Christ Church, Washington Parish

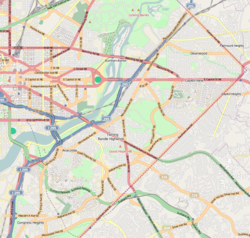

Christ Church — known also as Christ Church, Washington Parish or Christ Church on Capitol Hill — is a historic Episcopal church located at 620 G Street SE in Washington, D.C., USA.[3] The church is also called Christ Church, Navy Yard, because of its proximity to the Washington Navy Yard and the nearby U.S. Marine Barracks.

Christ Church | |

Christ Church, Washington Parish | |

| Location | 620 G Street, S.E. Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°52′53″N 76°59′52″W / 38.88139°N 76.99778°W |

| Built | 1807 |

| Architect | Robert Alexander (1781-1811) (misattributed to Benjamin Henry Latrobe)[2] |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 69000291[1] |

| Added to NRHP | May 25, 1969 |

Christ Church was established in 1795, one of two congregations envisioned for Washington Parish, created by an act of the Maryland General Assembly in 1794. Initially, worship services were held in a converted tobacco barn. The present structure was built in 1807, the first Episcopal church in the original city of Washington, on land given by William Prout. Through changes to its exterior and interior over the years, the building has been the site of a continuously worshiping community ever since. The church was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969. The Rev. John A. Kellogg is the current rector.

History

editFounding of the Parish, 1794

editWhen the District of Columbia was created, there was no Episcopal Church in the city of Washington or Georgetown,[nb 1] although there had been an Episcopal presence. The Church of England had bought land for building an Anglican church in Georgetown in 1769. The Revolutionary War and time needed to establish the new Episcopal Church delayed building, but Anglican services were sometimes held at the Georgetown Presbyterian Church on Bridge St. (now M St.).[5] Services connected to St. John's Broad Creek were held in a renovated tobacco barn on Capitol Hill, possibly as early as the 1780s.[6]

Nevertheless, existing Episcopal churches were miles from where population growth was expected, and the Rt. Rev. Thomas Claggett, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland and first Episcopal bishop consecrated in the United States, was determined that there should be an Episcopal church in the nation's capital. In 1793, he appointed prominent local businessmen and landed gentry to explore using a lottery to finance building a church there. After that group, including Samuel Blodgett, Uriah Forrest, Benjamin Stoddert, William Deakins, and Anthony Addison, failed to make progress,[7] the bishop pressed on to the Maryland legislature. The Maryland Vestry Act of 1794, drawing boundaries for a new parish in the Diocese of Maryland, made up of Washington and Georgetown, was signed into law on December 26, 1794.[8]

Early Years, 1795-1844

editThe first meeting establishing Christ Church was held on May 25, 1795. Although Bishop Claggett had voiced his desire to be rector[9] the newly elected vestry called the Rev. George Ralph, who had recently moved from Maryland to start a school in Washington.[10] Many clergy—often the best educated men in the community—ran schools to supplement incomes that otherwise came solely from pew fees.[11] The first vestry, prominent local land owners, speculators, businessmen, and local politicians William Deakins, Jr., John Templeman, Charles Worthington, James Simmons, Joseph Clarke, Thomas Johnson, Jr., and Gustavus Scott, appointed Henry Edwards as registrar, and elected Clotworthy Stevenson and William Prentiss as wardens for one year. In the following year, Thomas Law, General Davidson, and John Crocker were appointed to take the places of Johnson, Clarke, and Simmons, who had left the parish.[12]

Few parish records of this first decade survive, but other sources document that worship services were held in the converted tobacco barn and in the hallway of the War Office on Sunday afternoons.[13] When Ralph left after two years to return to Maryland, his assistant, the Rev. Andrew McCormick was left in charge.[10][7] In 1807, Ralph, still nominally the rector, returned to the city and called a parish meeting. Although in the interim the parish may have been, like the city, as much vision as reality,[14][15] the meeting resulted in the election of a new vestry: Commodore Thomas Tingey, John Dempsie, Bullveer Cocke, Andrew Way, Thomas H. Gillis, Thomas Washington, Peter Miller, Robert Alexander, and Henry Ingle. Ralph resigned, and the new vestry elected McCormick as rector.[nb 2] It is in 1806, shortly before Ralph's return that vestry minutes begin anew and continue to the present time.[16]

During McCormick's tenure the new church was built on land donated by William Prout, a land owner, developer, businessman, and civic leader in the new city.[17] The church was completed in 1807 and dedicated in 1809 by Bishop Claggett. In 1812, the vestry of Christ Church took ownership of a cemetery that had been established in 1807 by men who were also members of Christ Church: George Blagden, Griffith Coombe, John T. Frost, Henry Ingle, Dr. Frederick May, Peter Miller, Samuel Smallwood, and Commodore Tingey.[18] This Washington Parish Burial Ground quickly became known as Congressional Cemetery.[19]

