The Congressional Cemetery, officially Washington Parish Burial Ground, is a historic and active cemetery located at 1801 E Street, S.E., in Washington, D.C., on the west bank of the Anacostia River. It is the only American "cemetery of national memory" founded before the Civil War.[2] Over 65,000 individuals are buried or memorialized at the cemetery, including many who helped form the nation and Washington, D.C., in the early 19th century.[3]

| Congressional Cemetery | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Established | April 4, 1807 |

| Location | 1801 E Street, S.E., Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Country | United States |

| Type | Private |

| Owned by | Christ Church |

| Size | 35.75 acres (14 ha) |

| Website | Official Site |

| Find a Grave | Congressional Cemetery |

Congressional Cemetery | |

| Coordinates | 38°52′53″N 76°58′40″W / 38.88139°N 76.97778°W |

| Architect | Benjamin Latrobe, others |

| NRHP reference No. | 69000292[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 23, 1969[1] |

| Designated NHL | June 14, 2011 |

| |

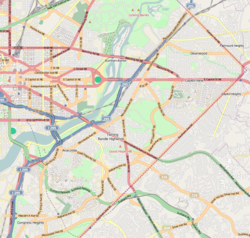

Christ Church, an Episcopal church, owns the cemetery. The U.S. government has purchased 806 burial plots, which are administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Located about a mile and a half (2.4 km) to the southeast of the U.S. Capitol Building, the cemetery is historically associated with the U.S. Congress.[4] The cemetery still sells plots, and is an active burial ground. It is three blocks east of the Potomac Avenue Metro station and two blocks south of the Stadium-Armory Metro station.

Many members of Congress who died while Congress was in session are interred at Congressional Cemetery. Other burials include early landowners and speculators, the builders and architects of early Washington, D.C., Native American diplomats, Washington, D.C. mayors, American Civil War veterans, and 19th century Washington, D.C., families unaffiliated with the federal government.

The cemetery is the resting place of one vice president, one Supreme Court justice, six Cabinet members, nineteen senators, 71 U.S. Representatives, including a former speaker of the House, veterans from every American war, and J. Edgar Hoover, the first FBI director.[3]

The cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 23, 1969, and designated a National Historic Landmark in 2011.[5]

History

edit19th century

editCongressional Cemetery was established by private citizens associated with Christ Church on a 4.5-acre plot in 1807, who later gave the property to the church, which gave it its official name Washington Parish Burial Ground. By 1817 sites were set aside for government legislators and officials; this includes cenotaphs for many legislators buried elsewhere. The cenotaphs, designed by Benjamin Latrobe, each have a large square block with recessed panels set on a wider plinth and surmounted by a conical point.

From 1823 to 1876, the U.S. Congress funded the expansion, enhancement, and maintenance of the cemetery, but it never became a federal institution. Appropriations funded a gravel road from the Capitol to the cemetery, paving within the cemetery, the public vault, fencing, and the gatehouse, and funerals for congressmen and the cenotaphs.[2] During the early part of this period, graves were laid out in a grid pattern in an extension of the grid in the L'Enfant Plan for Washington, and little or no landscaping or plantings were made on the grounds.[6] The grid survives to this day and was extended as the cemetery expanded.

Starting in the late 1840s, the cemetery was influenced by the rural cemetery movement in which the graves were placed in a park-like setting with extensive landscaping. To implement this new vision, the cemetery needed to expand.[6]

Between 1849 and 1869, the cemetery grew in area to 35.75 acres. The original cemetery was located on block 1115 on E Street between 18th and 19th Streets Southeast in 1808. In 1849, it doubled in size by acquiring the block to its south, 1116. In 1853, it expanded to the east on blocks 1130, 1148 and 1149 between F and G Streets Southeast. In 1853–53, the cemetery expanded to the west by acquiring block 1104, between 17th Street and 18th Streets Southeast. In 1858, the cemetery acquired block 1105 and Reservation 13. In 1859, it added blocks 1105 and 1123. Finally, the cemetery reached its current extent of 35.75 acres by growing south to Water Street Southeast with blocks 1106 and 1117 in 1869.[7]

