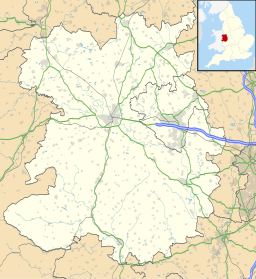

Fenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses National Nature Reserve is a national nature reserve (NNR) which straddles the border between England and Wales, near Whixall and Ellesmere in Shropshire, England and Bettisfield in Wrexham County Borough, Wales. It comprises three peat bogs, Bettisfield Moss, Fenn's Moss and Whixall Moss. With Wem Moss (also an NNR) and Cadney Moss, they are collectively a Site of Special Scientific Interest called The Fenn's, Whixall, Bettisfield, Wem & Cadney Moss Complex and form Britain's third-largest lowland raised bog, covering 2,388 acres (966 ha). The reserve is part of the Midland Meres and Mosses, an Important Plant Area which was declared a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention in 1997. It is also a European Special Area of Conservation.

| Fenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses NNR | |

|---|---|

Part of Whixall Moss | |

| Location | English/Welsh border near Whixall, Shropshire and Bettisfield, Wrexham |

| OS grid | SJ489361 |

| Coordinates | 52°55′N 2°46′W / 52.92°N 2.76°W |

| Area | 2,388 acres (9.66 km2) |

| Created | 1953 (SSSI) |

The mosses form an ombrotrophic raised bog, since the only source of water is from rainfall. Peat is formed when the remains of living plants, particularly Sphagnum, decompose in conditions where there is little oxygen, resulting in layers of peat up to 26 feet (7.9 m) thick in places, although this has been greatly reduced by commercial harvesting of the peat in many areas. In their natural state, such mosses form a dome of peat which can be up to 33 feet (10 m) higher than the surrounding surface, but the domes collapsed as a result of the drainage ditches created to allow harvesting to take place. Three major enclosures of the mosses have taken place, the first as a result of a voluntary agreement signed in 1704, and ratified by the High Court of Chancery in 1710 when opposition prevented the original plans from being carried out. Two Parliamentary enclosures, each authorised by an Act of Parliament were implemented in 1775 on Fenn's Moss and in 1823 on Whixall Moss. Both resulted in common rights being removed and gave the landlords powers which paved the way for the subsequent commercial exploitation of the mosses.

In the early 1800s, the Ellesmere Canal Company built a canal across the southern edge of Whixall Moss. The engineers realised that maintenance would be required, to prevent the formation from sinking into the bog, and a gang of navvies, known as the Whixall Moss Gang, were employed continuously from 1804 to the early 1960s, to keep building up the banks of the canal, now renamed the Llangollen Canal. In the 1960s, the engineering issues were solved, when steel piling was used to underpin this section. The Oswestry, Ellesmere and Whitchurch Railway also planned to cross the mosses, despite being ridiculed by the Great Western Railway for believing that such a thing was possible. They built their line across the north-western edge of Fenn's Moss in 1862, having cut drains in late 1861, and then put layers of heather, wooden faggots and sand on the formation, to allow it to float on the peat. Trains ran from 1862 until the 1960s, without sinking into the mire.

Commercial cutting of peat began in 1851, and a series of six peat works were built over the years, as companies came and went. In order to extract the peat, a network of 2 ft (610 mm) gauge tramways were used, with wagons pulled by horses. The first internal combustion locomotive was bought in 1919, to replace the horses, and three more locomotives were purchased in 1967 and 1968 but did not last long, as the tramway ceased to be used in 1970, to be replaced by Dexta tractors pulling trailers. Mechanised peat cutters were also introduced in 1968. By this time, all of the harvested peat was sold through the retail chain Woolworths, for use in horticulture. The Hanmer Estate, owners of Fenn's Moss, quadrupled the rents in 1989, and the existing operation was bought out by Croxden Horticultural Products. They geared up to extract much larger volumes of peat, to meet the increased rents, but opposition to using peat was increasing, and in late December 1990, the leases were bought by the Nature Conservancy Council, bringing an end to commercial peat cutting. Since then, the mosses have been managed by Natural England and Natural Resources Wales, who have blocked up drainage ditches and removed scrub, allowing water levels to rise, and the ombrotrophic bog to re-establish itself. Circular waymarked trails have been created through some areas of Fenn's and Whixall Mosses, and on Bettisfield Moss, to allow the nature reserve to be appreciated by visitors.

