The Fortezza (Greek: Φορτέτζα, from Italian for "fortress") is the citadel of the city of Rethymno in Crete, Greece. It was built by the Venetians in the 16th century, and was captured by the Ottomans in 1646. By the early 20th century, many houses were built within the citadel. These were demolished after World War II, leaving only a few historic buildings within the Fortezza. Today, the citadel is in good condition and is open to the public.

| Fortezza | |

|---|---|

Φορτέτζα | |

| Rethymno, Crete, Greece | |

View of Rethymno with the Fortezza in the background | |

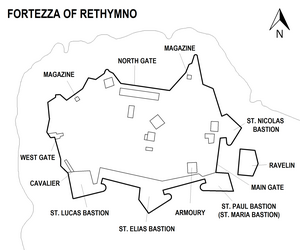

Map of the Fortezza of Rethymno | |

| Coordinates | 35°22′19.2″N 24°28′15.6″E / 35.372000°N 24.471000°E |

| Type | Citadel |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Ministry of Culture and Sports |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Intact |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1573–1580 |

| Built by | Republic of Venice |

| In use | 1580–20th century |

| Materials | Limestone |

| Battles/wars | Cretan War (1645–69) |

History

editBackground

editThe Fortezza is built on a hill called Paleokastro (meaning "Old Castle"), which was the site of ancient Rhithymna's acropolis.[1] Between the 10th and 13th centuries, the Byzantines established a fortified settlement to the east of the hill. It was called Castrum Rethemi, and it had square towers and two gates. The fortifications were repaired by Enrico Pescatore in the beginning of the 13th century. After Crete fell to the Republic of Venice, the settlement became known as the Castel Vecchio or Antico Castello, which both mean "old castle."[2]

Under Venetian rule, a small harbour was built in Rethymno, which became the third most important city on Crete after Heraklion and Chania. On 8 April 1540, a line of fortifications began to be built around the city. The walls were designed by the architect Michele Sanmicheli, and were completed in around 1570. These fortifications were not strong enough to withstand a large assault, and when Uluç Ali Reis attacked in 1571, the Ottomans captured and sacked the city.[2]

Construction and later Venetian rule

editFollowing the fall of Cyprus to the Ottomans in 1571, Crete became the largest remaining Venetian overseas possession. Since Rethymno had been sacked, it was decided that new fortifications needed to be built to protect the city and its harbour. The new fortress, which was built on the Paleokastro hill, was designed by the military engineer Sforza Pallavicini according to the Italian bastioned system.[2]

Construction began on 13 September 1573, and it was complete by 1580. The fortress was built under the master builder Giannis Skordilis, and a total of 107,142 Cretans and 40,205 animals took part in its construction.[2]

Although the original plan had been to demolish the old fortifications of Rethymno and move the inhabitants into the Fortezza, it was too small to house the entire city. The walls along the landward approach to the city were left intact, and the Fortezza became a citadel housing the Venetian administration of the city. It was only to be used by the inhabitants of the city in the case of an Ottoman invasion. Over the years, a number of modifications were made to the fortress. Nonetheless, it was never truly secure as it lacked a ditch and outworks, and the ramparts were rather low.[3]

Ottoman rule and recent history

editOn 29 September 1646, during the Fifth Ottoman–Venetian War, an Ottoman force besieged Rethymno, and the city's population took refuge in the Fortezza. Conditions within the citadel deteriorated, due to disease and a lack of food and ammunition. The Venetians surrendered under favourable terms on 13 November.[4]

The Ottomans did not make any major changes to the Fortezza, except the construction of a ravelin outside the main gate.[5] They also built some houses for the garrison and the city's administration, and they converted the cathedral into a mosque. The fort remained in use until the early 20th century.[2]

By the early 20th century, many residential buildings were located in the Fortezza. Following the end of World War II, the city began to expand and many of the inhabitants moved elsewhere in the city. Rethymno's landward fortifications and many houses within the Fortezza were demolished at this point, but the walls of the Fortezza were left intact. At one point, the local prison was housed within the Fortezza.[2]

Large-scale restoration work has been under way since the early 1990s. The Fortezza is managed by the Ministry of Culture and Sports, and it is open to the public.[5] The Ottoman ravelin now houses the Archaeological Museum of Rethymno.[6]

Layout

editThe Fortezza of Rethymno has an irregular plan, and its walls have a total length of 1,307 m (4,288 ft). The walls contain the following demi-bastions:[1]

- St Nicolas Bastion – the demi-bastion at the east end of the fortress. It contains a Venetian-era building which was possibly originally a storehouse or laboratory.[7]

- St Paul Bastion – the demi-bastion at the southeast end of the fortress. It is also known as Santa Maria Bastion.[8]

- St Elias Bastion – the demi-bastion at the south end of the fortress. It contains the Erofyli open-air theatre, which was opened in 1993.[9]

- St Lucas Bastion – the demi-bastion at the southwest end of the fortress.[10]

The fort's main gate is located on the east side, between St Nicolas and St Paul Bastions.[11] It is protected by an Ottoman-era ravelin, which now serves as the Archaeological Museum of Rethymno.[12] Two smaller gates are located in the west and north sides of the fortress.

A number of buildings are located within the Fortezza, including:

- the Mosque of Sultan Ibrahim, which was formerly the Cathedral of St Nicolas.[13]

- a building near the mosque, which was possibly the Bishop's residence.[14]

- the House of the Rector, which was the residence of the governor of the province of Rethymno. Only its prisons have survived.[15]

- the Council Building, which housed part of the Venetian administration of Rethymno.[16]

- the churches of St Theodore and St Catherine, which were both built in the late 19th century.[17][18]

The fortress also contains an armoury,[19] two gunpowder magazines,[20] storage rooms[21] and several cisterns.[22]

External links

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "The Fortezza fortress". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Kivernitaki, Maria; Samatas, Yannis. "Fortezza in Rethymnon". Explore Crete. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015.

- ^ Valia, Angelaki (2012). "Fortezza Castle". Ministry of Culture and Sport (in Greek). Archived from the original on 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Die Belagerung von Rethymno". rethymnon.gr (in German). Archived from the original on 5 June 2009.

- ^ a b Wass, Stephen. "Rethymno". fortified-places.com. Archived from the original on 19 August 2015.

- ^ "The Archaeological Museum of Rethymno". rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014.

- ^ "The Building at the St. Nicolas Bastion". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Fortezza, the Santa Maria Bastion". Explore Crete. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014.

- ^ "The 'Erofyli' Theatre". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "The Bastion of St. Lucas". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "The Central Gate of the Fortezza Fortress". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "The Archaeological Museum". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "The Mosque of Ibrahim Han". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Episcope Palace". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "The House of the Rector". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "The Council Building". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Holy Temple of St. Theodore of Trihinas". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Fortezza, the church of Agia Ekaterini". Explore Crete. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Armory". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Powder Magazines". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "The complex of the North Gate storage rooms". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Water Tanks". tour.rethymno.gr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.