Arsenal Disaster Monument

editIn 1864, an explosion at the nearby Washington Arsenal killed a woman supervisor and 20 teenage girls, most of them Irish, who worked packing explosives and cartridges. President Lincoln led the funeral procession to the cemetery and attended the graveside ceremonies. Later a monument was erected over the graves of 16 of the victims. A sculpture of a grieving young woman stands atop a marble column on the monument.[8] Local artist Lot Flannery, of the Flannery Brothers Marble Manufacturers, sculpted the monument.[9][10]

Eventually the land to the south of the cemetery was transferred to the National Park Service, although the access road to the RFK Stadium parking lot is administered by the DC Sports and Entertainment Commission. In the 1950s, it appeared that the southeast corner of the cemetery would become a part of the right of way for the Southeast-Southwest Freeway. However, protracted environmental litigation halted construction at Pennsylvania Avenue, with the dead end of the freeway being connected by a temporary road to the RFK parking lot and to 17th Street Southeast at the southwest corner of the cemetery.

After 1876, the cemetery was seldom used or supported by Congress. Nevertheless, many wealthy Washingtonians continued to bury family members there, and figures associated with the government who were local residents, including Marine Corps Band director John Philip Sousa and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, are buried there.

20th century

edit| External media | |

|---|---|

| Audio | |

| How Congressional Cemetery Got Its Name, NPR[11] | |

| Video | |

| Washington Friday Journal, July 5, 1996, segments 1:57:30–2:08:00 and 2:27:30–3:00:05, C-SPAN[12] | |

| Congressional Cemetery, Part 1, 27 minutes, C-SPAN[13] | |

| Congressional Cemetery, Part 2, 29 minutes, C-SPAN[14] |

By the 1970s, urban decay, the declining membership of Christ Church, and the declining value of the endowment funded by Christ Church, left the cemetery in serious difficulties. Monuments and burial vaults were in disrepair. Maintenance on buildings had been long delayed. There was no paid staff and minimal funding. Drug dealers and prostitutes began to occupy the cemetery.[15]

21st century

editThe cemetery is still owned by Christ Church but since 1976 it has been managed by the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery (APHCC). Progress on the renovation was very slow until two volunteers became involved. Jim Oliver, then assistant manager of the House Republican Cloakroom, became involved in the late 1980s and helped revive congressional interest in the cemetery. The K-9 Corps, a group of dog owners whose activities helped drive away the drug dealers, was organized in 1997.[15]

Renovation picked up after C-SPAN broadcast a video on the cemetery on July 5, 1996.[12] The following weekend 100 airmen from Andrews Air Force Base arrived unannounced to mow the 35-acre lawn, and a contingent from the Army post at Fort Belvoir followed the next month. A Joint Service Day involving all five branches of the U.S. military has since become an annual tradition. In 2013, a record 328 people participated.[15]

The National Trust for Historic Preservation included the cemetery on its 1997 list of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places and many gifts and donations were soon received. Congress gave $1 million in matching funds in 1999 to create an endowment for basic maintenance, and a 2002 Congressional appropriation funds restoration.[15][16]

The APHCC now hosts over 1,000 volunteers each year working on a wide variety of projects, including planting bulbs, resetting tombstones, pruning trees, adopting and landscaping individual plots, providing research, and writing a quarterly newsletter. Events hosted by the APHCC have included free guided tours on Saturdays, Christmas caroling, Christ Church's Easter services, book signings, Pride 5k race and Dead Man's Run 5k race, Day of the Dog Festival, and Ghosts & Goblets Gala.[3]

In May 2013, Congressional Cemetery hired Topographix, a firm which surveys cemeteries using ground-penetrating radar, to document burials in the cemetery. Although the cemetery had excellent records going back to its founding, many burial sites lacked a marker or had the marker removed or stolen. Additionally, subsidence of some areas and buckling in others has changed the location of some graves.[17] The last time Congressional Cemetery was accurately and completely mapped was 1935.