Geography

editFenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses straddle the border between England and Wales. Fenn's Moss is on the Welsh side of the border and is in Wrexham County Borough, while Whixall Moss is in north Shropshire, on the English side of the border, and is only separated from Fenn's Moss by the Border Drain, a ditch similar to many others on the mosses,[1] which was dug in 1826.[2] The former, now dismantled, Oswestry, Ellesmere and Whitchurch Railway line crosses the north-western edge of Fenn's Moss. At the southern edge of Fenn's and Whixall Mosses, the former Ellesmere Canal, now rebranded as the Llangollen Canal, crosses the peat, and Bettisfield Moss lies to the south of the canal, partly in England and partly in Wales. A narrow band of peat connects it to Wem and Cadney Mosses, which again are divided by the Border Drain. Fenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses were declared a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in 1953, with Wem Moss being similarly notified ten years later. The sites were combined and extended in 1994, to become a single SSSI covering 2,388 acres (9.66 km2), of which 1,708 acres (6.91 km2) are in Wrexham and 680 acres (2.75 km2) in Shropshire.[1] Together they form the third-largest lowland raised bog in Britain, with only Thorne Moors and Hatfield Moors in South Yorkshire exceeding them in size.[3] Bettisfield Moss covers 149 acres (60 ha), and includes the largest areas of uncut peat in the whole of the nature reserve, having been little affected by commercial peat cutting.[4]

Two other mosses are part of the same geological Moss complex, though separated from Bettisfield Moss by a strip of agricultural land. Wem Moss in England is a National Nature Reserve which is owned and managed by the Shropshire Wildlife Trust, and is a good example of an uncut lowland raised bog.[5] It covers an area of 70.3 acres (28.4 ha).[6] Cadney Moss is in Wales, and has been largely reclaimed for agriculture and forestry.[7]

Whixall Moss and part of Bettisfield Moss sits above bedrock composed of fine red silt and sand, forming an impermeable layer once known as Upper Keuper Marls. To the north-west of these, the bedrock is composed of Upper Keuper Saliferous Beds, which contain rock salt.[8] Both rock types were re-classified in 2008, and are now part of the Mercia Mudstone Group.[9] As the last ice age receded, the area was covered with glacial moraine, consisting of sands, gravels and clays, in places up to 165 feet (50 m) thick, and this gives the area its characteristic undulating terrain. The shallower depressions filled with peat, and gave rise to the mosses, whereas some of the deeper depressions have remained as open lakes or meres. The depth of peat varies widely over the mosses, from over 26 feet (8 m) in parts of Bettisfield Moss and Fenn's Moss, to around 10 feet (3 m) on parts of Whixall and Fenn's Mosses where commercial peat digging was carried out, and there are some areas where such activity has exposed the underlying rocks.[10]

The mosses are ombrotrophic raised bogs, meaning that they only receive water from rainfall. Such bogs form in areas with an annual rainfall of between 31 and 47 inches (800 and 1,200 mm) which are relatively flat, or which sit over a basin in the underlying rocks, which helps to prevent water run-off. In their natural state, they form domes of peat,[11] which can be up to 33 feet (10 m) higher than the surrounding surface. On the surface are living plants, particularly Sphagnum, which form a crust through which water can permeate relatively easily. Below that, the compacted plant remains are deprived of oxygen, which prevents the usual decay processes, causing them to become peat. Commercial exploitation of the mosses, and their consequent drainage, have resulted in water table levels dropping, and consequently less peat formation.[12]

Fenn's Moss is the source of the Wych Brook, a tributary of the River Dee, which flows northwards from the Moss. The River Roden, a tributary of the River Tern, also rises in the vicinity of Bettisfield and flows southwards to form part of the border between England and Wales near Wem Moss.[13] Near the south-eastern corner of Whixall Moss the never-completed Prees Branch of the Llangollen Canal branches off, to terminate after nearly 1 mile (1.6 km) at a marina, beyond which a little more of the route has become the Prees Branch Canal Nature Reserve Site of Special Scientific Interest.[14]

