Cartagena (/ˌkɑːrtəˈheɪnə/ KAR-tə-HAY-nə), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (Spanish: [kaɾtaˈxena ðe ˈindjas] ), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, along the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a link in the route to the West Indies provides it with important historical value for world exploration and preservation of heritage from the great commercial maritime routes.[5] As a former Spanish colony, it was a key port for the export of Bolivian silver to Spain and for the import of enslaved Africans under the asiento system. It was defensible against pirate attacks in the Caribbean.[6] The city's strategic location between the Magdalena and Sinú rivers also gave it easy access to the interior of New Granada and made it a main port for trade between Spain and its overseas empire, establishing its importance by the early 1540s.

Cartagena | |

|---|---|

District and city | |

| Cartagena de Indias | |

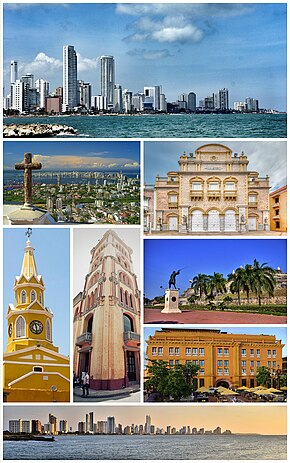

Top: Bocagrande Harbor. Second row: View of Santa Cruz Manga Island, Heredia Theatre. Third row: ClockTower (Torre del Reloj), Cloister of San Agustín (University of Cartagena), San Felipe Barajas Castle (Castillo de San Felipe de Barajas) (above), Charleston Hotel (below). Bottom: City Skyline. | |

| Nicknames: La ciudad mágica (The Magic City) La ciudad cosmopolita (The Cosmopolitan City) La heroica (The Heroic) El corralito de piedra (The Rock Corral) La fantástica (The Fantastic) | |

| Motto: "Por Cartagena" | |

| |

| Coordinates: 10°24′N 75°30′W / 10.400°N 75.500°W | |

| Country | Colombia |

| Department | Bolívar |

| Region | Caribbean |

| Foundation | 1 June 1533 |

| Founded by | Pedro de Heredia |

| Named for | Cartagena, Spain |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | William Jorge Dau Chamat[1] |

| Area | |

• District and city | 83.2 km2 (32.1 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 597.7 km2 (230.8 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2 m (7 ft) |

| Population (2020[3]) | |

• District and city | 914,552 |

| • Rank | Ranked 5th |

| • Density | 11,000/km2 (28,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,028,736[2] |

| • Metro density | 1,721/km2 (4,460/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Cartagenero(s) (in Spanish) |

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total | $17.1 billion[4] |

| • Per capita | $15,600 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (COT) |

| Postal code | 130000 |

| Area code | 57 + 5 |

| Patron saints | Saint Catherine and Saint Sebastian |

| Average temperature | 30 °C (86 °F) |

| City tree | Arecaceae |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv, vi |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Reference no. | 285 |

| Region | Latin America and Caribbean |

Modern Cartagena is the capital of the Bolívar Department, and had a population of 876,885 according to the 2018 census,[7] making it the second-largest city in the Caribbean region, after Barranquilla, and the fifth-largest city in Colombia. The metropolitan area of Cartagena is the sixth-largest urban area in the country, after metropolitan area of Bucaramanga. Economic activities include the maritime and petrochemical industries, as well as tourism.

The present city—named after Cartagena, Spain and by extension, the historic city of Carthage—was founded on 1 June 1533, making it one of South America’s oldest colonial cities;[8] but settlement by various indigenous people in the region around Cartagena Bay dates from 4000 BC. During the Spanish colonial period Cartagena had a key role in administration and expansion of the Spanish empire. It was a center of political, ecclesiastical, and economic activity.[9] In 1984, Cartagena's colonial walled city and fortress were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It was also the site of the Battle of Cartagena de Indias in 1741 during the War of Jenkins' Ear between Spain and Britain.

History

editPre-Columbian era: 4000 BC – AD 1500

editThe Puerto Hormiga Culture, founded in the Arjona Municipality of the Bolívar Department in the Caribbean coast region, particularly in the area from the Sinú River Delta to the Cartagena Bay, appears to be the first documented human community in what is now Colombia.[10] Archeologists estimate that around 4000 BC, the formative culture was located near the boundary between the current departments of Bolívar and Sucre. In this area, archeologists have found the most ancient ceramic objects of the Americas, dating from around 4000 BC. The primary reason for the proliferation of primitive societies in this area is thought to have been the relatively mild climate and the abundance of wildlife, which allowed the hunting inhabitants a comfortable life.[11][12][13]

Archeological investigations date the decline of the Puerto Hormiga culture and its related settlements to be ~3000 BC. The rise of a much more developed culture, the Monsú, who lived at the end of the Dique Canal near today's Cartagena neighborhoods Pasacaballos and Ciénaga Honda at the northernmost part of Barú Island, has been hypothesized. The Monsú culture appears to have inherited the Puerto Hormiga culture's use of the art of pottery and also to have developed a mixed economy of agriculture and basic manufacture. The Monsú people's diet was based mostly on shellfish and fresh and salt-water fish.[14]

The development of the Sinú society in what is today the departments of Córdoba and Sucre, eclipsed these first developments around the Cartagena Bay area. Until the Spanish colonization, many cultures derived from the Karib, Malibu and Arawak language families lived along the Colombian Caribbean coast. In the late pre-Columbian era, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta was home to the Tayrona people, whose language was closely related to the Chibcha language family.[15][16]

Around AD 1500, the area was inhabited by different tribes of the Carib language family, more precisely the Mocanae sub-family.

Mocana villages of the Carib people around the Bay of Cartagena included:[17]

- on a sandy island facing the ocean in what is present-day downtown: Kalamarí (Calamari)

- on the island of Tierrabomba: Carex

- on Isla Barú, then a peninsula: Bahaire

- on present-day Mamonal, the eastern coast of the exterior bay: Cospique

- in the suburban area of Turbaco: Yurbaco Tribe

Heredia found these settlements "...largely surrounded with the heads of dead men placed on stakes."[18]: 481

Some subsidiary tribes of the Kalamari lived in today's neighborhood of Pie de la Popa, and other subsidiaries from the Cospique lived in the Membrillal and Pasacaballos areas. Among these, according to the earliest documents available, the Kalamari had preeminence. These tribes, though physically and administratively separated, shared a common architecture, such as hut structures consisting of circular rooms with tall roofs, which were surrounded by defensive wooden palisades.[19]

First sightings by Europeans: 1500–1533

editRodrigo de Bastidas traveled to the Pearl Coast and the Gulf of Uraba in 1500–01. On 14 February 1504, Ferdinand V contracted Juan de la Cosa's voyage to Uraba. However, Juan de la Cosa died in 1510 along with 300 of Alonso de Ojeda's men, after an armed confrontation with indigenous people, and before Juan de la Cosa could get possession of the Gulf of Urabá area. Similar contracts were signed in 1508 with Diego de Nicuesa for the settlement of Veragua and with Alonso de Ojeda for the settlement of Uraba, "where gold had already been obtained on earlier voyages," according to Floyd.[20][18]

After the failed effort to found Antigua del Darién in 1506 by Alonso de Ojeda and the subsequent unsuccessful founding of San Sebastián de Urabá in 1510 by Diego de Nicuesa, the southern Caribbean coast became unattractive to colonizers. They preferred the better known Hispaniola and Cuba.[21]

Although the royal control point for trade, the Casa de Contratación gave permission to Rodrigo de Bastidas (1460–1527) to again conduct an expedition as adelantado to this area, Bastidas explored the coast and sighted the Magdalena River Delta in his first journey from Guajira to the south in 1527, a trip that ended in the Gulf of Urabá, the location of the failed first settlements. De Nicuesa and De Ojeda noted the existence of a big bay on the way from Santo Domingo to Urabá and the Panama isthmus, and that encouraged Bastidas to investigate.[22][23][24][25]

Colonial era: 1533–1717

editUnder contract to Queen Joanna of Castile, Pedro de Heredia entered the Bay of Cartagena with three ships, a lighter, 150 men, and 22 horses, on 14 January 1533. He soon found the village of Calamari abandoned. Proceeding onwards to Turbaco, where Juan de la Cosa had been mortally wounded 13 years earlier, Heredia fought an all-day battle before claiming victory. Using India Catalina as a guide, Heredia embarked on a three-month exploration expedition. He returned to Calamari in April 1533 with gold pieces, including a solid gold porcupine weighing 132 pounds. In later expeditions, Heredia raided the Sinú tombs and temples of gold. His rule as governor of Cartagena lasted 22 years, before perishing on his return to Spain in 1544.[17]: 14–17 [18]: 479–85