By the end of 2013, about half the cemetery had been mapped, revealing a potential 2,750 unmarked burial sites. Cemetery staff said many of these burials are probably recorded, but some may be new discoveries. Congressional Cemetery officials said they were one of only 12 cemeteries in the city still accepting burials, and the mapping project would allow it to identify unused space. The mapping project was to be completed in the spring of 2014, and the cemetery said it would use the results to release a mobile phone app which will allow users to search for and locate graves on their own.[18]

In August 2013, the cemetery began using goats to eat and clear the surrounding wooded area of poison ivy, English ivy, grass, and other plants. The 58 "eco-goats", which cost $4,000, are considered more ecologically friendly than mowers and pesticides and provide fertilizer as well. It was the first use of goats inside the beltway. The use of the goats drew widespread international attention and televised reports on BBC World News, Nat Geo, News Hour, NBC Nightly News, Tokyo TV, China CCTV, and Al-Jazeera.[19]

Monuments and structures

editThe Congressional Cemetery is a National Historic Landmark Historic District with nine contributing structures and 186 contributing objects built from 1817 to 1876. Later structures and objects are considered to be "non-contributing" even if they are significant in the cemetery's current appearance.[20]

Cenotaphs

editOf the 186 contributing objects, 168 are the nearly identical Congressional cenotaphs, believed to have been designed by the Architect of the Capitol Benjamin Latrobe.[20] As used at the Congressional Cemetery, the term "cenotaph" includes not only monuments to those buried elsewhere, but also the Latrobe monuments that mark occupied graves of representatives and senators. Some congressmen are buried under a cenotaph, some are buried without one in a different area of the cemetery, and for some the marker is a true cenotaph. James Gillespie (1747–1805), who was reinterred in 1892, has a separate grave and cenotaph.

A cenotaph was erected for each congressman who died in office from 1833 to 1876. The first was for former U.S. Representative James Lent. After Congress appropriated funds and his monument was ordered, his family reinterred the body in New York. Congress erected the monument in 1839 anyway, establishing the tradition of erecting cenotaphs.[21]

The cenotaphs are constructed of Aquia sandstone, as are the White House and the Capitol, and were likewise painted white, forming a visual connections with these nearby symbols of federal government, and a contrast to the surrounding gravestones. They are grouped in rows in the older part of the cemetery where they dominate the landscape.[6]

After the Civil War very few congressmen were buried in the cemetery, as their bodies were commonly shipped to their home states or buried in the new National Cemeteries such as Arlington National Cemetery. Cenotaphs were discontinued in 1876 after Massachusetts Senator George Frisbie Hoar stated that "the thought of being buried beneath one of those atrocities brought new terror to death."[21]

William Thornton, who served as Architect of the Capitol before Latrobe, is the only person honored with a cenotaph who did not serve as a congressman. Former Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill was honored with a cenotaph in 1994, though it is not in the style of a Latrobe cenotaph. After a 1972 plane crash in which their bodies were lost, Hale Boggs and Nicholas Begich share a cenotaph. These are the only cenotaphs erected since 1876.[21]

Public Vault

editThe Public Vault is an early classical revival structure built from 1832 to 1834 with federal funds to store the bodies of government officials prior to burial.

A classical marble facade with baroque scrolls decorates the partially subterranean vault. Double wrought iron doors have the words "PUBLIC VAULT" displayed by means of vent holes.[20] Temporary residents of this vault have included three U.S. presidents: John Quincy Adams (1848), William Henry Harrison (1841), and Zachary Taylor (1850). President Harrison stayed in the vault for three months, three times longer than the time he served as president.[22]

First Lady Dolley Madison was interred in the Public Vault for two years, the longest known interment in the vault, while funds were being raised for her reinterment at Montpelier. Her body was transferred to the Causten family vault, located directly across the path from the Public Vault, for another six years before the funds were raised.[23] First Lady Louisa Catherine Adams has been reported as having been interred in the Public Vault, but other sources report that she was interred in the Causten family vault.[24][25][26] Adams is now buried next to her husband in the United First Parish Church in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Lewis Powell is believed to have spent a night in the vault while avoiding pursuit for his role in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.[22]