Occupation

editThere has been human activity on the mosses for millennia, as evidenced by archaeological finds. These include three bog bodies, the first of which was found by peat cutters in c.1867. The body, which was accompanied by a three-legged stool, was that of a young man wearing a leather apron, and was dated to the Iron Age or Romano-British period. The body of a woman from the same period was found in c.1877, and that of a much older Early Bronze Age man was uncovered in 1889. The acidic water and the lack of oxygen resulted in their hair and skin being preserved, while their bones had dissolved. All three were re-buried in local churchyards,[15] the first two at Whitchurch and the third at Whixall, where the remains would have quickly decomposed.[16] In 1927, a Middle Bronze-Age looped palstave, a type of bronze axe, was discovered among remains of a band of pine trees which had crossed the Moss during that period,[17] and can now be seen at the Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery.[18]

There is no documentary evidence for the cutting of peat on the mosses prior to 1572, but it is unclear whether this indicates that it was not general practice, or if there was just no need to burn peat when there was plenty of wood available. Subsequently, a right of turbary, to cut peat for burning was granted to individuals by the Lord of the Manor, and those who were found to be cutting peat but were unlicensed were fined, but the fines were quite modest, suggesting that it was a way of generating income for the Lord of the Manor rather than an attempt to stop the activity. From 1630 it is clear that higher fines were levied on those who sold the peat to people living outside of the manor, while by 1702, peat cutting was more closely regulated, and the levels of fine for unlicensed cutting, or for cutting turves in a neighbour's turf pit, were punitive.[19]

Enclosure

editThe early 18th century saw attempts by the Lord of the Manor to ensure that he had better control of the area and gained some income from the land. In Whixall, Thomas Sandford was the Lord of the Manor, but John, Lord Gower also claimed similar rights for land he held in copyhold. The two men obtained the Statute of Merton and the Statute of Westminster, to allow them to enclose common land in Whixall, including parts of the mosses. The move was supported by around 50 people who held land either as freehold or copyhold, and an agreement was signed on 14 August 1704. The idea was to enclose 600 acres (240 ha) of common land which were sufficiently dry to be usable for agriculture, while the rest of the common land was boggy, and was to be used as a common turbary. The freeholders and copyholders would be granted rights to around two-thirds of the land, with Thomas Sandford and Lord Gower receiving most of the rest, and 20 acres (8.1 ha) being granted to the parson in recognition of his conducting services in Whixall Chapel. In order to lay out the enclosures, six surveyors and mathematicians were employed, but the enterprise was opposed by 23 commoners, who proceeded to destroy existing fencing and prevented new fencing from being erected. The powers contained in the Statute of Merton were totally inadequate for such a situation, and a decree from the High Court of Chancery was obtained on 30 January 1710, to enable further progress to be made. Only 410 acres (170 ha) were actually enclosed, but this included parts of Whixall Moss.[20]

While the enclosure of Whixall Moss was an enclosure by agreement, Fenn's and Bettisfield Mosses were subject to a Parliamentary enclosure, as a result of an Act of Parliament obtained in 1775. Such an act only needed the owners of two-thirds of the land to agree to it and was used by landowners with large holdings to remove the rights of commoners. The major landowner, in this case, was the lawyer and politician Sir Walden Hanmer, and the act added the mosses to the parish of Hanmer. At the time, acts of enclosure were very common in England, but this was only the fourth to be enacted in Wales. Walden Hanmer appears to have been more interested in cultivating the wastes of the parish than in exploiting the peat on the mosses, but the act created 111 strips of land to be used as turbaries, of which Hanmer himself was awarded 56, two were given to the poor in Bronington, one to the school and almshouses in Whitchurch, and the rest shared out between 31 individuals. A similar act was obtained in 1823, which extinguished common rights on Whixall Moss and the English part of Bettisfield Moss. The act defined a number of public drains, which would carry water away from the moss, and as each was named, the act was probably recognising what was already there, rather than creating a new system.[21]

The effects of the enclosures can still be seen, in the pattern of the fields that surround the northern and southern edges of the mosses, in the network of drains that carry water away from the mosses, and in the alignment of roads, tracks and footpaths that still provide access to them. The enclosures resulted in most of Fenn's Moss being under the control of the Hanmer Estate and paved the way for the later commercial exploitation of the peat. On Whixall Moss, the result was that much of the southern part of the Moss was organised into a patchwork of small enclosures, and a much smaller proportion was under the direct control of the Lord of the Manor. Many of these small enclosures have since become pasture or woodland, although some remain as a source of peat turves for their owners.[22]