Cartagena was founded on 1 June 1533 by the Spanish commander, Pedro de Heredia, in the former location of the indigenous Caribbean Calamarí village. The town was named after the port city of Cartagena, in Murcia in southeast Spain, where most of Heredia's sailors had resided.[27] King Philip II gave Cartagena the title of "city" (ciudad) in 1574, adding "most noble and loyal" in 1575.[17]: 23

The city's increasing importance as a port for the export of Bolivian silver from Potosí to Spain, made it an obvious target for pirates and corsairs, encouraged by France, England, and Holland. In 1544, the city was pillaged by 5 ships and 1,000 men under the command of the French pirate Jean-François Roberval, who took advantage of the city still without walls. Heredia was forced to retreat to Turbaco until a ransom was paid. A defensive tower, San Felipe del Boqueron, was built in 1566 by Governor Anton Davalos. It was supposed to protect the anchorage and the Bahia de las Animas, a water lane into Plaza de lar Mar (current day Plaze de la Aduana), but the fort's battery had limited range. Then the French pirate Martin Cote struck in 1569 with 1,000 men, ransacking the city.[17]: 23–24 [28]: 97–98

A few months after the disaster of the invasion of Cote, a fire destroyed the city and forced the creation of a firefighting squad, the first in the Americas.[29][full citation needed]

In 1568, Sir John Hawkins tried to persuade Governor Martín de las Alas to open a trade fair in the city which would allow his men to sell foreign goods. This was a violation of Spanish law, which forbade trade with foreigners. Many in the settlement suspected this would have allowed Hawkins to sack the port afterwards; and as such the governor declined. Hawkins bombarded the city for 8 days, but failed to make any significant impacts and withdrew.[30][31] Then Francis Drake attacked in April 1586 with 23 ships and 3,000 men. Drake burned 200 houses and the cathedral, departing only after a ransom was paid a month later.[17]: 24 [32][33]

Spain then commissioned Bautista Antonelli in 1586 to design a master scheme for defending its Caribbean ports. This included a second visit to Cartagena in 1594 when he drew up plans for a walled city.[28]

In 1610, the Holy Office of the Inquisition was established in Cartagena and The Palace of Inquisition was completed in 1770. Sentences were pronounced in the main city plaza, today's Plaza de Bolivar, during the Autos de Fe ceremonies. Crimes under its jurisdiction included those of heresy, blasphemy, bigamy and witchcraft. A total of 767 people were punished, which ranged from fines, wearing a Sanbenito, life imprisonment, or even the death of five. The Inquisition was abolished with independence in 1811.[17]: 28

The first slaves were brought by Pedro de Heredia to work as "macheteros", clearing the underbrush. By the 17th century, Cartagena had become an important slave market in the New World, centered around the Plaza de los Coches. European slave traders began to bring enslaved peoples from Africa during this period. Spain was the only European power that did not establish factories in Africa to purchase slaves and therefore the Spanish Empire relied on the asiento system, awarding merchants from other European nations the license to trade enslaved people to their overseas territories.[34][35][36][17]: 30 [28]: 135

Gov. Francisco de Murga made the Inner Bay an "impregnable lagoon", according to Segovia, which included the forts El Boquerón, Castillo Grande, Manzanillo, and Manga. Besides the walls built to defend the historic district of Calamari, Francisco de Murga enclosed Getsemani with protective walls starting in 1631. This included the battery of Media Luna of San Antonio, located between the bastions of Santa Teresa and Santa Barbara, which protected the only gate and causeway to the mainland.[28]: 98, 130

The practice of Situado is exemplified in the magnitude of the city's subsidy between 1751 and 1810, when the city received the sum of 20,912,677 Spanish reales.[32][33][page needed]

The Raid on Cartagena, in April 1697 during the Nine Years' War, by Sir Bernard Desjean, Baron de Pointis and Jean Baptiste Ducasse was a severe blow to Cartagena. The Baron's forces included 22 large ships, 500 cannon, and 4,000 troops, while Ducasse's forces consisted of 7 ships and 1,200 buccaneers. They quickly overwhelmed Sancho Jimeno de Orozco's force of 30 men in the San Luis de Bocachica fortification. Then, San Felipe de Barajas also fell and the city came under bombardment. When the Half Moon Gate was breached and Getsemani island occupied, Governor Diego de los Rios capitulated. The Baron left after a month of plunder (roughly 2 million livres) and Ducasse followed a week later.[17]: 31–32

When King Philip II employed the Italian engineer Juan Bautista Antonelli to design a master plan of fortifications for Cartagena, construction would actually continue for the next two hundred years. On 17 March 1640, three Portuguese ships under the command of Rodrigo Lobo da Silva, ran aground in the Bocagrande Channel. This accelerated the formation of a sand bar, which soon connected the Bocagrande Peninsula to the island of Tierrabomba. The defense of the bay then shifted to two forts on either side of Bocachica, San Jose and San Luis de Bocachica. San Luis was replaced by San Fernando after the 1741 English raid. The next narrow passage was formed by the Island of Manzanillo, where San Juan del Manzanillo was constructed and Santa Cruz O Castillo Grande opposite on Cruz Grande at Punta Judio, both connected by a floating chain. Finally, there was San Felipe del Boquerón, later San Sebastián del Pastelillo. The city itself was circled with a ring of bastions connected by curtains. The island of Getsemani was also fortified. Protecting the city on the landward side, atop San Lázaro hill, was the Castillo San Felipe de Barajas[37] named in honor of Spain's King Philip IV and Governor Pedro Zapata de Mendoza, Marquis of Barajas' father, the Count of Barajas. Completed in 1654, the fort was expanded in the 18th century, and included underground corridors and galleries.[17]: 25–26 [38][28]: 76 [28]: 69–72

Viceregal era: 1717–1811

editThe 18th century began poorly for the city economically, as the Bourbon dynasty discontinued the Carrera de Indias convoys. However, with the establishment of the Viceroyalty of New Granada and the constant Anglo-Spanish conflicts, Cartagena took on the stronghold as the "gateway to the Indies of Peru". By 1777, the city included 13,700 inhabitants with a garrison of 1300. The population reached 17,600 in 1809.[28]: 31–33, 36

In 1731, Juan de Herrera y Sotomayor founded the Military Academy of Mathematics and Practice of Fortifications in Cartagena. He is also known for designing the Puerta del Reloj starting in 1704.[28]: 43, 138–39

1741 attack

editStarting in mid-April 1741, the city endured a siege by a large British armada under the command of Admiral Edward Vernon. The engagement, known as Battle of Cartagena de Indias, was part of the larger War of Jenkins' Ear. The British armada included 50 warships, 130 transport ships, and 25,600 men, including 2,000 North American colonial infantry. The Spanish defense was under the command of Sebastián de Eslava and Don Blas de Lezo. The British were able to take the Castillo de San Luis at Bocachica and land marines on the island of Tierrabomba and Manzanillo. The North Americans then took La Popa hill.[17]: 33–35

Following a failed attack on San Felipe Barajas on 20 April 1741, which left 800 British dead and another 1,000 taken prisoner, Vernon lifted the siege. By that time he had many sick men from tropical diseases. An interesting footnote to the battle was the inclusion of George Washington's half brother, Lawrence Washington, among the North American colonial troops. Lawrence later named his Mount Vernon estate in honor of his commander.[17]: 35–36

During this era, José Ignacio de Pombo thrived as merchant.[40]

Silver Age (1750–1808)

editIn 1762, Antonio de Arebalo published his Defense Plan, the Report on the estate of defense on the avenues of Cartagena de Indias. This engineer continued the work to make Cartagena impregnable, including the construction from 1771 to 1778, of a 3400 yards long underwater jetty across the Bocagrande called the Escollera. Arebalo had earlier completed San Fernando, and the fort-battery of San Jose in 1759, then added El Angel San Rafael on El Horno hill as added protection across the Bocachica.[28]: 55, 81–94

Among the censuses of the 18th century was the special census of 1778, imposed by the governor of the time, D. Juan de Torrezar Diaz Pimienta – later Viceroy of New Granada – by order of the Marquis of Ensenada, Minister of Finance – so that he would be provided numbers for his Catastro tax project, which imposed a universal property tax he believed would contribute to the economy while at the same time increasing royal revenues dramatically. The census of 1778, besides having significance for economic history, required each house to be described in detail and its occupants enumerated, making the census an important tool[41] The census revealed what Ensenada had hoped. However, his enemies in the court convinced King Charles III to oppose the tax plan.