Grand funerals

editSeveral nationally important or otherwise remarkable funerals have taken place at the Congressional Cemetery. These funerals featured long formal processions starting at the White House or the Capitol, moving down Pennsylvania Avenue to E Street SE, and then to the cemetery. Parts of this road were specially funded by Congress to facilitate these processions. The form and protocol of these funerals formed the basis for later U.S. state funerals, including those of Presidents Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy.[27]

These funerals include those held to honor:

- George Clinton, vice president, funeral held April 22, 1812. The procession included President James Madison as well as the officers and members of both houses of Congress.[28]

- Jacob Jennings Brown, Commanding General of the United States Army and War of 1812 hero, funeral held February 24, 1828.[29]

- William Henry Harrison, president, 1841. After services at the White House the procession included the new president John Tyler and former president John Quincy Adams, as well as officers and members of the Congress and the state legislature of Maryland, extending over two miles long.[30]

- Abel P. Upshur, Secretary of State, Thomas Walker Gilmer, Secretary of the Navy, Commodore Beverly Kennon, Chief of the Bureau of Construction & Equipment, David Gardiner, former state senator from New York, victims of a February 28, 1844, explosion on the USS Princeton. Virgil Maxcy, chargé d'affaires of the U.S. to Belgium was also killed in the explosion, but he was buried separately in his family plot.[31]

- John Quincy Adams, former president, former senator, and representative, who died in the Capitol, funeral held February 28, 1848.[32] Adams is buried in the United First Parish Church in Quincy, Massachusetts.

- Dolley Madison, former First Lady, funeral held July 16, 1849. President Zachary Taylor and his Cabinet attended services at St. John's Church in Lafayette Square, whence the cortege proceeded to the Public Vault at the Congressional Cemetery.[33]

- Zachary Taylor, president, funeral held July 13, 1850. Proceeding from the White House, the cortege included the new president Millard Fillmore, the Cabinet, the officers and members of both houses of Congress, numerous military units, and Taylor's favorite horse, Old Whitey.[34]

Notable interments

edit- Joseph Anderson (1757–1837), U.S. Senator (Tennessee), Comptroller of the U.S. Treasury

- Alexander Dallas Bache (1806–1867), Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, Charter member National Academy of Sciences

- Philip P. Barbour (1783–1841), U.S. Congressman (Virginia), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court

- Marion Barry (1936–2014), Mayor of the District of Columbia, Civil Rights Movement activist

- Theodorick Bland (1741–1790), U.S. Congressman (Virginia), the first to die in office

- Thomas Blount (1759–1812) U.S. Congressman (North Carolina), Revolutionary War prisoner of war

- Thomas Hale Boggs Jr. (1940–2014), Washington, D.C. lawyer and lobbyist

- John Edward Bouligny (1824–1864), U.S. Congressman (Louisiana), the only member of the Louisiana Congressional delegation to retain his seat after the state seceded during the Civil War (grave unmarked)

- Lemuel Jackson Bowden (1815–1864), U.S. Senator (Virginia), represented Virginia during the Civil War

- John Brademas (1927–2016), U.S. Congressman (Indiana), NYU, President and Chair, Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- Mathew Brady (1822–1896), Civil War photographer

- William A. Burwell (1780–1821), U.S. Congressman (Virginia), private secretary to Thomas Jefferson, U.S. Congressman (Virginia) from 1806 to 1821.

- Levi Casey (1752–1807), U.S. Congressman (South Carolina), general in the South Carolina Militia and American Continental Army

- Herbert L. Clarke (1867–1945), cornet soloist and solo cornetist for the John Philip Sousa Band

- Francis Doyle (1833–1871), brother of Peter Doyle and first Washington, D.C. police officer killed in the line of duty

- Peter Doyle (1843–1907), partner to poet Walt Whitman

- Barbara Gittings (1932–2007), LGBT rights activist

- Owen Thomas Edgar (1831–1929), longest surviving Mexican–American War veteran

- John Forsyth (1780–1841), U.S. Congressman and Senator (Georgia), Governor of Georgia, U.S. Secretary of State

- Henry Stephen Fox (1791–1846), British diplomat

- Mary Fuller (1888–1973), silent film actress

- Elbridge Gerry (1744–1814), Vice President and the only signer of the Declaration of Independence buried in Washington, D.C.