Transport links

editA decision that would affect the mosses was made in 1797, when the Ellesmere Canal company abandoned plans for a heavily engineered route to join the two halves of their system, which would have linked Trevor Basin to Chester, via Ruabon and Brymbo,[23] and decided instead to build a canal from Frankton Junction to Hurleston Junction, which was completed in 1805.[24] The engineers William Jessop and Thomas Telford decided against building a bypass around the mosses and instead elected to cut straight across the peat, despite the technical difficulties that this posed. They lowered the water table in the moss by building drainage ditches and then constructed a raft, on which the canal floated.[25] They understood that regular maintenance of this section would be a requirement for many years, and a team of navvies, later named the Whixall Moss Gang, were employed to extract clay from a pit on the Prees Branch.[26] The clay was used to build up the banks, and the gang were employed continuously from 1804 until the 1960s on this task.[27] Finally the engineering issues that created the work were solved, and the canal was underpinned with steel piling in the 1960s, to isolate it from the peat.[25] The idea that the drains defined in the 1823 Enclosure Act already existed is confirmed by the fact that they were carried under the canal in culverts when the canal was built across the edge of Whixall Moss in c.1801.[28]

When railways arrived in the area, they also faced the decision of whether to cross the moss or bypass it. The main proposal was for the Oswestry, Ellesmere and Whitchurch Railway, the plans for which were opposed by some local landowners, and also by the Great Western Railway, who were keen to stifle any competition. The opposition resulted in a Parliamentary enquiry into the proposals, which generated a disproportionate volume of documentation for such a small scheme.[29] Although Sir John Hanmer had given permission for the railway to pass around the edge of the moss, their consulting engineer, Benjamin Piercy, thought it was a waste of property not to cross the moss. The railway employed Messrs Brun Lees, engineers, to argue their case, who had previously worked on railways in Brazil. The Great Western Railway argued that the moss consisted of 3 feet (0.9 m) of relatively solid crust, under which there were up to 36 feet (11 m) of liquid peat, and that the cost of crossing the moss had been underestimated by some £23,000. In reply, the consulting engineer G. W. Hemans stated that the cost of the whole moss section would be under £3,000, as he had built railways across bogs in Ireland at a cost of less than £800 per mile. He also produced a solid block of peat, to show that it was not a liquid. The Parliamentary committee narrowly found in favour of the Oswestry, Ellesmere and Whitchurch scheme, although the House of Lords only sanctioned construction of the section from Ellesmere to Whitchurch, including the crossing of Fenn's Moss, and the Oswestry to Ellesmere section was postponed.[30]

Work started on 29 August 1861, with a "programme of rejoicings" to celebrate the event. Even the inmates of the Ellesmere workhouse were included, when they were treated to roast beef and plum pudding the following day. The task of crossing Fenn's Moss started in mid-September, and the progress was recorded by the Oswestry Advertiser and Montgomeryshire Mercury in graphic terms. They reported: "...our ears are assailed with tidings of the maddest of all mad acts on the part of the maddest of madmen! Messrs Savin and Ward, the contractors, who won't believe they are going to ruin although the Great Western Railway Times has over and over again proved the fact to the satisfaction of all reasonable men, have actually commenced crossing Whixall Moss."[31] The contractors cut a series of drains, which allowed the peat to dry and become firmer. After leaving the formation over the winter to settle, heather was spread on the top, followed by a layer of wooden faggots, cut from local woods, and then a thick layer of sand, obtained from banks within the moss. By 27 February 1862, the railway was able to run a locomotive and carriages across the Moss, to help in consolidating the formation, and goods services started on 20 April 1863, with passenger trains following shortly afterward, on 4 May. In 1864, the company merged with others to form the Cambrian Railways Company, and in 1922, the Cambrian merged with the Great Western Railway, giving them control of the line they had tried so hard to scupper.[32]