1811 to the 21st century

editFor more than 275 years, Cartagena was under Spanish rule. With Napoleon's imprisonment of Charles IV and Ferdinand VII, and the start of the Peninsular War, the Latin American wars of independence soon followed. In Cartagena, on 4 June 1810, Royal Commissioner Antonio Villavicencio and the Cartagena City Council banished the Spanish Governor Francisco de Montes on suspicions of sympathy for the French emperor and the French occupation forces which overthrew the king. A Supreme Junta was formed, along with two political parties, one led by Jose Maria Garcia de Toledo representing the aristocrats, and a second led by Gabriel and German Piñeres representing the common people of Getsemani. Finally, on 11 November, a Declaration of Independence was signed proclaiming "a free state, sovereign and independent of all domination and servitude to any power on Earth".[17]: 49–51 The support for a declaration of independence by working class leader and artisan Pedro Romero was key in pushing the Junta to adopting it.[44]

Spain's reaction was to send a "pacifying expedition" under the command of Pablo Morillo, The Pacifier, and Pascual de Enrile, which included 59 ships, and 10,612 men. The city was placed under siege on 22 August 1815. The city was defended by 3000 men, 360 cannons, and 8 ships plus ancillary small watercraft, under the command of Manuel del Castillo y Rada and Juan N. Enslava. However, by that time, the city was under the rule of the Garcia de Toledo Party, having exiled German and Gabriel Piñeres, and Simon Bolivar. By 5 December, about 300 people per day died from hunger or disease, forcing 2000 to flee on vessels provided by the French mercenary Louis Aury. By that time, 6000 had died. Morillo, in retaliation after entering the city, shot nine of the rebel leaders on 24 February 1816, at what is now known as the Camellon de los Martires. These included José María García de Toledo and Manuel del Castillo y Rada.[17]: 55–60

Finally, a patriot army led by General Mariano Montilla, supported by Admiral José Prudencio Padilla, laid siege to the city from August 1820 until October 1821. A key engagement was the destruction of almost all of the royalist ships anchored on Getsemani Island on 24 June 1821. After Governor Gabriel Torres surrendered, Simon Bolivar the Liberator, bestowed the title "Heroic City" onto Cartagena. The Liberator spent 18 days in the city from 20 to 28 July 1827, staying in the Government Palace in Proclamation Square and the guest of a banquet hosted by Jose Padilla at his residence on Calle Larga.[17]: 60, 67

Unfortunately, the toll of war, in particular from Morillo's siege long affected the city. With the loss of the funds it had received as the main colonial military outpost, and the loss of population, the city deteriorated. It suffered a long decline in the aftermath of independence, and was largely neglected by the central government in Bogotá. In fact, its population did not reach pre-1811 numbers until the start of the 20th century.[45]

These declines were also due to disease, including a devastating cholera epidemic in 1849. The Canal del Dique that connected it to the Magdalena River also filled with silt, leading to a drastic reduction in the amount of international trade. The rise of the port of Barranquilla only compounded the decline in trade. During the presidency of Rafael Nuñez, who was a Cartagena native, the central government finally invested in a railroad and other infrastructure improvements and modernization that helped the city to recover.[46]

Cartagena is the capital of the Bolívar department.[47]

Geography

editLocation

editCartagena is located to the north of Colombia, at 10°25'N 75°32'W.[48] It faces the Caribbean Sea to the west. To the south is the Cartagena Bay, which has two entrances: Bocachica (Small Mouth) in the south, and Bocagrande (Big Mouth) in the north. Its coastal line is characterized morphologically by dissipative beaches.[49]

Cartagena bay is an estuary with an area of approximately 84 km2.[50]

Neighborhoods

editNorthern area

editIn this area is the Rafael Núñez International Airport, located in the neighborhood of Crespo, ten minutes' drive from downtown or the old part of the city and fifteen minutes away from the modern area. Zona Norte, the area located immediately north of the airport, contains hotels, the urban development office of Barcelona de Indias, and several educational institutions.[citation needed] The old city walls, which enclose the centro or downtown area and the neighborhood of San Diego, are located to the southwest of Crespo. On the Caribbean shore between Crespo and the old city lie the neighborhoods of Marbella and El Cabrero.

Downtown

editThe Downtown area of Cartagena has varied architecture, mainly a colonial style, but republican and Italian style buildings, such as the cathedral's bell tower, can be seen.

The main entrance to downtown is the Puerta del Reloj (Clock Gate), which exits onto the Plaza de los Coches (Square of the Carriages).[51] A few steps farther is the Plaza de la Aduana (Customs Square), next to the mayor's office. Nearby is San Pedro Claver Square and the church also named for Saint Peter Claver, where the body of the Jesuit saint ('Saint of the African slaves') is kept in a casket, as well as the Museum of Modern Art.[Note 1]

Nearby is the Plaza de Bolívar (Bolívar's Square) and the Palace of Inquisition. Plaza de Bolívar (formerly known as Plaza de La Inquisicion) is essentially a small park with a statue of Simón Bolívar in the center. This plaza is surrounded by balconied colonial buildings. Shaded outdoor cafes line the street.

The Office of Historical Archives devoted to Cartagena's history is not far away. Next to the archives is the Government Palace, the office building of the Governor of the Department of Bolivar. Across from the palace is the Cathedral of Cartagena, which dates back to the 16th century.

Another religious building of significance is the Iglesia de Santo Domingo in front of Plaza Santo Domingo (Santo Domingo Square). In the square is the sculpture Mujer Reclinada ("Reclining Woman"), a gift from the notable Colombian artist Fernando Botero. Nearby is the Tcherassi Hotel, a 250-year-old colonial mansion renovated by designer Silvia Tcherassi.

In the city is the Augustinian Fathers Convent and the University of Cartagena. This university is a center of higher education opened to the public in the late 19th century. The Claustro de Santa Teresa (Saint Theresa Cloister), which has been remodeled and has become a hotel operated by Charleston Hotels. It has its own square, protected by the San Francisco Bastion.

A 20-minute walk from downtown is the Castillo de San Felipe de Barajas, located in el Pie de la Popa (another neighborhood), one of the greatest fortresses built by the Spaniards in their colonies. The tunnels were all constructed in such a way as to make it possible to hear footsteps of an approaching enemy. Some of the tunnels are open for viewing today.

Cartagena's walled Old City is known in part for its lush plazas,[54] and sherbet-hued Spanish colonial buildings.[55]

San Diego

editSan Diego was named after the local San Diego Convent, now known as the Beaux Arts University Building. In front of it is the Convent of the Nuns of the Order of Saint Clare, now the Hotel Santa Clara. In the surrounding area is Santo Toribio Church, the last church built in the Walled City. Next to it is Fernández de Madrid Square, honoring Cartagena's hero, José Fernández de Madrid, whose statue can be seen nearby.

Inside the Old City[clarification needed] is found Las Bóvedas (The Vaults),[56] a construction attached to the walls of the Santa Catalina Fortress. From the top of this construction the Caribbean Sea is visible.

Getsemaní

editOnce a district characterized by crime, Getsemaní, just south of the ancient walled fortress, has become "Cartagena's hippest neighborhood and one of Latin America's newest hotspots", with plazas that were once the scene of drug dealing being reclaimed and old buildings being turned into boutique hotels.[58]

Getsemaní has become a "Ciudad Mural" to rescue the values, customs, traditions and anecdotes of the people.[1]

Bocagrande

editThe Bocagrande (Big Mouth) is an area known for its skyscrapers. The area contains the bulk of the city's tourist facilities, such as hotels, shops, restaurants, nightclubs and art galleries. It is located between Cartagena Bay to the east and the Caribbean Sea to the west, and includes the two neighborhoods of El Laguito (The Little Lake) and Castillogrande (Big Castle). Bocagrande has long beaches and much commercial activity is found along Avenida San Martín (Saint Martin Avenue).[59]

The beaches of Bocagrande, lying along the northern shore, are made of volcanic sand, which is slightly grayish in color. This makes the water appear muddy, though it is not. There are breakwaters about every 180 meters (200 yd).[citation needed]

On the bay side of the peninsula of Bocagrande is a seawalk. In the center of the bay is a statue of the Virgin Mary. The Naval Base is also located in Bocagrande, looking at the Bay.

Climate

editCartagena features a tropical wet and dry climate (Köppen: Aw). Humidity averages around 90%, with the rainy season typically lasting in May–November. The climate tends to be hot and windy.