- James Gillespie (1747–1805), U.S. Congressman (North Carolina), colonel of the North Carolina militia in the Revolutionary War

- Count Adam Gurowski (1805–1866), a fiery one-eyed Polish exile and radical

- George Hadfield (1763–1826), architect, superintendent of construction for the U.S. Capitol

- Archibald Henderson (1783–1859), the longest-serving Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps

- Dandridge Featherston Hering (1925–2012), West Point graduate, founder of the San Francisco's Barbary Coast Boating Club

- David Herold (1842–1865), conspirator of the Abraham Lincoln assassination

- J. Edgar Hoover (1895–1972), FBI Director

- Adelaide Johnson (1859–1955), sculptor, social reformer

- Horatio King (1811–1897), U.S. Postmaster General

- Tom Lantos (1928–2008), U.S. Congressman (California), chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the only Holocaust survivor elected to Congress

- Alain LeRoy Locke (1885–1954), African-American writer, philosopher, and educator

- Belva Ann Lockwood (1830–1917), first woman attorney permitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court

- Joseph Lovell (1788–1836), Surgeon General of the U.S. Army

- Charles E. (1845–1923) and Sarah Whitlock Luckett (1860–1917), grandparents of first lady Nancy Reagan and parents of actress Edith Davis

- Alexander Macomb (1782–1841), War of 1812 hero, commanding general of the Army and namesake of Macomb County and Macomb Township, Michigan; Macomb, Illinois, and Macomb Mountain in New York

- Leonard Matlovich (1943–1988), gay rights activist and Air Force veteran

- Robert Mills (1781–1855), architect and designer of the Washington Monument

- Robert Adam Mosbacher (1927–2010), U.S. Secretary of Commerce

- Joseph Nicollet (1786–1843), mathematician and explorer who mapped the upper Mississippi River, namesake of City of Nicollet, County of Nicollet and Nicollet Island in Minnesota

- Daniel Patterson (1786–1831), U.S. Navy commodore

- Peter Pitchlynn (1806–1881), Native American (Choctaw) Chief

- Alfred Pleasonton (1824–1897) U.S. Army officer in the Union cavalry during the Civil War

- Push-Ma-Ta-Ha (c. 1760–1824), Native American (Choctaw) Chief

- Warren M. Robbins (1923–2008), founder of the National Museum of African Art

- Cokie Roberts (1943–2019), journalist for ABC news, daughter of Hale Boggs and Lindy Boggs

- Edith Nourse Rogers (1881–1960), social reformer, U.S. Congresswoman (Massachusetts), sponsor of the G. I. Bill and Women's Army Corps

- Alexander Smyth (1765–1830), lawyer, soldier, U.S. Congressman (Virginia)

- Henry Schoolcraft (1793–1864), geographer, geologist, and ethnologist

- Pat Schroeder (1940–2023), U.S. Representative (Colorado). The first woman elected to represent Colorado in Congress.[citation needed]

- Stephen Solarz (1940–2010), nine-term member of the U.S. House of Representatives (New York), serving from 1975 to 1993.

- John Philip Sousa (1854–1932), composer of many noted military and patriotic marches and conductor of the U.S. Marine Band

- Samuel L. Southard (1787–1842), U.S. Senator (New Jersey), Secretary of the Navy, Governor of New Jersey, president pro tempore of the Senate

- Chief Taza (c. 1849–1876), Apache Chief

- William Thornton (1759–1828), physician, painter, designer and first Architect of the Capitol and superintendent of the U.S. Patent Office

- Thomas Tingey (1750–1829), U.S. Navy commodore

- John Payne Todd (1792–1852), son of Dolley Madison, stepson of President James Madison

- Clyde Tolson (1900–1975), associate director of the FBI

- Joseph Gilbert Totten (1788–1864), military officer, longtime Army Chief of Engineers, regent of the Smithsonian Institution, cofounder of the National Academy of Sciences and namesake of Fort Totten in Washington, D.C.