During the War of 1812, the community around the church survived the burning of the Washington Navy Yard, just blocks away. The fire was started by Mordecai Booth, another Christ Church vestryman, under orders of Tingey, Commander of the Navy Yard, to prevent the British from capturing a valuable foothold in the nation's capital.[20] Archibald Henderson, longest serving Commandant of the Marine Corps, also played a prominent role in the life of the church and served on its vestry.[21] As the communities around the Capitol and the Navy Yard grew, so did Christ Church, expanding its physical structure in the first of many renovations in 1824.[22] Likewise, the city of Washington was growing. The boundaries of Washington Parish, which had encompassed the original City of Washington and Georgetown, began to contract as new churches formed and parish boundaries were set for them:[nb 3] St. John's Georgetown in 1809,[24] St. John's Lafayette Square in 1816, Trinity Church in 1827 (demolished 1936), Epiphany in 1844, and Ascension in 1845.[7]

The Civil War Era, 1844-1870

editThe Episcopal Church as a whole and the Diocese of Maryland were not particularly progressive on the issue of slavery.[25][26] A number of early Christ Church leaders were enslavers.[27] While both free and enslaved African Americans appear to have been baptized, confirmed, and married at and communicants of Christ Church from at least 1805, their numbers were few and seating was segregated, with one of the balconies reserved for enslaved persons.[nb 4] Christ Church allowed African Americans to be buried in its cemetery but not in the original enclosed portion of the burial ground.[28] Before the war, Christ Church called an anti-slavery rector in the Rev. Julius Morsell[16] and after the war, a southern sympathizer in the Rev. Charles Hansford Shield. In 1858 Christ Church hired Theophilus Howard, an African American, as sexton.[29] During the war Union forces used its tower to observe the area across the Potomac.[16] In 1865 it counted among its members David Herold, one of the Lincoln assassination co-conspirators. A member of the parish, Dr. Samuel McKim, spoke in Herold's defense at his trial, and the rector of the parish, the Rev. Marcus Olds, was at the scaffold with Herold, as were other clergy with the other co-conspirators.[16][30] Except for expressed relief that the church building was not commandeered for the war efforts and an authorization to drape the bell tower in black after Lincoln's assassination, there is little mention of the issue of slavery or the effects of war in the vestry proceedings of the time.[16]

The Gilded Age, 1870-1900

editIf hard use during the war battered Capitol Hill's roads and existing buildings, it also brought new residences, schools and military and civic buildings, and the local population grew after the 1883 Pendelton Civil Service Reform Act gave federal workers greater job security and regular wages.[31] Christ Church mirrored this pattern, growing from 147 communicants in 1870 to 532 in 1895.[32][33]

The best known Christ Church member is John Philip Sousa, the famous March King and head of the Marine Corps Band from 1880-1892. He was born at 636 G St., SE, just three doors east of Christ Church and had a lifelong association with the parish.[34] Sousa referred to Christ Church in a novel he wrote set in the Pipetown neighborhood east of the Marine Barracks.[35] Christ Church was stable enough to establish a parochial chapel, St. Matthew's, at Half and M Streets, SE, in 1892. St. Matthew's added a parish hall in 1914.[36][37] During this time Christ Church was known for its music program. A Hook & Hastings organ was installed in 1880, and there were a boys' choir and sponsored musical events.[38] The church celebrated its centennial on May 25, 1895.[36] That year saw the establishment of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, which split the District of Columbia and nearby Maryland counties from the Diocese of Maryland. The end of the 19th century gave the church the dubious distinction that former rector the Rev. Gilbert Fearing Williams was the first clergyman in the newly formed Diocese of Washington to be tried for misconduct. Having been found guilty, Williams was deposed by Bishop Satterlee in 1898, but was reinstated in 1914 by Bishop Harding when new evidence came to light.[39][40]

World Wars, 1900-1946

editThe neighborhood was relatively stable during the first half of the 20th century, even during the Depression, in part on the strength of federal government employment, particularly in the Navy Yard.[41][42] Parish leadership similarly saw stability, with the Rev. Arthur Shaaf Johns beginning his 20-year service as rector in 1897. Johns, son of the Rt. Rev. John Johns, Bishop of Virginia, was also a Confederate veteran.[43] In 1903, Christ Church built a chapel at Congressional Cemetery. During World War I, while the Rev. David Covell was rector, the church hosted dinners for armed service members.[44][45][46] In the 1920s, the church had the resources to undertake a major interior redesign, changing the look from heavy Victorian ornamentation to imitation stone, more in keeping with the neo-Gothic appearance of the exterior.[47] The longest-serving rector after Johns was the Rev. Edward Gabler, whose tenure reached 18 years.[48][49] In 1930 parish by-laws were changed so that women members of the congregation could vote in parish elections.[50] Gabler assisted at the funeral of John Philip Sousa in 1932.[51] In 1938 the church purchased a Hammond electric organ with a full accompaniment of chimes that Gabler loved to play.[52] When Gabler left, the congregation had remained relatively stable in size for 50 years,[53][54] but the neighborhood was starting to show signs of stress and disrepair.[55][56]

Decline and Revitalization, 1947-1983

editIn the 1950s, during the terms of the Revs. John H. Stipe and Ivan E. Merrick, Jr., the alley dwellings behind the church were cleared, replaced by a parking lot and playground, and the church building underwent a major renovation.[57][58] Historic preservation efforts also began to shape the Capitol Hill neighborhood around the church.[59] In the wake of the 1954 Supreme Court decision desegregating D.C. public schools (Bolling v. Sharpe), racial demographic shifts across the city accelerated,[60] and the Rev. Donald A. Seaton, called as rector in 1965, advocated efforts to attract young people and foster racial integration. However, the pace and nature of his changes provoked some members of the congregation, and Seaton resigned by 1968.[61][62]