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) is one of the coastal ocean factors having a bearing on the regional climate.[60]

| Climate data for Cartagena (Rafael Núñez International Airport) 1991–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 40.0 (104.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

38.0 (100.4) |

38.0 (100.4) |

40.0 (104.0) |

39.8 (103.6) |

39.0 (102.2) |

38.0 (100.4) |

39.6 (103.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

40.0 (104.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.1 (88.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.0 (75.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19.0 (66.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.5 (0.02) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.2 (0.01) |

18.6 (0.73) |

117.4 (4.62) |

92.5 (3.64) |

121.1 (4.77) |

127.5 (5.02) |

133.1 (5.24) |

236.5 (9.31) |

178.3 (7.02) |

44.7 (1.76) |

1,073.8 (42.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 7.0 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 8.9 | 2.6 | 70.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 82 | 81 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 272.8 | 240.1 | 238.7 | 210.0 | 192.2 | 189.0 | 207.7 | 198.4 | 171.0 | 170.5 | 186.0 | 241.8 | 2,518.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.8 | 8.5 | 7.7 | 7.0 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 7.8 | 6.9 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 11.6 | 11.8 | 12.1 | 12.4 | 12.6 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 12.5 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 11.7 | 11.5 | 12.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 75.9 | 66.6 | 63.8 | 56.6 | 49.3 | 49.5 | 52.9 | 51.4 | 46.8 | 46.2 | 53.2 | 67.7 | 56.7 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 11 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 12 |

| Source 1: Instituto de Hidrologia Meteorologia y Estudios Ambientales (humidity, sun 1971-2010)[61][62][63][64] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas(daylight)[65] Nomadseason(UV index)[66] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit

|

|

|

Ethnic composition

editAccording to the figures presented by DANE from the 2005 census, the ethnographic composition of the city is:[67]

- Whites and Mestizos: 63.2%

- Black, mulatto, Afro-Colombian or Afro-descendant: 36.1%

- Palenquero: 0.3%

- Indigenous: 0.2%

- ROM: 0.1%

- Raizal: 0.1%

Economy

editThe main economic activities in Cartagena are industry, tourism, and commerce. The port of Cartagena is one of the largest of South America.

Industry

editOther prominent companies include Cementos Argos, Miss Colombia, Kola Román, Indufrial, Amazon Pepper, Vikings SA, Distribuidora Ltda Refrigeration, Central Ingenio Colombia, Perfumery Lemaitre, Cartagena Refinery Cellux Colombiana SA, Flour Three Castles, Polyban International SA, SABMiller, Dow Chemical, Cemex, Dole, and Abocol.[citation needed].

Miss Colombia

editIn 1934, Miss Colombia was founded in Cartagena de Indias. Known as Concurso Nacional de Belleza de Colombia (National Beauty Contest of Colombia), it is a national beauty pageant in Colombia. The winner, Señorita Colombia, is sent to Miss Supranational and the first runner-up, Señorita Colombia Internacional or Virreina, to Miss International.[68]

There is also a local beauty contest held with many of the city's neighbourhoods nominating young women to be named Miss Independence.[69]

Free zones

editFree zones are areas within the local territory which enjoy special customs and tax rules.[70][71] They are intended to promote the industrialization of goods and provision of services aimed primarily at foreign markets and also the domestic market.[citation needed]

- Parque Central Zona Franca: Opened in 2012 the zone is located in the municipality of Turbaco, within the District of Cartagena de Indias. It covers an area of 115 hectares (284+1⁄4 acres).[72] It has a permamente Zone (Phase 1 – Phase 2) and a Logistics and Commercial Zone for SMEs.[citation needed]

- Zona Franca Industrial Goods and Services ZOFRANCA Cartagena SA: located 14 kilometers (8+3⁄4 miles) from the city center, at the end of the industrial sector and has Mamonal private dock.[citation needed]

- Zona Franca Turística en Isla De Barú: located on the island of Baru, within the swamp Portonaito. Approved in 1993 the tourist zone offers waterways, marine tourism and urban development.[73]

Tourism

editTourism is a mainstay of the economy. The following are tourist sites that are within the walled city of Cartagena:

- Colonial architecture with Andalusian style roots. Many of the houses in Cartagena have balconies with tropical flowers.[74]

- Convent, cloister and chapel of Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de la Popa, located at the top of Mount Popa

- Cathedral of Santa Catalina de Alejandría

- Church and cloister of San Pedro Claver

- Convent and church of Santo Domingo

- Palace of Inquisition

- Teatro Heredia[75]

- Cartagena Gold Museum[76]

- Las Bóvedas

- Clock Tower

- Fortresses in Cartagena de Indias: Of the twenty fortresses comprising the walls in the district of Getsemaní, today 16 are still standing, preserved in good condition. In 1586, it was commissioned to the most famous military engineer of the Crown of Spain in that time, the Italian Battista Antonelli, the fortification of the city. The works of the project finally ended in the 17th century. Cartagena became an impregnable bastion, which successfully resisted the attacks of Baron Pontis to 1697. In the 18th century, new additions gave the fortified complex its current amplitude by engineer Antonio de Arévalo. The initial fortification system includes only the urban recint, the bastion port of San Matías at the entrance to the passage of Bocagrande, and the Tower of San Felipe del Boquerón that controlled the Bay of las Ánimas. Gradually, all passages were dominated by fortresses: fortress of San Luis, fortress of San José and fortress of San Fernando in Bocachica, fortress of San Rafaél and fortress of Santa Bárbara in Pochachica (the passage at southwest), fortress of Santa Cruz, fortress of San Juan de Manzanillo and fortress of San Sebasi de Pastellilo around the interior of Bahía, castle of San Felipe de Barajas, in the rock that dominates the city from the east and access to protected the Isthmus del Cerebro. The fortifications of San Felipe de Barajas in Cartagena, protected the city during numerous sieges, giving its character and reputation unassailable. These are described as a masterpiece of Spanish military engineering in the Americas.

The city has a budding hotel industry with small boutique hotels being primarily concentrated in the Walled City and larger hotels in the beach front neighborhood of Bocagrande. The area of Getsemaní just outside the wall is also a popular place for small hotels and hostels.[77]

The following are tourist sites that are outside the city of Cartagena:

- Las Islas del Rosario: These islands are one of Colombia's most important national parks. Most of the islands can be reached in an hour or less from the city docks.

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editAs the commercial and touristic hub of the country, the city has many transportation facilities, particularly in the seaport, air, and fluvial areas.[citation needed]

In 2003,[78] the city started building Transcaribe, a mass transit system. In 2015 the system began operating in the city. Taxis are also a prevalent form of public transportation and there is a bus terminal connecting the city to other cities along the coast and in Colombia.[79]

Cartagena has problems of traffic congestion.[80]

Roads

editThe city is linked to the northern part of the Caribbean Region through roads 90 and 90A, more commonly called Central Caribbean Road. This road passes through Barranquilla, Santa Marta and Riohacha ending in Paraguachón, Venezuela and continues with Venezuelan numeration all the way to Caracas. Taxis in the city perimeter do not have fare meters.[81]

The following roads are in the southeast portion of the city:[clarification needed] Road 25: Going through Turbaco and Arjona, and through the Montes de María when a fork divides it continuing to Sincelejo as National 25 and finally ending in Medellín, and to the east to Valledupar as number 80.

Road 25 A: Going also to Sincelejo, but avoiding the mountains, connects with Road 25 in the forementioned city.[clarification needed]

Air

editThe Rafael Núñez International Airport is the busiest airport in Colombia's Caribbean region and the fourth in passenger traffic in the country. The code of the airport is CTG, having flights to almost all airports in Colombia including Bogota's El Dorado International Airport. Excessive operational costs and easier connection travel and better prices had led to the shifting of the Rafael Núñez's international connection passengers away from Bogota to the nearer Tocumen International Airport in Panama and Queen Beatrix International Airport in Aruba. Also, more companies prefer to serve the Colombian market from Cartagena, due to better geographical and atmospheric conditions.[82]

Sea

editCartagena is the most important port of Colombia in the Caribbean.[83]

The open ports of the city are:

- Port Society of Cartagena - Specializing in container management, this port is first of its class in the country, the third busiest port on the Caribbean Sea, and ranked 99th among ports of the world.[84]

- Muelles El Bosque (El Bosque Docks) - specialized in grain storage, expanding to the container market[85]

- Container Terminal of Cartagena - container management

Private ports of the city:

- The port of the Cartagena Oil Refinery (REFICAR S.A.)

- SABMiller brewery port

- Argos cement port

- Dow Chemical raw materials embarkment port

- BASF Colombia raw materials embarkment port

- Du Pont private embarkment port

- Cemex cement port

- Dole packing house

- Colombian Navy steelworks port

Canals

editSince the 17th century the bay has been connected to the Magdalena River by the Dique Canal, built by Governor Pedro Zapata de Mendoza. After Colombian independence, the canal was abandoned. Increasing centralization left the city without resources to maintain it. The last important maintenance work was done in the 1950s during Laureano Gómez's administration. Some improvements were made by local authorities in the 1980s. This was discontinued because of legal objections from the central government that decreed that the "maintenance" of the canal did not fall under the jurisdiction of the local government. From then on, maintenance of the canal has been delayed, though it is still functional.[86]

Cartagenian political leaders have argued that this state of affairs might change with a return to pre-independence funding and tax system. Under such systems the canal would be maintained properly and even expanded, benefiting the national economy.[87]

Waste disposal

editCartagena is one of the few cities in the world with a marine outfall, inaugurated in 2013,[88] whose 4.3-kilometer (2.7 mi)-long underwater section is the third longest in the world.[89]

Education

editColleges and universities

editPrimary and secondary schools

editInternational schools include:

- Corporacion Educativa Colegio Britanico de Cartagena (British)

- Gimnasio Cartagena de Indias (International)

- Colegio Jorge Washington (American)

Libraries

editThe city has many public and private libraries:

- The Universidad de Cartagena José Fernández Madrid Library: Started in 1821 when the university opened as the "University of Magdalena and Isthmus". Serves mainly the students and faculty of this university but anyone can use its services.