- Uriah Tracy (1755–1807), U.S. Congressman and Senator (Connecticut)

- William Wirt (1772–1834), U.S. Attorney General, member of the Virginia House of Delegates, author

- Sidney M. Wolfe (1937–2024), physician, co-founder and director of Public Citizen's Health Research Group.

Association and active cemetery

editThe cemetery is administered by the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery (APHCC), which is a non-profit corporation headed by a 15-member board of directors. The association has nine full-time employees, one part-time archivist, and over 500 volunteers.[35] Its mission is:

Historic Congressional Cemetery preserves, promotes, and protects our historic and active burial ground. We respectfully celebrate the legacy of those interred here through education, historic preservation, community engagement, and environmental stewardship.[36]

In 2009, the association retained Oehme, van Sweden & Associates to develop a new landscape plan.[37] The cemetery has approximately 2,000 plots available for sale. On March 20, 2014, the cemetery received its green burial certification from the Green Burial Council. Green burials are allowed in any plot in the cemetery.

K-9 Corps

editCongressional Cemetery is also known for allowing members of the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery (APHCC) to walk dogs off-leash on the cemetery grounds. In addition to their membership dues, K-9 Corps members pay a fee for the privilege of walking their dogs. K-9 Corps members provide about 20% of Congressional Cemetery's operating income. Dog walkers follow a set of rules and regulations and provide valuable volunteer time to restore the cemetery.[38]

The K-9 Corps program is recognized as providing the impetus for the revitalization of Congressional Cemetery, which had fallen into neglect prior to the program's creation.[39] In 2008, the association restricted K-9 membership, placing restrictions on dogwalkers as the program became more popular.[40] The K-9 Corps program has been nationally recognized for creative use of urban green space.[41]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b National Historic Landmark Nomination, p. 4

- ^ a b c "Congressional Cemetery Website". Archived from the original on 2021-05-02. Retrieved 2004-12-29.

- ^ "Congressional Cemetery Government Lots". National Cemetery Administration. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2024-07-17.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places listings for June 24, 2011". National Park Service. June 24, 2011. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c National Historic Landmark Nomination, p. 8.

- ^ "Acquisition of the Squares" (PDF). Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery. 2011-01-14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- ^ NHL Nomination, pp. 11 and 23.

- ^ "Arsenal Monument, (sculpture)". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "Congressional Cemetery Government Lots". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "How Congressional Cemetery Got Its Name". National Public Radio. August 17, 2012. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Washington Friday Journal". C-SPAN. July 5, 1996. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Congressional Cemetery, Part 1". C-SPAN. September 28, 2011. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Congressional Cemetery, Part 2". C-SPAN. September 28, 2011. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Betsy Crosby, The Resurrection of Congressional Cemetery, Historic Capitol Cemetery Revived by Local Preservationists Archived 2012-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, Preservation, January/February, 2012.

- ^ "Fall 2007 Heritage Gazette Newsletter" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ^ Bosworth, Sharon. "Congressional Cemetery Revealed." Archived 2013-12-27 at the Wayback Machine Capital Community News. June 1, 2013. Accessed 2013-12-25.

- ^ Binkovitz, Leah. "'Bone Finder' Plots Unmarked Graves at Historic Congressional Cemetery." Archived 2016-08-08 at the Wayback Machine Washington Post. December 25, 2013. Accessed 2013-12-25.

- ^ Shapira, Ian. "At Congressional Cemetery, Goats Eating Their Way Through an Acre of Poison Ivy." Archived 2017-11-08 at the Wayback Machine Washington Post. August 7, 2013, accessed 2013-08-08; Weber, Joseph. "Goats Are the Go-To in Historic Congressional Cemetery's Eco-Cleanup Quest." Fox News. August 7, 2013, accessed 2013-08-08; "Grazing Goats Will Help Clean Up Historic Congressional Cemetery in Washington." Associated Press. August 7, 2013; "Goats Graze in Historic Washington Graveyard." Archived 2015-04-16 at the Wayback Machine BBC World News. August 7, 2013, accessed 2013-08-08.