Despite the parish's diminished membership and resources, efforts to connect with the Capitol Hill community, begun by Seaton and continued by the rectors who followed, resulted in Christ Church's support for the founding of a day school, a social services agency, and a community arts organization. The parish day school begun in the early 1960s, joined with the Lutheran Church of the Reformation to eventually become the Capitol Hill Day School. It was led by Bessie Wood Cramer, the parish's first female vestry member, who had been responsible for managing D.C. public school desegregation in the 1950s.[63][64] Christ Church participated in the establishment of Capitol Hill Group Ministry, a coalition of Capitol Hill churches responding to the racial tensions and social needs of an increasingly diverse Capitol Hill population. Capitol Hill Group Ministry incorporated as a 504(c)(3) nonprofit provider of social services in 1967,[65] and today is known as Everyone Home DC, a community provider of services to prevent and ameliorate homelessness.[66] Capitol Hill Arts Workshop began a long relationship with Christ Church in 1972, holding many classes and staging shows in the parish hall until it secured dedicated space at 7th and G Streets, SE, in the early 1980s.[16][67]

On May 25, 1969, the Rev. David Dunning presided over the church's 175th anniversary celebration. The U.S. Marine Band presented a concert on the lawn, G Street was closed to traffic, and an Interior Department official added Christ Church to the National Register of Historic Places.[68][69] Picketers stood just outside the church fence, protesting the presence of General William Westmoreland, a commander of American forces in Vietnam, who had been invited along with other dignitaries.[16]

After the Episcopal Church approved the ordination of women to the priesthood in 1976, the Rev. Carole A. Crumley, ordained at Washington National Cathedral in January 1977, was called as the parish's first female priest, serving as assistant rector and as interim rector during 1977-1979.[70]

1985-Present

editIn the mid-1980s, the parish was active in the AIDS crisis, hosting educational sessions for the parish and the community and raising funds. The church helped establish the Diocesan program, Episcopal Caring Response to AIDS (ECRA), and with other Diocesan churches, it sponsored a group home for individuals with AIDS, staffed by the Whitman-Walker clinic.[71]

Christ Church celebrated its bicentennial in 1994 with the Rev. Robert Tate as rector.[72][73] The Rev. Judith Davis, the church's first female rector, followed Tate in 1996.[16] While the Rev. Cara Spaccarelli was rector (2009-2018),[74] solar panels were installed on the parish hall roof, the parish hall was renovated, and a new organ was installed, Opus 3914 of Casavant Frères. Built expressly for the worship space, the organ replaced an instrument in place since 1972, which was a composite based on a 1901 Hook & Hastings organ purchased from St. Cyprian's Roman Catholic Church.[75] Spaccarelli was a Capitol Hill Community Achievement Award honoree in 2018.[76] During the COVID-19 pandemic, the church called the Rev. John Kellogg as its 29th rector.[77]

Architecture

editConstruction

edit- April 7, 1806 The vestry named Robert Alexander ("a builder architect in the 18th century tradition"[78]) to prepare a plan and estimate for building Christ Church.[79]

- May 5, 1806 The vestry appointed a committee of Comm. Tingey, John Dempsie, and Peter Miller to "seek a lot from William Prout...one of the few proprietors to remain solvent throughout the development of early Washington."[79][80]

- "George Blagden, the Capitol's stonemason, and Griffith Coombe, Capitol Hill's most successful building contractor, examined several drawings and estimates before settling on the design submitted by Alexander; it was approved by the vestry on June 16."[78] In August, Alexander resigned from the vestry and was replaced by William Cranch. Griffith Coombe was appointed to fill Alexander's position on the committee to get estimates for the building of the church.[78][81]

- August 3, 1806 Masons of the Washington Naval Lodge No. 41 laid the cornerstone of the Sanctuary.[82]

- June 15, 1807 The vestry resolved to "proceed with all possible dispatch, to finish the new Church, Viz, to have the pews on the ground floor Completed, the Pulpit Erected together with the stair cases, & such seats in the front Gallery as may be adequte to accommodate the Clerk & other Gentlemen, or Music [sic] who may attend the Choir, the side Galery [sic] floors to be laid with a pannelling [sic] in front thereof, the plaistering finish'd [sic] and the Joiners work handsomely plainly painted...."[83] It was at least another month before the plaster of the interior cove ceiling was finished by Capitol plasterer William Thackara.[84]

- August 9, 1807 The exterior of the church was finished.[84]

- October 8, 1809 The church was consecrated by the Rt. Rev. Thomas John Claggett, Bishop of Maryland, when, as was the custom, the construction debt had been paid off. Claggett later wrote of the event that he found the church "not large, but sufficiently elegant."[85]

Setting, Size, Design, Layout, Materials, & Features

editThe church was centered on two plots of land (Lots 6 & 7, Square 877) on G Street, SE, given by William Prout.[82] The building was set back approximately 100 feet from and about 4 feet above G Street, which had been cut west to east across the gently sloping hill. Steps led up from the unpaved roadway to a walkway (probably brick) centered on the building.