Peat extraction

editThe various enclosures acts, with the consequent removal of common rights and the vesting of control in the landowners, paved the way for subsequent commercial extraction of the peat on the mosses.[28] This began in 1851, when a "company of gentlemen", named Vardy & Co., leased 308 acres (125 ha) from the Hanmer Estate. They intended to erect a works, where useful products would be manufactured from the peat. On 5 May 1856, Joseph Bebb took over the lease, to which was added another 300 acres (120 ha), for a period of 21 years. From his Old Moss Works, Bebb built a tramway eastwards to the canal, where there is a raised area of towpath and a simple wharf. No records of levels of production have survived, but on 12 September 1859, the lease was taken over by Richard Henry Holland, and on 3 August 1860 passed to The Moulded Peat Charcoal Company Limited, a company of which Holland was a director.[33] They bought the patent for a machine to turn peat into moulded briquettes, which could be burnt or converted into charcoal or coke. The process was not new to the moss, as records show that moulded peat blocks were being produced as early as 1810. The new company did not last and ceased trading on 12 December 1864.[34]

By 1884, George Wardle occupied Fenn's Hall, and started a moss litter business, producing peat for animal bedding. Two years later he was joined in the venture by William Henry Smith, an ironfounder from Whitchurch, and they set up The English Peat Moss Litter Company, which they formally registered on 12 May 1888. They leased land on the north-eastern part of Fenn's Moss from the Hanmer Estate, and in 1889, they obtained rights to the centre of Whixall Moss, by buying the Lordship of the Manor from William Orme Foster. This came with the obligation to maintain the drains, under the terms of the 1823 Enclosure Act, an issue that caused numerous disputes over the years. The company extracted peat from Fenn's Moss, and Wardle and Smith rented out parts of Whixall Moss to local turf cutters.[35] They built the Old Shed Yard Works, a little to the north of the Old Moss Works, and used horse-drawn tramways to transport the finished product away from the works. On the moss, tracks went to the north-west, turned to the south-west and then to the south-east, to reach Oaf's Orchard, on the border between England and Wales. From the works, another tramway headed northwards to Fenn's Bank Brick and Tile Works, where there was an interchange siding with the Cambrian Railway.[36]

From 1889, the English Peat Moss Litter Company started to build houses for its workers, using materials obtained from the Fenn's Bank Brick and Tile Company and had completed 17 dwellings by 1898. At some point, probably before 1914, William Smith sold his share of the company to George Wardle. Wardle employed around 50 people, but in 1914 there was industrial unrest, including threats to those who chose to keep working, and the works closed intermittently until the dispute was resolved.[37] During World War I, the War Department commandeered much of Fenn's and Whixall Mosses, for use as rifle ranges, but continued to cut peat, which was used for bedding at a cavalry remount station located at Bettisfield Park. It appears that Wardle surrendered his lease to the authorities at this time and that Tom Allmark, the works foreman, worked for the military, producing peat. They established a peat works, known locally at the Old Graveyard, near to Bettisfield Moss and the railway line. They clearly used tramways, since an auction sale of the works after the war ended included 2,874 yards (2,628 m) of Decauville railway track and 103 assorted wagons.[38]

It appears that the Old Graveyard Works was bought by a speculative company called The Bettisfield Trust Company. They obtained a lease from the Hanmer Estate in 1923, allowing them to work 948 acres (384 ha) for black peat, which was peat at the lower levels of the bog. The Midland Moss Litter Company also obtained a lease for the same area, but they wanted to harvest the upper layers for packing material, cattle feed, and animal bedding. The two companies were required to cooperate under the terms of the lease. William Henry Smith, the former partner of Wardle, was a director of the Bettisfield Trust,[39] but details of exactly what they did are unclear, and they may have established a processing works for making briquettes and distillation of the peat in the Fenn's Bank Brick and Tile Works, rather than at the Old Graveyard site. The enterprise was fairly short-lived, as they ceased trading in late 1925.[40]

The Midland Moss Litter Company established a new works a little further along the railway line, although for a while both works were in operation. They introduced new working practices to the Moss, based on Dutch methods, and rebuilt the Fenn's Old Works in 1938 when the previous one was destroyed by fire. They introduced locomotives to the tramways in 1919, although the peat turves were always cut by hand, and of all the companies operating on the mosses, survived the longest. They continued working on the Moss until August 1962, but almost no documentary evidence for them is known to exist.[41] The company was liquidated during a period when the demand for peat generally was in decline, and the site was bought by L S Beckett.[42] Len Beckett had operated a small peat-cutting business, using Manor House, which his father had bought in 1933, as a base. He died young, and the business was bought by his brother-in-law, Tom Allmark, who could see the potential for peat in horticulture. In 1956 he bought 205 acres (83 ha) of Whixall Moss from Wardle, bought Manor House in 1957, and soon afterward, obtained a contract to sell peat to Cuthberts of Llangollen, which was sold as bulb fibre through the retail chain Woolworths. Tom's son Herb Allmark took over running the company in May 1960, and the business expanded when he obtained the Fenn's Old Works and the lease on Fenn's Moss from the Midland Moss Litter Company in 1962.[43]