- ^ a b c NHL Nomination, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Congressional Cemetery[permanent dead link], 2007, Cenotaph Walking Tour, accessed April 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Josh Swiller, A Walk Through Congressional Cemetery Archived 2012-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, Washingtonian, May 19, 2011.

- ^ American Artifacts: Congressional Cemetery Archived 2016-04-14 at the Wayback Machine, American History TV, CSPAN3, on YouTube, accessed April 16, 2012.

- ^ "The Public Vault". The Washington Post. December 13, 2006. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ "First Lady Louisa C. Adams". Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Johnson and Johnson, p. 139, unequivocally states that Louisa Adams was interred in the Causten family vault the day after her death.

- ^ Johnson and Johnson, Chapter 2, "The Grand Procession to the National Burial Ground."

- ^ Vice President George Clinton Archived 2011-08-17 at the Wayback Machine, reprinted from The National Intelligencer by the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery, accessed April 27, 2012.

- ^ Morris, John D. (2000). Sword of the Border: Major General Jacob Jennings Brown, 1775–1828. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-659-3.

- ^ President William Henry Harrison Archived 2014-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, reprinted from The National Intelligencer by the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery, accessed April 27, 2012.

- ^ Victims of the USS Princeton explosion Archived 2013-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, reprinted from February 29, 1844, edition of The National Intelligencer by the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery, accessed April 27, 2012.

- ^ President John Quincy Adams Archived 2013-10-09 at the Wayback Machine includes reprints from 1848 editions of the National Intelligencer, Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery, accessed May 2, 2012.

- ^ First Lady Dolley P. Madison Archived 2013-10-09 at the Wayback Machine includes reprints from 1849 editions of the National Intelligencer, Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery, accessed May 2, 2012.

- ^ President Zachary Taylor Archived 2013-10-11 at the Wayback Machine includes reprints from 1850 editions of the National Intelligencer, Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery, accessed May 2, 2012.

- ^ "Meet Our Staff". Congressional Cemetery. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "About Us". Historic Congressional Cemetery. Archived from the original on 2021-01-17. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- ^ "2009 Annual Report" (PDF). Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery. 2011-01-14. p. 10.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cemetery Dogs". Archived from the original on 2017-06-15. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ^ Holeywell, Ryan (December 22, 2006). "Congressional Cemetery's Slow Resurrection". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Dogwalking Program Overview". Archived from the original on 2021-05-02. Retrieved 2004-12-29.

- ^ "Cemetery Dogs | Serving the Historic Congressional Cemetery". Archived from the original on 2017-06-15. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

Sources

edit- Boggs Roberts, Rebecca; Schmidt, Sandra K. (2012). Historic Congressional Cemetery. Columbia, SC: Arcadia Press (Images of America). ISBN 978-0738592244.

- Johnson, Abby A.; Ronald M. Johnson (2012). In the Shadow of the United States Capitol: Congressional Cemetery and the Memory of the Nation. New Academia Publishing. p. 434. ISBN 978-0986021626.

- Sienkewicz, Julia A. (2009). "Congressional Cemetery National Historic Landmark Nomination" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- History of the Congressional Cemetery[permanent dead link], U.S. Senate, December 6, 1906

- Congressional Cemetery, Historic American Landscapes Survey, 2005

- Moeller, Gerard Martin; G. Martin Moeller Jr. (2012). AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. (5th ed.). JHU Press. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-1421406268.

External links

edit- Official website with map and index

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. DC-424, "Congressional Cemetery, Latrobe Cenotaphs"

- Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) No. DC-1, "Congressional Cemetery"

- CemeteryDogs.org Archived 2017-06-15 at the Wayback Machine, K9 Corps website

- Cemetery Dog, YouTube video

- QR codes at Congressional Cemetery, Channel 7 ABC WJLA in Washington, July 17, 2012

- C-SPAN American History TV Tour of Congressional Cemetery

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Congressional Cemetery

- Congressional Cemetery at Find a Grave