The design has been incorrectly attributed to Benjamin Latrobe, architect of the Capitol and innumerable other buildings in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington. Records point to Robert Alexander, a protégé of Latrobe, as the original designer of the church. Correspondence by Latrobe's son incorrectly attributes Christ Church Capitol Hill to Latrobe, which may be the genesis of the misattribution.[86]

According to the vestry's request for proposals published in The National Intelligencer (May 28, 30, June 4–13, 1806), the church was constructed of brick.

- Dimensions The original church was 38 feet wide by 45 feet long.

- Entrances There were two exterior doors on the front of the building, now replaced by interior swinging doors from the narthex into the sanctuary.

- Galleries/Balconies Immediately through each door were stairs along the inside of the front wall leading to galleries (or balconies). Vestry records and other references indicate the west gallery was for Marines, the east gallery for enslaved persons, and the south or central portion of the gallery was for the organ, choir, and instrumentalists.[nb 5]

- Pews As was customary at the time, some pews were box-style with doors on them to reduce drafts. The others were high-backed, also probably to block drafts. The pews were divided by two aisles aligned with the exterior doors, with the greatest number of pews in the center. The original church had 42 pews with three reserved for the President, William Prout (land donor), and the Rector. The pews were numbered, and pew rents were charged.

- The church was quite simple. It had a coved ceiling (as today) and clear glass windows. Stained glass was not manufactured in America until the 1830s.[88]

- There is no record of where the pulpit might have been or of its style, other than the vestry journal entry of June 15, 1807, which suggests the pulpit might have been constructed of wood.[89][nb 6]

Subsequent Additions and Modifications

edit- 1824 The church was extended 18 feet to the north, expanding the number of pews to 58. This also provided two additional windows on each side of the nave and a room for the rector on the center south wall.

- 1849 A four-story tower, including the narthex with buttresses and a center door, was added. The narthex measured 40' side and 11'6" deep. The gallery steps were moved to the narthex, allowing stoves on each side of the nave where the steps had been. Battlements, folded sheet-iron finials, and wooden tracery in arched windows were added to give an English neo-Gothic appearance. A bell, still in use, was installed in 1850.

- 1868 Pebble-dash stucco was applied to the front of the church.

- 1874 A separate building was added as a chapel for religious education of children. Around 1898, vestry journals begin to refer to it as "the chapel and parish hall." About 32 feet wide and 56 feet long, it was set back and, as was the custom of the time, not connected to the church.

- 1877 Cast-iron columns were added to keep the roof joists from caving in. The roof was replaced, and the east and west galleries were removed. A shallow recessed chancel may have been added.[91] The stenciled windows may have been installed at this time. The vestry journals show a rather large sum ($465) was paid for glass in the 1877 renovations for windows purchased primarily from memorial funds.

- 1885 The parish hall was extended an additional 16 feet to the north.

- 1891-1892 The fifth story (about 16') of the bell tower was added.[47] Round windows that can be seen only from the outside were added on three of the four sides of the new tower. Also added was an entry vestibule, creating the current arched central entrance.

- Floors and Cellar The 1969 nomination by the National Capitol Planning Commission Landmarks Historian for Christ Church to be placed on the National Register of Historic Places noted that during the 1891 renovation the original joists and floor of the sanctuary were removed, a cellar was dug, and new joists and floors were erected on sustaining walls independent of the outside walls.[92]

- Chancel The renovations included an addition of a chancel covered by a half dome and entered through a high, wide, pointed arch that fought for attention against the elliptical cove.

- Decor The interior was frescoed with ornate grape vines and fruit and elaborately decorated in the Victorian manner. "The colors were those expected of the period: soft, sombre browns and tans and violets."[93][94]

- 1900 Pebble-dash stucco was added to the east and west sides of the church to give the building a uniform appearance.

- 1903 Engraved brass railings were added across the width of the chancel in front of the neo-Gothic carved wood altar, as were a matching lectern for the pulpit and brass railings for the altar rails, given as memorials by parishioners. Brass rails were also added on each side of the steps up to the chancel.

- 1921 Architect Delos H. Smith replaced the grape vine and fruit frescoes with imitation stone to "match" the Gothic aspects of the front of the chancel and deepened the chancel to its present 23'11" by 19' to make room for the organ and choir.[95] The 1880 Hook & Hastings organ was moved to the south gallery located along the original south wall to the east side of the chancel. The south gallery was removed, and electric lights were added. Two stained glass windows were added to the side walls of the chancel, one dedicated to the World War I soldiers of the parish and one to the memory of the Rev. Charles D. Andrews. Claims that the windows were made by the Tiffany Studio in New York cannot be verified.

- 1925 The parish hall was remodeled, with kitchen and nursery areas added on the northwest end, creating a courtyard between the rectory and the parish hall. A basement was added underneath the new addition.

- 1926 The stained glass "Crucifixion" window was installed on the back wall of the chancel, a memorial to the mothers of the church.