Beckett's bought the western half of the English part of Bettisfield Moss in 1956 and the Welsh part of it in 1960. The English part was overgrown, but the Welsh part was free of trees, as it had been regularly cleared by burning, and by some domestic peat cutting. They experimented with harvesting the western part of the Welsh Moss commercially in the 1960s, but difficulties with transporting the cut peat to their processing works at Whixall meant that the project was short-lived. Subsequently, pine seedlings colonised the Moss, which Beckett's sold as Christmas trees during the 1960s, but when they stopped doing so, the Moss was rapidly overgrown. The eastern half of the English Moss had been bought by the Darlington family in the late 1800s and was for a time rented out to Humus Products Ltd, who cut peat.[44]

By the mid-1960s, all of the peat produced was sold to Woolworths, but the costs of transport from Fenn's Old Works to Manor House rose, so Allmark extended the tramways on the Moss, and purchased three more secondhand locomotives to supplement the one bought in 1919. He introduced mechanised peat cutters to the Moss in 1968, and in the early 1970s, some of the machinery was moved from Fenn's Old Works to Manor House.[45] When the Hanmer Estate quadrupled the rents in May 1989, L S Beckett sold its operation to Croxden Horticultural Products. L S Beckett had extracted some 26,000 cubic yards (20,000 m3) of peat in the final year of operation, but to make a profit, Croxden's would need to extract much bigger volumes. They rebuilt Manor House Works, and by December 1990 were ready to extract more than double that amount per year. However, the lobby against using peat was growing rapidly, and the Nature Conservancy Council bought the leases, bringing commercial extraction of peat on the Mosses to an end. For many of the men for whom working on the mosses was a way of life, the demise of their industry was greeted with great sadness.[46]

Locomotives

edit| Builder | Type | Built | Works number | Notes (Details from Berry 1996, pp. 108–109) | Status (2012) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Rail | 4w 20 hp | 1919 | 1934 | Bought new, with petrol engine. | Derelict at Whixall.[47] |

| Motor Rail | 4w 20 hp | 1926 | 4023 | Secondhand. Rebuilt at Whixall and fitted with 22 hp Armstrong Siddeley diesel engine 1967. | Stored at private location in Hampshire.[48] |

| Ruston and Hornsby | 4w | 1934 | 171901 | Bought Spring 1968 from Dowlow Lime and Stone Co, Derbyshire. Regauged from 2 ft 3 in (686 mm) gauge. | At Lime Kiln Wharfe Industrial Railway, Stone, Staffs.[49] |

| Ruston and Hornsby | 4w 11/13 hp | 1938 | 191679 | Fitted with an air-cooled Lister diesel engine in c.1966. Bought September 1968 from Nash Rocks Stone and Lime Co, Radnor. | Derelict at Whixall.[47] |

The tramways on the Mosses were all 2 ft (610 mm) gauge. The wagons were manufactured locally, and could be used as flat-bed trucks, when transporting peat bales, or could be fitted with slatted wooden sides, when carrying cut peat blocks. The main tracks were fixed to wooden sleepers with flanged iron nails. When dried peat was ready for removal from the Mosses, temporary lines were laid by inserting a point into the main line, and building a siding using rails permanently fixed to metal sleepers. The railway ceased to be used in 1970, after which peat was removed from the moss in trailers towed by Dexta tractors.[50]

Regeneration

editFenn's and Whixall Mosses have been recognised as a Site of Special Scientific Interest since 1953, and attempts were made to buy the land worked by L S Beckett for nature conservation, but no agreement was reached. When Croxden Horticultural Products took over, there were discussions between them and the Nature Conservancy Council, to see whether some areas of the mosses could be restored. In December 1990, all of their leases and land were bought by the Nature Conservancy Council, and large-scale commercial peat-cutting ended immediately.[51] Local opposition to commercial extraction of peat had been spearheaded by the Fenn's and Whixall Mosses Campaign Group, a grouping of around 20 local organisations, with the Shropshire and North Wales Wildlife Trusts taking the major role. The Nature Conservancy Council obtained the lease for 640 acres (260 ha) of Fenn's Moss, and bought 170 acres (70 ha) on Whixall Moss and a further 112 acres (45.3 ha) on Bettisfield Moss. Subsequently, the Countryside Council for Wales have obtained leases to another 363 acres (147 ha) of Fenn's Moss, and English Nature have bought 55 acres (22.3 ha) of Whixall Moss.[52]