- Divided in buildings across the city being assigned to the Faculties it serves accordingly each area. The main building is in C. de la Universidad 64 and the second biggest section is located in Av. Jose Vicente Mogollón 2839.[90]

- The Bartolomé Calvo Library: Founded in 1843 and established in its current place in 1900, it is one of the main libraries on the Caribbean Coast and the largest in the city. Its address is Calle de la Inquisición, 23.

- The History Academy of Cartagena de Indias Library: Opened in 1903, many of its books date from more than a century before from donations of members and benefactors. Its entrance is more restricted due to secure handling procedure reasons as ancient books require, but it can be requested in the academy office in Plaza de Bolivar 112.

- The Technological University of Bolívar Library: Opened in 1985 Although small in general size, its sections on engineering and electronics are immense and its demand is mostly on this area, being located in Camino de Arroyohondo 1829.

- The American Hispanic Culture Library: Opened in 1999, it already existed a smaller version without Spanish funding in the Casa de España since the early 1940s but in 1999 was enlarged to serve Latin America and the Caribbean in the old convent of Santo Domingo. It specializes in Hispanic Culture and History and is a continental epicenter of seminaries on history and restoration of buildings. The restoration of the convent and the enlargement of the library was and still is a personal project of Juan Carlos I of Spain who visits it regularly. It is located in Plaza Santo Domingo 30, but its entrance is in C. Gastelbondo 52.

- Jorge Artel Library: Opened in 1997, serves the area of the southwest districts of the city, it is mostly for children. It is located in Camino del Socorro 222

- Balbino Carreazo Library: Located in Pasacaballos, a suburban neighborhood of the southeastern part of the city, serves mostly the suburbs of Pasacaballos, Ararca, Leticia del Dique and Matunilla. It is located in Plaza de Pasacaballos 321

- District Libraries: Although small, this system goes grassroots to neighborhoods circulating books, generally each district library has around 5000 books.[91]

Culture

editTheaters and concert halls

editThe first carnivals and western theaters that served in New Granada operated on, what is today, Calle del Coliseo. This was an activity patronized by the Viceroy Manuel de Guirior and Antonio Caballero y Góngora, who, like their predecessors, spent most of the time of their mandates ruling in Cartagena.

- Teatro Adolfo Mejía: former Teatro Heredia, opened in 1911, inspired by the Teatro Tacón of Havana, was designed by Jose Enrique Jaspe. After years of abandonment, it was rebuilt in the 1990s and continues to be a cultural center. It is located in Plazuela de La Merced 5.[92]

Sport

editTigres de Cartagena represent the city in the Colombian Professional Baseball League, playing at Estadio Once de Noviembre. Other historical baseball teams that once represented Cartagena include Indios, Águilas, and Torices.

The main football club in the city is Real Cartagena.

In August 2024, Cartagena co-hosted the 2024 U-15 Baseball World Cup with Barranquilla.[93]

Museums and galleries

edit- City Museum Palace of the Inquisition, opened in the 1970s [citation needed]

- Sanctuary and Museum of St. Maria Bernarda Bütler (foundress of the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of Perpetual Help)[94]

World Heritage site

editThe port, the fortresses and the group of monuments of Cartagena were selected in 1984 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as significant to the heritage of the world, having the most extensive fortifications in South America. They are significant, too, for being located in a bay that is part of the Caribbean Sea. A system of zones divides the city into three neighborhoods: San Sebastian and Santa Catalina with the cathedral and many palaces where the wealthy lived and the main government buildings functioned; San Diego or Santo Toribio, where merchants and the middle class lived; and Getsemani, the suburban popular quarters.[95]

Festivities

edit- January: The "Cartagena International Music Festival" (Cartagena Festival Internacional de Música), Classical music event that has become one of the most important festivals in the country. It is done in the Walled City for 10 days, during which are held classes, conferences and counted with the presence of national and international artists.

- "Fiesta Taurina del Caribe" (Caribbean Bullfight festival) (ultimately canceled, for maintenance of the scenario)

- "SummerLand Festival": Electronic music festival most important of the country

- February: "Fiestas de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria" (Feasts of Our Lady of Candelaria),

- "Festival del Frito"

- March: "International Film Festival of Cartagena" (Festival Internacional de Cine de Cartagena)

- " Miss Colombia"

- "Feria Nautica"

- April: "Festival del Dulce" (Festival of the Sweets)

- June–July: "Festival de Verano" (Summer Festival)

- "Sail Cartagena"

- November: "Fiestas del 11 de noviembre" (Feasts of 11 November or of the Independence)

- December: "Jazz Festival under the Moon" (Festival de Jazz bajo la Luna)

- "Cartagena Rock"

Media appearances

editFilm

edit- Burn! (1969), with Marlon Brando, was filmed in Cartagena.

- In the movie Romancing the Stone (1984), romance novelist Joan Wilder (Kathleen Turner) travels to Cartagena to deliver a treasure map, in an effort to ransom her kidnapped sister. The Cartagena scenes were actually filmed in Mexico. In the movie, Michael Douglas' character refers to it as Cartage(ny)a. This has largely been adopted by tourists and is an irritant to the locals. The "N" in Cartagena is hard.

- The film The Mission (1986), with Robert De Niro, was filmed in Cartagena and Brazil[96]

- The film Love in the Time of Cholera (2007) was filmed in Cartagena.

- Scenes of Gemini Man (2019), with Will Smith, were filmed in Cartagena.

- Scenes of the (2023) film Sound of Freedom

Television

edit- In the Family Guy episode "Barely Legal", the mayor, thinking the events of Romancing the Stone (see above) are real, sends all the city's police officers to Cartagena[citation needed]

- Cartagena figured prominently in the "Smuggler's Blues" (1985) episode of Miami Vice, featuring guest star Glenn Frey and his song "Smuggler's Blues"[97]

- Cartagena is featured as the backdrop for the NCIS episodes "Agent Afloat" and "The Missionary Position".[98][99]

- The 30th installment of MTV's reality competition series, titled The Challenge XXX: Dirty 30, was filmed in Cartagena.[100]

- In the Orphan Black episode "To Right the Wrongs of Many", Delphine and Cosima are in Cartagena, where Delphine is giving the cure to the Leda clone found there.[101]

- The Colombian Netflix show Siempre Bruja (Always a Witch) is set in Cartagena.[102]

- In The Amazing Race 28, the second and third legs were set in Cartagena and required teams to visit various locations throughout the city.[103][104]

- In Season 10 of The Real Housewives of New York City, the annual cast vacation takes place in Cartagena.[105]

Literature

edit- A fictionalized version of the 1697 raid on Cartagena is chronicled in the novel Captain Blood (1922).[106]

- Gabriel García Márquez's novel Love in the Time of Cholera is set in an unnamed city based on Cartagena. García Márquez has also said that Cartagena influenced the setting of The Autumn of the Patriarch.[107] His novel Of Love and Other Demons takes place in Cartagena in the 1600s.[108]

- The first chapter of Brian Jacques' novel The Angel's Command (2003) takes place in Cartagena in 1628.[citation needed]

- The poem "Románc" (1983) by Sándor Kányádi talks about the beauty of Cartagena.[citation needed]

- The second story in Nam Le's award-winning book of short fiction, The Boat (2008) is called "Cartagena" and set in Colombia. Cartagena in the story is more an idea than a place.[citation needed]

- A portion of the 2014 novel The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell (author) is set in the city.[109]

- A 2015 novel by Claudia Amengual is named Cartagena.[110]

- The poem "A mi ciudad nativa" is in honor of Cartagena[111]

Video games

edit- The city is the scene of two levels in the video game Uncharted 3: Drake's Deception.[112]

Music

editChampeta is a musical genre whose main variants are rooted in Cartagena and Barranquilla.[113]

- On the album Corazón Profundo, Carlos Vives honored the city of Cartagena, calling it "The Fantastic City" (in Spanish: La fantástica).[114]

- The 2016 song "Otra Vez" by Zion & Lennox mentions Cartagena.

- The song "1741 (The Battle of Cartagena)" by Alestorm off their 2014 Album Sunset on the Golden Age is about the 1741 siege of Cartagena.