- 1953-1954 Architect Horace W. Peaslee directed a major alteration attempting to reconcile the various changes over the years with the original interior design. The Gothic arch leading into the chancel was removed, and the gable roof of the chancel was raised to enable the cove ceiling to be extended the full length of the sanctuary. Two wood copies of the iron columns were installed on each side of the chancel behind the liturgical chairs.[96]

- 1955 The contemporary stained-glass windows in the narthex and second-floor balcony over the narthex, a gift from the estate of Edward Valentine and Mary Elizabeth Howe Conner, were designed and executed by local Washington artists Rowan and Irene LeCompte, who designed 45 windows and six mosaic murals at Washington National Cathedral.[97]

- 1966 A two-story addition to the south end of the parish hall was built, providing office and meeting space and connecting the parish hall to the sanctuary with an entryway. The Sousa stained-glass window in what is now a library/meeting room and the other stained glass on the first and second floors of the addition were added at that time.

- Mid-1970s The choir pews were removed from the front of the chancel, and the choir was relocated onto the floor at the south end of the nave by the organ. A table altar was placed in the center of the chancel.

- 1996 Following extensive study of the changes in liturgical practice embodied in the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, the brass rail at the rear of the chancel was removed. Part of it was reinstalled to the left of the front of the chancel and kneelers placed there. Another part was placed to the right of the pulpit as a rail for congregants walking into the sanctuary down the ramp from the entryway coming from the parish hall. The historic, oversized brass eagle lectern was removed, leaving a single source of address, the pulpit. The paint was removed from the top and arm moldings of the pews, which were treated with a cherry stain, and the bases and backs of the pews were painted white. Pew cushions to match the new carpet runners and chancel carpeting were installed.

- 2015 Replication and replacement of the historic four finials on the top of the church steeple and four lower finials by Wagner Roofing. The new finials are lead coated copper as were the finials that were replaced

- 2016 A half-million dollar renovation of the parish hall included replacement of the heating and air-conditioning systems, replacement of the windows, removal of the stage, construction of multi-level meeting spaces, exposure of the two north-end circular windows, bath renovations, new carpeting, glass panels on the south-end stairs and second floor balcony, and the addition of storage space for tables and chairs. Design was provided by demian/Wilbur/associates.

- 2017 New organ installed, a two-manual, 17-rank instrument with a movable console built by Casavant Frères Ltée, Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec (Opus 3914).

- 2020 Exterior protective coverings of the stained-glass windows were installed by Willet Hauser Architectural Glass under a grant from the DC Preservation League and a bequest from a long time parishioner, Robert Conly.

The many changes of the past 225 years in the church building and parish hall have reflected growth in membership as well as changes in liturgical practice and liturgical taste of the Episcopal Church and the parish.[98] Unlike many historic churches which have either maintained their original features or have had them restored, Christ Church is a blend of the architectural styles and tastes in vogue over its lifetime.[99]

Rectors

editThe 29 rectors of Christ Church Washington Parish, their tenures and theological education are listed below. In the early years of the Episcopal Church, individuals seeking ordination did not always go to theological schools but often studied under the direction of a Bishop or other clergy. In those cases, the ordaining bishop is listed. This list does not include interim and associate rectors who have served the parish on a temporary basis or under the direction of the called rector.

| Rector | Dates of Tenure | Theological Education/Ordaining Bishop | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | George Ralph (1752-1813) | 1795-1807 | Rev. Dr. William Paley; Ordained by Bishop White |

| 2 | Andrew T. McCormick (1761-1841) | 1807-1821 | Ordained by Bishop Claggett |

| 3 | Ethan Allen (1796-1879) | 1823-1830 | Ordained by Bishop Kemp |

| 4 | Frederick Winslow Hatch (1789-1860) | 1830-1835 | Ordained by Bishop Claggett |

| 5 | Henry Henson Bean (1805-1876) | 1836-1848 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 6 | William Hodges (1806-1881) | 1848-1855 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 7 | Joshua Morsell (1815-1883) | 1855-1864 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 8 | Marcus Lafayette Olds (1828-1868) | 1865-1868 | Ordained by Bishop Whipple |

| 9 | Charles Hansford Shield (1824-1894) | 1868-1871 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 10 | William McGuire (DOD circa 1888) | 1871-1873 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 11 | Charles Denison Andrews (1846-1905) | 1873-1887 | General Theological Seminary |

| 12 | Gilbert Fearing Williams (1848-1918) | 1887-1896 | Ordained by Bishop Whittingham |

| 13 | Arthur Shaaf Johns (1842-1921) | 1897-1917 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 14 | David Ransom Covell (1887-1956) | 1917-1919 | General Theological Seminary |

| 15 | William Curtis White (1871-1960) | 1919-1924 | Philadelphia Divinity School |

| 16 | Calvert Egerton Buck (1895-1969) | 1924-1928 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 17 | Edward A. Gabler (1881-1963) | 1928-1946 | General Theological Seminary |

| 18 | Carter Stellwagon Gilliss (1907-1960) | 1946-1951 | Episcopal Theological School, Cambridge, MA |

| 19 | John (Jack) Hiram Stipe (1910-1998) | 1951-1953 | General Theological Seminary |

| 20 | Ivan Edward Merrick (1915-1983) | 1953-1956 | General Theological Seminary |

| 21 | James Joseph Greene (1923-1998) | 1956-1965 | Crozer Theological Seminary |

| 22 | Donald Wylie Seaton, Jr. (1928-1992) | 1965-1968 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 23 | David Dunning (1936-2014) | 1968-1972 | Colgate Rochester/Bexley Hall/Crozer Divinity School |