English Nature was able to employ some of the peat workers, to assist in the regeneration of the mosses, and their specialist knowledge of the network of drains and how to operate machinery on the fragile landscape has proved invaluable. They were also able to buy vehicles from Croxden Horticultural Products, including a 12-tonne Bigtrack bogmaster dumper, a 4 tonne tracked Smalley excavator, a Backer screw-leveller, and two old Dexta tractors with Moss trailers.[53] The mosses contain areas which have never been cut, areas which have been cut by hand, and areas where commercial cutting has taken place. Each presents its own problems, but as a result of the drainage, all are affected by invasive trees and scrub which is normally associated with heath lands, particularly pine trees on Bettisfield Moss and birch scrub elsewhere.[54]

English Nature worked on a management plan for the mosses, which was published in 1993 as the Synopsis Management Plan. It contained eleven objectives, designed to protect the area[55] and ultimately to re-establish it as a raised bog. There has been an extensive programme to clear the birch scrub, which has often been dumped into the drains, to raise water levels, and by mid-1995, dams had been constructed across all of the drains, to retain water on the mosses. Pine trees can be chipped, but birch is more problematic, and where it is extensive, it has been burnt on large metal plates, and the ash removed to prevent enrichment of the peat.[56] Where leakage of water containing high levels of nutrients has occurred, giving rise to alder and willow carr populations, such sources have been traced. The Llangollen Canal was isolated from the mosses by deep piling, carried out by British Waterways in the early 1990s, to prevent leakage from the canal, and a spring on Fenn's Moss, which carried high concentrations of nutrients, has been dammed. The retention of rain water on the mosses has been very successful, and mire vegetation is gradually re-establishing itself.[57]

The Welsh part and the western half of the English part of Bettisfield Moss was sold to Natural England and Natural Resources Wales in 1990. The eastern part of the English Moss had been bought by a Mr Wilcox in 1978, and was sold to Natural England in 1998. Most of the Moss was a dense pine forest, but Natural England bought the car park at World's End, and this hard area allowed the pine forest to be cleared in 2001, as the wood could be stacked on it until it was transported away. Some oak and birch woodland around the edge of the Moss was kept at the request of local people, for cosmetic reasons.[44] Ditches around the edge of the Moss have been dammed, to encourage the growth of marginal plants, such as purple marsh thistle, yellow great bird's-foot trefoil, meadowsweet and soft rush.[58]

The importance of the mosses as a scarce habitat has been recognised, and as well as being a Site of Special Scientific Interest and a National Nature Reserve, it is now part of the Midland Meres and Mosses Ramsar site, a designation that recognises internationally important wetlands. Some of the restoration of the mosses has been funded by grants from the Heritage Lottery Fund.[59] Together with Wem and Cadney Mosses, it is also a European Special Area of Conservation. Among the primary reasons for the designation of the site are the presence of three types of sphagnum, all three British types of sundew, cranberry, bog asphodel, royal fern, white beak-sedge and bog-rosemary. It is one of the few places where the moss Dicranum affine can be found, and provides habitat for over 1,700 species of invertebrates, including 29 which are rare in Britain.[60] Following restoration, the mosses have become wetter, and this has allowed populations of curlews and mallards to expand, while in winter, there are breeding populations of teal and shoveler. The increased numbers of small birds have also resulted in the numbers of predatory peregrine falcons increasing. Raft spiders abound near the peaty pools, and 28 species of dragonfly have been recorded on the mosses.[2]