Notable people

edit- Joe Arroyo, salsa music composer and singer[115]

- Valeria Ayos, Miss Universe Colombia 2021

- Alvaro Barrios, conceptual artist[116]

- Bartolomé Calvo, politician, journalist, Governor of Panama (1856–58), President of the Granadine Confederation in 1861

- Bernardo Caraballo, boxer

- Alfonso Múnera Cavadía, diplomat and historian[117]

- Antonio Cervantes, boxer

- Saint Peter Claver SJ, Jesuit priest, pastor and missionary to the slaves brought to Cartagena ("Slave of the slaves forever"), human rights advocate. Beatified 1850 by Pope Pius IX, canonized 1888 by Pope Leo XIII. 1985, the Colombian Congress declared 9 September, his feast day, as Human Rights national day in his honor.[118]

- William Dau, former Mayor of Cartagena

- Germán Espinosa, writer, author of "La Tejedora de Coronas" (The weaver of crowns) and 40 other works[119]

- José María García de Toledo, politician, early "juntismo" movement member, later independentist; President of the Supreme Junta of Cartagena (1810–11)[120]

- Laura González, Miss Colombia 2017

- Enrique Grau, painter, born in Panama but raised in the city where most of his work was done and inspired[121]

- Dilson Herrera, professional baseball player[122]

- Zharick León, actress[123]

- Nereo Lopez, documentary photographer[124]

- Manuel Medrano, singer

- Andrea Nocetti, Miss Colombia 2001

- Rafael Núñez, politician, journalist, diplomat, writer, lawyer and judge. Dominant political figure in Colombia in the 19th century, and the first to did so by civil means: In 1848 just after another civil war entered in local politics. Then became MP for Cartagena in the Colombian Congress, also was Governor of Bolívar (1854), then briefly Minister of War in 1855–57. President of the Sovereign State of Bolivar twice, (1876–77) (1879–80) was finally elected 4 times President of Colombia. During this time the country stabilized and the economy grew after decades of civil war and established the foundations for civil-led government with the Colombian Constitution of 1886 that lasted 105 years. Also wrote the country's national anthem.

- Laura Olascuaga, Miss Universe Colombia 2020

- Alfonso Pérez, boxer

- Carlos Pizarro Leongómez, guerrilla fighter for the 19th of April Movement

- Sabas Pretelt de la Vega, politician and ambassador, Minister of Interior (2003–06)[125]

- Frey Ramos, footballer

- Ramses Ramos, actor

- Hugo Soto, footballer

- Julio Teherán, professional baseball player[126]

- Gio Urshela, professional baseball player

- Rodrigo Valdez, boxer

- Kevin Flórez, singer

- Karoll Márquez, singer

- Teresa Román Vélez, writer

- Orlando Cabrera, baseball player

- Jeymmy Vargas, beauty queen and model

- Vanessa Rosales Altamar, author

- Laura De León Céspedes, actress

- Angie Cepeda, actress

- Lorna Cepeda, actress

- Eduardo Lemaitre, historian

- Salomón Bustamante Sanmiguel, TV host

- Patricia Teherán Romero, singer

- Rafael Vergara Navarro, lawyer

See also

edit- San Basilio de Palenque, according to UNESCO, the first free African town in the Americas, located 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Cartagena de Indias

- Rosario Islands, an archipelago located 100 kilometres (62 miles) from Cartagena with a large coral reef

- List of tallest buildings in Cartagena

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cartagena in Colombia

- Manuel Rodríguez Torices

- Cartagena Manifesto

- United Provinces of New Granada

- Gran Colombia

- War of the Supremes

- 1829–51 cholera pandemic, in which 4000 Cartageneros died in 1849[17]: 72

Notes

edit- ^ Peter Claver was a Spanish-born man who traveled to Cartagena in 1610. On 19 March 1616 he was ordained as a Jesuit priest. Peter cared for the African slaves for thirty-eight years, defending the life and the dignity of the slaves. After four years of sickness, Peter died in 1654. Two services were held for him: the official funeral, and a separate memorial attended by his African friends. In 1888, the Roman Catholic Church canonized Peter. He is now known as the patron saint of African-Americans, slaves and the Republic of Colombia.[52][53]

References

edit- ^ Batista, Lia Miranda (1 January 2020). "William Dau Chamatt se posesionó como nuevo alcalde de Cartagena" [William Dau Chamatt Takes Office As the New Mayor of Cartagena]. El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Proyecciones de Población 2018–2020, total municipal por área (estimate)". DANE. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ Proyecciones de Población 2018–2020, total municipal por área. DANE (Report) (in Spanish). 2020. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ "TelluBase—Colombia Fact Sheet (Tellusant Public Service Series)" (PDF). Tellusant. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Lance R. Grahn, "Cartagena" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, p 581. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Citypopulation.de

- ^ "Big on Charm: Colonial Cartagena". Travel. 17 November 2015.

- ^ Grahn, "Cartagena" p. 582.

- ^ Arqueología y Patrimonio https://revistas.icanh.gov.co/index.php/ap/article/download/2623/2020.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango". Lablaa.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Colombia Pais Maravilloso". Pwp.supercabletv.net.co. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Universidad del Norte". Uninorte.edu.co. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango". Lablaa.org. 4 June 2005. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "X Cátedra de Historia Ernesto Restrepo Tirado – El Caribe en la Nación Colombiana" Guerra, Langbaek et al. Ed. Aguilar, Bogotá, 2007. ISBN 958-8250-31-5.

- ^ Allaire, Louis (1997). "The Caribs of the Lesser Antilles". In Samuel M. Wilson, The Indigenous People of the Caribbean, pp. 180–85. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1531-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Lemaitre, Eduardo (1994). A Brief History of Cartagena. Medellin: Compania Litografica Nacional S.A. p. 13. ISBN 978-958-638-092-8.

- ^ a b c Parry, John; Keith, Robert (1984). New Iberian World: A Documentary History of the Discovery and Settlement of Latin America to the Early 17th Century, Vol. II. New York: Times Books. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-8129-1070-4.

- ^ Lemaitre, Eduardo; Historia Extensa de Cartagena de Indias, Ed. Aguilar 1976. Edited before the ISBN system was enforced in Colombia, no reedition.

- ^ Floyd, Troy (1973). The Columbus Dynasty in the Caribbean, 1492–1526. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 49, 89, 95, 135.

- ^ "Diego de Nicuesa". Bruceruiz.net. 22 April 2002. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Related Articles. "Rodrigo de Bastidas (Colombian explorer) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Rodrigo de Bastidas". Bruceruiz.net. 3 July 2002. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Lemaitre, Eduardo; Historia Extensa de Cartagena de Indias, Ed. Aguilar 1976.

- ^ Corrales, Manuel Ezequiel; Documentos para la historia de la Provincia de Cartagena, Tomo II, Imp. M. Rivas, Cartagena de Indias, 1883.

- ^ "The Atlantic World: America and the Netherlands (Cartagena)". Library of Congress.

- ^ "Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango". Lablaa.org. 1 June 2005. Archived from the original on 19 October 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Segovia, Rodolfo (2009). The Fortifications of Cartagena de Indias. Bogota: el Ancora Editores. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-958-36-0134-7.

- ^ De Castellanos, Juan; Historia de Cartagena, Bogotá: Biblioteca de Cultura Popular de Colombia, 1942.[page needed]

- ^ "Historia general y natural de las Indias, islas y tierra-firme del mar océano. Primera parte – Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes". Cervantesvirtual.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Sir John Hawkins". Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ a b Meisel Roca, Adolfo (April 2002). "Crecimiento a Traves de los Subsidios – Cartagena de Indias y El Situado, 1751-1810" [Growth Through Subsidies – Cartagena de Indias and Surrounding Area, 1751-1810] (PDF). Cuadernos de Historia Económica y Empresarial [Journal of History, Economics, and Business] (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ a b "The Caribbean Raid 1585-1586: Sir Francis Drake: A Pictorial Biography by Hans P. Kraus (Rare Book and Special Collections Reading Room)". Library of Congress. 31 August 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Génesis y desarrollo de la esclavitud en Colombia siglos XVI y XVII (in Spanish). Universidad del Valle. 2005. ISBN 978-958-670-338-3.

- ^ Alvaro Gärtner (2005). Los místeres de las minas: crónica de la colonia europea más grande de Colombia en el siglo XIX, surgida alrededor de las minas de Marmato, Supía y Riosucio. Universidad de Caldas. ISBN 978-958-8231-42-6.

- ^ "La esclavitud negra en la América española" (in Spanish). gabrielbernat.es. 2003.

- ^ "Castillo San Felipe de Barajas". Incartagenaguide.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ "Pirate Encyclopedia: Port of Cartagena". Ageofpirates.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Álvarez, Jesús (23 October 2014). "El hombre que causó la mayor derrota sufrida jamás por la Armada inglesa" ["The man who caused the greatest defeat ever suffered by the English Navy]. ABC de Sevilla (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Bassi, Ernesto (1 February 2020). "No Limits to Their Sway: Cartagena's Privateers and the Masterless Caribbean in the Age of Revolutions". Hispanic American Historical Review (Book review). 100 (1): 161–163. doi:10.1215/00182168-7993342. S2CID 212810434.