| 24 | Lynn Chiles McCallum (1943-2010) | 1973-1977 | Virginia Theological Seminary |

| 25 | Henry Lee Hobart Myers (1927-2015) | 1978-1983 | General Theological Seminary |

| 26 | Robert Lee Tate (1950- ) | 1984-1995 | Berkeley Divinity School |

| 27 | Judith Anne Davis (1947- ) | 1996-2008 | Yale Divinity School |

| 28 | Cara Spaccarelli (1980- ) | 2010-2019 | Seminary of the Southwest |

| 29 | John A. Kellogg (1986- ) | 2020- | General Theological Seminary |

Notes

edit- ^ When the District of Columbia was created, it lay within the boundaries of four Episcopal parishes: St. John's Broad Creek, Prince George's County, Maryland; Rock Creek Parish, Montgomery County, Maryland; and Truoro and Fairfax parishes in Fairfax County, Virginia. The new City of Washington and Georgetown were both within the two Maryland parishes.[4]

- ^ Ralph is listed as rector from 1795-1807, however he left Washington Parish in 1797 without resigning, leaving his assistant Andrew McCormick in charge. He came back in 1807, called an annual meeting to elect new vestrymen, resigned, and the newly elected vestry immediately called McCormick as rector. Although his tenure from 1795-1807 was the legal status, the functional reality was that Ralph was at Christ Church from 1795-1797 and McCormick from 1797 to 1821 as assistant-in-charge and then as rector.

- ^ Parish boundaries were important for two reasons. First, historically, state churches functioned as arms of local government providing social services and a vital record keeping function and were often supported by local taxes. The parish boundaries represented the jurisdictional boundaries for services and funding. Second, while the social service function and support from local taxes had been abandoned by the time of the establishment of Washington Parish, the state legislature still had authority to set parish boundaries. This had real consequences because only individuals living within the parish boundaries were eligible to serve on the parish vestry or vote in parish meetings.[23]

- ^ While there are newspaper references to the east gallery being for enslaved persons, there is no record of where the free Blacks early associated with the parish were seated. There is no record of any free Black congregants paying for a pew, but many churches had one or more free pews where persons without means or visitors were seated. Free Blacks could also have been seated in the gallery with enslaved persons.

- ^ It is not known when the first organ was installed in the south balcony. The earliest vestry journal reference to a pipe organ is 1823 when a $5.00 payment was authorized to be paid to a boy to “blow the organ bellows.” In 1831 vestry minutes indicate Jacob Hilbus, a local organ builder, was paid $13.50 for cleaning the organ. Hilbus is mentioned again in 1846 when he was paid for tuning the organ, but it is not known if the first organ was a Hilbus organ. In 1812 he built a one-manual instrument winded by a foot pedal for Christ Church, Alexandria, VA, and in 1819 he built an organ for St. John's Broad Creek, MD.[87]

- ^ Although there is no evidence of the pulpit placement and style, the architectural practice of Episcopal churches of the time was to build pulpits higher than the pews. Christ Church, Alexandria, VA, whose current structure dates from the late 1700s is an example.[90]

References

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ Ennis, Robert Brooks. (1969) “Christ Church, Washington Parish.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 69/70: 141-150. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40067709.

- ^ Taylor, Nancy C. (1969). "Christ Church, Washington Parish". National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ "An Act to Form a New Parish by the Name of Washington Parish to include the City of Washington and Georgetown on Potomac." Passed 26th of December 1794., p. 485, IN: Davis, William A., and District of Columbia. Acts of Congress, in Relation to the District of Columbia, from July 16, 1790, to March 4th, 1831.; "Our History: 250 Years of Loving God." Christ Church Episcopal, Alexandria, VA. https://www.historicchristchurch.org/history; Brydon, G. MacLaren. 1935 "Early Days of the Diocese of Virginia." Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 4(1): 26-46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42968193.

- ^ Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House. 1892. pp. 541–542.

- ^ Hagner, Alexander B. (1909). "History and Reminiscences of St. John's Church, Washington, DC". Records of the Columbia Historical Society. 12: 89.

- ^ a b c Allen, Ethan (c. 1857). Washington Parish, Washington City, 1794. unpublished manuscript, Library of Congress.

- ^ Ennis, Robert Brooks (1969). "Christ Church, Washington Parish". Records of the Columbia Historical Society. 69/70: 126–177. JSTOR 40067709.

- ^ Utley, George Burwell (1913). The Life and Times of Thomas John Claggett. Chicago: RR Donnelley. p. 122.

- ^ a b Allen, Ethan (1860). Clergy in Maryland of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Baltimore: James S. Waters.

- ^ Brydon, G. MacLaren (1935). "Early Days of the Diocese of Virginia". Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church. 4 (1): 26–46. ISSN 0018-2486. JSTOR 42968193.

- ^ Carter, Charles Carroll; diGiacomantonio, William C.; Scott, Pamela (2018). Creating Capitol Hill : place, proprietors, and people. Washington, DC: The United States Capitol Historical Society. ISBN 978-1-5136-3405-0. OCLC 1053902242.

- ^ Johnson, Abby A.; Johnson, Ronald M. (2012). In the Shadow of the United States Capitol : Congressional Cemetery and the Memory of the Nation. Washington, DC: New Academia Pub. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-9860216-0-2. OCLC 824761248.

