (1937). "Geology and Petrology of Easter Island". Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 48 (11): 1599–1602, 1605–1606, Plate 4. Bibcode:1937GSAB...48.1589B. doi:10.1130/GSAB-48-1589.

- ^ Rapanui: Edmunds and Bryan Photograph Collection Archived 3 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Libweb.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ "Enjoy Chile – climate". Enjoy-chile.org. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Easter Island Article Archived 3 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine in Letsgochile.com

- ^ Weather, Easter Island Foundation, archived from the original on 2 October 2009

- ^ "Datos Normales y Promedios Históricos Promedios de 30 años o menos" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "CLIMAT summary for 85469: Isla de Pascua (Chile) – Section 2: Monthly Normals". CLIMAT monthly weather summaries. Ogimet. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Mataveri / Osterinsel (Isla de Pascua) / Chile" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ Mieth, A.; Bork, H. R. (2010). "Humans, climate or introduced rats – which is to blame for the woodland destruction on prehistoric Rapa Nui (Easter Island)?". Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (2): 417. Bibcode:2010JArSc..37..417M. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.10.006.

- ^ Casey, Nicholas (14 March 2018). "Easter Island Is Eroding". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael. (2008). Chilean Wine Palm: Jubaea chilensis Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

- ^ Steadman 2006, pp. 251, 395

- ^ Steadman 2006, pp. 248–252

- ^ Hucke-Gaete R.; Aguayo-Lobo A.; Yancovic-Pakarati S.; Flores M. (2014). "Marine mammals of Easter Island (Rapa Nui) and Salas y Gómez Island (Motu Motiro Hiva), Chile: a review and new records" (PDF). Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 42 (4): 743–751. doi:10.3856/vol42-issue4-fulltext-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2016.

- ^ Acevedo J.; O'Grady M.; Wallis B. (2012). "Sighting of the fin whale in the Eastern Subtropical South Pacific: Potential breeding ground?". Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía. 47 (3): 559–563. doi:10.4067/S0718-19572012000300017. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ "Rapamycin – Introduction". Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ "Rapamycin Extends Longevity in Mice". 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Jones, David T. (2007). "Easter Island, What to learn from the puzzles?". American Diplomacy. Archived from the original on 2007-11-28.

- ^ Diamond 2005, p. 107

- ^ "Easter Island Statues Could Have 'Walked' Into Position". Wired. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ Finney (1994), Hunter Anderson (1998); P.D. Nunn (1999, 2003); Orliac and Orliac (1998)

- ^ Diamond 2005, pp. 79–119.

- ^ Peiser, B. (2005). "From Genocide to Ecocide: The Rape of Rapa Nui" (PDF). Energy & Environment. 16 (3&4): 513–539. Bibcode:2005EnEnv..16..513P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.611.1103. doi:10.1260/0958305054672385. S2CID 155079232. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-10.

- ^ Heyerdahl 1961

- ^ Heyerdahl 1961, p. 57

- ^ Diamond 2005, p. 109

- ^ Kirch, Patrick (2003). "Introduction to Pacific Islands Archaeology". Social Science Computing Laboratory, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Flenley, John; Bahn, Paul G. (2003). The enigmas of Easter Island: island on the edge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 156–157.

- ^ Routledge 1919

Bibliography

edit- Diamond, Jared (2005). Collapse. How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-14-303655-5.

- Heyerdahl, Thor (1961). Thor Heyerdahl; Edwin N. Ferdon Jr. (eds.). The Concept of Rongorongo Among the Historic Population of Easter Island. Stockholm: Forum.

- Routledge, Katherine (1919). The Mystery of Easter Island. The story of an expedition. London. ISBN 978-0-404-14231-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Steadman, David (2006). Extinction and Biogeography in Tropical Pacific Birds. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77142-7.