- ^ This is used today by restoration architects in Cartagena's city center. The original census is preserved in the Museum of History of the city while a copy rests in the Archivo de Indias in Seville

- ^ FERNANDO CARREÑO ARRÁZOLA (25 June 2017). "Retratos de la nostalgia". El Universal (Cartagena).

- ^ "Street in Cartagena 1850-1930". New York Public Library.

- ^ "Biography of Pedro Romero – Black, Working Class Hero of Cartagena's Independence". Cartagena Explorer. 25 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Consequences of Cartagena's Independence". Cartagena Explorer. 19 November 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "History of Cartagena – A Comprehensive Guide to the History of Cartagena, Colombia". Cartagena Explorer. 11 July 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Cartagena | Colombia". Encyclopedia Britannica. 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Country Files (GNS)". National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ Rangel-Buitrago, Nelson; Anfuso, Giorgio (2015). Risk assessment of storms in coastal zones. Springer.

- ^ Restrepo, Juan D.; Escobar, Rogger; Tosic, Marko (February 2018). "Fluvial fluxes from the Magdalena River into Cartagena Bay, Caribbean Colombia: Trends, future scenarios, and connections with upstream human impacts". Geomorphology. 302: 92–105. Bibcode:2018Geomo.302...92R. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.11.007. hdl:10784/26918.

- ^ "La Torre del Reloj Testigo Silencioso de un pasado" [The Clock Tower: Silent Witness to the Past]. Traviata Nuestra (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ Proceso de beatificación y canonización de San Pedro Claver. Edición de 1696. Traducción del latín y del italiano, y notas de Anna María Splendiani y Tulio Aristizábal S. J. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Universidad Católica del Táchira. 2002.

- ^ Valtierra, Ángel. 1964. San Pedro Claver, el santo que liberó una raza.

- ^ Moon, Freda (10 September 2014). "36 Hours in Cartagena, Colombia". The New York Times.

- ^ "AD's Guide to Cartagena, Colombia". Architectural Digest. 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Cartagena attractions: Las Bovedas". Viator. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Clímaco Calderón, Edward E. Britton. "Colombia 1893". Yale University Library Digital Collections.

- ^ Saladino, Emily (23 August 2013). "A renaissance beyond Cartagena's historic walls". Travel. BBC. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ "Medellin vs. Cartagena vs. Bogota: Which is the Best Colombian City for Your Next Vacation?". Tripelle. 23 March 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ Orejarena-Rondón, Andrés F.; Sayol, Juan M.; Marcos, Marta; Otero, Luis; Restrepo, Juan C.; Hernández-Carrasco, Ismael; Orfila, Alejandro (1 October 2019). "Coastal Impacts Driven by Sea-Level Rise in Cartagena de Indias". Frontiers in Marine Science. 6. doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00614. hdl:10261/202816.

- ^ "Promedios Climatológicos 1991–2020" (in Spanish). Instituto de Hidrologia Meteorologia y Estudios Ambientales. Archived from the original on 6 June 2024. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ "Promedios Climatológicos 1981–2010" (in Spanish). Instituto de Hidrologia Meteorologia y Estudios Ambientales. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Promedios Climatológicos 1971–2000" (in Spanish). Instituto de Hidrologia Meteorologia y Estudios Ambientales. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Tiempo y Clima" (in Spanish). Instituto de Hidrologia Meteorologia y Estudios Ambientales. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Cartagena, Colombia – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ "UV Index in Cartagena, Colombia". Nomadseason. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ "PERFIL CARTAGENA-DANE" (PDF).

- ^ "¿En qué certamen internacional participará Sofia Osio Luna, la Señorita Colombia 2022?". Diario AS (in Spanish). 13 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ "What to Expect During the Cartagena November Festivities (2019 Update)". Cartagena Explorer. 13 October 2019.

- ^ "Zonas Francas Permanentes en Colombia". Invierta en Colombia (in European Spanish). Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Zonas Francas Colombia" (PDF). Asociacion Zonas Francas. 2017.

- ^ "Parque Central – Free Trade Zone – Zona Franca". Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Garcia Martinez, Eduardo (10 August 1993). "Aprueban Zona Franca Turística en Isla De Barú" [Tourist Free Zone Approved in Isla De Barú]. El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "Big on Charm: Colonial Cartagena". Travel. 17 November 2015. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Teatro Heredia". Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ "Museo del Oro de Cartagena". Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Where to Stay in Cartagena? – Insider's Guide (with recommendations, 2019 update)". Cartagena Explorer. 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Transcaribe". Transcaribe. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Getting Around Cartagena – A Comprehensive Guide to Transportation in Cartagena, Colombia". Cartagena Explorer. 28 June 2019.

- ^ Gonzalez-Urango, Hannia; Pira, Michela Le; Inturri, Giuseppe; Ignaccolo, Matteo; García-Melón, Mónica (2020). "Designing walkable streets in congested touristic cities: the case of Cartagena de Indias, Colombia". Transportation Research Procedia. 45: 309–316. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2020.03.021. hdl:20.500.12442/5225.

- ^ "Getting Around Cartagena - A Comprehensive Guide to Transportation in Cartagena, Colombia". Cartagena Explorer. 8 August 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "En Marzo Entregan Obras en el Aeropuerto". El Universal. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ Stein, Alfredo; Moser, Caroline (April 2014). "Asset planning for climate change adaptation: lessons from Cartagena, Colombia". Environment and Urbanization. 26 (1): 166–183. doi:10.1177/0956247813519046.

- ^ "Contecar – Sociedad Portuaria Regional Cartagena". Puertocartagena.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Terminal Marítimo Muelles El Bosque S.A". Elbosque.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Lemaitre, Eduardo; Historia Extensa de Cartagena de Indias, Ed. Aguilar 1976

- ^ "El Porvenir", Year CXVII, Issue 29.399, p. 4, column 2. Cartagena de Indias, 1999.

- ^ "Se inaugura el Emisario Submarino" (in Spanish). El Universal. 20 March 2013.

- ^ "Emisario Submarino: ¡por fin!" (in Spanish). El Universal. 20 March 2013.

- ^ "Universidad de Cartagena – Biblioteca". Unicartagena.edu.co. Archived from the original on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Patrimonio Cultural – Instituto de Cultura de Cartagena Colombia". Ipcc.gov.co. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Teatro Heredia" [Heredia Theatre]. Cartagena Travel (in Spanish). 2002. Archived from the original on 23 April 2002. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "Schedule revealed for WBSC U-15 Baseball World Cup 2024; Hosts Colombia take on Italy on opening day". WBSC. World Baseball Softball Confederation (WBSC). Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ "Un museo que mueve el espíritu". eluniversal.com.co. 6 February 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena". Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ The Mission – IMDb

- ^ Smuggler's Blues, Miami Vice – IMDb

- ^ Agent Afloat, NCIS – IMDb

- ^ The Missionary Position, NCIS – IMDb

- ^ "'The Challenge': Welcome to 'The Real World: Redemption House'". EW.com.

- ^ ""Orphan Black", Season 5, Episode 10, Series Finale, "To Right the Wrongs of Many" - the Snarking Dead TV Recaps". Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Siempre Bruja – IMDb

- ^ Davis, Joslyn; Robinson, Erin (20 February 2016). "Amazing Race Insider: Erin Robinson and Joslyn Davis Share Leg 2 Secrets". TVLine. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Walker, Jodi. "The Amazing Race recap: Bros Being Jocks". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Wigging Out". IMDb.

- ^ "Captain Blood, by Rafael Sabatini". Retrieved 24 February 2019 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Williams, Raymond Leslie (March 1989). "The Visual Arts, the Poetization of Space and Writing: An Interview with Gabriel García Márquez". PMLA. 104 (2): 131–40. doi:10.2307/462499. JSTOR 462499. S2CID 163626383.

- ^ "Del amor y otros demonios". www.litencyc.com. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ Kavenna, Joanna (30 August 2014). "The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell, review: 'painstakingly kind to the reader'". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Cartagena". goodreads.com. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Análisis de 'A mi ciudad nativa' de Luis Carlos López". Dialnet (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Naughty Dog (1 November 2011). Uncharted 3: Drake's Deception (PlayStation 3). Sony Computer Entertainment. Level/area: Chapter 2 – Greatness from Small Beginnings and Chapter 3 – Second Story Work.

- ^ Martínez, Luis. "La champeta". Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "LA FANTÁSTICA - CARLOS VIVES (Homenaje)HD". YouTube.