- ^ Young, James Sterling (1966). The Washington Community 1800-1828. New York: Columbia University.

- ^ Morales-Vázquez, Rubil (2000). "Imagining Washington: Monuments and Nation Building in the Early Capital". Washington History. 12 (1): 12–29. ISSN 1042-9719. JSTOR 40073430.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Robertson, Nan. (2015) Christ Church, Washington Parish. https://washingtonparish.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Christ-Church-History-2015-Final2.pdf

- ^ Overbeck, Ruth Ann; Janke, Lucinda P. (2000). "William Prout: Capitol Hill's Community Builder". Washington History. 12 (1): 122–139. ISSN 1042-9719. JSTOR 40073440.

- ^ Johnson and Johnson 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Johnson and Johnson 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Brown, Gordon S. (2011). The captain who burned his ships : Captain Thomas Tingey, USN, 1750-1829. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-044-6. OCLC 709673881.

- ^ Johnson and Johnson 2012, p. 225.

- ^ Ennis 1969, p.173-175.

- ^ Smith, Kingsley. 2016 "History of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland." https://images.yourfaithstory.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/04/27095254/History-of-the-Episcopal-Diocese-of-Maryland-2016.pdf; "Maryland Vestry Act." http://www.holytrinityepiscopal.church/resources/maryland-vestry-act; Brydon, G. MacLaren. 1935 "Early Days of the Diocese of Virginia." Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 4(1): 26-46.)

- ^ Journal of the Proceedings of the ... Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Diocese of Maryland, 1809.

- ^ Klein, Mary and Kingsley Smith. (June 24–27, 2007) "Racism in the Anglican and Episcopal Church in Maryland." Presentation at the Tri-History Conference of the National Episcopal Historians and Archivists; the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church; Episcopal Woman's History Project, Williamsburg, VA. https://episcopalmaryland.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/04/Racism-in-the-Anglican-and-Episcopal-Church-of-Maryland.pdf

- ^ Amt, Emilie (2017). "Down From the Balcony: African Americans and Episcopal Congregations in Washington County, Maryland, 1800-1864". Anglican and Episcopal History. 86 (1): 1–42. ISSN 0896-8039. JSTOR 26335896.

- ^ Arnebeck, Bob (2014). Slave labor in the capital : building Washington's iconic federal landmarks. Charleston, SC. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-1-62619-721-3. OCLC 889643828.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Johnson and Johnson 2012, p. 31.

- ^ Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery. (n.d.) "Walking Tour: African Americans." https://congressionalcemetery.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/African-American-Walking-Tour-rev.-2021_compressed.pdf

- ^ "The Great Execution: Full Details". Evening Star. July 7, 1865. p. 3.

- ^ Williams, Kimberly Prothro. (2003) Capitol Hill Historic District. DC Historic Preservation Office.

- ^ Journal of the Eighty-Seventh Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Maryland, Baltimore, 1870.

- ^ Journal of the One Hundred and Twelfth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Maryland, Washington, DC, 1895.

- ^ Johnson and Johnson 2012, p. 182-183.

- ^ Sousa, John Philip (1905). Pipetown Sandy. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill.

- ^ a b "A Century Old". Evening Star. May 25, 1895. p. 18.

- ^ "With the Washington Churches: Episcopal (St. Matthew's Chapel)". The Washington Herald. April 25, 1914. p. 9.

- ^ "Easter Sunday in the Churches". Evening Star. April 14, 1873. p. 2.

- ^ "A Wayward Minister". Evening Star. July 8, 1897. p. 2.

- ^ "Unfrocked 14 Years, Visits Church Today". New York Times. June 14, 1912. p. 4.

- ^ Naval History and Heritage Command (January 31, 2023). "Washington, DC: Washington Navy Yard, Overall Views 20th Century".

- ^ Sharp, John G. (2005). History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962 (PDF). Naval District Washington, Washington Navy Yard.

- ^ "Called to Christ Church". Evening Star. March 22, 1897. p. 3.

- ^ "The Rev. D.R. Covell Chosen Christ Church Rector". Evening Star. April 10, 1917. p. 9.

- ^ "Wounded Men are Feasted". The Washington Herald. September 14, 1918. p. 2.

- ^ "Giving of Thanks in All Churches: Protestant Episcopal: Christ Church, Southeast". Evening Star. November 28, 1917. p. 5.

- ^ a b Ennis 1969, p. 171.

- ^ "New York Rector Begins Work Here". Evening Star. July 7, 1928. p. 11.

- ^ "Rev. Edward Gabler, Christ Church Rector, Accepts Florida Call". Evening Star. March 4, 1946. p. 5.

- ^ Journal of the Seventy-Second Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Diocese of Washington, Washington DC, January 27–28, 1967, p. 44.

- ^ "Sousa Buried with Honors". The Washington Times. March 10, 1932. p. 14.

- ^ "Washington Chimes and Those Which Have Aroused Great Admiration in Various Other Lands". Evening Star. December 25, 1938. p. B4.

- ^ Journal of the First Annual Session of the Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Diocese of Washington, Washington DC, May 27–28, 1896, p. 53.

- ^ Journal of the Fiftieth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Diocese of Washington, Chevy Chase, Maryland, May 7, 1945, p. 254.