In October 2016 Natural England obtained £5 million to allow further regeneration work to be undertaken. The grant will be spread over five years and will enable Natural England, working with Natural Resources Wales and the Shropshire Wildlife Trust, to buy another 156 acres (63 ha) of peatland and to raise the water levels over some 1,480 acres (600 ha) of the mosses, using new techniques, such as contour bunding, to achieve this. There are also plans to restore other types of habitat around the edges of the mosses, including swamp, fen, and willow and alder carr wet woodland. This will assist populations of willow tit and marsh tit, and encourage the growth of rare bog species such as elongated sedge and several varieties of micro-moths. The money will also fund the diversion of 2.8 miles (4.5 km) of ditches containing mineral-rich water, and assist in the clean-up of Whixall Moss scrapyard, which was bought by the Shropshire Wildlife Trust as the site for a new visitor centre but was contaminated with engine oil and 100,000 used vehicle tyres.[61]

In 2001 a partnership between English Nature, the Countryside Council for Wales and British Waterways (since succeeded by Natural England, Natural Resources Wales and the Canal and River Trust respectively), developed circular waymarked trails through some areas of Fenn's and Whixall Mosses. Wildlife in the nature reserve includes kingfisher, mute swans, watervoles, damselfly and dragonfly species such as the white-faced darter, various species of duck, and even the rare bird of prey the hobby. Plants include cotton sedge, bog moss (Sphagnum), great hairy willowherb, bog myrtle, water figwort, flag iris, cross-leaved heath, bog rosemary, cranberry and sundew; common alder trees, alder buckthorn, grey sallow and crack willow predominate in wooded fringes, along with some introduced scotch pine.

See also

editBibliography

edit- Berry, A Q; et al. (1996). Fenn's and Whixall Mosses. Wrexham County Borough Council. ISBN 978-1-85991-023-8.

- Grant, M.E. (1995). The dating and significance of pinus sylvestris l. macrofossil remains from Whixall Moss, Shropshire: palaeoecological and modern comparative analyses. Ph.D., Keele University (United Kingdom) EThOS uk.bl.ethos.262380

- Guide (2010). Fenn's, Whixall & Bettisfield Mosses National Nature Reserve (PDF). Natural England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Hadfield, Charles (1985). The Canals of the West Midlands. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8644-6.

- Handbook (2012). Industrial Locomotives (16EL). Industrial Railway Society. ISBN 978-1-901556-78-0.

- Horton, K. (2008). The effects of rehabilitation management on the vegetation of Fenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses national nature reserve: a cut-over lowland raised mire. Ph.D. University of Wolverhampton (United Kingdom). EThOS uk.bl.ethos.532817

- Nicholson (2006). Nicholson Guides Vol 4: Four Counties and the Welsh Canals. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-721112-8.

- Trail (2013). "Bettisfield Moss Trail". Natural England. ISBN 978-1-78367-018-5.

- Trail (August 2014). "Fenn's & Whixall Mosses History Trail". Natural England. ISBN 978-1-78367-019-2.

References

edit- ^ a b Berry 1996, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Guide 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 7.

- ^ Trail 2013, p. 2.

- ^ "Wem Moss". Natural England. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "Wem Moss". Shropshire Wildlife Trust. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ "Cadney Moss (400818)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 8.

- ^ "The BGS Lexicon of Named Rock Units". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 2–3.

- ^ "Roden - source to conf unnamed trib". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Nicholson 2006, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Trail 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 43.

- ^ Trail 2014, p. 10.

- ^ "Bronze Age looped, ribbed palstave". Darwin Country. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, p. 174.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, p. 178.

- ^ a b "Early History of the Shropshire Union Canals". Shropshire Union Canal Society. Archived from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "The Whixall Moss Gang (2)". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales / BBC. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "The Whixall Moss Gang (3)". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales / BBC. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ a b Berry 1996, p. 53.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 57.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 60.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 90.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 99.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 101–102.

- ^ a b Trail 2013, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b Handbook 2012, p. 177.

- ^ Handbook 2012, p. 97.

- ^ Handbook 2012, p. 194.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 109.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 104.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 121.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 126.

- ^ Berry 1996, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Berry 1996, p. 133.

- ^ Trail 2013, p. 5.

- ^ "Implementation of the Ramsar Convention" (PDF). Department of the Environment. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "Fenn`s, Whixall, Bettisfield, Wem and Cadney Mosses". JNCC. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "£5million windfall for Marches Mosses". Shropshire Wildlife Trust. 11 October 2016. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

External links

editMedia related to Fenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses NNR at Wikimedia Commons

- Photographs of Whixall Moss and surrounding area & Fenns Moss from the Geograph project

- Fenn’s, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses from Natural England's Corporate report, Shropshire's National Nature Reserves.