- ^ "La plaza de Majagual, famosa por el Joe Arroyo". La Chachara (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "Barrios, Álvaro | banrepcultural.org". www.banrepcultural.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "Alfonso Múnera, nuevo secretario de la Asociación de Estados del Caribe". www.eluniversal.com.co (in European Spanish). 11 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Sladky, Joseph (8 September 2014). "St. Peter Claver: Slave of the Slaves Forever". Crisis Magazine - A Voice for the Faithful Catholic Laity. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ McDonnell, Patrick J. (29 October 2007). "Cartagena, Colombia revels in love, sans cholera". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "García Toledo, José María | banrepcultural.org". www.banrepcultural.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ "Enrique Grau, 83; His Art Depicted Indians, Afro-Colombians". Los Angeles Times. 3 April 2004. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "Dilson Herrera Stats, Fantasy & News". Cincinnati Reds (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ "Zharick León reapareció en redes con sensuales fotos". El Universal (in Spanish). 18 August 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Fallece el fotógrafo Nereo López". revistaarcadia.com. 25 August 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ Tiempo, Casa Editorial El. "Sabas Pretelt de la Vega: Perfil y columnas de Sabas Pretelt de la Vega". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ VIP, WordPress com. "Braves sign Julio Teheran to six-year extension | Jeff Schultz blog". Retrieved 21 January 2017.

Further reading

editColonial history

edit- Álvarez Alonso, Fermina. La Inquisición en Cartagena de Indias durante el siglo XVII. Madrid: Fundación Universitaria Española, 1999.

- Bossa Herrazo, Donaldo. Nomenclatur cartagenero. 1981.

- Böttcher, Nikolaus. "Negreros portugueses y la Inquisición de Cartagena de Indias, siglo XVII." Memoria 9 (2003): 38–55.

- Dorta, Enrique Marco. Cartagena de Indias: Puerto y plaza fuerte. 1960.

- Escobar Quevedo, Ricardo. "Los Criptojudíos de Cartagena de Indias: Un eslabón en la diáspora conversa (1635–1649)." Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 29 (2002): 45–71.

- Fals-Borda, Orlando. Historia doble de la costa. 4 vols. 1979–1986.

- Goodsell, James Nelson. "Cartagena de Indias: Entrepôt for a New World, 1533–1597." PhD dissertation, Harvard University 1966.

- Grahn, Lance R. "Cartagena and Its Hinterland in the Eighteenth Century" in Atlantic Port Cities: Economy, Culture, and Society in the Atlantic World, 1650–1850. Franklin W. Knight and Peggy K. Liss, eds. 1991, pp. 168–95.

- Grahn, Lance R. "Cartagena" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, pp. 581–82. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Greenow, Linda. Family, Household, and Home: A Microgeographic Analysis of Cartagena (New Granada) in 1777. 1976.

- Greenow, Linda. "Urban form in Spanish American colonial cities: Cartagena de Indias, New Granada, in 1777." Department of Geography Suny-New Paltz, NY. Middle States Geographer (2007).

- Lemaitre, Eduardo. Historia general de Cartagena. 4 vols. Bogota: Banco de la República, 1983.

- McKnight, Kathryn Joy. "Confronted Rituals: Spanish Colonial and Angolan" Maroon" Executions in Cartagena de Indias (1634)." Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 5.3 (2004).

- Medina, José Toríbio. Historia del Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisicón de Cartagena de Indias. Santiago: Imprenta Elzeviriana, 1899.

- Meisel, Adolfo. "Subsidy-Led Growth In A Fortified Port: Cartagena De Indias And The Situado, 1751–1810." Borradores de Economía 167 (2000).

- Molino García, María Paulina. "La sede vacante en Cartagena de Indias, 1534–1700." Anuario de Estudios Americanos 32 (1975): 1–23.

- Newson, Linda A., and Susie Minchin. "Slave mortality and African origins: a view from Cartagena, Colombia, in the early seventeenth century." Slavery & Abolition 25.3 (2004): 18–43.

- Olsen, Margaret M. Slavery and Salvation in Colonial Cartagena de Indias. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004.

- Pacheco, Juan Manuel. "Sublevación portuguesa en Cartagena." Boletín de historia y antigüedades 42 (1955): 557–60.

- Rey Fajardo, José del. Los jesuitas en Cartagena de Indias, 1604–1767. Bogota: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 2004.

- Rocha, Carlos Guilherme. "A disputa por poder em Cartagena das Índias: o embate entre o governador Francisco de Murga e o Tribunal do Santo Ofício (1629–1636)." (2013).

- Ruiz Rivera, Julián B. "Cartagena de Indias: ¿Un cabildo cosmopolita en una ciudad pluriétnica?" In El municipio indiano: Relaciones interétnicas, económicas y sociales. Homenaje a Luis Navarro García, edited by Manuela Cristina García Bernal and Sandra Olivero Guidobono, 407–24. Seville: Universidad de Sevilla, 2009.

- –––. "Gobierno, comercio y sociedad en Cartagena de Indias en el siglo XVII." In Cartagena de Indias en el siglo XVII, edited by Haroldo Calvo Stevenson and Adolfo Meisel Roca, 353–76. Cartagena: Banco de la República, 2007.

- –––. "Los regimientos de Cartagena de Indias." In La venta de cargos y el ejercicio del poder en Cartagena de Indias, edited by Julián B. Ruiz Rivera y Ángel Sanz Tapia, 199–221. León: Universidad de León, 2007.

- –––. Cartagena de Indias y su provincia: Una mirada a los siglos XVII y XVIII. Bogota: El Áncora Editores, 2005.

- –––. "Municipio, puerto y provincia (1600–1650)." In Julián B. Ruiz Rivera, Cartagena de Indias y su provincia: Una mirada a los siglos XVII y XVIII, 203–24. Bogota: El Áncora Editores, 2005.

- –––. "Vanquésel, casa de préstamos en Cartagena de Indias." In Estudios sobre América: siglos XVI–XX, edited by Antonio Gutiérrez Escudero and María Luisa Laviana Cuetos, 673–89. Seville: Asociación Española de Americanistas, 2005.

- –––. "Una banca en el mercado de negros de Cartagena de Indias." Temas americanistas 17 (2004): 3–23.

- –––. "Los portugueses y la trata negrera en Cartagena de Indias." Temas americanistas 15 (2002): 19–41.

- Salazar, Ricardo Raul. "Running Chanzas: Slave-State Interactions in Cartagena de Indias, 1580 to 1713." Diss. Harvard University, 2014.

- Sánchez Bohórquez, José Enrique. "La Inquisición en América durante los siglos XVI–XVII: Los dominicos y el Tribunal de Cartagena de Indias." In Praedicatores inquisitores, vol. 2, La Orden Dominicana y la Inquisición en el mundo ibérico e hispanoamericano, 753–808. Rome: Istituto Storico Domenicano, 2006.

- Solano Alonso, Jairo. Salud, cultura y sociedad en Cartagena de Indias, siglos XVI y XVII In De la Roma Medieval a la Cartagena Colonial: El Santo Oficio de la Inquisición. Vol. I of Cincuenta Años de Inquisición en el Tribunal de Cartagena deIndias, 1610–1660, edited by Anna María Splendiani, et al. Bogotá: Centro EditorialJaveriano, 1997.. Barranquilla: Universidad del Atlántico, 1998.

- Splendiani, Anna María, et al. eds. De la Roma Medieval a la Cartagena Colonial: El Santo Oficio de la Inquisición. Vol. I of Cincuenta Años de Inquisición en el Tribunal de Cartagena de Indias, 1610–1660, Bogotá: Centro Editorial Javeriano, 1997.

- Tejado Fernández, Manuel. "El tribunal de Cartagena de Indias: La primera mitad del siglo XVII(1621–1650)." In Historia de la Inquisición en España y América, 3 vols., edited by Joaquín Pérez Villanueva and Bartolomé Escandell Bonet, I.1141–45. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Inquisitoriales, 1984.

- –––. "La ampliación del dispositivo: Fundación del Tribunal de Cartagena de Indias." In Historia de la Inquisición en España y América, 3 vols., edited by Joaquín Pérez Villanueva and Bartolomé Escandell Bonet, I.984–95. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Inquisitoriales, 1984.

- –––. Aspectos de la vida social en Cartagena de Indias durante el seiscientos. Seville: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1954.

- –––. "Un foco de judaísmo en Cartagena de Indias durante el seiscientos." Bulletin Hispanique 52 (1950): 55–72.

- Vidal Ortega, Antonino. Cartagena de Indias y la región histórica del Caribe, 1580–1640. Seville: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 2002.

- –––. "Portugueses negreros en Cartagena, 1580–1640", in IV Seminario internacional de estudios del Caribe: Memorias, 135–54. Bogota: Fondo de Publicaciones de la Universidad del Atlántico, 1999.