- ^ "Sesqui Turns Southeast's Attention to Improvements". Evening Star. October 14, 1949. p. B7.

- ^ "Woman Champions Revitalizing Charming Southeast Homes". Evening Star. June 12, 1949. p. A17.

- ^ Dole, Kenneth (March 24, 1952). "Christ Church to Turn Slum into Play Spot: 'Major Contribution' Toward Restoration of Capitol Hill Area Church Plans S.E. Clearance". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Historic Christ Church Disguises Renovation". Evening Star. May 25, 1956. p. 8.

- ^ Smith, Katherine S., ed. (2010). Washington at Home : an Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital (2nd ed.). Baltimore, Md. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8018-9353-7. OCLC 340991413.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Asch, Chris Myers; Musgrove, George Derek (2017). Chocolate City : A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Pr. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-4696-3586-6. OCLC 975982720.

- ^ Dole, Kenneth (January 8, 1966). "Rector Likens City's Challenge to Mining, TNT Experiences: Jefferson's Church Fears Ghetto Split Native of Michigan". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Rector Quits in Turmoil on Ministry to Hippies". The Washington Post. February 20, 1968.

- ^ "Episcopalians Elect Prominent Residents". Evening Star. April 12, 1955. p. 18.

- ^ "D.C. School Supervisor Until 1960". The Washington Post. July 8, 1977.

- ^ "Everyone Home DC: Our Story". January 31, 2023.

- ^ O'Gorek, Elizabeth (July 2, 2019). "Capitol Hill Group Ministry is Now Everyone Home DC". The Hill Rag.

- ^ Barnes, Bart (April 10, 1980). "Old School Building Saved on Capitol Hill: Renovation Saves Old Dent School Building on Capitol Hill". The Washington Post.

- ^ Levy, Claudia (May 25, 1969). "Christ Church Marks 175th Anniversary: Children in Playground". The Washington Post.

- ^ Shriner, Sarah (May 24, 1969). "175th to Draw Many Capitol Hill Leaders". Evening Star. p. 8.

- ^ Hyer, Marjorie (January 9, 1977). "Episcopal Priests Ordained". The Washington Post.

- ^ Hyer, Marjorie (October 31, 1986). "Bishop Urges Church Action on AIDS Care". The Washington Post.

- ^ Levy, Bob (April 21, 1994). "Bikes Stolen, Then Resold Right Away". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Anniversaries Heralded With Music, Speakers: Christ, Capitol Hill, at 200". Washington Diocese. 63 (5): 7. June 1994.

- ^ "Christ Church Installs New Rector". The Hill Rag. October 2010. p. 67.

- ^ Payne III, John H. (October 13, 2017). "A New Organ at Christ Church". The Hill Rag.

- ^ "2018 Capitol Hill Community Achievement Award Honorees". The Hill Rag. February 9, 2018.

- ^ "Meet Christ Church's New Rector". The Hill Rag. November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c Carter, diGiacomantonio, and Scott 2018, p. 139.

- ^ a b Ennis 1969, p. 130.

- ^ Carter, diGiacomantonio, and Scott 2018, p. 253.

- ^ Christ Church, Washington Parish. August 4, 1806 Vestry Minutes.

- ^ a b Ennis 1969, p. 131.

- ^ Ennis 1969, p. 133.

- ^ a b Ennis 1969, p. 135.

- ^ Ennis 1969, p. 137.

- ^ Ennis 1969, p. 139.

- ^ Pipe Organ Database: Jacob Hilbus https://pipeorgandatabase.org/organs?builderID=2832

- ^ "History of Stained Glass". Stained Glass Association of America. January 31, 2023.

- ^ Ennis 1969, p.164.

- ^ Christ Church, Alexandria. Our History: Christ Church in Photos https://www.historicchristchurch.org/history#&gid=1717643736&pid=51

- ^ Ennis 1969, p. 169.

- ^ National Registry of Historic Places--Nomination Form, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, May 25, 1969, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/69000291_text

- ^ Ennis 1969, p.169-171.

- ^ "Old Christ Church, the First Episcopal Church Erected in the District, Remodeled and Improved". Evening Star. October 3, 1891. p. 12.

- ^ Ennis 1969, p.171.

- ^ Ennis 1969, p. 175.

- ^ Dole, Kenneth (October 7, 1955). "Stained-Glass Window Is Installed in Church". The Washington Post.

- ^ Sanctuary Review Committee (January 5, 1989) Christ Church + Washington Parish Bicentennial Celebration, Preservation, and Renewal Steering Committee Report.

- ^ Ennis 1969, p. 173-175.

Bibliography

edit- Carter, Charles Carroll, William C. diGiacomantonio, and Pamela Scott. (2018) Creating Capitol Hill: Place, Proprietors, and People. United States: United States Capitol Historical Society.

- Ennis, Robert Brooks. (1969) "Christ Church, Washington Parish." Records of the Columbia Historical Society 69/70: 126-177. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40067709

- Johnson, Abby A. and Ronald M. Johnson. (2012) In the Shadow of the United States Capitol: Congressional Cemetery and the Memory of the Nation. Washington, DC: New Academia Pub.

- Robertson, Nan. (2015) Christ Church, Washington Parish. https://washingtonparish.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Christ-Church-History-2015-Final2.pdf